Pulsar

Pulsars are highly magnetized, rotating neutron stars that emit a beam of electromagnetic radiation. The radiation can only be observed when the beam of emission is pointing towards the Earth. This is called the lighthouse effect and gives rise to the pulsed nature that gives pulsars their name. Because neutron stars are very dense objects, the rotation period and thus the interval between observed pulses is very regular. For some pulsars, the regularity of pulsation is as precise as an atomic clock.[1] The observed periods of their pulses range from 1.4 milliseconds to 8.5 seconds.[2] A few pulsars are known to have planets orbiting them, such as PSR B1257+12. Werner Becker of the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics said in 2006, "The theory of how pulsars emit their radiation is still in its infancy, even after nearly forty years of work."[3]

Contents |

Formation

The events leading to the formation of a pulsar begin when the core of a massive star is compressed during a supernova, which collapses into a neutron star. The neutron star retains most of its angular momentum, and since it has only a tiny fraction of its progenitor's radius (and therefore its moment of inertia is sharply reduced), it is formed with very high rotation speed. A beam of radiation is emitted along the magnetic axis of the pulsar, which spins along with the rotation of the neutron star. The magnetic axis of the pulsar determines the direction of the electromagnetic beam, with the magnetic axis not necessarily being the same as its rotational axis. This misalignment causes the beam to be seen once for every rotation of the neutron star, which leads to the "pulsed" nature of its appearance. The beam originates from the rotational energy of the neutron star, which generates an electrical field from the movement of the very strong magnetic field, resulting in the acceleration of protons and electrons on the star surface and the creation of an electromagnetic beam emanating from the poles of the magnetic field.[4][5] This rotation slows down over time as electromagnetic power is emitted. When a pulsar's spin period slows down sufficiently, the radio pulsar mechanism is believed to turn off (the so-called "death line"). This turn-off seems to take place after about 10-100 million years, which means of all the neutron stars in the 13.6 billion year age of the universe, around 99% no longer pulsate.[6] To date, the slowest observed pulsar has a period of 8 seconds.

Discovery

The first pulsar was observed on November 28, 1967 by Jocelyn Bell Burnell and Antony Hewish.[7][8][9] Initially baffled as to the seemingly unnatural regularity of its emissions, they dubbed their discovery LGM-1, for "little green men" (a name for intelligent beings of extraterrestrial origin). While the hypothesis that pulsars were beacons from extraterrestrial civilizations was never taken very seriously, some discussed the far-reaching implications if it turned out to be true.[10] Their pulsar was later dubbed CP 1919, and is now known by a number of designators including PSR 1919+21, PSR B1919+21 and PSR J1921+2153. Although CP 1919 emits in radio wavelengths, pulsars have, subsequently, been found to emit in visible light, X-ray, and/or gamma ray wavelengths.[11]

The word "pulsar" is a contraction of "pulsating star", and first appeared in print in 1968:

An entirely novel kind of star came to light on Aug. 6 last year and was referred to, by astronomers, as LGM (Little Green Men). Now it is thought to be a novel type between a white dwarf and a neutron [sic]. The name Pulsar is likely to be given to it. Dr. A. Hewish told me yesterday: "… I am sure that today every radio telescope is looking at the Pulsars."[12]

The suggestion that pulsars were rotating neutron stars was put forth independently by Thomas Gold and Franco Pacini in 1968, and was soon proven beyond reasonable doubt by the discovery of a pulsar with a very short (33-millisecond) pulse period in the Crab nebula.

In 1974, Antony Hewish became the first astronomer to be awarded the Nobel Prize in physics. Considerable controversy is associated with the fact that Professor Hewish was awarded the prize while Bell, who made the initial discovery while she was his Ph.D student, was not.

Subsequent history

In 1974, Joseph Hooton Taylor, Jr. and Russell Hulse discovered the first time pulsar in a binary system, PSR B1913+16. This pulsar orbits another neutron star with an orbital period of just eight hours. Einstein's theory of general relativity predicts that this system should emit strong gravitational radiation, causing the orbit to continually contract as it loses orbital energy. Observations of the pulsar soon confirmed this prediction, providing the first ever evidence of the existence of gravitational waves. As of 2004, observations of this pulsar continue to agree with general relativity. In 1993, the Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Taylor and Hulse for the discovery of this pulsar.[13]

In 1982, Don Backer led a group which discovered PSR B1937+21, a pulsar with a rotation period of just 1.6 milliseconds.[14] Observations soon revealed that its magnetic field was much weaker than ordinary pulsars, while further discoveries cemented the idea that a new class of object, the "millisecond pulsars" (MSPs) had been found. MSPs are believed to be the end product of X-ray binaries. Owing to their extraordinarily rapid and stable rotation, MSPs can be used by astronomers as clocks rivaling the stability of the best atomic clocks on Earth. Factors affecting the arrival time of pulses at the Earth by more than a few hundred nanoseconds can be easily detected and used to make precise measurements. Physical parameters accessible through pulsar timing include the 3D position of the pulsar, its proper motion, the electron content of the interstellar medium along the propagation path, the orbital parameters of any binary companion, the pulsar rotation period and its evolution with time. (These are computed from the raw timing data by Tempo, a computer program specialized for this task.) After these factors have been taken into account, deviations between the observed arrival times and predictions made using these parameters can be found and attributed to one of three possibilities: intrinsic variations in the spin period of the pulsar, errors in the realization of Terrestrial Time against which arrival times were measured, or the presence of background gravitational waves. Scientists are currently attempting to resolve these possibilities by comparing the deviations seen amongst several different pulsars, forming what is known as a Pulsar Timing Array. With luck, these efforts may lead to a time scale a factor of ten or better than currently available, and the first ever direct detection of gravitational waves. In June 2006, the astronomer John Middleditch and his team at LANL announced the first prediction of pulsar glitches with observational data from the Rossi X-ray Timing Explorer. They used observations of the pulsar PSR J0537-6910.

In 1992, Aleksander Wolszczan discovered the first extrasolar planets around PSR B1257+12. This discovery presented important evidence concerning the widespread existence of planets outside the solar system, although it is very unlikely that any life form could survive in the environment of intense radiation near a pulsar.

Categories

Three distinct classes of pulsars are currently known to astronomers, according to the source of the power of the electromagnetic radiation:

- Rotation-powered pulsars, where the loss of rotational energy of the star provides the power.

- Accretion-powered pulsars (accounting for most but not all X-ray pulsars), where the gravitational potential energy of accreted matter is the power source (producing X-rays that are observable from the Earth).

- Magnetars, where the decay of an extremely strong magnetic field provides the electromagnetic power.

The Fermi Space Telescope has uncovered a subclass of rotationally-powered pulsars that emit only gamma rays.[15] There have been only about twelve gamma-ray pulsars identified out of about 1800 known pulsars.[16][17]

Although all three classes of objects are neutron stars, their observable behavior and the underlying physics are quite different. There are, however, connections. For example, X-ray pulsars are probably old rotationally-powered pulsars that have already lost most of their power, and have only become visible again after their binary companions had expanded and began transferring matter on to the neutron star. The process of accretion can in turn transfer enough angular momentum to the neutron star to "recycle" it as a rotation-powered millisecond pulsar. As this matter lands on the neutron star, it is thought to "bury" the magnetic field of the neutron star (although the details are unclear), leaving millisecond pulsars with magnetic fields 1000-10,000 times weaker than average pulsars. This low magnetic field is less effective at slowing the pulsar's rotation, so millisecond pulsars live for billions of years, making them the oldest known pulsars. Millisecond pulsars are seen in globular clusters, which stopped forming neutron stars billions of years ago.[6]

Of interest to the study of the state of the matter in a neutron stars are the glitches observed in the rotation velocity of the neutron star. This velocity is decreasing slowly but steadily, except by sudden variations. One model put forward to explain these glitches is that they are the result of "starquakes" that adjust the crust of the neutron star. Models where the glitch is due to a decoupling of the possibly superconducting interior of the star have also been advanced. In both cases, the star's moment of inertia changes, but its angular momentum doesn't, resulting in a change in rotation rate.

Naming

Initially pulsars were named with letters of the discovering observatory followed by their right ascension (e.g. CP 1919). As more pulsars were discovered, the letter code became unwieldy and so the convention was then superseded by the letters PSR (Pulsating Source of Radio) followed by the pulsar's right ascension and degrees of declination (e.g. PSR 0531+21) and sometimes declination to a tenth of a degree (e.g. PSR 1913+167). Pulsars that are very close together sometimes have letters appended (e.g. PSR 0021-72C and PSR 0021-72D).

The modern convention is to prefix the older numbers with a B (e.g. PSR B1919+21) with the B meaning the coordinates are for the 1950.0 epoch. All new pulsars have a J indicating 2000.0 coordinates and also have declination including minutes (e.g. PSR J1921+2153). Pulsars that were discovered before 1993 tend to retain their B names rather than use their J names (e.g. PSR J1921+2153 is more commonly known as PSR B1919+21). Recently discovered pulsars only have a J name (e.g. PSR J0437-4715). All pulsars have a J name that provides more precise coordinates of its location in the sky.[18]

Applications

The study of pulsars has resulted in many applications in physics and astronomy. Striking examples include the confirmation of the existence of gravitational radiation as predicted by general relativity and the first detection of an extrasolar planetary system.

The discovery of pulsars allowed astronomers to study an object never observed before, the neutron star. This kind of object is the only place where the behavior of matter at nuclear density can be observed (though not directly). Also, millisecond pulsars have allowed a test of general relativity in conditions of an intense gravitational field.

Pulsar maps have been included on the two Pioneer Plaques as well as the Voyager Golden Record. They show the position of the Sun, relative to 14 pulsars, which are identified by the unique timing of their electromagnetic pulses, so that our position both in space and in time can be calculated by potential extraterrestrial intelligences.[19][20]

As probes of the interstellar medium

The radiation from pulsars passes through the interstellar medium (ISM) before reaching Earth. Free electrons in the warm (8000 K), ionized component of the ISM and H II regions affect the radiation in two primary ways. The resulting changes to the pulsar's radiation provide an important probe of the ISM itself.[21]

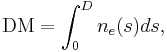

Due to the dispersive nature of the interstellar plasma, lower-frequency radio waves travel through the medium slower than higher-frequency radio waves. The resulting delay in the arrival of pulses at a range of frequencies is directly measurable as the dispersion measure of the pulsar. The dispersion measure is the total column density of free electrons between the observer and the pulsar,

where  is the distance from the pulsar to the observer and

is the distance from the pulsar to the observer and  is the electron density of the ISM. The dispersion measure is used to construct models of the free electron distribution in the Milky Way Galaxy.[22]

is the electron density of the ISM. The dispersion measure is used to construct models of the free electron distribution in the Milky Way Galaxy.[22]

Additionally, turbulence in the interstellar gas causes density inhomogeneities in the ISM which cause scattering of the radio waves from the pulsar. The resulting scintillation of the radio waves—the same effect as the twinkling of a star in visible light due to density variations in the Earth's atmosphere—can be used to reconstruct information about the small scale variations in the ISM.[23] Due to the high velocity (up to several hundred km/s) of many pulsars, a single pulsar scans the ISM rapidly, which results in changing scintillation patterns over timescales of a few minutes.[24]

Significant pulsars

- The first radio pulsar CP 1919 (now known as PSR 1919+21), with a pulse period of 1.337 seconds and a pulse width of 0.04 second, was discovered in 1967.[25] A drawing of this pulsar's radio waves was used as the cover of British post-punk band Joy Division's debut album, Unknown Pleasures.

- The first binary pulsar, PSR 1913+16, whose orbit is decaying at the exact rate predicted due to the emission of gravitational radiation by general relativity

- The first millisecond pulsar, PSR B1937+21

- The brightest millisecond pulsar, PSR J0437-4715

- The first X-ray pulsar, Cen X-3

- The first accreting millisecond X-ray pulsar, SAX J1808.4-3658

- The first pulsar with planets, PSR B1257+12

- The first double pulsar binary system, PSR J0737−3039

- The longest period pulsar, PSR J2144-3933

- The most stable pulsar in period, PSR J0437-4715

- The magnetar SGR 1806-20 produced the largest burst of power in the Galaxy ever experimentally recorded on 27 December 2004[26]

- PSR B1931+24 "... appears as a normal pulsar for about a week and then 'switches off' for about one month before emitting pulses again. [..] this pulsar slows down more rapidly when the pulsar is on than when it is off. [.. the] braking mechanism must be related to the radio emission and the processes creating it and the additional slow-down can be explained by the pulsar wind leaving the pulsar's magnetosphere and carrying away rotational energy.[27]

- PSR J1748-2446ad, at 716 Hz, the pulsar with the highest rotation speed.

- PSR J0108-1431, the closest known pulsar to the Earth. It lies in the direction of the constellation Cetus, at a distance of about 85 parsecs (280 light years). Nevertheless, it was not discovered until 1993 due to its extremely low luminosity. It was discovered by the Danish astronomer Thomas Tauris.[28] in collaboration with a team of Australian and European astronomers using the Parkes 64-meter radio telescope. The pulsar is 1000 times weaker than an average radio pulsar and thus this pulsar may represent the tip of an iceberg of a population of more than half a million such dim pulsars crowding our Milky Way.[29][30]

- PSR J1903+0327, a ~2.15 ms pulsar discovered to be in a highly eccentric binary star system with a sun-like star.[31]

- A pulsar in the CTA 1 supernova remnant (4U 0000+72, in Cassiopeia) was found by the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope to emit pulsations only in gamma ray radiation, the first recorded of its kind.[15]

See also

- Neutron star

- Anomalous X-ray pulsar

- Magnetar

- Millisecond pulsar

- Radio pulsar

- Rotating radio transient

- Soft gamma repeater

- X-ray pulsar

- Pulsar wind

- Pulsar wind nebula

- Pulsar planets

- Black Hole

- Optical pulsar

Notes

- ↑ Matsakis, D. N.; Taylor, J. H.; Eubanks, T. M. (1997). "A Statistic for Describing Pulsar and Clock Stabilities". Astronomy and Astrophysics 326: 924–928. http://aa.springer.de/papers/7326003/2300924.pdf. Retrieved 2010-04-03.

- ↑ "A Radio Pulsar with an 8.5-Second Period that Challenges Emission Models". Nature 400: 848–849. 1999. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v400/n6747/abs/400848a0.html. Retrieved 2010-04-03.

- ↑ Press Release: Old Pulsars Still Have New Tricks to Teach Us. European Space Agency, 26 July 2006.

- ↑ "Pulsar Beacon Animation". http://www3.amherst.edu/~gsgreenstein/progs/animations/pulsar_beacon/. Retrieved 2010-04-03.

- ↑ "Pulsars". http://imagine.gsfc.nasa.gov/docs/science/know_l2/pulsars.html. Retrieved 2010-04-03.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 http://www.cv.nrao.edu/course/astr534/Pulsars.html

- ↑ Pranab Ghosh, Rotation and accretion powered pulsars. World Scientific, 2007, p.2.

- ↑ M. S. Longair, Our evolving universe. CUP Archive, 1996, p.72.

- ↑ M. S. Longair, High energy astrophysics, Volume 2. Cambridge University Press, 1994, p.99.

- ↑ Sturrock, Peter A. The UFO Enigma: A New Review of the Physical Evidence. Warner Books, 1999 (page 154).

- ↑ Courtland, Rachel. "Pulsar Detected by Gamma Waves Only." New Scientist, 17 October 2008.

- ↑ Daily Telegraph, 21/3, 5 March 1968.

- ↑ "Nobel Prize in Physics 1993". http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1993/. Retrieved 2010-01-07.

- ↑ D. Backer et al. (1982). "A millisecond pulsar". Nature 300: 315–318. doi:10.1038/300615a0. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v300/n5893/abs/300615a0.html.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Atkinson, Nancy. "Fermi Telescope Makes First Big Discovery: Gamma Ray Pulsar." Universe Today, 17 October 2008.

- ↑ NASA'S Fermi Telescope Unveils a Dozen New Pulsars http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/GLAST/news/dozen_pulsars.html

- ↑ Cosmos Online - New Kind of pulsar discovered (http://www.cosmosmagazine.com/news/2260/new-kind-pulsar-discovered)

- ↑ Lyne, Andrew G.; Graham-Smith, Francis. Pulsar Astronomy. Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- ↑ http://astro.ysc.go.jp/pioneer10-plaque.txt

- ↑ http://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/spacecraft/goldenrec1.html

- ↑ Ferriere, K. "The Interstellar Environment of Our Galaxy." Reviews of Modern Physics, Volume 73, Issue 4, 2001 (pages 1031–1066).

- ↑ Taylor, J. H.; Cordes, J. M. "Pulsar Distances and the Galactic Distribution of Free Electrons." Astrophysical Journal, Volume 411, 1993 (page 674).

- ↑ Rickett, Barney J. "Radio Propagation Through the Turbulent Interstellar Plasma." Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Volume 28, 1990 (page 561).

- ↑ Rickett, Barney J.; Lyne, Andrew G.; Gupta, Yashwant. "Interstellar Fringes from Pulsar B0834+06." Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Volume 287, 1997 (page 739).

- ↑ Hewish, A. et al. "Observation of a Rapidly Pulsating Radio Source." Nature, Volume 217, 1968 (pages 709-713).

- ↑ "Galactic Magnetar Throws Giant Flare." Astronomy Picture of the Day, 21 February 2005.

- ↑ "Part-Time Pulsar Yields New Insight Into Inner Workings of Cosmic Clocks." Particle Physics and Astronomy Research Council, 3 March 2006.

- ↑ Tauris, T. M. et al. "Discovery of PSR J0108-1431: The Closest Known Neutron Star?" Astrophysical Journal, Volume 428, 1994 (page L53).

- ↑ Crowsell, K. "Science: Dim Pulsars May Crowd Our Galaxy." New Scientist, Number 1930, 18 June 2008. (page 16).

- ↑ "Closest Pulsar?" Sky & Telescope, October 1994 (page 14).

- ↑ Champion, David J. et al. "An Eccentric Binary Millisecond Pulsar in the Galactic Plane." Science, 6 June 2008 Volume 320, Number 5881 (pages 1309-1312).

References and further reading

- Lorimer, Duncan R. "Binary and Millisecond Pulsars at the New Millennium." Living Reviews, Relativity 4, 2001.

- Lorimer, Duncan R.; Kramer, M. "Handbook of Pulsar Astronomy." Cambridge Observing Handbooks for Research Astronomers, 2004.

- Stairs, Ingrid H. "Testing General Relativity with Pulsar Timing." Living Reviews, Relativity 6, 2003.

- Sturrock, Peter A. The UFO Enigma: A New Review of the Physical Evidence. Warner Books, 1999 (ISBN 0-446-52565-0).

External links

- "Pinning Down a Pulsar’s Age". Science News.

- "Astronomical whirling dervishes hide their age well". Astronomy Now.

- Animation of a Pulsar. Einstein.com, 17 January 2008.

- "The Discovery of Pulsars." BBC, 23 December 2002.

- "A Pulsar Discovery: First Optical Pulsar." Moments of Discovery, American Institute of Physics, 2007 (Includes audio and teachers guides).

- Discovery of Pulsars: Interview with Jocelyn Bell-Burnell. Jodcast, June 2007 (Low Quality Version).

- Audio: Cain/Gay - Astronomy Cast. Pulsars - Nov 2009

- Listing for PULS CP 1919 (The First Pulsar), Simbad Database

- Australia National Telescope Facility: Pulsar Catalogue

- Johnston, William Robert. "List of Pulsars in Binary Systems." Johnston Archive, 22 March 2005.

- Staff Writers. "Scientists Can Predict Pulsar Starquakes." Space Daily, 7 June 2006.

- Staff Writers. "XMM-Newton Makes New Discoveries About Old Pulsars." Space Daily, 27 July 2006.

- Than, Ker. "Hot New Idea: How Dead Stars Go Cold." Space.com, 27 July 2006.

- "New Kind of Pulsar Discovered"[1]. Cosmos Online.

- Artist's Rendition of Pulsar. Digital Blasphemy.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||