Pteranodon

| Pteranodon Fossil range: Late Cretaceous, 88–80.5 Ma |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Mounted male and female P. sternbergi skeletons at the Royal Ontario Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Pterosauria |

| Suborder: | Pterodactyloidea |

| Family: | Pteranodontidae |

| Genus: | Pteranodon Marsh, 1876 |

| Species | |

|

|

| Synonyms | |

|

|

Pteranodon (pronounced /tɨˈrænədɒn/; from Greek πτερ- "wing" and αν-οδων "toothless"), from the Late Cretaceous of North America (Kansas, Alabama, Nebraska, Wyoming, and South Dakota), was one of the largest pterosaur genera, with a wingspan of up to 9 metres (30 ft). Pteranodon is known from more fossil specimens than any other pterosaur, with about 1,200 specimens known to science, many of them well preserved with complete skulls and articulated skeletons, and was an important part of the animal community present in the Western Interior Seaway.[1]

Pteranodon was a reptile, but not a dinosaur. All dinosaurs are diapsid reptiles with an upright stance, and by definition Dinosauria consists of the groups Saurischia and Ornithischia, which excludes Pterosauria. While the advanced pterodactyloid pterosaurs (like Pteranodon) had a semi-upright stance, this evolved independently of the upright stance in dinosaurs, and pterosaurs lacked the distinctive adaptations in the hip associated with the dinosaurian posture. However, dinosaurs and pterosaurs may have been closely related, and most paleontologists place them together in the group Ornithodira, or "bird necks".

Contents |

Description

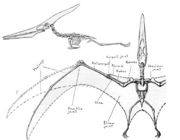

Pteranodon was among the largest pterosaurs, with the wingspan of most adults ranging between three and six meters (9–20 ft). While most specimens are found crushed, enough fossils exist to put together a detailed description of the animal.

Unlike earlier pterosaurs such as Rhamphorhynchus and Pterodactylus, Pteranodon had toothless beaks, similar to those of modern birds. Pteranodon beaks were made of solid, bony margins that projected from the base of the jaws. The beaks were long, slender, and ended in sharp points. The upper jaw was longer than the lower jaw. The upper jaw was curved upward; while this has normally been attributed only to the upward-curving beak, one specimen (UALVP 24238) has a curvature corresponding with the beak actually widening towards the tip. While the tip of the beak is not known in this specimen, the level of curvature suggests it would have been extremely long. This led Bennett (1994) to suggest that the upward curve was not entirely due to a curved beak, but rather indicated an Anhanguera-like sloping crest on the front of the beak (premaxilla). However, further specimens would be necessary to determine the actual structure of the beak in P. sternbergi. Some specimens of both P. sternbergi and P. longiceps do preserve the beak tips, and lack any premaxillary crests.[2]

The most distinctive characteristic of Pteranodon is its primary cranial crest. These crests consisted of skull bones (frontals) projecting upward and backward from the skull. The size and shape of these crests varied due to a number of factors, including age, sex, and species. Male Pteranodon sternbergi, the older species, had a more vertical crest with a broad forward projection, while their descendants, Pteranodon longiceps, evolved a narrower, more backwards-projecting crest.[1] Females of both species were smaller, and bore small, rounded crests.[2] See the Paleobiology section below for more on crests and their function.

Other distinguishing characteristics that set Pteranodon apart from other pterosaurs include narrow neural spines on the vertebrae, plate-like bony ligaments strengthening the vertebrae above the hip, and a short tail in which the last few vertebrae are fused into a rod.[2]

There are two species of Pteranodon currently recognized as valid: Pteranodon longiceps (the type species) and Pteranodon sternbergi. The species differ only in the shape of the crest in adult males (described above), and possibly in the angle of certain skull bones.[2]

Pteranodon fossils are known from the Niobrara and Pierre Formations of the central United States. Pteranodon existed as a group for over four million years during the late Coniacian - early Campanian stages of the Cretaceous period.[2] It is present in most layers of the Niobrarra Formation except for the upper two; in 2003, Kenneth Carpenter surveyed the distribution and dating of fossils in this formation, demonstrating that Pteranodon sternbergi existed there from 88-85 million years ago, while P. longiceps existed between 86-84.5 million years ago. A possible third species is known from the Sharon springs member of the Pierre Shale Formation in Kansas, Wyoming and South Dakota, dating to between 81.5 and 80.5 million years ago.[3]

History of discovery

Pteranodon was the first pterosaur found outside of Europe. Its fossils were first found by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1870, in the Late Cretaceous Smoky Hill Chalk of western Kansas. These chalk beds were deposited at the bottom of what was once the Western Interior Seaway, a large shallow sea over what is now midsection of the North American continent. These first specimens, YPM 1160 and YPM 1161, consisted of partial wing bones, as well as a tooth from the prehistoric fish Xiphactinus, which Marsh mistakenly believed to belong to his new pterosaur (all known pterosaurs up to that point had teeth). In 1871, Marsh named the find Pterodactlyus Oweni, assigning it to the well-known (but much smaller) European genus Pterodactylus. Marsh also collected more wing bones of the large pterosaur in 1871. Realizing that the name Pterodactylus oweni had in 1864 already been used for a specimen of the European Pterodactylus, Marsh re-named his North American pterosaur Pterodactylus occidentalis, or "Western wing finger," in his 1872 description of the new specimen. He also named two additional species, based on size differences: Pterodactylus ingens (the largest specimen so far), and Pterodactlyus velox (the smallest).[2]

Meanwhile, Marsh's rival Edward Drinker Cope had also unearthed several specimens of the large North American pterosaur. Based on these specimens, Cope named two new species, Ornithochirus umbrosus and Ornithochirus harpyia, in an attempt to assign them to the large European genus Ornithocheirus. However, as he misspelled the name (forgetting the 'e'), he accidentally created an entirely new genus.[2] Cope's paper naming his ''Ornithochirus species was published in 1872, just five days after Marsh's paper. This resulted in a dispute, fought in the published literature, over whose names had priority in what were obviously the same species.[2] Cope conceded in 1875 that Marsh's names did have priority over his, but maintained that Pterodactylus umbrosus was a distinct species (but not genus) from any that Marsh had named previously.[4] Re-evaluation by later scientists has supported Marsh's case, and found that Cope's assertion that P. umbrosus was a larger, distinct species were wrong.[2]

While the first Pteranodon wing bones were collected by Marsh and Cope in the early 1870s, the first Pteranodon skull was found on May 2, 1876, along the Smoky Hill River in Wallace County (now Logan County), Kansas, USA, by Samuel Wendell Williston, a fossil collector working for Marsh.[1] A second, smaller skull soon followed. These skulls showed that the North American pterosaur was different than any European species, in that they lacked teeth. Marsh recognized that this major difference, describing the specimens as "distinguished from all previously known genera of the order Pterosauria by the entire absence of teeth." Marsh recognized that this warranted a new genus, and he coined the name Pteranodon ("wing without tooth") in 1876. Marsh also reclassified all the previously named North American species from Pterodactylus to Pteranodon, with the larger skull, YPM 1117, referred to the new species Pteranodon longiceps.[5] He also named an additional species, Pteranodon gracilis, based on a wing bone that he mistook for a pelvic bone. He realized his mistake, and re-classified this specimen in a separate genus, which he named Nyctosaurus.[6]

Paleobiology

Diet

The diet of Pteranodon is known to have included fish; fossilized fish bones have been found in the stomach area of one Pteranodon, and a fossilized fish bolus has been found between the rami of another Pteranodon, specimen AMNH 5098.

Flight

The wing shape of Pteranodon suggests that it would have flown rather like a modern-day albatross. This is a suggestion based on the fact that the Pteranodon had a high aspect ratio (wingspan to chord length) similar to that of the albatross — 9:1 for Pteranodon, compared to 8:1 for an albatross. Albatrosses spend long stretches of time at sea fishing, and utilize a flight pattern called "dynamic soaring" which exploits the vertical gradient of wind speed near the ocean surface to travel long distances without flapping, and without the aid of thermals (which do not occur over the open ocean the same way they do over land).[7] However, most scientists do agree that Pteranodon could flap their wings and fly with power. These two flight styles would not have been mutually exclusive in Pteranodon, or in pterosaurs in general.

Crest

Pteranodon was notable for its skull crest, though the function of the crest has been a subject of debate. However, most explanations have focused on the blade-like, backward pointed crest of male P. longiceps, and ignored the wide range of variation across age and gender. The fact that the crests vary so much rules out most practical functions other than for use in mating displays.

George Francis Eaton, in 1910, proposed two possible functions for the crest: as an aerodynamic counterbalance, and as a muscle attachment point. He suggested that the crest might have anchored large, long jaw muscles, but admitted that this function alone could not explain the large size of some crests.[8] Bennett (1992) agreed with Eaton's own assessment that the crest was too large and variable to have been a muscle attachment site.[9] Eaton had suggested that a secondary function of the crest might have been as a counterbalance against the long beak, reducing the need for heavy neck muscles to control the orientation of the head.[8] Wind tunnel tests showed that the crest did function as an effective counterbalance to a degree, but Bennett noted that the hypothesis again focuses only on the long crests of male P. longiceps, not on the larger crests of P. sternbergi and very small crests of females. Bennett found that the crests of females had no counterbalancing effect, and that the crests of male P. sternbergi would, by themselves, have a negative effect on the balance of the head. Side to side movement of the crests would actually have required more, not less, neck musculature to control.[9]

In 1943, Dominik von Kripp suggested that the crest may have served as a rudder, an idea embraced by several later researchers.[9][10] One researcher, Ross S. Stein, even suggested that the crest may have supported a membrane of skin connecting the backward-pointing crest to the neck and back, increasing its surface area and effectiveness as a rudder.[11] The rudder hypothesis again does not take into account females or P. sternbergi, which had an upward-pointing, not backward-pointing crest. Bennett also found that even in its capacity as a rudder, the crest would not provide nearly as much directional force as simply maneuvering the wings. The suggestion that the crest was an air brake, and that the animals would turn their heads to the side in order to slow down, suffers from a similar problem.[12] Additionally, the rudder and air brake hypotheses do not explain why such large variation exists in crest size even among adults.[9]

Alexander Kellner suggested that the large crests of the pterosaur Tapejara, as well as other species, might be used for heat exchange, allowing these pterosaurs to absorb or shed heat and regulate body temperature, which would also account for the correlation between crest size and body size. However, there is no evidence of extra blood vessels in the crest for this purpose, and the large, membranous wings filled with blood vessels would have served that purpose much more effectively.[9]

With the above hypotheses ruled out, the best supported hypothesis for crest function seems to be as a sexual display. This is consistent with the size variation seen in fossil specimens, where juveniles and females have small crests and males large, elaborate, variable crests.[9]

Sexual variation

Adult Pteranodon specimens can be divided into two distinct size classes, small and large, with the large size class being about one and a half times larger than the small, and the small being twice as common as the large. Both size classes lived along side each other, and while researchers had previously suggested that they represent different species, Christopher Bennett showed that the differences between them are consistent with the idea that they represent males and females, and that Pteranodon species were sexually dimorphic. Skulls from the larger size class preserve large, upwards and backward pointing crests, while the crests of the smaller size class are small and triangular. Some larger skulls also show evidence of a second crest that extended long and low along toward the tip of the beak, which is not seen in smaller specimens.[9]

The sex of the different size classes was determined not from the skulls, but from the pelvic bones. Contrary to what may be expected, the smaller size class had disproportionately large and wide-set pelvic bones. Bennett interpreted this as indicating a more spacious birth canal, through which eggs would pass. He concluded that the small size class with small, triangular crests represent females, and the larger, large-crested specimens are male.[9]

Note that the overall size and crest size also corresponds to age. Immature specimens are known from both females and males, and immature males often have small crests similar to adult females. Therefore, it seems that the large crests only developed in males when they reached their large, adult size, making the sex of immature specimens difficult to establish from partial remains.[13]

The fact that females appear to have outnumbered males two to one suggests that, like modern animals with size-related sexual dimorphism such as sea lions and other pinnipeds, Pteranodon were polygynous, with a few males presiding over, and competing for, large numbers of females. Like modern pinnipeds, Pteranodon may have fought to establish territory on rocky, offshore rookeries, with the largest, and largest-crested, males gaining the most territory and having more success mating with females. The crests of male Pteranodon would not have been used in competition, but rather as "visual dominance-rank symbols", with display rituals taking the place of physical competition with other males. It is also likely that male Pteranodon played little to no part in rearing the young; such a behavior is not found in the males of modern polygynous animals.[9]

Locomotion

The terrestrial locomotion of Pteranodon, especially whether it was bipedal or quadrupedal, has historically been the subject of debate. Today, most pterosaur researchers agree that pterosaurs were quadrupedal, thanks largely to the discovery of several pterosaur trackways. The possibility of swimming has been discussed briefly in two papers (Bennett 2001 and Bramwell & Whitfield 1974), and has been studied in detail at Michigan State University through the use of quantitative morphometrics and an extant phylogenetic bracket (a morphologically comparative technique invented by Larry Witmer).[12][14]

Paleoecology

The Smoky Hill Chalk, where most Pteranodon fossils are found, is the upper part of the Niobrara Formation and is famous for the fossils collected there since 1869. When Pteranodon was alive, the area was covered in a large inland sea, known as the Western Interior Seaway, over which Pteranodon would have soared and hunted fish and small invertebrates. Pteranodon longiceps would have shared the sky with the giant-crested pterosaur Nyctosaurus. However, compared to Pteranodon, which would have been a very common species, Nyctosaurus was rare, making up only 3% of pterosaur fossils from the formation. Also less common was the early toothed bird, Ichthyornis.

It is likely that, as in other polygynous animals (in which males compete over harems of females), Pteranodon lived primarily on offshore rookeries, where they could nest away from land-based predators and feed far from shore; most Pteranodon fossils are found in locations at the time hundreds of kilometres from the coastline.[9]

Below the surface, the sea was populated primarily by invertebrates such as ammonites and squid. Vertebrate life, apart from basal fish, included sea turtles like Toxochelys, the plesiosaur Styxosaurus, and the flightless diving bird Parahesperornis. Mosasaurs were the most common marine reptiles, with genera including Clidastes and Tylosaurus.[1] At least some of these marine reptiles are known to have fed on Pteranodon. Barnum Brown, in 1904, reported plesiosaur stomach contents containing "pterodactyl" bones, most likely from Pteranodon.[15]

Fossils from terrestrial dinosaurs have also been found in the Niobrara Chalk, suggesting that animals which died on shore must have been washed out to sea (one specimen of a hadrosaur appears to have been scavenged by a shark).[16]

Classification

Species

A number of species of Pteranodon have been named since the 1870s, though most are now considered to be junior synonyms of two or three valid species. The best-supported is the type species, P. longiceps, based on the well-preserved specimen including the first-known skull found by S.W. Williston. This individual had a wingspan of 7 m (23 ft).[17] Other valid species include the possibly larger P. sternbergi, with a wingspan originally estimated at 9 m (30 ft).[17] P. occidentalis, P. velox, P. umbrosus, P. harpyia and P. comptus are considered to be nomina dubia by Bennett (1994) and others. All are probably synonymous with the more well-known species.

Pteranodon sternbergi is the only known species of Pteranodon with an upright-crest. The lower jaw of P. sternbergi was 1.25 meters (4 ft) long.[18] It was collected by George F. Sternberg in 1952 and described by John Christian Harksen in 1966, from the lower portion of the Niobrara Formation. It was older than P. longiceps and is considered by Bennett to be the direct ancestor of the later species.[2]

List of species and synonyms

Because the key distinguishing characteristic Marsh noted for Pteranodon was its lack of teeth, any toothless pterosaur jaw fragment, wherever it was found in the world, tended to be attributed to Pteranodon during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This resulted in a plethora of species and a great deal of confusion. The name became a wastebasket taxon, rather like the dinosaur Megalosaurus, to label any pterosaur remains that could not be distinguished other than by the absence of teeth. Species (often dubious ones now known to be based on sexual variation or juvenile characters) have been reclassified a number of times, and several sub-genera have in the seventies been erected by Halsey Wilkinson Miller to hold them in various combinations, further confusing the taxonomy (subgenera include Longicepia, Occidentalia, and Geosternbergia). Notable authors who have discussed the various aspects of Pteranodon include Bennett, Padian, Unwin, Kellner, and Wellnhofer. Two species, P. orogensis and P. orientalis, are not actually pteranodontids and have been renamed Bennettazhia oregonensis and Bogolubovia orientalis respectively.

Status of names listed below follow a survey by Bennett, 1994 unless otherwise noted.[2]

| Name | Author | Year | Status | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pterodactylus occidentalis | Marsh | 1872 | Reclassified as Pteranodon occidentalis | Reclassified from Pterodactylus oweni Marsh 1871 (preoccupied by Seeley 1864) |

| Pterodactylus ingens | Marsh | 1872 | Reclassified as Pteranodon ingens | |

| Pterodactylus velox | Marsh | 1872 | Nomen dubium | Reclassified as Pteranodon velox |

| Ornithochirus umbrosus | Cope | 1872 | Nomen dubium | |

| Ornithochirus harpyia | Cope | 1872 | Nomen dubium | |

| Pterodactylus umbrosus | (Cope) Cope | (1872) 1874 | Reclassification of Ornithochirus umbrosus | |

| Pteranodon longiceps | Marsh | 1876 | Valid | Type species |

| Pteranodon ingens | (Marsh) Williston | (1872) 1876 | Nomen dubium | Reclassified from Pterodactylus ingens |

| Pteranodon occidentalis | Marsh | (1872) 1876 | Nomen dubium | Reclassified from Pterodactylus occidentalis |

| Pteranodon velox | Marsh | (1872) 1876 | Nomen dubium | Reclassified from Pterodactylus velox, based on a juvenile specimen |

| Pteranodon gracilis | Marsh | 1876 | Reclassified as Nyctosaurus gracilis | |

| Pteranodon comptus | Marsh | 1876 | Nomen dubium | |

| Pteranodon nanus | Marsh | 1876 | Reclassified as Nyctosaurus nanus | |

| Ornithocheirus umbrosus | (Cope) Newton | (1872) 1888 | Reclassified as Pteranodon umbrosus | Spelling correction of Ornithochirus umbrosus |

| Ornithocheirus harpyia | (Cope) Newton | (1872) 1888 | Reclassified as Pteranodon harpyia | Spelling correction of Ornithochirus harpyia |

| Pteranodon umbrosus | (Cope) Williston | (1872) 1892 | Nomen dubium | Reclassification of Ornithochirus umbrosus |

| Ornithostoma ingens | (Marsh) Williston | (1872) 1893 | Synonym of Pteranodon ingens | Reclassified from Pteranodon ingens |

| Ornithostoma umbrosum | (Cope) Williston | (1872) 1897 | Synonym of Pteranodon umbrosus | Reclassified from Pteranodon umbrosus |

| Pteranodon oregonensis | Gilmore | 1928 | Reclassified as Bennettazhia oregonensis | |

| Pteranodon sternbergi | Harksen | 1966 | Valid | |

| Pteranodon marshi | Miller | 1972 | Synonym of Pteranodon longiceps | |

| Pteranodon bonneri | Miller | 1972 | Reclassified as Nyctosaurus bonneri | |

| Pteranodon walkeri | Miller | 1972 | Synonym of Pteranodon longiceps | |

| Pteranodon (Occidentalia) eatoni | (Miller) Miller | (1972) 1972 | Synonym of Pteranodon sternbergi | |

| Pteranodon eatoni | (Miller) Miller | (1972) 1972 | Synonym of Pteranodon sternbergi | Reclassified from Pteranodon (Occidentalia) eatoni |

| Pteranodon (Longicepia) longicps [sic] | (Marsh) Miller | (1872) 1972 | Synonym of Pteranodon longiceps | Reclassified from Pteranodon longiceps |

| Pteranodon (Longicepia) marshi | (Miller) Miller | (1972) 1972 | Synonym of Pteranodon longiceps | Reclassified from Pteranodon marshi |

| Pteranodon (Sternbergia) sternbergi | (Harksen) Miller | (1966) 1972 | Reclassified as Pteranodon (Geosternbergia) sternbergi | Reclassified from Pteranodon sternbergi |

| Pteranodon (Sternbergia) walkeri | (Miller) Miller | (1972) 1972 | Reclassified as Pteranodon (Geosternbergia) walkeri | Reclassified from Pteranodon walkeri |

| Pteranodon (Pteranodon) marshi | (Miller) Miller | (1972) 1973 | Synonym of Pteranodon longiceps | Reclassified from Pteranodon marshi |

| Pteranodon (Occidentalia) occidentalis | (Marsh) Olshevsky | (1872) 1978 | Synonym of Pteranodon occidentalis | Reclassified from Pteranodon occidentalis |

| Pteranodon (Longicepia) ingens | (Marsh) Olshevsky | (1872) 1978 | Synonym of Pteranodon ingens | Reclassified from Pteranodon ingens |

| Pteranodon (Pteranodon) ingens | (Marsh) Olshevsky | (1872) 1978 | Synonym of Pteranodon ingens | Reclassified from Pteranodon ingens |

| Pteranodon (Geosternbergia) walkeri | (Miller) Miller | (1972) 1978 | Synonym of Pteranodon longiceps | Reclassified from Pteranodon walkeri |

| Pteranodon (Geosternbergia) sternbergi | (Harksen) Miller | (1966) 1978 | Synonym of Pteranodon sternbergi | Reclassified from Pteranodon (Sternbergia) sternbergi |

| Pteranodon orientalis | (Bogolubov) Nesov & Yarkov | (1914) 1989 | Reclassified as Bogolubovia orientalis | Reclassified from Ornithostoma orientalis |

| Geosternbergia walkeri | (Miller) Olshevsky | (1872) 1991 | Synonym of Pteranodon sternbergi | Reclassified from Pteranodon (Sternbergia) walkeri |

| Geosternbergia sternbergi | (Harksen) Olshevsky | (1966) 1991 | Synonym of Pteranodon sternbergi | Reclassified from Pteranodon (Geosternbergia) sternbergi |

In popular culture

Pteranodon is one of the most widely recognized of any pterosaur, having appeared in countless media, such as film, television, literature, video games, etc. For example, Pteranodon played a role in the 2001 Joe Johnston science fiction film Jurassic Park III. For the film, the size of the Pteranodon was increased, and they were depicted as capable of lifting a human in their talons. In reality, the feet were small and incapable of grasping.

See also

- Pterosaur size

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Bennett, S.C. (2000). "Inferring stratigraphic position of fossil vertebrates from the Niobrara Chalk of western Kansas." Current Research in Earth Sciences: Kansas Geological Survey Bulletin, 244(Part 1): 26 pp.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 Bennett, S.C. (1994). "Taxonomy and systematics of the Late Cretaceous pterosaur Pteranodon (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloida)." Occasional Papers of the Natural History Museum, University of Kansas, 169: 1-70.

- ↑ Carpenter, K. (2003). "Vertebrate Biostratigraphy of the Smoky Hill Chalk (Niobrara Formation) and the Sharon Springs Member (Pierre Shale)." High-Resolution Approaches in Stratigraphic Paleontology, 21: 421-437. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9053-0

- ↑ Cope, E.D. (1875). "The Vertebrata of the Cretaceous formations of the West." Report, U. S. Geological Survey of the Territories (Hayden), 2: 302 pp., 57 pls.

- ↑ Marsh, O.C. (1876a). "Notice of a new sub-order of Pterosauria." American Journal of Science, Series 3, 11(65): 507-509.

- ↑ Marsh, O.C., (1876b). "Principal characters of American pterodactyls." American Journal of Science, Series 3, 12(72): 479-480.

- ↑ Padian, K. (1983). "A functional analysis of flying and walking in pterosaurs." Paleobiology, 9(3): 218-239.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Eaton, G.F. (1910). "Osteology of Pteranodon." Memoirs of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2:1-38, pls. i-xxxi.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 9.9 Bennett, S.C. (1992). "Sexual dimorphism of Pteranodon and other pterosaurs, with comments on cranial crests." Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 12(4): 422-434.

- ↑ von Kripp, D. (1943). "Ein Lebensbild von Pteranodon ingens auf flugtechnischer Grundlage." Nova Acta Leopoldina, N.F., 12(83): 16-32 [in German].

- ↑ Stein, R.S. (1975). "Dynamic analysis of Pteranodon ingens: a reptilian adaptation to flight." Journal of Paleontology, 49: 534-548.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Bramwell, C.D. and Whitfield, G.R. (1974). "Biomechanics of Pteranodon." Philosophical Transactions Royal Society B, 267'.

- ↑ Bennett, S.C. (2001). "The osteology and functional morphology of the Late Cretaceous pterosaur Pteranodon. General description of osteology." Palaeontographica, Abteilung A, 260: 1-112.

- ↑ Smith, A.C. (2007). "Pteranodont claw morphology and its implications for aquatic locomotion." Master's Thesis, Michigan State University.

- ↑ Brown, B. (1904). "Stomach stones and the food of plesiosaurs." Science, 20(501): 184-185.

- ↑ Everhart, M.J. and Ewell, K. (2006). {Shark-bitten dinosaur (Hadrosauridae) vertebrae from the Niobrara Chalk (Upper Coniacian) of western Kansas.) Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions, 109(1-2): 27-35.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Wellnhofer, Peter (1996) [1991]. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Pterosaurs. New York: Barnes and Noble Books. pp. 139. ISBN 0-7607-0154-7.

- ↑ Zimmerman, H., Preiss, B., and Sovak, J. (2001). Beyond the Dinosaurs!: sky dragons, sea monsters, mega-mammals, and other prehistoric beasts, Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-689-84113-2.

Further reading

- Anonymous. 1872. On two new Ornithosaurians from Kansas. American Journal of Science, Series 3, 3(17):374-375. (Probably by O. C. Marsh)

- Bennett, S. C. 1987. New evidence on the tail of the pterosaur Pteranodon (Archosauria: Pterosauria). pp. 18–23 In Currie, P. J. and E. H. Koster (eds.), Fourth Symposium on Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems, Short Papers. Occasional Papers of the Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology, #3.

- Bennett, S. C. 2000. New information on the skeletons of Nyctosaurus. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 20(Supplement to Number 3): 29A. (Abstract)

- Bennett, S. C. 2001.The osteology and functional morphology of the Late Cretaceous pterosaur Pteranodon. Part II. Functional morphology. Palaeontographica, Abteilung A, 260:113-153.

- Bennett, S. C. 2003. New crested specimens of the Late Cretaceous pterosaur Nyctosaurus. Paläontologische Zeitschrift, 77:61-75.

- Bennett, S. C. 2007. Articulation and function of the pteroid bone of pterosaurs. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 27:881-891.

- Betts, C. W. 1871. The Yale College Expedition of 1870. Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, 43(257):663-671. (Issue of October, 1871)

- Bonner, O. W. 1964. An osteological study of Nyctosaurus and Trinacromerum with a description of a new species of Nyctosaurus. Unpub. Masters Thesis, Fort Hays State University, 63 pages.

- Brower, J. C. 1983. The aerodynamics of Pteranodon and Nyctosaurus, two large pterosaurs from the Upper Cretaceous of Kansas. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 3(2):84-124.

- Cope, E. D. 1872. On the geology and paleontology of the Cretaceous strata of Kansas. Annual Report of the U. S. Geological Survey of the Territories 5:318-349 (Report for 1871).

- Cope, E. D. 1872. On two new Ornithosaurians from Kansas. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 12(88):420-422.

- Cope, E. D. 1874. Review of the Vertebrata of the Cretaceous period found west of the Mississippi River. U. S. Geological Survey of the Territories Bulletin 1(2):3-48.

- Eaton, G. F. 1903. The characters of Pteranodon. American Journal of Science, ser. 4, 16(91):82-86, pl. 6-7.

- Eaton, G. F. 1904. The characters of Pteranodon (second paper). American Journal of Science, ser. 4, 17(100):318-320, pl. 19-20.

- Eaton, G. F. 1908. The skull of Pteranodon. Science (n. s.) XXVII 254-255.

- Everhart, M. J. 1999. An early occurrence of Pteranodon sternbergi from the Smoky Hill Member (Late Cretaceous) of the Niobrara Chalk in western Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 18(Abstracts):27.

- Everhart, M. J. 2005. Oceans of Kansas - A Natural History of the Western Interior Sea. Indiana University Press, 320 pp.

- Harksen, J. C. 1966. Pteranodon sternbergi, a new fossil pterodactyl from the Niobrara Cretaceous of Kansas. Proceedings South Dakota Academy of Science 45:74-77.

- Kripp, D. von. 1943. "Ein Lebensbild von Pteranodon ingens auf flugtechnischer Grundlage", Nova Acta Leopoldina, N.F., 12(83): 16-32

- Lane, H. H. 1946. A survey of the fossil vertebrates of Kansas, Part III, The Reptiles, Kansas Academy Science, Transactions 49(3):289-332, figs. 1-7.

- Marsh, O. C. 1871. Scientific expedition to the Rocky Mountains. American Journal of Science ser. 3, 1(6):142-143.

- Marsh, O. C. 1871. Notice of some new fossil reptiles from the Cretaceous and Tertiary formations. American Journal of Science, Series 3, 1(6):447-459.

- Marsh, O. C. 1871. Note on a new and gigantic species of Pterodactyle. American Journal of Science, Series 3, 1(6):472.

- Marsh, O. C. 1872. Discovery of additional remains of Pterosauria, with descriptions of two new species. American Journal of Science, Series 3, 3(16) :241-248.

- Marsh, O. C. 1881. Note on American pterodactyls. American Journal of Science, Series 3, 21(124):342-343.

- Marsh, O. C. 1882. The wings of Pterodactyles. American Journal of Science, Series 3, 23(136):251-256, pl. III.

- Marsh, O. C. 1884. Principal characters of American Cretaceous pterodactyls. Part I. The skull of Pteranodon. American Journal of Science, Series 3, 27(161):422-426, pl. 15.

- Miller, H. W. 1971. The taxonomy of the Pteranodon species from Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 74(1):1-19.

- Miller, H. W. 1971. A skull of Pteranodon (Longicepia) longiceps Marsh associated with wing and body parts. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions 74(10):20-33.

- Padian, K. 1983. A functional analysis of flying and walking in pterosaurs. Paleobiology 9(3):218-239.

- Russell, D. A. 1988. A check list of North American marine cretaceous vertebrates Including fresh water fishes, Occasional Paper of the Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology, (4):57.

- Schultze, H.-P., L. Hunt, J. Chorn and A. M. Neuner, 1985. Type and figured specimens of fossil vertebrates in the collection of the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History, Part II. Fossil Amphibians and Reptiles. Miscellaneous Publications of the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History 77:66 pp.

- Seeley, Harry G. 1871. Additional evidence of the structure of the head in ornithosaurs from the Cambridge Upper Greensand; being a supplement to "The Ornithosauria." The Annals and Magazine of Natural History, Series 4, 7:20-36, pls. 2-3. (Discovery of toothless pterosaurs in England)

- Shor, E. N. 1971. Fossils and flies; The life of a compleat scientist - Samuel Wendell Williston, 1851–1918, University of Oklahoma Press, 285 pp.

- Sternberg, C. H. 1990. The life of a fossil hunter, Indiana University Press, 286 pp. (Originally published in 1909 by Henry Holt and Company)

- Sternberg, G. F. and M. V. Walker. 1958. Observation of articulated limb bones of a recently discovered Pteranodon in the Niobrara Cretaceous of Kansas. Kansas Academy of Science, Transactions, 61(1):81-85.

- Stewart, J. D. 1990. Niobrara Formation vertebrate stratigraphy. pp. 19–30 in Bennett, S. C. (ed.), Niobrara Chalk Excursion Guidebook, The University of Kansas Museum of Natural History and the Kansas Geological Survey.

- Wang, X. and Z. Zhou. 2004. Pterosaur embryo from the Early Cretaceous. Nature 429:621.

- Wellnhofer, P. 1991. The illustrated encyclopedia of pterosaurs. Crescent Books, New York, 192 pp.

- Williston, S. W. 1891. The skull and hind extremity of Pteranodon. American Naturalist 25(300):1124-1126.

- Williston, S. W. 1892. Kansas pterodactyls. Part I. Kansas University Quarterly 1:1-13, pl. i.

- Williston, S. W. 1893. Kansas pterodactyls. Part II. Kansas University Quarterly 2:79-81, with 1 fig.

- Williston, S. W. 1895. Note on the mandible of Ornithostoma. Kansas University Quarterly 4:61.

- Williston, S. W. 1896. On the skull of Ornithostoma. Kansas University Quarterly 4(4):195-197, with pl. i.

- Williston, S. W. 1897. Restoration of Ornithostoma (Pteranodon). Kansas University Quarterly 6:35-51, with pl. ii.

- Williston, S. W. 1902. On the skeleton of Nyctodactylus, with restoration. American Journal of Anatomy. 1:297-305.

- Williston, S. W. 1902. On the skull of Nyctodactylus, an Upper Cretaceous pterodactyl. Journal of Geology, 10:520-531, 2 pls.

- Williston, S. W. 1902. Winged reptiles. Pop. Science Monthly 60:314-322, 2 figs.

- Williston, S. W. 1903. On the osteology of Nyctosaurus (Nyctodactylus), with notes on American pterosaurs. Field Mus. Publ. (Geological Ser.) 2(3):125-163, 2 figs., pls. XL-XLIV.

- Williston, S. W., 1904. The fingers of pterodactyls. Geology Magazine, Series 5, 1(2): 5:59-60.

- Williston, S. W. 1911 The wing-finger of pterodactyls, with restoration of Nyctosaurus. Journal of Geology. 19:696–705.

- Williston, S. W. 1912. A review of G. B. Eaton's "Osteology of Pteranodon". Journal of Geology. 20:288.