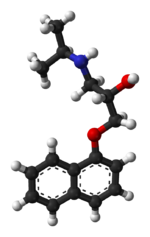

Propranolol

An 80 mg capsule of Propranolol.

Propranolol (INN) is a non-selective beta blocker mainly used in the treatment of hypertension. It was the first successful beta blocker developed. Propranolol is available in generic form as propranolol hydrochloride, as well as an AstraZeneca and Wyeth product under the trade names Inderal, Inderal LA, Avlocardyl (also available in prolonged absorption form named "Avlocardyl Retard"), Deralin, Dociton, Inderalici, InnoPran XL, Sumial, Anaprilinum (depending on marketplace and release rate), Bedranol SR (sandoz).

Propranolol is one of the banned substances in the Olympics, presumably for its use in controlling stage fright and tremors. It was taken by Kim Jong-su, a North Korean pistol shooter who won two medals at the 2008 Olympic Games. He was the first Olympic shooter to be disqualified for drug use.[1]

History and development

Scottish scientist James W. Black successfully developed propranolol in the late 1950s. In 1988, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine for this discovery. Propranolol was derived from the early β-adrenergic antagonists dichloroisoprenaline and pronethalol. The key structural modification, which was carried through to essentially all subsequent beta blockers, was the insertion of a methoxy bridge into the arylethanolamine structure of pronethalol thus greatly increasing the potency of the compound. This also apparently eliminated the carcinogenicity found with pronethalol in animal models.

Newer, more selective beta-blockers (such as nebivolol) are now used in the treatment of hypertension.

Indications

Propranolol is indicated for the management of various conditions including:

- There has been some experimentation in psychiatric areas:[2]

- Glaucoma

While once first-line treatment for hypertension, the role for beta-blockers was downgraded in June 2006 in the United Kingdom to fourth-line as they perform less well than other drugs, particularly in the elderly, and evidence is increasing that the most frequently used beta-blockers at usual doses carry an unacceptable risk of provoking type 2 diabetes. [7]

Propranolol is also used to lower portal vein pressure in portal hypertension and prevent esophageal variceal bleeding.

Off-label and investigational use

Propranolol is often used by musicians and other performers to prevent stage fright. It has been taken by surgeons to reduce their own innate hand tremors during surgery.[8]

Propranolol is currently being investigated as a potential treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder.[9][10][11] Propranolol works to inhibit the actions of norepinephrine, a neurotransmitter that enhances memory consolidation. Studies have shown that individuals given propranolol immediately after a traumatic experience show less severe symptoms of PTSD compared to their respective control groups that did not receive the drug (Vaiva et al., 2003). However, results remain inconclusive as to the success of propranolol in treatment of PTSD.

Recent evidence (June 2008) suggests that propranolol can be used to treat severe infantile hemangiomas (IHs).[12] This treatment has proven superior to corticosteroids, as propranolol has fewer side effects and is more effective when treating IHs.

Propranolol along with a number of other membrane-acting drugs have been investigated for possible effects on Plasmodium falciparum and so the treatment of malaria. In vitro positive effects until recently had not been matched by useful in vivo anti-parasite activity against P. vinckei,[13] or P. yoelii nigeriensis.[14] However a single study from 2006 has suggested that propranolol may reduce the dosages required for existing drugs to be effective against P. falciparum by 5- to 10-fold, suggesting a role for combination therapies.[15]

Precautions and contraindications

Propranolol should be used with caution in patients with:[16]

Propranolol is contraindicated in patients with:[16]

Adverse effects

Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) associated with propranolol therapy are similar to other lipophilic beta blockers (see beta blocker).

Pregnancy and lactation

Propranolol, like other beta blockers, is classified as Pregnancy category C in the United States and ADEC Category C in Australia. Beta-blocking agents in general reduce perfusion of the placenta which may lead to adverse outcomes for the neonate, including pulmonary or cardiac complications, or premature birth. The newborn may experience additional adverse effects such as hypoglycemia and bradycardia.

Most beta-blocking agents appear in the milk of lactating women. This is especially the case for a lipophilic drug like propranolol. Breastfeeding is not recommended in patients receiving propranolol therapy.

Pharmacokinetics

Propranolol is rapidly and completely absorbed, with peak plasma levels achieved approximately 1–3 hours after ingestion. Co-administration with food appears to enhance bioavailability. Despite complete absorption, propranolol has a variable bioavailability due to extensive first-pass metabolism. Hepatic impairment will therefore increase its bioavailability. The main metabolite 4-hydroxypropranolol, with a longer half-life (5.2–7.5 hours) than the parent compound (3–4 hours), is also pharmacologically active.

Propranolol is a highly lipophilic drug achieving high concentrations in the brain. The duration of action of a single oral dose is longer than the half-life and may be up to 12 hours, if the single dose is high enough (e.g., 80 mg). Effective plasma concentrations are between 10–100 ng/mL.

Toxic levels are associated with plasma concentrations above 2000 ng/ml.

Mechanism of action

Propranolol is a non-selective beta blocker, that is, it blocks the action of epinephrine and norepinephrine on both β1- and β2-adrenergic receptors. It has little intrinsic sympathomimetic activity (ISA) but has strong membrane stabilizing activity (only at high blood concentrations, eg overdosage). Research has also shown that propranolol has inhibitory effects on the norepinephrine transporter and/or stimulates norepinephrine release (present experiments have shown that the concentration of norepinephrine is increased in the synapse but do not have the ability to discern which effect is taking place).[17] Since propranolol blocks β-adrenoceptors, the increase in synaptic norepinephrine only results in α-adrenergic activation, with the α1-adrenoceptor being particularly important for effects observed in animal models. Therefore, some have suggested that it be looked upon as an indirect α1 agonist as well as a β antagonist. Probably owing to the effect at the α1-adrenoceptor, the racemate and the individual enantiomers of propranolol have been shown to substitute for cocaine in rats, with the most potent enantiomer being S-(–)-propranolol. Both enantiomers of the drug have a local anesthetic (topical) effect. In addition, some evidence suggests that propranolol may function as a partial agonist at one or more serotonin receptors (possibly 5-HT1B).

Interactions

Beta blockers, including propranolol, have an additive effect with other drugs which decrease blood pressure, or which decrease cardiac contractility or conductivity. Clinically-significant interactions particularly occur with:[16]

Dosage

The usual maintenance dose ranges for oral propranolol therapy vary by indication:

- Hypertension, angina, essential tremor

- 120–320 mg daily in divided doses

- Sustained-release formulations are available in some markets.

- Migraine Prophylaxis

- The initial dose is 80 mg Inderal daily in divided doses. The usual effective dose range is 160 mg to 240 mg per day.

- The dosage may be increased gradually to achieve optimum migraine prophylaxis. If a satisfactory response is not obtained within four to six weeks after reaching the maximum dose, Inderal therapy should be discontinued.

- Tachyarrhythmia, anxiety (GAD), hyperthyroidism

- Performance anxiety

- 5–10 mg 30min or 1.5hrs before and after performance, optionally 5–10 mg night before. Up to 40 mg if necessary, but side-effects may present.[19]

Intravenous (IV) propranolol may be used in acute arrhythmia or thyrotoxic crisis.[20]

References

- ↑ http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=olympics-shooter-doping-propranolol

- ↑ Kornischka J, Cordes J, Agelink MW (April 2007). "[40 years beta-adrenoceptor blockers in psychiatry]" (in German). Fortschritte Der Neurologie-Psychiatrie 75 (4): 199–210. doi:10.1055/s-2006-944295. PMID 17200914.

- ↑ Vieweg V, Pandurangi A, Levenson J, Silverman J (1994). "The consulting psychiatrist and the polydipsia-hyponatremia syndrome in schizophrenia". International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 24 (4): 275–303. PMID 7737786.

- ↑ Kishi Y, Kurosawa H, Endo S (1998). "Is propranolol effective in primary polydipsia?". International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 28 (3): 315–25. PMID 9844835.

- ↑ Kramer MS, Gorkin R, DiJohnson C (1989). "Treatment of neuroleptic-induced akathisia with propranolol: a controlled replication study". The Hillside Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 11 (2): 107–19. PMID 2577308.

- ↑ Thibaut F, Colonna L (1993). "[Anti-aggressive effect of beta-blockers]" (in French). L'Encéphale 19 (3): 263–7. PMID 7903928.

- ↑ Sheetal Ladva (2006-06-28). "NICE and BHS launch updated hypertension guideline". National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. http://www.nice.org.uk/download.aspx?o=335988. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- ↑ Elman MJ, Sugar J, Fiscella R, et al. (1998). "The effect of propranolol versus placebo on resident surgical performance". Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society 96: 283–91; discussion 291–4. PMID 10360293.

- ↑ "Doctors test a drug to ease traumatic memories - Mental Health - MSNBC.com". http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/10806799/. Retrieved 2007-06-30.

- ↑ Brunet A, Orr SP, Tremblay J, Robertson K, Nader K, Pitman RK (2007). "Effect of post-retrieval propranolol on psychophysiologic responding during subsequent script-driven traumatic imagery in post-traumatic stress disorder". Journal of Psychiatric Research 42 (6): 503. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.05.006. PMID 17588604.

- ↑ Brunet A, Orr SP, Tremblay J, Robertson K, Nader K, Pitman RK (May 2008). "Effect of post-retrieval propranolol on psychophysiologic responding during subsequent script-driven traumatic imagery in post-traumatic stress disorder". Journal of Psychiatric Research 42 (6): 503–6. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.05.006. PMID 17588604.

- ↑ Léauté-Labrèze C et al. (June 2008). "Propranolol for Severe Hemangiomas of Infancy". New England Journal of Medicine 358 (24): 2649–2651. doi:10.1056/NEJMc0708819. PMID 18550886.

- ↑ Ohnishi S, Sadanaga K, Katsuoka M, Weidanz W (1990). "Effects of membrane acting-drugs on plasmodium species and sickle cell erythrocytes". Mol Cell Biochem 91 (1-2): 159–65. doi:10.1007/BF00228091. PMID 2695829.

- ↑ Singh N, Puri S (2000). "Interaction between chloroquine and diverse pharmacological agents in chloroquine resistant Plasmodium yoelii nigeriensis". Acta Trop 77 (2): 185–93. doi:10.1016/S0001-706X(00)00133-9. PMID 11080509.

- ↑ Murphy S, Harrison T, Hamm H, Lomasney J, Mohandas N, Haldar K (December 2006). "Erythrocyte G protein as a novel target for malarial chemotherapy". PLoS Med 3 (12): e528. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030528. PMID 17194200.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Rossi S, editor. Australian Medicines Handbook 2006. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook; 2006.

- ↑ Young R, Glennon RA (April 2009). "S(-)Propranolol as a discriminative stimulus and its comparison to the stimulus effects of cocaine in rats". Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 203 (2): 369–82. doi:10.1007/s00213-008-1317-2. PMID 18795268.

- ↑ van Harten J (1995). "Overview of the pharmacokinetics of fluvoxamine". Clinical Pharmacokinetics 29 (Suppl 1): 1–9. doi:10.2165/00003088-199500291-00003. PMID 8846617.

- ↑ Laverdure B, Boulenger JP (1991). "[Beta-blocking drugs and anxiety. A proven therapeutic value]" (in French). L'Encéphale 17 (5): 481–92. PMID 1686251.

- ↑ *Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary, 47th edition. London: British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain; 2004.

External links

|

Sympatholytic (and closely related) antihypertensives (C02) |

|

Sympatholytics

(antagonize α-adrenergic

vasoconstriction) |

|

Central

|

|

α2 agonist

|

|

|

|

Adrenergic release inhibitors

|

Bethanidine • Bretylium • Debrisoquine • Guanadrel • Guanazodine • Guanethidine • Guanoclor • Guanoxan • Guanazodine • Guanoxabenz • Guanoxan

|

|

|

Imidazoline receptor agonist

|

Moxonidine • Rilmenidine

|

|

|

Ganglion-blocking/nicotinic antagonist

|

Mecamylamine • Pentolinium • Trimethaphan

|

|

|

|

Peripheral

|

|

Indirect

|

|

|

Pargyline

|

|

|

Adrenergic uptake inhibitor

|

|

|

|

Tyrosine hydroxylase inhibitor

|

Metirosine

|

|

|

|

Direct

|

|

α1 blockers

|

Prazosin • Indoramin • Trimazosin • Doxazosin • Urapidil

|

|

|

Non-selective α blocker

|

Phentolamine

|

|

|

|

|

| Other antagonists |

|

Serotonin antagonist

|

Ketanserin

|

|

Endothelin antagonist (for PH) |

dual (Bosentan) • selective (Ambrisentan, Sitaxentan)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

anat(a:h,u,t,a,l,v:h,u,t,a,l)/phys/devp/cell/

|

|

proc, drug(C2s/,C3,C4,C5,,C8,C9)

|

|

|

|

|

Anxiolytics (N05B) |

|

| GABAA PAMs |

|

|

Adinazolam • Alprazolam • Bretazenil • Bromazepam • Camazepam • Chlordiazepoxide • Clobazam • Clonazepam • Clorazepate • Clotiazepam • Cloxazolam • Diazepam • Ethyl Loflazepate • Etizolam • Fludiazepam • Halazepam • Imidazenil • Ketazolam • Lorazepam • Medazepam • Nordazepam • Oxazepam • Pinazepam • Prazepam |

|

|

Carbamates

|

Emylcamate • Mebutamate • Meprobamate (Carisoprodol, Tybamate) • Phenprobamate • Procymate

|

|

|

Nonbenzodiazepines

|

Abecarnil • Adipiplon • Alpidem • CGS-9896 • CGS-20625 • Divaplon • ELB-139 • Fasiplon • GBLD-345 • Gedocarnil • L-838,417 • NS-2664 • NS-2710 • Ocinaplon • Pagoclone • Panadiplon • Pipequaline • RWJ-51204 • SB-205,384 • SL-651,498 • Taniplon • TP-003 • TP-13 • TPA-023 • Y-23684 • ZK-93423

|

|

|

Pyrazolopyridines

|

Cartazolate • Etazolate • ICI-190,622 • Tracazolate

|

|

|

Others

|

|

|

|

| α2δ VDCC Blockers |

|

|

| 5-HT1A Agonists |

Azapirones: Buspirone • Gepirone • Tandospirone; Others: Flesinoxan • Oxaflozane

|

|

| H1 Antagonists |

Diphenylmethanes: Captodiame • Hydroxyzine; Others: Brompheniramine • Chlorpheniramine • Pheniramine

|

|

| CRH1 Antagonists |

Antalarmin • CP-154,526 • Pexacerfont • Pivagabine

|

|

| NK2 Antagonists |

GR-159,897 • Saredutant

|

|

| MCH1 antagonists |

ATC-0175 • SNAP-94847

|

|

| mGluR2/3 Agonists |

Eglumegad

|

|

| mGluR5 NAMs |

Fenobam

|

|

| TSPO agonists |

DAA-1097 • DAA-1106 • Emapunil • FGIN-127 • FGIN-143

|

|

| σ1 agonists |

Afobazole • Opipramol

|

|

| Others |

Benzoctamine • Carbetocin • Demoxytocin • Mephenoxalone • Mepiprazole • Oxanamide • Oxytocin • Promoxolane • Tofisopam • Trimetozine • WAY-267,464 |

|

#WHO-EM. ‡Withdrawn from market. Clinical trials: †Phase III. §Never to phase III

|

|

|

dsrd (o, p, m, p, a, d, s), sysi/, spvo

|

|

|

|

|

|

Adrenergics |

|

|

Receptor ligands |

|

|

α1

|

Agonists: 5-FNE • 6-FNE • Amidephrine • Anisodamine • Anisodine • Cirazoline • Dipivefrine • Dopamine • Ephedrine • Epinephrine (Adrenaline) • Etilefrine • Ethylnorepinephrine • Indanidine • Levonordefrin • Metaraminol • Methoxamine • Methyldopa • Midodrine • Naphazoline • Norepinephrine (Noradrenaline) • Octopamine • Oxymetazoline • Phenylephrine • Phenylpropanolamine • Pseudoephedrine • Synephrine • Tetrahydrozoline

Antagonists: Abanoquil • Adimolol • Ajmalicine • Alfuzosin • Amosulalol • Arotinolol • Atiprosin • Benoxathian • Buflomedil • Bunazosin • Carvedilol • CI-926 • Corynanthine • Dapiprazole • DL-017 • Domesticine • Doxazosin • Eugenodilol • Fenspiride • GYKI-12,743 • GYKI-16,084 • Indoramin • Ketanserin • L-765,314 • Labetalol • Mephendioxan • Metazosin • Monatepil • Moxisylyte (Thymoxamine) • Naftopidil • Nantenine • Neldazosin • Nicergoline • Niguldipine • Pelanserin • Phendioxan • Phenoxybenzamine • Phentolamine • Piperoxan • Prazosin • Quinazosin • Ritanserin • RS-97,078 • SGB-1,534 • Silodosin • SL-89.0591 • Spiperone • Talipexole • Tamsulosin • Terazosin • Tibalosin • Tiodazosin • Tipentosin • Tolazoline • Trimazosin • Upidosin • Urapidil • Zolertine

* Note that many TCAs, TeCAs, antipsychotics, ergolines, and some piperazines like buspirone, trazodone, nefazodone, etoperidone, and mepiprazole all antagonize α1-adrenergic receptors as well, which contributes to their side effects such as orthostatic hypotension.

|

|

|

α2

|

Agonists: (R)-3-Nitrobiphenyline • 4-NEMD • 6-FNE • Amitraz • Apraclonidine • Brimonidine • Clonidine • Detomidine • Dexmedetomidine • Dihydroergotamine • Dipivefrine • Dopamine • Ephedrine • Ergotamine • Epinephrine (Adrenaline) • Esproquin • Etilefrine • Ethylnorepinephrine • Guanabenz • Guanfacine • Guanoxabenz • Levonordefrin • Lofexidine • Medetomidine • Methyldopa • Mivazerol • Naphazoline • Norepinephrine (Noradrenaline) • Phenylpropanolamine • Piperoxan • Pseudoephedrine • Rilmenidine • Romifidine • Talipexole • Tetrahydrozoline • Tizanidine • Tolonidine • Urapidil • Xylazine • Xylometazoline

Antagonists: 1-PP • Adimolol • Aptazapine • Atipamezole • BRL-44408 • Buflomedil • Cirazoline • Efaroxan • Esmirtazapine • Fenmetozole • Fluparoxan • GYKI-12,743 • GYKI-16,084 • Idazoxan • Mianserin • Mirtazapine • MK-912 • NAN-190 • Olanzapine • Phentolamine • Phenoxybenzamine • Piperoxan • Piribedil • Rauwolscine • Rotigotine • SB-269,970 • Setiptiline • Spiroxatrine • Sunepitron • Tolazoline • Yohimbine

* Note that many atypical antipsychotics and azapirones like buspirone and gepirone (via metabolite 1-PP) antagonize α2-adrenergic receptors as well.

|

|

|

|

Agonists: 2-FNE • 5-FNE • Amibegron • Arbutamine • Arformoterol • Arotinolol • BAAM • Bambuterol • Befunolol • Bitolterol • Broxaterol • Buphenine • Carbuterol • Cimaterol • Clenbuterol • Denopamine • Deterenol • Dipivefrine • Dobutamine • Dopamine • Dopexamine • Ephedrine • Epinephrine (Adrenaline) • Etafedrine • Etilefrine • Ethylnorepinephrine • Fenoterol • Formoterol • Hexoprenaline • Higenamine • Indacaterol • Isoetarine • Isoprenaline (Isoproterenol) • Isoxsuprine • Labetalol • Levonordefrin • Levosalbutamol • Mabuterol • Methoxyphenamine • Methyldopa • N-Isopropyloctopamine • Norepinephrine (Noradrenaline) • Orciprenaline • Oxyfedrine • Phenylpropanolamine • Pirbuterol • Prenalterol • Ractopamine • Procaterol • Pseudoephedrine • Reproterol • Rimiterol • Ritodrine • Salbutamol (Albuterol) • Salmeterol • Solabegron • Terbutaline • Tretoquinol • Tulobuterol • Xamoterol • Zilpaterol • Zinterol

Antagonists: Acebutolol • Adaprolol • Adimolol • Afurolol • Alprenolol • Alprenoxime • Amosulalol • Ancarolol • Arnolol • Arotinolol • Atenolol • Befunolol • Betaxolol • Bevantolol • Bisoprolol • Bopindolol • Bormetolol • Bornaprolol • Brefonalol • Bucindolol • Bucumolol • Bufetolol • Buftiralol • Bufuralol • Bunitrolol • Bunolol • Bupranolol • Burocrolol • Butaxamine • Butidrine • Butofilolol • Capsinolol • Carazolol • Carpindolol • Carteolol • Carvedilol • Celiprolol • Cetamolol • Cicloprolol • Cinamolol • Cloranolol • Cyanopindolol • Dalbraminol • Dexpropranolol • Diacetolol • Dichloroisoprenaline • Dihydroalprenolol • Dilevalol • Diprafenone • Draquinolol • Dropranolol • Ecastolol • Epanolol • Ericolol • Ersentilide • Esatenolol • Esmolol • Esprolol • Eugenodilol • Exaprolol • Falintolol • Flestolol • Flusoxolol • Hydroxycarteolol • Hydroxytertatolol • ICI-118,551 • Idropranolol • Indenolol • Indopanolol • Iodocyanopindolol • Iprocrolol • Isoxaprolol • Isamoltane • Labetalol • Landiolol • Levobetaxolol • Levobunolol • Levocicloprolol • Levomoprolol • Medroxalol • Mepindolol • Metalol • Metipranolol • Metoprolol • Moprolol • Nadolol • Nadoxolol • Nafetolol • Nebivolol • Neraminol • Nifenalol • Nipradilol • Oberadilol • Oxprenolol • Pacrinolol • Pafenolol • Pamatolol • Pargolol • Parodilol • Penbutolol • Penirolol • PhQA-33 • Pindolol • Pirepolol • Practolol • Primidolol • Procinolol • Pronethalol • Propafenone • Propranolol • Ridazolol • Ronactolol • Soquinolol • Sotalol • Spirendolol • SR 59230A • Sulfinalol • TA-2005 • Talinolol • Tazolol • Teoprolol • Tertatolol • Terthianolol • Tienoxolol • Tilisolol • Timolol • Tiprenolol • Tolamolol • Toliprolol • Tribendilol • Trigevolol • Xibenolol • Xipranolol

|

|

|

|

|

Reuptake inhibitors |

|

|

NET

|

Selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors: Amedalin • Atomoxetine (Tomoxetine) • Ciclazindol • Daledalin • Esreboxetine • Lortalamine • Mazindol • Nisoxetine • Reboxetine • Talopram • Talsupram • Tandamine • Viloxazine; Norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors: Amineptine • Bupropion (Amfebutamone) • Fencamine • Fencamfamine • Lefetamine • Levophacetoperane • LR-5182 • Manifaxine • Methylphenidate • Nomifensine • O-2172 • Radafaxine; Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors: Bicifadine • Desvenlafaxine • Duloxetine • Eclanamine • Levomilnacipran • Milnacipran • Sibutramine • Venlafaxine; Serotonin-norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors: Brasofensine • Diclofensine • DOV-102,677 • DOV-21,947 • DOV-216,303 • JNJ-7925476 • JZ-IV-10 • Methylnaphthidate • Naphyrone • NS-2359 • PRC200-SS • SEP-225,289 • SEP-227,162 • Tesofensine; Tricyclic antidepressants: Amitriptyline • Butriptyline • Cianopramine • Clomipramine • Desipramine • Dosulepin • Doxepin • Imipramine • Lofepramine • Nortriptyline • Protriptyline • Trimipramine; Tetracyclic antidepressants: Amoxapine • Maprotiline • Mianserin • Oxaprotiline • Setiptiline; Others: Cocaine • CP-39,332 • EXP-561 • Fezolamine • Nefazodone • Nefopam • Pridefrine • Tapentadol • Tramadol • Ziprasidone

|

|

|

VMAT

|

|

|

|

|

|

Releasing agents |

|

Morpholines: Fenbutrazate • Morazone • Phendimetrazine • Phenmetrazine; Oxazolines: 4-Methylaminorex • Aminorex • Clominorex • Cyclazodone • Fenozolone • Fluminorex • Pemoline • Thozalinone; Phenethylamines (also amphetamines, cathinones, phentermines, etc): 2-OH-PEA • 4-CAB • 4-FA • 4-FMA • 4-MA • 4-MMA • Alfetamine • Amfecloral • Amfepentorex • Amfepramone • Amphetamine ( Dextroamphetamine, Levoamphetamine) • Amphetaminil • β-Me-PEA • BDB • Benzphetamine • BOH • Buphedrone • Butylone • Cathine • Cathinone • Clobenzorex • Clortermine • D-Deprenyl • Dimethylamphetamine • Dimethylcathinone (Dimethylpropion, metamfepramone) • DMA • DMMA • EBDB • Ephedrine • Ethcathinone • Ethylamphetamine • Ethylone • Famprofazone • Fenethylline • Fenproporex • Flephedrone • Fludorex • Furfenorex • Hordenine • IAP • IMP • L-Deprenyl (Selegiline) • Lisdexamfetamine • Lophophine • MBDB • MDA (Tenamfetamine) • MDEA • MDMA • MDMPEA • MDOH • MDPEA • Mefenorex • Mephedrone • Mephentermine • Methamphetamine ( Dextromethamphetamine, Levomethamphetamine) • Methcathinone • Methedrone • Methylone • NAP • Ortetamine • Paredrine • pBA • pCA • Pentorex (Phenpentermine) • Phenethylamine • Pholedrine • Phenpromethamine • Phentermine • Phenylpropanolamine • pIA • Prenylamine • Propylamphetamine • Pseudoephedrine • Tiflorex • Tyramine • Xylopropamine • Zylofuramine; Piperazines: 2C-B-BZP • BZP • MBZP • mCPP • MDBZP • MeOPP • pFPP; Others: 2-Amino-1,2-dihydronaphthalene • 2-Aminoindane • 2-Aminotetralin • 2-Benzylpiperidine • 4-Benzylpiperidine • 5-IAI • Clofenciclan • Cyclopentamine • Cypenamine • Cyprodenate • Feprosidnine • Gilutensin • Heptaminol • Hexacyclonate • Indanorex • Isometheptene • Methylhexanamine • Octodrine • Phthalimidopropiophenone • Propylhexedrine (Levopropylhexedrine) • Tuaminoheptane

|

|

|

|

Enzyme inhibitors |

|

|

|

|

PAH

|

3,4-Dihydroxystyrene

|

|

|

TH

|

3-Iodotyrosine • Aquayamycin • Bulbocapnine • Metirosine • Oudenone

|

|

|

AAAD

|

Benserazide • Carbidopa • Genistein • Methyldopa

|

|

|

DBH

|

Bupicomide • Disulfiram • Dopastin • Fusaric acid • Nepicastat • Phenopicolinic acid • Tropolone

|

|

|

PNMT

|

CGS-19281A • SKF-64139 • SKF-7698

|

|

|

|

|

|

MAO

|

Nonselective: Benmoxin • Caroxazone • Echinopsidine • Furazolidone • Hydralazine • Indantadol • Iproclozide • Iproniazid • Isocarboxazid • Isoniazid • Linezolid • Mebanazine • Metfendrazine • Nialamide • Octamoxin • Paraxazone • Phenelzine • Pheniprazine • Phenoxypropazine • Pivalylbenzhydrazine • Procarbazine • Safrazine • Tranylcypromine; MAO-A selective: Amiflamine • Bazinaprine • Befloxatone • Befol • Brofaromine • Cimoxatone • Clorgiline • Esuprone • Harmala alkaloids (Harmine, Harmaline, Tetrahydroharmine, Harman, Norharman, etc) • Methylene Blue • Metralindole • Minaprine • Moclobemide • Pirlindole • Sercloremine • Tetrindole • Toloxatone • Tyrima; MAO-B selective: D-Deprenyl • Selegiline (L-Deprenyl) • Ladostigil • Lazabemide • Milacemide • Mofegiline • Pargyline • Rasagiline

* Note that MAO-B inhibitors also influence norepinephrine/epinephrine levels since they inhibit the breakdown of their precursor dopamine.

|

|

|

COMT

|

Entacapone • Tolcapone

|

|

|

|

|

|

Others |

|

|

Precursors

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Others

|

Activity enhancers: BPAP • PPAP; Release blockers: Bethanidine • Bretylium • Guanadrel • Guanazodine • Guanclofine • Guanethidine • Guanoxan; Toxins: Oxidopamine (6-Hydroxydopamine)

|

|

|

|

|

Serotonergics |

|

|

5-HT1 receptor ligands |

|

|

5-HT1A

|

Agonists: Azapirones: Alnespirone • Binospirone • Buspirone • Enilospirone • Eptapirone • Gepirone • Ipsapirone • Perospirone • Revospirone • Tandospirone • Tiospirone • Umespirone • Zalospirone; Antidepressants: Etoperidone • Nefazodone • Trazodone; Antipsychotics: Aripiprazole • Asenapine • Clozapine • Quetiapine • Ziprasidone; Ergolines: Dihydroergotamine • Ergotamine • Lisuride • Methysergide • LSD; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MeO-DMT • 5-MT • Bufotenin • DMT • Psilocin • Psilocybin; Others: 8-OH-DPAT • Adatanserin • Befiradol • BMY-14802 • Cannabidiol • Dimemebfe • Ebalzotan • Eltoprazine • F-11,461 • F-12,826 • F-13,714 • F-14,679 • F-15,063 • F-15,599 • Flesinoxan • Flibanserin • Lesopitron • Lu AA21004 • LY-293,284 • LY-301,317 • MKC-242 • NBUMP • Osemozotan • Oxaflozane • Pardoprunox • Piclozotan • Rauwolscine • Repinotan • Roxindole • RU-24,969 • S 14,506 • S-14,671 • S-15,535 • Sarizotan • SSR-181,507 • Sunepitron • U-92016A • Urapidil • Vilazodone • Xaliproden • Yohimbine

Antagonists: Antipsychotics: Iloperidone • Risperidone • Sertindole; Beta blockers: Alprenolol • Cyanopindolol • Iodocyanopindolol • Oxprenolol • Pindobind • Pindolol • Propranolol • Tertatolol; Others: AV965 • BMY-7378 • CSP-2503 • Dotarizine • Flopropione • GR-46611 • Isamoltane • Lecozotan • Metitepine/Methiothepin • MPPF • NAN-190 • PRX-00023 • Robalzotan • S-15535 • SB-649915 • SDZ 216-525 • Spiperone • Spiramide • Spiroxatrine • UH-301 • WAY-100,135 • WAY-100,635 • Xylamidine

|

|

|

5-HT1B

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: Dihydroergotamine • Ergotamine • Methysergide; Piperazines: Eltoprazine • TFMPP; Triptans: Avitriptan • Eletriptan • Sumatriptan • Zolmitriptan; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MT; Others: CGS-12066A • CP-93,129 • CP-94,253 • CP-135,807 • RU-24969

Antagonists: Lysergamides: Metergoline; Others: AR-A000002 • Elzasonan • GR-127,935 • Isamoltane • Metitepine/Methiothepin • SB-216,641 • SB-224,289 • SB-236,057 • Yohimbine

|

|

|

5-HT1D

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: Dihydroergotamine • Methysergide; Triptans: Almotriptan • Avitriptan • Eletriptan • Frovatriptan • Naratriptan • Rizatriptan • Sumatriptan • Zolmitriptan; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MT; Others: CP-135,807 • CP-286,601 • GR-46611 • L-694,247 • L-772,405 • PNU-109,291 • PNU-142,633

Antagonists: Lysergamides: Metergoline; Others: Alniditan • BRL-15572 • Elzasonan • GR-127,935 • Ketanserin • LY-310,762 • LY-367,642 • LY-456,219 • LY-456,220 • Metitepine/Methiothepin • Ritanserin • Yohimbine • Ziprasidone

|

|

|

5-HT1E

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: Methysergide; Triptans: Eletriptan; Tryptamines: BRL-54443 • Tryptamine

Antagonists: Metitepine/Methiothepin

|

|

|

5-HT1F

|

Agonists: Triptans: Eletriptan • Naratriptan • Sumatriptan; Tryptamines: 5-MT; Others: BRL-54443 • Lasmiditan • LY-334,370

Antagonists: Metitepine/Methiothepin

|

|

|

|

|

5-HT2 receptor ligands |

|

|

|

5-HT2A

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: ALD-52 • Ergonovine • Lisuride • LA-SS-Az • LSD • LSD-Pip • Lysergic acid 2-butyl amide • Methysergide; Phenethylamines: 25I-NBMD • 25I-NBOH • 25I-NBOMe • 2C-B • 2C-B-FLY • 2CB-Ind • 2C-E • 2C-I • 2C-T-2 • 2C-T-7 • 2C-T-21 • 2CBCB-NBOMe • 2CBFly-NBOMe • Bromo-DragonFLY • DOB • DOC • DOI • DOM • MDA • MDMA • Mescaline • TCB-2 • TFMFly; Piperazines: BZP • Quipazine • TFMPP; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MeO-α-ET • 5-MeO-α-MT • 5-MeO-DET • 5-MeO-DiPT • 5-MeO-DMT • 5-MeO-DPT • 5-MT • α-ET • α-Methyl-5-HT • α-MT • Bufotenin • DET • DiPT • DMT • DPT • Psilocin • Psilocybin; Others: AL-34662 • AL-37350A • Dimemebfe • Medifoxamine • Oxaflozane • PNU-22394 • RH-34

Antagonists: Atypical antipsychotics: Amperozide • Aripiprazole • Carpipramine • Clocapramine • Clozapine • Gevotroline • Iloperidone • Melperone • Mosapramine • Olanzapine • Paliperidone • Pimozide • Quetiapine • Risperidone • Sertindole • Ziprasidone • Zotepine; Typical antipsychotics: Loxapine • Pipamperone; Antidepressants: Amitriptyline • Amoxapine • Aptazapine • Etoperidone • Mianserin • Mirtazapine • Nefazodone • Trazodone; Others: 5-I-R91150 • AC-90179 • Adatanserin • Altanserin • AMDA • APD-215 • Blonanserin • Cinanserin • CSP-2503 • Cyproheptadine • Deramciclane • Dotarizine • Eplivanserin • Esmirtazapine • Fananserin • Flibanserin • Ketanserin • KML-010 • Lubazodone • Mepiprazole • Metitepine/Methiothepin • Nantenine • Pimavanserin • Pizotifen • Pruvanserin • Rauwolscine • Ritanserin • S-14,671 • Sarpogrelate • Setoperone • Spiperone • Spiramide • SR-46349B • Volinanserin • Xylamidine • Yohimbine

|

|

|

5-HT2B

|

Agonists: Oxazolines: 4-Methylaminorex • Aminorex; Phenethylamines: Chlorphentermine • Cloforex • DOB • DOC • DOI • DOM • Fenfluramine • MDA • MDMA • Norfenfluramine; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MT • α-Methyl-5-HT; Others: BW-723C86 • Cabergoline • mCPP • Pergolide • PNU-22394 • Ro60-0175

Antagonists: Agomelatine • Asenapine • EGIS-7625 • Ketanserin • Lisuride • LY-272,015 • Metitepine/Methiothepin • PRX-08066 • Rauwolscine • Ritanserin • RS-127,445 • Sarpogrelate • SB-200,646 • SB-204,741 • SB-206,553 • SB-215,505 • SB-221,284 • SB-228,357 • SDZ SER-082 • Tegaserod • Yohimbine

|

|

|

5-HT2C

|

Agonists: Phenethylamines: 2C-B • 2C-E • 2C-I • 2C-T-2 • 2C-T-7 • 2C-T-21 • DOB • DOC • DOI • DOM • MDA • MDMA • Mescaline; Piperazines: Aripiprazole • mCPP • TFMPP; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MeO-α-ET • 5-MeO-α-MT • 5-MeO-DET • 5-MeO-DiPT • 5-MeO-DMT • 5-MeO-DPT • 5-MT • α-ET • α-Methyl-5-HT • α-MT • Bufotenin • DET • DiPT • DMT • DPT • Psilocin • Psilocybin; Others: A-372,159 • AL-38022A • CP-809,101 • Dimemebfe • Lorcaserin• Medifoxamine • MK-212 • ORG-37,684 • Oxaflozane • PNU-22394 • Ro60-0175 • Vabicaserin • WAY-629 • WAY-161,503 • YM-348

Antagonists: Atypical antipsychotics: Clozapine • Iloperidone • Melperone • Olanzapine • Paliperidone • Pimozide • Quetiapine • Risperidone • Sertindole • Ziprasidone • Zotepine; Typical antipsychotics: Chlorpromazine • Loxapine • Pipamperone; Antidepressants: Agomelatine • Amitriptyline • Amoxapine • Aptazapine • Etoperidone • Fluoxetine • Mianserin • Mirtazapine • Nefazodone • Nortriptyline • Trazodone; Others: Adatanserin • Cinanserin • Cyproheptadine • Deramciclane • Dotarizine • Eltoprazine • Esmirtazapine • FR-260,010 • Ketanserin • Ketotifen • Latrepirdine • Lu AA24530 • Metitepine/Methiothepin • Methysergide • Pizotifen • Ritanserin • RS-102,221 • S-14,671 • SB-200,646 • SB-206,553 • SB-221,284 • SB-228,357 • SB-242,084 • SB-243,213 • SDZ SER-082 • Xylamidine

|

|

|

|

|

5-HT3, 5-HT4, 5-HT5, 5-HT6, 5-HT7 ligands |

|

|

|

5-HT3

|

Agonists: Piperazines: BZP • Quipazine; Tryptamines: 2-Methyl-5-HT • 5-CT; Others: Chlorophenylbiguanide • Butanol • Ethanol • Halothane • Isoflurane • RS-56812 • SR-57,227 • SR-57,227-A • Toluene • Trichloroethane • Trichloroethanol • Trichloroethylene • YM-31636

Antagonists: Antiemetics: AS-8112 • Alosetron • Azasetron • Batanopride • Bemesetron • Cilansetron • Dazopride • Dolasetron • Granisetron • Lerisetron • Ondansetron • Palonosetron • Ramosetron • Renzapride • Tropisetron • Zacopride • Zatosetron; Atypical antipsychotics: Clozapine • Olanzapine • Quetiapine; Tetracyclic antidepressants: Amoxapine • Mianserin • Mirtazapine; Others: CSP-2503 • ICS-205,930 • Lu AA21004 • Lu AA24530 • MDL-72,222 • Memantine • Nitrous Oxide • Ricasetron • Sevoflurane • Thujone • Xenon

|

|

|

5-HT4

|

Agonists: Gastroprokinetic Agents: Cinitapride • Cisapride • Dazopride • Metoclopramide • Mosapride • Prucalopride • Renzapride • Tegaserod • Zacopride; Others: 5-MT • BIMU-8 • CJ-033,466 • PRX-03140 • RS-67333 • RS-67506 • SL65.0155 • TD-5108

Antagonists: GR-113,808 • GR-125,487 • L-Lysine • Piboserod • RS-39604 • RS-67532 • SB-203,186

|

|

|

5-HT5A

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: Ergotamine • LSD; Tryptamines: 5-CT; Others: Valerenic Acid

Antagonists: Asenapine • Latrepirdine • Metitepine/Methiothepin • Ritanserin • SB-699,551

* Note that the 5-HT5B receptor is not functional in humans.

|

|

|

5-HT6

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: Dihydroergotamine • Ergotamine • Lisuride • LSD • Mesulergine • Metergoline • Methysergide; Tryptamines: 2-Methyl-5-HT • 5-BT • 5-CT • 5-MT • Bufotenin • E-6801 • E-6837 • EMD-386,088 • EMDT • LY-586,713 • N-Methyl-5-HT • Tryptamine; Others: WAY-181,187 • WAY-208,466

Antagonists: Antidepressants: Amitriptyline • Amoxapine • Clomipramine • Doxepin • Mianserin • Nortriptyline; Atypical antipsychotics: Aripiprazole • Asenapine • Clozapine • Fluperlapine • Iloperidone • Olanzapine • Tiospirone; Typical antipsychotics: Chlorpromazine • Loxapine; Others: BGC20-760 • BVT-5182 • BVT-74316 • EGIS-12233 • GW-742,457 • Ketanserin • Latrepirdine • Lu AE58054 • Metitepine/Methiothepin • MS-245 • PRX-07034 • Ritanserin • Ro 04-6790 • Ro 63-0563 • SB-258,585 • SB-271,046 • SB-357,134 • SB-399,885 • SB-742,457

|

|

|

5-HT7

|

Agonists: Lysergamides: LSD; Tryptamines: 5-CT • 5-MT • Bufotenin; Others: 8-OH-DPAT • AS-19 • Bifeprunox • LP-12 • LP-44 • RU-24,969 • Sarizotan

Antagonists: Lysergamides: 2-Bromo-LSD • Bromocriptine • Dihydroergotamine • Ergotamine • Mesulergine • Metergoline • Methysergide; Antidepressants: Amitriptyline • Amoxapine • Clomipramine • Imipramine • Maprotiline • Mianserin; Atypical antipsychotics: Amisulpride • Aripiprazole • Clozapine • Olanzapine • Risperidone • Sertindole • Tiospirone • Ziprasidone • Zotepine; Typical antipsychotics: Chlorpromazine • Loxapine; Others: Butaclamol • EGIS-12233 • Ketanserin • LY-215,840 • Metitepine/Methiothepin • Pimozide • Ritanserin • SB-258,719 • SB-258,741 • SB-269,970 • SB-656,104 • SB-656,104-A • SB-691,673 • SLV-313 • SLV-314 • Spiperone • SSR-181,507

|

|

|

|

|

Reuptake inhibitors |

|

|

SERT

|

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): Alaproclate • Citalopram • Dapoxetine • Desmethylcitalopram • Desmethylsertraline • Escitalopram • Femoxetine • Fluoxetine • Fluvoxamine • Indalpine • Ifoxetine • Litoxetine • Lu AA21004 • Lubazodone • Panuramine • Paroxetine • Pirandamine • RTI-353 • Seproxetine • Sertraline • Vilazodone • Zimelidine; Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs): Bicifadine • Desvenlafaxine • Duloxetine • Eclanamine • Levomilnacipran • Milnacipran • Sibutramine • Venlafaxine; Serotonin-norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors (SNDRIs): Brasofensine • Diclofensine • DOV-102,677 • DOV-21,947 • DOV-216,303 • NS-2359 • SEP-225,289 • SEP-227,162 • Tesofensine; Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs): Amitriptyline • Butriptyline • Cianopramine • Clomipramine • Desipramine • Dosulepin • Doxepin • Imipramine • Lofepramine • Nortriptyline • Pipofezine • Protriptyline • Trimipramine; Tetracyclic antidepressants (TeCAs): Amoxapine; Piperazines: Nefazodone • Trazodone; Antihistamines: Brompheniramine • Chlorpheniramine • Diphenhydramine • Mepyramine/Pyrilamine • Pheniramine • Tripelennamine; Opioids: Meperidine (Pethidine) • Methadone • Propoxyphene; Others: Cocaine • CP-39,332 • Cyclobenzaprine • Dextromethorphan • Dextrorphan • EXP-561 • Fezolamine • Mesembrine • Nefopam • PIM-35 • Pridefrine • Roxindole • SB-649,915 • Ziprasidone

|

|

|

VMAT

|

|

|

|

|

|

Releasing agents |

|

Aminoindanes: 5-IAI • ETAI • MDAI • MDMAI • MMAI • TAI; Aminotetralins: 6-CAT • 8-OH-DPAT • MDAT • MDMAT; Oxazolines: 4-Methylaminorex • Aminorex • Clominorex • Fluminorex; Phenethylamines (also Amphetamines, Cathinones, Phentermines, etc): 2-Methyl-MDA • 4-CAB • 4-FA • 4-FMA • 4-HA • 4-MTA • 5-APDB • 5-Methyl-MDA • 6-APDB • 6-Methyl-MDA • Amiflamine • BDB • BOH • Brephedrone • Butylone • Chlorphentermine • Cloforex • Diethylcathinone • Dimethylcathinone • DMA • DMMA • EBDB • EDMA • Ethylone • Etolorex • Fenfluramine (Dexfenfluramine) • Flephedrone • IAP • IMP • Lophophine • MBDB • MDA • MDEA • MDHMA • MDMA • MDMPEA • MDOH • MDPEA • Mephedrone • Methedrone • Methylone • MMA • MMDA • MMDMA • NAP • Norfenfluramine • pBA • pCA • pIA • PMA • PMEA • PMMA • TAP; Piperazines: 2C-B-BZP • BZP • MBZP • mCPP • MDBZP • MeOPP • Mepiprazole • pFPP • TFMPP; Tryptamines: 4-Methyl-αET • 4-Methyl-αMT • 5-CT • 5-MeO-αET • 5-MeO-αMT • 5-MT • αET • αMT • DMT • Tryptamine (itself); Others: Indeloxazine • Tramadol • Viqualine

|

|

|

|

Enzyme inhibitors |

|

|

|

|

TPH

|

AGN-2979 • Fenclonine

|

|

|

AAAD

|

Benserazide • Carbidopa • Genistein • Methyldopa

|

|

|

|

|

|

MAO

|

Nonselective: Benmoxin • Caroxazone • Echinopsidine • Furazolidone • Hydralazine • Indantadol • Iproclozide • Iproniazid • Isocarboxazid • Isoniazid • Linezolid • Mebanazine • Metfendrazine • Nialamide • Octamoxin • Paraxazone • Phenelzine • Pheniprazine • Phenoxypropazine • Pivalylbenzhydrazine • Procarbazine • Safrazine • Tranylcypromine; MAO-A Selective: Amiflamine • Bazinaprine • Befloxatone • Befol • Brofaromine • Cimoxatone • Clorgiline • Esuprone • Harmala alkaloids (Harmine, Harmaline, Tetrahydroharmine, Harman, Norharman, etc) • Methylene Blue • Metralindole • Minaprine • Moclobemide • Pirlindole • Sercloremine • Tetrindole • Toloxatone • Tyrima

|

|

|

|

|

|

Others |

|

|

Precursors

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Others

|

Activity enhancers: BPAP • PPAP; Reuptake enhancers: Tianeptine

|

|

|

|