Protein

This article is part of the series on: Gene expression |

|||

| Introduction to Genetics | |||

| General flow: DNA > RNA > Protein | |||

| special transfers (RNA > RNA, RNA > DNA, Protein > Protein) |

|||

| Genetic code | |||

| Transcription | |||

| Transcription (Transcription factors, RNA Polymerase,promoter) Prokaryotic / Archaeal / Eukaryotic |

|||

| post-transcriptional modification (hnRNA,5' capping,Splicing,Polyadenylation) |

|||

| Translation | |||

| Translation (Ribosome,tRNA)

Prokaryotic / Archaeal / Eukaryotic |

|||

| post-translational modification (functional groups, peptides, structural changes) |

|||

| gene regulation | |||

| epigenetic regulation (Genomic imprinting) |

|||

| transcriptional regulation | |||

| post-transcriptional regulation (sequestration, alternative splicing,miRNA) |

|||

| translational regulation | |||

| post-translational regulation (reversible,irreversible) |

|||

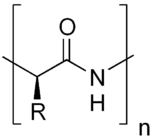

Proteins (also known as polypeptides) are organic compounds made of amino acids arranged in a linear chain and folded into a globular form. The amino acids in a polymer are joined together by the peptide bonds between the carboxyl and amino groups of adjacent amino acid residues. The sequence of amino acids in a protein is defined by the sequence of a gene, which is encoded in the genetic code.[1] In general, the genetic code specifies 20 standard amino acids; however, in certain organisms the genetic code can include selenocysteine—and in certain archaea—pyrrolysine. Shortly after or even during synthesis, the residues in a protein are often chemically modified by post-translational modification, which alters the physical and chemical properties, folding, stability, activity, and ultimately, the function of the proteins. Proteins can also work together to achieve a particular function, and they often associate to form stable complexes.[2]

Of the most distinguishing features of polypeptides is their ability to fold into a globual state, or "structure". The extent to which proteins fold into a defined structure varies widely. Data supports that some protein structures fold into a highly rigid structure with small fluctuations and are therefore considered to be single structure. Other proteins have been shown to undergo large rearrangements from one conformation to another. This conformational change is often associated with a signaling event. Thus, the structure of a protein serves a a medium through which to regulate either the function of a protein or activity of an enzyme. Not all proteins requiring a folding process in order to function as some function in an unfolded state.

Like other biological macromolecules such as polysaccharides and nucleic acids, proteins are essential parts of organisms and participate in virtually every process within cells. Many proteins are enzymes that catalyze biochemical reactions and are vital to metabolism. Proteins also have structural or mechanical functions, such as actin and myosin in muscle and the proteins in the cytoskeleton, which form a system of scaffolding that maintains cell shape. Other proteins are important in cell signaling, immune responses, cell adhesion, and the cell cycle. Proteins are also necessary in animals' diets, since animals cannot synthesize all the amino acids they need and must obtain essential amino acids from food. Through the process of digestion, animals break down ingested protein into free amino acids that are then used in metabolism.

Proteins were first described by the Dutch chemist Gerhardus Johannes Mulder and named by the Swedish chemist Jöns Jakob Berzelius in 1838. Early nutritional scientists such as the German Carl von Voit believed that protein was the most important nutrient for maintaining the structure of the body, because it was generally believed that "flesh makes flesh."[3] The central role of proteins as enzymes in living organisms was however not fully appreciated until 1926, when James B. Sumner showed that the enzyme urease was in fact a protein.[4] The first protein to be sequenced was insulin, by Frederick Sanger, who won the Nobel Prize for this achievement in 1958. The first protein structures to be solved were hemoglobin and myoglobin, by Max Perutz and Sir John Cowdery Kendrew, respectively, in 1958.[5][6] The three-dimensional structures of both proteins were first determined by x-ray diffraction analysis; Perutz and Kendrew shared the 1962 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for these discoveries. Proteins may be purified from other cellular components using a variety of techniques such as ultracentrifugation, precipitation, electrophoresis, and chromatography; the advent of genetic engineering has made possible a number of methods to facilitate purification. Methods commonly used to study protein structure and function include immunohistochemistry, site-directed mutagenesis, nuclear magnetic resonance and mass spectrometry.

Contents |

Biochemistry

Most proteins are linear polymers built from series of up to 20 different L-α-amino acids. All amino acids possess common structural features, including an α-carbon to which an amino group, a carboxyl group, and a variable side chain are bonded. Only proline differs from this basic structure as it contains an unusual ring to the N-end amine group, which forces the CO–NH amide moiety into a fixed conformation.[7] The side chains of the standard amino acids, detailed in the list of standard amino acids, have a great variety of chemical structures and properties; it is the combined effect of all of the amino acid side chains in a protein that ultimately determines its three-dimensional structure and its chemical reactivity.[8]

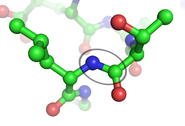

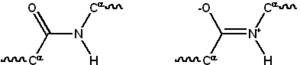

The amino acids in a polypeptide chain are linked by peptide bonds. Once linked in the protein chain, an individual amino acid is called a residue, and the linked series of carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen atoms are known as the main chain or protein backbone.[9] The peptide bond has two resonance forms that contribute some double-bond character and inhibit rotation around its axis, so that the alpha carbons are roughly coplanar. The other two dihedral angles in the peptide bond determine the local shape assumed by the protein backbone.[10] The end of the protein with a free carboxyl group is known as the C-terminus or carboxy terminus, whereas the end with a free amino group is known as the N-terminus or amino terminus.

The words protein, polypeptide, and peptide are a little ambiguous and can overlap in meaning. Protein is generally used to refer to the complete biological molecule in a stable conformation, whereas peptide is generally reserved for a short amino acid oligomers often lacking a stable three-dimensional structure. However, the boundary between the two is not well defined and usually lies near 20–30 residues.[11] Polypeptide can refer to any single linear chain of amino acids, usually regardless of length, but often implies an absence of a defined conformation.

Synthesis

Proteins are assembled from amino acids using information encoded in genes. Each protein has its own unique amino acid sequence that is specified by the nucleotide sequence of the gene encoding this protein. The genetic code is a set of three-nucleotide sets called codons and each three-nucleotide combination designates an amino acid, for example AUG (adenine-uracil-guanine) is the code for methionine. Because DNA contains four nucleotides, the total number of possible codons is 64; hence, there is some redundancy in the genetic code, with some amino acids specified by more than one codon.[12] Genes encoded in DNA are first transcribed into pre-messenger RNA (mRNA) by proteins such as RNA polymerase. Most organisms then process the pre-mRNA (also known as a primary transcript) using various forms of post-transcriptional modification to form the mature mRNA, which is then used as a template for protein synthesis by the ribosome. In prokaryotes the mRNA may either be used as soon as it is produced, or be bound by a ribosome after having moved away from the nucleoid. In contrast, eukaryotes make mRNA in the cell nucleus and then translocate it across the nuclear membrane into the cytoplasm, where protein synthesis then takes place. The rate of protein synthesis is higher in prokaryotes than eukaryotes and can reach up to 20 amino acids per second.[13]

The process of synthesizing a protein from an mRNA template is known as translation. The mRNA is loaded onto the ribosome and is read three nucleotides at a time by matching each codon to its base pairing anticodon located on a transfer RNA molecule, which carries the amino acid corresponding to the codon it recognizes. The enzyme aminoacyl tRNA synthetase "charges" the tRNA molecules with the correct amino acids. The growing polypeptide is often termed the nascent chain. Proteins are always biosynthesized from N-terminus to C-terminus.[12]

The size of a synthesized protein can be measured by the number of amino acids it contains and by its total molecular mass, which is normally reported in units of daltons (synonymous with atomic mass units), or the derivative unit kilodalton (kDa). Yeast proteins are on average 466 amino acids long and 53 kDa in mass.[11] The largest known proteins are the titins, a component of the muscle sarcomere, with a molecular mass of almost 3,000 kDa and a total length of almost 27,000 amino acids.[14]

Chemical synthesis

Short proteins can also be synthesized chemically by a family of methods known as peptide synthesis, which rely on organic synthesis techniques such as chemical ligation to produce peptides in high yield.[15] Chemical synthesis allows for the introduction of non-natural amino acids into polypeptide chains, such as attachment of fluorescent probes to amino acid side chains.[16] These methods are useful in laboratory biochemistry and cell biology, though generally not for commercial applications. Chemical synthesis is inefficient for polypeptides longer than about 300 amino acids, and the synthesized proteins may not readily assume their native tertiary structure. Most chemical synthesis methods proceed from C-terminus to N-terminus, opposite the biological reaction.[17]

Structure of proteins

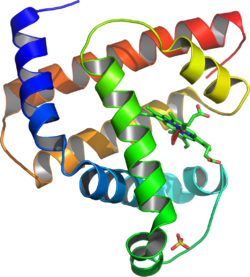

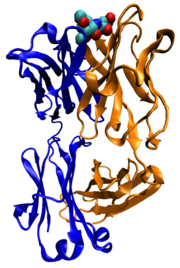

Most proteins fold into unique 3-dimensional structures. The shape into which a protein naturally folds is known as its native conformation.[18] Although many proteins can fold unassisted, simply through the chemical properties of their amino acids, others require the aid of molecular chaperones to fold into their native states.[19] Biochemists often refer to four distinct aspects of a protein's structure:[20]

- Primary structure: the amino acid sequence.

- Secondary structure: regularly repeating local structures stabilized by hydrogen bonds. The most common examples are the alpha helix, beta sheet and turns. Because secondary structures are local, many regions of different secondary structure can be present in the same protein molecule.

- Tertiary structure: the overall shape of a single protein molecule; the spatial relationship of the secondary structures to one another. Tertiary structure is generally stabilized by nonlocal interactions, most commonly the formation of a hydrophobic core, but also through salt bridges, hydrogen bonds, disulfide bonds, and even post-translational modifications. The term "tertiary structure" is often used as synonymous with the term fold. The tertiary structure is what controls the basic function of the protein.

- Quaternary structure: the structure formed by several protein molecules (polypeptide chains), usually called protein subunits in this context, which function as a single protein complex.

Proteins are not entirely rigid molecules. In addition to these levels of structure, proteins may shift between several related structures while they perform their functions. In the context of these functional rearrangements, these tertiary or quaternary structures are usually referred to as "conformations", and transitions between them are called conformational changes. Such changes are often induced by the binding of a substrate molecule to an enzyme's active site, or the physical region of the protein that participates in chemical catalysis. In solution proteins also undergo variation in structure through thermal vibration and the collision with other molecules.[21]

Proteins can be informally divided into three main classes, which correlate with typical tertiary structures: globular proteins, fibrous proteins, and membrane proteins. Almost all globular proteins are soluble and many are enzymes. Fibrous proteins are often structural, such as collagen, the major component of connective tissue, or keratin, the protein component of hair and nails. Membrane proteins often serve as receptors or provide channels for polar or charged molecules to pass through the cell membrane.[22]

A special case of intramolecular hydrogen bonds within proteins, poorly shielded from water attack and hence promoting their own dehydration, are called dehydrons.[23]

Structure determination

Discovering the tertiary structure of a protein, or the quaternary structure of its complexes, can provide important clues about how the protein performs its function. Common experimental methods of structure determination include X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy, both of which can produce information at atomic resolution. However, NMR experiments are able to provide information from which a subset of distances between pairs of atoms can be estimated, and the final possible conformations for a protein are determined by solving a distance geometry problem. Dual polarisation interferometry is a quantitative analytical method for measuring the overall protein conformation and conformational changes due to interactions or other stimulus. Circular dichroism is another laboratory technique for determining internal beta sheet/ helical composition of proteins. Cryoelectron microscopy is used to produce lower-resolution structural information about very large protein complexes, including assembled viruses;[24] a variant known as electron crystallography can also produce high-resolution information in some cases , especially for two-dimensional crystals of membrane proteins.[25] Solved structures are usually deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB), a freely available resource from which structural data about thousands of proteins can be obtained in the form of Cartesian coordinates for each atom in the protein.[26]

Many more gene sequences are known than protein structures. Further, the set of solved structures is biased toward proteins that can be easily subjected to the conditions required in X-ray crystallography, one of the major structure determination methods. In particular, globular proteins are comparatively easy to crystallize in preparation for X-ray crystallography. Membrane proteins, by contrast, are difficult to crystallize and are underrepresented in the PDB.[27] Structural genomics initiatives have attempted to remedy these deficiencies by systematically solving representative structures of major fold classes. Protein structure prediction methods attempt to provide a means of generating a plausible structure for proteins whose structures have not been experimentally determined.

Cellular functions

Proteins are the chief actors within the cell, said to be carrying out the duties specified by the information encoded in genes.[11] With the exception of certain types of RNA, most other biological molecules are relatively inert elements upon which proteins act. Proteins make up half the dry weight of an Escherichia coli cell, whereas other macromolecules such as DNA and RNA make up only 3% and 20%, respectively.[28] The set of proteins expressed in a particular cell or cell type is known as its proteome.

The chief characteristic of proteins that also allows their diverse set of functions is their ability to bind other molecules specifically and tightly. The region of the protein responsible for binding another molecule is known as the binding site and is often a depression or "pocket" on the molecular surface. This binding ability is mediated by the tertiary structure of the protein, which defines the binding site pocket, and by the chemical properties of the surrounding amino acids' side chains. Protein binding can be extraordinarily tight and specific; for example, the ribonuclease inhibitor protein binds to human angiogenin with a sub-femtomolar dissociation constant (<10−15 M) but does not bind at all to its amphibian homolog onconase (>1 M). Extremely minor chemical changes such as the addition of a single methyl group to a binding partner can sometimes suffice to nearly eliminate binding; for example, the aminoacyl tRNA synthetase specific to the amino acid valine discriminates against the very similar side chain of the amino acid isoleucine.[29]

Proteins can bind to other proteins as well as to small-molecule substrates. When proteins bind specifically to other copies of the same molecule, they can oligomerize to form fibrils; this process occurs often in structural proteins that consist of globular monomers that self-associate to form rigid fibers. Protein–protein interactions also regulate enzymatic activity, control progression through the cell cycle, and allow the assembly of large protein complexes that carry out many closely related reactions with a common biological function. Proteins can also bind to, or even be integrated into, cell membranes. The ability of binding partners to induce conformational changes in proteins allows the construction of enormously complex signaling networks.[30] Importantly, as interactions between proteins are reversible, and depend heavily on the availability of different groups of partner proteins to form aggregates that are capable to carry out discrete sets of function, study of the interactions between specific proteins is a key to understand important aspects of cellular function, and ultimately the properties that distinguish particular cell types.[31][32]

Enzymes

The best-known role of proteins in the cell is as enzymes, which catalyze chemical reactions. Enzymes are usually highly specific and accelerate only one or a few chemical reactions. Enzymes carry out most of the reactions involved in metabolism, as well as manipulating DNA in processes such as DNA replication, DNA repair, and transcription. Some enzymes act on other proteins to add or remove chemical groups in a process known as post-translational modification. About 4,000 reactions are known to be catalyzed by enzymes.[33] The rate acceleration conferred by enzymatic catalysis is often enormous — as much as 1017-fold increase in rate over the uncatalyzed reaction in the case of orotate decarboxylase (78 million years without the enzyme, 18 milliseconds with the enzyme).[34]

The molecules bound and acted upon by enzymes are called substrates. Although enzymes can consist of hundreds of amino acids, it is usually only a small fraction of the residues that come in contact with the substrate, and an even smaller fraction — 3 to 4 residues on average — that are directly involved in catalysis.[35] The region of the enzyme that binds the substrate and contains the catalytic residues is known as the active site.

Cell signaling and ligand binding

Many proteins are involved in the process of cell signaling and signal transduction. Some proteins, such as insulin, are extracellular proteins that transmit a signal from the cell in which they were synthesized to other cells in distant tissues. Others are membrane proteins that act as receptors whose main function is to bind a signaling molecule and induce a biochemical response in the cell. Many receptors have a binding site exposed on the cell surface and an effector domain within the cell, which may have enzymatic activity or may undergo a conformational change detected by other proteins within the cell.[36]

Antibodies are protein components of adaptive immune system whose main function is to bind antigens, or foreign substances in the body, and target them for destruction. Antibodies can be secreted into the extracellular environment or anchored in the membranes of specialized B cells known as plasma cells. Whereas enzymes are limited in their binding affinity for their substrates by the necessity of conducting their reaction, antibodies have no such constraints. An antibody's binding affinity to its target is extraordinarily high.[37]

Many ligand transport proteins bind particular small biomolecules and transport them to other locations in the body of a multicellular organism. These proteins must have a high binding affinity when their ligand is present in high concentrations, but must also release the ligand when it is present at low concentrations in the target tissues. The canonical example of a ligand-binding protein is haemoglobin, which transports oxygen from the lungs to other organs and tissues in all vertebrates and has close homologs in every biological kingdom.[38] Lectins are sugar-binding proteins which are highly specific for their sugar moieties. Lectins typically play a role in biological recognition phenomena involving cells and proteins.[39] Receptors and hormones are highly specific binding proteins.

Transmembrane proteins can also serve as ligand transport proteins that alter the permeability of the cell membrane to small molecules and ions. The membrane alone has a hydrophobic core through which polar or charged molecules cannot diffuse. Membrane proteins contain internal channels that allow such molecules to enter and exit the cell. Many ion channel proteins are specialized to select for only a particular ion; for example, potassium and sodium channels often discriminate for only one of the two ions.[40]

Structural proteins

Structural proteins confer stiffness and rigidity to otherwise-fluid biological components. Most structural proteins are fibrous proteins; for example, actin and tubulin are globular and soluble as monomers, but polymerize to form long, stiff fibers that comprise the cytoskeleton, which allows the cell to maintain its shape and size. Collagen and elastin are critical components of connective tissue such as cartilage, and keratin is found in hard or filamentous structures such as hair, nails, feathers, hooves, and some animal shells.[41]

Other proteins that serve structural functions are motor proteins such as myosin, kinesin, and dynein, which are capable of generating mechanical forces. These proteins are crucial for cellular motility of single celled organisms and the sperm of many multicellular organisms which reproduce sexually. They also generate the forces exerted by contracting muscles.[42]

Methods of study

As some of the most commonly studied biological molecules, the activities and structures of proteins are examined both in vitro and in vivo. In vitro studies of purified proteins in controlled environments are useful for learning how a protein carries out its function: for example, enzyme kinetics studies explore the chemical mechanism of an enzyme's catalytic activity and its relative affinity for various possible substrate molecules. By contrast, in vivo experiments on proteins' activities within cells or even within whole organisms can provide complementary information about where a protein functions and how it is regulated.

Protein purification

In order to perform in vitro analysis, a protein must be purified away from other cellular components. This process usually begins with cell lysis, in which a cell's membrane is disrupted and its internal contents released into a solution known as a crude lysate. The resulting mixture can be purified using ultracentrifugation, which fractionates the various cellular components into fractions containing soluble proteins; membrane lipids and proteins; cellular organelles, and nucleic acids. Precipitation by a method known as salting out can concentrate the proteins from this lysate. Various types of chromatography are then used to isolate the protein or proteins of interest based on properties such as molecular weight, net charge and binding affinity.[43] The level of purification can be monitored using various types of gel electrophoresis if the desired protein's molecular weight and isoelectric point are known, by spectroscopy if the protein has distinguishable spectroscopic features, or by enzyme assays if the protein has enzymatic activity. Additionally, proteins can be isolated according their charge using electrofocusing.[44]

For natural proteins, a series of purification steps may be necessary to obtain protein sufficiently pure for laboratory applications. To simplify this process, genetic engineering is often used to add chemical features to proteins that make them easier to purify without affecting their structure or activity. Here, a "tag" consisting of a specific amino acid sequence, often a series of histidine residues (a "His-tag"), is attached to one terminus of the protein. As a result, when the lysate is passed over a chromatography column containing nickel, the histidine residues ligate the nickel and attach to the column while the untagged components of the lysate pass unimpeded. A number of different tags have been developed to help researchers purify specific proteins from complex mixtures.[45]

Cellular localization

The study of proteins in vivo is often concerned with the synthesis and localization of the protein within the cell. Although many intracellular proteins are synthesized in the cytoplasm and membrane-bound or secreted proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum, the specifics of how proteins are targeted to specific organelles or cellular structures is often unclear. A useful technique for assessing cellular localization uses genetic engineering to express in a cell a fusion protein or chimera consisting of the natural protein of interest linked to a "reporter" such as green fluorescent protein (GFP).[46] The fused protein's position within the cell can be cleanly and efficiently visualized using microscopy,[47] as shown in the figure opposite.

Other methods for elucidating the cellular location of proteins requires the use of known compartmental markers for regions such as the ER, the Golgi, lysosomes/vacuoles, mitochondria, chloroplasts, plasma membrane, etc. With the use of fluorescently tagged versions of these markers or of antibodies to known markers, it becomes much simpler to identify the localization of a protein of interest. For example, indirect immunofluorescence will allow for fluorescence colocalization and demonstration of location. Fluorescent dyes are used to label cellular compartments for a similar purpose.[48]

Other possibilities exist, as well. For example, immunohistochemistry usually utilizes an antibody to one or more proteins of interest that are conjugated to enzymes yielding either luminescent or chromogenic signals that can be compared between samples, allowing for localization information. Another applicable technique is cofractionation in sucrose (or other material) gradients using isopycnic centrifugation.[49] While this technique does not prove colocalization of a compartment of known density and the protein of interest, it does increase the likelihood, and is more amenable to large-scale studies.

Finally, the gold-standard method of cellular localization is immunoelectron microscopy. This technique also uses an antibody to the protein of interest, along with classical electron microscopy techniques. The sample is prepared for normal electron microscopic examination, and then treated with an antibody to the protein of interest that is conjugated to an extremely electro-dense material, usually gold. This allows for the localization of both ultrastructural details as well as the protein of interest.[50]

Through another genetic engineering application known as site-directed mutagenesis, researchers can alter the protein sequence and hence its structure, cellular localization, and susceptibility to regulation. This technique even allows the incorporation of unnatural amino acids into proteins, using modified tRNAs,[51] and may allow the rational design of new proteins with novel properties.[52]

Proteomics and bioinformatics

The total complement of proteins present at a time in a cell or cell type is known as its proteome, and the study of such large-scale data sets defines the field of proteomics, named by analogy to the related field of genomics. Key experimental techniques in proteomics include 2D electrophoresis,[53] which allows the separation of a large number of proteins, mass spectrometry,[54] which allows rapid high-throughput identification of proteins and sequencing of peptides (most often after in-gel digestion), protein microarrays,[55] which allow the detection of the relative levels of a large number of proteins present in a cell, and two-hybrid screening, which allows the systematic exploration of protein–protein interactions.[56] The total complement of biologically possible such interactions is known as the interactome.[57] A systematic attempt to determine the structures of proteins representing every possible fold is known as structural genomics.[58]

The large amount of genomic and proteomic data available for a variety of organisms, including the human genome, allows researchers to efficiently identify homologous proteins in distantly related organisms by sequence alignment. Sequence profiling tools can perform more specific sequence manipulations such as restriction enzyme maps, open reading frame analyses for nucleotide sequences, and secondary structure prediction. From this data phylogenetic trees can be constructed and evolutionary hypotheses developed using special software like ClustalW regarding the ancestry of modern organisms and the genes they express. The field of bioinformatics seeks to assemble, annotate, and analyze genomic and proteomic data, applying computational techniques to biological problems such as gene finding and cladistics.

Structure prediction and simulation

Complementary to the field of structural genomics, protein structure prediction seeks to develop efficient ways to provide plausible models for proteins whose structures have not yet been determined experimentally.[59] The most successful type of structure prediction, known as homology modeling, relies on the existence of a "template" structure with sequence similarity to the protein being modeled; structural genomics' goal is to provide sufficient representation in solved structures to model most of those that remain.[60] Although producing accurate models remains a challenge when only distantly related template structures are available, it has been suggested that sequence alignment is the bottleneck in this process, as quite accurate models can be produced if a "perfect" sequence alignment is known.[61] Many structure prediction methods have served to inform the emerging field of protein engineering, in which novel protein folds have already been designed.[62] A more complex computational problem is the prediction of intermolecular interactions, such as in molecular docking and protein–protein interaction prediction.[63]

The processes of protein folding and binding can be simulated using such technique as molecular mechanics, in particular, molecular dynamics and Monte Carlo, which increasingly take advantage of parallel and distributed computing (Folding@Home project;[64] molecular modeling on GPU). The folding of small alpha-helical protein domains such as the villin headpiece[65] and the HIV accessory protein[66] have been successfully simulated in silico, and hybrid methods that combine standard molecular dynamics with quantum mechanics calculations have allowed exploration of the electronic states of rhodopsins.[67]

Nutrition

Most microorganisms and plants can biosynthesize all 20 standard amino acids, while animals (including humans) must obtain some of the amino acids from the diet.[28] The amino acids that an organism cannot synthesize on its own are referred to as essential amino acids. Key enzymes that synthesize certain amino acids are not present in animals — such as aspartokinase, which catalyzes the first step in the synthesis of lysine, methionine, and threonine from aspartate. If amino acids are present in the environment, microorganisms can conserve energy by taking up the amino acids from their surroundings and downregulating their biosynthetic pathways.

In animals, amino acids are obtained through the consumption of foods containing protein. Ingested proteins are then broken down into amino acids through digestion, which typically involves denaturation of the protein through exposure to acid and hydrolysis by enzymes called proteases. Some ingested amino acids are used for protein biosynthesis, while others are converted to glucose through gluconeogenesis, or fed into the citric acid cycle. This use of protein as a fuel is particularly important under starvation conditions as it allows the body's own proteins to be used to support life, particularly those found in muscle.[68] Amino acids are also an important dietary source of nitrogen.

History and etymology

Proteins were recognized as a distinct class of biological molecules in the eighteenth century by Antoine Fourcroy and others, distinguished by the molecules' ability to coagulate or flocculate under treatments with heat or acid. Noted examples at the time included albumin from egg whites, blood serum albumin, fibrin, and wheat gluten. Dutch chemist Gerhardus Johannes Mulder carried out elemental analysis of common proteins and found that nearly all proteins had the same empirical formula, C400H620N100O120P1S1.[69] He came to the erroneous conclusion that they might be composed of a single type of (very large) molecule. The term "protein" to describe these molecules was proposed in 1838 by Mulder's associate Jöns Jakob Berzelius; protein is derived from the Greek word πρωτεῖος (proteios), meaning "primary",[70] "in the lead", or "standing in front".[71] Mulder went on to identify the products of protein degradation such as the amino acid leucine for which he found a (nearly correct) molecular weight of 131 Da.[69]

The difficulty in purifying proteins in large quantities made them very difficult for early protein biochemists to study. Hence, early studies focused on proteins that could be purified in large quantities, e.g., those of blood, egg white, various toxins, and digestive/metabolic enzymes obtained from slaughterhouses. In the 1950s, the Armour Hot Dog Co. purified 1 kg of pure bovine pancreatic ribonuclease A and made it freely available to scientists; this gesture helped ribonuclease A become a major target for biochemical study for the following decades.[69]

Linus Pauling is credited with the successful prediction of regular protein secondary structures based on hydrogen bonding, an idea first put forth by William Astbury in 1933.[72] Later work by Walter Kauzmann on denaturation,[73][74] based partly on previous studies by Kaj Linderstrøm-Lang,[75] contributed an understanding of protein folding and structure mediated by hydrophobic interactions. In 1949 Fred Sanger correctly determined the amino acid sequence of insulin, thus conclusively demonstrating that proteins consisted of linear polymers of amino acids rather than branched chains, colloids, or cyclols.[76] The first atomic-resolution structures of proteins were solved by X-ray crystallography in the 1960s[77] and by NMR in the 1980s.[77] As of 2009, the Protein Data Bank has over 55,000 atomic-resolution structures of proteins.[78] In more recent times, cryo-electron microscopy of large macromolecular assemblies[79] and computational protein structure prediction of small protein domains[80] are two methods approaching atomic resolution.

See also

- Expression cloning

- Intein

- List of proteins

- List of recombinant proteins

- Prion

- Protein design

- Protein dynamics

- Protein structure prediction software

- Proteopathy

- Proteopedia

- Cdx protein family

- NUN buffer

Footnotes

- ↑ Ridley, M. (2006). Genome. New York, NY: Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-019497-9

- ↑ Maton A, Hopkins J, McLaughlin CW, Johnson S, Warner MQ, LaHart D, Wright JD (1993). Human Biology and Health. Englewood Cliffs, Michigan, USA: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-981176-1. OCLC 32308337.

- ↑ Bischoff, TLW & Voit, C (1860). Die Gesetze der Ernaehrung des Pflanzenfressers durch neue Untersuchungen festgestellt. Leipzig, Heidelberg.

- ↑ Sumner, JB (1926). "The isolation and crystallization of the enzyme urease. Preliminary paper". Journal of Biological Chemistry 69: 435–41. http://www.jbc.org/cgi/reprint/69/2/435.pdf?ijkey=028d5e540dab50accbf86e01be08db51ef49008f.

- ↑ Muirhead H, Perutz M (1963). "Structure of hemoglobin. A three-dimensional fourier synthesis of reduced human hemoglobin at 5.5 Å resolution". Nature 199 (4894): 633–38. doi:10.1038/199633a0. PMID 14074546.

- ↑ Kendrew J, Bodo G, Dintzis H, Parrish R, Wyckoff H, Phillips D (1958). "A three-dimensional model of the myoglobin molecule obtained by x-ray analysis". Nature 181 (4610): 662–66. doi:10.1038/181662a0. PMID 13517261.

- ↑ Nelson DL, Cox MM. (2005). Lehninger's Principles of Biochemistry, 4th Edition. W. H. Freeman and Company, New York.

- ↑ Gutteridge A, Thornton JM (2005). "Understanding nature's catalytic toolkit". Trends in Biochemical Sciences 30 (11): 622–29. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2005.09.006. PMID 16214343.

- ↑ Murray et al., p. 19.

- ↑ Murray et al., p. 31.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Lodish H, Berk A, Matsudaira P, Kaiser CA, Krieger M, Scott MP, Zipurksy SL, Darnell J. (2004). Molecular Cell Biology 5th ed. WH Freeman and Company: New York, NY.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 van Holde and Mathews, pp. 1002–42.

- ↑ Dobson CM (2000). "The nature and significance of protein folding". In Pain RH. (ed.). Mechanisms of Protein Folding. Oxford, Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-963789-X.

- ↑ Fulton A, Isaacs W (1991). "Titin, a huge, elastic sarcomeric protein with a probable role in morphogenesis". Bioessays 13 (4): 157–61. doi:10.1002/bies.950130403. PMID 1859393.

- ↑ Bruckdorfer T, Marder O, Albericio F (2004). "From production of peptides in milligram amounts for research to multi-tons quantities for drugs of the future". Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology 5 (1): 29–43. doi:10.2174/1389201043489620. PMID 14965208.

- ↑ Schwarzer D, Cole P (2005). "Protein semisynthesis and expressed protein ligation: chasing a protein's tail". Current Opinions in Chemical Biology 9 (6): 561–69. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.09.018. PMID 16226484.

- ↑ Kent SB (2009). "Total chemical synthesis of proteins". Chemical Society Reviews 38 (2): 338–51. doi:10.1039/b700141j. PMID 19169452.

- ↑ Murray et al., p. 36.

- ↑ Murray et al., p. 37.

- ↑ Murray et al., pp. 30–34.

- ↑ van Holde and Mathews, pp. 368–75.

- ↑ van Holde and Mathews, pp. 165–85.

- ↑ Fernández A, Scott R (2003). "Dehydron: a structurally encoded signal for protein interaction". Biophysical Journal 85 (3): 1914–28. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74619-0. PMID 12944304. PMC 1303363. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0006-3495(03)74619-0.

- ↑ Branden and Tooze, pp. 340–41.

- ↑ Gonen T, Cheng Y, Sliz P, Hiroaki Y, Fujiyoshi Y, Harrison SC, Walz T (2005). "Lipid-protein interactions in double-layered two-dimensional AQP0 crystals". Nature 438 (7068): 633–38. doi:10.1038/nature04321. PMID 16319884.

- ↑ Standley DM, Kinjo AR, Kinoshita K, Nakamura H (2008). "Protein structure databases with new web services for structural biology and biomedical research". Briefings in Bioinformatics 9 (4): 276–85. doi:10.1093/bib/bbn015. PMID 18430752. http://bib.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=18430752.

- ↑ Walian P, Cross TA, Jap BK (2004). "Structural genomics of membrane proteins". Genome Biology 5 (4): 215. doi:10.1186/gb-2004-5-4-215. PMID 15059248. PMC 395774. http://genomebiology.com/1465-6906/5/215. Retrieved 2009-04-14.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Voet D, Voet JG. (2004). Biochemistry Vol 1 3rd ed. Wiley: Hoboken, NJ.

- ↑ Sankaranarayanan R, Moras D (2001). "The fidelity of the translation of the genetic code". Acta Biochimica Polonica 48 (2): 323–35. PMID 11732604.

- ↑ van Holde and Mathews, pp. 830–49.

- ↑ Copland JA, Sheffield-Moore M, Koldzic-Zivanovic N, Gentry S, Lamprou G, Tzortzatou-Stathopoulou F, Zoumpourlis V, Urban RJ, Vlahopoulos SA. Sex steroid receptors in skeletal differentiation and epithelial neoplasia: is tissue-specific intervention possible? Bioessays. 2009 Jun;31(6):629–641.PMID: 19382224

- ↑ Samarin S, Nusrat A. Regulation of epithelial apical junctional complex by Rho family GTPases. Front Biosci. 2009 Jan 1;14:1129–42. Review. PMID: 19273120

- ↑ Bairoch A (2000). "The ENZYME database in 2000". Nucleic Acids Research 28 (1): 304–305. doi:10.1093/nar/28.1.304. PMID 10592255. PMC 102465. http://www.expasy.org/NAR/enz00.pdf.

- ↑ Radzicka A, Wolfenden R (1995). "A proficient enzyme". Science 6 (267): 90–93. doi:10.1126/science.7809611. PMID 7809611.

- ↑ EBI External Servces (2010-01-20). "The Catalytic Site Atlas at The European Bioinformatics Institute". Ebi.ac.uk. http://www.ebi.ac.uk/thornton-srv/databases/CSA/. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ Branden and Tooze, pp. 251–281.

- ↑ van Holde and Mathews, pp. 247–50.

- ↑ van Holde and Mathews, pp. 220–29.

- ↑ Rüdiger H, Siebert HC, Solís D, Jiménez-Barbero J, Romero A, von der Lieth CW, Diaz-Mariño T, Gabius HJ (2000). "Medicinal chemistry based on the sugar code: fundamentals of lectinology and experimental strategies with lectins as targets". Current Medicinal Chemistry 7 (4): 389–416. PMID 10702616. http://www.bentham-direct.org/pages/content.php?CMC/2000/00000007/00000004/0002C.SGM.

- ↑ Branden and Tooze, pp. 232–234.

- ↑ van Holde and Mathews, pp. 178–81.

- ↑ van Holde and Mathews, pp. 258–64; 272.

- ↑ Murray et al., pp. 21–24.

- ↑ Hey J, Posch A, Cohen A, Liu N, Harbers A (2008). "Fractionation of complex protein mixtures by liquid-phase isoelectric focusing". Methods in Molecular Biology 424: 225–39. doi:10.1007/978-1-60327-064-9_19. PMID 18369866.

- ↑ Terpe K (2003). "Overview of tag protein fusions: from molecular and biochemical fundamentals to commercial systems". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 60 (5): 523–33. doi:10.1007/s00253-002-1158-6. PMID 12536251.

- ↑ Stepanenko OV, Verkhusha VV, Kuznetsova IM, Uversky VN, Turoverov KK (August 2008). "Fluorescent proteins as biomarkers and biosensors: throwing color lights on molecular and cellular processes". Curr. Protein Pept. Sci 9 (4): 338–69. doi:10.2174/138920308785132668. PMID 18691124.

- ↑ Yuste R (2005). "Fluorescence microscopy today". Nature Methods 2 (12): 902–904. doi:10.1038/nmeth1205-902. PMID 16299474.

- ↑ Margolin W (2000). "Green fluorescent protein as a reporter for macromolecular localization in bacterial cells". Methods (San Diego, Calif.) 20 (1): 62–72. doi:10.1006/meth.1999.0906. PMID 10610805. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1046-2023(99)90906-4.

- ↑ Walker JH, Wilson K (2000). Principles and Techniques of Practical Biochemistry. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 287–89. ISBN 0-521-65873-X.

- ↑ Mayhew TM, Lucocq JM (2008). "Developments in cell biology for quantitative immunoelectron microscopy based on thin sections: a review". Histochemistry and Cell Biology 130 (2): 299–313. doi:10.1007/s00418-008-0451-6. PMID 18553098.

- ↑ Hohsaka T, Sisido M (December 2002). "Incorporation of non-natural amino acids into proteins". Curr Opin Chem Biol 6 (6): 809–15. doi:10.1016/S1367-5931(02)00376-9. PMID 12470735.

- ↑ Cedrone F, Ménez A, Quéméneur E (August 2000). "Tailoring new enzyme functions by rational redesign". Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 10 (4): 405–10. doi:10.1016/S0959-440X(00)00106-8. PMID 10981626.

- ↑ Görg A, Weiss W, Dunn MJ (2004). "Current two-dimensional electrophoresis technology for proteomics". Proteomics 4 (12): 3665–85. doi:10.1002/pmic.200401031. PMID 15543535.

- ↑ Conrotto P, Souchelnytskyi S (2008). "Proteomic approaches in biological and medical sciences: principles and applications". Experimental Oncology 30 (3): 171–80. PMID 18806738. http://www.exp-oncology.com.ua/en/archives/36/699.html.

- ↑ Joos T, Bachmann J (2009). "Protein microarrays: potentials and limitations". Frontiers in Bioscience 14: 4376–85. doi:10.2741/3534. PMID 19273356. http://www.bioscience.org/2009/v14/af/3534/fulltext.htm.

- ↑ Koegl M, Uetz P (2007). "Improving yeast two-hybrid screening systems". Briefings in Functional Genomics & Proteomics 6 (4): 302–12. doi:10.1093/bfgp/elm035. PMID 18218650. http://bfgp.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=18218650.

- ↑ Plewczyński D, Ginalski K (2009). "The interactome: predicting the protein–protein interactions in cells". Cellular & Molecular Biology Letters 14 (1): 1–22. doi:10.2478/s11658-008-0024-7. PMID 18839074.

- ↑ Zhang C, Kim SH (2003). "Overview of structural genomics: from structure to function". Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 7 (1): 28–32. doi:10.1016/S1367-5931(02)00015-7. PMID 12547423. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1367593102000157.

- ↑ Zhang Y (2008). "Progress and challenges in protein structure prediction". Current Opinions in Structural Biology 18 (3): 342–48. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2008.02.004. Entrez Pubmed 18436442. PMID 18436442.

- ↑ Xiang Z (2006). "Advances in homology protein structure modeling". Current Protein and Peptide Science 7 (3): 217–27. doi:10.2174/138920306777452312. PMID 16787261. PMC 1839925. http://www.bentham-direct.org/pages/content.php?CPPS/2006/00000007/00000003/0004K.SGM.

- ↑ Zhang Y, Skolnick J (2005). "The protein structure prediction problem could be solved using the current PDB library". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U.S.A 102 (4): 1029–34. doi:10.1073/pnas.0407152101. PMID 15653774. PMC 545829. http://www.pnas.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15653774.

- ↑ Kuhlman B, Dantas G, Ireton GC, Varani G, Stoddard BL, Baker D (2003). "Design of a novel globular protein fold with atomic-level accuracy". Science 302 (5649): 1364–68. doi:10.1126/science.1089427. PMID 14631033. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=14631033.

- ↑ Ritchie DW (2008). "Recent progress and future directions in protein–protein docking". Current Protein and Peptide Science 9 (1): 1–15. doi:10.2174/138920308783565741. PMID 18336319. http://www.bentham-direct.org/pages/content.php?CPPS/2008/00000009/00000001/0001K.SGM.

- ↑ Scheraga HA, Khalili M, Liwo A (2007). "Protein-folding dynamics: overview of molecular simulation techniques". Annual Review of Physical Chemistry 58: 57–83. doi:10.1146/annurev.physchem.58.032806.104614. PMID 17034338. http://arjournals.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.physchem.58.032806.104614?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- ↑ Zagrovic B, Snow CD, Shirts MR, Pande VS (2002). "Simulation of folding of a small alpha-helical protein in atomistic detail using worldwide-distributed computing". Journal of Molecular Biology 323 (5): 927–37. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00997-X. PMID 12417204. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S002228360200997X. Retrieved 2009-04-14.

- ↑ Herges T, Wenzel W (2005). "In silico folding of a three helix protein and characterization of its free-energy landscape in an all-atom force field". Physical Review Letters 94 (1): 018101. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.018101. PMID 15698135. http://link.aps.org/abstract/PRL/v94/p018101. Retrieved 2009-04-14.

- ↑ Hoffmann M, Wanko M, Strodel P, König PH, Frauenheim T, Schulten K, Thiel W, Tajkhorshid E, Elstner M (2006). "Color tuning in rhodopsins: the mechanism for the spectral shift between bacteriorhodopsin and sensory rhodopsin II". Journal of the American Chemical Society 128 (33): 10808–18. doi:10.1021/ja062082i. PMID 16910676.

- ↑ Brosnan J (1 June 2003). "Interorgan amino acid transport and its regulation". Journal of Nutrition 133 (6 Suppl 1): 2068S–72S. PMID 12771367. http://jn.nutrition.org/cgi/content/full/133/6/2068S.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 69.2 Perrett D, David (2007). "From 'protein' to the beginnings of clinical proteomics". Proteomics — Clinical Applications 1 (8): 720–38. doi:10.1002/prca.200700525.

- ↑ New Oxford Dictionary of English

- ↑ Reynolds JA, Tanford C (2003). Nature's Robots: A History of Proteins (Oxford Paperbacks). Oxford University Press, USA. p. 15. ISBN 0-19-860694-X.

- ↑ Pauling L, Corey RB, Branson HR, L. (1951). "The structure of proteins: two hydrogen-bonded helical configurations of the polypeptide chain" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U.S.A. 37: 235–40. doi:10.1073/pnas.37.5.235. http://www.pnas.org/site/misc/Protein8.pdf.

- ↑ Kauzmann W (1956). "Structural factors in protein denaturation". Journal of Cellular Physiology. Supplement 47 (Suppl 1): 113–31. doi:10.1002/jcp.1030470410. PMID 13332017.

- ↑ Kauzmann W (1959). "Some factors in the interpretation of protein denaturation". Advances in Protein Chemistry 14: 1–63. doi:10.1016/S0065-3233(08)60608-7. PMID 14404936.

- ↑ Kalman SM, Linderstrom-Lang K, Ottesen M, Richards FM (1955). "Degradation of ribonuclease by subtilisin". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 16 (2): 297–99. doi:10.1016/0006-3002(55)90224-9. PMID 14363272.

- ↑ Sanger F (1949). "The terminal peptides of insulin". Biochemical Journal 45 (5): 563–74. PMID 15396627.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1

- ↑ "RCSB Protein Data Bank". http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/home/home.do. Retrieved 2009-04-14.

- ↑ Zhou ZH (2008). "Towards atomic resolution structural determination by single-particle cryo-electron microscopy". Current Opinion in Structural Biology 18 (2): 218–28. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2008.03.004. PMID 18403197. PMC 2714865. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0959-440X(08)00036-5.

- ↑ Keskin O, Tuncbag N, Gursoy A (2008). "Characterization and prediction of protein interfaces to infer protein-protein interaction networks". Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology 9 (2): 67–76. doi:10.2174/138920108783955191. PMID 18393863. http://www.bentham-direct.org/pages/content.php?CPB/2008/00000009/00000002/0003G.SGM. Retrieved 2009-04-14.

References

- Branden C, Tooze J (1999). Introduction to Protein Structure. New York: Garland Pub. ISBN 0-8153-2305-0.

- Murray RF, Harper HW, Granner DK, Mayes PA, Rodwell VW (2006). Harper's Illustrated Biochemistry. New York: Lange Medical Books/McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-146197-3.

- Van Holde KE, Mathews CK (1996). Biochemistry. Menlo Park, Calif: Benjamin/Cummings Pub. Co., Inc. ISBN 0-8053-3931-0.

- Jörg von Hagen, VCH-Wiley 2008 Proteomics Sample Preparation. ISBN 978-3-527-31796-7

External links

- Protein Songs (Stuart Mitchell – DNA Music Project), 'When a "tape" of mRNA passes through the "playing head" of a ribosome, the "notes" produced are amino acids and the pieces of music they make up are proteins.'

Databases and projects

- Comparative Toxicogenomics Database curates protein–chemical interactions, as well as gene/protein–disease relationships and chemical-disease relationships.

- Bioinformatic Harvester A Meta search engine (29 databases) for gene and protein information.

- The Protein Databank (see also PDB Molecule of the Month, presenting short accounts on selected proteins from the PDB)

- Proteopedia – Life in 3D: rotatable, zoomable 3D model with wiki annotations for every known protein molecular structure.

- UniProt the Universal Protein Resource

- The Protein Naming Utility

- Human Protein Atlas

- NCBI Entrez Protein database

- NCBI Protein Structure database

- Human Protein Reference Database

- Human Proteinpedia

- Folding@Home (Stanford University)

Tutorials and educational websites

- "An Introduction to Proteins" from HOPES (Huntington's Disease Outreach Project for Education at Stanford)

- Proteins: Biogenesis to Degradation – The Virtual Library of Biochemistry and Cell Biology

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||