Plutarch

| Plutarch Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus Μέστριος Πλούταρχος |

|

|---|---|

Parallel Lives, Amyot translation, 1565 |

|

| Born | Circa 46 AD Chaeronea, Boeotia |

| Died | Circa 120 AD (aged 74) Delphi, Phocis |

| Occupation | Biographer, essayist, priest, ambassador, magistrate |

| Nationality | Roman (Greek ethnicity) |

| Subjects | Biography, various |

| Literary movement | Middle Platonism, Hellenistic literature |

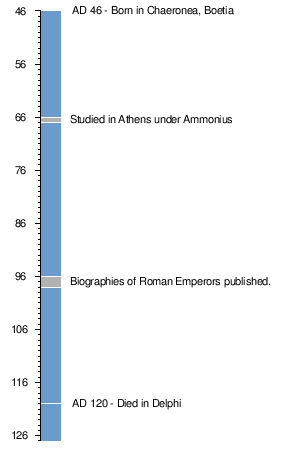

Plutarch, born Plutarchos (Greek: Πλούταρχος) then, on his becoming a Roman citizen, Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus (Μέστριος Πλούταρχος)[1], c. 46 – 120 AD, was a Greek historian, biographer, essayist, and Middle Platonist known primarily for his Parallel Lives and Moralia.[2] He was born to a prominent family in Chaeronea, Boeotia, a town about twenty miles east of Delphi.

Contents |

Early life

Plutarch was born in 46 AD [a] in the small town of Chaeronea, in the Greek region known as Boeotia. His family was wealthy. The name of Plutarch's father has not been preserved, but it was probably Nikarchus, from the common habit of Greek families to repeat a name in alternate generations. The name of Plutarch's grandfather was Lamprias, as he attested in Moralia[3] and in his Life of Antony. His brothers, Timon and Lamprias, are frequently mentioned in his essays and dialogues, where Timon is spoken of in the most affectionate terms. Rualdus, in his 1624 work Life of Plutarchus, recovered the name of Plutarch's wife, Timoxena, from internal evidence afforded by his writings. A letter is still extant, addressed by Plutarch to his wife, bidding her not give way to excessive grief at the death of their two year old daughter, who was named Timoxena after her mother. Interestingly, he hinted at a belief in reincarnation in that letter of consolation.

The exact number of his sons is not certain, although two of them, Autobulus and second Plutarch, are often mentioned. Plutarch's treatise on the Timaeus of Plato is dedicated to them, and the marriage of his son Autobulus is the occasion of one of the dinner-parties recorded in the 'Table Talk.' Another person, Soklarus, is spoken of in terms which seem to imply that he was Plutarch's son, but this is nowhere definitely stated. His treatise on Marriage Questions, addressed to Eurydice and Pollianus, seems to speak of her as having been recently an inmate of his house, but without enabling us to form an opinion whether she was his daughter or not.[4]

Plutarch studied mathematics and philosophy at the Academy of Athens under Ammonius from 66 to 67.[5]. He had a number of influential friends, including Quintus Sosius Senecio and Fundanus, both important senators, to whom some of his later writings were dedicated. Plutarch travelled widely in the Mediterranean world, including central Greece, Sparta, Corinth, Patrae (Patras), Sardes, Alexandria, and two trips to Rome[b].

At some point, Plutarch took up Roman citizenship. As evinced by his new name, Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus, his sponsor for citizenship was Lucius Mestrius Florus, a Roman of consular status whom Plutarch also used as an historial source for his Life of Otho.[6]

| "The soul, being eternal, after death is like a caged bird that has been released. If it has been a long time in the body, and has become tame by many affairs and long habit, the soul will immediately take another body and once again become involved in the troubles of the world. The worst thing about old age is that the soul's memory of the other world grows dim, while at the same time its attachment to things of this world becomes so strong that the soul tends to retain the form that it had in the body. But that soul which remains only a short time within a body, until liberated by the higher powers, quickly recovers its fire and goes on to higher things." |

| Plutarch (The Consolation, Moralia) |

He lived most of his life at Chaeronea, and was initiated into the mysteries of the Greek god Apollo. However, his duties as the senior of the two priests of Apollo at the Oracle of Delphi (where he was responsible for interpreting the auguries of the Pythia) apparently occupied little of his time. He led an active social and civic life while producing an incredible body of writing, much of which is still extant.

For many years Plutarch served as one of the two priests at the temple of Apollo at Delphi (the site of the famous Delphic Oracle) twenty miles from his home. By his writings and lectures Plutarch became a celebrity in the Roman empire, yet he continued to reside where he was born, and actively participated in local affairs, even serving as mayor. At his country estate, guests from all over the empire congregated for serious conversation, presided over by Plutarch in his marble chair. Many of these dialogues were recorded and published, and the 78 essays and other works which have survived are now known collectively as the Moralia.

Work as magistrate and ambassador

In addition to his duties as a priest of the Delphic temple, Plutarch was also a magistrate in Chaeronea and he represented his home on various missions to foreign countries during his early adult years. Plutarch held the office of archon in his native municipality, probably only an annual one which he likely served more than once. He busied himself with all the little matters of the town and undertook the humblest of duties.[7]

The Suda, a medieval Greek encyclopedia, states that emperor Trajan made Plutarch procurator of Illyria. However, most historians consider this unlikely, since Illyria was not a procuratorial province, and Plutarch probably did not speak Illyrian.

According to the 10th century historian George Syncellus, late in Plutarch's life, emperor Hadrian appointed him nominal procurator of Achaea – a position that entitled him to wear the vestments and ornaments of a consul himself.

Plutarch died between the years AD 119 and 127.[c]

Lives of the Roman emperors

The first biographical works to be written by Plutarch were the Lives of the Roman Emperors from Augustus to Vitellius. Of these, only the Lives of Galba and Otho survive. The Lives of Tiberius and Nero are extant only as fragments, provided by Dasmascius (Life of Tiberius, cf. his Life of Isidore)[8] and Plutarch himself (Life of Nero, cf. Galba 2.1), respectively. These early emperors’ biographies were probably published under the Flavian dynasty or during the reign of Nerva (AD 96-98).

There is reason to believe that the two Lives still extant, those of Galba and Otho, “ought to be considered as a single work.” [9] Therefore they do not form a part of the Plutarchian canon of single biographies – as represented by the Life of Aratus of Sicyon and the Life of Artaxerxes (the biographies of Hesiod, Pindar, Crates and Daiphantus were lost). Unlike in these biographies, in Galba-Otho the individual characters of the persons portrayed are not depicted for their own sake but instead serve as an illustration of an abstract principle; namely the adherence or non-adherence to Plutarch’s morally-founded ideal of governing as a Princeps (cf. Galba 1.3; Moralia 328D-E). Arguing from the perspective of Platonian political philosophy (cf. Republic 375E, 410D-E, 411E-412A, 442B-C), in Galba-Otho Plutarch reveals the constitutional principles of the Principate in the time of the civil war after Nero’s death. While morally questioning the behavior of the autocrats, he also gives an impression of their tragic destinies, ruthlessly competing for the throne and finally destroying each other. “The Caesars’ house in Rome, the Palatium, received in a shorter space of time no less than four Emperors,” Plutarch writes, “passing, as it were, across the stage, and one making room for another to enter” (Galba 1).[10]

Galba-Otho was handed down through different channels. It can be found in the appendix to Plutarch’s Parallel Lives as well as in various Moralia manuscripts, most prominently in Maximus Planudes’s edition where Galba and Otho appear as “Opera” XXV and XXVI. Thus it seems reasonable to maintain that Galba-Otho was from early on considered as an illustration of a moral-ethical approach, possibly even by Plutarch himself.[11]

Parallel Lives

Plutarch's best-known work is the Parallel Lives, a series of biographies of famous Greeks and Romans, arranged in pairs to illuminate their common moral virtues and vices. The surviving Lives contain 23 pairs, each with one Greek Life and one Roman Life, as well as four unpaired single Lives.

As is explained in the opening paragraph of his Life of Alexander, Plutarch was not concerned with history so much as the influence of character, good or bad, on the lives and destinies of men. Whereas sometimes he barely touched on epoch-making events, he devoted much space to charming anecdote and incidental triviality, reasoning that this often said far more for his subjects than even their most famous accomplishments. He sought to provide rounded portraits, likening his craft to that of a painter; indeed, he went to tremendous effort (often leading to tenuous comparisons) to draw parallels between physical appearance and moral character. In many ways he must count among the earliest moral philosophers.

Some of the Lives, such as those of Heracles, Philip II of Macedon and Scipio Africanus, no longer exist; many of the remaining Lives are truncated, contain obvious lacunae or have been tampered with by later writers. Extant Lives include those on Solon, Themistocles, Aristides, Pericles, Alcibiades, Nicias, Demosthenes, Pelopidas, Philopoemen, Timoleon, Dion of Syracuse, Alexander the Great, Pyrrhus of Epirus, Romulus, Numa Pompilius, Coriolanus, Aemilius Paullus, Tiberius Gracchus, Gaius Gracchus, Gaius Marius, Sulla, Sertorius, Lucullus, Pompey, Julius Caesar, Cicero, Mark Antony, and Marcus Junius Brutus.

Life of Alexander

Plutarch's Life of Alexander, written as a parallel to that of Julius Caesar, is one of only five extant tertiary sources on the Macedonian conqueror Alexander the Great. It includes anecdotes and descriptions of events that appear in no other source, just as Plutarch's portrait of Numa Pompilius, the putative second king of Rome, holds much that is unique on the early Roman calendar.

Plutarch devotes a great deal of space to Alexander's drive and desire, and strives to determine how much of it was presaged in his youth. He also draws extensively on the work of Lysippus, Alexander's favourite sculptor, to provide what is probably the fullest and most accurate description of the conqueror's physical appearance.

When it comes to his character, however, Plutarch is often rather less accurate, ascribing inordinate amounts of self-control to a man who very often lost it.[12] It is significant, though, that the subject incurs less admiration from his biographer as the narrative progresses and the deeds that it recounts become less savoury.

Much, too, is made of Alexander's scorn for luxury: "He desired not pleasure or wealth, but only excellence and glory." This is most true, for Alexander's tastes grew more extravagant as he grew older only in the last year of his life and only as a means of approaching the image of a ruler his Persian subjects were better accustomed to - thus making it easier for him to succeed in uniting the Greek and Persian worlds together, according to the plan he had announced in his famous Speech given in Opis in 324 BC.

Life of Pyrrhus

Plutarch's Life of Pyrrhus is a key text because it is the main historical account on Roman history for the period from 293 to 264 BC, for which neither Dionysius nor Livy have surviving texts.[13]

Criticism of Parallel Lives

| "It is not histories I am writing, but lives; and in the most glorious deeds there is not always an indication of virtue or vice, indeed a small thing like a phrase or a jest often makes a greater revelation of a character than battles where thousands die." |

| Plutarch (Life of Alexander/Life of Julius Caesar, Parallel Lives, [tr. E.L. Bowie]) |

Plutarch stretches and occasionally fabricates the similarities between famous Greeks and Romans in order to be able to write their biographies as parallel. The lives of Nicias and Crassus, for example, have nothing in common except that both were rich and both suffered great military defeats at the ends of their lives.[14]

In his Life of Pompey, Plutarch praises Pompey's trustworthy character and tactful behaviour in order to conjure a moral judgement that opposes most historical accounts. Plutarch delivers anecdotes with moral points, rather than in-depth comparative analyses of the causes of the fall of the Achaemenid Empire and the Roman Republic,[15] and tends on occasion to fit facts to hypotheses rather than the other, more scholastically acceptable way round.

On the other hand, he generally sets out his moral anecdotes in chronological order (unlike, say, his Roman contemporary Suetonius)[15] and is rarely narrow-minded and unrealistic, almost always prepared to acknowledge the complexity of the human condition where moralising cannot explain it.

Moralia

The remainder of Plutarch's surviving work is collected under the title of the Moralia (loosely translated as Customs and Mores). It is an eclectic collection of seventy-eight essays and transcribed speeches, which includes On Fraternal Affection—a discourse on honour and affection of siblings toward each other, On the Fortune or the Virtue of Alexander the Great—an important adjunct to his Life of the great king, On the Worship of Isis and Osiris (a crucial source of information on Egyptian religious rites)[16], along with more philosophical treatises, such as On the Decline of the Oracles, On the Delays of the Divine Vengeance, On Peace of Mind and lighter fare, such as Odysseus and Gryllus, a humorous dialogue between Homer's Odysseus and one of Circe's enchanted pigs. The Moralia was composed first, while writing the Lives occupied much of the last two decades of Plutarch's own life.

On the Malice of Herodotus

In On the Malice of Herodotus Plutarch criticizes the historian Herodotus for all manners of prejudice and misrepresentation. It has been called the “first instance in literature of the slashing review.” [17] The 19th century English historian George Grote considered this essay a serious attack upon the works of Herodotus, and speaks of the "honourable frankness which Plutarch calls his malignity."[18] Plutarch makes some palpable hits, catching Herodotus out in various errors, but it is also probable that it was merely a rhetorical exercise, in which Plutarch plays devil's advocate to see what could be said against so favourite and well-known a writer.[4] According to Plutarch scholar R. H. Barrow, Herodotus’ real failing in Plutarch’s eyes was to advance any criticism at all of those states that saved Greece from Persia. “Plutarch,” he concluded, “is fanatically biased in favor of the Greek cities; they can do no wrong.”[19]

Questions

Book IV of the Moralia contains the Roman and Greek Questions. The customs of Romans and Greeks are illuminated in little essays that pose questions such as 'Why were patricians not permitted to live on the Capitoline?' (no. 91) and then suggests answers to them, often several mutually exclusive.

Pseudo-Plutarch

Pseudo-Plutarch is the conventional name given to the unknown authors of a number of pseudepigrapha attributed to Plutarch. Some editions of the Moralia include several works now known to be pseudepigrapha: among these are the Lives of the Ten Orators (biographies of the Ten Orators of ancient Athens, based on Caecilius of Calacte), The Doctrines of the Philosophers, and On Music. One "pseudo-Plutarch" is held responsible for all of these works, though their authorship is of course unknown. The thoughts and opinions recorded are not Plutarch's and come from a slightly later era, though they are all classical in origin.

Lost works

The Romans loved the Lives, and enough copies were written out over the centuries so that a copy of most of the lives managed to survive to the present day. Some scholars, however, believe that only a third to one-half of Plutarch’s corpus is extant. The lost works of Plutarch are determined by references in his own texts to them and from other authors' references over time. There are traces of twelve more Lives that are now lost.[20]

Plutarch's general procedure for the Lives was to write the life of a prominent Greek, then cast about for a suitable Roman parallel, and end with a brief comparison of the Greek and Roman lives. Currently, only nineteen of the parallel lives end with a comparison while possibly they all did at one time. Also missing are many of his Lives which appear in a list of his writings, those of Hercules, the first pair of Parallel Lives, Scipio Africanus and Epaminondas, and the companions to the four solo biographies. Even the lives of such important figures as Augustus, Claudius and Nero have not been found and may be lost forever.[17][21]

Philosophy

Plutarch was a Platonist, but was open to the influence of the Peripatetics, and in some details even to Stoicism despite his polemics against their principles.[22] He rejected absolutely only Epicureanism.[22] He attached little importance to theoretical questions and doubted the possibility of ever solving them.[23] He was more interested in moral and religious questions.[23] In opposition to Stoic materialism and Epicurean "atheism" he cherished a pure idea of God that was more in accordance with Plato.[23] He adopted a second principle (Dyad) in order to explain the phenomenal world.[23] This principle he sought, however, not in any indeterminate matter but in the evil world-soul which has from the beginning been bound up with matter, but in the creation was filled with reason and arranged by it.[23] Thus it was transformed into the divine soul of the world, but continued to operate as the source of all evil.[23] He elevated God above the finite world, and thus daemons became for him agents of God's influence on the world. He strongly defends freedom of the will, and the immortality of the soul.[23]

Platonic-Peripatetic ethics were upheld by Plutarch against the opposing theories of the Stoics and Epicureans.[23] The most characteristic feature of Plutarch's ethics is, however, its close connection with religion.[24] However pure Plutarch's idea of God is, and however vivid his description of the vice and corruption which superstition causes, his warm religious feelings and his distrust of human powers of knowledge led him to believe that God comes to our aid by direct revelations, which we perceive the more clearly the more completely that we refrain in "enthusiasm" from all action; this made it possible for him to justify popular belief in divination in the way which had long been usual among the Stoics.[24] His attitude to popular religion was similar. The gods of different peoples are merely different names for one and the same divine Being and the powers that serve it.[24] The myths contain philosophical truths which can be interpreted allegorically.[24] Thus Plutarch sought to combine the philosophical and religious conception of things and to remain as close as possible to tradition.[24]

Influence

Plutarch's writings had an enormous influence on English and French literature. Shakespeare in his plays paraphrased parts of Thomas North's translation of selected Lives, and occasionally quoted from them in verbatim.[25]

Ralph Waldo Emerson and the Transcendentalists were greatly influenced by the Moralia — so much so, in fact, that Emerson called the Lives "a bible for heroes" in his glowing introduction to the five-volume 19th-century edition.[26] He also opined that it was impossible to "read Plutarch without a tingling of the blood; and I accept the saying of the Chinese Mencius: 'A sage is the instructor of a hundred ages. When the manners of Loo are heard of, the stupid become intelligent, and the wavering, determined.'"[27]

Montaigne's own Essays draw extensively on Plutarch's Moralia and are consciously modelled on the Greek's easygoing and discursive inquiries into science, manners, customs and beliefs. Essays contains more than 400 references to Plutarch and his works.[17]

James Boswell quoted Plutarch on writing lives, rather than biographies, in the introduction to his own Life of Samuel Johnson. Other admirers included Ben Jonson, John Dryden, Alexander Hamilton, John Milton, and Francis Bacon, as well as such disparate figures as Cotton Mather and Robert Browning.

Plutarch's influence declined in the 19th and 20th centuries, but it remains embedded in the popular ideas of Greek and Roman history.

Translations of Lives and Moralia

There are translations in Latin, English, French, German, Italian and Polish.

Italian translations

Giuliano Pisani, Moralia I - «La serenità interiore» e altri testi sulla terapia dell'anima, with Greek text, Italian translation, introduction and notes, La Biblioteca dell'Immagine, Pordenone 1989, pp. LIX-508 (De tranquillitate animi; De virtute et vitio; De virtute morali; An virtus doceri possit; Quomodo quis suos in virtute sentiat profectus; Animine an corporis affectiones sint peiores; De vitioso pudore; De cohibenda ira; De garrulitate; De curiositate ; De invidia et odio ; De cupiditate divitiarum)

Giuliano Pisani, Moralia II - L'educazione dei ragazzi, with Greek text, Italian translation, introduction and notes, La Biblioteca dell'Immagine, Pordenone, 1990, pp. XXXVIII-451 (De liberis educandis; Quomodo adolescens poetas audire debeat ; De recta ratione audiendi ; De musica, in collaboration with Leo Citelli)

Giuliano Pisani, Moralia III - Etica e politica, with Greek text, Italian translation, introduction and notes, La Biblioteca dell'Immagine, Pordenone, 1992, pp. XLIII-490 (Praecepta gerendae rei publicae; An seni sit gerenda res publica; De capienda ex inimicis utilitate; De se ipsum citra invidiam laudando; Maxime cum principibus philosopho esse disserendum; Ad principem ineruditum; De unius in republica dominatione, populari statu et paucorum imperio; De exilio)

Giuliano Pisani, Plutarco, Vite di Lisandro e Silla, Fondazione Lorenzo Valla, 1997 (in collaboration with Maria Gabriella Angeli Bertinelli, Mario Manfredini, Luigi Piccirilli).

French translations

Jacques Amyot's translations brought Plutarch's works to Western Europe. He went to Italy and studied the Vatican text of Plutarch, from which he published a French translation of the Lives in 1559 and Moralia in 1572, which were widely read by educated Europe.[28] Amyot's translations had as deep an impression in England as France, because Thomas North later published his English translation of the Lives in 1579 based on Amyot’s French translation instead of the original Greek.

English translations

Plutarch's Lives were translated into English, from Amyot's version, by Sir Thomas North in 1579. The complete Moralia was first translated into English from the original Greek by Philemon Holland in 1603.

In 1683, John Dryden began a life of Plutarch and oversaw a translation of the Lives by several hands and based on the original Greek. This translation has been reworked and revised several times, most recently in the nineteenth century by the English poet and classicist Arthur Hugh Clough which can be found in The Modern Library Random House, Inc. translation.

From 1901–1912, American classicist Bernadotte Perrin produced a new translation of the Lives for the Loeb Classical Library series. The Moralia are also included in the Loeb series, though are translated by various authors.

Latin translations

There are multiple translations of Parallel Lives into Latin, most notably the one titled "Pour le Dauphin" (French for "for the Prince") written by a scribe in the court of Louis XV of France and a 1470 Ulrich Han translation.

German translations

Johann Friedrich Salomon Kaltwasser

Plutarch's Lives and Moralia were translated into German by Johann Friedrich Salomon Kaltwasser:

- Vitae parallelae. Vergleichende Lebensbeschreibungen. 10 Bände. Magdeburg 1799-1806.

- Moralia. Moralische Abhandlungen. 9 Bde. Frankfurt a.M. 1783-1800.

Subsequent German translations

- Biographies

- Konrat Ziegler (Hrsg.): Große Griechen und Römer. 6 Bde. Zürich 1954-1965. (Bibliothek der alten Welt).

- Moralia

- Konrat Ziegler (Hrsg.):Plutarch. Über Gott und Vorsehung, Dämonen und Weissagung, Zürich 1952. (Bibliothek der alten Welt)

- Bruno Snell (Hrsg.):Plutarch. Von der Ruhe des Gemüts - und andere Schriften, Zürich 1948. (Bibliothek der alten Welt)

- Hans-Josef Klauck (Hrsg.): Plutarch. Moralphilosophische Schriften, Stuttgart 1997. (Reclams Universal-Bibliothek)

- Herwig Görgemanns (Hrsg.):Plutarch. Drei Religionsphilosophische Schriften, Düsseldorf 2003. (Tusculum)

See also

- Middle Platonism

Notes

a. ^ Plutarch was probably born during the reign of the Roman Emperor Claudius and between 45 AD and 50 AD. The exact date is debated.[4]

b. ^ Plutarch was once believed to have spent 40 years in Rome, but it is currently thought that he traveled to Rome once or twice for a short period.

c. ^ Plutarch died between the years 119 AD and 127 AD.

Footnotes

- ↑ The name Mestrius or Lucius Mestrius was taken by Plutarch, as was common Roman practice, from his patron for citizenship in the empire; in this case Lucius Mestrius Florus, a Roman consul.

- ↑ "Plutarch". Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy.

- ↑ Symposiacs, Book IX, questions II & III

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Aubrey Stewart, George Long. "Life of Plutarch". Plutarch's Lives, Volume I (of 4). The Gutenberg Project. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/14033/14033.txt. Retrieved 2007-01-03.

- ↑ "Plutarch Bio(46c.-125)". The Online Library of Liberty. http://oll.libertyfund.org/Intros/Plutarch.php. Retrieved 2006-12-06.

- ↑ Plutarch, Otho 14.1

- ↑ Clough, Arthur Hugh. "Introduction". Plutarch's Lives. Liberty Library of Constitutional Classics. http://www.constitution.org/rom/plutarch/intro.htm.

- ↑ Ziegler, Konrad, Plutarchos von Chaironeia (Stuttgart 1964), 258. Citation translated by the author.

- ↑ Cf. among others, Holzbach, M.-C.(2006). Plutarch: Galba-Otho und die Apostelgeschichte : ein Gattungsvergleich. Religion and Biography, 14 (ed.by Detlev Dormeyer et al.). Berlin London: LIT, p.13

- ↑ The citation from Galba was extracted from the Dryden translation as given at the MIT Internet Classics Archive

- ↑ Cf. Holzbach, op.cit.,24

- ↑ The murder of Cleitus the Black, which Alexander instantly and deeply regretted, is commonly cited to this end.

- ↑ Cornell, T.J. (1995). "Introduction". The Beginnings of Rome: Italy and Rome from the Bronze Age to the Punic Wars (c. 1000-264 BC). Routledge. pp. 3.

- ↑ Plutarch (1972). "Translator's Introduction". Fall Of The Roman Republic: Six Lives by Plutarch. translated by Rex Warner. Penguin Books. p. 8.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Plutarch of Chaeronea". Livius.Org. http://www.livius.org/pi-pm/plutarch/plutarch.htm. Retrieved 2006-12-06.

- ↑ Plutarch; translated by Frank Cole Babbitt. "Isis and Osiris". http://altreligion.about.com/library/texts/bl_isisandosiris.htm. Retrieved 2006-12-10.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Kimball, Roger. "Plutarch & the issue of character". The New Criterion Online. http://www.newcriterion.com/archive/19/dec00/plutarch.htm. Retrieved 2006-12-11.

- ↑ Grote, George (2000-10-19) [1830]. A History of Greece: From the Time of Solon to 403 B.C.. Routledge. p. 203.

- ↑ Barrow, R.H. (1979) [1967]. Plutarch and His Times.

- ↑ "Translator's Introduction". The Parallel Lives (Vol. I ed.). Loeb Classical Library Edition. http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Lives/Introduction*.html.

- ↑ McCutchen, Wilmot H.. "Plutarch - His Life and Legacy". http://www.e-classics.com/plutarch.htm. Retrieved 2006-12-10.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Eduard Zeller, Outlines of the History of Greek Philosophy, 13th edition, page 306

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 23.6 23.7 Eduard Zeller, Outlines of the History of Greek Philosophy, 13th edition, page 307

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 Eduard Zeller, Outlines of the History of Greek Philosophy, 13th edition, page 308

- ↑ Honigmann 1959.

- ↑ Emerson, Ralph Waldo. "Introduction". In William W. Goodwin. Plutarch's Morals. London: Sampson, Low. p. xxi.

- ↑ Emerson, Ralph Waldo. "Uses of Great Men". Representative Men.

- ↑ "Amyot, Jacques (1513-1593)". Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition (1910-1911).

References

- Blackburn, Simon (1994). Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Russell, D.A. (2001) [1972]. Plutarch. Duckworth Publishing. ISBN 978-1853996207.

- Duff, Timothy (2002) [1999]. Plutarch's Lives: Exploring Virtue and Vice. UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199252749.

- Hamilton, Edith. The Echo of Greece. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 194. ISBN 0-393-00231-4.

- Holzbach, M.-C. (2006). Plutarch: Galba-Otho und die Apostelgeschichte: ein Gattungsvergleich. Religion and Biography, 14 (ed.by Detlev Dormeyer et al.). Berlin London: LIT. ISBN 382589603X.

- Honigmann, E. A. J. "Shakespeare's Plutarch." Shakespeare Quarterly, 1959: 25-33.

- Wardman, Alan. Plutarch's "Lives". Elek. p. 274. ISBN 0236176226.

External links

Plutarch's works

| Wikisource has original text related to this article:

Plutarch

|

- Works of Plutarch at the University of Adelaide Library.

- Plutarch at LacusCurtius (the Lives, On the Fortune or Virtue of Alexander, On the Fortune of the Romans, Roman Questions, Isis and Osiris, "On the Face in the Moon" and other excerpts of the Moralia)

- Works by Plutarch at Project Gutenberg

- A biography of Plutarch is included in: Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans at Project Gutenberg, 18th century English translation under the editorship of Dryden (further edited by Arthur Hugh Clough).

- De Defectu Oraculorum

- Isis and Osiris

- The Lives, North's translation (PDF format).

- Bioi Paralleloi (Parallel Lives, Βίοι παράλληλοι (Greek))

Secondary material

- Plutarch entry by George Karamanolis in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Plutarch of Chaeronea by Jona Lendering at Livius.Org

- The International Plutarch Society

- When the gods ceased to speak Lecture about Plutarch's De Defectu Oraculorum, held at the New Testament Society of South Africa in Stellenbosch.

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||