Plasmodium

| Plasmodium | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Chromalveolata |

| Superphylum: | Alveolata |

| Phylum: | Apicomplexa |

| Class: | Aconoidasida |

| Order: | Haemosporida |

| Family: | Plasmodiidae |

| Genus: | Plasmodium |

| Species | |

|

Plasmodium accipiteris |

|

Plasmodium is a genus of parasitic protists. Infection by these organisms is known as malaria. The genus Plasmodium was created in 1885 by Marchiafava and Celli. Currently over 200 species of this genus are recognized and new species continue to be described.[1] [2]

Of the over 200 known species of Plasmodium, at least 11 species infect humans. Other species infect animals, including monkeys, rodents, birds, and reptiles. The parasite always has two hosts in its life cycle: a mosquito vector and a vertebrate host.

History

The organism itself was first seen by Laveran on November 6, 1880 at a military hospital in Constantine, Algeria, when he discovered a microgametocyte exflagellating. In 1885, similar organisms were discovered within the blood of birds in Russia. There was brief speculation that birds might be involved in the transmission of malaria; in 1894 Patrick Manson proposed the existence of an exoerythrocytic stage in the life cycle: this was later confirmed by Short, Garnham, Covell and Shute (in 1948) who found Plasmodium vivax in the human liver.

Life cycle

All the Plasmodium species causing malaria in humans are transmitted by mosquito species of the genus Anopheles. Species of the mosquito genera Aedes, Culex, Culiseta, Mansonia and Theobaldia can also transmit malaria but not to humans.

Both sexes of mosquitos live on nectar. Because nectar's protein content alone is insufficient for oogenesis (egg production) one or more blood meals is needed by the female. Only female mosquitoes bite.

The life cycle of Plasmodium is complex. Sporozoites from the saliva of a biting female mosquito are transmitted to either the blood or the lymphatic system of the recipient.[3] It has been known for time that the parasites block the salivary ducts of the mosquito and as a consequence the insect normally requires multiple attempts to obtain blood. The reason for this has not been clear. It is now known that the multiple attempts by the mosquito may contribute to immunological tolerance of the parasite.[4]

The sporozoites then migrate to the liver and invade hepatocytes. The parasite matures in the hepatocyte to a schizont containing many merozoites in it. In some Plasmodium species, such as Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium ovale, the parasite in the hepatocyte may not achieve maturation to a schizont immediately but remain as a latent or dormant form and called a hypnozoite. Although Plasmodium falciparum is not considered to have a hypnozoite form.[5] this may not be entirely correct (vide infra).

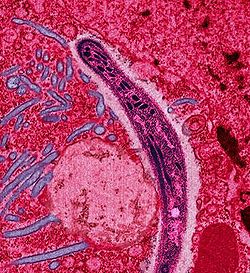

The development from the hepatic stages to the erythrocytic stages has, until very recently, been obscure. In 2006 it was shown that the parasite buds off the hepatocytes in merosomes containing hundreds or thousands of merozoites.[6] These merosomes lodge in the pulmonary capillaries and slowly disintegrate there over 48–72 hours releasing merozoites. [7] Erythrocyte invasion is enhanced when blood flow is slow and the cells are tightly packed: both of these conditions are found in the alveolar capillaries.

Within the erythrocytes the merozoite grow first to a ring-shaped form and then to a larger trophozoite form. In the schizont stage, the parasite divides several times to produce new merozoites, which leave the red blood cells and travel within the bloodstream to invade new red blood cells. The parasite feeds by ingesting haemoglobin and other materials from red blood cells and serum. The feeding process damages the erythrocytes. Details of this process have not been studied in species other than Plasmodium falciparum so generalizations may be premature at this time.

Invasion of erythrocyte precursors has only recently been studied.[8] The earliest stage susceptible to infection were the orthoblasts - the stage immediately preceding the reticulocyte stage which in turn is the immediate precursor to the mature erythrocyte.

At the molecular level a set of enzymes known as plasmepsins which are aspartic acid proteases are used to degrade hemoglobin. The parasite digests 70-80% of the erythrocyte's haemoglobin[9] The reason proposed for this apparently excessive digestion of haemoglobin is the colloid-osmotic hypothesis[10] which suggests that the digestion of haemoglobin increases the osmotic pressure within the infected erythrocyte leading to its premature rupture and subsequent death of the parasite. To avoid this fate much of the haemoglobin is digested and exported from the erythrocyte. This hypothesis has been experimentally confirmed.[11]

Most merozoites continue this replicative cycle but some merozoites differentiate into male or female sexual forms (gametocytes) (also in the blood), which are taken up by the female mosquito.

In the mosquito's midgut, the gametocytes develop into gametes and fertilize each other, forming motile zygotes called ookinetes. The ookinetes penetrate and escape the midgut, then embed themselves onto the exterior of the gut membrane. Here they divide many times to produce large numbers of tiny elongated sporozoites. These sporozoites migrate to the salivary glands of the mosquito where they are injected into the blood and subcutaneous tissue of the next host the mosquito bites. The majority appear to be injected into the subcutaneous tissue from which they migrate into the capillaries. A proportion are ingested by macrophages and still others are taken up by the lymphatic system where they are presumably destroyed. The sporozoites which successfully enter the blood stream move to the liver where they begin the cycle again.

Reactivation of the hypnozoites has been reported for up to 30 years after the initial infection in humans. The factors precipating this reactivation are not known. In the species Plasmodium malariae, Plasmodium ovale[12] and Plasmodium vivax[13] hypnozoites have been shown to occur. It is not yet known if hypnozoite reactivaction occurs with any of the remaining species that infect humans but this is presumed to be the case.

The pattern of alternation of sexual and asexual reproduction which may seem confusing at first is a very common pattern in parasitic species. The evolutionary advantages of this type of life cycle were recognised by Gregor Mendel.

Under favourable conditions asexual reproduction is superior to sexual as the parent is well adapted to its environment and its descendents share these genes. Transferring to a new host or in times of stress, sexual reproduction is generally superior as this produces a shuffling of genes which on average at a population level will produce individuals better adapted to the new environment.

Possible dormancy of Plasmodium falciparum malaria

A report of P. falciparum malaria in a patient with sickle cell anemia four years after exposure to the parasite has been published.[14] A second report that P. falciparum malaria had become symptomatic eight years after leaving an endemic area has also been published.[15]

A third case of an apparent recurrence nine years after leaving an endemic area of P. falciparum malaria has now been reported .[16] A fourth case of recurrence in a patient with lung cancer has been reported.[17] Two cases in pregnant women both from Africa but who had not lived there for over a year have been reported.[18]

It seems that at least occasionally P. falciparum has a dormant stage. If this is in fact the case, eradication or control of this organism may be more difficult than previously believed.

Quiescent forms

Developmental arrest was induced by in vitro culture of P. falciparum in the presence of sub lethal concentrations of artemisinin.[19] The drug induces a subpopulation of ring stages into developmental arrest. At the molecular level this is associated with overexpression of heat shock and erythrocyte binding surface proteins with the reduced expression of a cell-cycle regulator and a DNA biosynthesis protein.

Potentially dormant forms of Plasmodium

A small number of potentially dormant forms of Plasmodium parasites both in vitro and in vivo have been observed.

The schizont stage-infected erythrocyte in an experimental culture of P. falciparum, F32 was suppressed to a low level with the use of atovaquone.[20] The parasites resumed growth several days after the drug was removed from the culture.

More than a hundred late-stage trophozoites or early schizont infected erythrocytes of P. falciparum in a case of placental malaria of a Tanzanian woman were found to form a nidus in an intervillous space of placenta.[21] While such a concentration of parasites in placental malaria is rare, placental malaria cannot give rise to persistent infection as pregnancy in humans normally lasts only 9 months.

Macrophages containing merozoites dispersed in their cytoplasm, called 'merophores', were observed in P. vinckei petteri - an organism that causes murine malaria.[22] Similar merophores were found in the polymorph leukocytes and macrophages of other murine malaria parasite, P. yoelii nigeriensis[23] and P. chabaudi chabaudi. All these species unlike P. falciparum are known to produce hyponozoites that may cause a relapse. The finding of Landau et al.[22] on the presence of malaria parasites inside lymphatics suggest a mechanism for the recrudescence and chronicity of malaria infection.[24]

Evolution

As of 2007, DNA sequences are available from less than sixty species of Plasmodium and most of these are from species infecting either rodent or primate hosts. The evolutionary outline given here should be regarded as speculative, and subject to revision as more data becomes available.

The Apicomplexa (the phylum to which Plasmodium belongs) are thought to have originated within the Dinoflagellates — a large group of photosynthetic protists. It is thought that the ancestors of the Apicomplexa were originally prey organisms that evolved the ability to invade the intestinal cells and subsequently lost their photosynthetic ability. Many of the species within the Apicomplexia still possess plastids (the organelle in which photosynthesis occurs in photosynthetic eukaryotes), and some that lack plastids nonetheless have evidence of plastid genes within their genomes. In the majority of such species, the plastids are not capable of photosynthesis. Their function is not known, but there is suggestive evidence that they may be involved in reproduction.

Some extant dinoflagellates, however, can invade the bodies of jellyfish and continue to photosynthesize, which is possible because jellyfish bodies are almost transparent. In host organisms with opaque bodies, such an ability would most likely rapidly be lost. The 2008 description of a photosynthetic protist related to the Apicomplexia with a functional plastid supports this hypothesis.[25]

Current (2007) theory suggests that the genera Plasmodium, Hepatocystis and Haemoproteus evolved from one or more Leukocytozoon species. Parasites of the genus Leukocytozoan infect white blood cells (leukocytes) and liver and spleen cells, and are transmitted by 'black flies' (Simulium species) — a large genus of flies related to the mosquitoes.

It is thought that Leukocytozoon evolved from a parasite that spread by the orofaecal route and which infected the intestinal wall. At some point this parasite evolved the ability to infect the liver. This pattern is seen in the genus Cryptosporidium, to which Plasmodium is distantly related. At some later point this ancestor developed the ability to infect blood cells and to survive and infect mosquitoes. Once vector transmission was firmly established, the previous orofecal route of transmission was lost.

Molecular evidence suggests that a reptile - specifically a squamate - was the first vertebrate host of Plasmodium. Birds were the second vertebrate hosts with mammals being the most recent group of vertebrates infected.[26].

Leukocytes, hepatocytes and most spleen cells actively phagocytose particulate matter, which makes the parasite's entry into the cell easier. The mechanism of entry of Plasmodium species into erythrocytes is still very unclear, as it takes place in less than 30 seconds. It is not yet known if this mechanism evolved before mosquitoes became the main vectors for transmission of Plasmodium.

The genus Plasmodium evolved (presumably from its Leukocytozoon ancestor) about 130 million years ago, a period that is coincidental with the rapid spread of the angiosperms (flowering plants). This expansion in the angiosperms is thought to be due to at least one genomic duplication event. It seems probable that the increase in the number of flowers led to an increase in the number of mosquitoes and their contact with vertebrates.

Mosquitoes evolved in what is now South America about 230 million years ago. There are over 3500 species recognized, but to date their evolution has not been well worked out, so a number of gaps in our knowledge of the evolution of Plasmodium remain. There is evidence of a recent expansion of Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles arabiensis populations in the late Pleistocene in Nigeria.[27]

The reason why a relatively limited number of mosquitoes should be such successful vectors of multiple diseases is not yet known. It has been shown that, among the most common disease-spreading mosquitoes, the symbiont bacterium Wolbachia are not normally present.[28] It has been shown that infection with Wolbachia can reduce the ability of some viruses and Plasmodium to infect the mosquito, and that this effect is Wolbachia-strain specific.

Biology

All Plasmodium species examined to date have 14 chromosomes, with one mitochondrion and one plastid genome. The chromosomes which have been sequenced vary in length from 500 kilobases to 3.5 megabases. It is presumed that this is the pattern throughout the genus. The typical chromosome number of Leukocytozoon has not yet been established.

The genome of four Plasmodium species have been sequenced. These species are Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium knowlesi, Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium yoelli. All these species have 14 chromosomes and genomes of about 25 megabases, results consistent with earlier estimates.

The biology of these organisms is more fully described on the Plasmodium falciparum biology page.

Taxonomy

Plasmodium belongs to the family Plasmodiidae (Levine, 1988), order Haemosporidia and phylum Apicomplexa. There are currently 450 recognised species in this order. Many species of this order are undergoing reexamination of their taxonomy with DNA analysis. It seems likely that many of these species will be re-assigned after these studies have been completed.[29][30] For this reason the entire order is outlined here.

Order Haemosporida

- Genus Bioccala

Family Haemoproteidae

- Genus Haemoproteus

- Subgenus Parahaemoproteus

- Subgenus Haemoproteus

Family Garniidae

- Genus Fallisia

- Subgenus Plasmodioides

Family Leucocytozoidae

- Genus Leukocytozoon

- Subgenus Leucocytozoon

- Subgenus Akiba

Family Plasmodiidae

- Genus Billbraya

- Genus Dionisia

- Genus Hepatocystis

- Genus Mesnilium

- Genus Nycteria

- Genus Plasmodium

- Subgenus Asiamoeba

- Subgenus Bennettinia

- Subgenus Carinamoeba

- Subgenus Fallisia

- Subgenus Garnia

- Subgenus Giovannolaia

- Subgenus Haemamoeba

- Subgenus Huffia

- Subgenus Lacertaemoba

- Subgenus Laverania

- Subgenus Novyella

- Subgenus Ophidiella

- Subgenus Plasmodium

- Subgenus Paraplasmodium

- Subgenus Sauramoeba

- Subgenus Vinckeia

- Genus Polychromophilus

- Genus Rayella

- Genus Saurocytozoon

Diagnostic characteristics of the genus Plasmodium

- Merogony occurs both in erythrocytes and other tissues

- Merozoites, schizonts or gametocytes can be seen within erythrocytes and may displace the host nucleus

- Merozoites have a “signet-ring” appearance due to a large vacuole that forces the parasite’s nucleus to one pole

- Schizonts are round to oval inclusions that contain the deeply staining merozoites

- Forms gamonts in erythrocytes

- Gametocytes are 'halter-shaped' similar to Haemoproteus but the pigment granules are more confined

- Hemozoin is present (except in the subgenus Garnia)

- Vectors are either mosquitos or sandflies

- Vertebrate hosts include mammals, birds and reptiles

Phylogenetic trees

The relationship between a number of these species can be seen on the Tree of Life website. Perhaps the most useful inferences that can be drawn from this phylogenetic tree are:

- P. falciparum and P. reichenowi (subgenus Laverania) branched off early in the evolution of this genus

- The genus Hepatocystis is nested within (paraphytic with) the genus Plasmodium

- The primate (subgenus Plasmodium) and rodent species (subgenus Vinckeia) form distinct groups

- The rodent and primate groups are relatively closely related

- The lizard and bird species are intermingled

- Although Plasmodium elongatum (subgenus Haemamoeba) and Plasmodium elongatum (subgenus Huffia) appear be related here there are so few bird species (three) included, this tree may not accurately reflect their real relationship.

- While no snake parasites have been included these are likely to group with the lizard-bird division

While this tree contains a considerable number of species, DNA sequences from many species in this genus have not been included - probably because they are not available yet. Because of this problem, this tree and any conclusions that can be drawn from it should be regarded as provisional.

Three additional trees are available from the American Museum of Natural History.

These trees agree with the Tree of Life. Because of their greater number of species in these trees, some additional inferences can be made:

- The genus Hepatocystis appears to lie within the primate-rodent clade

- The genus Haemoproteus appears lie within the bird-lizard clade

- The trees are consistent with the proposed origin of Plasmodium from Leukocytozoon

It is also known that the species infecting humans do not form a single clade.[31] In contrast, the species infecting Old World monkeys seem to form a clade. Plasmodium vivax may have originated in Asia and the related species Plasmodium simium appears to be derived through a transfer from the human P. vivax to New World monkey species in South America. This occurred during an indepth study of Howler Monkeys near São Paulo, Brasil.[32]

Another tree concetrating on the species infecting the primates is available here: PLOS site

This tree shows that the 'African' (P. malaria and P. ovale) and 'Asian' (P.cynomogli, P. gonderi, P. semiovale and P. simium) species tend to cluster together into separate clades. P. vivax clusters with the 'Asian' species. The rodent species (P. bergei, P. chabaudi and P. yoelli) form a separate clade. As usual P. falciparum does not cluster with any other species. The bird species (P. juxtanucleare, P. gallinaceum and P. relictum) form a clade that is related to the included Leukocytozoan and Haemoproteus species.

A second tree can be found on the PLoS website: PLOS site This tree concentrates largely on the species infecting primates.

The three bird species included in this tree (P. gallinacium, P. juxtanucleare and P. relictum) form a clade.

Four species (P. billbrayi, P. billcollinsi, P. falciparum and P. reichenowi) form a clade within the subgenus Lavernia. This subgenus is more closely related to the other primate species than to the bird species or the include Leuocytozoan species. Both P. billbrayi and P. billcollinsi infect both the chimpanzee subspecies included in this study (Pan troglodytes troglodytes and Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii). P. falciparum infects the bonbo (Pan paniscus) and P. reichenowi infects only one subspecies (Pan troglodytes troglodytes).

The eleven 'Asian' species included here form a clade with P. simium and P. vivax being clearly closely related as are P. knowseli and P. coatneyi; similarly P. brazillium and P. malariae are related. P. hylobati and P. inui are closely related. P. fragile and P. gonderi appear to be more closely related to P. vivax than to P. malariae.

P. ovale is more closely related to P. malariae than to P. vivax.

Within the 'Asian' clade are three unnamed potential species. One infects each of the two chimpanzee subspecies included in the study (Pan troglodytes troglodytes and Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii). These appear to be related to the P. vivax/P. simium clade.

Two unnamed potential species infect the bonbo (Pan paniscus) and these are related to the P. malariae/P. brazillium clade.

Notes

An analysis of ten 'Asian' species (P. coatneyi, P. cynomolgi, P. fieldi, P. fragile, P. gonderi, P. hylobati, P. inui, P. knowlesi, P. simiovale and P. vivax) suggests that P. coatneyi and P. knowlesi are closely related and that P. fragile is the species most closely related to these two.[33] P. vivax and P. cynomolgi appear to be related.

Unlike other eukaryotes studied to date Plasmodium species have two or three distinct SSU rRNA (18S rRNA) molecules encoded within the genome.[34] These have been divided into types A, S and O. Type A is expressed in the asexual stages; type S in the sexual and type O only in the oocyte. Type O is only known to occur in Plasmodium vivax at present. The reason for this gene duplication is not known but presumably reflects an adaption to the different environments the parasite lives within.

The Asian simian Plasmodium species - Plasmodium coatneyi, Plasmodium cynomolgi, Plasmodium fragile, Plasmodium inui, Plasmodium fieldi, Plasmodium hylobati and Plasmodium simiovale - have a single single S-type-like gene and several A-type-like genes. It seems likely that these species form a clade within the subgenus Plasmodium.

Analysis of the merozoite surface protein in ten species of the Asian clade suggest that this group diversified between 3 and 6.3 million years ago - a period that coincided with the radiation of the macques within South East Asia.[35] The inferred branching order differs from that found from the analysis of other genes suggesting that this phylogenetic tree may be difficult to resolve. Positive selection on this gene was also found.

P. vivax appears to have evolved between 45,000 and 82,000 years ago from a species that infects south east Asian macques.[36] This is consistent with the other evidence of a south eastern origin of this species.

It has been reported that the C terminal domain of the RNA polymerase 2 in the primate infecting species (other than P. falciparum and probably P. reichenowei) appears to be unusual[37] suggesting that the classification of species into the subgenus Plasmodium may have an evolutionary and biological basis.

A report of a new species that clusters with P. falciparum and P. reichenowi in chimpanzees has been published, although to date the species has been identified only from the sequence of its mitochondrion.[38] Further work will be needed to describe this new species, however, it appears to have diverged from the P. falciparum- P. reichenowi clade about 21 million years ago. A second report has confirmed the existence of this species in chimpanzees.[39] This report has also shown that P. falciparum is not a uniquely human parasite as had been previously believed. A third report of P. falciparum has been published. [40] This study investigated two mitochondrial genes (cytB and cox1), one plastid gene (tufA), and one nuclear gene (ldh) in 12 chimpanzees and two gorillas from Cameroon and one lemur from Madagascar. Plasmodium falciparum was found in one gorilla and two chimpanzee samples. Two chimpanzee samples tested positive for Plasmodium ovale and one for Plasmodium malariae. Additionally one chimpanzee sample showed the presence of P. reichenowi and another P. gaboni. A new species - Plasmodium malagasi - was provisionally identified in the lemur. This species seems likely to belong to the Vinckeia subgenus but further work is required.

It has been shown that P. falciparum forms a clade with the species P reichenowi.[41] This clade may have originated between 3 million and 10000 years ago. It is proposed that the origin of P. falciparum may have occurred when its precursors developed the ability to bind to sialic acid Neu5Ac possibly via erythrocyte binding protein 175. Humans lost the ability to make the sialic acid Neu5Gc from its precursor Neu5Ac several million years ago and this may have protected them against infection with P. reichenowi.

The dates of the evolution of the species within the subgenus Laverania have been estimated as follows:[42]

Laverania: 12.0 million years ago (Mya) (95% estimated range: 6.0 - 19.0 Mya)

P. falciparum in humans: 0.2 Mya (range: 0.078 - 0.33 Mya)

P. falciparum in Pan paniscus: 0.77 Mya (range: 0.43 - 1.6 Mya)

P. falciparum in humans and Pan paniscus: 0.85 Mya (0.46 - 1.3 Mya)

P. reichenowi - P. falciparum in Pan paniscus: 2.2 Mya (range: 1.0 - 3.1 Mya)

P. reichenowi - 1.8 Mya (range: 0.6 - 3.2 Mya)

P. billbrayi - 1.1 Mya (range: 0.52 - 1.7 Mya)

P. billcollinsi - 0.97 Mya (range: 0.38 - 1.7 Mya)

A recently (2009) described species (Plasmodium hydrochaeri) that infects capybaras (Hydrochaeris hydrochaeris) may complicate the phylogentics of this genus.[43] This species appears to be most similar to Plasmodium mexicanum a lizard parasite. Further work in this area seems indicated.

Subgenera: discussion

The full taxonomic name of a species includes the subgenus but this is often omitted. The full name indicates some features of the morphology and type of host species. Sixteen subgenera are currently recognised.

The avian species were discovered soon after the description of P. falciparum and a variety of generic names were created. These were subsequently placed into the genus Plasmodium although some workers continued to use the genera Laverinia and Proteosoma for P. falciparum and the avian species respectively. The 5th and 6th Congresses of Malaria held at Istanbul (1953) and Lisbon (1958) recommended the creation and use of subgenera in this genus. Laverinia was applied to the species infecting humans and Haemamoeba to those infecting lizards and birds. This proposal was not universally acepted. Bray in 1955 proposed a definition for the subgenus Plasmodium and a second for the subgenus Laverinia in 1958. Garnham described a third subgenus - Vinckeia - in 1964.

Mammalian species

Two species in the subgenus Laverania are currently recognised: P. falciparum and P. reichenowi. Three additional species - Plasmodium billbrayi, Plasmodium billcollinsi and Plasmodium gaboni - may also exist (based on molecular data) but a full description of these species have not yet been published.[42][44] The presence of elongated gametocytes in several of the avian subgenera and in Laverania in addition to a number of clinical features suggested that these might be closely related. This is no longer thought to be the case.

The type species is Plasmodium falciparum.

Species infecting monkeys and apes (the higher primates) other than those in the subgenus Laverania are placed in the subgenus Plasmodium. The position of the recently described Plasmodium GorA and Plasmodium GorB has not yet been settled.[39] The distinction between P. falciparum and P. reichenowi and the other species infecting higher primates was based on the morphological findings but have since been confirmed by DNA analysis.

The type species is Plasmodium malariae.

Parasites infecting other mammals including lower primates (lemurs and others) are classified in the subgenus Vinckeia. Vinckeia while previously considered to be something of a taxonomic 'rag bag' has been recently shown - perhaps rather surprisingly - to form a coherent grouping.

The type species is Plasmodium bubalis.

Birds

The remaining groupings are based on the morphology of the parasites. Revisions to this system are likely to occur in the future as more species are subject to analysis of their DNA.

The four subgenera Giovannolaia, Haemamoeba, Huffia and Novyella were created by Corradetti et al. for the known avian malarial species.[45] A fifth—Bennettinia—was created in 1997 by Valkiunas.[46] The relationships between the subgenera are the matter of current investigation. Martinsen et al. 's recent (2006) paper outlines what is currently (2007) known.[47] The subgenera Haemamoeba, Huffia, and Bennettinia appear to be monphylitic. Novyella appears to be well defined with occasional exceptions. The subgenus Giovannolaia needs revision.[48]

P. juxtanucleare is currently (2007) the only known member of the subgenus Bennettinia.

Nyssorhynchus is an extinct subgenus of Plasmodium. It has one known member - Plasmodium dominicum

Reptiles

Unlike the mammalian and bird malarias those species (more than 90 currently known) that infect reptiles have been more difficult to classify.

In 1966 Garnham classified those with large schizonts as Sauramoeba, those with small schizonts as Carinamoeba and the single then known species infecting snakes (Plasmodium wenyoni) as Ophidiella.[49] He was aware of the arbitrariness of this system and that it might not prove to be biologically valid. Telford in 1988 used this scheme as the basis for the currently accepted (2007) system.[50]

These species have since been divided in to 8 genera - Asiamoeba, Carinamoeba, Fallisia, Garnia, Lacertamoeba, Ophidiella, Paraplasmodium and Sauramoeba. Three of these genera (Asiamoeba, Lacertamoeba and Paraplasmodium) were created by Telford in 1988. Another species (Billbraya australis) described in 1990 by Paperna and Landau and is the only known species in this genus. This species may turn out to be another subgenus of lizard infecting Plasmodium.

Classification criteria for subgenera

Bird species

There are ~40 recognised bird species. Although over 50 species have been described, several have been rejected as being invalid.

With the exception of P. elongatum the exoerythrocytic stages occur in the endothelial cells and those of the macrophage-lymphoid system. The exoerythrocytic stages of P. elongatum parasitise the blood forming cells.

The various subgenera are first distinguished on the basis of the morphology of the mature gametocytes. Those of subgenus Haemamoeba are round or oval while those of the subgenera Giovannolaia, Huffia and Novyella are elongated. These latter genera are distinguished on the basis of the size of the schizonts: Giovannolaia and Huffia have large schizonts while those of Novyella are small.

Species in the subgenus Bennettinia have the following characteristics:

The type species is Plasmodium juxtanucleare.

Species in the subgenus Giovannolaia have the following characteristics:

- Schizonts contain plentiful cytoplasm, are larger than the host cell nucleus and frequently displace it. They are found only in mature erythrocytes.

- Gametocytes are elongated.

- Exoerythrocytic schizogony occurs in the mononuclear phagocyte system.

The type species is Plasmodium circumflexum.

Species in the subgenus Haemamoeba have the following characteristics:

- Mature schizonts are larger than the host cell nucleus and commonly displace it.

- Gametocytes are large, round, oval or irregular in shape and are substantially larger than the host nucleus.

The type species is Plasmodium relictum.

Species in the subgenus Huffia have the following characteristics:

- Mature schizonts, while varying in shape and size, contain plentiful cytoplasm and are commonly found in immature erthryocytes.

- Gametocytes are elongated.

The type species is Plasmodium elongatum.

Species in the subgenus Novyella have the following characteristics:

- Mature schizonts are either smaller than or only slightly larger than the host nucleus. They contain scanty cytoplasm.

- Gametocytes are elongated. Sexual stages in this subgenus resemble those of Haemoproteus.

- Exoerythrocytic schizogony occurs in the mononuclear phagocyte system

The type species is Plasmodium vaughani.

Reptile species

All species in these subgenera infect lizards.

Species in the subgenus Asiamoeba have the following characteristics:

Species in the subgenus Carinamoeba have the following characteristics:

- Schizonts normally give rise to less than 8 merozoites

- Schizonts are normally smaller than the host nucleus

The type species is Plasmodium minasense.

Species in the subgenus Fallisia have the following characteristics:

- Non-pigmented asexual and gametocyte forms are found in leukocytes and thrombocytes

Species in the subgenus Garnia have the following characteristics:

- Pigment is absent

Species in the subgenus Lacertaemoba have the following characteristics:

Species in the subgenus Paraplasmodium have the following characteristics:

Species in the subgenus Sauramoeba have the following characteristics:

- Schizonts normally give rise to more than 8 merozoites

- Schizonts are normally larger than the host nucleus

- Non-pigmented gametocytes are typically the only forms found

- Pigmented forms may be found in the leukocytes occasionally

The type species is Plasmodium agamae.

All species in Ophidiella infect snakes

The type species is Plasmodium weyoni.

Notes

- The erythrocytes of both reptiles and birds retain their nucleus, unlike those of mammals. The reason for the loss of the nucleus in mammalian erythocytes remains unknown.

Species listed by subgenera

Plasmodium (Asiamoeba) clelandi

Plasmodium (Asiamoeba) draconis

Plasmodium (Asiamoeba) lionatum

Plasmodium (Asiamoeba) saurocordatum

Plasmodium (Asiamoeba) vastator

Plasmodium (Bennettinia) juxtanucleare

Plasmodium (Carinamoeba) basilisci

Plasmodium (Carinamoeba) clelandi

Plasmodium (Carinamoeba) lygosomae

Plasmodium (Carinamoeba) mabuiae

Plasmodium (Carinamoeba) minasense

Plasmodium (Carinamoeba) rhadinurum

Plasmodium (Carinamoeba) volans

Plasmodium (Fallisia) siamense

Plasmodium (Giovannolaia) anasum

Plasmodium (Giovannolaia) circumflexum

Plasmodium (Giovannolaia) dissanaikei

Plasmodium (Giovannolaia) durae

Plasmodium (Giovannolaia) fallax

Plasmodium (Giovannolaia) formosanum

Plasmodium (Giovannolaia) gabaldoni

Plasmodium (Giovannolaia) garnhami

Plasmodium (Giovannolaia) gundersi

Plasmodium (Giovannolaia) hegneri

Plasmodium (Giovannolaia) lophurae

Plasmodium (Giovannolaia) pedioecetii

Plasmodium (Giovannolaia) pinnotti

Plasmodium (Giovannolaia) polare

Plasmodium (Haemamoeba) cathemerium

Plasmodium (Haemamoeba) coggeshalli

Plasmodium (Haemamoeba) coturnixi

Plasmodium (Haemamoeba) elongatum

Plasmodium (Haemamoeba) gallinaceum

Plasmodium (Haemamoeba) giovannolai

Plasmodium (Haemamoeba) lutzi

Plasmodium (Haemamoeba) matutinum

Plasmodium (Haemamoeba) paddae

Plasmodium (Haemamoeba) parvulum

Plasmodium (Haemamoeba) relictum

Plasmodium (Haemamoeba) tejera

Plasmodium (Huffia) elongatum

Plasmodium (Huffia) hermani

Plasmodium (Lacertaemoba) floridense

Plasmodium (Lacertaemoba) tropiduri

Plasmodium (Laverania) billbrayi

Plasmodium (Laverania) billcollinsi

Plasmodium (Laverania) falciparum

Plasmodium (Laverania) gaboni

Plasmodium (Laverania) reichenowi

Plasmodium (Ophidiella) pessoai

Plasmodium (Ophidiella) tomodoni

Plasmodium (Ophidiella) wenyoni

Plasmodium (Novyella) ashfordi

Plasmodium (Novyella) bertii

Plasmodium (Novyella) bambusicolai

Plasmodium (Novyella) columbae

Plasmodium (Novyella) corradettii

Plasmodium (Novyella) dissanaikei

Plasmodium (Novyella) globularis

Plasmodium (Novyella) hexamerium

Plasmodium (Novyella) jiangi

Plasmodium (Novyella) kempi

Plasmodium (Novyella) lucens

Plasmodium (Novyella) megaglobularis

Plasmodium (Novyella) multivacuolaris

Plasmodium (Novyella) nucleophilum

Plasmodium (Novyella) papernai

Plasmodium (Novyella) parahexamerium

Plasmodium (Novyella) paranucleophilum

Plasmodium (Novyella) rouxi

Plasmodium (Novyella) vaughani

Plasmodium (Nyssorhynchus) dominicum

Plasmodium (Paraplasmodium) chiricahuae

Plasmodium (Paraplasmodium) mexicanum

Plasmodium (Paraplasmodium) pifanoi

Plasmodium (Plasmodium) bouillize

Plasmodium (Plasmodium) brasilianum

Plasmodium (Plasmodium) cercopitheci

Plasmodium (Plasmodium) coatneyi

Plasmodium (Plasmodium) cynomolgi

Plasmodium (Plasmodium) eylesi

Plasmodium (Plasmodium) fieldi

Plasmodium (Plasmodium) fragile

Plasmodium (Plasmodium) georgesi

Plasmodium (Plasmodium) girardi

Plasmodium (Plasmodium) gonderi

Plasmodium (Plasmodium) gora

Plasmodium (Plasmodium) gorb

Plasmodium (Plasmodium) inui

Plasmodium (Plasmodium) jefferyi

Plasmodium (Plasmodium) joyeuxi

Plasmodium (Plasmodium) knowlei

Plasmodium (Plasmodium) hyobati

Plasmodium (Plasmodium) malariae

Plasmodium (Plasmodium) ovale

Plasmodium (Plasmodium) petersi

Plasmodium (Plasmodium) pitheci

Plasmodium (Plasmodium) rhodiani

Plasmodium (Plasmodium) schweitzi

Plasmodium (Plasmodium) semiovale

Plasmodium (Plasmodium) semnopitheci

Plasmodium (Plasmodium) silvaticum

Plasmodium (Plasmodium) simium

Plasmodium (Plasmodium) vivax

Plasmodium (Plasmodium) youngi

Plasmodium (Sauramoeba) achiotense

Plasmodium (Sauramoeba) adunyinkai

Plasmodium (Sauramoeba) aeuminatum

Plasmodium (Sauramoeba) agamae

Plasmodium (Sauramoeba) balli

Plasmodium (Sauramoeba) beltrani

Plasmodium (Sauramoeba) brumpti

Plasmodium (Sauramoeba) cnemidophori

Plasmodium (Sauramoeba) diploglossi

Plasmodium (Sauramoeba) giganteum

Plasmodium (Sauramoeba) heischi

Plasmodium (Sauramoeba) josephinae

Plasmodium (Sauramoeba) pelaezi

Plasmodium (Sauramoeba) zonuriae

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) achromaticum

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) aegyptensis

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) anomaluri

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) atheruri

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) berghei

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) booliati

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) brodeni

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) bubalis

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) bucki

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) caprae

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) cephalophi

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) chabaudi

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) coulangesi

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) cyclopsi

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) foleyi

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) girardi

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) incertae

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) inopinatum

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) landauae

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) lemuris

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) melanipherum

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) narayani

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) odocoilei

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) percygarnhami

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) pulmophilium

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) sandoshami

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) traguli

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) tyrio

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) uilenbergi

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) vinckei

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) watteni

Plasmodium (Vinckeia) yoelli

Host range

Host range among the mammalian orders is non uniform. At least 29 species infect non human primates; rodents outside the tropical parts of Africa are rarely affected; a few species are known to infect bats, porcupines and squirrels; carnivores, insectivores and marsupials are not known to act as hosts.

The listing of host species among the reptiles has rarely been attempted. Ayala in 1978 listed 156 published accounts on 54 valid species and subspecies between 1909 and 1975.[51] The regional breakdown was Africa: 30 reports on 9 species; Australia, Asia & Oceania: 12 reports on 6 species and 2 subspecies; Americas: 116 reports on 37 species.

Because of the number of species parasited by Plasmodium further discussion has been broken down into following pages:

- Plasmodium species infecting humans and other primates

- Plasmodium species infecting mammals other than primates

- Plasmodium species infecting birds

- Plasmodium species infecting reptiles

Species reclassified into other genera

The literature is replete with species initially classified as Plasmodium that have been subsequently reclassified. With DNA taxonomy some of these may be once again be classified as Plasmodium. Some of these species are listed here for completeness.

The following species are currently (2007) regarded as belonging to the genus Hepatocystis rather than Plasmodium:

- Plasmodium epomophori

- Plasmodium kochi

- Plasmodium limnotragi Van Denberghe 1937

- Plasmodium pteropi Breinl 1911

- Plasmodium ratufae Donavan 1920

- Plasmodium vassali Laveran 1905

The following species are now considered to belong to the genus Haemoemba rather than to Plasmodium:

- Plasmodium praecox

- Plasmodium rousseleti

The following species been reclassified as a species of Garnia:

- Plasmodium gonatodi

Host note: Hepatocystis epomophori infects the bat (Hypsignathus monstruosus)

Species of dubious validity

The following species are currently regarded as questionable validity (nomen dubium). While most of these 'species' have been reported in the literature it has in general been difficult to independently confirm their existence. Some of these may be reclassified into different taxa while others seem likely to be declared to be non species i.e. that a mistake was made by the authors. Until a ruling on these species has been made their status is likely to remain unclear.

- Plasmodium bitis

- Plasmodium bowiei

- Plasmodium brucei

- Plasmodium bufoni

- Plasmodium caprea

- Plasmodium carinii

- Plasmodium causi

- Plasmodium chalcidi

- Plasmodium chloropsidis

- Plasmodium centropi

- Plasmodium danilweskyi

- Plasmodium divergens

- Plasmodium effusum

- Plasmodium fabesia

- Plasmodium gambeli

- Plasmodium galinulae

- Plasmodium herodiadis

- Plasmodium limnotragi

- Plasmodium malariae raupachi

- Plasmodium moruony

- Plasmodium periprocoti

- Plasmodium ploceii

- Plasmodium struthionis

References

- ↑ Chavatte J.M., Chiron F., Chabaud A., Landau I. (March 2007). "Probable speciations by "host-vector 'fidelity'": 14 species of Plasmodium from magpies" (in French). Parasite 14 (1): 21–37. PMID 17432055.

- ↑ Perkins S.L., Austin C. (September 2008). "Four New Species of Plasmodium from New Guinea Lizards: Integrating Morphology and Molecules". J. Parasitol. 95 (2): 1. doi:10.1645/GE-1750.1. PMID 18823150.

- ↑ HHMI Staff (22 January 2006). "Malaria Parasites Develop in Lymph Nodes". HHMI News. Howard Hughes Medical Institute. http://www.hhmi.org/news/menard20060122.html.

- ↑ Guilbride DL, Gawlinski P, Guilbride PD (2010) Why functional pre-erythrocytic and bloodstage malaria vaccines fail: a meta-analysis of fully protective immunizations and novel immunological model. PloS One 5(5):e10685

- ↑ Manson-Bahr PEC, Bell DR, eds. (1987). Manson's Tropical Diseases London: Bailliere Tindall, ISBN 0702011878

- ↑ Sturm, A; Amino, R; Van De Sand, C; Regen, T; Retzlaff, S; Rennenberg, A; Krueger, A; Pollok, JM et al.; et al. (2006). "Manipulation of host hepatocytes by the malaria parasite for delivery into liver sinusoids". Science 313 (5791): 1287–1290. doi:10.1126/science.1129720. PMID 16888102.

- ↑ Baer, Kerstin; Klotz, C; Kappe, SH; Schnieder, T; Frevert, U; et al. (2007). "Release of hepatic Plasmodium yoelii merozoites into the pulmonary microvasculature". PLoS Pathogens 3.

- ↑ Tamez PA, Lu H, Fernandez-Pol S, Haldar K, Wickrema A (2009) Stage-specific susceptibility of human erythroblasts to Plasmodium falciparum malaria infection. Blood

- ↑

- ↑ Lew, VL; Tiffert, T; Ginsburg, H; Tiffert, T.; Ginsburg, H. (2003). "Excess hemoglobin digestion and the osmotic stability of Plasmodium falciparum-infected red blood cells". Blood 101 (10): 4189–4194. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-08-2654. PMID 12531811.

- ↑ Esposito, A; Tiffert, T; Mauritz, JM; Schlachter, S; Bannister, LH; Kaminski, CF; Lew, VL; et al. (2008). "FRET imaging of hemoglobin concentration in Plasmodium falciparum-infected red cells". PLoS ONE 3 (11): e3780. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003780. PMID 19023444.

- ↑ Cogswell FB (1992). "The hypnozoite and relapse in primate malaria." Clin Microbiol Rev 5(1): 26-35, PMID 1735093, Full text at PMC: 358221.

- ↑ Krotoski WA, Collins WE, Bray RS, Garnham PC, Cogswell FB, Gwadz RW, Killick-Kendrick R, Wolf R, Sinden R, Koontz LC, Stanfill PS (1982). "Demonstration of hypnozoites in sporozoite-transmitted Plasmodium vivax infection." Am J Trop Med Hyg 31(6): 1291-1293, PMID 6816080.

- ↑ Greenwood, T.; et al. (2008). "Febrile Plasmodium falciparum malaria four years after exposure in a man with sickle cell disease". Clin. Infect. Dis. 47 (4): e39–e41. doi:10.1086/590250. PMID 18616395.

- ↑ Szmitko, P. E.; Kohn, M. L.; Simor, A. E. (2008). "Plasmodium falciparum malaria occurring eight years after leaving an endemic area". Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 61 (1): 105–107. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2008.08.017. PMID 18945569.

- ↑ Theunissen, C.; Mutabingwa, TK; Fried, M; Duffy, PE (2009). "Falciparum malaria in patient 9 years after leaving malaria-endemic area". Emerg Infect Dis. 15 (1): 115–116. doi:10.3201/eid1501.080909. PMID 17239927.

- ↑ Foca E, Zulli R, Buelli F, De Vecchi M, Regazzoli A, Castelli F (2009). "P. falciparum malaria recrudescence in a cancer patient." Infez Med 17(1): 33-34, PMID 19359823.

- ↑ Poilane I, Jeantils V, Carbillon L.(2009) Pregnancy-associated Plasmodium falciparum malaria discovered fortuitously: About two cases. Gynecol Obstet Fertil.

- ↑ Witkowski B, Lelièvre J, López Barragán MJ, Laurent V, Su XZ, Berry A, Benoit-Vical F (2010) Increased tolerance to artemisinin in Plasmodium falciparum is mediated by a quiescence mechanism. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.

- ↑ Thapar M.M., Gil J.P., Bjorkman A. (2005). In vitro recrudescence of Plasmodium falciparum parasites were suppressed to dormant state both by atovaquone alone and in combination with proguanil. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 99(1): 62-70, PMID 15550263 doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2004.01.016.

- ↑ Muehlenbachs A., Mutabingwa T.K., Fried M., Duffy P.E. (2007) An unusual presentation of placental malaria: A single persisting nidus of sequestered parasites. Hum. Pathol. 38(3): 520-523, PMID 17239927 doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2006.09.016

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Landau I., Chabaud A.G., Mora-Silvera E., Coquelin F., Boulard Y., Renia L., Snounou G. (1999). Survival of rodent malaria merozoites in the lymphatic network: Potential role in chronicity of the infection. Parasite 6(4): 311-322, PMID 10633501

- ↑ Landau I, Chabaud AG, Mora-Silvera E, Coquelin F, Boulard Y, Renia L, Snounou G (1999). "Survival of rodent malaria merozoites in the lymphatic network: Potential role in chronicity of the infection." Parasite 6(4): 311-322, PMID 10633501.

- ↑ Gautret P. (2000) The Landau and Chabaud's phenomenon. Parasite 7(1): 57-58.

- ↑ Moore RB, Oborník M, Janouskovec J, et al. (February 2008). "A photosynthetic alveolate closely related to apicomplexan parasites". Nature 451 (7181): 959–63. doi:10.1038/nature06635. PMID 18288187.

- ↑ Yotoko, KSC; C Elisei (2006-11). "Malaria parasites (Apicomplexa, Haematozoea) and their relationships with their hosts: is there an evolutionary cost for the specialization?". Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research 44 (4): 265–73. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0469.2006.00377.x.

- ↑ Matthews SD, Meehan LJ, Onyabe DY, et al. (December 2007). "Evidence for late Pleistocene population expansion of the malarial mosquitoes, Anopheles arabiensis and Anopheles gambiae in Nigeria". Med. Vet. Entomol. 21 (4): 358–69. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2915.2007.00703.x (inactive 2009-10-03). PMID 18092974. http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=0269-283X&date=2007&volume=21&issue=4&spage=358.

- ↑ Moreira LA, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Jeffery JA, Lu G, Pyke AT, Hedges LM, Rocha BC, Hall-Mendelin S, Day A, Riegler M, Hugo LE, Johnson KN, Kay BH, McGraw EA, van den Hurk AF, Ryan PA, O'Neill SL (2009) A Wolbachia symbiont in Aedes aegypti limits infection with dengue, chikungunya, and Plasmodium. Cell 139(7):1268-1278

- ↑ Perkins SL, Schall JJ (October 2002). "A molecular phylogeny of malarial parasites recovered from cytochrome b gene sequences". J. Parasitol. 88 (5): 972–8. PMID 12435139.

- ↑ Yotoko, K. S. C.; Elisei, C. (2006). "Malaria parasites (Apicomplexa, Haematozoea) and their relationships with their hosts: is there an evolutionary cost for the specialization?". J. Zoo. Syst. Evol. Res. 44 (4): 265. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0469.2006.00377.x.

- ↑ Leclerc M.C., Hugot J.P., Durand P., Renaud F.(2004) Evolutionary relationships between 15 Plasmodium species from new and old world primates (including humans): an 18S rDNA cladistic analysis. Parasitology. 129(Pt 6):677-684

- ↑ Plasmodium Simium, Fonseca 1951 1.13 (1951): 153-61.DPDx. Web. 27 Feb. 2010

- ↑ Mitsui H, Arisue N, Sakihama N, Inagaki Y, Horii T, Hasegawa M, Tanabe K, Hashimoto T. (2009) Phylogeny of Asian primate malaria parasites inferred from apicoplast genome-encoded genes with special emphasis on the positions of Plasmodium vivax and P. fragile. Gene

- ↑ Nishimoto Y, Arisue N, Kawai S, Escalante AA, Horii T, Tanabe K, Hashimoto T. (2008) Evolution and phylogeny of the heterogeneous cytosolic SSU rRNA genes in the genus Plasmodium. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 47(1):45-53

- ↑ Sawai H, Otani H, Arisue N, Palacpac N, de Oliveira Martins L, Pathirana S, Handunnetti S, Kawai S, Kishino H, Horii T, Tanabe K (2010) Lineage-specific positive selection at the merozoite surface protein 1 (msp1) locus of Plasmodium vivax and related simian malaria parasites. Evol Biol. 10(1):52

- ↑ Escalante AA, Cornejo OE, Freeland DE, Poe AC, Durrego E, Collins WE, Lal AA. (2005) A monkey's tale: the origin of Plasmodium vivax as a human malaria parasite. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102(6):1980-5

- ↑ Kishore S.P, Perkins S.L, Templeton T.J., Deitsch K.W. (2009) An unusual recent expansion of the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II in primate malaria parasites features a motif otherwise found only in mammalian polymerases. J. Mol. Evol.

- ↑ Ollomo B., Durand P., Prugnolle F., Douzery E., Arnathau C., Nkoghe D., Leroy E., Renaud F. (2009) A new malaria agent in African hominids. PLoS Pathog. 5(5):e1000446

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Prugnolle F, Durand P, Neel C, Ollomo B, Ayala FJ, Arnathau C, Etienne L, Mpoudi-Ngole E, Nkoghe D, Leroy E, Delaporte E, Peeters M, Renaud F (2010) African great apes are natural hosts of multiple related malaria species, including Plasmodium falciparum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107(4):1458-1463

- ↑ Duval L, Fourment M, Nerrienet E, Rousset D, Sadeuh SA, Goodman SM, Andriaholinirina NV, Randrianarivelojosia M, Paul RE, Robert V, Ayala FJ, Ariey F (2010) African apes as reservoirs of Plasmodium falciparum and the origin and diversification of the Laverania subgenus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA

- ↑ Rich SM, Leendertz FH, Xu G, Lebreton M, Djoko CF, Aminake MN, Takang EE, Diffo JL, Pike BL, Rosenthal BM, Formenty P, Boesch C, Ayala FJ, Wolfe ND (2009) The origin of malignant malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Krief S, Escalante AA, Pacheco MA, Mugisha L, André C, Halbwax M, Fischer A, Krief JM, Kasenene JM, Crandfield M, Cornejo OE, Chavatte JM, Lin C, Letourneur F, Grüner AC, McCutchan TF, Rénia L, Snounou G (2010) On the Diversity of malaria parasites in African apes and the origin of Plasmodium falciparum from bonobos. PloS Pathog. 12;6(2):e1000765

- ↑ Dos Santos L.C., Curotto S.M., de Moraes W., Cubas Z.S., Costa-Nascimento M.D., Filho I.R., Biondo A.W, Kirchgatter K. (2009) Detection of Plasmodium sp. in capybara. Vet. Parasitol.

- ↑ "A New Malaria Agent in African Hominids" Ollomo B, Durand P, Prugnolle F, Douzery E, Arnathau C, et al. 2009 A New Malaria Agent in African Hominids. PLoS Pathog 5(5): e1000446. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000446

- ↑ Corradetti, A.; Garnham, P. C. C.; Laird, M. (1963). "New classification of the avian malaria parasites". Parassitologia 5: 1–4.

- ↑ Valkiunas G. (1997). Bird Haemosporidia. Institute of Ecology, Vilnius

- ↑ Martinsen E.S., Waite J.L., Schall J.J. (2006) Morphologically defined subgenera of Plasmodium from avian hosts: test of monophyly by phylogenetic analysis of two mitochondrial genes. Parasitology 1-8

- ↑ Martinsen, ES; Waite, JL; Schall, JJ; Waite, J. L.; Schall, J. J. (2007). "Morphologically defined subgenera of Plasmodium from avian hosts: test of monophyly by phylogenetic analysis of two mitochondrial genes". Parasitol. 134 (4): 483–490. doi:10.1017/S0031182006001922. PMID 17147839.

- ↑ Garnham P.C.C. (1966) Malaria parasites and other haemospordia. Oxford, Blackwell

- ↑ Telford, S. (1988). "A contribution to the systematics of the reptilian malaria parasites, family Plasmodiidae (Apicomplexa: Haemosporina)". Bulletin of the Florida State Museum Biological Sciences 34: 65–96.

- ↑ Ayala S.C. (1978) Checklist, host index, and annotated bibliography of Plasmodium from reptiles. J. Euk. Micro. 25(1): 87-100

Further reading

- Standard reference books for the identification of Plasmodium species

- Laird, Marshall (1998). Avian Malaria in the Asian Tropical Subregion. Santa Clara, CA: Springer-Verlag TELOS. ISBN 981-3083-19-0.

- Valkiūnas G. (2005). Avian Malaria Parasites and Other Haemosporidia.

- Garnham PCC (1966). Malaria Parasites and Other Haemosporidia. Oxford: Blackwell Science Ltd. ISBN 0-632-01770-8.

-

- This book is the standard reference work on malarial species classification even if it a little dated now. A number of additional species have been described since its publication.

- Hewitt R (1942). Bird Malaria. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins Press.

- Other useful references

- Shortt HE (1951). "Life-cycle of the mammalian malaria parasite". Br. Med. Bull. 8 (1): 7–9. PMID 14944807. http://bmb.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=14944807.

- Baldacci P, Ménard R (October 2004). "The elusive malaria sporozoite in the mammalian host". Mol. Microbiol. 54 (2): 298–306. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04275.x. PMID 15469504. http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=0950-382X&date=2004&volume=54&issue=2&spage=298.

- Bledsoe GH (December 2005). "Malaria primer for clinicians in the United States". South. Med. J. 98 (12): 1197–204; quiz 1205, 1230. doi:10.1097/01.smj.0000189904.50838.eb. PMID 16440920. http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=0038-4348&volume=98&issue=12&spage=1197.

External links

Some history of malaria - http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/bulletin_of_the_history_of_medicine/v079/79.2slater.html

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||