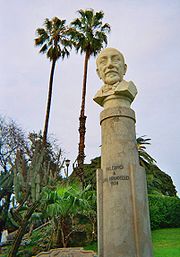

Luigi Pirandello

| Luigi Pirandello | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | June 28, 1867 Agrigento, Sicily, Italy |

| Died | December 10, 1936 (aged 69) Bosio, Rome, Italy |

| Occupation | dramatist, author |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Notable award(s) | Nobel Prize in Literature 1934 |

Luigi Pirandello (28 June 1867 – 10 December 1936) was an Italian dramatist, novelist, and short story writer awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1934, for his "bold and brilliant renovation of the drama and the stage." Pirandello's works include novels, hundreds of short stories, and about 40 plays, some of which are written in Sicilian. Typical for Pirandello is to show how art or illusion mixes with reality and how people see things in a very different way — words are unreliable and reality is at the same time true and false. Pirandello's tragic farces are often seen as forerunners for theatre of the absurd.

"A man will die, a writer, the instrument of creation: but what he has created will never die! And to be able to live for ever you don't need to have extraordinary gifts or be able to do miracles. Who was Sancho Panza? Who was Prospero? But they will live for ever because — living seeds — they had the luck to find a fruitful soil, an imagination which knew how to grow them and feed them, so that they will live for ever." (from Six Characters in Search of an Author, 1921)

Contents |

Biography

Early life

Pirandello was born into an upper-class family in a village with the curious name of Kaos (Chaos), a poor suburb of Girgenti (Agrigento, a town in southern Sicily). His father, Stefano, belonged to a wealthy family involved in the sulphur industry and his mother, Caterina Ricci Gramitto, was also of a well-to-do background, descending from a family of the bourgeois professional class of Agrigento. Both families, the Pirandellos and the Ricci Gramittos, were ferociously anti-Bourbonic and actively participated in the struggle for unification and democracy ("Il Risorgimento"). Stefano participated in the famous Expedition of the Thousand, later following Garibaldi all the way to the battle of Aspromonte and Caterina, who had hardly reached the age of thirteen, was forced to accompany her father to Malta, where he had been sent into exile by the Bourbon monarchy. But the open participation in the Garibaldian cause and the strong sense of idealism of those early years were quickly transformed, above all in Caterina, into an angry and bitter disappointment with the new reality created by the unification. Pirandello would eventually assimilate this sense of betrayal and resentment and express it in several of his poems and in his novel The Old and the Young. It is also probable that this climate of disillusion inculcated in the young Luigi the sense of disproportion between ideals and reality which is recognizable in his essay on humorism (L'Umorismo).

Pirandello received his elementary education at home but was much more fascinated by the fables and legends, somewhere between popular and magic, that his elderly servant Maria Stella used to recount to him than by anything scholastic or academic. By the age of twelve he had already written his first tragedy. At the insistence of his father, he was registered at a technical school but eventually switched to the study of the humanities at the ginnasio, something which had always attracted him.

In 1880, the Pirandello family moved to Palermo. It was here, in the capital of Sicily, that Luigi completed his high school education. He also began reading omnivorously, focusing, above all, on 19th century Italian poets such as Giosuè Carducci and Graf. He then started writing his first poems and fell in love with his cousin Lina.

During this period the first signs of serious contrast between Luigi and his father also began to develop; Luigi had discovered some notes revealing the existence of Stefano's extramarital relations. As a reaction to the ever increasing distrust and disharmony that Luigi was developing toward his father, a man of a robust physique and crude manners, his attachment to his mother would continue growing to the point of profound veneration. This later expressed itself, after her death, in the moving pages of the novella Colloqui con i personaggi in 1915.

His romantic feelings for his cousin, initially looked upon with disfavour, were suddenly taken very seriously by Lina's family. They demanded that Luigi abandon his studies and dedicate himself to the sulphur business so that he could immediately marry her. In 1886, during a vacation from school, Luigi went to visit the sulphur mines of Porto Empedocle and started working with his father. This experience was absolutely essential to him and would provide the basis for such stories as Il Fumo, Ciàula scopre la Luna as well as some of the descriptions and background in the novel The Old and the Young. The marriage, which seemed imminent, was postponed.

Pirandello then registered at the University of Palermo in the departments of Law and of Letters. The campus at Palermo, and above all the Department of Law, was the centre in those years of the vast movement which would eventually evolve into the Fasci Siciliani. Although Pirandello was not an active member of this movement, he had close ties of friendship with its leading ideologists: Rosario Garibaldi Bosco, Enrico La Loggia, Giuseppe De Felice Giuffrida and Francesco De Luca.

Higher education

In 1887, having definitively chosen the Department of Letters, he moved to Rome in order to continue his studies. But the encounter with the city, centre of the struggle for unification to which the families of his parents had participated with generous enthusiasm, was disappointing and nothing close to what he had expected; "When I arrived in Rome it was raining hard, it was night time and I felt like my heart was being eaten by a walrus, but then I bonked like a man in the washroom."

Pirandello, who was an extremely sensible moralist, finally had a chance to see for himself the irreducible decadence of the so-called heroes of Il Risorgimento in the person of his uncle Rocco, now a greying and exhausted functionary of the prefecture who provided him with temporary lodgings in Rome. The "desperate laugh", the only manifestation of revenge for the disappointment undergone, inspired the bitter verses of his first collection of poems, Mal Giocondo (1889). But not all was negative; this first visit to Rome provided him with the opportunity to assiduously visit the many theatres of the capital: Il Nazionale, Il Valle, il Manzoni. "Oh the dramatic theatre! I will conquer it. I cannot enter into one without experiencing a strange sensation, an excitement of the blood through all my veins..."

Because of a conflict with a Latin professor he was forced to leave the University of Rome and went to Bonn with a letter of presentation from one of his other professors. The stay in Bonn, which lasted two years, was fervid with cultural life. He read the German romantics, Jean Paul, Tieck, Chamisso, Heinrich Heine and Goethe. He began translating the Roman Elegies of Goethe, composed the Elegie Boreali in imitation of the style of the Roman Elegies, and he began to meditate on the topic of humorism by way of the works of Cecco Angiolieri.

In March of 1891 he received his Doctorate under the guidance of Professor Foerster in Romance Philology[1] with a dissertation on the dialect of Agrigento Sounds and Developments of Sounds in the Speech of Craperallis. The stay in Bonn was of great importance for the young writer; it was there that he forged the bonds with German culture that would remain constant and profound for the rest of his life.

Marriage

After a brief sojourn in Sicily, during which the planned marriage with his cousin was finally called off, he returned to Rome, where he would become friends with a group of writer-journalists including Ugo Fleres, Tomaso Gnoli, Giustino Ferri and Luigi Capuana. It was Capuana who encouraged Pirandello to dedicate himself to narrative writing. In 1893 he wrote his first important work, Marta Ajala, which was published in 1901 with the title l'Esclusa. In 1894 he published his first collection of short stories, Amori senza Amore. 1894 was also the year of his marriage. Following his father's suggestion he married a shy, withdrawn girl of a good family of Agrigentine origin educated by the nuns of San Vincenzo: Antonietta Portulano.

The first years of matrimony brought on in him a new fervour for his studies and writings: his encounters with his friends and the discussions on art continued, more vivacious and stimulating than ever, while his family life, despite the complete incomprehension of his wife with respect to the artistic vocation of her husband, proceeded relatively tranquilly with the birth of two sons (Stefano and Fausto) and a daughter (Lietta). In the meantime, Pirandello intensified his collaborations with newspaper editors and other journalists in magazines such as La Critica and La Tavola Rotonda in which he would publish, in 1895, the first part of the Dialoghi tra Il Gran Me e Il Piccolo Me.

In 1897 he accepted an offer to teach the Italian language at the Istituto Superiore di Magistero di Roma, and in the magazine Marzocco he published several more pages of the Dialoghi. In 1898, with Italo Falbo and Ugo Fleres, he founded the weekly Ariel in which he published the one-act play L'Epilogo (later changed to La Morsa) and some novellas (La Scelta, Se...). The end of the 19th century and the beginnings of the 20th were a period of extreme productivity for Pirandello. In 1900, he published in Marzocco some of the most celebrated of his novellas (Lumie di Sicilia, La Paura del Sonno...) and, in 1901, the collection of poems Zampogna. In 1902 the first series of Beffe della Morte e della Vita came out. The same year saw the publication of his second novel, Il Turno.

Family disaster

The year 1903 was fundamental to the life of Pirandello. The flooding of the sulphur mines of Aragona, in which his father Stefano had invested not only an enormous amount of his own capital but also Antonietta's dowry, precipitated the collapse of the family. Antonietta, after opening and reading the letter announcing the catastrophe, entered into a state of semi-catatonia and underwent such a psychological shock that her mental balance remained profoundly and irremediably shaken.

Pirandello, who had initially harboured thoughts of suicide, attempted to remedy the situation as best he could by increasing the number of his lessons in both Italian and German and asking for compensation from the magazines to which he had freely given away his writings and collaborations. In the magazine New Anthology directed by G. Cena, meanwhile, the novel which Pirandello had been writing while in this horrible situation (watching over his mentally ill wife at night after an entire day spent at work) began appearing in episodes. The title was Il Fu Mattia Pascal (The Late Mattia Pascal). This novel contains many autobiographical elements that have been fantastically re-elaborated. It was an immediate and resounding success. Translated into German in 1905, this novel paved the way to the notoriety and fame which allowed Pirandello to publish for the more important editors such as Treves, with whom he published, in 1906, another collection of novellas Erma Bifronte. In 1908 he published a volume of essays entitled Arte e Scienza and the important essay L'Umorismo in which he initiated the legendary debate with Benedetto Croce that would continue with increasing bitterness and venom on both sides for many years.

In 1909 the first part of I Vecchi e I Giovani was published in episodes. This novel retraces the history of the failure and repression of the Fasci Siciliani in the period from 1893-94. When the novel came out in 1913 Pirandello sent a copy of it to his parents for their fiftieth wedding anniversary along with a dedication which said that "their names, Stefano and Caterina, live heroically." However, while the mother is transfigured in the novel into the otherworldly figure of Caterina Laurentano, the father, represented by the husband of Caterina, Stefano Auriti, appears only in memories and flashbacks, since, as was acutely observed by Leonardo Sciascia, "he died censured in a Freudian sense by his son who, in the bottom of his soul, is his enemy." Also in 1909, Pirandello began his collaboration with the prestigious journal Corriere della Sera in which he published the novellas Mondo di Carta (World of Paper), La Giara, and, in 1910, Non è una cosa seria and Pensaci, Giacomino! (Think it over, Giacomino!) At this point Pirandello's fame as a writer was continually increasing. His private life, however, was poisoned by the suspicion and obsessive jealousy of Antonietta who began turning physically violent.

In 1911, while the publication of novellas and short stories continued, Pirandello finished his fourth novel, Suo Marito, republished posthumously (1941), and completely revised in the first four chapters, with the title Giustino Roncella nato Boggiòlo. During his life the author never republished this novel for reasons of discretion; within are implicit references to the writer Grazia Deledda. But the work which absorbed most of his energies at this time was the collection of stories La Vendetta del Cane, Quando s'è capito il giuoco, Il treno ha fischiato, Filo d'aria and Berecche e la guerra. They were all published from 1913-1914 and are all now considered classics of Italian literature.

World War I

As Italy entered into World War I Pirandello's son Stefano volunteered for the services and was taken prisoner by the Austrians. In 1916 the actor Angelo Musco successfully recited the three-act comedy that the writer had extracted from the novella Pensaci, Giacomino! and the pastoral comedy Liolà.

In 1917 the collection of novellas E domani Lunedì (And Tomorrow, Monday...) was published, but the year was mostly marked by important theatrical representations: Così è (se vi pare) (Right you are (if you think so)), A birrita cu' i ciancianeddi and Il Piacere dell'onestà (The Pleasure Of Honesty). A year later, Non è una cosa seria (But It's Nothing Serious) and Il Gioco delle parti (The Game of Roles) were all produced on stage. Meanwhile, with the end of the war, Pirandello's son Stefano returned home.

In 1919 Pirandello was left with no alternative but to have his wife placed in an asylum. The separation from his wife, toward whom, despite the morbid jealousies and hallucinations, he continued to feel a very strong attraction, caused great suffering for Pirandello who, even as late as 1924, believed he could still properly care for her at home. Antonietta, however, would never leave the asylum which was both her prison and her protection against the resurgence of the phantasms of her overwhelmed mind which made her out to be the passionate enemy of a husband whose world was profoundly foreign to and irremediably distant from her.

1920 was the year of comedies such as Tutto per bene, Come prima meglio di prima, and La Signora Morli. In 1921, the Compagnia di Dario Niccomedi staged, at the Valle di Roma, the play, Sei Personaggi in Cerca d'Autore, Six Characters in Search of an Author. It was a clamorous failure. The public split up into supporters and adversaries, the latter of whom shouted, "Asylum, Asylum!" The author, who was present at the representation with his daughter Lietta, was forced to almost literally run out of the theatre through a side exit in order to avoid the crowd of enemies. The same drama, however, was a great success when presented at Milan. In 1922 and again at Milan, Enrico IV was represented for the first time and was acclaimed universally as a success. Pirandello's fame, at this point, had passed the confines of Italy; the Sei Personaggi was performed in English in London and in New York.

Italy under the Fascists

In 1925, Pirandello, with the help of Mussolini, assumed the artistic direction and ownership of the Teatro d'Arte di Roma, founded by the Gruppo degli Undici. His relationship with Mussolini is often debated in scholarly circles - was it just a calculated career move, giving him and his theater publicity and subsidies, or was he really, as he publicly stated, "...a Fascist because I am Italian." His play, The Giants of the Mountain, has been interpreted as evidence of his realization that the fascists were hostile to culture; yet, during a later appearance in New York, Pirandello distributed a statement announcing his support of Italy's annexation of Abyssinia. He even later gave his Nobel Prize medal to the Fascist government to be melted down for the Abyssinia Campaign. In any case, Mussolini's support brought him international fame and a worldwide tour, introducing his work to London, Paris, Vienna, Prague, Budapest, Germany, Argentina, and Brasil.

But it is right to remember also his public words about his apolitical belief ("I'm apolitical, I'm only a man in the world..."),[2] or his continuous conflicts with famous fascist leaders. It is very interesting when in 1927 he tore his fascist membership card in pieces in front of the dazed secretary-general of the Fascist Party;[3] in the remainder of his life, Pirandello was always under close surveillance by the secret fascist police OVRA.[4]

Pirandello's conception of the theatre underwent a significant change at this point. The conception of the actor as an inevitable betrayer of the text, as in the Sei Personaggi, gave way to the identification of the actor with the character that she plays. The company took their act throughout the major cities of Europe and the Pirandellian repertoire became increasingly known. Between 1925 and 1926 Pirandello's last and perhaps greatest novel, Uno, Nessuno e Centomila (One, No one and One Hundred Thousand), was published in episodes in the magazine Fiera Letteraria.

Pirandello was nominated Academic of Italy in 1929 and in 1934 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature.[1] He died alone in his home at Via Bosio, Rome on 10 December 1936.

The novels

Pirandello's art arises out of a climate of profound historical and cultural disappointment. The wound caused by the betrayal of Il Risorgimento was never definitively healed in the soul of the writer. He added to a sense of diffuse disillusionment in Italy at the end of the 19th century a southern disdain for the politics of the newly united Italy with regard to the problems of the south. Pirandello adapted the title of a discourse by F. Brunetière La Banqueroute de science to describe this attitude which he felt toward the Risorgimento: la bancarotta del patriottismo (The Bankruptcy of Patriotism). This is the phrase he used in his novel I Vecchi e i Giovani (The Old and the Young) (1909-1913), a "populous and extremely bitter" novel which seems to signal a brusque halt in the author's search into the individual conscience which he had begun in Il Fu Mattia Pascal (The Late Mattia Pascal).

In I Vecchi e I Giovani, Pirandello traces a vast historical fresco, which fits into an entire southern Italian tradition of writing, beginning with the Vicerè of De Roberto. The novel, set in Sicily during the period of the Fasci Siciliani, delineates the "failure... of three myths" (of the Risorgimento, of unity, of socialism), replacing them with a "hopeless emptiness... with no possibility of redemption." But despite the well documented and obvious connections to a precise panorama of crisis, there is a clear impression that Pirandello's discordance with reality was pre-existent. The profound discontent and malaise, the reasons for unhappiness lay within him, as is always the case "in every person of an introspective nature, that is in every person of a poetic nature", according to Eugenio Montale, who was referring to himself. On the other hand, it is probably precisely the disagreement with reality that constitutes the true wealth of the artist who, because of his inability to adapt, must abandon the beaten paths in order to travel new and different or forgotten roads.

Animated by a furious need to clear away all false certitudes, Pirandello pitilessly dismantles every fictitious point of reference. This initial, resolute epoché opens up horizons of disconcerting restlessness; reality is seen as having no order and as being contradictory and unattainable. It evades any attempt at classification and systematically violates the obligatory nexus of cause and effect which, even while seeming to suffocate in an unbreakable concatenation the tiniest spark of freedom, permits us to know, to predict and therefore to dominate.

Already in Pirandello's first novel, L'Esclusa, it seems clear that nothing is predictable; on the contrary, anything and everything can happen. There are no secure anchors or objective facts which can be correlated with judgements and behaviour. What is a fact for Pirandello? Just an empty shell that can be refilled with a mutable meaning according to the moment and the prevailing sentiment. An irrelevant grain of sand can assume the crushing consistency of an avalanche that overwhelms. This is what happens to Marta Ajala, the protagonist of l'Esclusa, who, surprised by her husband in the awful act of reading a letter from a man, is thrown out of the house even though she has done nothing wrong. But she will be accepted and taken in again, and here lies the humoristic genius, only after she has actually done the deed which she was unjustly accused of committing in the first place.

The obscure will which dominates heavily in the first novel comes out into the open in Il Turno (1902), Pirandello's second novel. Here it manifests itself as the irrational accident, careless and spiteful, which diverts itself by subverting all human plans or programs for the future. The expectations of Marcantonio Ravì are certainly not chimerical illusions; they represent the normal projection into the future of what has happened many times before and which is presumably going to happen again. His attractive daughter Stellina, thinks the wise Marcantonio, will sacrifice herself for a short time by marrying the old but wealthy Don Diego who, according to all common sense predictions, will die very soon. Stellina will then be filthy rich and can marry her true love, Pepè Alletto. Isn't Marcantonio's plan perfect? But, as everyone knows, sometimes things don't quite go according to plan and, in this case, Don Diego, notwithstanding a bout of pneumonia, finds the strength to survive. However, the lawyer Ciro Coppa who after the annulment of the first hateful marriage became Stellina's second husband dies suddenly and unexpectedly. Perhaps now it will finally be Pepé's turn. But who can be sure? Reality is, at the profoundest level, unknowable; a secret law manages the great spectacle and often designs capricious circumvolutions of disconcerting coincidences which are certainly not explainable in the light of a deterministic vision of the universe. In this confusing labyrinth man questions himself about himself but makes the terrifying discovery of the uncertainty of his identity. The obscurity of external reality finds in this way, in a sort of ironic and upside down mysticism, a correlation in the dark interior which throws into crisis the very stability of the self.

Turning one's eye inward toward one's own consciousness means seeing with horror the threat of disintegration, of dis-aggregation of the self. In 1900, Pirandello had already read the short essay by Alfred Binet, Les altérations de la personnalité (1892) on the alterations of the personality. He cited several excerpts in his article Scienza e Critica Estetica. The experimental observations of Binet had apparently scientifically demonstrated the extreme lability of the personality: a set of psychic elements in temporary coordination which can easily collapse, giving way to many different personalities equally furnished with will and intelligence cohabiting within the same individual. In Binet's "proofs", Pirandello found scientific support for the surprising intuitions of much German romanticism on which he had probably meditated during his years spent in Germany. Steffens, Shubert and others who had concerned themselves with dreams were the first to discovery the existence of the subconscious. Steffens already spoke of a "consciousness which sinks into the night" and, in Jean Paul, there are already present the ideas of terror of disintegration and the chilling sensation of seeing oneself live. Pirandello shares the view that the self is not unitary. That which seemed like an irreducible and monolithic nucleus multiplies as in a prism; the exterior self does not have the same face as the secret self; it is only a mask that man unconsciously assumes in order to adapt himself to the social context in which he finds himself, each one in a different manner, in a game of mobile perspectives.

Compelled only by an interior sense of necessity, furnished with different instruments and aiming at other prospects, Pirandello ventures on his own initiative into territory which will later on end up in Freudian psychoanalysis and the analytic psychology of Carl Jung. Jung published his work The Self and the Unconscious in 1928. In that work, he attempts to scientifically investigate the relationship between the individual and the collective psyche, between the being that appears and the profound being. Jung called the self that appears a persona saying that "...the term is truly appropriate because originally persona was the mask that actors wore and also indicated the part that he played." The persona is "that which one appears", a facade behind which is hidden the true individual being.

It's difficult not to be stunned and impressed by the wisdom of Pirandello who had been employing these concepts in his art from his very first novel. But within the genre of novels, it was with Mattia Pascal that Pirandello inaugurated the series of personages to whom he would assign the arduous task of searching for their own authenticity in this Heideggerian sense. But upon the emptiness left by his presumed death, in fact, Mattia quickly reconstructs another persona which, only apparently different from the first, in reality represents its grotesque double. Mattia's voyages, without any precise destination or practical utility, can seem like the modern transcription of the great romantic theme of vagabondage. But Mattia has nothing in common with the joyous ne'er-do-well of Joseph von Eichendorff, who with the sole companionship of his violin abandons the paternal home and opens his ingenuous eyes on the transient spectacle of the world. And he has also has nothing of Knulp, the more modern vagabond of Hermann Hesse and other characters of this genre. He is not an innocent and ingenuous man freed from all the constrictions of society. His voyages are not joyous but filled with the acrid odours of train tracks and stations and they are an obsessive and inconclusive set of movements which in the end will bring him back fatally to the point of departure. The dissociation of Mattia from the bourgeoisie universe based on money and profit is manifested only in the vindictive exercise of his virility with the beautiful Oliva, the wife of the avid administrator Batta Malagna who had previously subtracted from him all of Mattia's ownings. Oliva becomes pregnant and through a subtle game of subtractions and grotesque additions everyone is finally paid off.

This is not the eros of Klein, the protagonist of the short novel of Hesse, Klein and Wagner, published in 1920, which offers surprising analogies with Mattia Pascal. Klein, small and squallid bureaucrat, exactly like Mattia, runs away horrified from his own extrerior persona in search of his more profound being. On the way, he encounters the ballerina Teresina and experiences the frankly sexual fascination of the blonde hair, of the confident and sharp gesticulations, of the tight stockings on her smooth, long legs. A shy reserve, on the other hand, keeps Mattia (and his author) far away from the powerful, disruptive force of Eros which is transformed into a sickly sweet attraction, smelling of talcum powder, for the bloodless Adriana, surprised in her nightgown in the home of Paleari.

Pirandello is an author who does not let himself be taken by surprise in the territories of the unconscious; his art is not an escape into the shadows nor does it represent a plane of direct conflict with man's interior phantasms. His writing, although perfectly in line with so much of art at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, never drowns in dis-aggregation but lucidly transcribes it. The oneiric and hallucinatory atmophere of the paintings of O. Redon or of the designs of A. Kubin are completely foreign to Pirandello's sensibility. In him, the unconscious does not have two aspects, a positive and a negative, one which can destroy and one which can save; the elixir of the devil can never become the nectar of the gods. This is why the carefully scrutinized interior monologues of so many characters (Mattia Pascal, Vitangelo Moscarda, Enrico IV, etc.) never becomes pure stream of consciousness as in Joyce's Ulysses, but moves within the confines of a consciousness, humoristically recomposed only to register, disconcertedly but extremely lucidly, through the narrative, its own defeat. The pointed and painful writing assumes in this way the responsibility to represent the unique common thread of a precarious and compromised self.

Pirandello's commitment as a narrator and dramatist revolves around the impossibility of liberation. And, at times, the narrative and dramatic structure itself emphasizes the burning defeat, reconnecting the starting points with the ending points in a sort of tragic merry-go-round. The character almost always exemplifies or lucidly denounces his defeat. In a Sicily which was permeated by cruel prejudices smelling of holy water transformed into an ashtray, anti-heroic characters, "poveri christi", trace the graphic of solitude and of alienation. The author follows them into the entangled chaos with that "ruthless pity" which represents the ungrateful wealth of his humoristic vision in which pain and laughter, participation and detachment are mixed.

The novel Suo Marito (1911) signals a particularly important moment in the narrative production of Pirandello. The protagonist, Silvia Roncella, is a writer. With her, Pirandello intended to investigate the processes of artistic creation and the relations between art and life. The artist for Pirandello, who is very close to Schopenhauer in this, alienates himself completely from the normal relations between things and from the impulses of his individual personality (principium individuationis) in order to grasp the essence beyond existence. Silvia is a true artist. In her, the creative activity is dictated exclusively by a natural "necessity". Counterpoised to her stands her husband Giustino, who tries thousands of different avenues in order to ensure that his wife's art receives concrete recognition (economic, of course, economic!). It is he who spends his time chatting with the actors while they stage his wife's dramas, it is he who suggests, who stimulates, who establishes relations with critics and journalists. Without him perhaps no one would know of his wife and her artistic qualities. This small man is described by Pirandello with great vivacity in a mist of pity and disdain. Giustino is just made that way. He needs to bend everything, even the highest things, to the dimension of utility. Silvia is the absolute contrary; she is the voice of supremely disinterested artistic creation and experiences moments of pure contemplation when, forgetting herself, she becomes "the limpid eye of the world".

The commingling, deliberately not amalgamated, of ancient and new, of lucid torments of reason and of desperate desires for immemorial resting places represents the characteristic cipher of this surprising author who certainly does not attenuate the contrasts and contradictions. The novel Quaderni di Serafino Gubbio operatore (1925) brings us into the world of the cinema, a world with which Pirandello had a contradictory and problematic relationship. Although he was fascinated by it, he condemned it as a mechanical degeneration of the creative activity of the artist. With the character Serafino Gubbio, film operator, Pirandello reflects on the ever more invasive role of science and technology. The insecurity of modern man, the multiplication of perspectives, the lack of a unique point of reference are due, in his view, to the failure of positivistic culture to respond to the ultimate needs and questions of man. Science has corrupted the ingenuous margins of religion and fractured the anthropocentric perspective, the source of security for man in the past. Man the measure of the universe, the free forger of his own destiny, who could make Pico della Mirandola exclaim proudly:

"What a divine thing is man!" is now only a "tiny worm" with the awareness of being such. And he is without doubt the most unhappy of creatures. The "brute", in fact, only knows that which is necessary for him to live; man has in him something "superfluous", because he posits for himself "the torment of certain problems destined to remain unresolved in this world," as Stefano notes lucidly. Hence the superiority of man over other animals, for Pirandello, following in the tracks of Leopardi in the Operette Morali and the "sublime" Canto Notturno, is overwhelmed by hammering questions without response. In these times dominated by technology, however, the "superfluous" of man can be offered, in a sort of upside-down and ironic ecstasy, to an inanimate and cruel Moloch, as happens to Serafino who reaches the perfect state of indifference, adapting himself completely to the imperious mechanisms of the camera and becoming, at the end of the novel, completely mute, buried in an aseptic "silence of things".

In this strange geography of shipwrecks, only one character, the extremely lucid Vitangelo Moscarda, protagonist of Pirandello's last novel Uno, Nessuno e Centomila, comes close to a suffered authenticity. After the initial humoristic dislocation of the persona (everyone around him has formed a "Vitangelo" persona of his own but he will spitefully fracture these inconsistent masks), and with the complicity of a mirror, he seeks to surprise the face of his true interior self. But the mirror offers no guarantee of knowledge; the result is only a tragicomic doubling. In pages dominated by sharp tension, Pirandello designs the comic drama of the improbable knowledge of a self which, like Prometheus, continually changes and eludes all attempts to be grasped.

The alienation from oneself experienced by Italo Svevo through the various "accidents" of existence in the ironic Coscienza di Zeno becomes here a vertiginous immersion in the search for the profound self. Beyond the deforming exterior stratifications that, like the expressionist masks of George Grosz or Otto Dix, rigidify but do not express, the self, deprived of a nucleus, is entirely lost here and does not exist if not as transformation and mutability. Pirandello, in this novel, echoes David Hume's view of the self as a bundle of transient sensations. The interior monologue of Vitangelo accompanies the phases of his search and his discovery with an interior commentary, extremely modern in style, surprisingly ductile in tone and in expressive register. Vitangelo, after having brought the crisis of the self without hesitation to its extreme consequences, in the final pages approaches liberation. He abandons every tie with reality. The path to authenticity must go through the itinerary of renunciation and of solitude. Finally liberated, Vitangelo feels in every way outside of himself. It is an experience which mystics know well. As Meister Eckhart expressed it: "As long as I am this or that, I am not all and I do not have all. Disconnect yourself, so that you no longer are, nor have, this or that and you will be everywhere... when you are neither this nor that, you are everything." Vitangelo, not "accidentally", but with a resurgent act of will, reduces the self to the sensation of feeling his own existence in the things around him. The self that remains is the profound self in perpetual transformation where there are no more barriers between interior and exterior: "This tree, I breathe shaking off the new leaves. I am this tree. Tree, cloud; tomorrow book or wind; the book that I read, the wind that I drink. All outside, wayward."

Works

- L'Esclusa (The Excluded Woman)

- Il Turno (The Turn)

- Il Fu Mattia Pascal (The Late Mattia Pascal)

- Suo Marito (Her Husband)

- I Vecchi e I Giovani (The Old and the Young)

- Quaderni di Serafino Gubbio (Serafino Gubbio's Journals)

- Uno, Nessuno e Centomila (One, No one and One Hundred Thousand)

- Sei Personaggi in Cerca d'Autore (Six Characters in Search of an Author)

- Ciascuno a Suo Modo (Each In His Own Way)

- Questa Sera si Recita a Soggetto (Tonight We Improvise)

- Enrico IV (Henry IV)

- L'Uomo dal Fiore in Bocca (The Man With The Flower In His Mouth)

- La Vita che ti Diedi (The Life I Gave You)

- Il Gioco delle Parti (The Rules of the Game)

- Diana e La Tuda (Diana and Tuda)

- Il Piacere dell'Onestà (The Pleasure Of Honesty)

- L'Imbecille (The Imbecile)

- L'Uomo, La Bestia e La Virtù (The Man, The Beast and The Virtue)

- Vestire gli Ignudi (Clothing The Naked)

- Così è (Se Vi Pare) (So It Is (If You Think So))

Poetry

Luigi Pirandello was also a poet. He published a total of five poetry books.

- Mal Giocondo (Playful Evil)

- Pasqua di Gea (Easter of Gea)

- Elegie Renane (Renanian Elegies)

- La Zampogna (The Bagpipe)

- Fiore di Chiave (Flower of Key)

Sources

- Baccolo, L. Pirandello. Milan:Bocca. 1949 (second edition).

- Di Pietro, L. Pirandello. Milano:Vita e Pensiero. 1950. (second edition)

- Ferrante, R. Luigi Pirandello. Firenze: Parenti. 1958.

- Gardair, Pirandello e il Suo Doppio. Rome: Abete. 1977.

- Janner, A. Luigi Pirandello. Firenze, La Nuova Italia. 1948.

- Monti, M. Pirandello, Palermo:Palumbo. 1974.

- Moravia. A. "Pirandello" in Fiera Leteraria.Rome. December 12, 1946.

- Pancrazi, P. "L'altro Pirandello" In Scrittori Italiani del Novecento. Bari:Laterza. 1939.

- Pasini. F. Pirandello nell'arte e nella vita. Padova. 1937.

- Virdia. F. Pirandello. Milan:Mursia. 1975.

- Fabrizio Tinaglia.Leonardo Da Vinci, Luigi Pirandello e i filosofi della storia. Ricerche inedite e storia della filosofia. Milano.Lampi di Stampa.2008.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Bergin, Thomas G (1976). "Pirandello, Luigi". In William D. Halsey. Collier's Encyclopedia. 19. New York: Macmillan Educational Corporation. pp. 76–78.

- ↑ Gaspare Giudice, Luigi Pirandello, UTET Torino 1963

- ↑ Gaspare Giudice, ibidem

- ↑ L'Ovra a Cinecittà di Natalia ed Emanuele V. Marino, Bollati Boringhieri, 2005

External links

- Works by Luigi Pirandello at Project Gutenberg

- The complete works of Pirandello in Italian and English section

- Presentation for Nobel Prize

- his bold and ingenious revival of dramatic and scenic art

- Listen to some Pirandello's work in Italian on audio MP3 - free download

- Pirandello's Girgenti. Places in Agrigento associated with his literary works

- Panoramic virtual tour of Piazza Luigi Pirandello in Agrigento

|

||||||||

[[cy:Luigi Pirandello]