Kilogram

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Unit system: | SI base unit |

| Unit of... | Mass |

| Symbol: | kg |

|

|

|

| 1 kg in... | is equal to... |

| Natural units | 4.59467(23)×107 Planck masses |

| Energy | 1.356392733(68)×1050 hertz [Note 1] |

| 89,875,517,873,681,764 joules (precisely) | |

| U.S. customary | ≈ 2.204622622 pounds-avoirdupois |

The kilogram (symbol: kg) is the base unit of mass in the International System of Units (SI, from the French Le Système International d’Unités),[Note 2] which is the modern standard governing the metric system. The kilogram is defined as being equal to the mass of the International Prototype Kilogram[1] (IPK),[Note 3] which is almost exactly equal to the mass of one liter of water. It is the only SI base unit with an SI prefix as part of its name. It is also the only SI unit that is still defined by an artifact rather than a fundamental physical property that can be reproduced in different laboratories.

In everyday usage, the mass of an object, which is measured in kilograms, is often referred to as its weight. However, the term weight in strict scientific contexts refers to the gravitational force of an object. Throughout most of the world, force is measured with the SI unit newton and the non-SI unit kilogram-force. Similarly, the avoirdupois (or international) pound, used in both the Imperial system and U.S. customary units, is a unit of mass and its related unit of force is the pound-force. The avoirdupois pound is defined as exactly 0.45359237 kg,[2] making one kilogram approximately equal to 2.2046 avoirdupois pounds.

Many units in the SI system are defined relative to the kilogram so its stability is important. After the International Prototype Kilogram had been found to vary in mass over time, the International Committee for Weights and Measures (known also by its French-language initials CIPM) recommended in 2005 that the kilogram be redefined in terms of a fundamental constant of nature.[3] No final decision is expected before 2011.[4]

Contents |

Nature of mass

The kilogram is a unit of mass, the measurement of which corresponds to the general, everyday notion of how “heavy” something is. However, mass is actually an inertial property; that is, the tendency of an object to remain at constant velocity unless acted upon by an outside force. According to Sir Isaac Newton's 324-year-old laws of motion and an important formula that sprang from his work, F = ma, an object with a mass, m, of one kilogram will accelerate, a, at one meter per second per second (about one-tenth the acceleration due to earth’s gravity)[Note 4] when acted upon by a force, F, of one newton.

While the weight of matter is entirely dependent upon the strength of gravity, the mass of matter is invariant.[Note 5] Accordingly, for astronauts in microgravity, no effort is required to hold objects off the cabin floor; they are “weightless”. However, since objects in microgravity still retain their mass and inertia, an astronaut must exert ten times as much force to accelerate a 10‑kilogram object at the same rate as a 1‑kilogram object.

On earth, a common swing set can demonstrate the relationship of force, mass, and acceleration without being appreciably influenced by weight (downward force). If one were to stand behind a large adult sitting stationary in a swing and give him a strong push, the adult would accelerate relatively slowly and swing only a limited distance forwards before beginning to swing backwards. Exerting that same effort while pushing on a small child would produce much greater acceleration.

History

Early definitions

On 7 April 1795, the gram was decreed in France to be equal to “the absolute weight of a volume of water equal to the cube of the hundredth part of the meter, at the temperature of melting ice.”[5] The concept of using a specified volume of water to define a unit measure of mass was first advanced by the English philosopher John Wilkins in 1668.[6][7]

Since trade and commerce typically involve items significantly more massive than one gram, and since a mass standard made of water would be inconvenient and unstable, the regulation of commerce necessitated the manufacture of a practical realization of the water-based definition of mass. Accordingly, a provisional mass standard was made as a single-piece, metallic artifact one thousand times more massive than the gram—the kilogram.

At the same time, work was commissioned to precisely determine the mass of a cubic decimeter (one liter) of water.[Note 6][5] Although the decreed definition of the kilogram specified water at 0 °C—its highly stable temperature point—the French chemist, Louis Lefèvre-Gineau and the Italian naturalist, Giovanni Fabbroni after several years of research chose to redefine the standard in 1799 to water’s most stable density point: the temperature at which water reaches maximum density, which was measured at the time as 4 °C.[Note 7][8] They concluded that one cubic decimeter of water at its maximum density was equal to 99.9265% of the target mass of the provisional kilogram standard made four years earlier.[Note 8][9] That same year, 1799, an all-platinum kilogram prototype was fabricated with the objective that it would equal, as close as was scientifically feasible for the day, the mass of one cubic decimeter of water at 4 °C. The prototype was presented to the Archives of the Republic in June and on 10 December 1799, the prototype was formally ratified as the Kilogramme des Archives (Kilogram of the Archives) and the kilogram was defined as being equal to its mass. This standard stood for the next ninety years.

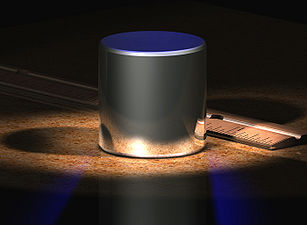

International Prototype Kilogram

Since 1889, the SI system defines the magnitude of the kilogram to be equal to the mass of the International Prototype Kilogram,[1] often referred to in the professional metrology world as the “IPK”. The IPK is made of a platinum alloy known as “Pt‑10Ir”, which is 90% platinum and 10% iridium (by mass) and is machined into a right-circular cylinder (height = diameter) of 39.17 millimeters to minimize its surface area.[10] The addition of 10% iridium improved upon the all-platinum Kilogram of the Archives by greatly increasing hardness while still retaining platinum’s many virtues: extreme resistance to oxidation, extremely high density, satisfactory electrical and thermal conductivities, and low magnetic susceptibility. The IPK and its six sister copies are stored at the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (known by its French-language initials BIPM) in an environmentally monitored safe in the lower vault located in the basement of the BIPM’s House of Breteuil in Sèvres on the outskirts of Paris (see External images, below for photographs). Three independently controlled keys are required to open the vault. Official copies of the IPK were made available to other nations to serve as their national standards. These are compared to the IPK roughly every 50 years.

The IPK is one of three cylinders made in 1879. In 1883, it was found to be indistinguishable from the mass of the Kilogram of the Archives made eighty-four years prior, and was formally ratified as the kilogram by the 1st CGPM in 1889.[10]

Modern measurements of Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water, which is pure distilled water with an isotopic composition representative of the average of the world’s oceans, show it has a density of 0.999975 ±0.000001 kg/L at its point of maximum density (3.984 °C) under one standard atmosphere (760 torr) of pressure.[11] Thus, a cubic decimeter of water at its point of maximum density is 25 parts per million less massive than the IPK. This small difference, and the fact that the mass of the IPK was indistinguishable from the mass of the Kilogram of the Archives, speak volumes of the scientists’ skills over 212 years ago when making their measurements of water’s properties and in manufacturing the Kilogram of the Archives.

Stability of the International Prototype Kilogram

By definition, the error in the measured value of the IPK’s mass is exactly zero; the IPK is the kilogram. However, any changes in the IPK’s mass over time can be deduced by comparing its mass to that of its official copies stored throughout the world, a process called “periodic verification.” For instance, the U.S. owns four 90% platinum / 10% iridium (Pt‑10Ir) kilogram standards, two of which, K4 and K20, are from the original batch of 40 replicas delivered in 1884.[Note 10] The K20 prototype was designated as the primary national standard of mass for the U.S. Both of these, as well as those from other nations, are periodically returned to the BIPM for verification.[Note 11]

Note that none of the replicas has a mass precisely equal to that of the IPK; their masses are calibrated and documented as offset values. For instance, K20, the U.S.’s primary standard, originally had an official mass of 1 kg − 39 micrograms (µg) in 1889; that is to say, K20 was 39 µg less than the IPK. A verification performed in 1948 showed a mass of 1 kg − 19 µg. The latest verification performed in 1999 shows a mass precisely identical to its original 1889 value. Quite unlike transient variations such as this, the U.S.’s check standard, K4, has persistently declined in mass relative to the IPK—and for an identifiable reason. Check standards are used much more often than primary standards and are prone to scratches and other wear. K4 was originally delivered with an official mass of 1 kg − 75 µg in 1889, but as of 1989 was officially calibrated at 1 kg − 106 µg and ten years later was 1 kg − 116 µg. Over a period of 110 years, K4 lost 41 µg relative to the IPK.[13]

Beyond the simple wear that check standards can experience, the mass of even the carefully stored national prototypes can drift relative to the IPK for a variety of reasons, some known and some unknown. Since the IPK and its replicas are stored in air (albeit under two or more nested bell jars), they gain mass through adsorption of atmospheric contamination onto their surfaces. Accordingly, they are cleaned in a process the BIPM developed between 1939 and 1946 known as “the BIPM cleaning method” that comprises lightly rubbing with a chamois soaked in equal parts ether and ethanol, followed by steam cleaning with bi-distilled water, and allowing the prototypes to settle for 7–10 days before verification.[Note 12] Cleaning the prototypes removes between 5 and 60 µg of contamination depending largely on the time elapsed since the last cleaning. Further, a second cleaning can remove up to 10 µg more. After cleaning—even when they are stored under their bell jars—the IPK and its replicas immediately begin gaining mass again. The BIPM even developed a model of this gain and concluded that it averaged 1.11 µg per month for the first 3 months after cleaning and then decreased to an average of about 1 µg per year thereafter. Since check standards like K4 are not cleaned for routine calibrations of other mass standards—a precaution to minimize the potential for wear and handling damage—the BIPM’s model of time-dependent mass gain has been used as an “after cleaning” correction factor.

Because the first forty official copies are made of the same alloy as the IPK and are stored under similar conditions, periodic verifications using a large number of replicas—especially the national primary standards, which are rarely used—can convincingly demonstrate the stability of the IPK. What has become clear after the third periodic verification performed between 1988 and 1992 is that masses of the entire worldwide ensemble of prototypes have been slowly but inexorably diverging from each other. It is also clear that the mass of the IPK lost perhaps 50 µg over the last century, and possibly significantly more, in comparison to its official copies.[12][14] The reason for this drift has eluded physicists who have dedicated their careers to the SI unit of mass. No plausible mechanism has been proposed to explain either a steady decrease in the mass of the IPK, or an increase in that of its replicas dispersed throughout the world.[Note 13][15][16][17] This relative nature of the changes amongst the world’s kilogram prototypes is often misreported in the popular press, and even some notable scientific magazines, which often state that the IPK simply “lost 50 µg” and omit the very important caveat of “in comparison to its official copies.”[Note 14] Moreover, there are no technical means available to determine whether or not the entire worldwide ensemble of prototypes suffers from even greater long-term trends upwards or downwards because their mass “relative to an invariant of nature is unknown at a level below 1000 µg over a period of 100 or even 50 years.”[14] Given the lack of data identifying which of the world’s kilogram prototypes has been most stable in absolute terms, it is equally as valid to state that the first batch of replicas has, as a group, gained an average of about 25 µg over one hundred years in comparison to the IPK.[Note 15]

What is known specifically about the IPK is that it exhibits a short-term instability of about 30 µg over a period of about a month in its after-cleaned mass.[18] The precise reason for this short-term instability is not understood but is thought to entail surface effects: microscopic differences between the prototypes’ polished surfaces, possibly aggravated by hydrogen absorption due to catalysis of the volatile organic compounds that slowly deposit onto the prototypes as well as the hydrocarbon-based solvents used to clean them.[17][19]

Scientists are seeing far greater variability in the prototypes than previously believed. The increasing divergence in the masses of the world’s prototypes and the short-term instability in the IPK has prompted research into improved methods to obtain a smooth surface finish using diamond-turning on newly manufactured replicas and has intensified the search for a new definition of the kilogram. See Proposed future definitions, below.[20]

Importance of the kilogram

The stability of the IPK is crucial because the kilogram underpins much of the SI system of measurement as it is currently defined and structured. For instance, the newton is defined as the force necessary to accelerate one kilogram at one meter per second squared. If the mass of the IPK were to change slightly, so too must the newton by a proportional degree. In turn, the pascal, the SI unit of pressure, is defined in terms of the newton. This chain of dependency follows to many other SI units of measure. For instance, the joule, the SI unit of energy, is defined as that expended when a force of one newton acts through one meter. Next to be affected is the SI unit of power, the watt, which is one joule per second. The ampere too is defined relative to the newton, and ultimately, the kilogram. With the magnitude of the primary units of electricity thus determined by the kilogram, so too follow many others; namely, the coulomb, volt, tesla, and weber. Even units used in the measure of light would be affected; the candela—following the change in the watt—would in turn affect the lumen and lux.

Because the magnitude of many of the units comprising the SI system of measurement is ultimately defined by the mass of a 132-year-old, golf ball-sized piece of metal, the quality of the IPK must be diligently protected to preserve the integrity of the SI system. Yet, in spite of the best stewardship, the average mass of the worldwide ensemble of prototypes and the mass of the IPK have likely diverged another 5.1 µg since the third periodic verification 22 years ago.[Note 16] Further, the world’s national metrology laboratories must wait for the fourth periodic verification to confirm whether the historical trends persisted.

Fortunately, definitions of the SI units are quite different from their practical realizations. For instance, the meter is defined as the distance light travels in a vacuum during a time interval of 1⁄299,792,458 of a second. However, the meter’s practical realization typically takes the form of a helium-neon laser, and the meter’s length is delineated—not defined—as 1,579,800.298728 wavelengths of light from this laser. Now suppose that the official measurement of the second was found to have drifted by a few parts per billion (it is actually exquisitely stable). There would be no automatic effect on the meter because the second—and thus the meter’s length—is abstracted via the laser comprising the meter’s practical realization. Scientists performing meter calibrations would simply continue to measure out the same number of laser wavelengths until an agreement was reached to do otherwise. The same is true with regard to the real-world dependency on the kilogram: if the mass of the IPK was found to have changed slightly, there would be no automatic effect upon the other units of measure because their practical realizations provide an insulating layer of abstraction. Any discrepancy would eventually have to be reconciled though because the virtue of the SI system is its precise mathematical and logical harmony amongst its units. If the IPK’s value were definitively proven to have changed, one solution would be to simply redefine the kilogram as being equal to the mass of the IPK plus an offset value, similarly to what is currently done with its replicas; e.g., “the kilogram is equal to the mass of the IPK + 42 parts per billion” (equivalent to 42 µg).

The long-term solution to this problem, however, is to liberate the SI system’s dependency on the IPK by developing a practical realization of the kilogram that can be reproduced in different laboratories by following a written specification. The units of measure in such a practical realization would have their magnitudes precisely defined and expressed in terms of fundamental physical constants. While major portions of the SI system would still be based on the kilogram, the kilogram would in turn be based on invariant, universal constants of nature. While this is a worthwhile objective and much work towards that end is ongoing, no alternative has yet achieved the uncertainty of a couple parts in 108 (~20 µg) required to improve upon the IPK. However, as of April 2007[update], the U.S.’s National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) had an implementation of the watt balance that was approaching this goal, with a demonstrated uncertainty of 36 µg.[21] See Watt balance, below.

Proposed future definitions

- In the following section, wherever numeric equalities are shown in ‘concise form’—such as 1.85487(14)×1043—the two digits between the parentheses denote the uncertainty at 1σ standard deviation (68% confidence level) in the two least significant digits of the significand.

The kilogram is the only SI unit that is still defined by an artifact. Note that the meter was also once defined as an artifact (a single platinum-iridium bar with two marks on it). However, it was eventually redefined in terms of invariant, fundamental constants of nature (the wavelength of light emitted by krypton, and later the speed of light) so that the standard can be reproduced in different laboratories by following a written specification. Today, physicists are investigating various approaches to doing the same with the kilogram. Some of the approaches are fundamentally very different from each other. Some are based on equipment and procedures that enable the reproducible production of new, kilogram-mass prototypes on demand (albeit with extraordinary effort) using measurement techniques and material properties that are ultimately based on, or traceable to, fundamental constants. Others are devices that measure either the acceleration or weight of hand-tuned, kilogram test masses and which express their magnitudes in electrical terms via special components that permit traceability to fundamental constants. Measuring the weight of test masses requires the precise measurement of the strength of gravity in laboratories. All approaches would precisely fix one or more constants of nature at a defined value. These different approaches are as follows:

Atom-counting approaches

Carbon-12

Though not offering a practical realization, this definition would precisely define the magnitude of the kilogram in terms of a certain number of carbon‑12 atoms. Carbon‑12 (12C) is an isotope of carbon. The mole is currently defined as “the quantity of entities (elementary particles like atoms or molecules) equal to the number of atoms in 12 grams of carbon‑12.” Thus, the current definition of the mole requires that 1000⁄12 (83⅓) moles of 12C has a mass of precisely one kilogram. The number of atoms in a mole, a quantity known as the Avogadro constant, is experimentally determined, and the current best estimate of its value is 6.02214179(30)×1023 entities per mole (CODATA, 2006). This new definition of the kilogram proposes to fix the Avogadro constant at precisely 6.02214179×1023 with the kilogram being defined as “the mass equal to that of 1000⁄12 · 6.02214179×1023 atoms of 12C.”

The accuracy of the measured value of the Avogadro constant is currently limited by the uncertainty in the value of the Planck constant—a measure relating the energy of photons to their frequency. That relative standard uncertainty has been 50 parts per billion (ppb) since 2006. By fixing the Avogadro constant, the practical effect of this proposal would be that the uncertainty in the mass of a 12C atom—and the magnitude of the kilogram—could be no better than the current 50 ppb uncertainty in the Planck constant. Under this proposal, the magnitude of the kilogram would be subject to future refinement as improved measurements of the value of the Planck constant become available; electronic realizations of the kilogram would be recalibrated as required. Conversely, an electronic definition of the kilogram (see Electronic approaches, below), which would precisely fix the Planck constant, would continue to allow 83⅓ moles of 12C to have a mass of precisely one kilogram but the number of atoms comprising a mole (the Avogadro constant) would continue to be subject to future refinement.

A variation on a 12C-based definition proposes to define the Avogadro constant as being precisely 84,446,8863 (≈6.02214098×1023) atoms. An imaginary realization of a 12-gram mass prototype would be a cube of 12C atoms measuring precisely 84,446,886 atoms across on a side. With this proposal, the kilogram would be defined as “the mass equal to 84,446,8863 × 83⅓ atoms of 12C.” The value 84,446,886 was chosen because it has a special property; its cube (the proposed new value for the Avogadro constant) is evenly divisible by twelve. Thus with this definition of the kilogram, there would be an integer number of atoms in one gram of 12C: 50,184,508,190,229,061,679,538 atoms.[22][Note 17]

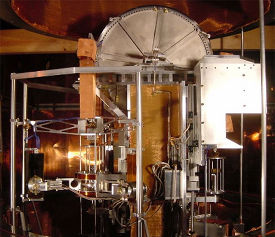

Avogadro project

Another Avogadro constant-based approach, known as the Avogadro project, would define and delineate the kilogram as a softball-size (93.6 mm diameter) sphere of silicon atoms. Silicon was chosen because a commercial infrastructure with mature processes for creating defect-free, ultra-pure monocrystalline silicon already exists to service the semiconductor industry. To make a practical realization of the kilogram, a silicon boule (a rod-like, single-crystal ingot) would be produced. Its isotopic composition would be measured with a mass spectrometer to determine its average relative atomic mass. The boule would be cut, ground, and polished into spheres. The size of a select sphere would be measured using optical interferometry to an uncertainty of about 0.3 nm on the radius—roughly a single atomic layer. The precise lattice spacing between the atoms in its crystal structure (≈192 pm) would be measured using a scanning X-ray interferometer. This permits its atomic spacing to be determined with an uncertainty of only three parts per billion. With the size of the sphere, its average atomic mass, and its atomic spacing known, the required sphere diameter can be calculated with sufficient precision and uncertainty to enable it to be finish-polished to a target mass of one kilogram.

Experiments are being performed on the Avogadro Project’s silicon spheres to determine whether their masses are most stable when stored in a vacuum, a partial vacuum, or ambient pressure. However, no technical means currently exist to prove a long-term stability any better than that of the IPK’s because the most sensitive and accurate measurements of mass are made with dual-pan balances like the BIPM’s FB‑2 flexure-strip balance (see External links, below). Balances can only compare the mass of a silicon sphere to that of a reference mass. Given the latest understanding of the lack of long-term mass stability with the IPK and its replicas, there is no known, perfectly stable mass artifact to compare against. Single-pan scales, which measure weight relative to an invariant of nature, are not precise to the necessary long-term uncertainty of 10–20 parts per billion. Another issue to be overcome is that silicon oxidizes and forms a thin layer (equivalent to 5–20 silicon atoms) of silicon dioxide (quartz) and silicon monoxide. This layer slightly increases the mass of the sphere, an effect which must be accounted for when polishing the sphere to its finish dimension. Oxidation is not an issue with platinum and iridium, both of which are noble metals that are roughly as cathodic as oxygen and therefore don’t oxidize unless coaxed to do so in the laboratory. The presence of the thin oxide layer on a silicon-sphere mass prototype places additional restrictions on the procedures that might be suitable to clean it to avoid changing the layer’s thickness or oxide stoichiometry.

All silicon-based approaches would fix the Avogadro constant but vary in the details of the definition of the kilogram. One approach would use silicon with all three of its natural isotopes present. About 7.78% of silicon comprises the two heavier isotopes: 29Si and 30Si. As described in Carbon‑12 above, this method would define the magnitude of the kilogram in terms of a certain number of 12C atoms by fixing the Avogadro constant; the silicon sphere would be the practical realization. This approach could accurately delineate the magnitude of the kilogram because the masses of the three silicon nuclides relative to 12C are known with great precision (relative uncertainties of 1 ppb or better). An alternative method for creating a silicon sphere-based kilogram proposes to use isotopic separation techniques to enrich the silicon until it is nearly pure 28Si, which has a relative atomic mass of 27.9769265325(19). With this approach, the Avogadro constant would not only be fixed, but so too would the atomic mass of 28Si. As such, the definition of the kilogram would be decoupled from 12C and the kilogram would instead be defined as 1000⁄27.9769265325 · 6.02214179×1023 atoms of 28Si (≈35.74374043 fixed moles of 28Si atoms). Physicists could elect to define the kilogram in terms of 28Si even when kilogram prototypes are made of natural silicon (all three isotopes present). Even with a kilogram definition based on theoretically pure 28Si, a silicon-sphere prototype made of only nearly pure 28Si would necessarily deviate slightly from the defined number of moles of silicon to compensate for various chemical and isotopic impurities as well as the effect of surface oxides.[23]

Ion accumulation

Another Avogadro-based approach, ion accumulation, since abandoned, would have defined and delineated the kilogram by precisely creating new metal prototypes on demand. It would have done so by accumulating gold or bismuth ions (atoms stripped of an electron) and counted them by measuring the electrical current required to neutralize the ions. Gold (197Au) and bismuth (209Bi) were chosen because they can be safely handled and have the two highest atomic masses among the mononuclidic elements that is effectively non-radioactive (bismuth) or is perfectly stable (gold). See also Table of nuclides.[Note 19]

With a gold-based definition of the kilogram for instance, the relative atomic mass of gold could have been fixed as precisely 196.9665687, from the current value of 196.9665687(6). As with a definition based upon carbon‑12, the Avogadro constant would also have been fixed. The kilogram would then have been defined as “the mass equal to that of precisely 1000⁄196.9665687 · 6.02214179×1023 atoms of gold” (precisely 3,057,443,620,887,933,963,384,315 atoms of gold or about 5.07700371 fixed moles).

In 2003, German experiments with gold at a current of only 10 µA demonstrated a relative uncertainty of 1.5%.[24] Follow-on experiments using bismuth ions and a current of 30 mA were expected to accumulate a mass of 30 g in six days and to have a relative uncertainty of better than 1 part in 106.[25] Ultimately, ion‑accumulation approaches proved to be unsuitable. Measurements required months and the data proved too erratic for the technique to be considered a viable future replacement to the IPK.[26]

Among the many technical challenges of the ion-deposition apparatus was obtaining a sufficiently high ion current (mass deposition rate) while simultaneously decelerating the ions so they could all deposit onto a target electrode embedded in a balance pan. Experiments with gold showed the ions had to be decelerated to very low energies to avoid sputtering effects—an phenomenon whereby ions that had already been counted ricochet off the target electrode or even dislodged atoms that had already been deposited. The deposited mass fraction in the 2003 German experiments only approached very close to 100% at ion energies of less than around 1 eV (<1 km/s for gold).[24]

If the kilogram had been defined as a precise quantity of gold or bismuth atoms deposited with an electric current, not only would the Avogadro constant and the atomic mass of gold or bismuth had to have been precisely fixed, but also the value of the elementary charge (e), likely to 1.602176487×10−19 C (from the present 2006 CODATA value of 1.602176487(40)×10−19). Doing so would have effectively defined the ampere as a flow of 1⁄1.602176487×10−19 (6,241,509,647,120,417,390) electrons per second past a fixed point in an electric circuit. The SI unit of mass would have been fully defined by having precisely fixed the values of the Avogadro constant and elementary charge, and by exploiting the fact that the atomic masses of bismuth and gold atoms are invariant, universal constants of nature.

Beyond the slow speed of making a new mass standard and the poor reproducibility, there were other intrinsic shortcomings to the ion‑accumulation approach that proved to be formidable obstacles to ion-accumulation-based techniques becoming a practical realization. The apparatus necessarily required that the deposition chamber have an integral balance system to enable the convenient calibration of a reasonable quantity of transfer standards relative to any single internal ion-deposited prototype. Furthermore, the mass prototypes produced by ion deposition techniques would have been nothing like the freestanding platinum-iridium prototypes currently in use; they would have been deposited onto—and become part of—an electrode imbedded into one pan of a special balance integrated into the device. Moreover, the ion-deposited mass wouldn’t have had a hard, highly polished surface that can be vigorously cleaned like those of current prototypes. Gold, while dense and a noble metal (resistant to oxidation and the formation of other compounds), is extremely soft so an internal gold prototype would have to be kept well isolated and scrupulously clean to avoid contamination and the potential of wear from having to remove the contamination. Bismuth, which is an inexpensive metal used in low-temperature solders, slowly oxidizes when exposed to room-temperature air and forms other chemical compounds and so would not have produced stable reference masses unless it was continually maintained in a vacuum or inert atmosphere.

Electronic approaches

Watt balance

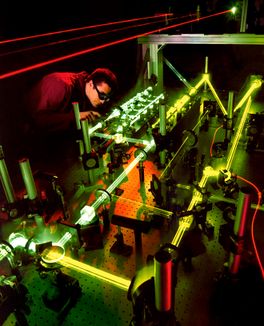

The watt balance is essentially a single-pan weighing scale that measures the electric power necessary to oppose the weight of a kilogram test mass as it is pulled by earth’s gravity. It is a variation of an ampere balance in that it employs an extra calibration step that nulls the effect of geometry. The electric potential in the watt balance is delineated by a Josephson voltage standard, which allows voltage to be linked to an invariant constant of nature with extremely high precision and stability. Its circuit resistance is calibrated against a quantum Hall resistance standard.

The watt balance requires exquisitely precise measurement of gravity in a laboratory (see “FG‑5 absolute gravimeter” in External images, below). For instance, the NIST compensates for earth’s gravity gradient of 3.09 µGal per centimeter when the elevation of the center of the gravimeter differs from that of the nearby test mass in the watt balance; a change in the weight of a one-kilogram test mass that equates to about 3.16 µg/cm.

In April 2007, the NIST’s implementation of the watt balance demonstrated a combined relative standard uncertainty (CRSU) of 36 µg and a short-term resolution of 10–15 µg.[21][Note 20] The UK’s National Physical Laboratory’s watt balance demonstrated a CRSU of 70.3 µg in 2007.[27] That watt balance was disassembled and shipped in 2009 to Canada’s Institute for National Measurement Standards (part of the National Research Council), where research and development with the device could continue.

With the watt balance, the kilogram would be redefined and internationally recognized in terms of two invariants of nature: the speed of light (c) and the Planck constant (h), which is a measure that relates the energy of photons to their frequency. The Planck constant would be fixed; for example, to h = 6.62606896×10−34 J·s (from the 2006 CODATA value of 6.62606896(33)×10−34 J·s).[Note 21] The kilogram would relate to these two fundamental constants of nature via the formula 1 kg = c2/h = f, which is to say, the mass of the kilogram would be equivalent to the square of the speed of light divided by the Planck constant, where the defined amount of energy is expressed as a simple frequency. The kilogram would thus be defined as “the mass of a body at rest whose equivalent energy equals the energy of photons whose frequencies sum to ( 299,792,4582⁄6.62606896×10−34 ) hertz.” [28][Note 22] This quotient is approximately 1.356392733×1050 hertz (symbol = Hz), which is expressed here at a precision of better than one part per billion—better precision than the watt balance will be able to operate at for the foreseeable future.

A “sum of photon frequencies” means the photon energy that is equivalent to one kilogram could be expressed in terms of a single photon oscillating at about 1.356×1050 Hz, two photons that each have half that frequency (about 6.78×1049 Hz), 100 photons with one‑hundredth the specified value (about 1.356×1048 Hz), or approximately 5.95×1035 photons from a chemical oxygen-iodine laser, which oscillate at about 2.279×1014 Hz. This sum of frequencies is an extraordinarily high value; a single photon oscillating at 1.356×1050 Hz would be oscillating over a trillion-trillion times faster than the highest-energy gamma ray photons ever observed.

By fixing the value of the Planck constant and defining the kilogram in terms of its equivalent energy, the magnitude of the kilogram is being measured in terms of Albert Einstein’s famous equation E = mc2, which holds that mass can be expressed in terms of energy and vice versa. Due to the way the SI system of measurement is logically structured, E = mc2 means one kilogram is precisely equivalent to an energy of 89,875,517,873,681,764 joules, which is the square of the speed of light in meters per second (299,792,4582), or as stated above, this energy in joules can be divided by the Planck constant to express the energy as a sum of photon frequencies. Regardless of the units of measure employed, one kilogram has an exceedingly great deal of equivalent energy; it is comparable to that released in the explosion of a fairly powerful hydrogen bomb: a yield of approximately 21 megatons. At a slower rate, the largest electric power-producing facility in the United States, Grand Coulee Dam, would typically require over 14 months to generate nearly 90 quadrillion joules of energy. In terms of a collection of photons that have a total energy equivalent to one kilogram, the approximately 5.95×1035 near‑infrared photons from the above-mentioned chemical oxygen-iodine laser, which is a weapon system intended for destroying intercontinental ballistic missiles, would require a beam length that could reach beyond any of the 200 stars nearest the sun; with a beam intensity of one megawatt per square centimeter and a diameter of 3.6 centimeters, it would have a length of 280 light‑years.

Fortunately, the kilogram’s mass/energy equivalence is established indirectly in the watt balance; gravity serves as a crucial translation tool that is exploited to measure the “mass vs. energy” relationship via a “force vs. electrical power” relationship. Since gravity is the weakest of nature’s fundamental forces and since earth’s gravity is relatively modest compared to other celestial bodies, only a relatively small amount of electrical power is required to counter the weight of one kilogram on earth. However, the force of gravity varies significantly—nearly one percent—depending upon where on earth’s surface the measurement is made (see Earth’s gravity ). Even more problematic, there are subtle seasonal variations in gravity due to changes in underground water tables, and even semimonthly and diurnal changes due to tidal distortions in the earth’s shape caused by the moon. Although gravity would not be a term in the definition of the kilogram, gravity would be a crucial term used in the delineation of the kilogram when relating energy to power. Accordingly, the ‘gravity’ term must be measured with at least as much precision and accuracy as are the other terms. It is therefore highly desirable that gravity measurements also be traceable to fundamental constants of nature. For the most precise work in mass metrology, gravitational acceleration is measured using dropping-mass absolute gravimeters that contain an iodine-stabilized helium–neon laser interferometer. The fringe-signal, frequency-sweep output from the interferometer is measured with a rubidium atomic clock. Since this type of dropping-mass gravimeter derives its accuracy and stability from the constancy of the speed of light as well as the innate properties of helium, neon, and rubidium atoms, the ‘gravity’ term in the delineation of an all-electronic kilogram is also measured in terms of invariants of nature—and with very high precision. For instance, in the basement of the NIST’s Gaithersburg facility in 2009, when measuring the gravity acting upon Pt‑10Ir test masses (which are denser, smaller, and have a slightly lower center of gravity inside the watt balance than stainless steel masses), the measured value was typically within 8 ppb of 9.80101644 m/s2.[29]

The virtue of electronic realizations like the watt balance is that the definition and dissemination of the kilogram would no longer be dependent upon the stability of kilogram prototypes, which must be very carefully handled and stored. It would free physicists from the need to rely on assumptions about the stability of those prototypes, including those that would be manufactured under atom-counting schemes. Instead, hand-tuned, close-approximation mass standards would simply be weighed and documented as being equal to one kilogram plus an offset value. With the watt balance, the kilogram would not only be delineated in electrical and gravity terms, all of which are traceable to invariants of nature; it would be defined in electrical terms in a manner that is directly traceable to just two fundamental constants of nature. Mass artifacts—physical objects calibrated in a watt balance, including the IPK—would become transfer standards.

Scales like the watt balance also permit more flexibility in choosing materials with especially desirable properties for mass standards. For instance, Pt‑10Ir could continue to be used so that the specific gravity of newly produced mass standards would be the same as existing national primary and check standards (≈21.55 g/ml). This would reduce the relative uncertainty when making mass comparisons in air. Alternately, entirely different materials and constructions could be explored with the objective of producing mass standards with greater stability. For instance, osmium-iridium alloys could be investigated if platinum’s propensity to absorb hydrogen (due to catalysis of VOCs and hydrocarbon-based cleaning solvents) and atmospheric mercury proved to be sources of instability. Also, vapor-deposited, protective ceramic coatings like nitrides could be investigated for their suitability to isolate these new alloys.

The challenge with watt balances is not only in reducing their uncertainty, but also in making them truly practical realizations of the kilogram. Nearly every aspect of watt balances and their support equipment requires such extraordinarily precise and accurate, state-of-the-art technology that—unlike a device like an atomic clock—few countries would currently choose to fund their operation. For instance, the NIST’s watt balance used four resistance standards in 2007, each of which was rotated through the watt balance every two to six weeks after being calibrated in a different part of NIST headquarters facility in Gaithersburg, Maryland. It was found that simply moving the resistance standards down the hall to the watt balance after calibration altered their values 10 ppb (equivalent to 10 µg) or more.[30] Present-day technology is insufficient to permit stable operation of watt balances between even biannual calibrations. If the kilogram is defined in terms of the Planck constant, it is likely there will only be a few—at most—watt balances initially operating in the world.

Ampere-based force

This approach would define the kilogram as “the mass which would be accelerated at precisely 2×10−7 m/s2 when subjected to the per-meter force between two straight parallel conductors of infinite length, of negligible circular cross section, placed one meter apart in vacuum, through which flow a constant current of 1⁄1.602176487×10−19 (≈6,241,509,647,120,417,390) elementary charges per second.”

Effectively, this would define the kilogram as a derivative of the ampere rather than present relationship, which defines the ampere as a derivative of the kilogram. This redefinition of the kilogram would specify elementary charge (e) as precisely 1.602176487×10−19 coulomb rather than the current 2006 CODATA value of 1.602176487(40)×10−19. Effectively, the coulomb would be the sum of 6,241,509,647,120,417,390 elementary charges. It would necessarily follow that the ampere (one coulomb per second) would also become an electrical current of this precise quantity of elementary charges per second passing a given point in an electric circuit.

The virtue of a practical realization based upon this definition is that unlike the watt balance and other scale-based methods, all of which require the careful characterization of gravity in the laboratory, this method delineates the magnitude of the kilogram directly in the very terms that define the nature of mass: acceleration due to an applied force. Unfortunately, it is extremely difficult to develop a practical realization based upon accelerating masses. Experiments over a period of years in Japan with a superconducting, 30 g mass supported by diamagnetic levitation never achieved an uncertainty better than ten parts per million. Magnetic hysteresis was one of the limiting issues. Other groups are continuing this line of research using different techniques to levitate the mass.[31]

SI multiples

Because SI prefixes may not be concatenated (serially linked) within the name or symbol for a unit of measure, SI prefixes are used with the gram, not the kilogram, which already has a prefix as part of its name.[32] For instance, one-millionth of a kilogram is 1 mg (one milligram), not 1 µkg (one microkilogram).

| Submultiples | Multiples | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | Symbol | Name | Value | Symbol | Name | |

| 10−1 g | dg | decigram | 101 g | dag | decagram | |

| 10−2 g | cg | centigram | 102 g | hg | hectogram | |

| 10−3 g | mg | milligram | 103 g | kg | kilogram | |

| 10−6 g | µg | microgram (mcg) | 106 g | Mg | megagram (tonne) | |

| 10−9 g | ng | nanogram | 109 g | Gg | gigagram | |

| 10−12 g | pg | picogram | 1012 g | Tg | teragram | |

| 10−15 g | fg | femtogram | 1015 g | Pg | petagram | |

| 10−18 g | ag | attogram | 1018 g | Eg | exagram | |

| 10−21 g | zg | zeptogram | 1021 g | Zg | zettagram | |

| 10−24 g | yg | yoctogram | 1024 g | Yg | yottagram | |

| Common prefixes are in bold face.[Note 23] | ||||||

- When the Greek lowercase “µ” (mu) in the symbol of microgram is typographically unavailable, it is occasionally—although not properly—replaced by Latin lowercase “u”.

- The microgram is often abbreviated “mcg”, particularly in pharmaceutical and nutritional supplement labeling, to avoid confusion since the “µ” prefix is not well recognized outside of technical disciplines.[Note 24] Note however, that the abbreviation “mcg”, is also the symbol for an obsolete CGS unit of measure known as the “millicentigram”, which is equal to 10 µg.

- The unit name “megagram” is rarely used, and even then, typically only in technical fields in contexts where especially rigorous consistency with the units of measure is desired. For most purposes, the unit “tonne” is instead used. The tonne and its symbol, t, were adopted by the CIPM in 1879. It is a non-SI unit accepted by the BIPM for use with the SI. According to the BIPM, “In English speaking countries this unit is usually called ‘metric ton’.”[33] Note also that the unit name “megatonne” or “megaton” (Mt) is often used in general-interest literature on greenhouse gas emissions whereas the equivalent value in scientific papers on the subject is often the “teragram” (Tg).

Glossary

- Abstracted: Isolated and its effect changed in form, often simplified or made more accessible in the process.

- Artifact: A simple human-made object used directly as a comparative standard in the measurement of a physical quantity.

- Check standard:

- A standard body’s backup replica of the International Prototype Kilogram (IPK).

- A secondary kilogram mass standard used as a stand-in for the primary standard during routine calibrations.

- Definition: A formal, specific, and exact specification.

- Delineation: The physical means used to mark a boundary or express the magnitude of an entity.

- Disseminate: To widely distribute the magnitude of a unit of measure, typically via replicas and transfer standards.

- IPK: Abbreviation of “International Prototype Kilogram” (CG image), the mass artifact in France internationally recognized as having the defining mass of precisely one kilogram.

- Magnitude: The extent or numeric value of a property

- National prototype: A replica of the IPK possessed by a nation.

- Practical realization: A readily reproducible apparatus to conveniently delineate the magnitude of a unit of measure.

- Primary national standard:

- A replica of the IPK possessed by a nation

- The least used replica of the IPK when a nation possesses more than one.

- Prototype:

- A human-made object that serves as the defining comparative standard in the measurement of a physical quantity.

- A human-made object that serves as the comparative standard in the measurement of a physical quantity.

- The IPK and any of its replicas

- Replica: An official copy of the IPK.

- Sister copy: One of six official copies of the IPK that are stored in the same safe as the IPK and are used as check standards by the BIPM.

- Transfer standard: An artifact or apparatus that reproduces the magnitude of a unit of measure in a different, usually more practical, form.

See also

|

|

Notes

- ↑ One kilogram at rest has an equivalent energy equal to the energy of photons whose frequencies sum to this value.

- ↑ The spelling kilogram is the modern spelling used by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM), the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the U.K.’s National Measurement Office, National Research Council Canada, and Australia’s National Measurement Institute. The traditional British-English spelling kilogramme is sometimes also used.

- ↑ Also known by its French-language name Le Grand K.

- ↑ In professional metrology (the science of measurement), the acceleration of earth’s gravity is taken as standard gravity (symbol: gn), which is defined as precisely 9.80665 meters per square second (m/s2). The expression “1 m/s2 ” means that for every second that elapses, velocity changes an additional 1 meter per second. In more familiar terms: an acceleration of 1 m/s2 can also be expressed as a rate of change in velocity of precisely 3.6 km/h per second (≈2.2 mph per second).

- ↑ Matter has invariant mass assuming it is not traveling at a relativistic speed with respect to an observer. According to Einstein’s theory of special relativity, the relativistic mass (apparent mass with respect to an observer) of an object or particle with rest mass m0 increases with its speed as M = γm0 (where γ is the Lorentz factor). This effect is vanishingly small at everyday speeds, which are many orders of magnitude less than the speed of light. For example, to change the mass of a kilogram by 1 μg (1 ppb, about the level of detection by current technology) would require moving it at 0.0045% of the speed of light relative to an observer, which is 13.4 km/s (30,000 mph).

As regards the kilogram, relativity’s effect upon the constancy of matter’s mass is simply an interesting scientific phenomenon that has zero effect on the definition of the kilogram and its practical realizations.

- ↑ The same decree also defined the liter as follows: “Liter: the measure of volume, both for liquid and solids, for which the displacement would be that of a cube [with sides measuring] one-tenth of a meter.” Original text: “Litre, la mesure de capacité, tant pour les liquides que pour les matières sèches, dont la contenance sera celle du cube de la dixièrne partie du mètre.”

- ↑ Modern measurements show the temperature at which water reaches maximum density is 3.984 °C. However, the scientists at the close of the 18th century concluded that the temperature was 4 °C.

- ↑ The provisional kilogram standard had been fabricated in accordance with a single, inaccurate measurement of the density of water made earlier by Antoine Lavoisier and René Just Haüy, which showed that one cubic decimeter of distilled water at 0 °C had a mass of 18,841 grains in France’s soon-to-be-obsoleted poids de marc system. The newer, highly accurate measurements by Lefèvre‑Gineau and Fabbroni concluded that the mass of a cubic decimeter of water at the new temperature of 4 °C—a condition at which water is denser—was actually less massive, at 18,827.15 grains, than the earlier inaccurate value assumed for 0 °C water.

France’s metric system had been championed by Charles Maurice de Talleyrand‑Périgord. On 30 March 1791, four days after Talleyrand forwarded a specific proposal on how to proceed with the project, the French government ordered a committee known as the Academy to commence work on accurately determining the magnitude of the base units of the new metric system. The Academy divided the task among five commissions. The commission charged with determining the mass of a cubic decimeter of water originally comprised Lavoisier and Haüy but their work was finished by Louis Lefèvre‑Gineau and Giovanni Fabbroni.

Neither Lavoisier nor Haüy can be blamed for participating in an initial—and inaccurate—measurement and for leaving the final work to Lefèvre‑Gineau and Fabbroni to finish in 1799. As a member of the Ferme générale, Lavoisier was also one of France’s 28 tax collectors. He was consequently convicted of treason during the waning days of the Reign of Terror period of the French Revolution and beheaded on 8 May 1794. Lavoisier’s partner, Haüy, was also thrown into prison and was himself at risk of going to the guillotine but his life was spared after a renowned French naturalist interceded.

- ↑ Prototype No. 8(41) was accidentally stamped with the number 41, but its accessories carry the proper number 8. Since there is no prototype marked 8, this prototype is referred to as 8(41).

- ↑ The other two Pt‑10Ir standards owned by the U.S. are K79, from a new series of prototypes (K64–K80) that were diamond-turned directly to a finish mass, and K85, which is used for watt balance experiments (see Watt balance, above).

- ↑ Extraordinary care is exercised when transporting prototypes. In 1984, the K4 and K20 prototypes were hand-carried in the passenger section of separate commercial airliners.

- ↑ Before the BIPM’s published report in 1994 detailing the relative change in mass of the prototypes, different standard bodies used different techniques to clean their prototypes. The NIST’s practice before then was to soak and rinse its two prototypes first in benzene, then in ethanol, and to then clean them with a jet of bi-distilled water steam.

- ↑ Note that if the ∆ 50 µg between the IPK and its replicas was entirely due to wear, the IPK would have to have lost 150 million billion more platinum and iridium atoms over the last century than its replicas. That there would be this much wear, much less a difference of this magnitude, is thought unlikely; 50 µg is roughly the mass of a fingerprint. Specialists at the BIPM in 1946 carefully conducted cleaning experiments and concluded that even vigorous rubbing with a chamois—if done carefully—did not alter the prototypes’ mass. More recent cleaning experiments at the BIPM, which were conducted on one particular prototype (K63), and which benefited from the then-new NBS‑2 balance, demonstrated 2 µg stability.

Many theories have been advanced to explain the divergence in the masses of the prototypes. One theory posits that the relative change in mass between the IPK and its replicas is not one of loss at all and is instead a simple matter that the IPK has gained less than the replicas. This theory begins with the observation that the IPK is uniquely stored under three nested bell jars whereas its six sister copies stored alongside it in the vault as well as the other replicas dispersed throughout the world are stored under only two. This theory is also founded on two other facts: that platinum has a strong affinity for mercury, and that atmospheric mercury is significantly more abundant in the atmosphere today than at the time the IPK and its replicas were manufactured. The burning of coal is a major contributor to atmospheric mercury and both Denmark and Germany have high coal shares in electrical generation. Conversely, electrical generation in France, where the IPK is stored, is mostly nuclear. This theory is supported by the fact that the mass divergence rate—relative to the IPK—of Denmark’s prototype, K48, since it took possession in 1949 is an especially high 78 µg per century while that of Germany’s prototype has been even greater at 126 µg/century ever since it took possession of K55 in 1954. However, still other data for other replicas isn’t supportive of this theory. This mercury absorption theory is just one of many advanced by the specialists to account for the relative change in mass. To date, each theory has either proven implausible, or there are insufficient data or technical means to either prove or disprove it.

- ↑ Even well respected organizations incorrectly represent the relative nature of the mass divergence as being one of mass loss, as exemplified by this site at Science Daily, and this site at PhysOrg.com, and this site at Sandia National Laboratories. The root of the problem is often the reporters’ failure to correctly interpret or paraphrase nuanced scientific concepts, as exemplified by this 12 September 2007 story by the Associated Press published on PhysOrg.com. In that AP story, Richard Davis—who used to be the NIST’s kilogram specialist and now works for the BIPM in France—was correctly quoted by the AP when he stated that the mass change is a relative issue. Then the AP summarized the nature of issue with this lead-in to the story: “A kilogram just isn't what it used to be. The 118-year-old cylinder that is the international prototype for the metric mass, kept tightly under lock and key outside Paris, is mysteriously losing weight — if ever so slightly.” Like many of the above-linked sites, the AP also misreported the age of the IPK, using the date of its adoption as the mass prototype, not the date of the cylinder’s manufacture. This is a mistake even Scientific American fell victim to in a print edition.

- ↑ The mean change in mass of the first batch of replicas relative to the IPK over one hundred years is +23.5 µg with a standard deviation of 30 µg. Per The Third Periodic Verification of National Prototypes of the Kilogram (1988–1992), G. Girard, Metrologia 31 (1994) Pg. 323, Table 3. Data is for prototypes K1, K5, K6, K7, K8(41), K12, K16, K18, K20, K21, K24, K32, K34, K35, K36, K37, K38, and K40; and excludes K2, K23, and K39, which are treated as outliers. This is a larger data set than is shown in the chart at the top of this section, which corresponds to Figure 7 of G. Girard’s paper.

- ↑ Assuming the past trend continues, whereby the mean change in mass of the first batch of replicas relative to the IPK over one hundred years was +23.5 σ30 µg.

- ↑ The uncertainty in the Avogadro constant narrowed since this proposal was first submitted to American Scientist for publication. The 2006 CODATA value for the Avogadro constant has a relative standard uncertainty of 50 parts per billion and the only cube root values within this uncertainty must fall within the range of 84,446,889.8 ±1.4; that is, there are only three integer cube roots (…89, …90, and …91) in this range and the value 84,446,886 falls outside of it. Unfortunately, none of the three integer values within the range possess the property of their cubes being divisible by twelve; one gram of 12C could not comprise an integer number of atoms. If the value 84,446,886 was adopted to define the kilogram, many other constants of nature and electrical units would have to be revised an average of about 0.13 part per million. The straightforward adjustment to this approach advanced by the group would instead define the kilogram as “the mass equal to 84,446,8903 × 83⅓ atoms of carbon‑12.” This proposed value for the Avogadro constant (≈6.02214184×1023) falls neatly within the 2006 CODATA value of 6.02214179(30)×1023 and the proposed definition of the kilogram produces an integer number of atoms in 12 grams of carbon‑12 (602,214,183,858,071,454,769,000 atoms), but not for 1 gram or 1 kilogram.

- ↑ The sphere shown in the photograph has an out-of-roundness value (peak to valley on the radius) of 50 nm. According to ACPO, they improved on that with an out-of-roundness of 35 nm. On the 93.6 mm diameter sphere, an out-of-roundness of 35 nm (undulations of ±17.5 nm) is a fractional roundness (∆r /r ) = 3.7×10−7. Scaled to the size of earth, this is equivalent to a maximum deviation from sea level of only 2.4 m. The roundness of that ACPO sphere is exceeded only by two of the four fused-quartz gyroscope rotors flown on Gravity Probe B, which were manufactured in the late 1990s and given their final figure at the W.W. Hansen Experimental Physics Lab at Stanford University. Particularly, “Gyro 4” is recorded in the Guinness database of world records (their database, not in their book) as the world’s roundest man-made object. According to a published report (221 kB PDF, here) and the GP‑B public affairs coordinator at Stanford University, of the four gyroscopes onboard the probe, Gyro 4 has a maximum surface undulation from a perfect sphere of 3.4 ±0.4 nm on the 38.1 mm diameter sphere, which is a ∆r /r = 1.8×10−7. Scaled to the size of earth, this is equivalent to an undulation the size of North America rising slowly up out of the sea (in molecular-layer terraces 11.9 cm high), reaching a maximum elevation of 1.14 ±0.13 m in Nebraska, and then gradually sloping back down to sea level on the other side of the continent.

- ↑ In 2003, the same year the first gold-deposition experiments were conducted, physicists found that the only naturally occurring isotope of bismuth, 209Bi, is actually very slightly radioactive, with the longest known radioactive half-life of any naturally occurring element that decays via alpha radiation—a half-life of 19±2×1018 years. As this is 1.4 billion times the age of the universe, 209Bi is considered a stable isotope for most practical applications (those unrelated to such disciplines as nucleocosmochronology and geochronology). In other terms, 99.999999983% of the bismuth that existed on earth 4.567 billion years ago still exists today. Only two mononuclidic elements are heavier than bismuth and only one approaches its stability: thorium. Long considered a possible replacement for uranium in nuclear reactors, thorium can cause cancer when inhaled because it is over 1.2 billion times more radioactive than bismuth. It also has such a strong tendency to oxidize that its powders are pyrophoric. These characteristics make thorium unsuitable in ion-deposition experiments. See also Isotopes of bismuth, Isotopes of gold and Isotopes of thorium.

- ↑ The combined relative standard uncertainty (CRSU) of these measurements, as with all other tolerances and uncertainties in this article unless otherwise noted, have a 1σ standard deviation, which equates to a confidence level of about 68%; that is to say, 68% of the measurements fall within the stated tolerance.

- ↑ The Planck constant’s unit of measure “joule-second” (J·s) may be more easily understood when expressed as a “joule per hertz” (J/Hz). Universally, an individual photon has an energy that is proportional to its frequency. This relationship is 6.62606896(33)×10−34 J/Hz and 1.50919045(8)×1033 Hz/J.

- ↑ The SI unit, hertz (the reciprocal second) cannot normally be used as a measure of energy. When referring to a watt balance-based definition of the kilogram, the disciplines of professional metrology and physics customarily refer to the quotient of E/h (energy divided by a factor relating the energy of photons to their frequency) as a frequency, f, and add a crucial caveat in prose explaining that the unit of measure, hertz, represents an energy equivalent to that of photons whose frequencies sum to the stated value. However, even authoritative sources will, when communicating to a general-interest audience, sometimes state that one kilogram is equivalent to 1.356392733(68)×1050 Hz and attach no explanation (other than displaying the formula c2/h) that the true measure is a corresponding energy, as exemplified here at the NIST’s Fundamental physical constants: “Energy Equivalents” calculator.

- ↑ Criterion: A combined total of at least 250,000 Google hits on both the modern spelling (‑gram) and the traditional British spelling (‑gramme).

- ↑ The practice of using the abbreviation “mcg” rather than the SI symbol “µg” was formally mandated for medical practitioners in 2004 by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) in their “Do Not Use” List: Abbreviations, Acronyms, and Symbols because hand-written expressions of “µg” can be confused with “mg”, resulting in a thousand-fold overdosing. The mandate was also adopted by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Resolution of the 1st CGPM (1889)". BIMP. http://www.bipm.org/en/CGPM/db/1/1/.

- ↑ "Appendix 8 – Customary System of Weights and Measures" (1.6 MB PDF). National Bureau of Standards (predecessor of the NIST). http://physics.nist.gov/Pubs/SP447/app8.pdf.

"Frequently Asked Questions". National Research Council Canada. http://inms-ienm.nrc-cnrc.gc.ca/faq_mech_e.html#Q1.

"Converting Measurements to Metric—NIST FAQs". NIST. http://www.nist.gov/public_affairs/faqs/qmetric.htm.

"Metric Conversions". U.K. National Weights & Measures Laboratory. http://www.nwml.gov.uk/faqs.aspx?ID=8.

"Fed-Std-376B, Preferred Metric Units for General Use By the Federal Government" (294 KB PDF). NIST. http://ts.nist.gov/WeightsAndMeasures/Metric/upload/fs376-b.pdf. - ↑ 94th Meeting of the International Committee for Weights and Measures (2005) Recommendation 1: Preparative steps towards new definitions of the kilogram, the ampere, the kelvin and the mole in terms of fundamental constants

- ↑ 23rd General Conference on Weights and Measures (2007). Resolution 12: On the possible redefinition of certain base units of the International System of Units (SI).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Decree on weights and measures". 7 April 1795. http://smdsi.quartier-rural.org/histoire/18germ_3.htm. "Gramme, le poids absolu d'un volume d'eau pure égal au cube de la centième partie du mètre , et à la température de la glace fondante."

- ↑ An Essay towards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language (Reproduction)

- ↑ An Essay towards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language (Transcription)

- ↑ "L'histoire du mètre, la détermination de l'unité de poids". http://histoire.du.metre.free.fr/fr/index.htm.

- ↑ Ronald Edward Zupko (1990). Revolution in Measurement: Western European Weights and Measures Since the Age of Science. DIANE Publishing.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 New Techniques in the Manufacture of Platinum-Iridium Mass Standards, T. J. Quinn, Platinum Metals Rev., 1986, 30, (2), pp. 74–79

- ↑ Isotopic composition and temperature per London South Bank University’s “List of physicochemical data concerning water”, density and uncertainty per NIST Standard Reference Database Number 69 (retrieved 5 April 2010)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 G. Girard (1994). "The Third Periodic Verification of National Prototypes of the Kilogram (1988–1992)". Metrologia 31 (4): 317–336. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/31/4/007.

- ↑ Z. J. Jabbour; S. L. Yaniv (Jan–Feb 2001). 3.5 "The Kilogram and Measurements of Mass and Force". J. Res. Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. 106 (1): 25–46. http://nvl.nist.gov/pub/nistpubs/jres/106/1/j61jab.pdf 3.5.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Mills, Ian M.; Mohr, Peter J; Quinn, Terry J; Taylor, Barry N; Williams, Edwin R (April 2005). "Redefinition of the kilogram: a decision whose time has come". Metrologia 42 (2): 71–80. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/42/2/001. http://membership.acs.org/N/NOME/appendix_i%20pt_1_082007.pdf. Retrieved 2009-11-25.

- ↑ Davis, Richard (December 2003). "The SI unit of mass". Metrologia 40 (6): 299–305. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/40/6/001. http://charm.physics.ucsb.edu/courses/ph21_05/kilogrampaper.pdf. Retrieved 2009-11-25.

- ↑ R. S. Davis (July–August 1985). "Recalibration of the U.S. National Prototype Kilogram". Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards 90 (4). http://nvl.nist.gov/pub/nistpubs/jres/090/4/V90-4.pdf.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Conjecture why the IPK drifts, R. Steiner, NIST, 11 Sept. 2007.

- ↑ Report to the CGPM, 14th meeting of the Consultative Committee for Units (CCU), April 2001, 2. (ii); General Conference on Weights and Measures, 22nd Meeting, October 2003, which stated “The kilogram is in need of a new definition because the mass of the prototype is known to vary by several parts in 108 over periods of time of the order of a month…” (3.2 MB ZIP file, here).

- ↑ BBC, Getting the measure of a kilogram.

- ↑ General section citations: Recalibration of the U.S. National Prototype Kilogram, R. S. Davis, Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards, 90, No. 4, July–August 1985 (5.5 MB PDF, here); and The Kilogram and Measurements of Mass and Force, Z. J. Jabbour et al., J. Res. Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. 106, 2001, 25–46 (3.5 MB PDF, here)

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Uncertainty Improvements of the NIST Electronic Kilogram, RL Steiner et al., Instrumentation and Measurement, IEEE Transactions on, 56 Issue 2, April 2007, 592–596

- ↑ Georgia Tech, “A Better Definition for the Kilogram?” 21 September 2007 (press release).

- ↑ NPL: Avogadro Project; Australian National Measurement Institute: Redefining the kilogram through the Avogadro constant; and Australian Centre for Precision Optics: The Avogadro Project

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 The German national metrology institute, known as the Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (PTB): Working group 1.24, Ion Accumulation

- ↑ General Conference on Weights and Measures, 22nd Meeting, October 2003 (3.2 MB ZIP file).

- ↑ The Caravan, Sept. 1–15, 2009: “Why the World is Losing Weight”

- ↑ "An initial measurement of Planck's constant using the NPL Mark II watt balance", I.A. Robinson et al., Metrologia 44 (2007), 427–440;

NPL: NPL Watt Balance - ↑ Joshua P Schwarz et al. (July–August 2001). "Hysteresis and Related Error Mechanisms in the NIST Watt Balance Experiment" (888 KB PDF). Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards and Technology 106 (4). http://nvl.nist.gov/pub/nistpubs/jres/106/4/j64schw.pdf.

B.N. Taylor et al. (1999). "On the redefinition of the kilogram". Metrologia 36: 63–64. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/36/1/11.

"Fundamental physical constants: ‘Energy Equivalents’ calculator". NIST. http://physics.nist.gov/cgi-bin/cuu/Convert?exp=0&num=1&From=kg&To=hz&Action=Convert+value+and+show+factor. - ↑ R. Steiner, Watts in the watt balance, NIST, 16 Oct. 2009.

- ↑ R. Steiner, No FG-5?, NIST, 30 Nov. 2007. “We rotate between about 4 resistance standards, transferring from the calibration lab to my lab every 2–6 weeks. Resistors do not transfer well, and sometimes shift at each transfer by 10 ppb or more.”

- ↑ NIST. "Beyond the kilogram: redefining the International System of Units". Press release. http://www.nist.gov/public_affairs/newsfromnist_beyond_the_kilogram.htm.

R. Steiner, A Watt Balance On Its Side, NIST, 24 September 2007. - ↑ BIPM: SI Brochure: Section 3.2, The kilogram

- ↑ BIPM: SI Brochure: Section 4.1, Non-SI units accepted for use with the SI, and units based on fundamental constants: Table 6

External links

| BIPM: The IPK in three nested bell jars | |

| NIST: K20, the US National Prototype Kilogram, resting on an egg crate fluorescent light panel | |

| BIPM: Steam cleaning a 1 kg prototype before a mass comparison | |

| BIPM: The IPK and its six sister copies in their vault | |

| The Age: Silicon sphere for the Avogadro Project | |

| NPL: The NPL’s Watt Balance project | |

| NIST: This particular Rueprecht Balance, an Austrian-made precision balance, was used by the NIST from 1945 until 1960 | |

| BIPM: The FB‑2 flexure-strip balance, the BIPM’s modern precision balance featuring a standard deviation of one ten-billionth of a kilogram (0.1 µg) | |

| BIPM: Mettler HK1000 balance, featuring 1 µg resolution and a 4 kg maximum mass. Also used by NIST and Sandia National Laboratories’ Primary Standards Laboratory | |

| Micro-g LaCoste: FG‑5 absolute gravimeter, (diagram), used in national laboratories to measure gravity to 2 µGal accuracy | |

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST): NIST Improves Accuracy of ‘Watt Balance’ Method for Defining the Kilogram

- The U.K.’s National Physical Laboratory (NPL): An overview of the problems with an artifact-based kilogram

- NPL: Avogadro Project

- NPL: NPL watt balance

- Metrology in France: Watt balance

- Australian National Measurement Institute: Redefining the kilogram through the Avogadro constant

- International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM): Home page

- NZZ Folio: What a kilogram really weighs

- NPL: What are the differences between mass, weight, force and load?

- BBC: Getting the measure of a kilogram

- NPR: This Kilogram Has A Weight-Loss Problem, an interview with National Institute of Standards and Technology physicist Richard Steiner

|

||||||||||||||||||||