Pichilemu

| Pichilemu Pichilemo |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| — City — | |||

|

|||

|

|||

| Nickname(s): Surf Capital (Capital del Surf) | |||

|

|||

Pichilemu

|

|||

| Coordinates: | |||

| Country | |||

| Region | O'Higgins | ||

| Province | Cardenal Caro | ||

| Settled | October 6, 1845 | ||

| Incorporated (city) | December 22, 1891 | ||

| Government | |||

| - Mayor | Marcelo Cabrera (2008–2009)[1][2] Roberto Córdova (2009–2012)[3] |

||

| Area | |||

| - Total | 9.7 km2 (3.7 sq mi) | ||

| Population (2002) | |||

| - Total | 12,392 | ||

| - Density | 16.54/km2 (42.8/sq mi) | ||

| Time zone | Chile Time (CLT)[4] (UTC-4) | ||

| - Summer (DST) | Chile Summer Time (CLST)[5] (UTC-3) | ||

| ZIP codes | 3220478 | ||

| Website | http://www.pichilemu.cl/ | ||

Pichilemu (Mapudungun: Small forest,[6] pronounced [pitʃiˈlemu] (![]() listen)), previously known as Pichilemo,[7] is a beach resort city in central Chile.[8] Pichilemu is the capital of Cardenal Caro Province,[9] and it is home to five historic monuments of Chile (Agustín Ross Cultural Centre, Agustín Ross Park, Pichilemu railway station, El Árbol tunnel, and Caballo de Agua) and was declared a Zona Típica ("Traditional Area" or "Heritage Site") by the National Monuments Council in 2004.[10] Pichilemu had 12,392 residents in 2002.[11]

listen)), previously known as Pichilemo,[7] is a beach resort city in central Chile.[8] Pichilemu is the capital of Cardenal Caro Province,[9] and it is home to five historic monuments of Chile (Agustín Ross Cultural Centre, Agustín Ross Park, Pichilemu railway station, El Árbol tunnel, and Caballo de Agua) and was declared a Zona Típica ("Traditional Area" or "Heritage Site") by the National Monuments Council in 2004.[10] Pichilemu had 12,392 residents in 2002.[11]

Pichilemu was founded December 22, 1891 by a decree of President Jorge Montt and Interior Minister Manuel José Irarrázabal.[12] It was conceived as a beach resort for upper-class Chileans by Agustín Ross Edwards, a Chilean politician and member of the Ross Edwards family.[13][14]

The city is part of District No. 35 and is in the ninth senatorial constituency of O'Higgins Region electoral division.[15] Pichilemu is home to the main beach in O'Higgins Region, and is a tourist destination for surfing, windsurfing and funboarding.[16]

Tourism is the main industry of the city,[17] but forestry and handicrafts are also important.[18] Pichilemu has many expansive dark sand beaches. Several surf championships take place in the city each year[19][20] at Punta de Lobos,[16] which according to Fodor's is "widely considered the best surfing in South America year-round."[21]

Contents |

History

-lámina_1.jpg)

The name Pichilemu comes from the Mapudungún words pichi (little) and lemu (forest).[6]

Pichilemu was inhabited by Promaucaes, a pre-Columbian tribal group, until the Spanish conquest of Chile.[22] They were hunter-gatherers and fishermen who lived primarily along the Cachapoal and Maule rivers.[22] During the colonial period, the remaining Promaucaes were assimilated into Chilean society through a process of hispanicization and mestization.[23]

Writer José Toribio Medina (1852–1930) spent most of his life in Colchagua Province. He owned properties in Chomedahue, Santa Cruz, and La Cartuja, San Francisco de Mostazal. He completed his first archeological investigations in Pichilemu. In 1908, he published Los Restos Indígenas de Pichilemu (English: Indigenous Remains of Pichilemu),[17][24] in which he stated:

| “ | The indians that the Spaniards found in that place [Pichilemu] undoubtfully were part of Promoucaes, and they must have formed part of the Topocalma encomienda, that was given in January 24, 1544 by Pedro de Valdivia to Juan Gómez de Almagro. Both facts are deduced from the text of the certificate of that encomienda: "I give to you Juan Gómez, said Valdivia, the cheftains called Palloquierbico, Topocalma and Gualauquén, along with their relatives and indians, that are [living] in the Promoucaes provinces, near the sea coast". | ” |

|

—José Toribio Medina, Los Restos Indígenas de Pichilemu (1908).[24] |

||

During the colonial and Republican periods, agriculture was promoted by the government. Many Chilean haciendas (estates) were successful during this time, including the Pichileminian San Antonio de Petrel,[17] where Cardinal José María Caro was born.[17] Hacienda El Puesto, owned by Basilio de Rojas y Fuentes, was located near Pichilemu.[25]

The area around Pichilemu was very densely populated, especially in Cáhuil, where there are salt deposits that were were exploited by natives. Pichilemu has had censuses taken since the 17th century. In 1778 a church was constructed in Ciruelos and designated a viceparroquia (vice parish). In 1864 it officially became a parroquia (parish).[18]

Ortúzar family

The area around Pichilemu was part of Estancias San Francisco de Pichilemu y San Antonio de Petrel, which was established in the 17th century. It was first called "Pichilemu" in 1873, and was described as a village.[18]

Some of the first land owners in the area were members of the Ortúzar family.[26] Daniel Ortúzar was one of the founders of the original village of Pichilemu.[26]

In 1872, President of Chile Aníbal Pinto commissioned the corvette captain Francisco Vidal Gormaz to perform a survey of the coast between Tumán Creek and Boca del Mataquito. He noted in his research that Matanzas, Sirenas, Pupuya, Los Piures, and Cáhuil were too open for ferries. He named Tumán, Topocalma, and Pichilemu as places with better hydrographic conditions. He concluded that Pichilemu was the best place to construct a ferry. In 1887, President José Manuel Balmaceda decreed Pichilemu as a minor dock.[27] The family of Ortúzar Cuevas from the San Antonio de Petrel Hacienda constructed the dock in 1875, which served as a fishing port for a few years.[18][28] Homes were built along the dock on what is now Ortúzar Avenue. Later, large land owners included Pedro Pavez Polanco and Hacienda of San Antonio de Petrel. These large land-holding families built historic homes and buildings over the years.[29]

During the 1891 Chilean Civil War, Daniel Ortúzar and the priest of Alcones transferred prisoners to and from Pichilemu via the dock.[30] The dock was burned during the war, and was later reconstructed and used until 1912, but never reached "port" status.[18][28]

Foundation

Lauriano Gaete and Ninfa Vargas founded Pichilemu in late 1891 after conceiving the design of the city with engineer Emilio Nichón. By decree of President Jorge Montt and his Interior Minister, Manuel José Irarrázabal, the city was officially established on December 22, 1891.[12] The first mayor of the city was José María Caro Martínez.[12] He formalized the city plan in 1894.[29] Pichilemu became the capital of Cardenal Caro Province, which is named after Cardinal José María Caro.[27]

Pichilemu belonged to the Department of Santa Cruz as part of Colchagua Province until approximately 1952.[31]

Agustín Ross

Agustín Ross Edwards, a Chilean writer, Member of Parliament, minister, and politician, was part of the Ross Edwards family which founded the newspaper El Mercurio in 1827.[14][32] Ross was administrator of Juana Ross de Edwards' estate, the Nancagua Hacienda, which was located near the city of Nancagua. Based on his European experiences, in 1885 he bought a 300-hectare (740-acre) tract of land and named it La Posada (English: The Inn), or Petren Fund. At the time, it was merely a set of thick-walled barracks.[10]

Agustín Ross turned Pichilemu into a summer resort town for affluent people from Santiago. He designed an urban setting that included a park and a forest of over 10 hectares (25 acres).[10][33] He transformed La Posada into a hotel (Great Hotel Pichilemu, later Hotel Ross, or Ross Hotel). He built the Ross Casino, several chalets, terraces, embankments, stone walls, a balcony facing the beach, and several large homes with building materials and furniture imported from France and England. However, Ross was not able to build the dock he had planned for the city.[34]

Agustín Ross died in 1926 in Viña del Mar. In 1935, Ross' successors ceded all of Ross' constructions (streets, avenues, squares, seven hectares of forests, the park in front of the hotel, the perrons, and the terraces) to the Municipality of Pichilemu, on the condition that the municipality hold them for recreation and public access.[10] The Ross Casino (1905) and Agustín Ross Park (1885) have since become an important part of the city, and have been declared Monumento Histórico by the National Monuments Council.[10]

2010 earthquakes

The city was severely affected by the February 27, 2010 Chile earthquake, and its subsequent tsunami provoked massive destruction near the coast.[35] On March 11, 2010 at 11:39:48 (14:39:48 UTC), a magnitude 6.9 earthquake occurred 41 kilometres (25 mi) southwest of Pichilemu,[36][37] killing at least two people.[38]

Geography

Pichilemu is located 126 kilometres (78 mi) west of San Fernando, Chile, on the coast of the Pacific Ocean.[8] It is within a three-hour drive of the Andes Mountains.[39] It is near the Cordillera de la Costa (Coastal Mountain Range) which rises to 2,000 metres (6,562 ft) in altitude.[40]

Although the majority of the forest areas around Pichilemu are covered with pine and eucalyptus plantations, a native forest (now the Municipal Forest) remains. It contains species such as Litres, Quillayes, Boldos, Espinos, and Peumos.[29]

Pichilemu is bordered by Litueche to the north, Paredones to the south, and Marchigüe and Pumanque to the east. To the west lies the Pacific Ocean.[41] Pichilemu covers an area of 9.70 square kilometres (3.75 sq mi).[11]

| Litueche | Pumanque | |

| Pacific Ocean |  |

Marchigüe |

| Paredones | Lolol |

Nearby bodies of water include the Nilahue Estuary, which flows to Cáhuil Lagoon, Petrel Estuary, which flows to Petrel Lagoon, and El Barro, El Bajel, and El Ancho lagoons, the latter of which provides the city with drinking water.[18]

Climate

| Climate data for Pichilemu | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 82.4 (28) |

78.8 (26) |

78.8 (26) |

75.2 (24) |

64.4 (18) |

59 (15) |

55.4 (13) |

57.2 (14) |

60.8 (16) |

68 (20) |

64.4 (18) |

71.6 (22) |

82.4 (28) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 60.8 (16) |

60.8 (16) |

60.8 (16) |

57.2 (14) |

53.6 (12) |

50 (10) |

46.4 (8) |

48.2 (9) |

46.4 (8) |

51.8 (11) |

53.6 (12) |

57.2 (14) |

46.4 (8) |

| Source: WindGuru | |||||||||||||

Pichilemu experiences a Mediterranean climate, with winter rains which reach 700 millimetres (28 in).[18][42] The rest of the year is dry, often windy, and sometimes with coastal fog. Occasionally the city receives winds as high as 150 kilometres per hour (93 mph).[43]

Demographics

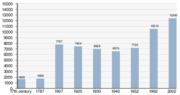

By the 17th century, Pichilemu had 1,468 inhabitants.[44] In 1787, Pichilemu held 1,688 inhabitants,[44] and the population rose to 7,787 inhabitants by 1907.[31] From there onward, the city's population progressively decreased: 7,424 in 1920; 6,929 in 1930; and 6,570 in 1940.[31] In 1952, the city's population increased to 7,150 inhabitants; in 1992, 10,510.[31] As of the 2002 census, 12,392 people resided in the city. The census classified 9,459 people (76.3%) as living in an urban area and 2,933 people (23.7%) as living in a rural area, with 6,440 men (52.0%) and 5,952 women (48.0%).[11] According to the CASEN 2002 census, 544 inhabitants (4.4%) of the population live in extreme poverty compared to the average in the greater O'Higgins Region of 4.5%, and 1,946 inhabitants (15.7%) live in mild poverty, compared to the regional average of 16.1%.[45]

Government and politics

Pichilemu, along with the communes of Placilla, Nancagua, Chépica, Santa Cruz, Pumanque, Palmilla, Peralillo, Navidad, Lolol, Litueche, La Estrella, Marchihue, and Paredones, is part of Electoral District No. 35 and belongs to the 9th Senatorial Constituency (O'Higgins) of the electoral divisions of Chile.[15]

The city consists of an urban center and 23 rural villages: Alto Ramírez, Barrancas, Cáhuil, Cardonal de Panilonco, Ciruelos, Cóguil, Espinillo, La Aguada, la Palmilla, La Villa, La Plaza, Las Comillas, Pueblo de Viudas, Quebrada del Nuevo Reino, Pañul, Rodeillo, Tanumé, Petrel,[46] San Miguel de la Palma,[47] Las Garzas,[48] and Alto Colorado.[18][49]

José María Caro Martínez was elected the first Mayor of Pichilemu in 1894, and held the office until 1905.[12] He was the father of José María Caro, the first Chilean Cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church. Caro said he remembers Pichilemu had only two humble residences during those years.[50]

Jorge Vargas was Mayor of Pichilemu for over 10 years, from 1997[51][52][53] to 2007,[54] until he was accused of theft.[54][55] He was succeeded by Victor Rojas, who was later accused of the same crime.[56]

The last elected mayor was Marcelo Cabrera; he was elected in 2008 with 42.08% of the vote.[57] He served from May[2] to August 2009 when he was disqualified from holding public office because he was convicted of adulterating ballots.[58] The municipal council elected Roberto Córdova as new mayor on September 9, 2009.[59] From 2008 until 2010, the councillors are Aldo Polanco Contreras, Andrea Aranda Escudero, Viviana Parraguez Ulloa, Patricio Morales, Juan Cornejo Vargas and Marta Urzúa Púa.[59]

Between 2007 and 2009, Pichilemu had seven mayors,[1][54] four of whom were temporary.[3]

Culture and economy

Tourism is the main industry of Pichilemu, especially in the urban center and some rural areas such as Cáhuil and Ciruelos. Forestry, mainly pine and eucalyptus, is another major industry. The area is also known for handicrafts.[18] Fishing is not very important to O'Higgins Region, due to unsuitable coastlines; it is common in Pichilemu, Bucalemu, and Navidad.[17]

Pichilemu has a clay deposit in the Pañul area.[17] According to archaeological investigations, pottery was first manufactured in the area circa 300 BCE. It is still a stalwart today – Ciruelos and El Copao are well-known for the pottery they create.[60]

Dr. Aureliano Oyarzún investigated pre-Ceramic middens from Pichilemu and Cahuil. He published the book Crónicas de Pichilemu-Cahuil (Chronicles of Pichilemu and Cahuil) in 1957.[61] Tomás Guevara published in two volumes of Historia de Chile, Chile Prehispánico in 1929, which discuss the indigenous center of Apalta, Pichilemu middens, Malloa petroglyphs, a stone cup from Nancagua, and pottery finds in Peralillo.[17]

In Cáhuil Lagoon, a type of boat called caballito de mar, made with the totora plant from Laguna del Perro, was used by natives until the twentieth century.[62]

National Monuments

Pichilemu was declared a Typical Zone by the National Monuments Council of Chile, by decree No. 1097 on December 22, 2004.[10]

The city is home to five other National Monuments: Ross Park, Ross Casino, El Árbol Tunnel, Pichilemu railway station, and Caballo de Agua.[63]

Ross Casino

The old Ross Casino, currently the Cultural Centre, is located on Agustín Ross Avenue in front of Ross Park (). The three-floor casino was constructed with imported materials in early 1900s by Agustín Ross. It originally housed the first mail and telegraph service and a large store. The first casino in Chile was opened in this building on January 20, 1906.[34][50][64] It operated until 1932, when the Viña del Mar Casino was opened.[65]

The building was renovated and reopened in 2009 as a cultural arts center. It currently houses several gallery spaces and the public library. During its restoration, workers found many historical artifacts, including a copy of Las Últimas Noticias from February 1941 when Ross Casino served as a hotel; an American telephone battery dating from the period of 1909 to 1915; and a tile from the casino's ceiling signed by workers during the building's construction in 1914.[66]

Ross Park and Hotel

Ross Park was created by Agustín Ross in 1885, and remodeled in December 1987.

| “ | When he came here, there was nothing. Just a pair of houses, or less. He gave a form to the town, he gave it European looks. Look these balustrades which decorate the slope or the ones which border the park, are the same which Mr. Agustin saw on Biarritz. | ” |

|

— Jaime Parra, current administrator of Agustín Ross Hotel.[43]

|

The park is located on Agustín Ross Avenue, in front of Ross Casino (). The hotel was originally named Gran Hotel Pichilemu (Great Hotel Pichilemu).[43] The once grand Ross Hotel was constructed at the same time, and is one of the oldest hotels in Chile. Although it is still partially open to guests, it is in a state of disrepair.[10]

The park boasts 100-year-old native Chilean palms (Phoenix canariensis) and many green spaces. It was recently restored, and is now a popular walking destination.[67][68]

Both the park and the former casino were named National Monuments on February 25, 1988.[67][69]

Railway station

Ex Estación de Ferrocarriles, the old railway station, is a wooden building constructed around 1925.[50] It is in front of Petrel Lagoon, near Daniel Ortúzar Avenue (). It remained in operation until the 1990s, and became a National Monument on September 16, 1994.[69] It has since become an arts and culture center and tourism information office.[67] It exhibits decorative and practical objects from the 1920s, and features many old clothes.[67]

Railroad history

357 kilometres (222 mi) of railway lines were constructed in the O'Higgins Region, but only 161 kilometres (100 mi) still exist.[70] The 119 kilometres (74 mi) San Fernando–Pichilemu section was constructed between 1869 and 1926.[50] Passenger services operated on the line until 1986 and freight services were operational until 1995.[70] In 2006, the Peralillo–Pichilemu section was removed completely.[70][71][72]

Important places

Pichilemu has many places of interest to tourists. The Bosque Municipal (Municipal Forest) was donated by the Ross family in 1935. The main access to the forest is in front of Ross Casino, near Paseo el Sol (a dirt road). The forest has a footpath surrounded by palms, pines, and many other varieties of trees.[73]

Conchal Indígena (Indigenous Midden) is an archaeological site of pre-hispanic times. It is located on the site of an ancient fishing village 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) from Punta de Lobos and 0.3 kilometres (0.19 mi) south of Los Curas Lagoon.[67][74] Laguna Los Curas (Los Curas Lagoon) is a natural area used for eco-tourist activities such as fishing located 7 kilometres (4.3 mi) south of Pichilemu. Another lagoon, del Perro (The Dog's Lagoon) is located 8.5 kilometres (5.3 mi) south of Pichilemu. It is used for recreational activities.[67][74]

Los Navegantes is a neighborhood in Pichilemu, approximately 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi) in size, which was founded in 1997. After five years of construction, around 30 houses were built. It has a small sports court where residents can play football, basketball, and tennis.

Laguna El Alto (El Alto Lagoon) is a small, rain-fed lagoon located at Chorrillos Beach that is often used for camping and picnics. The lagoon is an hour and a half drive from Pichilemu, traveling to the north by Chorrillos beach.[67] Poza del Encanto is a lagoon located 30 kilometres (19 mi) from Pichilemu. It is home to a large variety of native fauna.[75] Estero Nilahue (Nilahue Lagoon) is located 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) from Pichilemu. It has several beaches, including El Bronce, El Maquí, and Laguna El Vado.[76]

St. Andrew Church is located in Ciruelos, 13 kilometres (8.1 mi) from Pichilemu. It was constructed in 1779, and its altar was built in the 1940s. It has a harmonium, confessional boxes, and ancient images of saints. Its original image of St. Andrew was made of papier mache. The old parish was created by Archbishop Rafael Valentín Valdivieso in 1864. Cardinal José María Caro was baptized there. The feast day of St. Andrew is celebrated every November 30 at the church.[67][74]

Museo del Niño Rural (the Rural Kid Museum) was created as an initiative of teacher Carlos Leyton and his students. It is a modern building that utilises traditional architecture. Three rooms contain a collection of stone tools, arrowheads, and clay tools made by the indigenous people of the region. Also on display are domestic tools from early colonists.[77]

El Copao is a hamlet located 14 kilometres (8.7 mi) east of Pichilemu. Its main industry is domestic pottery production, using clay as a raw material.[67] Pañul (pronounced Pagnul) is a settlement located 17 kilometres (11 mi) from Pichilemu. Its name in Mapudungun means "medicinal herb". Pañul produces pottery made with locally obtained clay.[78] Cáhuil is a small settlement located 13 kilometres (8.1 mi)[67] south of Pichilemu. Its name in Mapudungun means "parrot place". Cahuil lagoon is used for fishing, swimming, and kayaking; kiteboarding lessons are offered on the lagoon. The bridge is open to motor traffic, and has a view of the Cahuil zone. The bridge provides access to Curicó, Lolol, Bucalemu, and other nearby places.[75]

Beaches

Pichilemu has many expansive dark sand beaches.[79] The water is cool year-round, and many tourists choose to swim at the shore break during the summer months.[79] Common activities include bodyboarding, surfing, windsurfing, and kitesurfing.[25][80]

The northernmost of the beaches is Playa San Antonio or Playa Principal (San Antonio Beach or Main Beach), which is in front of Ross Park. It is popular for surfing. Near the beach and at Ross Park are balustrades and long stairs dating from the early 1900s. There is a balcony over the rocks at the southern end of the beach.[67]

Playa Las Terrazas (The Terraces Beach) is busiest during the summer months. Several surf schools, La Ola Perfecta and Lobos del Pacífico, are located nearby, as is the fish market at Fishermen Creek.[45] Located south of the town and around the other side of the Puntilla, Playa Infiernillo (Little Hell Beach) is rocky and has tide-pools. This area is used for fishing.[45] South of Infiernillo is Playa Hermosa (Beautiful Beach), which is popular for walking and fishing.[67]

Further south, 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) from Pichilemu, Punta de Lobos features a beach sheltered from the southern winds. It is an increasingly popular destination for tourists and surfers.[80] Several surf contests are held there, including an international big-wave contest during the Chilean fall. The size of waves varies throughout the year. Large swells in fall and winter can reach heights of up to 15 metres (49 ft). It is widely considered one of the best beaches for surfing worldwide.[79]

Surfing

Surfing is a tourist attraction, particularly at Punta de Lobos.[81][82] According to Fodor's travel guide,[21]

[Pichilemu] is Chile's prime surf spot, and people come from around the world to test their skills. ... [Punta de Lobos] is widely considered the best surfing in South America year-round.—Fodor's Chile: Including Argentine Patagonia

Every October and December, an International Championship of Surf is held at La Puntilla Beach.[83] Punta de Lobos hosts the Campeonato Nacional de Surf (National Surfing Championship) every summer.[33]

Media

The local newspaper, called El Expreso de la Costa,[84] has a circulation area that covers most of Cardenal Caro Province. It is directed by Félix Calderón.[84] There is an online newspaper in Spanish called Pichilemu News.[85] It is edited by Washington Saldías, former councillor of the city.[85] The magazine Hola Vecino covers most of O'Higgins Region and is directed by Francisco Espejo.[84]

Radio services come from Radio Entre Olas,[84] Radio Atardecer,[84] Radio Somos Pichilemu (directed by former Mayor Jorge Vargas González), and Radio Isla.[84]

Education

Pichilemu has many schools, including: Charly's School, a primary and secondary school in El Llano;[86] Escuela Digna Camilo Aguilar (Digna Camilo Aguilar School), a primary school near Charly's School;[87] Colegio Libertadores (Liberators School), a primary school in Infiernillo; Colegio Preciosa Sangre (Precious Blood School), a primary and secondary school near El Llano; Colegio Divino Maestro (Divine Master School), a primary school near Pueblo de Viudas; and Escuela Pueblo de Viudas (Pueblo de Viudas School), a primary school in Pueblo de Viudas.[88] Other schools include Liceo Agustín Ross Edwards (Agustín Ross Edwards High School), a secondary school in El Llano, near Escuela Digna Camilo Aguilar and Charly's School, and Jardín Amanecer (Dawn Garden), a kindergarten school in El Llano.[88]

In 2009, a cheerleading team from Colegio Preciosa Sangre participated in a championship in the United States, and received awards for their efforts.[89]

Important dates

| Date[90] | Festivity[90] | Place[90] |

|---|---|---|

| December 31 – January 1 | Año Nuevo Junto al Mar (New Year with the Sea) | Agustín Ross Park, in front of the Agustín Ross Cultural Centre |

| February 6 – February 19 | Semana Pichilemina (Pichileminian Week) | Pichilemu |

| February 16 – February 21 | Fiesta Costumbrista Folclore Junto al Mar (Folklore and Local Customs Festival with the Sea) | Arturo Prat Square, Pichilemu |

| February 25 – February 26 | Trilla a Yegua Suelta (Threshing with Horses) | La Puntilla, Pichilemu |

| Between March and April (date varies) | Semana Santa en Pichilemu (Passion Week in Pichilemu) | Inmaculada Concepción Parish, Pichilemu |

| April 9 | Muestra Nacional de Cueca (National Cueca Demonstration) | Municipal Gymnasium of Pichilemu |

| September 17 – September 19 | Fiestas Patrias ("Independence Day of Chile" or "National Holiday") | Pichilemu |

| September 18 – September 21 | Campeonato Estudiantil de Surf (Student Surf Championship) | La Puntilla Beach and Punta de Lobos |

| November 30 | Feast day of Saint Andrew | Ciruelos |

| December 8 | Fiesta de la Purísima (Inmaculate Conception Festival) | Inmaculada Concepción Parish, Pichilemu |

See also

- List of cities in Chile

- People from Pichilemu

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 El Rancahuaso Team (2009-02-17). "Hasta 3 años de Cárcel arriesga el Alcalde de Pichilemu" (in Spanish). El Rancahuaso. http://www.elrancahuaso.cl/admin/render/noticia/17884. Retrieved 2009-12-04.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 El Rancahuaso Correspondents (2009-05-19). "Marcelo Cabrera asumió como alcalde de Pichilemu" (in Spanish). El Rancahuaso. http://www.elrancahuaso.cl/admin/render/noticia/19000. Retrieved 2009-12-04.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Washington Saldías (2009-09-01). "Alcalde titular "Habemus" en Pichilemu: Roberto Córdova elegido trans resolución del Tricel" (in Spanish). PichilemuNews.cl. http://pichilemunews.blogcindario.com/2009/09/03107-alcalde-titular-habemus-en-pichilemu-roberto-cordova-carreno-elegido-tras-resolucion-del-tricel.html. Retrieved 2009-12-04.

- ↑ "Chile Time". World-Time-Zones.org. http://www.world-time-zones.org/zones/chile-time.htm. Retrieved 2007-05-05.

- ↑ "Chile Summer Time". World-Time-Zones.org. http://www.world-time-zones.org/zones/chile-summer-time.htm. Retrieved 2007-05-05.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Diccionario Mapuche" (in Spanish). Escolares.net. http://www.escolares.net/descripcion.php?ide=563. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- ↑ Pichilemo (Puerto de) entry at Diccionario Geográfico de la República de Chile (1899) at Wikisource, by Francisco Astaburuaga Cienfuegos. (Spanish)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Pichilemu". Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2008. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/459359/Pichilemu.

- ↑ "Cardenal Caro" (in Spanish). VI.cl. http://www.vi.cl/secciones/turismo/cardenal_caro.html. Retrieved 2009-12-04.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 Chrisitian Matzner (2004-12-22). "Sector de Pichilemu". National Monuments Council. http://www.monumentos.cl/OpenSupport_Monumento/asp/PopUpFicha/ficha_publica.asp?monumento=595. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 National Statistics Institute of Chile. "O'Higgins Region Statistics 2002 census" (in Spanish). http://alerce.ine.cl/canales/chile_estadistico/censos_poblacion_vivienda/censo2002/mapa_interactivo/sexta.swf. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Washington Saldías (August 2, 2007). "Alcaldes, regidores y concejales de la comuna de Pichilemu" (in Spanish). Pichilemu News. http://pichilemunews.blogcindario.com/2007/08/01679-alcaldes-regidores-y-concejales-de-la-comuna-de-pichilemu.html. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- ↑ Millas, Hernán (2005) (in Spanish). La Sagrada Familia. Editorial Planeta. ISBN 956-247-381-3.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Washington Saldías (5 February 2010). "Don Agustín Ross Edwards: A 166 años del natalicio del impulsor del balneario de Pichilemu" (in Spanish). Pichilemu News. http://pichilemunews.blogcindario.com/2010/02/03270-don-agustin-ross-edwards-a-166-anos-del-natalicio-del-impulsor-del-balneario-de-pichilemu.html. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Chile Government. "Sistema de Despliegue de Cómputos — Ministerio del Interior" (in Spanish). Ministerio del Interior. http://www.elecciones.gov.cl/Sitio2009/p-cs9.htm. Retrieved 2010-01-12.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Surfistas esperan "la gran ola" en Pichilemu" (in Spanish). Chilevisión. http://www.chilevision.cl/home/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=169249&Itemid=81. Retrieved 2010-01-06. (Video)

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 17.6 Carmen del Río Pereira Blanca Tagle Arduengo (2009) (in Spanish). Región de O'Higgins: Breve relación del patrimonio natural y cultural. Pro-O'Higgins.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 18.6 18.7 18.8 Carla Ramírez Lechuga (2007). "Edificio Consistorial I. Municipalidad de Pichilemu" (in Spanish). University of Chile. http://www.cybertesis.cl/tesis/uchile/2004/ramirez_c2/sources/ramirez_c2.pdf. Retrieved 2010-04-14. (thesis)

- ↑ Angela Neira (2 April 2010). "Pichilemu convoca a mejores surfistas del mundo para participar en evento extremo" (in Spanish). La Tercera. http://latercera.com/contenido/680_238850_9.shtml. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- ↑ Carlos Jimeno Ocares (1 August 2008). "Mundial de Surf en Olas Gigantes entraría al agua la próxima semana" (in Spanish). El Mercurio. http://www.emol.com/noticias/deportes/detalle/detallenoticias.asp?idnoticia=315673. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Fodor's (2008). Taplan, Alan. ed. Fodor's Chile: Including Argentine Patagonia. New York: Random House. p. 218. ISBN 978-1-4000-1967-0. http://books.google.com/?id=x7igKTnjveAC.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Carmen del Río Pereira - Blanca Tagle Arduengo. "Historia regional desde la llegada del español hasta el siglo XIX : Los pueblos precolombinos" (in Spanish). Pro-O'Higgins. http://www.pro-ohiggins.cl/libro/cuerpo/2_2_1.html. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ↑ Domingo Faustino Sarmiento (1915) (in Spanish). Conflicto y armonías de las razas en América. Buenos Aires : "La Cultura Argentina". http://www.archive.org/details/conflictoyarmo00sarm. Retrieved 2009-12-16.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 José Toribio Medina (1908) (in Spanish). Los restos indígenas de Pichilemu. Imprenta Cervantes. http://www.archive.org/details/losrestosindgen00medigoog. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "Al Compás de las Olas" (in Spanish). Chile.com. http://www.chile.com/secciones/ver_seccion.php?id=25596. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 "Reseña Histórica de Pichilemu" (in Spanish). DePichilemu. http://www.depichilemu.cl/historia.htm. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 León Vargas, Victor (1996) (in Spanish). En Nuestra Tierra Huasa de Colchagua. Energía y Motores.. Santiago de Chile: Ed. Museo de Colchagua – Impresos Universitaria, S.A..

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Washington Saldías (2006-11-16). "Puerto en Pichilemu: Histórica Bitácora del Engaño" (in Spanish). Pichilemu News. http://pichilemunews.blogcindario.com/2006/11/01068-puerto-en-pichilemu-historica-bitacora-del-engano.html. Retrieved 2010-01-06.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Marisol D. Muñoz Hernandez. "AO501-1 Taller de Diseño Arquitectonico 1 2010, Semestre Otoño" (in Spanish). Universidad de Chile. https://www.u-cursos.cl/fau/2010/1/AO501/1/material_alumnos/objeto/10442. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ↑ Jorge Núñez P. (May 2003) (in Spanish). 1891, crónica de la guerra civil. ISBN 956-282-527-2. http://books.google.com/?id=n71SIc6IZE8C&pg=PA38&lpg=PA38&dq=pichilemu+guerra+civil+1891&q=Pichilemu. Retrieved 2009-12-16.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 Carmen del Río Pereira and Blanca Tagle Arduengo (in Spanish). Región de O'Higgins: Breve Relación del Patrimonio Natural y Cultural. http://www.pro-ohiggins.cl/libro/cuerpo/3_1_4.html. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- ↑ "Agustín Ross Edwards - Senador" (in Spanish). Biblioteca Nacional de Chile. http://biografias.bcn.cl/pags/biografias/detalle_par.php?id=712. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Charlotte Beech, Jolyon Attwooll, Thomas Kohnstamm, and Andrew Dean Nystrom (2006-05-01). Chile and Easter Island. Footscray, Victoria, Australia: Lonely Planet. ISBN 9781740599979. http://books.google.com/?id=mw0KeQWVtsEC&pg=PT138#v=onepage&q=.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 "Casino (antiguo) de Pichilemu y los Jardínes del Parque Agustin Ross" (in Spanish). National Monuments Council. http://www.monumentos.cl/OpenSupport_Monumento/asp/PopUpFicha/ficha_publica.asp?monumento=1173. Retrieved 2009-12-06.

- ↑ "Pichilemu queda devastado tras el tsunami que afectó a la zona costera" (in Spanish). Radio Bío Bío. 2 March 2010. http://www.radiobiobio.cl/2010/03/02/pichilemu-queda-devastado-tras-el-tsunami-que-afecto-a-la-zona-costera/. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- ↑ "Informe de Sismo." (in Spanish). University of Chile. 11 March 2010. http://sismologia.cl/informe.php?id=20100311143929. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ↑ "Magnitude 6.9 - LIBERTADOR O'HIGGINS, CHILE". USGS. 11 March 2010. http://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/recenteqsww/Quakes/us2010tsa6.php. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ↑ "Hombre fallece en Talca de un paro cardíaco en medio de fuertes réplicas" (in Spanish). La Tercera. 11 March 2010. http://www.latercera.com/contenido/680_233172_9.shtml. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- ↑ "Pichilemu to San Fernando". Google Maps Chile. http://maps.google.cl/maps?f=d&source=s_d&hl=es&geocode=&saddr=pichilemu&daddr=san+fernando&sll=-34.584006,-70.987426&sspn=0.065435,0.154324&g=san+fernando&ie=UTF8&z=10. Retrieved 2009-12-16.

- ↑ "Relieve Región Libertador B. O'Higgins". Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile. http://siit2.bcn.cl/nuestropais/region6/relieve.htm. Retrieved 8 August 2010.

- ↑ Pichilemu.cl. "Pichilemu antes" (in Spanish). http://www.pichilemu.cl/turismo/historia/animacion/Pichilemu%20antes.exe. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- ↑ "Clima de Chile Región Libertador Gral. Bernardo O'Higgins" (in Spanish). Castor y Polux Ltda.. http://www.mapasdechile.com/clima_region06/index.htm. Retrieved 2009-12-06.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 Revista Sábado, El Mercurio. "Balnearios con Historia (III)" (in Spanish). http://melisa-recorridoporlasextaregion.blogspot.com/2008/01/el-que-fuera-el-ms-glamoroso-de-los.html. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 Washington Saldías (2009-11-11). "Censo de 1787: La Superintendencia y el Diputado de Cáhuil, José González" (in Spanish). PichilemuNews. http://pichilemunews.blogcindario.com/2009/11/03185-censo-de-1787-la-superintendencia-y-el-diputado-de-cahuil-jose-gonzalez.html. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 "PICHILEMU: Historia, estadísticas, mapas" (in Spanish). Mi Balcón. http://mibalcon.cl/vi-reg/hist156.htm. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- ↑ Petrel entry at Diccionario Geográfico de la República de Chile (1899) at Wikisource, by Francisco Astaburuaga Cienfuegos. (Spanish)

- ↑ San Miguel de la Palma entry at Diccionario Geográfico de la República de Chile (1899) at Wikisource, by Francisco Astaburuaga Cienfuegos. (Spanish)

- ↑ Garzas (Las) entry at Diccionario Geográfico de la República de Chile (1899) at Wikisource, by Francisco Astaburuaga Cienfuegos. (Spanish)

- ↑ Alto Colorado entry at Diccionario Geográfico de la República de Chile (1899) at Wikisource, by Francisco Astaburuaga Cienfuegos. (Spanish)

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 50.3 Antonio Saldías González (1990) (in Spanish). Pichilemu: Mis fuentes de información. El Promoucae. http://www.google.com/books?id=KfwbAAAAIAAJ. Retrieved 2010-01-12.

- ↑ "Votación Candidatos por Comuna Pichilemu Municipales 1996" (in Spanish). Ministerio del Interior. http://elecciones.gob.cl/SitioHistorico/paginas/1996/municipales/comunas/candidatos/total/4801.htm. Retrieved 2009-12-15.

- ↑ "Votación Candidatos por Comuna Pichilemu Municipales 2000" (in Spanish). Ministerio del Interior. http://elecciones.gob.cl/SitioHistorico/paginas/2000/municipales/comunas/candidatos/total/4801.htm. Retrieved 2009-12-15.

- ↑ "Votación Candidatos por Comuna Pichilemu Alcaldes 2004" (in Spanish). Ministerio del Interior. http://elecciones.gob.cl/SitioHistorico/paginas/2004/alcaldes/comunas/candidatos/total/4801.htm. Retrieved 2009-12-15.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 Washington Saldías (2007-06-07). "Alcalde de Pichilemu, Jorge Vargas, definitivamente culpable del delito de cohecho". Pichilemu News. http://pichilemunews.blogcindario.com/2007/06/01582-alcalde-de-pichilemu-jorge-vargas-definitivamente-culpable-del-delito-de-cohecho.html. Retrieved 2009-12-15.

- ↑ "Pichilemu: Querella por mal uso de fondos municipales" (in Spanish). El Mercurio. May 3, 2003. http://diario.elmercurio.cl/detalle/index.asp?id={aa0b838a-92e3-40b6-bb6e-1448c391fbf7}. Retrieved 2010-01-05.

- ↑ "Preso alcalde de Pichilemu acusado de inducción al falso testimonio". La Cuarta. 2006-03-22. http://www.lacuarta.cl/diario/2006/03/22/22.07.4a.CRO.PICHILEMU.html. Retrieved 2010-01-05.

- ↑ "Votación Candidatos por Comuna Pichilemu Alcaldes 2008" (in Spanish). Ministerio del Interior. http://elecciones.gob.cl/SitioHistorico/paginas/2008/alcaldes/comunas/candidatos/total/4801.htm. Retrieved 2009-12-15.

- ↑ El Rancahuaso Correspondents (2009-08-19). "¡Increíble!, Pichilemu otra vez se quedó sin alcalde" (in Spanish). El Rancahuaso. http://www.elrancahuaso.cl/admin/render/noticia/20179. Retrieved 2009-12-15.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 "Autoridades" (in Spanish). Pichilemu. http://pichilemu.cl/mun.php. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- ↑ Carmen del Río and M. Blanca Tagle (1998) (in Spanish). Una aproximación a nuestras raíces indígenas. Santiago de Chile: Editorial Platero.

- ↑ Oyarzún, Aureliano (1957) (in Spanish). Crónicas de Pichilemu-Cahuil. Imprenta Universitaria, Publicaciones del Museo de Etnología y Antropología de Chile, Nº 4 and 5, Year I.

- ↑ Szmulewicz E., Pablo (1984) (in Spanish). Etnohistoria de la costa central de Chile. Memoria Arqueología, U. de Chile.

- ↑ Washington Saldías (2008-05-22). "Cinco Monumentos Nacionales, Una Zona Típica en Pichilemu y el Día del Patrimonio Nacional" (in Spanish). PichilemuNews.cl. http://pichilemunews.blogcindario.com/2008/05/02263-cinco-monumentos-nacionales-una-zona-tipica-en-pichilemu-y-el-dia-del-patrimonio-nacional.html. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- ↑ Chile.com. "Pichilemu" (in Spanish). Chile.com. http://www.chile.com/tpl/articulo/detalle/ver.tpl?cod_articulo=97835. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- ↑ Washington Saldías (2001-01-14). "Identidad local y Casino Ross de Pichilemu" (in Spanish). Pichilemu News. http://pichilemunews.blogcindario.com/2007/01/01231-identidad-local-y-casino-ross-de-pichilemu.html. Retrieved 2010-07-05.

- ↑ Beatriz Valenzuela (2007-10-29). "Hallazgos históricos en la obra de restauración del ex casino Ross de Pichilemu" (in Spanish). El Rancahuaso. http://www.elrancahuaso.cl/admin/render/noticia/11636. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- ↑ 67.00 67.01 67.02 67.03 67.04 67.05 67.06 67.07 67.08 67.09 67.10 67.11 María José Muñoz (2007-02-24). "Atractivos de nuestra región. Hoy: Pichilemu" (in Spanish). El Rancahuaso. http://www.elrancahuaso.cl/admin/render/noticia/7987. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- ↑ "VI Región Playas" (in Spanish). Chile.com. http://www.chile.com/tpl/articulo/detalle/ver.tpl?cod_articulo=1146. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 "Monumentos Nacionales de la VI Región" (in Spanish). VI.cl. http://www.vi.cl/secciones/turismo/monumentos.html. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 70.2 Benedicto González (2007-12-02). "Historia del ferrocarril San Fernando a Pichilemu" (in Spanish). PichilemuNews.cl. http://pichilemunews.blogcindario.com/2007/12/01907-historia-del-ferrocarril-san-fernando-a-pichilemu.html. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- ↑ Juan Cornejo Acuña & Juan Cornejo Torrealba (2007) (in Spanish). Historia del Ferrocarril San Fernando a Pichilemu: 1869–2007. Santiago. http://www.amigosdeltren.cl/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=281&Itemid=241.

- ↑ "Historia del Ferrocarril San Fernando a Pichilemu" (in Spanish). De Colchagua. http://www.decolchagua.cl/modules.php?name=News&file=article&sid=4349. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- ↑ "Atractivos Turísticos Cardenal Caro". De Colchagua. http://www.decolchagua.cl/secciones/turismo/cardenal_caro.html. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 "Cardenal Caro" (in Spanish). VI.cl. http://www.vi.cl/secciones/turismo/cardenal_caro.html. Retrieved 2009-12-16.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 "Lugares" (in Spanish). Pichilemu.net. http://www.pichilemu.net/Link/lugar.htm. Retrieved 2009-12-16.

- ↑ El Rancahuaso Staff (April 2009). "Los Imperdibles de Pichilemu". El Rancahuaso. http://www.elrancahuaso.cl/admin/render/noticia/17439&print=true. Retrieved 8 August 2010.

- ↑ "Museo "Del niño rural"" (in Spanish). VI.cl. http://www.vi.cl/museosycasaspatronales/museociruelos. Retrieved 2009-12-16.

- ↑ "Pañul" (in Spanish). DePichilemu. http://www.depichilemu.cl/panul.htm. Retrieved 2009-12-16.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 79.2 "Pichilemu | "Nuevas formas de expresarse, comunicarse y hacer arte en la red" Aulas hermanas | Educasitios" (in Spanish). educ.ar. http://educasitios.educ.ar/grupo1176/?q=node/52. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 "Surfin' in Pichilemu" (in Spanish). Pichilemu's official website. http://www.pichilemu.cl/turismo/surf/Ingles/. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- ↑ Washington Saldías (2009-08-31). "Tercer Campeonato Estudiantil de Surf 2009: todo un éxito" (in Spanish). PichilemuNews.cl. http://pichilemunews.blogcindario.com/2009/08/03105-tercer-campeonato-estudiantil-de-surf-2009-todo-un-exito.html. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- ↑ "3° Campeonato Estudiantil de Surf" (in Spanish). Cámara de Turismo de Pichilemu. http://www.camaraturismopichilemu.cl/Campeonato2009.htm. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- ↑ "Pichilemu" (in Spanish). VI.cl. http://www.vi.cl/ciudadesyatractivos/pichilemu. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 84.2 84.3 84.4 84.5 "prensa regional – Gobierno Regional O'Higgins" (in Spanish). O'Higgins Region Government. 2007. http://www.goreohiggins.cl/LISTADOPRENSA2007.xls. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 "Quienes Somos" (in Spanish). Pichilemu News. http://www.pichilemunews.cl/_sitios/_colaboradores/somos.html. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- ↑ "Ficha Establecimiento (Charly's School)" (in Spanish). SIMCE. http://simce.cl/simce/index.php?id=228&iRBD=15522&iVRBD=5&iNivel=0&iAnio=2008. Retrieved 11 July 2010.

- ↑ "Ficha Establecimiento (Digna Camilo Aguilar)" (in Spanish). SIMCE. http://simce.cl/simce/index.php?id=228&iRBD=11261&iVRBD=5&iNivel=0&iAnio=. Retrieved 11 July 2010.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 "Región del Libertador General Bernardo O'Higgins". Education Ministry of Chile. http://www.mineduc.cl/index2.php?id_seccion=722&id_portal=7&id_contenido=4326. Retrieved 2010-07-05.

- ↑ El Rancahuaso Correspondents (2008-11-29). "Equipo Cheerleader de Pichilemu apuestan por campeonato mundial" (in Spanish). El Rancahuaso. http://www.elrancahuaso.cl/admin/render/noticia/16812. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 90.2 Pamphlet Pichilemu, Mágico & Natural, published by the Municipality of Pichilemu, in February 2010. Languages English and Spanish.

Further reading

- Arraño Acevedo, José (1999) (in Spanish). Pichilemu y Sus Alrededores Turísticos. Pichilemu, Chile: Editora El Promoucae.

- Arraño Acevedo, José (June 2003) (in Spanish). Hombres y Cosas de Pichilemu. Pichilemu, Chile.

- Boza Díaz, Cristián (1986) (in Spanish). Balnearios tradicionales de Chile: su arquitectura. Santiago, Chile: Editorial Montt Palumbo.

- Del Río Pereira, Carmen and Gutierrez Marín, Fernando (May 2002) (in Spanish). Patrimonio Arquitectónico de la Sexta Región, 4º Parte. Santiago, Chile.

- Donoso Fernández, Mariana (2000) (in Spanish). 10 Concursos Nacionales Iglesis Prat Arquitectos; Editorial FAU U. de Chile. Santiago, Chile.

- Medina, José Toribio (1908) (in Spanish). Los Restos Indígenas de Pichilemu. Santiago, Chile. — Available at Spanish Wikisource

- Mella Polanco, Juan (February 1996) (in Spanish). Historia Urbana de Pichilemu: Origen y crecimiento. Chile: Editorial Bogavantes.

- Saldías González, Antonio (1990) (in Spanish). Pichilemu, mis fuentes de información. Pichilemu, Chile: Editora El Promaucae.

External links

- Official website (Spanish)

- Official Cahuil website (English)

- News site of Pichilemu (Spanish)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||