Phrygia

| Ancient Region of Anatolia Phrygia |

|

| Location | Central Anatolia |

| State existed: | Dominant kingdom in Asia Minor from c.1200–700 BC |

| Biggest city | Gordium |

| Roman province | Galatia, Asia |

|

|

In antiquity, Phrygia (Greek: Φρυγία, η ) was a kingdom in the west central part of Anatolia, in what is now modern-day Turkey. The Phrygians (Phruges or Phryges) initially lived in the southern Balkans; according to Herodotus, under the name of Bryges (Briges), changing it to Phruges after their final migration to Anatolia, via the Hellespont.

During the flourishing of the city-state of Troy, a part of the Bryges emigrated to Anatolia as Trojan allies or under the protection of Troy. The Trojan language did not survive; consequently, its exact relationship to the Phrygian language and the affinity of Phrygian society to that of Troy remain open questions. Similarly, the date of migration and the relationship of the Phrygians to the Hittite empire are unknown. They are, however, often considered part of a "Thraco-Phrygian" group. A conventional date of c. 1200 BC often is used, at the very end of the Hittite empire. It is certain that Phrygia was constituted on Hittite land, and yet not at the very center of Hittite power in the big bend of the Halys River, where Ankara now is.

From tribal and village beginnings, the state of Phrygia arose in the 8th century BC with its capital at Gordium. During this period, the Phrygians extended eastward and encroached upon the kingdom of Urartu, the descendants of the Hurrians, a former rival of the Hittites.

Meanwhile the Phrygian Kingdom was overwhelmed by Iranian Cimmerian invaders c. 690 BC, then briefly conquered by its neighbor Lydia, before it passed successively into the Persian Empire of Cyrus and the empire of Alexander and his successors, was taken by the Attalids of Pergamon, and eventually became part of the Roman Empire. The last mentions of the language date to the 5th century AD and it was likely extinct by the 7th century AD.[1]

Contents |

Geography

Homer

Phrygians are mentioned by Homer as dwelling in two regions of Anatolia:

- In Ascania, the region around Lake Ascania in Bithynia of northwest Anatolia.[2] The Trojan allies mentioned in the Catalog of Trojans are from there.[3]

- In the "swift-horsed" country of Phrygia, a land of "many fortresses", on the banks of the Sangarius (now Sakarya River), the third longest river in modern Turkey, which flows north and west to empty into the Black Sea. There Otreus is king.[4] Priam once was there on the occasion of the war of the Phrygians against the Amazons and reports seeing many horses and that the leaders of the Phrygians were Otreus and Mygdon.[5] Priam's wife's brother, Asios, was the son of Dymas, a Phrygian.[6]

Other

Later, Phrygia was conceived as lying west of the Halys River (now Kızıl River) and east of Mysia and Lydia.

Culture

It was the "Great Mother", Cybele, as the Greeks and Romans knew her, who was originally worshiped in the mountains of Phrygia, where she was known as "Mountain Mother". In her typical Phrygian form, she wears a long belted dress, a polos (a high cylindrical headdress), and a veil covering the whole body. The later version of Cybele was established by a pupil of Phidias, the sculptor Agoracritus, and became the image most widely adopted by Cybele's expanding following, both in the Aegean world and at Rome. It shows her humanized though still enthroned, her hand resting on an attendant lion and the other holding the tympanon, a circular frame drum, similar to a tambourine.

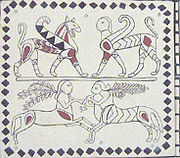

The Phrygians also venerated Sabazios, the sky and father-god depicted on horseback. Although the Greeks associated Sabazios with Zeus, representations of him, even at Roman times, show him as a horseman god. His conflicts with the indigenous Mother Goddess, whose creature was the Lunar Bull, may be surmised in the way that Sabazios' horse places a hoof on the head of a bull, in a Roman relief at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Phrygia developed an advanced Bronze Age culture. The earliest traditions of Greek music derived from Phrygia, transmitted through the Greek colonies in Anatolia, and included the Phrygian mode, which was considered to be the warlike mode in ancient Greek music. Phrygian Midas, the king of the "golden touch", was tutored in music by Orpheus himself, according to the myth. Another musical invention that came from Phrygia was the aulos, a reed instrument with two pipes. Marsyas, the satyr who first formed the instrument using the hollowed antler of a stag, was a Phrygian follower of Cybele. He unwisely competed in music with the Olympian Apollo and inevitably lost, whereupon Apollo flayed Marsyas alive and provocatively hung his skin on Cybele's own sacred tree, a pine.

Phrygia retained a separate cultural identity. Classical Greek iconography identifies the Trojan Paris as non-Greek by his Phrygian cap, which was worn by Mithras and survived into modern imagery as the "Liberty cap" of the American and French revolutionaries. The Phrygians spoke an Indo-European language. (See Phrygian language.) Although the Phrygians adopted the alphabet originated by the Phoenicians, and several dozen inscriptions in the Phrygian language have been found, they remain untranslated, and so much of what is thought to be known of Phrygia is second-hand information from Greek sources.

Mythic past

Mythic kings of Phrygia were alternately named Gordias and Midas. Some sources place Tantalus as a king in Phrygia. Tantalus is endlessly punished in Tartarus, because he killed his son Pelops and sacrificially offered him to the Olympians, a reference to the suppression of human sacrifice. In the mythic age before the Trojan war, during a time of interregnum, Gordius (or Gordias), a Phrygian farmer, became king, fulfilling an oracular prophecy. The kingless Phrygians had turned for guidance to the oracle of Sabazios ("Zeus" to the Greeks) at Telmissus, in the part of Phrygia that later became part of Galatia. They had been instructed by the oracle to acclaim as their king the first man who rode up to the god's temple in a cart. That man was Gordias (Gordios, Gordius), a farmer, who dedicated the ox-cart in question, tied to its shaft with the "Gordian Knot". Gordias refounded a capital at Gordium in west central Anatolia, situated on the old trackway through the heart of Anatolia that became Darius's Persian "Royal Road" from Pessinus to Ancyra, and not far from the River Sangarius.

Myths surrounding the first king Midas connect him with Silenus and other satyrs and with Dionysus, who granted him the famous "golden touch". In another episode, he judged a musical contest between Apollo, playing the lyre, and Pan, playing the rustic pan pipes. Midas judged in favor of Pan, and Apollo awarded him the ears of an ass.

The mythic Midas of Thrace, accompanied by a band of his people, traveled to Asia Minor to wash away the taint of his unwelcome "golden touch" in the river Pactolus. Leaving the gold in the river's sands, Midas found himself in Phrygia, where he was adopted by the childless king Gordias and taken under the protection of Cybele. Acting as the visible representative of Cybele, and under her authority, it would seem, a Phrygian king could designate his successor.

According to the Iliad, the Phrygians were Trojan allies during the Trojan War. The Phrygia of Homer's Iliad appears to be located in the area that embraced the Ascanian lake and the northern flow of the Sangarius river and so was much more limited in extent than classical Phrygia. Homer's Iliad also includes a reminiscence by the Trojan king Priam, who had in his youth come to aid the Phrygians against the Amazons (Iliad 3.189). During this episode (a generation before the Trojan War), the Phrygians were said to be led by Otreus and Mygdon. Both appear to be little more than eponyms: there was a place named Otrea on the Ascanian Lake, in the vicinity of the later Nicaea; and the Mygdones were a people of Asia Minor, who resided near Lake Dascylitis (there was also a Mygdonia in Macedonia). During the Trojan War, the Phrygians sent forces to aid Troy, led by Ascanius and Phorcys, the sons of Aretaon. Asius, son of Dymas and brother of Hecabe, is another Phrygian noble who fought before Troy. Quintus Smyrnaeus mentions another Phrygian prince, named Coroebus, son of Mygdon, who fought and died at Troy; he had sued for the hand of the Trojan princess Cassandra in marriage. King Priam's wife Hecabe is usually said to be of Phrygian birth, as a daughter of King Dymas.

The Phrygian Sibyl was the priestess presiding over the Apollonian oracle at Phrygia.

According to Herodotus (Histories 2.9), the Egyptian pharaoh Psammetichus II had two children raised in isolation in order to find the original language. The children were reported to have uttered bekos which is Phrygian for "bread", so Psammetichus admitted that the Phrygians were a nation older than the Egyptians.

Josephus claimed the Phrygians were founded by the biblical figure Togarmah, grandson of Japheth and son of Gomer: "and Thrugramma the Thrugrammeans, who, as the Greeks resolved, were named Phrygians".

History

Migration

After the collapse of the Hittite Empire at the beginning of the 12th century BC, the political vacuum in central/western Anatolia was filled by a wave of Indo-European migrants and "Sea Peoples", including the Phrygians, who established their kingdom, with a capital eventually at Gordium. It is still not known whether the Phrygians were actively involved in the collapse of the Hittite capital Hattusa, or whether they simply moved into the vacuum that followed the collapse of Hittite hegemony. The so called Handmade Knobbed Ware was found by archaeologists at sites from this period in Western Anatolia. According to Greek mythographers[7], the first Phrygian Midas had been king of the Moschi (Mushki), also known as Bryges (Brigi) in the western part of archaic Thrace.

8th to 7th centuries

Assyrian sources from the 8th century BC speak of a king Mita of the Mushki, identified with king Midas of Phrygia. An Assyrian inscription records Mita as an ally of Sargon of Assyria in 709 BC. A distinctive Phrygian pottery called Polished Ware appears in the 8th century BC. The Phrygians founded a powerful kingdom which lasted until the Lydian ascendancy (7th century BC). Under kings alternately named Gordias and Midas, the independent Phrygian kingdom of the 8th and 7th centuries BC maintained close trade contacts with her neighbours in the east and the Greeks in the west. Phrygia seems to have been able to co-exist with whichever was the dominant power in eastern Anatolia at the time.

The invasion of Anatolia in the late 8th century BC to early 7th century BC by the Cimmerians was to prove fatal to independent Phrygia. Cimmerian pressure and attacks culminated in the suicide of its last king, Midas, according to legend. Gordium fell to the Cimmerians in 696 BC and was sacked and burnt, as reported much later by Herodotus.

A series of digs have opened Gordium as one of Turkey's most revealing archeological sites. Excavations confirm a violent destruction of Gordion around 675 BC. A tomb of the Midas period, popularly identified as the "Tomb of Midas" revealed a wooden structure deeply buried under a vast tumulus, containing grave goods, a coffin, furniture, and food offerings (Archaeological Museum, Ankara). The Gordium site contains a considerable later building program, perhaps by Alyattes, the Lydian king, in the 6th century BC.

Minor Phrygian kingdoms continued to exist after the end of the Phrygian empire, and the Phrygian art and culture continued to flourish. Cimmerian people stayed in Anatolia but do not appear to have created a kingdom of their own. The Lydians repulsed the Cimmerians in the 620s, and Phrygia was subsumed into a short-lived Lydian empire. The eastern part of the former Phrygian empire fell into the hands of the Medes in 585 BC.

Croesus' Lydian Empire

Under the proverbially rich King Croesus (reigned 560–546 BC), Phrygia remained part of the Lydian empire that extended east to the Halys River. There may be an echo of strife with Lydia and perhaps a veiled reference to royal hostages, in the legend of the twice-unlucky Adrastus, the son of a King Gordias with the queen, Eurynome. He accidentally killed his brother and exiled himself to Lydia, where King Croesus welcomed him. Once again, Adrastus accidentally killed Croesus' son and then committed suicide.

Persian Empire

Lydian Croesus was conquered by Cyrus in 546 BC, and Phrygia passed under Persian dominion. After Darius became Persian Emperor in 521 BC, he remade the ancient trade route into the Persian "Royal Road" and instituted administrative reforms that included setting up satrapies. The capital of the Phrygian satrapy was established at Dascylion.

Under Persian rule, the Phrygians seem to have lost their intellectual acuity and independence. Phrygians became stereotyped among later Greeks and the Romans as passive and dull.

Alexander and the successors

Alexander the Great passed through Gordium in 333 BC, famously severing the Gordian Knot in the temple of Sabazios ("Zeus"). The legend (possibly promulgated by Alexander's publicists) was that whoever untied the knot would be master of Asia. With Gordium sited on the Persian Royal Road that led through the heart of Anatolia, the prophecy had some geographical plausibility. With Alexander, Phrygia became part of the wider Hellenistic world. After Alexander's death, his successors squabbled over Anatolian dominions.

Gauls overran the eastern part of Phrygia which became part of Galatia. The former capital of Gordium was captured and destroyed by the Gauls soon afterwards and disappeared from history. In imperial times, only a small village existed on the site, and, in 188 BC, the remnant of Phrygia came under control of Pergamon. In 133 BC, western Phrygia passed to Rome.

Rome and Byzantium

For purposes of provincial administration the Romans maintained a divided Phrygia, attaching the northeastern part to the province of Galatia and the western portion to the province of Asia. During the reforms of Diocletian, Phrygia was divided anew into two provinces: Phrygia I or Phrygia Salutaris, and Phrygia II or Pacatiana, both under the Diocese of Asia. Salutaris comprised the eastern portion of the region, with Synnada as its capital, while Pacatiana comprised the western half, with Laodicea on the Lycus as capital. The provinces survived up to the end of the 7th century, when they were replaced by the Theme system. In the Byzantine period, most of Phrygia belonged to the Anatolic theme. The area was overrun by the Turks in the aftermath of the Battle of Manzikert (1071) and never fully recovered. The Byzantines were finally evicted from there in the 13th century, but the name remained in use until the collapse of the Byzantine Empire in 1453.

See also

- Bryges

- Paleo Balkan languages

- Phrygian cap

- Phrygian language

References and notes

- ↑ Swain, Simon; Adams, J. Maxwell; Janse, Mark (2002). Bilingualism in ancient society: language contact and the written word. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. pp. 246–266. ISBN 0-19-924506-1.

- ↑ Smith, William (1878). A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: J. Murray. pp. page 230.

- ↑ Homer, Iliad, Book II, line 862.

- ↑ Homeric Hymns number 5, To Aphrodite.

- ↑ Homer, Iliad, Book III line 181.

- ↑ Homer, Iliad, Book XVI, line 712.

- ↑ JG MacQueen, The Hittites and their contemporaries in Asia Minor, 1986, p. 157.

External links

|

|||||

|

|||||

| Western Empire (395–476) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Praetorian Prefecture of Gaul |

Diocese of Gaul: Alpes Poeninae et Graiae • Belgica I • Belgica II • Germania I • Germania II • Lugdunensis I • Lugdunensis II • Lugdunensis III • Lugdunensis IV • Maxima Sequanorum Diocese of Vienne (later Septem Provinciae): Alpes Maritimae • Aquitanica I • Aquitanica II • Narbonensis I • Narbonensis II • Novempopulania • Viennensis Diocese of Spain: Baetica • Baleares • Carthaginensis • Gallaecia • Lusitania • Mauretania Tingitana • Tarraconensis Diocese of Britain: Britannia I • Britannia II • Flavia Caesariensis • Maxima Caesariensis • Valentia (369) |

||

| Praetorian Prefecture of Italy |

Diocese of Suburbicarian Italy: Apulia et Calabria • Bruttia et Lucania • Campania • Corsica • Picenum Suburbicarium • Samnium • Sardinia • Sicilia • Tuscania et Umbria • Valeria Diocese of Annonarian Italy: Alpes Cottiae • Flaminia et Picenum Annonarium • Liguria et Aemilia • Raetia I • Raetia II • Venetia et Istria Diocese of Africa†: Africa proconsularis (Zeugitana) | Byzacena • Mauretania Caesariensis • Mauretania Sitifensis • Numidia Cirtensis • Numidia Militiana • Tripolitania Diocese of Pannonia (later of Illyricum): Dalmatia • Noricum mediterraneum • Noricum ripense • Pannonia I • Pannonia II • Savia • Valeria ripensis |

||

| Eastern Empire (395–ca. 640) | |||

| Praetorian Prefecture of Illyricum |

Diocese of Dacia: Dacia Mediterranea • Dacia Ripensis • Dardania • Moesia I • Praevalitana Diocese of Macedonia: Achaea • Creta • Epirus nova| Epirus vetus | Macedonia I • Macedonia II Salutaris • Thessalia |

||

| Praetorian Prefecture of the East |

Diocese of Thrace: Europa • Haemimontus • Moesia II§ • Rhodope • Scythia§ • Thracia Diocese of Asia*: Asia • Caria§ • Hellespontus • Insulae§ • Lycaonia (370) • Lycia • Lydia • Pamphylia • Pisidia • Phrygia Pacatiana • Phrygia Salutaria Diocese of Pontus*: Armenia I* • Armenia II* • Armenia Maior* • Armenian Satrapies* • Armenia III (536) • Armenia IV (536) • Bithynia • Cappadocia I* • Cappadocia II* • Galatia I* • Galatia II Salutaris* • Helenopontus* • Honorias* • Paphlagonia* • Pontus Polemoniacus* Diocese of the East: Arabia • Cilicia I • Cilicia II • Cyprus§ • Euphratensis • Isauria • Mesopotamia • Osroene • Palaestina I • Palaestina II • Palaestina III Salutaris • Phoenice • Phoenice Libanensis • Syria I • Syria II Salutaris • Theodorias (528) Diocese of Egypt: Aegyptus I • Aegyptus II • Arcadia • Augustamnica I • Augustamnica II • Libya Superior • Libya Inferior • Thebais Superior • Thebais Inferior |

||

| Other territories | Taurica • Lazica (532/562) • Spania (552) | ||

| Notes | Provincial administration reformed by Diocletian, ca. 293. Praetorian prefectures established after the death of Constantine I. Empire permanently partitioned after 395. Exarchates of Ravenna and Africa established after 584. After massive territorial loss due to the Muslim conquests, the remaining provinces were superseded by the theme system in ca. 640–660, although they survived under the latter until the early 9th century * affected (boundaries modified/abolished/renamed) by Justinian's administrative reorganization in 534–536 † re-established after reconquest by the Eastern Empire in 534, as the separate praetorian prefecture of Africa § joined together into the Quaestura exercitus in 536 |

||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

||||||||