Phoenicia

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Phoenicia (Brit. pronounced /fɨˈnɪʃə/ U.S. pronounced /fəˈniːʃə/ [2]; Phoenician: ![]()

![]()

![]()

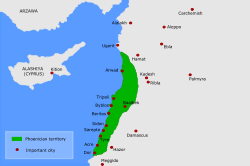

![]() , Kana`an; Hebrew: כנען: Kna`an, Greek: Φοινίκη: Phoiníkē, Latin: Phœnicia, Arabic: فينيقيا) was an ancient civilization centered in the north of ancient Canaan, with its heartland along the coastal regions of modern day Lebanon, Palestine, Syria and Israel.[3] Phoenician civilization was an enterprising maritime trading culture that spread across the Mediterranean during the period 1550 BC to 300 BC. Though ancient boundaries of such city-centered cultures fluctuated, the city of Tyre seems to have been the southernmost. Sarepta (modern day Sarafand) between Sidon and Tyre is the most thoroughly excavated city of the Phoenician homeland. The Phoenicians often traded by means of a galley, a man-powered sailing vessel, and are credited with the invention of the bireme.[4]

, Kana`an; Hebrew: כנען: Kna`an, Greek: Φοινίκη: Phoiníkē, Latin: Phœnicia, Arabic: فينيقيا) was an ancient civilization centered in the north of ancient Canaan, with its heartland along the coastal regions of modern day Lebanon, Palestine, Syria and Israel.[3] Phoenician civilization was an enterprising maritime trading culture that spread across the Mediterranean during the period 1550 BC to 300 BC. Though ancient boundaries of such city-centered cultures fluctuated, the city of Tyre seems to have been the southernmost. Sarepta (modern day Sarafand) between Sidon and Tyre is the most thoroughly excavated city of the Phoenician homeland. The Phoenicians often traded by means of a galley, a man-powered sailing vessel, and are credited with the invention of the bireme.[4]

It is uncertain to what extent the Phoenicians viewed themselves as a single ethnicity. Their civilization was organized in city-states, similar to ancient Greece. Each city-state was an independent unit politically, and they could come into conflict and one city could be dominated by another city-state, although they would collaborate in leagues or alliances.[5]

The Phoenicians were also the first state-level society to make extensive use of the alphabet. The Phoenician phonetic alphabet is generally believed to be the ancestor of almost all modern alphabets. Phoenicians spoke the Phoenician language, which belongs to the group of Canaanite languages in the Semitic language family.[6][7] Through their maritime trade, the Phoenicians spread the use of the alphabet to North Africa and Europe, where it was adopted by the Greeks, who later passed it on to the Romans and Etruscans.[8] In addition to their many inscriptions, the Phoenicians were believed to have left numerous other types of written sources, but most have not survived. Evangelical Preparation by Eusebius of Caesarea quotes extensively from Philo of Byblos and Sanchuniathon.

Contents |

History

Origins: 2300-1200 BC

|

series |

|||

| Ancient History | |||

| Phoenicia | |||

| Ancient history of Lebanon | |||

| Foreign Rule | |||

| Assyrian Rule | |||

| Babylonian Rule | |||

| Persian Rule | |||

| Macedonian Rule | |||

| Roman Rule | |||

| Byzantine Rule | |||

| Arab Era | |||

| Ottoman Rule | |||

| French Rule | |||

| Topical | |||

| Modern Lebanon | |||

| Timeline of Lebanese history | |||

In terms of archaeology, language, and religion, there is little to set the Phoenicians apart as markedly different from other cultures of Canaan. They were Canaanites. They are unique in their remarkable seafaring achievements. In the Amarna tablets of the 14th century BC, they call themselves Kenaani or Kinaani (Canaanites). Note, however, that the Amarna letters predate the invasion of the Sea Peoples by over a century. Much later in the 6th century BC, Hecataeus of Miletus writes that Phoenicia was formerly called χνα, a name Philo of Byblos later adopted into his mythology as his eponym for the Phoenicians: "Khna who was afterwards called Phoinix". Egyptian seafaring expeditions had already been made to Byblos to bring back "cedars of Lebanon" as early as the third millennium BC.

Herodotus's account (written c. 440 BC) refers to the Io and Europa myths. (History, I:1).

| “ | According to the Persians best informed in history, the Phoenicians began the quarrel. These people, who had formerly dwelt on the shores of the Erythraean Sea, modern Yemen, having migrated to the Mediterranean and settled in the parts which they now inhabit, began at once, they say, to adventure on long voyages, freighting their vessels with the wares of Egypt and Assyria… | ” |

Genetic studies

Spencer Wells of the Genographic Project has conducted genetic studies that demonstrate that male populations of Lebanon, Malta, Spain, and other areas settled by Phoenicians, share a common m89 chromosome Y type.[9] Male populations in areas associated with Minoan or with the Sea People settlement have completely different genetic markers. This implies that Minoans and Sea Peoples probably did not have ancestral relation with the Phoenicians.[2][3]

In 2004, two Harvard University educated geneticists and leading scientists of the National Geographic Genographic Project, Dr. Pierre Zalloua and Dr. Spencer Wells identified "the haplogroup of the Phoenicians" as haplogroup J2, with avenues open for future research.[10] The male populations of Tunisia and Malta were also included in this study. They were shown to share "overwhelming" genetic similarities with the Lebanese. In 2008, scientists from the Genographic Project announced that "as many as 1 in 17 men living today on the coasts of North Africa and southern Europe may have a Phoenician direct male-line ancestor." [11]

High point: 1200–800 BC

Fernand Braudel remarked in The Perspective of the World that Phoenicia was an early example of a "world-economy" surrounded by empires. The high point of Phoenician culture and seapower is usually placed ca. 1200–800 BC.

Many of the most important Phoenician settlements had been established long before this: Byblos, Tyre, Sidon, Simyra, Arwad, and Berytus, all appear in the Amarna tablets. Archeology has identified cultural elements of the Phoenician zenith as early as the third millennium BC.

The league of independent city-state ports, with others on the islands and along other coasts of the Mediterranean Sea, was ideally suited for trade between the Levant area, rich in natural resources, and the rest of the ancient world. During the early Iron Age, in around 1200 BC an unknown event occurred, historically associated with the appearance of the Sea Peoples from the north. They may have been driven south by crop failures and mass starvation following the Thera eruption. They weakened and destroyed the Egyptians and the Hittites. In the resulting power vacuum, a number of Phoenician cities rose as significant maritime powers.

The societies rested on three power-bases: the king; the temple and its priests; and councils of elders. Byblos first became the predominant center from where the Phoenicians dominated the Mediterranean and Erythraean (Red) Sea routes. It was here that the first inscription in the Phoenician alphabet was found, on the sarcophagus of Ahiram (ca. 1200 BC). Later, Tyre gained in power. One of its kings, the priest Ithobaal (887-856 BC) ruled Phoenicia as far north as Beirut, and part of Cyprus. Carthage was founded in 814 BC under Pygmalion of Tyre (820-774 BC). The collection of city-kingdoms constituting Phoenicia came to be characterized by outsiders and the Phoenicians as Sidonia or Tyria. Phoenicians and Canaanites alike were called Zidonians or Tyrians, as one Phoenician city came to prominence after another.

Decline: 539-65 BC

.jpg)

Cyrus the Great conquered Phoenicia in 539 BC. The Persians divided Phoenicia into four vassal kingdoms: Sidon, Tyre, Arwad, and Byblos. They prospered, furnishing fleets for the Persian kings. Phoenician influence declined after this. It is likely that much of the Phoenician population migrated to Carthage and other colonies following the Persian conquest. In 350 or 345 BC a rebellion in Sidon led by Tennes was crushed by Artaxerxes III. Its destruction was described by Diodorus Siculus.

Alexander the Great took Tyre in 332 BC following the Siege of Tyre. Alexander was exceptionally harsh to Tyre, executing 2000 of the leading citizens, but he maintained the king in power. He gained control of the other cities peacefully: the ruler of Aradus submitted; the king of Sidon was overthrown. The rise of Hellenistic Greece gradually ousted the remnants of Phoenicia's former dominance over the Eastern Mediterranean trade routes. Phoenician culture disappeared entirely in the motherland. Carthage continued to flourish in North Africa. It oversaw mining iron and precious metals from Iberia, and used its considerable naval power and mercenary armies to protect commercial interests. Rome finally destroyed it in 146 BC, at the end of the Punic Wars.

Following Alexander, the Phoenician homeland was controlled by a succession of Hellenistic rulers: Laomedon (323 BC), Ptolemy I (320), Antigonus II (315), Demetrius (301), and Seleucus (296). Between 286 and 197 BC, Phoenicia (except for Aradus) fell to the Ptolemies of Egypt, who installed the high priests of Astarte as vassal rulers in Sidon (Eshmunazar I, Tabnit, Eshmunazar II).

In 197 BC, Phoenicia along with Syria reverted to the Seleucids. The region became increasingly Hellenized, although Tyre became autonomous in 126 BC, followed by Sidon in 111. Syria, including Phoenicia, were seized by king Tigranes the Great from 82 until 69 BC, when he was defeated by Lucullus. In 65 BC Pompey finally incorporated the territory as part of the Roman province of Syria.

In the 21st century, genetic studies have shown many men among current Maltese people to have lines of direct descent from Phoenicians.[9]

Trade

The Phoenicians were amongst the greatest traders of their time and owed a great deal of their prosperity to trade. The Phoenicians' initial trading partners were the Greeks, with whom they used to trade wood, slaves, glass and powdered Tyrian Purple, used by the Greek elite to color clothes and other garments and not available anywhere else. Without trade with the Greeks they would not be known as Phoenicians, as the word for Phoenician is derived from the Ancient Greek word phoinikèia meaning "purple".

In the centuries following 1200 BC, the Phoenicians formed the major naval and trading power of the region. Phoenician trade was founded on Tyrian Purple, a violet-purple dye derived from the Murex sea-snail's shell, once profusely available in coastal waters of the eastern Mediterranean Sea but exploited to local extinction. James B. Pritchard's excavations at Sarepta in present day Lebanon revealed crushed Murex shells and pottery containers stained with the dye that was being produced at the site. The Phoenicians established a second production center for the purple dye in Mogador, in present day Morocco. Brilliant textiles were a part of Phoenician wealth, and Phoenician glass was another export ware. They traded unrefined, prick-eared hunting dogs of Asian or African origin which locally they had developed into many breeds such as the Basenji, Ibizan Hound, Pharaoh Hound, Cirneco dell'Etna, Cretan Hound, Canary Islands Hound and Portuguese Podengo. To Egypt, where the grapevine would not grow, the 8th-century Phoenicians sent wine: the wine trade with Egypt is vividly documented by the shipwrecks located in 1997 in the open sea thirty miles west of Ascalon;[12] pottery kilns at Tyre and Sarepta produced the big terracotta jars used for transporting wine. Egypt in turn was the outlet for Nubian gold.

From elsewhere they obtained other materials, perhaps the most important being silver from Iberian Peninsula and tin from Great Britain, the latter of which when smelted with copper (from Cyprus) created the durable metal alloy bronze. Strabo states that there was a highly lucrative Phoenician trade with Britain for tin.

The Phoenicians established commercial outposts throughout the Mediterranean, the most strategically important being Carthage in North Africa, directly across the narrow straits. Ancient Gaelic mythologies attribute a Phoenician/Scythian influx to Ireland by a leader called Fenius Farsa. Others also sailed south along the coast of Africa. A Carthaginian expedition led by Hanno the Navigator explored and colonized the Atlantic coast of Africa as far as the Gulf of Guinea; and according to Herodotus, a Phoenician expedition sent down the Red Sea by pharaoh Necho II of Egypt (c. 600 BC) even circumnavigated Africa and returned through the Pillars of Hercules in three years.

Important cities and colonies

From the 10th century BC, their expansive culture established cities and colonies throughout the Mediterranean. Canaanite deities like Baal and Astarte were being worshipped from Cyprus to Sardinia, Malta, Sicily, Spain, Portugal, and most notably at Carthage in modern Tunisia.

In the Phoenician homeland:

- Arka

- Arwad (Classical Aradus)

- Berut (Greek Βηρυτός; Latin Berytus;

Arabic بيروت; English Beirut) - Botrys (modern Batroun)

- Gebal (Greek Byblos)

- Porphyreon

- Safita

- Sarepta (modern Sarafand)

Phoenician colonies, including some of lesser importance (this list might be incomplete):

|

|

Culture

Language and literature

The Phoenician alphabet was one of the first alphabets with a strict and consistent form. It is assumed that it adopted its simplified linear characters from an as-yet unattested early pictorial Semitic alphabet developed some centuries earlier in the southern Levant.[22][23] The precursor to the Phoenician alphabet was likely of Egyptian origin as Middle Bronze Age alphabets from the southern Levant resemble Egyptian hieroglyphs, or more specifically an early alphabetic writing system found at Wadi-el-Hol in central Egypt.[24][25] In addition to being preceded by proto-Canaanite, the Phoenician alphabet was also preceded by an alphabetic script of Mesopotamian origin called Ugaritic. The development of the Phoenician alphabet from the Proto-Canaanite coincided with the rise of the Iron Age in the 11th century BCE.[26]

This alphabet has been termed an abjad or a script that contains no vowels. The first two letters aleph and beth gave the name to the alphabet.

The oldest known representation of the Phoenician alphabet is inscribed on the sarcophagus of King Ahiram of Byblos, dating to the 11th century BCE at the latest. Phoenician inscriptions are found in Lebanon, Syria, Israel, Cyprus and other locations, as late as the early centuries of the Christian Era. The Phoenicians are credited with spreading the Phoenician alphabet throughout the Mediterranean world.[27] Phoenician traders disseminated this writing system along Aegean trade routes, to Creta and Greece. The Greeks adopted the majority of these letters but changed some of them to vowels which were significable in their language, giving rise to the first true alphabet.

The Phoenician language is classified in the Canaanite subgroup of Northwest Semitic. Its later descendant in North Africa is termed Punic. In Phoenician colonies around the western Mediterranean, beginning in the 9th century BC, Phoenician evolved into Punic. Punic Phoenician was still spoken in the 5th century CE: St. Augustine, for example, grew up in North Africa and was familiar with the language.

Art

Phoenician art had no unique characteristic that could be identified with. This is due to the fact that Phoenicians were influenced by foreign designs and artistic cultures mainly from Egypt, Greece and Assyria. Phoenicians who were taught on the banks of the Nile and the Euphrates gained a wide artistic experience and finally came to create their own art, which was an amalgam of foreign models and perspectives.[28] In an article from The New York Times published on January 5, 1879, Phoenician art was described by the following:

He entered into other men's labors and made most of his heritage. The Sphinx of Egypt became Asiatic, and its new form was transplanted to Nineveh on the one side and to Greece on the other. The rosettes and other patterns of the Babylonian cylinders were introduced into the handiwork of Phoenicia, and so passed on to the West, while the hero of the ancient Chaldean epic became first the Tyrian Melkarth, and then the Herakles of Hellas.

Gods

Attested 2nd Millennium

Gebory-Kon |

Attested 1st Millennium

|

Influence in the Mediterranean region

Phoenician culture had a huge effect upon the cultures of the Mediterranean basin in the early Iron Age, and had also been affected in reverse. For example, in Phoenicia, the tripartite division between Baal, Mot and Yam seems to have been influenced by the Greek division between Zeus, Hades and Poseidon. Phoenician temples in various Mediterranean ports sacred to Phoenician Melkart, during the classical period, were recognized as sacred to Hercules. Stories like the Rape of Europa, and the coming of Cadmus also draw upon Phoenician influence.

The recovery of the Mediterranean economy after the late Bronze Age collapse, seems to have been largely due to the work of Phoenician traders and merchant princes, who re-established long distance trade between Egypt and Mesopotamia in the 10th century BC. The Ionian revolution was, at least in legend, led by philosophers such as Thales of Miletus or Pythagoras, both of whom had Phoenician fathers. Phoenician motifs are also present in the Orientalising period of Greek art, and Phoenicians also played a formative role in Etruscan civilisation in Tuscany.

There are many countries and cities around the world that derive their names from the Phoenician Language. Below is a list with the respective meanings:

- Altiburus: City in Algeria, SW of Carthage. From Phoenician: "Iltabrush"

- Bosa: City in Sardinia: From Phoenician "Bis'en"

- Cádiz: City in Spain: From Phoenician "Gadir"

- Dhali (Idalion): City in Central Cyprus: From Phoenician "Idyal"

- Erice: City in Sicily: From Phoenician "Eryx"

- Malta: Island in the Mediterranean: From Phoenician "Malat" ('refuge')

- Marion: City in West Cyprus: From Phoenician "Aymar"

- Oed Dekri: City in Algeria: From Phoenician: "Idiqra"

- Spain: From Phoenician: "I-Shaphan", meaning "Land of Hyraxes". Later Latinized as "Hispania"

In the Bible

Hiram (also spelled Huran) associated with the building of the temple.

| “ | 2 Chronicles 2:14—The son of a woman of the daughters of Dan, and his father [was] a man of Tyre, skillful to work in gold, silver, brass, iron, stone, timber, royal purple(from the Murex), blue, and in crimson, and fine linens; also to grave any manner of graving, and to find out every device which shall be put to him… | ” |

This is the architect of the Temple, Hiram Abiff of Masonic lore. They are vastly famous for their purple dye.

Later, reforming prophets railed against the practice of drawing royal wives from among foreigners: Elijah execrated Jezebel, the princess from Tyre who became a consort of King Ahab and introduced the worship of her gods Baal.

Long after Phoenician culture had flourished, or Phoenicia had existed as any political entity, Hellenized natives of the region where Canaanites still lived were referred to as "Syro-Phoenician", as in the Gospel of Mark 7:26: "The woman was a Greek, a Syrophoenician by birth…"

The word Bible itself ultimately derives through Greek from the word "biblion" which means "book", and not from the Hellenised Phoenician city of Byblos (which was called Gebal), before it was named by the Greeks as Byblos. The Greeks called it Byblos because it was through Gebal that bublos (Bύβλος ["Egyptian papyrus"]) was imported into Greece. Present day Byblos is under the current Arabic name of Jbeil (جبيل Ǧubayl) derived from Gebal.

Etymology

The name Phoenician, through Latin poenicus (later punicus), comes from Greek phoinikes, attested since Homer and influenced by phoînix "Tyrian purple, crimson; murex" (itself from phoinos "blood red")[29]. The word stems from Linear B po-ni-ki-jo, ultimately borrowed from Ancient Egyptian Fenkhu (Fnkhw)[30] "Syrian people". The association of phoinikes with phoînix mirrors an older folk etymology present in Phoenician which tied Kina'ahu "Canaan; Phoenicia" with kinahu "crimson".[31] The land was natively known as Kina'ahu, reported in the 6th century BC by Hecataeus under the Greek-influenced form Khna (χνα), and its people as the Kena'ani.

Hippoi

The Greeks had two names for Phoenician ships: hippoi and galloi. Galloi means tubs and hippoi means horses. These names are readily explained by depictions of Phoenician ships in the palaces of Assyrian kings from the 7th and 8th centuries, as the ships in these images are tub shaped (galloi) and have horse heads on the ends of them (hippoi). It is possible that these hippoi come from Phoenician connections with the Greek god Poseidon.

Depictions

The Tel Balawat gates (850 BC) are found in the palace of Shalmaneser, an Assyrian king, near Nimrud. They are made of bronze, and they portray ships coming to honor Shalmaneser.[32][33] The Khorsabad bas-relief (7th Century BC) shows the transportation of timber (most likely cedar) from Lebanon. It is found in the palace built specifically for Sargon II, another Assyrian king, at Khorsabad, now northern Iraq.[34][35]

Relationship between the Greeks and Phoenicians

Trade

In the Late Bronze Age (around 1200 BC) there was trade between the Canaanites (early Phoenicians), Egypt, Cyprus, and Greece. In a shipwreck found off of the coast of Turkey, the Ulu Bulurun wreck, Canaanite storage pottery along with pottery from Cyprus and Greece was found. The Phoenicians were famous metalworkers, and by the end of the 8th Century BC, Greek city-states were sending out envoys to the Levant (the eastern Mediterranean) for metal goods.[36]

The height of Phoenician trade was around the 7th and 8th centuries. There is a dispersal of imports (ceramic, stone, and faience) from the Levant that traces a Phoenician commercial channel to the Greek mainland via the central Aegean.[36] Athens shows little evidence of this trade with few eastern imports, but other Greek costal cities are rich with eastern imports that evidence this trade.[37]

Al Mina is a specific example of the trade that took place between the Greeks and the Phoenicians.[38] It has been theorized that by the 8th century BC, Euboean traders established a commercial enterprise with the Levantine coast and were using Al Mina (in Syria) as a base for this enterprise. There is still some question about the veracity of these claims concerning Al Mina.[39] The Phoenicians even got their name from the Greeks due to their trade. Their most famous trading product was purple dye, the Greek word for which is phoenos.[40]

Alphabet

The Phoenician phonetic alphabet was adopted and modified by the Greeks probably at the 8th century BC (around the time of the hippoi depictions). This most likely did not come from a single instance but from a culmination of commercial exchange.[40] This means that before the 8th century, there was a relationship between the Greeks and the Phoenicians. It would be very possible in this time that there was also an adoptation of some religious ideas as well. Herodotus cited the city of Thebes (a city in central Greece) as the place of the importation of the alphabet. The famous Phoenician Kadmos is credited with bringing the alphabet to Greece, but it is more possible that it was brought by Phoenecian emmigrants in Creta.[41]

Connections between Greek and Phoenician religions/mythology

Kadmos

In both Phoenician and Greek mythologies, Kadmos is a Phoenician prince, the son of Agenor, the king of Tyre. Herodotus credits Kadmos for bringing the Phoenician alphabet to Greece[42]. "So these Phoenicians, including the Gephyraians, came with Kadmos and settled this land, and they transmitted much lore to the Hellenes, and in particular, taught them the alphabet which, I believe the Hellenes did not have previously, but which was originally used by all Phoenicians" - The Landmark Herodotus: The Histories, Book 5.58, translated by Andrea L. Purvis

Phoenician gods of the sea

Due to the number of deities similar to the “Lord of the Sea” in classical mythology, there have been many difficulties attributing one specific name to the sea deity or the “Poseidon–Neptune” figure of Phoenician religion. This figure of “Poseidon-Neptune” is mentioned by authors and in various inscriptions as being very important to merchants and sailors [43], but a singular name has yet to be found. There are, however, names for sea gods from individual city-states. Ugarit is an ancient city state of Phoencia. Yamm is the Ugaritic god of the sea. Yamm and Baal, the storm god of Ugaritic myth and often associated with Zeus, have an epic battle for power over the universe. While Yamm is the god of the sea, he truly represents vast chaos [44]. Baal, on the other hand, is a representative for order. In Ugaritic myth, Baal overcomes Yamm's power. In some versions of this myth, Baal kills Yamm with a mace fashioned for him, and in others, the goddess Athtart saves Yamm and says that since defeated, he should stay in his own province. Yamm is the brother of the god of death, Mot.[45]

Poseidon

The trident bearing sire of swelling Ocean – Ovid, Metamorphoses, pg 256, translated by Rolfe Humphries

Poseidon is the god of the sea, earthquakes, and horses in ancient Greece. Horses, tridents and fish often represent him. He is the brother of Zeus and Hades, and his consort was Amphitrite.[46]

Overlap between the two

In antiquity, the two forces represented by Poseidon, horses and the sea, were chaotic forces that the Greeks had to tame to control and order their world. Yamm was also a chaotic force that had to be tamed. Once Yamm was under Baal’s control, the universe could assume its proper order, just as the universe assumed its proper order after Zeus was declared supreme ruler, and Poseidon was placed under him. Zeus and Poseidon were in a constant power struggle, as Poseidon worked to achieve his own ends under the rule of his brother. Though they were not brothers, Baal and Yamm were also in conflict against one another. While the reason for this possible Phoenician adaptation of Poseidon, as shown in the hippoi, is unknown it could be postulated that it may have had something to do with the Phoenicians' expanding worldview. Yamm seems to be less civilized, and more malicious than Poseidon. For example, Poseidon’s attempts to gain power are never to the point of killing Zeus, while Yamm tried to do just that to Baal. Perhaps as the Phoenicians grew more cultured and technologically advanced and as their experiences with the outside world (specifically the Greeks) grew, their need for a chaos figure progressed from ultimate chaos (Yamm) in the universe to a more earthly and controllable one, like the one Poseidon represents.

In light of both the religious connections and the interaction between Greece and Phoenicia at the time of the hippoi depictions, it is not hard to imagine that perhaps the hippoi on the ends of the ships were indeed a product of Greek religious influence on the Phoenicians. It would be logical that these horse heads would be on Phoenician ships, as they were great seafarers and Poseidon was the God of the sea. With his protection, the Phoenicians would be able to carry out their duties on the sea.

See also

- Phoenicianism

- Punic

- Carthage

- Names of the Levant

- Tarut Island

References

- ↑ "Phoenicia". The Encyclopedia of World History, Sixth edition. Houghton Mifflin Company. 2001. pp. 1. http://www.bartleby.com/67/109.html. Retrieved 2008-12-11.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary

- ↑ Sabatino Moscati. The Phoenicians. p23.

- ↑ Casson, Lionel (December 1, 1995). Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World. The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-0801851308. http://books.google.com/?id=sDpMh0gK2OUC&pg=PA3&dq=+bireme+Assyrian+Casson.

- ↑ María Eugenia Aubet. The Phoenicians and the West: politics, colonies and trade. p17. Cambridge University Press 2001

- ↑ Glenn Markoe.Phoenicians. p108. University of California Press 2000

- ↑ Zellig Sabbettai Harris. A grammar of the Phoenician language. p6. 1990

- ↑ Edward Clodd, Story of the Alphabet (Kessinger) 2003:192ff

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "In the Wake of the Phoenicians: DNA study reveals a Phoenician-Maltese link". National Geographic. 8 January 2008. http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/ngm/0410/feature2/online_extra.html.

- ↑ Phoenicians - "One-third of Maltese found to have ancient Phoenician DNA", National Geographic Magazine, October 2004 - The Malta Independent Online. Accessed on March 10, 2008

- ↑ "Phoenicians Left Deep Genetic Mark, Study Shows". The New York Times. 2008-10-31. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/31/science/31genes.html?ex=1383105600&en=f652918f500a3725&ei=5124&partner=digg&exprod=digg. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ↑ L.E. Stager, "Phoenician shipwrecks in the deep sea", in From Sidon to Huelva: Searoutes: Interconnections in the Mediterranean, 16th—6th c. BC 2003:233-48.

- ↑ Claudian, B. Gild. 518

- ↑ http://www.edrichton.com/MdinaHistory.htm History of Mdina

- ↑ J.G. Baldacchino & T.J. Dunbabin, “Rock tomb at Għajn Qajjet, near Rabat, Malta”, Papers of the British School at Rome, 21 (1953) 32-41.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 http://members.ziggo.nl/bezver/romans.html A History of Malta

- ↑ Annual Report on the Working of the Museum Department 1926-27, Malta 1927, 8; W. Culican, “The repertoire of Phoenician pottery”, Phönizier im Westen, Mainz 1982, 45-82.

- ↑ Annual Report on the Working of the Museum Department 1916-7, Malta 1917, 9-10.

- ↑ C. Michael Hogan, Mogador: promontory fort, The Megalithic Portal, ed. A. Burnham, Nov. 2, 2007 [1]

- ↑ Luís Fraga da Silva (2008), THE ROMAN TOWN OF BALSA - An encyclopedic entry, Associação Campo Arqueológico de Tavira, Tavira, Portugal.

- ↑ Luís Fraga da Silva (2008), Povoado Fenício de Tavira (VII a VI a.C.) - Reconstituição conjectural, Associação Campo Arqueológico de Tavira, Tavira, Portugal. (in Portuguese).

- ↑ Coulmas, Florian (1996). The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Writing Systems. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.. ISBN 0-631-21481-X.

- ↑ Millard 1986, p. 396

- ↑ http://www.ancientscripts.com/protosinaitic.html

- ↑ The New York Times. 1999-11-13. http://www.nytimes.com/library/national/science/111499sci-alphabet-origin.html. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ↑ http://www.omniglot.com/writing/phoenician.htm

- ↑ Beck, Roger B.; Linda Black, Larry S. Krieger, Phillip C. Naylor, Dahia Ibo Shabaka, (1999). World History: Patterns of Interaction. Evanston, IL: McDougal Littell. ISBN 0-395-87274-X.

- ↑ "Phoenician Art" (.pdf). The New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?_r=1&res=9800E4DF123EE73BBC4D53DFB7668382669FDE&oref=slogin. Retrieved 2008-06-20.

- ↑ Gove, Philip Babcock, ed. Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the English Language Unabridged. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster, 1993.

- ↑ Françoise Briquel-Chatonnet and Eric Gubel, Les Phéniciens : Aux origines du Liban (Paris: Gallimard, 1999), 18.

- ↑ Mireille Hadas-Lebel, Entre la Bible et l'Histoire : Le Peuple hébreu (Paris: Gallimard, 1997), 14.

- ↑ Markoe, G. E. 2000. Peoples of the Past: Phoenicians. Los Angeles: University of California Press

- ↑ http://www.qsov.com/UK2006/718BM.JPG

- ↑ Assyria: Khorsabad (Room10c). http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/galleries/middle_east/room_10c_assyria_khorsabad.aspx. (2 May 2009)

- ↑ http://wpcontent.answers.com/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6f/Transport_of_cedar_Dur_Sharrukin.jpg/180px-Transport_of_cedar_Dur_Sharrukin.jpg

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 1999. Canaan and Ancient Israel. http://www.museum.upenn.edu/Canaan/index.html

- ↑ Markoe, G. E. 2000. Peoples of the Past: Phoenicians. Los Angeles: University of California Press p. 174

- ↑ Boardman, J. 1964. The Greeks Overseas. London: Thames and Hudson Limited

- ↑ Markoe, G. E. 2000. Peoples of the Past: Phoenicians. Los Angeles: University of California Press p.174

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Moscati, S. 1965. The World of the Phoenicians. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, Inc., Publishers

- ↑ L.H.Jeffery.(1976).The archaic Greece.The Greek city states 700-500 BC.Ernest Benn Ltd&Tonnbridge.

- ↑ Markoe, G. E. 2000. Peoples of the Past: Phoenicians. Los Angeles: University of California Press p.112

- ↑ Ribichini, S. 1988. " Beliefs and Religious Life." In The Phoenicians, edited by Sabatino Moscati, 104-125. Milan: Gruppo Editoriale Fabbri.

- ↑ Habel, N.C. 1964. Yahweh Versus Baal: A Conflict of Religious Cultures. New York: Bookman Associates

- ↑ Ringgren, H. 1917. Religions of the Ancient Near East. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press

- ↑ Mikalson, J.D. 2005. Ancient Greek Religion. Malden: Blackwell publishing

- Assyria: Khorsabad (Room10c). http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/galleries/middle_east/room_10c_assyria_khorsabad.aspx. (2 May 2009

- Boardman, J. 1964. The Greeks Overseas. London: Thames and Hudson Limited

- Bondi, S. F. 1988. "The Course of History." In The Phoenicians, edited by Sabatino Moscati, 38-45. Milan: Gruppo Editoriale Fabbri.

- Gordon, C. H. 1966. Ugarit and Minoan Crete. New York: W.W. Norton & Company

- Habel, N.C. 1964. Yahweh Versus Baal: A Conflict of Religious Cultures. New York: Bookman Associates

- Heard, C. Yahwism and Baalism in Israel & Judah (3 May 2009).

- Herodotus. 440 BC. The Histories. Translated by Andrea L. Purvis. New York: Pantheon Books

- Homer. 6th century BC (perhaps 700 BC). The Odyssey. Translated by Stanley Lombardo. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company.

- Markoe, G. E. 2000. Peoples of the Past: Phoenicians. Los Angeles: University of California Press

- Mikalson, J.D. 2005. Ancient Greek Religion. Malden: Blackwell publishing

- Moscati, S. 1965. The World of the Phoenicians. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, Inc., Publishers

- Ovid. 1st Cent AD. Metamorphoses. Translated by Rolfe Humphries. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Ribichini, S. 1988. "Beliefs and Religious Life." In The Phoenicians, edited by Sabatino Moscati, 104-125. Milan: Gruppo Editoriale Fabbri.

- Ringgren, H. 1917. Religions of the Ancient Near East. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press

- 1999. Canaan and Ancient Israel. http://www.museum.upenn.edu/Canaan/index.html

Bibliography

- Aubet, Maria Eugenia, The Phoenicians and the West: Politics, Colonies and Trade, tr. Mary Turton (Bryn Mawr Classical Review, 2001: review)

- The History of Phoenicia, first published in 1889 by George Rawlinson is available under Project Gutenberg at: http://digital.library.upenn.edu/webbin/gutbook/lookup?num=2331 Rawlinson's 19th century text needs updating for modern improvements in historical understanding.

- Todd, Malcolm; Andrew Fleming (1987). The South West to AD 1,000 (Regional history of England series No.:8). Harlow, Essex: Longman. ISBN 0-582-49274-2 (Paperback), 0-582-49273-4 (hardback)., for a critical examination of the evidence of Phoenician trade with the South West of the U.K.

- Markoe, Glenn (2000). Phoenicians. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-226135 (hardback).

- Thiollet, Jean-Pierre, Je m'appelle Byblos, H & D, Paris, 2005. ISBN 2 914 266 04 9

External links

- Information on Canaan and Phoenicians

- The quest for the Phoenicians in South Lebanon

- The Phoenician Ship Expedition

- Phoenicia at the Ancient History Encyclopedia: Timeline, Illustrations, Articles, Books

- DNA legacy of ancient seafarers

|

|||||||