Phencyclidine

Phencyclidine (a complex clip of the chemical name 1-(1-phenylcyclohexyl)piperidine, commonly initialized as PCP), also known as angel dust and other street names, is a recreational, dissociative drug formerly used as an anesthetic agent, exhibiting hallucinogenic and neurotoxic effects.[1] Developed in 1926,[2] it was first patented in 1952 by the Parke-Davis pharmaceutical company and marketed under the brand name Sernyl. In chemical structure, PCP is an arylcyclohexylamine derivative, and, in pharmacology, it is a member of the family of dissociative anesthetics. PCP works primarily as an NMDA receptor antagonist, which blocks the activity of the NMDA receptor and, like most antiglutamatergic hallucinogens, is significantly more dangerous than other categories of hallucinogens.[3][4] Other NMDA receptor antagonists include ketamine, tiletamine, and dextromethorphan. Although the primary psychoactive effects of the drug lasts for a few hours, the total elimination rate from the body typically extends eight days or longer.

Biochemistry and pharmacology

Biochemical action

In a similar manner, PCP and analogues also inhibit nicotinic acetylcholine receptor channels (nAChR). Some analogues have greater potency at nAChR than at NMDAR. In some brain regions, these effects act synergistically to inhibit excitatory activity. wPCP (and ketamine) also act as potent D2 receptor partial agonists,[5] as well as dopamine reuptake inhibitors.

PCP is retained in fatty tissue and is broken down by the human metabolism into PCHP, PPC and PCAA.

The most troubling clinical effects are most likely produced by the action of phencyclidine on the D2 receptor. This has been suggested to account for most of the psychotic features.[6] The relative immunity to pain is likely produced by indirect interaction with the endogenous endorphin and enkephalin system that has been found in rats.[7]

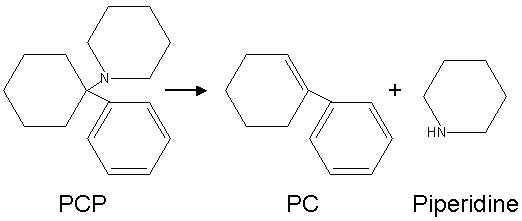

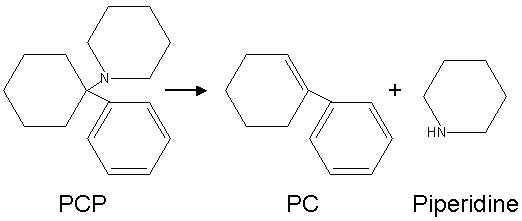

When smoked, some of it is broken down by heat into 1-phenyl-1-cyclohexene (PC) and piperidine.

Structural analogs

Possible Analogues of PCP

More than 30 different analogues of PCP were reported as being used on the street during the 1970s and 1980s, mainly in the USA. The best known of these are PCPy (rolicyclidine, 1-(1-phenylcyclohexyl)pyrrolidine); PCE (eticyclidine, N-ethyl-1-phenylcyclohexylamine); and TCP (tenocyclidine, 1-(1-(2-Thienyl)cyclohexyl)piperidine). These compounds were never widely-used and did not seem to be as well-accepted by users as PCP itself, however they were all added onto Schedule I of the Controlled Substance Act because of their putative similar effects.[8]

The generalized structural motif required for PCP-like activity is derived from structure-activity relationship studies of PCP analogues, and summarized below. All of these analogues would have somewhat similar effects to PCP itself, although, with a range of potencies and varying mixtures of anesthetic, dissociative and stimulant effects depending on the particular substituents used. In some countries such as the USA, Australia, and New Zealand, all of these compounds would be considered controlled substance analogues of PCP, and are hence illegal drugs, even though many of them have never been made or tested.[9][10]

Brain effects

Like other NMDA receptor antagonists, it is postulated that phencyclidine can cause a certain kind of brain damage called Olney's lesions.[11][12] Studies conducted on rats showed that high doses of the NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801 caused irreversible vacuoles to form in certain regions of the rats' brains. All studies of Olney's Lesions have only been performed on animals and may not apply to humans. The research into the relationship between rat brain metabolism and the creation of Olney's Lesions has been discredited and may not apply to humans, as has been shown with ketamine.[13][14]

Phencyclidine has also been shown to cause schizophrenia-like changes in the rat brain, which are detectable both in living rats and upon necropsy examination of brain tissue.[15] It also induces symptoms in humans that are virtually indistinguishable from schizophrenia.[16]

The full extent of the pharmacology of this compound in the human CNS is not fully understood; it binds to many different receptor sites. The primary interactions are as a non-competitive antagonist at the 3A-subunit [epsilon subunit] of the NMDAR in Homo sapiens'. Phencyclidine is known to bind, with relatively high affinity, to the D1 subunit of the human DAT (Dopamine Transporter), in addition to displaying a positive antagonistic effect at the α7-subunit of the Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor (nAChR). It also binds to the mu-opioid receptor, which seems to be a central part of the mechanism of action of drugs in this class. (For example, Dizocilpine [MK-801] shows little appreciable analgesic effect despite having a high specificity for the NMDA-3A and NMDA-3B subunits - this may well be mediated by the lack of related efficacy at the mu-opioid receptor, though the NMDAR certainly does play a role in transmission of pain signals).

History and medicinal use

PCP was first synthesized in 1926, and later tested after World War II as a surgical anesthetic. Because of its adverse side effects, such as hallucinations, mania, delirium, and disorientation, it was shelved until the 1950s. In 1953, it was patented by Parke-Davis and named Sernyl (referring to serenity), but was withdrawn from the market two years later because of side-effects. In 1967, it was given the trade name Sernylan and marketed as a veterinary anesthetic, but was again discontinued. Its side effects and long half-life in the human body made it unsuitable for medical applications.

Recreational use

Illicit PCP seized by the DEA in several forms.

PCP began to emerge as a recreational drug in major cities in the United States in 1967.[17] In 1978, People magazine and Mike Wallace of 60 Minutes called PCP the country's "number one" drug problem. Although recreational use of the drug had always been relatively low, it began declining significantly in the 1980s. In surveys, the amount of high school students admitting to trying PCP at least once fell from 13% in 1979 to less than 3% in 1990.[18]

PCP comes in both powder and liquid forms (PCP base is dissolved most often in ether), but typically it is sprayed onto leafy material such as cannabis, mint, oregano, parsley, or ginger leaves, then smoked.

PCP is a Schedule II substance in the United States, a List I drug of the Opium Law in the Netherlands and a Class A substance in the United Kingdom.

Method of absorption

The term "embalming fluid" is often used to refer to the liquid PCP in which a cigarette is dipped, to be ingested through smoking, commonly known as "boat" or "water." The name most likely originated from PCP's somatic "numbing" effect and the feeling of physical dissociation from the body, and has led to the widespread (mistaken) belief that the liquid is made up of or contains real embalming fluid. Occasionally, however, some users and dealers have, believing this myth, used real embalming fluid mixed with (or in place of) PCP.[19][20] Smoking PCP is known as "getting wet", and a tobacco or cannabis cigarette dipped in PCP may be referred to on the street as a "fry stick," "sherm," "amp," "toe tag", "dippa", "happy stick," or "wet stick." "Getting wet" is an increasingly popular method of using PCP, especially in the western United States where it is sold for about $10 to $25 per cigarette.

In its pure (base) form, PCP is a yellow oil (usually dissolved in petroleum or diethyl ether or tetrahydrofuran). Upon treatment with hydrogen chloride gas, or isopropyl alcohol saturated with HCl, this oil precipitates into white-tan crystals or powder (PCP hydrochloride) In this form, PCP can be insufflated, depending upon the purity. However, most PCP on the illicit market contains a number of contaminants as a result of makeshift manufacturing, causing the color to range from tan to brown, and the consistency to range from powder to a gummy mass. These contaminants can range from unreacted piperidine and other precursors, to carcinogens like benzene and cyanide-like compounds such as PCC (piperidinocyclohexyl carbonitrile).

Effects

Behavioral effects can vary by dosage. Small doses produce a numbness in the extremities and intoxication, characterized by staggering, unsteady gait, slurred speech, bloodshot eyes, and loss of balance. Moderate doses (5–10 mg intranasal, or 0.01-0.02 mg/kg intramuscular or intravenous) will produce analgesia and anesthesia. High doses may lead to convulsions.[21]

Psychological effects include severe changes in body image, loss of ego boundaries, paranoia and depersonalization. Hallucinations, euphoria, suicidal impulses and aggressive behavior are reported infrequently.[21][22] The drug has been known to alter mood states in an unpredictable fashion, causing some individuals to become detached, and others to become animated. Intoxicated individuals may act in an unpredictable fashion, possibly driven by their delusions and hallucinations. Occasionally, this leads to bizarre acts of violence.[23] However, studies by the Drug Abuse Warning Network in the 1970s show that media reports of PCP-induced violence are greatly exaggerated and that incidents of violence were unusual and often (but not always) limited to individuals with reputations for aggression regardless of drug use.[24]

Included in the portfolio of behavioral disturbances are acts of self-injury including suicide, and attacks on others or destruction of property. The analgesic properties of the drug can cause users to feel less pain, and persist in violent or injurious acts as a result. Recreational doses of the drug can also induce a psychotic state that resembles schizophrenic episodes which can last for months at a time with toxic doses. Users generally report an "out-of-body" experience where they feel detached from reality, or one's consciousness seems somewhat disconnected from consensus reality.

Symptoms are summarized by the mnemonic device RED DANES: rage, erythema (redness of skin), dilated pupils, delusions, amnesia, nystagmus (oscillation of the eyeball when moving laterally), excitation, and skin dryness.[25]

Management of intoxication

Management of phencyclidine intoxication mostly consists of supportive care — controlling breathing, circulation, and body temperature — and, in the early stages, treating psychiatric symptoms.[26][27][28] Benzodiazepines, such as lorazepam, are the drugs of choice to control agitation and seizures (when present). Typical antipsychotics such as phenothiazines and haloperidol have been used to control psychotic symptoms, but may produce many undesirable side effects — such as dystonia — and their use is therefore no longer preferred; phenothiazines are particularly risky, as they may lower the seizure threshold, worsen hyperthermia, and boost the anticholinergic effects of PCP.[26][27] If an antipsychotic is given, intramuscular haloperidol has been recommended.[28][29][30]

Forced acid diuresis (with ammonium chloride or, more safely, ascorbic acid) may increase clearance of PCP from the body, and was somewhat controversially recommended in the past as a decontamination measure.[26][27][28] However, it is now known that only around 10% of a dose of PCP is removed by the kidneys, which would make increased urinary clearance of little consequence; furthermore, urinary acidification is dangerous, as it may induce acidosis and worsen rhabdomyolysis (muscle breakdown), which is not an unusual manifestation of PCP toxicity.[26][27]

See also

References

- Inciardi, James A. (1992). The War on Drugs II. Mayfield Publishing Company. ISBN 1-55934-016-9.

- ↑ Maisto, Stephen A.; Mark Galizio, Gerard Joseph Connors (2004). Drug Use and Abuse. Thompson Wadsworth. ISBN 0155085174.

- ↑ Development of PCP

- ↑ Drugs and Behavior, 4th Edition, McKim, William A., ISBN 0-13-083146-8

- ↑ Kapur, S. and P. Seeman. "[http://www.nature.com/mp/journal/v7/n8/full/4001093a.html NMDA receptor antagonists ketamine and PCP have direct effects on while on PCP be aware of flying dicks.the dopamine D2 –844 (2002)

- ↑ Seeman P, Guan HC, Hirbec H (August 2009). "Dopamine D2High receptors stimulated by phencyclidines, lysergic acid diethylamide, salvinorin A, and modafinil". Synapse (New York, N.Y.) 63 (8): 698–704. doi:10.1002/syn.20647. PMID 19391150.

- ↑ Giannini AJ, Nageotte C, Loiselle RH, Malone DA, Price WA (1984). "Comparison of chlorpromazine, haloperidol and pimozide in the treatment of phencyclidine psychosis: DA-2 receptor specificity". Journal of Toxicology. Clinical Toxicology 22 (6): 573–9. doi:10.3109/15563658408992586. PMID 6535849.

- ↑ Castellani S, Giannini AJ, Adams PM (1982). "Effects of naloxone, metenkephalin, and morphine on phencyclidine-induced behavior in the rat". Psychopharmacology 78 (1): 76–80. doi:10.1007/BF00470593. PMID 6815700.

- ↑ PCP synthesis and effects: table of contents

- ↑ Itzhak Y, Kalir A, Weissman BA, Cohen S. New analgesic drugs derived from phencyclidine. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 1981; 24(5):496–499

- ↑ Chaudieu I, Vignon J, Chicheportiche M, Kamenka JM, Trouiller G, Chicheportiche R. Role of the aromatic group in the inhibition of phencyclidine binding and dopamine uptake by PCP analogs. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behaviour. 1989 Mar;32(3):699–705.

- ↑ Olney J, Labruyere J, Price M (1989). "Pathological changes induced in cerebrocortical neurons by phencyclidine and related drugs". Science 244 (4910): 1360–2. doi:10.1126/science.2660263. PMID 2660263.

- ↑ Hargreaves R, Hill R, Iversen L (1994). "Neuroprotective NMDA antagonists: the controversy over their potential for adverse effects on cortical neuronal morphology". Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien) 60: 15–9. PMID 7976530.

- ↑ Jansen, Karl. Ketamine: Dreams and Realities. MAPS, 2004. ISBN 0966001974

- ↑ Erowid DXM Vault : Response to "The Bad News Isn't In": Please Pass The Crow, by William E. White

- ↑ Reynolds, Lindsay M.; Susan M. Cochran, Brian J. Morris, Judith A. Pratt and Gavin P. Reynolds (March 1, 2005). "Chronic phencyclidine administration induces schizophrenia-like changes in N-acetylaspartate and N-acetylaspartylglutamate in rat brain". Schizophrenia Research 73 (2-3): 147–152. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2004.02.003. PMID 15653257.

- ↑ Murray JB (May 2002). "Phencyclidine (PCP): a dangerous drug, but useful in schizophrenia research". J Psychol 136 (3): 319–27. PMID 12206280.

- ↑ Inciardi 1992, p. 46.

- ↑ Inciardi 1992, pp. 46-49.

- ↑ http://abcnews.go.com/US/story?id=92771&page=1 Kids Use Embalming Fluid as Drug

- ↑ http://www.syracuse.com/news/index.ssf/2009/08/_syracuse_ny_the.html Illegal drug users dip into embalming fluid By Douglass Dowty / The Post-Standard August 03, 2009

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Diaz, Jaime. How Drugs Influence Behavior. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1996.

- ↑ Inciardi 1992, p. 48-49.

- ↑ http://www.straightdope.com/columns/read/2589/does-pcp-turn-people-into-cannibals Does PCP turn people into cannibals? The Straight Dope, 2005

- ↑ Inciardi 1992, p. 48.

- ↑ AJ Giannini. Drugs of Abuse--Second Edition. Los Angeles, Practice Management Information Corp.,1997,pg. 126. ISBN 1-57066-053-0.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 Helman RS, Habal R (October 6, 2008). "Phencyclidine Toxicity". eMedicine. http://www.emedicine.com/med/TOPIC1813.HTM. Retrieved on November 3, 2008.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 Olmedo R (2002). "Chapter 69: Phencyclidine and ketamine". In Goldfrank LR, Flomenbaum NE, Lewin NA, Howland MA, Hoffman RS, Nelson LS (eds.). Goldfrank's Toxicologic Emergencies. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 1034–41. ISBN 0-07-136001-8. http://books.google.com/?id=HVYyRsuUEc0C&pg=PA1041. Retrieved on November 3, 2008 through Google Book Search.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Milhorn HT (April 1991). "Diagnosis and management of phencyclidine intoxication". American Family Physician 43 (4): 1293–302. PMID 2008817.

- ↑ Giannini AJ. Price WA. PCP: Management of acute intoxication. Medical Times. 1985;113(9):43-49

- ↑ Giannini AJ, Eighan MS, Loiselle RH, Giannini MC (April 1984). "Comparison of haloperidol and chlorpromazine in the treatment of phencyclidine psychosis". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 24 (4): 202–4. PMID 6725621. http://jcp.sagepub.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=6725621.

External links

|

Recreational drug use |

|

| Major Recreational Drugs |

|

|

|

|

|

Depressants

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Entactogens

|

|

|

|

Hallucinogens

|

|

Psychedelics

|

|

|

|

Dissociatives

|

|

|

|

Deliriants

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Culture and Related Topics |

|

|

420 · Stoner Film · Spiritual Use of Cannabis · Medical Cannabis · Cannabis Cultivation · Cannabis smoking

|

|

|

Psychedelic

|

Art · Drug · Experience · Literature · Music

|

|

|

Other

|

Counterculture of the 1960s · Club Drug · Dance Party · Drug Tourism · Drug Paraphernalia · Hippie · Party and Play · Poly Drug Use · Rave · Self-medication · Sex and Drugs · Spiritual use of drugs |

|

|

| Problems with Drug Use |

Abuse · Addiction (Prevention · Opioid Replacement Therapy · Rehabilitation · Responsible Use) · Drug-related crime · Illegal Trade · Overdose |

|

| Legality of Drug Use |

|

International

|

1961 Narcotic Drugs · 1971 Psychotropic Substances · 1988 Drug Trafficking

|

|

|

State Level

|

Drug Policy (Prohibition · Supply reduction · Decriminalization) · Policy Reform (Liberalization · Harm Reduction · Demand Reduction)

|

|

|

Other

|

Designer Drug · Drug Possession · Drug Test · Hard and Soft Drugs · Narc · War on Drugs · Mexican Drug War |

|

|

| Lists of Countries by... |

Alcohol Consumption · Cannabis Legality (Annual Use · Lifetime Use) · Cocaine Use · Opiate Use · Cigarette Consumption

|

|

|

Analgesics (N02A, N02B) |

|

Opioids

See also: Opioids template |

|

Opium & alkaloids thereof

|

|

|

|

Semi-synthetic opium

derivatives

|

|

|

|

Synthetic opioids

|

|

|

|

| Pyrazolones |

Ampyrone/Aminophenazone · Metamizole · Phenazone · Propyphenazone

|

|

| Cannabinoids |

|

|

| Anilides |

|

|

Non-steroidal

anti-inflammatories

See also: NSAIDs template |

|

Propionic acid class

|

Fenoprofen · Flurbiprofen · Ibuprofen · Ketoprofen · Naproxen · Oxaprozin

|

|

|

Oxicam class

|

|

|

|

Acetic acid class

|

|

|

|

COX-2 inhibitors

|

Celecoxib · Rofecoxib · Valdecoxib · Parecoxib · Lumiracoxib

|

|

|

Anthranilic acid

(fenamate) class

|

Meclofenamate · Mefenamic acid

|

|

|

|

Aspirin (Acetylsalicylic acid) · Benorylate · Diflunisal · Ethenzamide · Magnesium salicylate · Salicin · Salicylamide · Salsalate · Trisalate · Wintergreen (Methyl salicylate)

|

|

|

Atypical, Adjuvant & Potentiators,

Metabolic agents and miscellaneous |

|

|

|

|

anat(s,m,p,,e,b,d,c,,f,,g)/phys/devp/cell

|

noco(m,d,e,h,v,s)/cong/tumr,sysi/,injr

|

proc,drug(N1A/2AB/C/3/4/7A/B//)

|

|

|

|

|

Depressants |

|

Antihistamines

H1R inverse agonists |

|

|

Antipsychotics

Mixed MOA |

|

|

| Channel Blockers |

Carbamazepine • Ethosuximide • Gabapentin • Lamotrigine • Oxcarbazepine • Phenytoin • Pregabalin • Topiramate • Zonisamide |

|

Dissociatives

NMDAR Antagonists |

|

Arylcyclohexylamines

|

3-MeO-PCP • Esketamine • Dieticyclidine • Eticyclidine • Gacyclidine • Ketamine • Phencyclidine • PCPr • Rolicyclidine • Tenocyclidine • Tiletamine |

|

|

Morphinans

|

|

|

|

Others

|

|

|

|

| GABAergics |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Carbamates

|

Carisoprodol • Felbamate • Meprobamate ...

|

|

|

|

1,4-BD • Aceburic Acid • Gabaculine • GBL • GABA • GABOB • GHB • GHV • GVL • Isovaleramide • Isovaleric Acid • Phenibut • Picamilon • Tiagabine • Valeric Acid • Valerenic Acid • Valnoctamide • Valproic Acid (Sodium Valproate / Valproate Semisodium) • Valpromide • Vigabatrin

|

|

|

Neuroactive Steroids

|

Alfaxalone • Allopregnanolone • Ganaxolone • Tetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone ...

|

|

|

Nonbenzodiazepines

|

|

|

|

Piperidinediones

|

Glutethimide ...

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Quinazolinones

|

|

|

|

Others

|

|

|

|

| Glycinergics |

Alanine • Cycloserine • Dimethylglycine • Glycine • Hypotaurine • Methylglycine / Sarcosine • Serine • Taurine • Trimethylglycine / Betaine

|

|

Narcotics

MOR Agonists |

|

|

Sympatholytics

α/β-AR Modulators |

|

Alpha Blockers

|

Doxazosin • Phentolamine • Prazosin • Tamsulosin • Urapidil ...

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Others

|

|

|

|

| Miscellaneous |

|

|

|

Hallucinogens |

|

Psychedelics

5-HT2AR agonists |

Lysergamides: AL-LAD • ALD-52 • BU-LAD • CYP-LAD • DAM-57 • Diallyllysergamide • Ergometrine (Ergonovine, Ergobasine) • ETH-LAD • LAE-32 • LSA (Ergine, Lysergamide) • LSD • LSH • LPD-824 • LSM-775 • Lysergic Acid 2-Butyl Amide • Lysergic Acid 2,4-Dimethylazetidide • Methylergometrine • Methylisopropyllysergamide • Methysergide • MLD-41 • PARGY-LAD • PRO-LAD;

Phenethylamines: Aleph • 2C-B • 2C-B-FLY • 2CBFly-NBOMe • 2C-C • 2C-D • 2CD-5EtO • 2C-E • 2C-F • 2C-G • 2C-I • 2C-N • 2C-O • 2C-O-4 • 2C-P • 2C-T • 2C-T-2 • 2C-T-4 • 2C-T-7 • 2C-T-8 • 2C-T-9 • 2C-T-13 • 2C-T-15 • 2C-T-17 • 2C-T-21 • 2C-TFM • 2C-YN • 2CBCB-NBOMe • 25B-NBOMe • 25I-NBMD • 25I-NBOH • 25I-NBOMe • 3C-E • 3C-P • Br-DFLY • DESOXY • DMMDA • DMMDA-2 • DOB • DOC • DOEF • DOET • DOF • DOI • DOM • DON • DOPR • DOTFM • Escaline • Ganesha • HOT-2 • HOT-7 • HOT-17 • IAP • Isoproscaline • Jimscaline • Lophophine • MDA • MDEA • MDMA • MMA • MMDA • MMDA-2 • MMDA-3a • MMDMA • Macromerine • Mescaline • Methallylescaline • Proscaline • TCB-2 • TFMFly • TMA;

Piperazines: pFPP • TMFPP;

Tryptamines: 1-Methyl-5-methoxy-diisopropyltryptamine • 2,N,N-TMT • 4,N,N-TMT • 4-HO-5-MeO-DMT • 4-Acetoxy-DET • 4-Acetoxy-DIPT • 4-Acetoxy-DMT • 4-Acetoxy-DPT • 4-Acetoxy-MiPT • 4-HO-DPT • 4-HO-MET • 4-Propionyloxy-DMT • 4-Hydroxy-N-Methyl-(α,N-trimethylene)tryptamine • 5-Me-MIPT • 5-N,N-TMT • 5-AcO-DMT • 5-MeO-2,N,N-TMT • 5-MeO-4,N,N-TMT • 5-MeO-α,N,N-TMT • 5-MeO-α-ET • 5-MeO-α-MT • 5-MeO-DALT • 5-MeO-DET • 5-MeO-DIPT • 5-MeO-DMT • 5-MeO-DPT • 5-MeO-EiPT • 5-MeO-MET • 5-MeO-MIPT • 5-Methoxy-N-methyl-(α,N-trimethylene)tryptamine • 7,N,N-TMT • α,N,N-TMT • α-ET • α-MT • AL-37350A • Baeocystin • Bufotenin • DALT • DBT • DET • DIPT • DMT • DPT • EiPT • Ethocin • Ethocybin • Iprocin • MET • Miprocin • MIPT • Norbaeocystin • PiPT • Psilocin • Psilocybin;

Others: AL-38022A • Ibogaine • Noribogaine • Voacangine

|

|

Dissociatives

NMDAR antagonists |

Adamantanes: Amantadine • Memantine • Rimantadine;

Arylcyclohexylamines: 3-MeO-PCP • 4-MeO-PCP • Dieticyclidine • Esketamine • Eticyclidine • Gacyclidine • Ketamine • Methoxetamine • Neramexane • Phencyclidine • PCPr • Rolicyclidine • Tenocyclidine • Tiletamine;

Morphinans: Dextrallorphan • Dextromethorphan • Dextrorphan • Methorphan (Racemethorphan) • Morphan (Racemorphan);

Others: 2-MDP • 8A-PDHQ • Aptiganel • Dexoxadrol • Dizocilpine (MK-801) • Etoxadrol • Ibogaine • Midafotel • NEFA • Nitrous Oxide • Noribogaine • Perzinfotel • Remacemide • Selfotel • Xenon

|

|

Deliriants

mAChR antagonists |

3-Quinuclidinyl benzilate • Atropine • Benactyzine • Benzatropine • Benzydamine • Biperiden • Brompheniramine • CAR-226,086 • CAR-301,060 • CAR-302,196 • CAR-302,282 • CAR-302,368 • CAR-302,537 • CAR-302,668 • Chlorpheniramine • Chloropyramine • Clemastine • CS-27349 • Cyclizine • Cyproheptadine • Dicyclomine (Dicycloverine) • Dimenhydrinate • Diphenhydramine • Ditran • Doxylamine • EA-3167 • EA-3443 • EA-3580 • EA-3834 • Elemicin • Flavoxate • Hydroxyzine • Hyoscyamine • Meclizine • Myristicin • N-Ethyl-3-piperidyl benzilate • N-Methyl-3-piperidyl benzilate • Pyrilamine • Orphenadrine • Oxybutynin • Pheniramine • Phenyltoloxamine • Procyclidine • Promethazine • Scopolamine (Hyoscine) • Tolterodine • Trihexyphenidyl • Tripelennamine • Triprolidine • WIN-2299

|

|

| Miscellaneous |

|

|

Cannabinol • CP-47,497 • CP-55,244 • CP-55,940 • DMHP • HU-210 • JWH-018 • JWH-030 • JWH-073 • JWH-081 • JWH-200 • JWH-250 • Nabilone • Nabitan • Nantradol • Parahexyl • THC (Dronabinol) • WIN-55,212-2

|

|

|

D2R agonists

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2-EMSB • 2-MMSB • Alazocine • Bremazocine • Butorphanol • Cyclazocine • Cyprenorphine • Dextrallorphan • Dezocine • Enadoline • Herkinorin • HZ-2 • Ibogaine • Ketazocine • Metazocine • Nalbuphine • Nalorphine • Noribogaine • Pentazocine • Phenazocine • Salvinorin A • Spiradoline • Tifluadom • U-50,488 • U-69,593

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Others

|

Efavirenz • Glaucine • Isoaminile

|

|

|

|

Stimulants |

|

| Adamantanes |

Adaphenoxate • Adapromine • Amantadine • Bromantane • Chlodantane • Gludantane • Memantine • Midantane

|

|

| Arylcyclohexylamines |

Benocyclidine • Dieticyclidine • Esketamine • Eticyclidine • Gacyclidine • Ketamine • Phencyclamine • Phencyclidine • Rolicyclidine • Tenocyclidine • Tiletamine

|

|

| Benzazepines |

6-Br-APB • SKF-77434 • SKF-81297 • SKF-82958

|

|

| Cholinergics |

A-84543 • A-366,833 • ABT-202 • ABT-418 • AR-R17779 • Altinicline • Anabasine • Arecoline • Cotinine • Cytisine • Dianicline • Epibatidine • Epiboxidine • GTS-21 • Ispronicline • Nicotine • PHA-543,613 • PNU-120,596 • PNU-282,987 • Pozanicline • Rivanicline • Sazetidine A • SIB-1553A • SSR-180,711 • TC-1698 • TC-1827 • TC-2216 • TC-5619 • Tebanicline • UB-165 • Varenicline • WAY-317,538

|

|

| Convulsants |

Anatoxin-a • Bicuculline • DMCM • Flurothyl • Gabazine • Pentetrazol • Picrotoxin • Strychnine • Thujone

|

|

| Eugeroics |

Adrafinil • Armodafinil • CRL-40941 • Modafinil

|

|

| Oxazolines |

4-Methylaminorex • Aminorex • Clominorex • Cyclazodone • Fenozolone • Fluminorex • Pemoline • Thozalinone

|

|

| Phenethylamines |

1-(4-Methylphenyl)-2-aminobutane • 2-Fluoroamphetamine • 2-Fluoromethamphetamine • 2-OH-PEA • 2-Phenyl-3-aminobutane • 2-Phenyl-3-methylaminobutane • 2,3-MDA • 3-Fluoroamphetamine • 3-Fluoroethamphetamine • 3-Fluoromethcathinone • 3-Methoxyamphetamine • 3-Methylamphetamine • 4-BMC • 4-Ethylamphetamine • 4-FA • 4-FMA • 4-MA • 4-MMA • 4-MTA • 6-FNE • Alfetamine • α-Ethylphenethylamine • Amfecloral • Amfepentorex • Amfepramone • Amidephrine • Amphetamine (Dextroamphetamine, Levoamphetamine) • Amphetaminil • Arbutamine • Atomoxetine (Tomoxetine) • β-Methylphenethylamine • β-Phenylmethamphetamine • Benfluorex • Benzphetamine • BDB (J) • BOH (Hydroxy-J) • BPAP • Buphedrone • Bupropion (Amfebutamone) • Butylone • Cathine • Cathinone • Chlorphentermine • Clenbuterol • Clobenzorex • Cloforex • Clortermine • D-Deprenyl • Denopamine • Dimethoxyamphetamine • Dimethylamphetamine • Dimethylcathinone (Dimethylpropion, Metamfepramone) • Dobutamine • DOPA (Dextrodopa, Levodopa) • Dopamine • Dopexamine • Droxidopa • EBDB (Ethyl-J) • Ephedrine • Epinephrine (Adrenaline) • Epinine (Deoxyepinephrine) • Etafedrine • Ethcathinone (Ethylpropion) • Ethylamphetamine (Etilamfetamine) • Ethylnorepinephrine (Butanefrine) • Ethylone • Etilefrine • Famprofazone • Fenbutrazate • Fencamine • Fencamfamine • Fenethylline • Fenfluramine (Dexfenfluramine) • Fenmetramide • Fenproporex • Flephedrone • Fludorex • Furfenorex • Gepefrine • HMMA • Hordenine • Ibopamine • IMP • Indanylamphetamine • Isoetarine • Isoprenaline (Isoproterenol) • L-Deprenyl (Selegiline) • Lefetamine • Lisdexamfetamine • Lophophine (Homomyristicylamine) • Manifaxine • MBDB (Methyl-J; "Eden") • MDA (Tenamfetamine) • MDBU • MDEA ("Eve") • MDMA ("Ecstasy", "Adam") • MDMPEA (Homarylamine) • MDOH • MDPR • MDPEA (Homopiperonylamine) • Mefenorex • Mephedrone • Mephentermine • Metanephrine • Metaraminol • Methamphetamine (Desoxyephedrine, Methedrine; Dextromethamphetamine, Levomethamphetamine) • Methoxamine • Methoxyphenamine • MMA • Methcathinone (Methylpropion) • Methedrone • Methoxyphenamine • Methylone • MMDA • MMDMA • MMMA • Morazone • Naphthylamphetamine • Nisoxetine • Norepinephrine (Noradrenaline) • Norfenefrine • Norfenfluramine • Normetanephrine • Octopamine • Orciprenaline • Ortetamine • Oxilofrine • Paredrine (Norpholedrine, Oxamphetamine, Mycadrine) • PBA • PCA • PHA • Pargyline • Pentorex (Phenpentermine) • Pentylone • Phendimetrazine • Phenmetrazine • Phenpromethamine • Phentermine • Phenylalanine • Phenylephrine (Neosynephrine) • Phenylpropanolamine • Pholedrine • PIA • PMA • PMEA • PMMA • PPAP • Prenylamine • Propylamphetamine • Pseudoephedrine • Radafaxine • Ropinirole • Salbutamol (Albuterol; Levosalbutamol) • Sibutramine • Synephrine (Oxedrine) • Theodrenaline • Tiflorex (Flutiorex) • Tranylcypromine • Tyramine • Tyrosine • Xamoterol • Xylopropamine • Zylofuramine

|

|

| Piperazines |

2C-B-BZP • BZP • CM156 • DBL-583 • GBR-12783 • GBR-12935 • GBR-13069 • GBR-13098 • GBR-13119 • MeOPP • MBZP • Vanoxerine

|

|

| Piperidines |

1-Benzyl-4-(2-(diphenylmethoxy)ethyl)piperidine • 2-Benzylpiperidine • 3,4-Dichloromethylphenidate • 4-Benzylpiperidine • 4-Methylmethylphenidate • Desoxypipradrol • Difemetorex • Diphenylpyraline • Ethylphenidate • Methylnaphthidate • Methylphenidate (Dexmethylphenidate) • Nocaine • Phacetoperane • Pipradrol • SCH-5472

|

|

| Pyrrolidines |

α-PPP • α-PBP • α-PVP • MDPPP • MDPBP • MDPV • MPBP • MPHP • MPPP • MOPPP • Naphyrone • PEP • Prolintane • Pyrovalerone

|

|

| Tropanes |

3-CPMT • 3-Pseudotropyl-4-fluorobenzoate • 4'-Fluorococaine • AHN-1055 • Altropane (IACFT) • Brasofensine • CFT (WIN 35,428) • β-CIT (RTI-55) • Cocaethylene • Cocaine • Dichloropane (RTI-111) • Difluoropine • FE-β-CPPIT • FP-β-CPPIT • Ioflupane (123I) • Norcocaine • PIT • PTT • RTI-31 • RTI-32 • RTI-51 • RTI-105 • RTI-112 • RTI-113 • RTI-117 • RTI-121 (IPCIT) • RTI-126 • RTI-150 • RTI-154 • RTI-171 • RTI-177 • RTI-183 • RTI-194 • RTI-202 • RTI-229 • RTI-241 • RTI-336 • RTI-354 • RTI-371 • RTI-386 • Salicylmethylecgonine • Tesofensine • Troparil (β-CPT, WIN 35,065-2) • Tropoxane • WF-23 • WF-33 • WF-60

|

|

| Xanthines |

|

|

| Others |

1-(Thiophen-2-yl)-2-aminopropane • 2-Amino-1,2-dihydronaphthalene • 2-Aminoindane • 2-Aminotetralin • 2-Diphenylmethylpyrrolidine • 2-MDP • 3,3-Diphenylcyclobutanamine • 5-(2-Aminopropyl)indole • 5-Iodo-2-aminoindane • AL-1095 • Amfonelic acid • Amineptine • Amiphenazole • Atipamezole • Bemegride • Benzydamine • BTQ • BTS 74,398 • Carphedon • Ciclazindol • Cilobamine • Clofenciclan • Cropropamide • Crotetamide • Diclofensine • Dimethocaine • Diphenylprolinol • Efaroxan • Etamivan • EXP-561 • Fenpentadiol • Feprosidnine • Gamfexine • Gilutensin • GYKI-52895 • Hexacyclonate • Idazoxan • Indanorex • Indatraline • JNJ-7925476 • JZ-IV-10 • Lazabemide • Leptacline • Levopropylhexedrine • Lomevactone • LR-5182 • Mazindol • Meclofenoxate • Medifoxamine • Mefexamide • Mesocarb • Methastyridone • Nefopam • Nikethamide • Nomifensine • O-2172 • Oxaprotiline • Phthalimidopropiophenone • PNU-99,194 • Propylhexedrine • PRC200-SS • Rasagiline • Rauwolscine • Rubidium chloride • Setazindol • Tametraline • Tandamine • Trazium • UH-232 • Yohimbine

|

|

| See also |

|

|

Anesthetic: General anesthetics (N01A) |

|

| Inhalation |

|

|

Diethyl ether • Methoxypropane • Vinyl ether • halogenated ethers (Desflurane • Enflurane • Isoflurane • Methoxyflurane • Sevoflurane)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Others

|

|

|

|

| Injection |

|

|

Hexobarbital • Methohexital • Narcobarbital • Thiopental# |

|

|

|

Alfentanil • Anileridine • Fentanyl • Phenoperidine • Remifentanil • Sufentanil |

|

|

Neuroactive steroids

|

Alfaxalone • Minaxolone

|

|

|

Others

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

anat(s,m,p,,e,b,d,c,,f,,g)/phys/devp/cell

|

noco(m,d,e,h,v,s)/cong/tumr,sysi/,injr

|

proc,drug(N1A/2AB/C/3/4/7A/B//)

|

|

|

|

|

Cholinergics |

|

|

Receptor ligands |

|

|

mAChR

|

Agonists: 77-LH-28-1 · AC-42 · AC-260,584 · Aceclidine · Acetylcholine · AF30 · AF150(S) · AF267B · AFDX-384 · Alvameline · AQRA-741 · Arecoline · Bethanechol · Butyrylcholine · Carbachol · CDD-0034 · CDD-0078 · CDD-0097 · CDD-0098 · CDD-0102 · Cevimeline · cis-Dioxolane · Ethoxysebacylcholine · LY-593,039 · L-689,660 · LY-2,033,298 · McNA343 · Methacholine · Milameline · Muscarine · NGX-267 · Ocvimeline · Oxotremorine · PD-151,832 · Pilocarpine · RS86 · Sabcomeline · SDZ 210-086 · Sebacylcholine · Suberylcholine · Talsaclidine · Tazomeline · Thiopilocarpine · Vedaclidine · VU-0029767 · VU-0090157 · VU-0152099 · VU-0152100 · VU-0238429 · WAY-132,983 · Xanomeline · YM-796

Antagonists: 3-Quinuclidinyl Benzilate · 4-DAMP · Aclidinium Bromide · Anisodamine · Anisodine · Atropine · Atropine Methonitrate · Benactyzine · Benzatropine (Benztropine) · Benzydamine · BIBN 99 · Biperiden · Bornaprine · CAR-226,086 · CAR-301,060 · CAR-302,196 · CAR-302,282 · CAR-302,368 · CAR-302,537 · CAR-302,668 · CS-27349 · Cyclobenzaprine · Cyclopentolate · Darifenacin · DAU-5884 · Dimethindene · Dexetimide · DIBD · Dicyclomine (Dicycloverine) · Ditran · EA-3167 · EA-3443 · EA-3580 · EA-3834 · Elemicin · Etanautine · Etybenzatropine (Ethylbenztropine) · Flavoxate · Himbacine · HL-031,120 · Ipratropium · J-104,129 · Hyoscyamine · Mamba Toxin 3 · Mamba Toxin 7 · Mazaticol · Mebeverine · Methoctramine · Metixene · Myristicin · N-Ethyl-3-Piperidyl Benzilate · N-Methyl-3-Piperidyl Benzilate · Orphenadrine · Otenzepad · Oxybutynin · PBID · PD-102,807 · Phenglutarimide · Phenyltoloxamine · Pirenzepine · Piroheptine · Procyclidine · Profenamine · RU-47,213 · SCH-57,790 · SCH-72,788 · SCH-217,443 · Scopolamine (Hyoscine) · Solifenacin · Telenzepine · Tiotropium · Tolterodine · Trihexyphenidyl · Tripitamine · Tropatepine · Tropicamide · WIN-2299 · Xanomeline · Zamifenacin; Others: 1st Generation Antihistamines (Brompheniramine, chlorpheniramine, cyproheptadine, dimenhydrinate, diphenhydramine, doxylamine, mepyramine/pyrilamine, phenindamine, pheniramine, tripelennamine, triprolidine, etc) · Tricyclic Antidepressants ( Amitriptyline, doxepin, trimipramine, etc) · Tetracyclic Antidepressants (Amoxapine, maprotiline, etc) · Typical Antipsychotics ( Chlorpromazine, thioridazine, etc) · Atypical Antipsychotics ( Clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, etc)

|

|

|

nAChR

|

Agonists: 5-HIAA · A-84,543 · A-366,833 · A-582,941 · A-867,744 · ABT-202 · ABT-418 · ABT-560 · ABT-894 · Acetylcholine · Altinicline · Anabasine · AR-R17779 · Butyrylcholine · Carbachol · Cotinine · Cytisine · Decamethonium · Desformylflustrabromine · Dianicline · Dimethylphenylpiperazinium · Epibatidine · Epiboxidine · Ethanol · Ethoxysebacylcholine · EVP-4473 · EVP-6124 · Galantamine · GTS-21 · Ispronicline · Lobeline · MEM-63,908 (RG-3487) · Nicotine · NS-1738 · PHA-543,613 · PHA-709,829 · PNU-120,596 · PNU-282,987 · Pozanicline · Rivanicline · Sazetidine A · Sebacylcholine · SIB-1508Y · SIB-1553A · SSR-180,711 · Suberylcholine · TC-1698 · TC-1734 · TC-1827 · TC-2216 · TC-5214 · TC-5619 · TC-6683 · Tebanicline · Tropisetron · UB-165 · Varenicline · WAY-317,538 · XY-4083

Antagonists: 18-Methoxycoronaridine · α-Bungarotoxin · α-Conotoxin · Alcuronium · Amantadine · Anatruxonium · Atracurium · Bupropion (Amfebutamone) · Chandonium · Chlorisondamine · Cisatracurium · Coclaurine · Coronaridine · Dacuronium · Decamethonium · Dextromethorphan · Dextropropoxyphene · Dextrorphan · Diadonium · DHβE · Dimethyltubocurarine (Metocurine) · Dipyrandium · Dizocilpine (MK-801) · Doxacurium · Duador · Esketamine · Fazadinium · Gallamine · Hexafluronium · Hexamethonium (Benzohexonium) · Ibogaine · Isoflurane · Ketamine · Kynurenic acid · Laudexium (Laudolissin) · Levacetylmethadol · Malouetine · Mecamylamine · Memantine · Methadone · Methorphan (Racemethorphan) · Methyllycaconitine · Metocurine · Mivacurium · Morphanol (Racemorphanol) · Neramexane · Nitrous Oxide · Pancuronium · Pempidine · Pentamine · Pentolinium · Phencyclidine · Pipecuronium · Radafaxine · Rapacuronium · Rocuronium · Surugatoxin · Suxamethonium (Succinylcholine) · Thiocolchicoside · Toxiferine · Trimethaphan · Tropeinium · Tubocurarine · Vecuronium · Xenon

|

|

|

|

|

Reuptake inhibitors |

|

|

|

|

CHT Inhibitors

|

Hemicholinium-3 (Hemicholine; HC3) · Triethylcholine

|

|

|

|

Vesicular

|

|

VAChT Inhibitors

|

Vesamicol

|

|

|

|

|

|

Enzyme inhibitors |

|

|

|

|

ChAT inhibitors

|

1-(-Benzoylethyl)pyridinium · 2-(α-Naphthoyl)ethyltrimethylammonium · 3-Chloro-4-stillbazole · 4-(1-Naphthylvinyl)pyridine · Acetylseco hemicholinium-3 · Acryloylcholine · AF64A · B115 · BETA · CM-54,903 · N,N-Dimethylaminoethylacrylate · N,N-Dimethylaminoethylchloroacetate

|

|

|

|

|

|

AChE inhibitors

|

Reversible: Carbamates: Aldicarb · Bendiocarb · Bufencarb · Carbaryl · Carbendazim · Carbetamide · Carbofuran · Chlorbufam · Chloropropham · Ethienocarb · Ethiofencarb · Fenobucarb · Fenoxycarb · Formetanate · Furadan · Ladostigil · Methiocarb · Methomyl · Miotine · Oxamyl · Phenmedipham · Pinmicarb · Pirimicarb · Propamocarb · Propham · Propoxur; Stigmines: Ganstigmine · Neostigmine · Phenserine · Physostigmine · Pyridostigmine · Rivastigmine; Others: Acotiamide · Ambenonium · Donepezil · Edrophonium · Galantamine · Huperzine A · Minaprine · Tacrine · Zanapezil

Irreversible: Organophosphates: Acephate · Azinphos-methyl · Bensulide · Cadusafos · Chlorethoxyfos · Chlorfenvinphos · Chlorpyrifos · Chlorpyrifos-Methyl · Coumaphos · Cyclosarin (GF) · Demeton · Demeton-S-Methyl · Diazinon · Dichlorvos · Dicrotophos · Diisopropyl fluorophosphate (Guthion) · Diisopropylphosphate · Dimethoate · Dioxathion · Disulfoton · EA-3148 · Echothiophate · Ethion · Ethoprop · Fenamiphos · Fenitrothion · Fenthion · Fosthiazate · GV · Isofluorophate · Isoxathion · Malaoxon · Malathion · Methamidophos · Methidathion · Metrifonate · Mevinphos · Monocrotophos · Naled · Novichok agent · Omethoate · Oxydemeton-Methyl · Paraoxon · Parathion · Parathion-Methyl · Phorate · Phosalone · Phosmet · Phostebupirim · Phoxim · Pirimiphos-Methyl · Sarin (GB) · Soman (GD) · Tabun (GA) · Temefos · Terbufos · Tetrachlorvinphos · Tribufos · Trichlorfon · VE · VG · VM · VR · VX; Others: Demecarium · Onchidal ( Onchidella binneyi)

|

|

|

BChE inhibitors

|

* Many of the acetylcholinesterase inhibitors listed above act as butyrylcholinesterase inhibitors.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Others |

|

|

Precursors

|

Choline (Lecithin) · Citicoline · Cyprodenate · Dimethylethanolamine (DMAE, deanol) · Glycerophosphocholine · Meclofenoxate (Centrophenoxine) · Phosphatidylcholine · Phosphatidylethanolamine · Phosphorylcholine · Pirisudanol

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Others

|

Acetylcholine releasing agents: α-Latrotoxin · β-Bungarotoxin; Acetylcholine release inhibitors: Botulinum toxin (Botox); Acetylcholinesterase reactivators: Asoxime · Obidoxime · Pralidoxime

|

|

|

|

|

Dopaminergics |

|

|

Receptor ligands |

|

|

Agonists

|

Adamantanes: Amantadine • Memantine • Rimantadine; Aminotetralins: 7-OH-DPAT • 8-OH-PBZI • Rotigotine • UH-232; Benzazepines: 6-Br-APB • Fenoldopam • SKF-38,393 • SKF-77,434 • SKF-81,297 • SKF-82,958 • SKF-83,959; Ergolines: Bromocriptine • Cabergoline • Dihydroergocryptine • Lisuride • LSD • Pergolide; Dihydrexidine derivatives: 2-OH-NPA • A-86,929 • Ciladopa • Dihydrexidine • Dinapsoline • Dinoxyline • Doxanthrine; Others: A-68,930 • A-77,636 • A-412,997 • ABT-670 • ABT-724 • Aplindore • Apomorphine • Aripiprazole • Bifeprunox • BP-897 • CY-208,243 • Dizocilpine • Etilevodopa • Flibanserin • Ketamine • Melevodopa • Modafinil • Pardoprunox • Phencyclidine • PD-128,907 • PD-168,077 • PF-219,061 • Piribedil • Pramipexole • Propylnorapomorphine • Pukateine • Quinagolide • Quinelorane • Quinpirole • RDS-127 • Ro10-5824 • Ropinirole • Rotigotine • Roxindole • Salvinorin A • SKF-89,145 • Sumanirole • Terguride • Umespirone • WAY-100,635

|

|

|

Antagonists

|

Typical antipsychotics: Acepromazine • Azaperone • Benperidol • Bromperidol • Clopenthixol • Chlorpromazine • Chlorprothixene • Droperidol • Flupentixol • Fluphenazine • Fluspirilene • Haloperidol • Loxapine • Mesoridazine • Methotrimeprazine • Nemonapride • Penfluridol • Perazine • Periciazine • Perphenazine • Pimozide • Prochlorperazine • Promazine • Sulforidazine • Sulpiride • Sultopride • Thioridazine • Thiothixene • Trifluoperazine • Triflupromazine • Trifluperidol • Zuclopenthixol; Atypical antipsychotics: Amisulpride • Asenapine • Blonanserin • Carpipramine • Clocapramine • Clozapine • Gevotroline • Iloperidone • Lurasidone • Melperone • Molindone • Mosapramine • Ocaperidone • Olanzapine • Paliperidone • Perospirone • Piquindone • Quetiapine • Remoxipride • Risperidone • Sertindole • Tiospirone • Ziprasidone • Zotepine; Antiemetics: AS-8112 • Alizapride • Bromopride • Clebopride • Domperidone • Metoclopramide • Thiethylperazine; Others: Amoxapine • Buspirone • Butaclamol • Ecopipam • EEDQ • Eticlopride • Fananserin • L-745,870 • Nafadotride • Nuciferine • PNU-99,194 • Raclopride • Sarizotan • SB-277,011-A • SCH-23,390 • SKF-83,566 • SKF-83,959 • Sonepiprazole • Spiperone • Spiroxatrine • Stepholidine • Tetrahydropalmatine • Tiapride • UH-232 • Yohimbine

|

|

|

|

|

Reuptake inhibitors |

|

|

|

|

DAT inhibitors

|

Piperazines: DBL-583 • GBR-12,935 • Nefazodone • Vanoxerine; Piperidines: BTCP • Desoxypipradrol • Dextromethylphenidate • Difemetorex • Ethylphenidate • Methylnaphthidate • Methylphenidate • Phencyclidine • Pipradrol; Pyrrolidines: Diphenylprolinol • Methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) • Naphyrone • Prolintane • Pyrovalerone; Tropanes: β-CPPIT • Altropane • Brasofensine • CFT • Cocaine • Dichloropane • Difluoropine • FE-β-CPPIT • FP-β-CPPIT • Ioflupane ( 123I) • Iometopane • RTI-112 • RTI-113 • RTI-121 • RTI-126 • RTI-150 • RTI-177 • RTI-229 • RTI-336 • Tenocyclidine • Tesofensine • Troparil • Tropoxane • WF-11 • WF-23 • WF-31 • WF-33; Others: Adrafinil • Armodafinil • Amfonelic acid • Amineptine • Benzatropine (Benztropine) • Bromantane • BTQ • BTS-74,398 • Bupropion (Amfebutamone) • Ciclazindol • Diclofensine • Dimethocaine • Diphenylpyraline • Dizocilpine • DOV-102,677 • DOV-21,947 • DOV-216,303 • Etybenzatropine (Ethylbenztropine) • EXP-561 • Fencamine • Fencamfamine • Fezolamine • GYKI-52,895 • Indatraline • Ketamine • Lefetamine • Levophacetoperane • LR-5182 • Manifaxine • Mazindol • Medifoxamine • Mesocarb • Modafinil • Nefopam • Nomifensine • NS-2359 • O-2172 • Pridefrine • Propylamphetamine • Radafaxine • SEP-225,289 • SEP-227,162 • Sertraline • Sibutramine • Tametraline • Tripelennamine

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Releasing agents |

|

Morpholines: Fenbutrazate • Morazone • Phendimetrazine • Phenmetrazine; Oxazolines: 4-Methylaminorex (4-MAR, 4-MAX) • Aminorex • Clominorex • Cyclazodone • Fenozolone • Fluminorex • Pemoline • Thozalinone; Phenethylamines (also amphetamines, cathinones, phentermines, etc): 2-Hydroxyphenethylamine (2-OH-PEA) • 4-CAB • 4-Methylamphetamine (4-MA) • 4-Methylmethamphetamine (4-MMA) • Alfetamine • Amfecloral • Amfepentorex • Amfepramone • Amphetamine ( Dextroamphetamine, Levoamphetamine) • Amphetaminil • β-Methylphenethylamine (β-Me-PEA) • Benzodioxolylbutanamine (BDB) • Benzodioxolylhydroxybutanamine (BOH) • Benzphetamine • Buphedrone • Butylone • Cathine • Cathinone • Clobenzorex • Clortermine • D-Deprenyl • Dimethoxyamphetamine (DMA) • Dimethoxymethamphetamine (DMMA) • Dimethylamphetamine • Dimethylcathinone (Dimethylpropion, metamfepramone) • Ethcathinone (Ethylpropion) • Ethylamphetamine • Ethylbenzodioxolylbutanamine (EBDB) • Ethylone • Famprofazone • Fenethylline • Fenproporex • Flephedrone • Fludorex • Furfenorex • Hordenine • Lophophine (Homomyristicylamine) • Mefenorex • Mephedrone • Methamphetamine (Desoxyephedrine, Methedrine; Dextromethamphetamine, Levomethamphetamine) • Methcathinone (Methylpropion) • Methedrone • Methoxymethylenedioxyamphetamine (MMDA) • Methoxymethylenedioxymethamphetamine (MMDMA) • Methylbenzodioxolylbutanamine (MBDB) • Methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA, tenamfetamine) • Methylenedioxyethylamphetamine (MDEA) • Methylenedioxyhydroxyamphetamine (MDOH) • Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) • Methylenedioxymethylphenethylamine (MDMPEA, homarylamine) • Methylenedioxyphenethylamine (MDPEA, homopiperonylamine) • Methylone • Ortetamine • Parabromoamphetamine (PBA) • Parachloroamphetamine (PCA) • Parafluoroamphetamine (PFA) • Parafluoromethamphetamine (PFMA) • Parahydroxyamphetamine (PHA) • Paraiodoamphetamine (PIA) • Paredrine (Norpholedrine, Oxamphetamine) • Phenethylamine (PEA) • Pholedrine • Phenpromethamine • Prenylamine • Propylamphetamine • Tiflorex (Flutiorex) • Tyramine (TRA) • Xylopropamine • Zylofuramine; Piperazines: 2,5-Dimethoxy-4-bromobenzylpiperazine (2C-B-BZP) • Benzylpiperazine (BZP) • Methoxyphenylpiperazine (MeOPP, paraperazine) • Methylbenzylpiperazine (MBZP) • Methylenedioxybenzylpiperazine (MDBZP, piperonylpiperazine); Others: 2-Amino-1,2-dihydronaphthalene (2-ADN) • 2-Aminoindane (2-AI) • 2-Aminotetralin (2-AT) • 4-Benzylpiperidine (4-BP) • 5-IAI • Clofenciclan • Cyclopentamine • Cypenamine • Cyprodenate • Feprosidnine • Gilutensin • Heptaminol • Hexacyclonate • Indanylaminopropane (IAP) • Indanorex • Isometheptene • Methylhexanamine • Naphthylaminopropane (NAP) • Octodrine • Phthalimidopropiophenone • Propylhexedrine (Levopropylhexedrine) • Tuaminoheptane (Tuamine)

|

|

|

|

Enzyme inhibitors |

|

|

|

|

PAH inhibitors

|

3,4-Dihydroxystyrene

|

|

|

TH inhibitors

|

3-Iodotyrosine • Aquayamycin • Bulbocapnine • Metirosine • Oudenone

|

|

|

AAAD / DDC inhibitors

|

Benserazide • Carbidopa • Genistein • Methyldopa

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nonselective: Benmoxin • Caroxazone • Echinopsidine • Furazolidone • Hydralazine • Indantadol • Iproclozide • Iproniazid • Isocarboxazid • Isoniazid • Linezolid • Mebanazine • Metfendrazine • Nialamide • Octamoxin • Paraxazone • Phenelzine • Pheniprazine • Phenoxypropazine • Pivalylbenzhydrazine • Procarbazine • Safrazine • Tranylcypromine; MAO-A selective: Amiflamine • Bazinaprine • Befloxatone • Befol • Brofaromine • Cimoxatone • Clorgiline • Esuprone • Harmala alkaloids (Harmine, Harmaline, Tetrahydroharmine, Harman, Norharman, etc) • Methylene Blue • Metralindole • Minaprine • Moclobemide • Pirlindole • Sercloremine • Tetrindole • Toloxatone • Tyrima; MAO-B selective: D-Deprenyl • L-Deprenyl (Selegiline) • Ladostigil • Lazabemide • Milacemide • Mofegiline • Pargyline • Rasagiline

|

|

|

COMT inhibitors

|

Entacapone • Tolcapone

|

|

|

DBH inhibitors

|

Bupicomide • Disulfiram • Dopastin • Fusaric acid • Nepicastat • Phenopicolinic acid • Tropolone

|

|

|

|

|

|

Others |

|

|

Precursors

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Others

|

Activity Enhancers: Benzofuranylpropylaminopentane (BPAP) • Phenylpropylaminopentane (PPAP); Toxins: Oxidopamine (6-Hydroxydopamine)

|

|

|

|

|

Glutamatergics |

|

| Ionotropic |

|

AMPA

|

Agonists: 5-Fluorowillardiine • AMPA • Domoic acid • Quisqualic acid; Positive allosteric modulators: Aniracetam • Cyclothiazide • CX-516 • CX-546 • CX-614 • CX-691 • CX-717 • Diazoxide • HCTZ • IDRA-21 • LY-392,098 • LY-404,187 • LY-451,395 • LY-451,646 • LY-503,430 • Oxiracetam • PEPA • Piracetam • Pramiracetam • S-18986 • Sunifiram • Unifiram

Antagonists: ATPO • Barbiturates • Caroverine • CNQX • DNQX • GYKI-52466 • NBQX • Perampanel • Talampanel • Tezampanel • Topiramate; Negative allosteric modulators: GYKI-53,655

|

|

|

|

Agonists: Glutamate/acite site competitive agonists: Aspartate • Glutamate • Homoquinolinic acid • Ibotenic acid • NMDA • Quinolinic acid • Tetrazolylglycine; Glycine site agonists: ACBD • ACPC • ACPD • Alanine • CCG • Cycloserine • DHPG • Fluoroalanine • Glycine • HA-966 • L-687,414 • Milacemide • Sarcosine • Serine • Tetrazolylglycine; Polyamine site agonists: Acamprosate • Spermidine • Spermine

Antagonists: Competitive antagonists: AP5 (APV) • AP7 • CGP-37849 • CGP-39551 • CGP-39653 • CGP-40116 • CGS-19755 • CPP • LY-233,053 • LY-235,959 • LY-274,614 • MDL-100,453 • Midafotel (d-CPPene) • NPC-12,626 • NPC-17,742 • PBPD • PEAQX • Perzinfotel • PPDA • SDZ-220581 • Selfotel; Noncompetitive antagonists: ARR-15,896 • Caroverine • Dexanabinol • FPL-12495 • FR-115,427 • Hodgkinsine • Magnesium • MDL-27,266 • NPS-1506 • Psychotridine • Zinc; Uncompetitive pore blockers: 2-MDP • 3-MeO-PCP • 8A-PDHQ • Amantadine • Aptiganel • ARL-12,495 • ARL-15,896-AR • ARL-16,247 • Budipine • Delucemine • Dexoxadrol • Dextrallorphan • Dieticyclidine • Dizocilpine • Endopsychosin • Esketamine • Etoxadrol • Eticyclidine • Gacyclidine • Ibogaine • Indantadol • Ketamine • Ketobemidone • Loperamide • Memantine • Meperidine (Pethidine) • Methadone • Methorphan ( Dextromethorphan, Levomethorphan) • Methoxetamine • Milnacipran • Morphanol (Dextrorphan, Levorphanol) • NEFA • Neramexane • Nitrous oxide • Noribogaine • Orphenadrine • PCPr • Phencyclamine • Phencyclidine • Propoxyphene • Remacemide • Rhynchophylline • Riluzole • Rimantadine • Rolicyclidine • Sabeluzole • Tenocyclidine • Tiletamine • Tramadol • Xenon; Glycine site antagonists: ACEA-1021 • ACEA-1328 • ACPC • Carisoprodol • CGP-39653 • CKA • DCKA • Felbamate • Gavestinel • GV-196,771 • Kynurenic acid • L-689,560 • L-701,324 • Lacosamide • Licostinel • LU-73,068 • MDL-105,519 • Meprobamate • MRZ 2/576 • PNQX • ZD-9379; NR2B subunit antagonists: Besonprodil • CO-101,244 (PD-174,494) • CP-101,606 • Eliprodil • Haloperidol • Ifenprodil • Isoxsuprine • Nylidrin • Ro8-4304 • Ro25-6981 • Traxoprodil; Polyamine site antagonists: Arcaine • Co 101676 • Diaminopropane • Diethylenetriamine • Huperzine A • Putrescine • Ro 25-6981; Unclassified/unsorted antagonists: Chloroform • Diethyl ether • Enflurane • Ethanol (Alcohol) • Halothane • Isoflurane • Methoxyflurane • Toluene • Trichloroethane • Trichloroethanol • Trichloroethylene • Xylene

|

|

|

Kainate

|

Agonists: 5-Iodowillardiine • ATPA • Domoic acid • Kainic acid • LY-339,434 • SYM-2081

Antagonists: CNQX • DNQX • LY-382,884 • NBQX • NS102 • Tezampanel • Topiramate • UBP-302; Negative allosteric modulators: NS-3763

|

|

|

| Metabotropic |

|

Group I

|

Agonists: Unselective: ACPD • DHPG • Quisqualic acid; mGlu1-selective: Ro01-6128 • Ro67-4853 • Ro67-7476 • VU-71; mGlu5-selective: ADX-47273 • CDPPB • CHPG • DFB • VU-1545

Antagonists: Unselective: MCPG • NPS-2390; mGlu1-selective: BAY 36-7620 • CPCCOEt • LY-367,385 • LY-456,236; mGlu5-selective: DMeOB • Fenobam • LY-344,545 • MPEP • MTEP • SIB-1757 • SIB-1893

|

|

|

Group II

|

Agonists: Unselective: CBiPES • DCG-IV • Eglumegad • LY-379,268 • LY-404,039 • LY-487,379 • MGS-0028; mGlu2-selective: BINA • LY-566,332

Antagonists: Unselective: APICA • EGLU • HYDIA • LY-307,452 • LY-341,495 • MCPG: mGlu2-selective: PCCG-4; mGlu3-selective: CECXG

|

|

|

Group III

|

Agonists: Unselective: L-AP4; mGlu4-selective: PHCCC • VU-001,171 • VU-0155,041; mGlu7-selective: AMN082; mGlu8-selective: DCPG

Antagonists: Unselective: CPPG • MAP4 • MSOP • MPPG • MTPG • UBP-1112; mGlu7-selective: MMPIP

|

|

|

Transporter

inhibitors |

|

EAATs

|

DHKA • PDC • WAY-213,613

|

|

|

vGluTs

|

7-CKA • Evans blue

|

|

|

|

Opioids |

|

Opium and

Poppy straw

derivatives |

Crude opiate extracts/

whole opium products |

Compote/Kompot/Polish heroin · Diascordium · B & O Supprettes · Dover's powder · Laudanum · Mithridate · Opium · Paregoric · Poppy straw concentrate · Poppy tea · Smoking opium · Theriac

|

|

| Natural Opiates |

Opium Alkaloids

see also: |

|

|

| Alkaloid Salts Mixtures |

Pantopon · Papaveretum (Omnopon) · Tetrapon

|

|

|

| Semisynthetics |

| Morphine Family |

2-(p-Nitrophenyl)-4-isopropylmorphine · 14-Hydroxymorphine · 14β-Hydroxymorphine · 14β-Hydroxymorphone · 2,4-Dinitrophenylmorphine · 6-Methyldihydromorphine · 6-Methylenedihydrodesoxymorphine · 6-Acetyldihydromorphine/6-Monoacetyldihydromorphine · Acetyldihydromorphine · Azidomorphine · Chlornaltrexamine · Dihydrodesoxymorphine (Desomorphine) · Dihydromorphine · Ethyldihydromorphine · Hydromorphinol · Methyldesorphine · N-Phenethylnormorphine · Pseudomorphine · RAM-378

|

|

| 3,6 Diesters of Morphine |

6-acetyl-1-iodocodeine · 6-nicotinoyldihydromorphine · Acetylpropionylmorphine · Acetylbutyrylmorphine · Diacetyldihydromorphine (Dihydroheroin) · Diacetyldibenzoylmorphine · Dibutyrylcodeine · Dibutyrylmorphine · Dibenzoylmorphine · Diformylmorphine · Dipropanoylmorphine · Heroin (Diacetylmorphine) · Nicomorphine · Tetrabenzoylmorphine · Tetrabutyrylmorphine

|

|

| Codeine-Dionine Family |

14-Hydroxydihydrocodeine · Acetylcodeine · Benzylmorphine · Codeine methylbromide · Desocodeine · Dimethylmorphine (Methocodeine) · Dihydroethylmorphine · Methyldihydromorphine (Dihydroheterocodeine) · Ethylmorphine (Dionine) · Heterocodeine · Isocodeine · Isopropylmorphine · Morpholinylethylmorphine (Pholcodine) · Myrophine · Nalodeine · Transisocodeine

|

|

| Morphinones & Morphols |

1-Bromohydrocodone · 1-Bromooxycodone · 1-Chlorohydrocodone · 1-Chlorooxycodone · 1-Iodohydrocodone · 1-Iodooxycodone · 14-Cinnamoyloxycodeinone · 14-Ethoxymetopon · 14-Methoxymetopon · 14β-Hydroxymorphone · 14-O-Methyloxymorphone · 14-Phenylpropoxymetopon · 7-Spiroindanyloxymorphone · 8,14-Dihydroxydihydromorphinone · Acetylcodone · Acetylmorphinol · Acetylmorphone · α-hydrocodol · Bromoisopropropyldihydromorphinone · Codeinone · Codorphone · Codol · Codoxime · Thebacon (Acetyldihydrocodeinone / Dihydrocodeinone enol acetate) · Ethyldihydromorphinone · Hydrocodol · Hydrocodone · Hydromorphinone · Hydromorphol · Hydromorphone · Hydroxycodeine · Isopropropyldihydrocodeinone · Isopropropyldihydromorphinone · Methyldihydromorphinone · Metopon · Morphenol · Morphinol · Morphinone · Morphol · N-Phenethyl-14-ethoxymetopon · Oxycodone · Oxymorphol · Oxymorphinol · Oxymorphone · Pentamorphone · Semorphone

|

|

| Morphides |

α-chlorocodide (Alphachlorocodide/Chlorocodide) · α-chloromorphide · 3-Bromomorphide · Bromocodide · Bromomorphide (8-Bromomorphide) · Chlorocodide · Chloromorphide · · Codide · Fluorocodide (8-Fluorocodide) · Fluormorphide · Iodocodide · Iodomorphide (8-Iodomorphide) · Morphide

|

|

| Dihydrocodeine Series |

14-hydroxydihydrocodeine · Acetyldihydrocodeine · Dihydrocodeine · Dihydrodesoxycodeine/Desocodeine · Dihydroisocodeine · Nicocodeine · Nicodicodeine

|

|

| Nitrogen Morphine Derivatives |

1-Nitrocodeine · 2-Nitrocodeine · 1-Nitromorphine · 2-Nitromorphine · Codeine-N-Oxide · Heroin-N-Oxide · Hydromorphone-N-Oxide · Morphine-N-Oxide

|

|

| Hydrazones |

Acetylmorphazone · Hydromorphazone · Morphazone · Oxymorphazone

|

|

| Halogenated Morphine Derivatives |

1-Bromocodeine · 2-Bromocodeine · 1-Bromodiacetylmorphine · 2-Bromodiacetylmorphine · 1-Bromodihydrocodeine · 2-Bromodihydrocodeine · 1-Bromodihydromorphine · 2-Bromodihydromorphine · 1-Bromomorphine · 2-Bromomorphine · 1-Chlorocodeine · 2-Chlorocodeine · 1-Chlorodiacetylmorphine · 2-Chlorodiacetylmorphine · 1-Chlorodihydrocodeine · 2-Chlorodihydrocodeine · 1-Chlorodihydromorphine · 2-Chlorodihydromorphine · 1-Chloromorphine · 2-Chloromorphine · 1-Fluorocodeine · 2-Fluorocodeine · 1-Fluorodiacetylmorphine · 2-Fluorodiacetylmorphine · 1-Fluorodihydrocodeine · 2-Fluorodihydrocodeine · 1-Fluorodihydromorphine · 2-Fluorodihydromorphine · 1-Fluoromorphine · 2-Fluoromorphine · 3-Fluoromorphine · 1-Iodocodeine · 2-Iodocodeine · 1-Iododiacetylmorphine · 2-Iododiacetylmorphine · 1-Iododihydrocodeine · 2-Iododihydrocodeine · 1-Iododihydromorphine · 2-Iododihydromorphine · 1-Iodomorphine · 2-Iodomorphine · Chlorethylmorphine

|

|

| Others |

|

|

|

Active Opiate

Metabolites |

Codeine-N-Oxide (Genocodeine) · Dihydromorphine-6-glucuronide · Hydromorphone-N-Oxide · Heroin-7,8-Oxide · Morphine-6-glucuronide · 6-Acetylmorphine · Morphine-N-Oxide (Genomorphine) · Naltrexol · Norcodeine · Normorphine

|

|

|

| Morphinans |

| Morphinan Series |

4-chlorophenylpyridomorphinan · Cyclorphan · Dextrallorphan · Dimemorfan · Levargorphan · Levallorphan · Levorphanol · Levorphan · Levophenacylmorphan · Levomethorphan · Norlevorphanol · N-Methylmorphinan · Oxilorphan · Phenomorphan · Methorphan / Racemethorphan · Morphanol / Racemorphanol · Ro4-1539 · Stephodeline · Xorphanol

|

|

| Others |

1-Nitroaknadinine · 14-episinomenine · 5,6-Dihydronorsalutaridine · 6-Ketonalbuphine · Aknadinine · Butorphanol · Cephakicine · Cephasamine · Cyprodime · Drotebanol · Fenfangjine G · Nalbuphine · Sinococuline · Sinomenine (Cocculine) · Tannagine

|

|

|

| Benzomorphans |

5,9-DEHB · Alazocine · Anazocine · Bremazocine · Cogazocine · Cyclazocine · Dezocine · Eptazocine · Etazocine · Ethylketocyclazocine · Fluorophen · Ketazocine · Metazocine · Pentazocine · Phenazocine · Quadazocine · Thiazocine · Tonazocine · Volazocine · Zenazocine

|

|

| 4-Phenylpiperidines |

Pethidines

(Meperidines) |

4-Fluoromeperidine · Allylnorpethidine · Anileridine · Benzethidine · Carperidine · Difenoxin · Diphenoxylate · Etoxeridine (Carbetidine) · Furethidine · Hydroxypethidine (Bemidone) · Hydroxymethoxypethidine · Morpheridine · Oxpheneridine (Carbamethidine) · Meperidine-N-Oxide · Pethidine (Meperidine) · Pethidine Intermediate A · Pethidine Intermediate B (Norpethidine) · Pethidine Intermediate C (Pethidinic Acid) · Pheneridine · Phenoperidine · Piminodine · Properidine (Ipropethidine) · Sameridine

|

|

| Prodines |

Allylprodine · Isopromedol · Meprodine (α-meprodine / β-meprodine) · MPPP (Desmethylprodine) · PEPAP · Prodine (α-prodine / β-prodine) · Prosidol · Trimeperidine (Promedol)

|

|

| Ketobemidones |

Acetoxyketobemidone · Droxypropine · Ketobemidone · Methylketobemidone · Propylketobemidone

|

|

| Others |

Alvimopan · Loperamide · Picenadol

|

|

|

Open Chain

Opioids |

| Amidones |

Dextromethadone · Dextroisomethadone · Dipipanone · Hexalgon (Norpipanone) · Isomethadone · Levoisomethadone · Levomethadone · Methadone · Methadone intermediate · Normethadone · Norpipanone · Phenadoxone (Heptazone) · Pipidone

|

|

| Methadols |

Dimepheptanol (Racemethadol) · Levacetylmethadol · Noracetylmethadol

|

|

| Moramides |

Dextromoramide · Levomoramide · Moramide intermediate · Racemoramide

|

|

| Thiambutenes |

Diethylthiambutene · Dimethylthiambutene · Ethylmethylthiambutene · Piperidylthiambutene · Pyrrolidinylthiambutene · Thiambutene · Tipepidine

|

|

| Phenalkoxams |

|

|

| Ampromides |

Diampromide · Phenampromide · Propiram

|

|

| Others |

IC-26 · Isoaminile · Lefetamine · R-4066

|

|

|

| Anilidopiperidines |

3-Allylfentanyl · 3-Methylfentanyl · 3-Methylthiofentanyl · 4-Phenylfentanyl · Alfentanil · α-methylacetylfentanyl · α-methylfentanyl · α-methylthiofentanyl · Benzylfentanyl · β-hydroxyfentanyl · β-hydroxythiofentanyl · β-methylfentanyl · Brifentanil · Carfentanil · Fentanyl · Lofentanil · Mirfentanil · Ocfentanil · Ohmefentanyl · Parafluorofentanyl · Phenaridine · Remifentanil · Sufentanil · Thenylfentanyl · Thiofentanyl · Trefentanil

|

|

Oripavine

derivatives |

6,14-Endoethenotetrahydrooripavine · 7-PET · Acetorphine · Alletorphine · BU-48 · Buprenorphine · Butorphine · Cyprenorphine · Dihydroetorphine · Diprenorphine (M5050) · Etorphine · 18,19-Dehydrobuprenorphine (HS-599) · N-cyclopropylmethyl-noretorphine · Nepenthone · Norbuprenorphine · Thevinone · Thienorphine

|

|

| Phenazepanes |

Ethoheptazine · Meptazinol · Metheptazine · Metethoheptazine · Proheptazine

|

|

| Pirinitramides |

Bezitramide · Piritramide

|

|

| Benzimidazoles |

Clonitazene · Etonitazene · Nitazene

|

|

| Indoles |

18-MC · 7-Acetoxymitragynine · 7-Hydroxymitragynine · Akuammidine · Akuammine · Eseroline · Hodgkinsine · Ibogaine · Mitragynine · Noribogaine · Pericine · ψ-Akuammigine

|

|

| Diphenylmethylpiperazines |

BW373U86 · DPI-221 · DPI-287 · DPI-3290 · SNC-80

|

|

Opioid peptides

see also: The Opioid Peptides |

Adrenorphin · Amidorphin · Casomorphin · DADLE · DALDA · DAMGO · Dermenkephalin · Dermorphin · Deltorphin · DPDPE · Dynorphin · Endomorphin · Endorphin · Enkephalin · Gliadorphin · Morphiceptin · Nociceptin · Octreotide · Opiorphin · Rubiscolin · TRIMU 5

|

|

| Others |

3-(3-Methoxyphenyl)-3-ethoxycarbonyltropane · AH-7921 • Azaprocin · BDPC · Bisnortilidine · BRL-52537 · Bromadoline • C-8813 · Ciramadol · Doxpicomine • Enadoline · Esketamine · Faxeladol · GR-89696 · Herkinorin · ICI-199,441 · ICI-204,448 · J-113,397 · JTC-801 · Ketamine · LPK-26 · Methopholine · Methoxetamine · N-Desmethylclozapine · NNC 63-0532 · Nortilidine · O-Desmethyltramadol · Phenadone · Phencyclidine · Prodilidine · Profadol · Ro64-6198 · Salvinorin A · SB-612,111 · SC-17599 · RWJ-394,674 · TAN-67 · Tapentadol · Tecodine · Tifluadom · Tilidine · Tramadol · Trimebutine · U-50,488 · U-69,593 · Viminol · W-18 ·

|

|

Opioid Antagonists

&

Inverse-Agonists |

5'-Guanidinonaltrindole · β-Funaltrexamine · 6β-Naltrexol · Alvimopan · Amiphenazole · Binaltorphimine · Chlornaltrexamine · Clocinnamox · Cyclazocine · Cyprodime · Diprenorphine (M5050) · Fedotozine · JDTic · Levallorphan · Methocinnamox · Methylnaltrexone · Nalfurafine · Nalmefene · Nalmexone · Naloxazone · Naloxonazine · Naloxone · Naloxone benzoylhydrazone · Nalorphine · Naltrexone · Naltriben · Naltrindole · Norbinaltorphimine · Oxilorphan · S-allyl-3-hydroxy-17-thioniamorphinan (SAHTM)

|

|