Permittivity

In electromagnetism, permittivity is the measure of how much resistance is encountered when forming an electric field in a vacuum. In other words, permittivity is a measure of how an electric field affects, and is affected by, a dielectric medium. Permittivity is determined by the ability of a material to polarize in response to the field, and thereby reduce the total electric field inside the material. Thus, permittivity relates to a material's ability to transmit (or "permit") an electric field.

It is directly related to electric susceptibility, which is a measure of how easily a dielectric polarizes in response to an electric field.

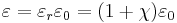

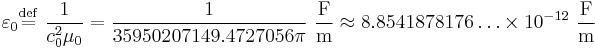

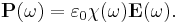

In SI units, permittivity ε is measured in farads per meter (F/m); electric susceptibility χ is dimensionless. They are related to each other through

where εr is the relative permittivity of the material, and  = 8.85… × 10−12 F/m is the vacuum permittivity.

= 8.85… × 10−12 F/m is the vacuum permittivity.

Contents |

Explanation

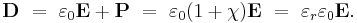

In electromagnetism, the electric displacement field D represents how an electric field E influences the organization of electrical charges in a given medium, including charge migration and electric dipole reorientation. Its relation to permittivity in the very simple case of linear, homogeneous, isotropic materials with "instantaneous" response to changes in electric field is

where the permittivity ε is a scalar. If the medium is anisotropic, the permittivity is a second rank tensor.

In general, permittivity is not a constant, as it can vary with the position in the medium, the frequency of the field applied, humidity, temperature, and other parameters. In a nonlinear medium, the permittivity can depend on the strength of the electric field. Permittivity as a function of frequency can take on real or complex values.

In SI units, permittivity is measured in farads per meter (F/m or A2·s4·kg−1·m−3). The displacement field D is measured in units of coulombs per square meter (C/m2), while the electric field E is measured in volts per meter (V/m). D and E describe the interaction between charged objects. D is related to the charge densities associated with this interaction, while E is related to the forces and potential differences.

Vacuum permittivity

The vacuum permittivity ε0 (also called permittivity of free space or the electric constant) is the ratio D/E in free space. It also appears in the Coulomb force constant 1/4πε0.

Its value is[1]

where

- c0 is the speed of light in free space,[2]

- µ0 is the vacuum permeability.

Constants c0 and μ0 are defined in SI units to have exact numerical values, shifting responsibility of experiment to the determination of the meter and the ampere.[3] (The approximation in the second value of ε0 above stems from π being an irrational number.)

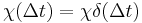

Relative permittivity

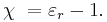

The linear permittivity of a homogeneous material is usually given relative to that of free space, as a relative permittivity εr (also called dielectric constant, although this sometimes only refers to the static, zero-frequency relative permittivity). In an anisotropic material, the relative permittivity may be a tensor, causing birefringence. The actual permittivity is then calculated by multiplying the relative permittivity by ε0:

where

- χ (frequently written χe) is the electric susceptibility of the material.

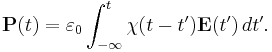

The susceptibility is defined as the constant of proportionality (which may be a tensor) relating an electric field E to the induced dielectric polarization density P such that

where  is the electric permittivity of free space.

is the electric permittivity of free space.

The susceptibility of a medium is related to its relative permittivity  by

by

So in the case of a vacuum,

The susceptibility is also related to the polarizability of individual particles in the medium by the Clausius-Mossotti relation.

The electric displacement D is related to the polarization density P by

The permittivity ε and permeability µ of a medium together determine the phase velocity c of electromagnetic radiation through that medium:

Dispersion and causality

In general, a material cannot polarize instantaneously in response to an applied field, and so the more general formulation as a function of time is

That is, the polarization is a convolution of the electric field at previous times with time-dependent susceptibility given by  . The upper limit of this integral can be extended to infinity as well if one defines

. The upper limit of this integral can be extended to infinity as well if one defines  for

for  . An instantaneous response corresponds to Dirac delta function susceptibility

. An instantaneous response corresponds to Dirac delta function susceptibility  .

.

It is more convenient in a linear system to take the Fourier transform and write this relationship as a function of frequency. Due to the convolution theorem, the integral becomes a simple product,

This frequency dependence of the susceptibility leads to frequency dependence of the permittivity. The shape of the susceptibility with respect to frequency characterizes the dispersion properties of the material.

Moreover, the fact that the polarization can only depend on the electric field at previous times (i.e.  for

for  ), a consequence of causality, imposes Kramers–Kronig constraints on the susceptibility

), a consequence of causality, imposes Kramers–Kronig constraints on the susceptibility  .

.

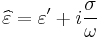

Complex permittivity

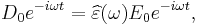

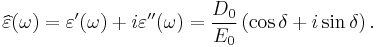

As opposed to the response of a vacuum, the response of normal materials to external fields generally depends on the frequency of the field. This frequency dependence reflects the fact that a material's polarization does not respond instantaneously to an applied field. The response must always be causal (arising after the applied field) which can be represented by a phase difference. For this reason permittivity is often treated as a complex function (since complex numbers allow specification of magnitude and phase) of the (angular) frequency of the applied field ω,  . The definition of permittivity therefore becomes

. The definition of permittivity therefore becomes

where

- D0 and E0 are the amplitudes of the displacement and electrical fields, respectively,

- i is the imaginary unit, i 2 = −1.

It is important to realize that the choice of sign for time-dependence dictates the sign convention for the imaginary part of permittivity. The signs used here correspond to those commonly used in physics, whereas for the engineering convention one should reverse all imaginary quantities.

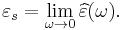

The response of a medium to static electric fields is described by the low-frequency limit of permittivity, also called the static permittivity εs (also εDC ):

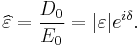

At the high-frequency limit, the complex permittivity is commonly referred to as ε∞. At the plasma frequency and above, dielectrics behave as ideal metals, with electron gas behavior. The static permittivity is a good approximation for altering fields of low frequencies, and as the frequency increases a measurable phase difference δ emerges between D and E. The frequency at which the phase shift becomes noticeable depends on temperature and the details of the medium. For moderate fields strength (E0), D and E remain proportional, and

Since the response of materials to alternating fields is characterized by a complex permittivity, it is natural to separate its real and imaginary parts, which is done by convention in the following way:

where

- ε" is the imaginary part of the permittivity, which is related to the dissipation (or loss) of energy within the medium.

- ε' is the real part of the permittivity, which is related to the stored energy within the medium.

The complex permittivity is usually a complicated function of frequency ω, since it is a superimposed description of dispersion phenomena occurring at multiple frequencies. The dielectric function ε(ω) must have poles only for frequencies with positive imaginary parts, and therefore satisfies the Kramers–Kronig relations. However, in the narrow frequency ranges that are often studied in practice, the permittivity can be approximated as frequency-independent or by model functions.

At a given frequency, the imaginary part of  leads to absorption loss if it is positive (in the above sign convention) and gain if it is negative. More generally, the imaginary parts of the eigenvalues of the anisotropic dielectric tensor should be considered.

leads to absorption loss if it is positive (in the above sign convention) and gain if it is negative. More generally, the imaginary parts of the eigenvalues of the anisotropic dielectric tensor should be considered.

In the case of solids, the complex dielectric function is intimately connected to band structure. The primary quantity that characterizes the electronic structure of any crystalline material is the probability of photon absorption, which is directly related to the imaginary part of the optical dielectric function ε(ω). The optical dielectric function is given by the fundamental expression:[5]

In this expression, Wcv(E) represents the product of the Brillouin zone-averaged transition probability at the energy E with the joint density of states,[6][7] Jcv(E); φ is a broadening function, representing the role of scattering in smearing out the energy levels.[8] In general, the broadening is intermediate between Lorentzian and Gaussian;[9][10] for an alloy it is somewhat closer to Gaussian because of strong scattering from statistical fluctuations in the local composition on a nanometer scale.

Classification of materials

Materials can be classified according to their permittivity and conductivity, σ. Materials with a large amount of loss inhibit the propagation of electromagnetic waves. In this case, generally when σ/(ωε) >> 1, we consider the material to be a good conductor. Dielectrics are associated with lossless or low-loss materials, where σ/(ωε) << 1. Those that do not fall under either limit are considered to be general media. A perfect dielectric is a material that has no conductivity, thus exhibiting only a displacement current. Therefore it stores and returns electrical energy as if it were an ideal capacitor.

Lossy medium

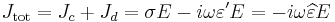

In the case of lossy medium, i.e. when the conduction current is not negligible, the total current density flowing is:

where

- σ is the conductivity of the medium;

- ε' is the real part of the permittivity.

is the complex permittivity

is the complex permittivity

The size of the displacement current is dependent on the frequency ω of the applied field E; there is no displacement current in a constant field.

In this formalism, the complex permittivity is defined as[11]:

In general, the absorption of electromagnetic energy by dielectrics is covered by a few different mechanisms that influence the shape of the permittivity as a function of frequency:

- First, are the relaxation effects associated with permanent and induced molecular dipoles. At low frequencies the field changes slowly enough to allow dipoles to reach equilibrium before the field has measurably changed. For frequencies at which dipole orientations cannot follow the applied field due to the viscosity of the medium, absorption of the field's energy leads to energy dissipation. The mechanism of dipoles relaxing is called dielectric relaxation and for ideal dipoles is described by classic Debye relaxation.

- Second are the resonance effects, which arise from the rotations or vibrations of atoms, ions, or electrons. These processes are observed in the neighborhood of their characteristic absorption frequencies.

The above effects often combine to cause non-linear effects within capacitors. For example, dielectric absorption refers to the inability of a capacitor that has been charged for a long time to completely discharge when briefly discharged. Although an ideal capacitor would remain at zero volts after being discharged, real capacitors will develop a small voltage, a phenomenon that is also called soakage or battery action. For some dielectrics, such as many polymer films, the resulting voltage may be less than 1-2% of the original voltage. However, it can be as much as 15 - 25% in the case of electrolytic capacitors or supercapacitors.

Quantum-mechanical interpretation

In terms of quantum mechanics, permittivity is explained by atomic and molecular interactions.

At low frequencies, molecules in polar dielectrics are polarized by an applied electric field, which induces periodic rotations. For example, at the microwave frequency, the microwave field causes the periodic rotation of water molecules, sufficient to break hydrogen bonds. The field does work against the bonds and the energy is absorbed by the material as heat. This is why microwave ovens work very well for materials containing water. There are two maxima of the imaginary component (the absorptive index) of water, one at the microwave frequency, and the other at far ultraviolet (UV) frequency. Both of these resonances are at higher frequencies than the operating frequency of microwave ovens.

At moderate frequencies, the energy is too high to cause rotation, yet too low to affect electrons directly, and is absorbed in the form of resonant molecular vibrations. In water, this is where the absorptive index starts to drop sharply, and the minimum of the imaginary permittivity is at the frequency of blue light (optical regime). This is why sunlight does not damage water-containing organs such as the eye.[12]

At high frequencies (such as UV and above), molecules cannot relax, and the energy is purely absorbed by atoms, exciting electron energy levels. Thus, these frequencies are classified as ionizing radiation.

While carrying out a complete ab initio (that is, first-principles) modelling is now computationally possible, it has not been widely applied yet. Thus, a phenomenological model is accepted as being an adequate method of capturing experimental behaviors. The Debye model and the Lorentz model use a 1st-order and 2nd-order (respectively) lumped system parameter linear representation (such as an RC and an LRC resonant circuit).

Measurement

The dielectric constant of a material can be found by a variety of static electrical measurements. The complex permittivity is evaluated over a wide range of frequencies by using different variants of dielectric spectroscopy, covering nearly 21 orders of magnitude from 10−6 to 1015 Hz. Also, by using cryostats and ovens, the dielectric properties of a medium can be characterized over an array of temperatures. In order to study systems for such diverse exciting fields, a number of measurement setups are used, each adequate for a special frequency range.

Various microwave measurement techniques are outlined in Chen et al..[13] Typical errors for the Hakki-Coleman method employing a puck of material between conducting planes are about 0.3%.[14]

- Low-frequency time domain measurements (10−6-103 Hz)

- Low-frequency frequency domain measurements (10−5-106 Hz)

- Reflective coaxial methods (106-1010 Hz)

- Transmission coaxial method (108-1011 Hz)

- Quasi-optical methods (109-1010 Hz)

- Fourier-transform methods (1011-1015 Hz)

At infrared and optical frequencies, a common technique is ellipsometry. Dual polarisation interferometry is also used to measure the complex refractive index for very thin films at optical frequencies.

See also

- Density functional theory

- Electric field screening

- Green-Kubo relations

- Green's function (many-body theory)

- Linear response function

- Rotational Brownian motion

- Electromagnetic Permeability

References

- ↑ electric constant

- ↑ Current practice of standards organizations such as NIST and BIPM is to use c0, rather than c, to denote the speed of light in vacuum according to ISO 31. In the original Recommendation of 1983, the symbol c was used for this purpose. See NIST Special Publication 330, Appendix 2, p. 45 .

- ↑ Latest (2006) values of the constants (NIST)

- ↑ Dielectric Spectroscopy

- ↑ Peter Y. Yu, Manuel Cardona (2001). Fundamentals of Semiconductors: Physics and Materials Properties. Berlin: Springer. p. 261. ISBN 3540254706. http://books.google.com/?id=W9pdJZoAeyEC&pg=PA261.

- ↑ José García Solé, Jose Solé, Luisa Bausa, (2001). An introduction to the optical spectroscopy of inorganic solids. Wiley. Appendix A1, pp, 263. ISBN 0470868856. http://books.google.com/?id=c6pkqC50QMgC&pg=PA263.

- ↑ John H. Moore, Nicholas D. Spencer (2001). Encyclopedia of chemical physics and physical chemistry. Taylor and Francis. p. 105. ISBN 0750307986. http://books.google.com/?id=Pn2edky6uJ8C&pg=PA108.

- ↑ Solé, José García; Bausá, Louisa E; Jaque, Daniel (2005-03-22). Solé and Bausa. p. 10. ISBN 3540254706. http://books.google.com/?id=c6pkqC50QMgC&pg=PA10.

- ↑ Hartmut Haug, Stephan W. Koch (1994). Quantum Theory of the Optical and Electronic Properties of Semiconductors. World Scientific. p. 196. ISBN 9810218648. http://books.google.com/?id=Ab2WnFyGwhcC&pg=PA196.

- ↑ Manijeh Razeghi (2006). Fundamentals of Solid State Engineering. Birkhauser. p. 383. ISBN 0387281525. http://books.google.com/?id=6x07E9PSzr8C&pg=PA383.

- ↑ John S. Seybold (2005) Introduction to RF propagation. 330 pp, eq.(2.6), p.22.

- ↑ Braun, Charles L.; Smirnov, Sergei N. (1993). "Why is water blue?". Journal of Chemical Education 70 (8): 612. doi:10.1021/ed070p612. http://www.dartmouth.edu/~etrnsfer/water.htm.

- ↑ Linfeng Chen, V. V. Varadan, C. K. Ong, Chye Poh Neo (2004). "Microwave theory and techniques for materials characterization". Microwave electronics. Wiley. p. 37. ISBN 0470844922. http://books.google.com/?id=2oA3po4coUoC&pg=PA37.

- ↑ Mailadil T. Sebastian (2008). Dielectric Materials for Wireless Communication. Elsevier. p. 19. ISBN 0080453309. http://books.google.com/?id=eShDR4_YyM8C&pg=PA19.

Further reading

- Theory of Electric Polarization: Dielectric Polarization, C.J.F. Böttcher, ISBN 0-444-41579-3

- Dielectrics and Waves edited by A. von Hippel, Arthur R., ISBN 0-89006-803-8

- Dielectric Materials and Applications edited by Arthur von Hippel, ISBN 0-89006-805-4.

External links

- Electromagnetism, a chapter from an online textbook

![\varepsilon(\omega)=1+\frac{8\pi^2e^2}{m^2}\sum_{c,v}\int W_{cv}(E) \left[ \varphi (\hbar \omega - E)-\varphi( \hbar \omega +E) \right ] \, dx.](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/e2131935b920e0652da4bbbc05a290ad.png)