Pelican

| Pelican Fossil range: Oligocene-Recent, 30–0 Ma |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Australian Pelican (Pelecanus conspicillatus) Pelican chick |

|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Pelecaniformes |

| Family: | Pelecanidae Rafinesque, 1815 |

| Genus: | Pelecanus Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Species | |

|

|

A pelican, derived from the Greek word pelekys (meaning “ax” and applied to birds that cut wood with their bills or beaks), is a large water bird with a large throat pouch, belonging to the bird family Pelecanidae.

Along with the darters, cormorants, gannets, boobies, frigatebirds, and tropicbirds, pelicans make up the order Pelecaniformes. Modern pelicans, of which there are eight species, are found on all continents except Antarctica. They primarily inhabit warm regions, though breeding ranges reach 45° south (Australian Pelican, P. conspicillatus) and 60° North (American White Pelicans, P. erythrorhynchos, in western Canada).[1] Birds of inland and coastal waters, they are absent from polar regions, the deep ocean, oceanic islands, and inland South America.

Contents |

Description

Pelicans are large birds with large pouched bills. The smallest is the Brown Pelican (P. occidentalis), small individuals of which can be as little as 2.75 kg (6 lb), 106 cm (42 in) long and can have a wingspan of as little as 1.83 m (6 ft). The largest is believed to be the Dalmatian Pelican (P. crispus), at up to 15 kg (33 lb), 183 cm (72 in) long, with a maximum wingspan of 3 metres [nearly 10 foot]. The Australian Pelican has the longest bill of any bird[1].

Pelicans swim well with their short, strong legs and their feet with all four toes webbed (as in all birds placed in the order Pelecaniformes). The tail is short and square, with 20 to 24 feathers. The wings are long and have the unusually large number of 30 to 35 secondary flight feathers. A layer of special fibers deep in the breast muscles can hold the wings rigidly horizontal for gliding and soaring. Thus they can exploit thermals to commute over 150 km (100 miles) to feeding areas.[1]

Pelicans rub the backs of their heads on their preen glands to pick up its oily secretion, which they transfer to their plumage to waterproof it.[1]

Sub-groups

The pelicans can be divided into two groups: those with mostly white adult plumage, which nest on the ground (Australian, Dalmatian, Great White, and American White Pelicans), and those with gray or brown plumage, which nest in trees (Pink-backed, Spot-billed, and Brown, plus the Peruvian Pelican, which nests on sea rocks). The Peruvian Pelican is sometimes considered conspecific with the Brown Pelican.[1]

Feeding

The diet of a Pelican usually consists of fish, but they also eat amphibians, crustaceans and on some occasions, smaller birds.[2][3] They often catch fish by expanding the throat pouch. Then they must drain the pouch above the surface before they can swallow. This operation takes up to a minute, during which time other seabirds are particularly likely to steal the fish. Pelicans in their turn sometimes pirate prey from other seabirds.[1]

The white pelicans often fish in groups. They will form a line to chase schools of small fish into shallow water, and then scoop them up. Large fish are caught with the bill-tip, then tossed up in the air to be caught and slid into the gullet head first.

The Brown Pelican of North America usually plunge-dives for its prey. Rarely, other species such as the Peruvian Pelican and the Australian Pelican practice this method.

A pelican in St. James's Park in London was once filmed eating a fully grown pigeon alive.[2][3]

Reproduction

Pelicans are gregarious and nest colonially. The ground-nesting (white) species have a complex communal courtship involving a group of males chasing a single female in the air, on land, or in the water while pointing, gaping, and thrusting their bills at each other. They can finish the process in a day. The tree-nesting species have a simpler process in which perched males advertise for females.[1]

In all species copulation begins shortly after pairing and continues for 3 to 10 days before egg-laying. The male brings the nesting material, ground-nesters (which may not build a nest) sometimes in the pouch and tree-nesters crosswise in the bill. The female then heaps the material up to form a simple structure.[1]

Both sexes incubate with the eggs on top of or below the feet. They may display when changing shifts. All species lay at least two eggs, and hatching success for undisturbed pairs can be as high as 95 percent, but because of competition between siblings or outright siblicide, usually all but one nestling dies within the first few weeks (or later in the Pink-backed and Spot-billed species). The young are fed copiously. Before or especially after being fed, they may seem to have a seizure that ends in falling unconscious; the reason is not clearly known.[1]

Parents of ground-nesting species have another strange behavior: they sometimes drag older young around roughly by the head before feeding them. The young of these species gather in "pods" or "crèches" of up to 100 birds in which parents recognize and feed only their own offspring. By 6 to 8 weeks they wander around, occasionally swimming, and may practice communal feeding.[1]

Young of all species fledge 10 to 12 weeks after hatching. They may remain with their parents afterwards, but are now seldom or never fed. Overall breeding success is highly inconsistent.[1]

Pairs are monogamous for a single season, but the pair bond extends only to the nesting area; mates are independent away from the nest.

Populations

The Dalmatian Pelican and the Spot-billed Pelican are the rarest species, with the population of the former estimated at between 10,000 and 20,000[4] and that of the latter at 13,000 to 18,000.[5] The most common is believed to be the Australian Pelican, with a population generally estimated at around 400,000 individuals. However, estimates for the species have varied wildly between 100,000 and 1,000,000 over the years, and it is possible that the White Pelican, the population of which is more consistently estimated at 270,000 and 290,000 individuals, is in fact the more common species. The brown pelican may be even more numerous with estimates of 650,000 birds throughout its range. It has been removed from the endangered species list.[6]

Species

Brown Pelican |

Peruvian Pelican |

American White Pelican |

Great White Pelican |

Dalmatian Pelican |

Pink-backed Pelican |

Spot-billed Pelican |

Australian Pelican |

From the fossil record it is known that pelicans have been around for over 30 million years, the earliest fossil Pelecanus being found in Oligocene deposits in France.[7] A prehistoric genus has been named Miopelecanus, while Protopelicanus may be a pelicanid or pelecaniform – or a similar aquatic bird such as a pseudotooth bird (Pelagornithidae). The supposed Miocene pelican Liptornis from Argentina is a nomen dubium, being based on hitherto indeterminable fragments.

A number of fossil species are also known from the extant genus Pelecanus:

- Pelecanus halieus (Late Pliocene of Idaho, USA)

- Pelecanus cadimurka

- Pelecanus cauleyi

- Pelecanus gracilis

- Pelecanus halieus

- Pelecanus intermedius

- Pelecanus lazerus

- Pelecanus odessanus

- Pelecanus schreiberi

- Pelecanus sivalensis

- Pelecanus tirarensis

Symbolism and popular culture

In medieval Europe, the pelican was thought to be particularly attentive to her young, to the point of providing her own blood when no other food was available. As a result, the pelican became a symbol of the Passion of Jesus and of the Eucharist (see for example the hymn "Adoro te devote", or "Humbly We Adore Thee", by Saint Thomas Aquinas, where in the second to last verse he makes reference to Christ, the loving divine pelican). It also became a symbol in bestiaries for self-sacrifice, and was used in heraldry ("a pelican in her piety" or "a pelican vulning (wounding) herself"). Another version of this is that the pelican used to kill its young and then resurrect them with its blood, this being analogous to the sacrifice of Jesus. Thus the symbol of the Irish Blood Transfusion Service (IBTS) is a pelican, and for most of its existence the headquarters of the service was located at Pelican House in Dublin, Ireland.

The emblems of both Corpus Christi College, Cambridge and Corpus Christi College, Oxford are pelicans, showing its use as a medieval Christian symbol ('Corpus Christi' means 'body of Christ').

Likewise a folktale from India says that a pelican killed her young by rough treatment but was then so contrite that she resurrected them with her own blood.[1]

These legends may have arisen because pelicans look as if they are stabbing themselves as they often press their bill into their chest to fully empty their pouch. Other possibilities are that they often rest their bills on their breasts, and that the Dalmatian Pelican has a blood-red pouch in the early breeding season.[1]

The symbol is used today on the Louisiana state flag and Louisiana state seal, as the Brown pelican is the Louisiana state bird. The pelican is featured prominently on the seal of Louisiana State University. A pelican logo is used by the Portuguese bank Montepio Geral.[2]

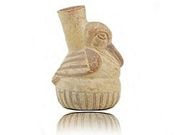

The Moche people of ancient Peru worshipped nature.[8] They placed emphasis on animals and often depicted pelicans in their art.[9]

A pelican is depicted on the reverse of the Albanian 1 lek coin, issued in 1996.[10]

The pelican has also been the subject of a poem by John Bennet and subsequent song—The Pelican—by Richard Proulx, composed in 1995. The song was dedicated to the Cathedral Choir of the Cathedral of the Madeleine, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Several news magazines such as Time and the Economist, and environmental groups, have used the oil-drenched pelican as a symbol of the environmental impact of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

In the 2003 Pixar animated film Finding Nemo, a Brown Pelican named Nigel helps Marlin find his son.

In the Halo series, the UNSC uses a drop ship named the Pelican.

Exceptional behaviors

25 October 2006, a pelican swallowed a living pigeon in St. James Park, London. According to tourists watching it, the pelican walked to the pigeon and grabbed it in its beak, hence starting the 20 minute struggle which ended when the victim was swallowed "head first down while flapping all the way down"[11]. This behavior has been filmed on separate occasions in Saint James Park and also in a zoo in Ukraine [12][13]

On the 11 May 2008, Debbie Shoemaker needed 20 stitches after a pelican rammed into her face and died, believed to be diving for fish in the sea off Florida[14].

In the Zoo Basel, a Great White Pelican named Killer Jonny hunts and eats any duck (or other smaller bird) that enters the pelican exhibit. Today, there are rarely any ducks on the pelican lake, while on all other bodies of water they are seen in normal numbers.

On the island of Malgas in South Africa, the biologist Marta de Ponte was the first to discover Great White Pelicans eating Cape Gannet chicks[15]. The pelicans were then captured on film exhibiting this behaviour in the BBC documentary Life (BBC TV series). The same breed of pelican has been observed swallowing Cape cormorants, kelp gulls, swift terns and African penguins.

Environmental damage

The Pelican environment suffered significant ecosystem damage from the 2010 Gulf of Mexico petroleum disaster. Dead pelicans were seen on Raccoon Island, the largest pelican rookery in Louisiana. Rebuilt after Hurricane Katrina, it was home to more than 60,000 pelicans, but since the oil spill mature pelicans are scarce. Instead, there are thousands of dead birds and emaciated and abandoned juvenile and baby birds.[16]

Gallery

Pelicans often travel in groups |

Relief of a "pelican in her piety" |

An Australian Pelican coming out of water |

A Brown Pelican in flight |

Brown Pelican flock over Havana Bay |

Brown Pelicans, Melbourne, Florida, USA. |

Pelicans in the Danube Delta. |

Eastern White Pelican, Blackpool Zoo. |

.jpg) Pink-backed Pelican, San Diego Wild Animal Park |

Immature Brown pelicans on the beach at Playa del Carmen, Mexico |

White pelican, Lovech Zoo. |

Pelican in Los Angeles, California |

Brown pelican with fishing line stuck in beak, Long Beach, CA |

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 Nelson, J. Bryan; Schreiber, Elizabeth Anne; Schreiber, Ralph W. (2003). "Pelicans". In Christopher Perrins (Ed.). Firefly Encyclopedia of Birds. Firefly Books. pp. 78–81. ISBN 1-55297-777-3.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Pelican swallows pigeon in park". BBC News. 25 October 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/london/6083468.stm. Retrieved 2006-10-25.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Pelican's pigeon meal not so rare". BBC News. 30 October 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/london/6098678.stm. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ↑ BirdLife International (2006). Pelecanus crispus. 2006. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN 2006. www.iucnredlist.org. Retrieved on 11 May 2006.

- ↑ BirdLife International (2004). Pelecanus philippensis. 2006. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN 2006. www.iucnredlist.org. Retrieved on 10 May 2006.

- ↑ San Francisco Chronicle, http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2009/11/12/BAP71AIOJD.DTL, 12 November 2009. Retrieved 12 November 2009

- ↑ Louchart, A., Tourment, N. and Carrier, C. (2010). "The earliest known pelican reveals 30 million years of evolutionary stasis in beak morphology." Journal of Ornithology,

- ↑ Benson, Elizabeth, The Mochica: A Culture of Peru. New York, NY: Praeger Press. 1972

- ↑ Berrin, Katherine & Larco Museum. The Spirit of Ancient Peru:Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1997.

- ↑ Bank of Albania. Currency: Albanian coins in circulation, issue of 1995, 1996 and 2000. – Retrieved on 23 March 2009.

- ↑ "Pelican swallows pigeon in park". BBC. 2006-10-25. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/england/london/6083468.stm. Retrieved 2009-01-26.

- ↑ [1], Pelican eats a dove in Ukraine

- ↑ [url=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=je9NARZJJwg&feature=related],Pelican eats a dove in Saint James Park

- ↑ "Pelican 'bombs' bather in Florida". BBC. 2008-05-11. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/7394384.stm. Retrieved 2009-01-26.

- ↑ "Pelicans filmed gobbling gannets". BBC. 2009-11-05. http://news.bbc.co.uk/earth/hi/earth_news/newsid_8343000/8343195.stm. Retrieved 2009-11-05.

- ↑ "Grim inventory of wildlife claimed by Gulf spill" July 15, 2010. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/38262136/ns/us_news-environment

External links

- The Symbolism of the Pelican article in the Arlington Catholic Herald.

- Pelican videos on the Internet Bird Collection

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||