Euphorbia

| Euphorbia | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Euphorbia cf. serrata | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Rosids |

| Order: | Malpighiales |

| Family: | Euphorbiaceae |

| Subfamily: | Euphorbioideae |

| Tribe: | Euphorbieae |

| Subtribe: | Euphorbiinae |

| Genus: | Euphorbia L. |

| Type species | |

| Euphorbia antiquorum

Euphorbia serrata |

|

| Subgenera | |

|

Chamaesyce |

|

| Diversity | |

| c.2160 species | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Chamaesyce |

|

Euphorbia is a genus of plants belonging to the family Euphorbiaceae. Consisting of about 2160 species, Euphorbia is one of the most diverse genera in the plant kingdom, maybe exceeded only by Senecio . Members of the family and genus are sometimes referred to as Spurges. Euphorbia antiquorum and Euphorbia serrata are the type species for the genus Euphorbia, it was described by Linnaeus in 1753 in Species Plantarum. The genus is primarily found in the tropical and subtropical regions of Africa and the Americas, but also in temperate zones worldwide. Succulent species originate mostly from Africa, the Americas and Madagascar. There exists a wide range of insular species: on the Hawaiian Islands where spurges are collectively known as "akoko",[1] and on the Canary Islands as "tabaibas".[2][3]

The common name "spurge" derives from the Middle English/Old French espurge ("to purge"), due to the use of the plant's sap as a purgative.

The botanical name Euphorbia derives from Euphorbus, the Greek physician of king Juba II of Numidia (52-50 BC–23 AD). He is reported to have used a certain plant, possibly Resin Spurge (E. resinifera), as a herbal remedy when the king suffered from a swollen belly. Carolus Linnaeus assigned the name Euphorbia to the entire genus in the physician's honor.[4]

Juba II himself was a noted patron of the arts and sciences and sponsored several expeditions and biological research. He also was a notable author, writing several scholarly and popular scientific works such as treatises on natural history or a best-selling traveller's guide to Arabia. Euphorbia regisjubae (King Juba's Euphorbia) was named to honor the king's contributions to natural history and his role in bringing the genus to notice.

Contents |

Description

The plants are annual or perennial herbs, woody shrubs or trees with a caustic, poisonous milky sap (latex). The roots are fine or thick and fleshy or tuberous. Many species are more or less succulent, thorny or unarmed. The main stem and mostly also the side arms of the succulent species are thick and fleshy, 15–91 cm (6–36 inches) tall. The deciduous leaves are opposite, alternate or in whorls. In succulent species the leaves are mostly small and short-lived. The stipules are mostly small, partly transformed into spines or glands, or missing.

Like all members of the family Euphorbiaceae, all spurges have unisexual flowers. In Euphorbia these are greatly reduced and grouped into pseudanthia called cyathia. The majority of species are monoecious (bearing male and female flowers on the same plant), although some are dioecious with male and female flowers occurring on different plants. It is not unusual for the central cyathia of a cyme to be purely male, and for lateral cyathia to carry both sexes. Sometimes young plants or those growing under unfavourable conditions are male only, and only produce female flowers in the cyathia with maturity or as growing conditions improve. The bracts are often leaf-like, sometimes brightly coloured and attractive, sometimes reduced to tiny scales. The fruits are three (rarely two) compartment capsules, sometimes fleshy but almost always ripening to a woody container that then splits open (explosively, see explosive dehiscence). The seeds are 4-angled, oval or spherical, and in some species have a caruncle.

Xerophytes and succulents

In the genus Euphorbia, succulence in the species has often evolved divergently and to differing degrees. Sometimes it is difficult to decide, and it is a question of interpretation, whether or not a species is really succulent or "only" xerophytic. In some cases, especially with geophytes, plants closely related to the succulents are normal herbs. About 850 species are succulent in the strictest sense. If one includes slightly succulent and xerophytic species, this figure rises to about 1000, representing about 45% of all Euphorbia species.

Toxicity

The latex (milky sap) of spurges acts as a deterrent for herbivores as well as a wound healer. Usually it is white, but in rare cases (e.g. E. abdelkuri) yellow. As it is under pressure, it runs out from the slightest wound and congeals within a few minutes of contact with the air. Among the component parts are many di- or tri-terpen esters, which can vary in composition according to species, and in some cases the variant may be typical of that species. The terpen ester composition determines how caustic and irritating to the skin it is. In contact with mucous membranes (eyes, nose, mouth) the latex can produce extremely painful inflammation. In experiments with animals it was found that the terpen ester resiniferatoxin had an irritating effect 10,000 to 100,000 times stronger than capsaicin, the "hot" substance found in chili peppers. Several terpen esters are also known to be carcinogenic.

Therefore spurges should be handled with caution. Latex coming in contact with the skin should be washed off immediately and thoroughly. Partially or completely congealed latex is often no longer soluble in water, but can be removed with an emulsion (milk, hand-cream). A physician should be consulted regarding any inflammation of a mucous membrane, especially the eyes, as severe eye damage including possible permanent blindness may result from acute exposure to the sap.[5] It has been noticed, when cutting large succulent spurges in a greenhouse, that vapours from the latex spread and can cause severe irritation to the eyes and air passages several metres away. Precautions, including sufficient ventilation, are required. Small children and domestic pets should be kept from contact with spurges.

Uses

Several spurges are grown as garden plants, among them Poinsettia (E. pulcherrima) and the succulent E. trigona. E. pekinensis (Chinese: 大戟; pinyin: dàjǐ) is used in traditional Chinese medicine, where it is regarded as one of the 50 fundamental herbs. Several Euphorbia species are used as food plants by the larvae of some Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths), like the Spurge Hawk-moths (Hyles euphorbiae and Hyles tithymali), as well as the Giant Leopard Moth.

Systematics and taxonomy

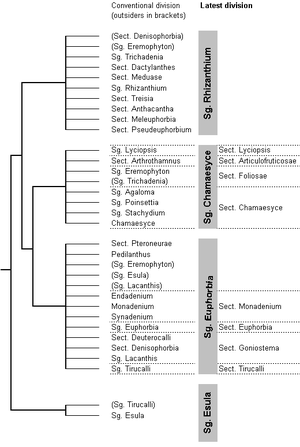

According to recent studies of DNA sequence data[6] most of the smaller "satellite genera" around the huge genus Euphorbia nest deep within the latter. Consequently these taxa, namely the never generally accepted genus Chamaesyce as well as the smaller genera Cubanthus,[7] Elaeophorbia, Endadenium, Monadenium, Synadenium and Pedilanthus were transferred to Euphorbia. The entire subtribe Euphorbiinae now consists solely of the genus Euphorbia.

Selected species

See List of Euphorbia species for complete list.

- Euphorbia albomarginata – Rattlesnake Weed, White-margined Sandmat

- Euphorbia amygdaloides – Wood Spurge

- Euphorbia antisyphilitica – Candelilla

- Euphorbia balsamifera – Sweet tabaiba (Canary Islands)[8]

- Euphorbia bulbispina

- Euphorbia canariensis – Cardón (Canary Islands)[9]

- Euphorbia cyparissias – Cypress Spurge

- Euphorbia decidua

- Euphorbia elastica – (Mexican) Palo Amarillo

- Euphorbia epithymoides – Cushion Spurge

- Euphorbia esula – Leafy Spurge

- Euphorbia franckiana

- Euphorbia grantii – African Milk Bush

- Euphorbia helioscopia – Sun Spurge

- Euphorbia heterophylla – Painted Euphorbia, Desert Poinsettia, (Mexican) Fireplant, Paint Leaf, Kaliko

- Euphorbia hirta - Used in Philippines as a traditional dengue remedy

- Euphorbia ingens

- Euphorbia labatii

- Euphorbia lactea – Mottled Spurge, Frilled Fan, Elkhorn

- Euphorbia lathyris – Caper Spurge, Paper Spurge, Gopher Spurge, Gopher Plant, Mole Plant

- Euphorbia maculata – Spotted Spurge, Prostrate Spurge

- Euphorbia marginata – Snow on the Mountain

- Euphorbia maritae

- Euphorbia milii – Crown-of-thorns, Christ Plant

- Euphorbia myrsinites – Myrtle Spurge, Creeping Spurge, donkey tail

- Euphorbia obesa

- Euphorbia paralias – Sea Spurge

- Euphorbia peplis – Purple Spurge

- Euphorbia peplus – Petty Spurge

- Euphorbia pulcherrima – Poinsettia, Mexican Flame Leaf, Christmas Star, Winter Rose, Noche Buena, Lalupatae, Pascua, Atatürk çiçeği (Turkish)

- Euphorbia resinifera – Resin Spurge

- Euphorbia rigida – Gopher Spurge, Upright Myrtle Spurge

- Euphorbia serrata – Serrated spurge, Sawtooth spurge

- Euphorbia tirucalli – Indian Tree Spurge, Milk Bush, Pencil Tree

- Euphorbia tithymaloides – Devil's Backbone, "Redbird cactus", cimora misha (Peru)

- Euphorbia virosa

Subgenera

The genus Euphorbia is one of the largest and most complex genera of flowering plants and several botanists have made unsuccessful attempts to subdivide the genus into numerous smaller genera. According to the recent phylogenetic studies,[6] Euphorbia can be divided into 4 subgenera, each containing several not yet sufficiently studied sections and groups. Of these, Esula is the most basal. Chamaesyce and Euphorbia are probably sister taxa but very closely related to Rhizanthium. Extensive xeromorph adaptations in all probability evolved several times; it is not known if the common ancestor of the cactus-like Rhizanthium and Euphorbia lineages was xeromorphic—in which case a more normal morphology would have re-evolved namely in Chamaesyce—or whether extensive xeromorphism is entirely polyphyletic even to the level of the subgenera.

- Esula

Wood Spurge |

Cypress Spurge |

Leafy Spurge |

Myrtle Spurge |

- Rhizanthium

Euphorbia ferox |

Euphorbia flanaganii |

Euphorbia meloformis ssp. valida |

Euphorbia obesa ssp. symmetrica |

- Chamaesyce

Euphorbia celastroides |

Painted Euphorbia |

Poinsettia |

Euphorbia rivae |

- Euphorbia

Euphorbia actinoclada |

Euphorbia attastoma var. attastoma |

Euphorbia confinalis ssp. rhodesica |

Euphorbia lupulina |

Footnotes

- ↑ Module 14: Hawaiian in A Mini-Course in Medical Botany

- ↑ tabaibas

- ↑ http://buscon.rae.es/draeI/SrvltConsulta?TIPO_BUS=3&LEMA=tabaiba

- ↑ Linnaeus (1753): p.450

- ↑ Eke, Al-Husainy, and Raynor, 'The Spectrum of Ocular Inflammation Caused by Euphorbia Plant Sap', Arch. Ophthalmol. (AMA) 118 (January 2000), pp. 13–16

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Steinmann & Porter (2002), Steinmann (2003), Bruyns et al. (2006)

- ↑ Steinmann, van Ee, Berry & Gutiérrez (2007) in Anales del Jardín Botánico de Madrid

- ↑ http://www.floradecanarias.com/euphorbia_balsamifera.html

- ↑ http://www.floradecanarias.com/euphorbia_canariensis.html

References

- Bruyns, Peter V. & al. (2006): A new subgeneric classification for Euphorbia (Euphorbiaceae) in southern Africa based on ITS and psbA-trnH sequence data. Taxon 55(2): 397–420. HTML abstract

- Buddensiek, Volker (2005): Succulent Euphorbia plus (CD-ROM). Volker Buddensiek Verlag.

- Carter, Susan (1982): New Succulent Spiny Euphorbias from East Africa

- Carter, Susan & Eggli, Urs (1997): The CITES Checklist of Succulent Euphorbia Taxa (Euphorbiaceae)

- Carter, Susan & Smith, A.L. (1988): Flora of Tropical East Africa, Euphorbiaceae

- Linnaeus, Carolus (1753): Species Plantarum (1st ed.)

- Noltee, Frans (2001): Succulents in the wild and in cultivation, Part 2 Euphorbia to Juttadinteria (CD-ROM)

- Eggli, Urs (ed.) (2002): Sukkulentenlexikon (Vol. 2: Zweikeimblättrige Pflanzen (Dicotyledonen)). Eugen Ulmer Verlag.

- Everitt, J.H.; Lonard, R.L., Little, C.R. (2007). Weeds in South Texas and Northern Mexico. Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press. ISBN 0-89672-614-2

- Pritchard, Albert (2003): Introduction to the Euphorbiaceae

- Schwartz, Herman (ed.) (1983): The Euphorbia Journal Strawberry Press, Mill Valley, California, USA

- Singh, Meena (1994): Succulent Euphorbiaceae of India. Mrs. Meena Singh, A-162 Sector 40, NOIDA, New Delhi, India.

- Steinmann, V.W. (2003): The submersion of Pedilanthus into Euphorbia (Euphorbiaceae). Acta Botanica Mexicana 65: 45–50. PDF fulltext [English with Spanish abstract]

- Steinmann, V.W. & Porter, J.M. (2002): Phylogenetic relationships in Euphorbieae (Euphorbiaceae) based on ITS and ndhF sequence data. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 89(4): 453–490. doi:10.2307/3298591 (HTML abstract, first page image)

- Turner, Roger (1995): Euphorbias—A Gardeners' Guide. Batsford, England.