Parameter

In mathematics, statistics, and the mathematical sciences, a parameter (G: auxiliary measure) is a quantity that serves to relate functions and variables using a common variable (often t) when such a relationship would be difficult to explicate with an equation. In different contexts the term may have special uses.

Contents |

Examples

- In a section on frequently misused words in his book The Writer's Art, James J. Kilpatrick quoted a letter from a correspondent, giving examples to illustrate the correct use of the word parameter:

| “ | W.M. Woods...a mathematician...writes... "...a variable is one of the many things a parameter is not." ... The dependent variable, the speed of the car, depends on the independent variable, the position of the gas pedal. | ” |

| “ | [Kilpatrick quoting Woods] "Now...the engineers...change the lever arms of the linkage...the speed of the car...will still depend on the pedal position...but in a...different manner. You have changed a parameter" | ” |

- A parametric equaliser is an audio filter that allows the frequency of maximum cut or boost to be set by one control, and the size of the cut or boost by another. These settings, the frequency level of the peak or trough, are two of the parameters of a frequency response curve, and in a two-control equaliser they completely describe the curve. More elaborate parametric equalisers may allow other parameters to be varied, such as skew. These parameters each describe some aspect of the response curve seen as a whole, over all frequencies. A graphic equaliser provides individual level controls for various frequency bands, each of which acts only on that particular frequency band.

- If asked to imagine the graph of the relationship y = ax2, one typically visualizes a range of values of x, but only one value of a. Of course a different value of a can be used, generating a different relation between x and y. Thus a is considered to be a parameter: it is less variable than the variable x or y, but it is not an explicit constant like the exponent 2. More precisely, changing the parameter a gives a different (though related) problem, whereas the variations of the variables x and y (and their interrelation) are part of the problem itself.

- In calculating income based on wage and hours worked (income equals wage multiplied by hours worked), it is typically assumed that the hours worked is easily changed, but the wage is more static. This makes wage a parameter in this formula.

Parameters in mathematics and science

Mathematical functions

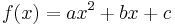

Mathematical functions have one or more arguments that are designated in the definition by variables, while their definition can also contain parameters. The variables are mentioned in the list of arguments that the function takes, but the parameters are not. When parameters are present, the definition actually defines a whole family of functions, one for every valid set of values of the parameters. For instance one could define a general quadratic function by defining

;

;

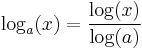

here the variable x designates the function argument, but a, b, and c are parameters that determine which quadratic function one is considering. The parameter could be incorporated into the function name to indicate its dependence on the parameter; for instance one may define the base a logarithm by

where a is a parameter that indicates which logarithmic function is being used; it is not an argument of the function, and will for instance be a constant when considering the derivative  .

.

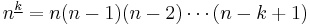

In some informal situations people regard it as a matter of convention (or historical accident) whether some or all the symbols in a function definition are called parameters. However changing the status of symbols between parameter and variable changes the function as a mathematical object. For instance the notation for the falling factorial power

,

,

defines a polynomial function of n (when k is considered a parameter), but is not a polynomial function of k (when n is considered a parameter); indeed in the latter case it is only defined at non-negative integer arguments.

In the special case of parametric equations the independent variables are called the parameters.

Mathematical models

In the context of a mathematical model, such as a probability distribution, the distinction between variables and parameters was described by Bard as follows:

- We refer to the relations which supposedly describe a certain physical situation, as a model. Typically, a model consists of one or more equations. The quantities appearing in the equations we classify into variables and parameters. The distinction between these is not always clear cut, and it frequently depends on the context in which the variables appear. Usually a model is designed to explain the relationships that exist among quantities which can be measured independently in an experiment; these are the variables of the model. To formulate these relationships, however, one frequently introduces "constants" which stand for inherent properties of nature (or of the materials and equipment used in a given experiment). These are the parameters.[1]

Analytic geometry

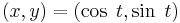

In analytic geometry, curves are often given as the image of some function. The argument of the function is invariably called "the parameter". A circle of radius 1 centered at the origin can be specified in more than one form:

- implicit form

- parametric form

- where t is the parameter.

A somewhat more detailed description can be found at parametric equation.

Mathematical analysis

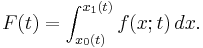

In mathematical analysis, integrals dependent on a parameter are often considered. These are of the form

In this formula, t is the argument of the function F, and on the right-hand side the parameter on which the integral depends. When evaluating the integral, t is held constant, and so it considered a parameter. If we are interested in the value of F for different values of t, then, we now consider it to be a variable. The quantity x is a dummy variable or variable of integration (confusingly, also sometimes called a parameter of integration).

Probability theory

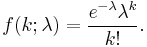

In probability theory, one may describe the distribution of a random variable as belonging to a family of probability distributions, distinguished from each other by the values of a finite number of parameters. For example, one talks about "a Poisson distribution with mean value λ". The function defining the distribution (the probability mass function) is:

This example nicely illustrates the distinction between constants, parameters, and variables. e is Euler's Number, a fundamental mathematical constant. The parameter λ is the mean number of observations of some phenomenon in question, a property characteristic of the system. k is a variable, in this case the number of occurrences of the phenomenon actually observed from a particular sample. If we want to know the probability of observing k1 occurrences, we plug it into the function to get  . Without altering the system, we can take multiple samples, which will have a range of values of k, but the system will always be characterized by the same λ.

. Without altering the system, we can take multiple samples, which will have a range of values of k, but the system will always be characterized by the same λ.

For instance, suppose we have a radioactive sample that emits, on average, five particles every ten minutes. We take measurements of how many particles the sample emits over ten-minute periods. The measurements will exhibit different values of k, and if the sample behaves according to Poisson statistics, then each value of k will come up in a proportion given by the probability mass function above. From measurement to measurement, however, λ remains constant at 5. If we do not alter the system, then the parameter λ is unchanged from measurement to measurement; if, on the other hand, we modulate the system by replacing the sample with a more radioactive one, then the parameter λ would increase.

Another common distribution is the normal distribution, which has as parameters the mean μ and the variance σ².

It is possible to use the sequence of moments (mean, mean square, ...) or cumulants (mean, variance, ...) as parameters for a probability distribution.

Statistics and econometrics

In statistics and econometrics, the probability framework above still holds, but attention shifts to estimating the parameters of a distribution based on observed data, or testing hypotheses about them. In classical estimation these parameters are considered "fixed but unknown", but in Bayesian estimation they are treated as random variables, and their uncertainty is described as a distribution.

It is possible to make statistical inferences without assuming a particular parametric family of probability distributions. In that case, one speaks of non-parametric statistics as opposed to the parametric statistics described in the previous paragraph. For example, Spearman is a non-parametric test as it is computed from the order of the data regardless of the actual values, whereas Pearson is a parametric test as it is computed directly from the data and can be used to derive a mathematical relationship.

Statistics are mathematical characteristics of samples which can be used as estimates of parameters, mathematical characteristics of the populations from which the samples are drawn. For example, the sample mean ( ) can be used as an estimate of the mean parameter (μ) of the population from which the sample was drawn.

) can be used as an estimate of the mean parameter (μ) of the population from which the sample was drawn.

Other fields

Other fields use the term "parameter" as well, but with a different meaning.

Logic

In logic, the parameters passed to (or operated on by) an open predicate are called parameters by some authors (e.g., Prawitz, "Natural Deduction"; Paulson, "Designing a theorem prover"). Parameters locally defined within the predicate are called variables. This extra distinction pays off when defining substitution (without this distinction special provision has to be made to avoid variable capture). Others (maybe most) just call parameters passed to (or operated on by) an open predicate variables, and when defining substitution have to distinguish between free variables and bound variables.

Engineering

In engineering (especially involving data acquisition) the term parameter sometimes loosely refers to an individual measured item. This usage isn't consistent, as sometimes the term channel refers to an individual measured item, with parameter referring to the setup information about that channel.

"Speaking generally, properties are those physical quantities which directly describe the physical attributes of the system; parameters are those combinations of the properties which suffice to determine the response of the system. Properties can have all sorts of dimensions, depending upon the system being considered; parameters are dimensionless, or have the dimension of time or its reciprocal."[2]

The term can also be used in engineering contexts, however, as it is typically used in the physical sciences.

Computer science

When the terms formal parameter and actual parameter are used, they generally correspond with the definitions used in computer science. In the definition of a function such as

- f(x) = x + 2,

x is a formal parameter. When the function is used as in

- y = f(3) + 5 or just the value of f(3),

3 is the actual parameter value that is substituted for the formal parameter in the function definition. These concepts are discussed in a more precise way in functional programming and its foundational disciplines, lambda calculus and combinatory logic.

In computing, parameters are often called arguments, and the two words are used interchangeably. However, some computer languages such as C define argument to mean actual parameter (i.e., the value), and parameter to mean formal parameter.

Linguistics

Within linguistics, the word "parameter" is almost exclusively used to denote a binary switch in a Universal Grammar within a Principles and Parameters framework.

References

See also

- Parametrization (i.e., coordinate system)

- Parametrization (climate)

- Parsimony (with regards to the trade-off of many or few parameters in data fitting)