Panama Canal Zone

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

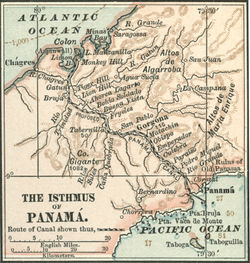

The Panama Canal Zone (Spanish: Zona del Canal de Panamá) was a 553 square mile (1,432 km2) unorganized U.S. territory located within the Republic of Panama, consisting of the Panama Canal and an area generally extending 5 miles (8.1 km) on each side of the centerline, but excluding Panama City and Colón, which otherwise would have fallen in part within the limits of the Canal Zone. Its border spanned two of Panama's provinces and was created on November 18, 1903 with the signing of the Hay-Bunau Varilla Treaty. When reservoirs were created to assure a steady supply of water for the locks, those lakes were included within the Zone.

On February 26, 1904, the Isthmian Canal Convention was proclaimed. In this, the Republic of Panama granted to the United States in perpetuity, the use, occupation and control of a zone of land and land under water for the construction, maintenance, operation, sanitation and protection of the canal.[1][2] From 1903 to 1979 the territory was controlled by the United States of America, which had built the canal and financed its construction. From 1979 to 1999 the canal itself was under joint U.S.-Panamanian control. In 1977 the Torrijos-Carter Treaties established the neutrality of the canal.[3]

Except during times of crisis or political tension, Panamanians could freely enter the Zone. In fact, normally anyone could walk across a street in Panama City and enter the jurisdiction. However, the 1903 treaty placed restrictions on the rights of Panamanians to buy at retail stores in the Zone. This was for the protection of Panamanian shopkeepers.

During U.S. control of the Canal Zone, the territory, apart from the canal itself, was used mainly for military purposes; however, approximately 3,000 American civilians (called "Zonians") made up the core of permanent residents. U.S. military usage ended when the zone was returned to Panamanian control. It has now been integrated into the economic development of Panama, and is a tourist destination of sorts, especially for visiting cruise ships.

Notable people born in the Panama Canal Zone include Richard Prince, Kenneth Bancroft Clark, Rod Carew, and John McCain, the Republican 2008 presidential candidate and US Senator from Arizona.

The largest U.S. Army unit based in the Canal Zone was the 193rd Infantry Brigade (Light), a mixed parachute-infantry/air-assault-capable light infantry unit. It was honored in 1994 as the first major unit to deactivate in accordance with the Panama Canal Treaty of 1977 treaty implementation plan, The brigade was reactivated in 2007, tasked with conducting basic combat training for new US Army recruits.

Documentary filmmaker Frederick Wiseman made a film about the Panama Canal Zone, entitled Canal Zone, which was released and shown on PBS in 1977.

Contents |

Governance of the Canal Zone

While the canal itself was operated by the Panama Canal Company – after 1979, it was the Panama Canal Commission – the Canal Zone Government controlled the Zone. This situation was described as a cross between a colonial company enclave and a socialist government. Everyone worked for the Company or the Government in one form or another. There were no independent stores, goods were brought in and sold at a series of stores run by the company, such as a commissary, housewares, and so on. Although denied by the government, for many years there was blatant racism in the Zone, with "gold" and "silver" facilities separated largely on the basis of color.[4]

The Canal Zone had its own police force (Canal Zone Police), courts, and judges (the United States District Court for the Canal Zone).

The head of the company was also the Governor of the Panama Canal Zone. Residents did not own their homes; instead they rented houses that were assigned, primarily based on seniority in the zone. When an employee moved away, the house would be listed and employees could apply for it. The utility companies were also managed by the company.

Tensions and the end of the Canal Zone

In 1903, the United States, having failed to obtain from Colombia the right to build a canal across the Isthmus of Panama, which was part of that country, sent warships in support of Panamanian independence from Colombia. This being achieved, the new nation of Panama ceded the Americans the rights they wanted in the Hay-Bunau Varilla Treaty. Over time, though, the existence of the Canal Zone, a political exclave of the U.S. that cut Panama geographically in half and had its own courts, police and civil government, became a cause of conflict between the two countries. Demonstrations occurred at the opening of the Bridge of the Americas in 1962 and serious rioting occurred in 1964.[5] This led to the United States easing its controls in the Zone. For example, Panamanian flags were allowed to be flown with American ones. After extensive negotiations the Canal Zone ceased to exist on October 1, 1979 in compliance with provisions of the Torrijos-Carter Treaties.

Citizenship

Although the Panama Canal Zone was legally an unincorporated U.S. territory until the implementation of the Torrijos-Carter Treaties in 1979, questions arose almost from its inception as to whether the Zone was considered part of the United States for constitutional purposes, or, in the phrase of the day, whether the Constitution followed the flag. In 1901 the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled in Downes v. Bidwell that unincorporated territories are not the United States.[6] On July 28, 1904, Controller of the Treasury Robert Tracewell stated: "While the general spirit and purpose of the Constitution is applicable to the zone, that domain is not a part of the United States within the full meaning of the Constitution and laws of the country."[7] Accordingly, it was held in 1905 in Rasmussen v. United States that the full constitution only applies for incorporated territories of the United States.[8] Until the rulings in these so-called "Insular Cases", children born of two U.S. citizens in the Canal Zone had been subject to the Naturalization Act of 1795, which granted statutory U.S. citizenship at birth. With the ruling of 1905 persons born in the Canal Zone only became U.S. nationals, not citizens.[9] This no man's land with regard to U.S. citizenship was perpetuated until Congress passed legislation in 1937, which corrected this deficiency. The law is now codified under title 8 section 1403.[10] It not only grants statutory and declaratory born citizenship to those born in the Canal Zone after February 26, 1904, with at least one U.S. citizen parent, but also did so retroactively for all children born of at least one U.S. citizen in the Canal Zone before the law's enactment.[11]

Townships and military installations

The Canal Zone was generally divided into two sections, the Pacific Side and the Atlantic Side, with Gatun Lake separating them.

A partial list of Canal Zone townships and military installations:

- Pacific Side

- Townships

- Ancón - built on the lower slopes of Ancon Hill, adjacent to Panama City. Also home to Gorgas Hospital.

- Balboa - Administrative capital, as well as location of the harbor and main Pacific Side high school

- Balboa Heights

- Cardenas - as the Canal Zone was gradually handed over to Panamanian control, Cardenas was one of the last Zonian holdouts.

- Cocoli

- Corozal

- Curundu: on military base, but housed civilian military workers

- Curundu Heights

- Diablo

- Diablo Heights

- Gamboa - headquarters of dredging division, located on Gatun Lake. Many new arrivals to the Canal Zone were assigned here.

- La Boca: home of the Panama Canal College

- Los Ríos

- Paraíso

- Pedro Miguel

- Red Tank: was abandoned and allowed to be overgrown sometime around 1950.

- Rosseau: built as a naval hospital during WWII, housed FAA personnel until Cardenas was built. Torn down after about 20 years

- Military Installations

- Fort Amador - on the coast, partly built on land extended into the sea using excavation materials from the canal construction

- Fort Clayton

- Corozal Army Post (close to, but separate from the civilian township)

- Fort Kobbe

- Rodman Marine Barracks

- Albrook Air Force Base

- Howard Air Force Base

- Quarry Heights: Headquarters, United States Southern Command

- Townships

- Atlantic Side

- Townships

- Brazos Heights: privately owned housing (by United Brands and other, mostly shipping companies) where employees/owners of shipping agencies, lawyers and the head of the YMCA lived

- Coco Solo: main hospital and only Atlantic Side high school (called Cristobal High School)

- Cristóbal: main harbor and port

- Gatún

- Margarita

- Mount Hope: site of the only Atlantic side cemetery and the only drydock

- Rainbow City

- Military Installations

- Fort Gulick: home to School of the Americas

- Galeta Island

- Fort Randolph: was located on Margarita island in Manzanillo bay

- Fort Davis

- Fort Sherman: home to Jungle Operations Training Center

- Townships

Postage stamps

See also

- Panama Railway

- Rail transport in Panama

- Transcontinental Railroad#Panama

- List of Governors of Panama Canal Zone

References

- ↑ Sandra W. Meditz; Dennis M. Hanratty, eds. (1987), "The 1903 Treaty and Qualified Independence", Panama: A Country Study, Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, http://countrystudies.us/panama/8.htm.

- ↑ Paul Halsall, ed., "Convention Between the US And Panama (Panama Canal), 1903", Modern History Sourcebook (Fordham University), http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/1903panama.html

- ↑ "Panamanian Control", Panama Canal, infoplease.com, http://www.infoplease.com/ce6/world/A0860218.html, retrieved 2008-06-02

- ↑ Rhonda D. Frederic (2005), Colón Man a Come": Mythographies Of Panama Canal Migration, Lexington Books, p. 33, ISBN :0739108913, http://books.google.com/?id=CSNTpYIB228C

- ↑ Panama Canal Zone - CZPolice

- ↑ United States Supreme Court, Downes v. Bidwell.

- ↑ (PDF) Not Part of United States, The New York Times, July 29, 1904, http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?res=9C06E1DF113BE631A2575AC2A9619C946597D6CF, retrieved 2008-06-02|

- ↑ United States Court of Appeals, Rasmussen v. United States.

- ↑ "Nationality" in: 7 FAM 1111.3 (c).

- ↑ 8 U.S.C. § 1403

- ↑ Cf. 8 U.S.C. § 1403, paragraph (a): "whether before or after the effective date of this chapter".

Further reading

- Murillo, Luis E. (1995). The Noriega Mess: The Drugs, the Canal, and Why America Invaded. 1096 pages, illustrated. Berkeley: Video Books. ISBN 0-923444-02-5.

- Mellander, Gustavo A. (1971) The United States in Panamanian Politics:The Intriguing Formative Years. Danville, Ill.: Interstate Publishers, OCLC 138568

- Mellander, Gustavo A.; Nelly Maldonado Mellander (1999). Charles Edward Magoon: The Panama Years. Río Piedras, Puerto Rico: Editorial Plaza Mayor. ISBN 1563281554. OCLC 42970390.

External links

- Lots of Panama Canal info, including data on military bases

- No More Tomorrows, From the Oct. 15, 1979 issue of TIME magazine

- Governor Parfitt's Address at Flag-lowering Ceremonies September 30, 1979

- More American than America, TIME magazine article Jan. 24, 1964 about Zonians, shortly after the Martyrs' Day riots

- Frederick Wiseman's documentary CANAL ZONE

- Maps of the Canal Zone

- Live Panama Canal webcams

- Air Defense of the Panama Canal 1958-1970

|

|||||||||||||||||||