Polycystic ovary syndrome

| Polycystic Ovary Syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

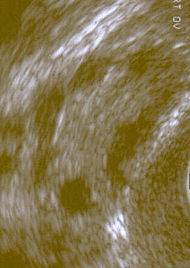

Polycystic ovary shown on ultrasound image |

|

| ICD-10 | E28.2 |

| ICD-9 | 256.4 |

| OMIM | 184700 |

| DiseasesDB | 10285 |

| eMedicine | med/2173 ped/2155 radio/565 |

| MeSH | D011085 |

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) is one of the most common female endocrine disorders affecting approximately 5%-10% of women of reproductive age (12–45 years old) and is thought to be one of the leading causes of female infertility.[1][2][3][4]

The principal features are obesity, anovulation (resulting in irregular menstruation) or amenorrhea, acne, and excessive amounts or effects of androgenic (masculinizing) hormones. The symptoms and severity of the syndrome vary greatly among women. While the causes are unknown, insulin resistance, diabetes, and obesity are all strongly correlated with PCOS.

Contents |

Nomenclature

Other names for this syndrome include polycystic ovarian syndrome (also PCOS), polycystic ovary disease (PCOD), functional ovarian hyperandrogenism, Stein-Leventhal syndrome (original name, not used in modern literature), ovarian hyperthecosis and sclerocystic ovary syndrome.

Definition

Two definitions are commonly used:

| In 1990 a consensus workshop sponsored by the NIH/NICHD suggested that a patient has PCOS if she has ALL of the following: | oligoovulation | signs of androgen excess (clinical or biochemical) |

---

|

other entities are excluded that would cause polycystic ovaries |

| In 2003 a consensus workshop sponsored by ESHRE/ASRM in Rotterdam indicated PCOS to be present if 2 out of 3 criteria are met[5] | oligoovulation and/or anovulation | excess androgen activity | polycystic ovaries (by gynecologic ultrasound) |

---

|

The Rotterdam definition is wider, including many more patients, notably patients without androgen excess, whereas in the NIH/NICHD definition androgen excess is a prerequisite. Critics maintain that findings obtained from the study of patients with androgen excess cannot necessarily be extrapolated to patients without androgen excess.[6][7]

Signs and symptoms

Common symptoms of PCOS include

- Oligomenorrhea, amenorrhea — irregular, few, or absent menstrual periods.

- Infertility, generally resulting from chronic anovulation (lack of ovulation).

- Hirsutism — excessive mild symptoms of hyperandrogenism, such as acne or hypermenorrhea, are frequent in adolescent girls and are often associated with irregular menstrual cycles. In most instances, these symptoms are transient and only reflect the immaturity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis during the first years following menarche.[8] Approximately three-fourths of patients with PCOS (by the diagnostic criteria of NIH/NICHD 1990) have evidence of hyperandrogenemia.[9]

PCOS can present in any age during the reproductive years. Due to its often vague presentation it can take years to reach a diagnosis.

Serum insulin, insulin resistance and homocysteine levels are significantly higher in subjects having PCOS but have no significant effect on fertility.[10]

Diagnosis

Not all women with PCOS have polycystic ovaries (PCO), nor do all women with ovarian cysts have PCOS; although a pelvic ultrasound is a major diagnostic tool, it is not the only one. The diagnosis is straightforward using the Rotterdam criteria, even when the syndrome is associated with a wide range of symptoms.

- Standard diagnostic assessments:

- History-taking, specifically for menstrual pattern, obesity, hirsutism, and the absence of breast development. A clinical prediction rule found that these four questions can diagnose PCOS with a sensitivity of 77.1% (95% confidence interval [CI] 62.7%–88.0%) and a specificity of 93.8% (95% CI 82.8%–98.7%).[11]

- Gynecologic ultrasonography, specifically looking for small ovarian follicles. These are believed to be the result of disturbed ovarian function with failed ovulation, reflected by the infrequent or absent menstruation that is typical of the condition. In normal menstrual cycle, one egg is released from a dominant follicle - essentially a cyst that bursts to release the egg. After ovulation the follicle remnant is transformed into a progesterone producing corpus luteum, which shrinks and disappears after approximately 12–14 days. In PCOS, there is a so called "follicular arrest", i.e., several follicles develop to a size of 5–7 mm, but not further. No single follicle reach the preovulatory size (16 mm or more). According to the Rotterdam criteria, 12 or more small follicles should be seen in a ovary on ultrasound examination. The follicles may be oriented in the periphery, giving the appearance of a 'string of pearls'. The numerous follicles contribute to the increased size of the ovaries, that is, 1.5 to 3 times larger than normal.

- Laparoscopic examination may reveal a thickened, smooth, pearl-white outer surface of the ovary. (This would usually be an incidental finding if laparoscopy were performed for some other reason, as it would not be routine to examine the ovaries in this way to confirm a diagnosis of PCOS).

- Serum (blood) levels of androgens (male hormones), including androstenedione, testosterone and Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate may be elevated.[12] The free testosterone level is thought to be the best measure,[13] with ~60% of PCOS patients demonstrating supranormal levels.[9] The Free androgen index of the ratio of testosterone to sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), is meant to be a predictor of free testosterone, but is a poor parameter for this and is no better than testosterone alone as a marker for PCOS,[14] possibly because FAI is correlated with the degree of obesity.[15]

- Some other blood tests are suggestive but not diagnostic. The ratio of LH (Luteinizing hormone) to FSH (Follicle stimulating hormone) is greater than 1:1, as tested on Day 3 of the menstrual cycle. The pattern is not very specific and was present in less than 50% in one study.[16] There are often low levels of sex hormone binding globulin, particularly among obese women.

- Common assessments for associated conditions or risks

- Fasting biochemical screen and lipid profile

- 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test (GTT) in patients with risk factors (obesity, family history, history of gestational diabetes) and may indicate impaired glucose tolerance (insulin resistance) in 15-30% of women with PCOS. Frank diabetes can be seen in 65–68% of women with this condition. Insulin resistance can be observed in both normal weight and overweight patients.

- For exclusion of other disorders that may cause similar symptoms:

- Prolactin to rule out hyperprolactinemia

- TSH to rule out hypothyroidism

- 17-hydroxyprogesterone to rule out 21-hydroxylase deficiency (congenital adrenal hyperplasia). Many such women may appear similar to PCOS and be made worse by insulin resistance or obesity, but they can be greatly helped by adrenal suppression with low-dose glucocorticoid therapy.

- Fasting insulin level or GTT with insulin levels (also called IGTT). Elevated insulin levels have been helpful to predict response to medication and may indicate women who will need higher dosages of metformin or the use of a second medication to significantly lower insulin levels. Elevated blood sugar and insulin values do not predict who responds to an insulin-lowering medication, low-glycemic diet, and exercise. Many women with normal levels may benefit from combination therapy. A hypoglycemic response in which the two-hour insulin level is higher and the blood sugar lower than fasting is consistent with insulin resistance. A mathematical derivation known as the HOMAI, calculated from the fasting values in glucose and insulin concentrations, allows a direct and moderately accurate measure of insulin sensitivity (glucose-level x insulin-level/22.5).

- Glucose tolerance testing (GTT) instead of fasting glucose can increase diagnosis of increased glucose tolerance and frank diabetes among patients with PCOS according to a prospective controlled trial.[17] While fasting glucose levels may remain within normal limits, oral glucose tests revealed that up to 38% of asymptomatic women with PCOS (versus 8.5% in the general population) actually had impaired glucose tolerance, 7.5% of those with frank diabetes according to ADA guidelines.[17]

Differential diagnosis

Other causes of irregular or absent menstruation and hirsutism, such as congenital adrenal hyperplasia, Cushing's syndrome, hyperprolactinemia, androgen secreting neoplasms, and other pituitary or adrenal disorders, should be investigated. PCOS has been reported in other insulin resistant situations such as acromegaly.

Pathogenesis

Polycystic ovaries develop when the ovaries are stimulated to produce excessive amounts of male hormones (androgens), particularly testosterone, either through the release of excessive luteinizing hormone (LH) by the anterior pituitary gland or through high levels of insulin in the blood (hyperinsulinaemia) in women whose ovaries are sensitive to this stimulus.

The syndrome acquired its most widely used name due to the common sign on ultrasound examination of multiple (poly) ovarian cysts. These "cysts" are actually immature follicles, not cysts ("polyfollicular ovary syndrome" would have been a more accurate name). The follicles have developed from primordial follicles, but the development has stopped ("arrested") at an early antral stage due to the disturbed ovarian function. The follicles may be oriented along the ovarian periphery, appearing as a 'string of pearls' on ultrasound examination. The condition was first described in 1935 by Dr. Stein and Dr. Leventhal, hence its original name of Stein-Leventhal syndrome.

PCOS is characterized by a complex set of symptoms, and the cause cannot be determined for all patients. However, research to date suggests that insulin resistance could be a leading cause. PCOS may also have a genetic predisposition, and further research into this possibility is taking place. No specific gene has been identified, and it is thought that many genes could contribute to the development of PCOS.

A majority of patients with PCOS have insulin resistance and/or are obese. Their elevated insulin levels contribute to or cause the abnormalities seen in the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis that lead to PCOS.

Adipose tissue possesses aromatase, an enzyme that converts androstenedione to estrone and testosterone to estradiol. The excess of adipose tissue in obese patients creates the paradox of having both excess androgens (which are responsible for hirsutism and virilization) and estrogens (which inhibits FSH via negative feedback).[18]

Also, hyperinsulinemia increases GnRH pulse frequency, LH over FSH dominance, increased ovarian androgen production, decreased follicular maturation, and decreased SHBG binding; all these steps lead to the development of PCOS. Insulin resistance is a common finding among patients of normal weight as well as those overweight patients.

PCOS may be associated with chronic inflammation, with several investigators correlating inflammatory mediators with anovulation and other PCOS symptoms.[19][20]

One study in the United Kingdom concluded that the risk of PCOS development was shown to be higher in lesbian women than in heterosexuals.[21][22] It should be noted however that all the participants in this study were referred after infertility was discovered or highly suspected and conclusion made is purely conjecture. Until further studies have been conducted and the research collaborated there is no assumption that female homosexuality will increase the occurrence of PCOS.

Management

Medical treatment of PCOS is tailored to the patient's goals. Broadly, these may be considered under four categories:

- Lowering of insulin levels

- Restoration of fertility

- Treatment of hirsutism or acne

- Restoration of regular menstruation, and prevention of endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer

In each of these areas, there is considerable debate as to the optimal treatment. One of the major reasons for this is the lack of large scale clinical trials comparing different treatments. Smaller trials tend to be less reliable and hence may produce conflicting results.

General interventions that help to reduce weight or insulin resistance can be beneficial for all these aims, because they address what is believed to be the underlying cause of the syndrome. Regular exercise and maintaining a healthy weight will help reduce the hormonal imbalance, restore ovulation and fertility, and improve acne and hirsutism.[23]

Insulin lowering

Diet

Where PCOS is associated with overweight or obesity, successful weight loss is probably the most effective method of restoring normal ovulation/menstruation, but many women find it very difficult to achieve and sustain significant weight loss. Low-carbohydrate diets and sustained regular exercise may help. Some experts recommend a low GI diet in which a significant part of total carbohydrates are obtained from fruit, vegetables and whole grain sources.[24]

Medications

Reducing insulin resistance by improving insulin sensitivity through medications such as metformin, and the newer thiazolidinedione (glitazones), have been an obvious approach and initial studies seemed to show effectiveness.[25] Although metformin is not licensed for use in PCOS, the United Kingdom's National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence recommended in 2004 that women with PCOS and a body mass index above 25 be given metformin when other therapy has failed to produce results.[26] However subsequent reviews in 2008 and 2009 have noted that randomised control trials have in general not shown the promise suggested by the early observational studies.[27][28]

Infertility

Not all women with PCOS have difficulty becoming pregnant. For those who do, anovulation is a common cause. Ovulation may be predicted by the use of urine tests that detect the preovulatory LH surge, called ovulation predictor kits (OPKs). However, OPKs are not always accurate when testing on women with PCOS.[29] Charting of cervical mucus may also be used to predict ovulation, or certain fertility monitors (those that track urinary hormones or changes in saliva) may be used. Methods that predict ovulation may be used to time intercourse or insemination appropriately.

While not useful for predicting ovulation,[30] basal body temperatures may be used to confirm ovulation. Ovulation may also be confirmed by testing for serum progesterone in mid-luteal phase, approximately seven days after ovulation (if ovulation occurred on the average cycle day of fourteen, seven days later would be cycle day 21). A mid-luteal phase progesterone test may also be used to diagnose luteal phase defect. Methods that confirm ovulation may be used to evaluate the effectiveness of treatments to stimulate ovulation.

For overweight women with PCOS, who are anovulatory, diet adjustments and weight loss are associated with resumption of spontaneous ovulation. For those who after weightloss still are anovulatory or for anovulatory lean women, clomiphene citrate and FSH are the principal treatments used to help infertility. Previously, even metformin was recommended treatment for anovulation. But in the largest trial to date, comparing clomiphene with metformin, clomiphene alone was the most effective.[31] In this trial, 626 women were randomized to three groups: metformin alone, clomiphene alone, or both. The live-birth rates following 6 months of treatment were 7.2% (metformin), 22.5% (clomiphene), and 26.8% (both). The major complication of clomiphene was multiple pregnancy, affecting 0%, 6% and 3.1% of women respectively. The overall success rates for live birth remained disappointing, even in women receiving combined therapy, but it is important to consider that the women in this trial had already been attempting to conceive for an average of 3.5 years, and over half had received previous treatment for infertility. Thus, these were women with significant fertility problems, and the live-birth rates are probably not representative of the typical PCOS woman. Following this study, the ESHRE/ASRM-sponsored Consensus workshop do not recommend metformin for ovulation stimulation.[32] Subsequent randomized studies have confirmed the lack of evidence for adding metformin to clomiphene.[33]

The most drastic increase in ovulation rate occurs with a combination of diet modification, weight loss, and treatment with metformin and clomiphene citrate.[34] It is currently unknown if diet change and weight loss alone have an effect on live birth rates comparable to those reported with clomiphene and metformin

For patients who do not respond to clomiphene, diet and lifestyle modification, there are options available including assisted reproductive technology procedures such as controlled ovarian hyperstimulation with FSH injections and in vitro fertilisation (IVF). Ovarian stimulation with FSH followed by hCG has an associated risk in women with PCOS of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome — an uncomfortable and potentially dangerous condition with morbidity and rare mortality. Thus recent developments have allowed the oocytes present in the multiple follicles to be extracted in natural, unstimulated cycles and then matured in vitro, prior to IVF. This technique is known as In vitro maturation (IVM).

The RCOG (The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists) has recently published an opinion paper on "METFORMIN THERAPY FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF WOMEN WITH POLYCYSTIC OVARY SYNDROME". The paper concluded that while initial studies appeared to be promising, more recent large randomised controlled trials have not observed beneficial effects of metformin either as first-line therapy or combined with clomifene citrate for the treatment of the anovulatory woman with PCOS. Most work has been undertaken in the management of anovulatory infertility and there are no good data from randomised controlled trials on the use of metformin in the management of other manifestations of PCOS. It is clear that the first aim for women with PCOS who are overweight is to make lifestyle changes with a combination of diet and exercise in order to lose weight and improve ovarian function. The European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology and American Society for Reproductive Medicine consensus on infertility treatment for PCOS concluded that there is no clear role for insulin sensitising and insulin lowering drugs in the management of PCOS, and should be restricted to those patients with glucose intolerance or type 2 diabetes rather than those with just insulin resistance. Therefore, on current evidence metformin is not a first line treatment of choice in the management of PCOS(RCOG December 2008)[1]

Though surgery is not commonly performed, the polycystic ovaries can be treated with a laparoscopic procedure called "ovarian drilling" (puncture of 4-10 small follicles with electrocautery), which often results in either resumption of spontaneous ovulations or ovulations after adjuvant treatment with clomiphene or FSH.

Hirsutism and acne

When appropriate (e.g. in women of child-bearing age who require contraception), a standard contraceptive pill may be effective in reducing hirsutism. A common choice of contraceptive pill is one that contains cyproterone acetate; in the UK/US the available brand is Dianette/Diane. Cyproterone acetate is a progestogen with anti-androgen effects that blocks the action of male hormones that are believed to contribute to acne and the growth of unwanted facial and body hair.

Other drugs with anti-androgen effects include flutamide and spironolactone, both of which can give some improvement in hirsutism. Spironolactone is probably the most-commonly used drug in the US. Metformin can reduce hirsutism, perhaps by reducing insulin resistance, and is often used if there are other features such as insulin resistance, diabetes or obesity that should also benefit from metformin. Eflornithine (Vaniqa) is a drug which is applied to the skin in cream form, and acts directly on the hair follicles to inhibit hair growth. It is usually applied to the face.

Although all of these agents have shown some efficacy in clinical trials, the average reduction in hair growth is generally in the region of 25%, which may not be enough to eliminate the social embarrassment of hirsutism, or the inconvenience of plucking/shaving. Individuals may vary in their response to different therapies, and it is usually worth trying other drug treatments if one does not work, but drug treatments do not work well for all individuals. For removal of facial hairs, electrolysis or laser treatments are faster and more efficient alternatives than the above mentioned medical therapies.

Menstrual irregularity and endometrial hyperplasia

If fertility is not the primary aim, then menstruation can usually be regulated with a contraceptive pill. The purpose of regulating menstruation is essentially for the woman's convenience, and perhaps her sense of well-being; there is no medical requirement for regular periods, so long as they occur sufficiently often (see below). Most brands of contraceptive pill result in a withdrawal bleed every 28 days if taken in 3-weeks periods. Dianette (a contraceptive pill containing cyproterone acetate) is also beneficial for hirsutism, and is therefore often prescribed in PCOS.

If a regular menstrual cycle is not desired, then therapy for an irregular cycle is not necessarily required - most experts consider that if a menstrual bleed occurs at least every three months, then the endometrium (womb lining) is being shed sufficiently often to prevent an increased risk of endometrial abnormalities or cancer. If menstruation occurs less often or not at all, some form of progestogen replacement is recommended. Some women prefer a uterine progestogen device such as the intrauterine system (Mirena) or the progestin implant (Implanon), which provides simultaneous contraception and endometrial protection for years. An alternative is oral progestogen taken at intervals (e.g. every three months) to induce a predictable menstrual bleeding.

Alternative approaches

D-chiro-inositol (DCI) offers a well-tolerated and effective alternative treatment for PCOS. It has been evaluated in two peer-reviewed, double-blind studies and found to help both lean and obese women with PCOS; diminishing many of the primary clinical presentations of PCOS.[35][36] It has no documented side-effects and is a naturally occurring human metabolite known to be involved in insulin metabolism.[37] DCI is regulated as a dietary supplement in the United States.

Prognosis

Women with PCOS are at risk for the following:

- Endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer (cancer of the uterine lining) are possible, due to overaccumulation of uterine lining, and also lack of progesterone resulting in prolonged stimulation of uterine cells by estrogen. It is however unclear if this risk is directly due to the syndrome or from the associated obesity, hyperinsulinemia, and hyperandrogenism[38][39][40][41]

- Insulin resistance/Type II diabetes. A review published in 2010 concluded that women with PCOS had an elevated prevalence of insulin resistance and type II diabetes, also when controlling for body mass index (BMI).[42]

- High blood pressure

- Depression/Depression with Anxiety

- Dyslipidemia - disorders of lipid metabolism — cholesterol and triglycerides. PCOS patients show decreased removal of atherosclerosis-inducing remnants, seemingly independent on insulin resistance/Type II diabetes.[43]

- Cardiovascular disease

- Strokes

- Weight gain

- Miscarriage[1][2]

- Acanthosis nigricans (patches of darkened skin under the arms, in the groin area, on the back of the neck)

- Autoimmune thyroiditis [44]

See also

- Androgen-dependent syndromes

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Goldenberg N, Glueck C (2008). "Medical therapy in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome before and during pregnancy and lactation". Minerva Ginecol 60 (1): 63–75. PMID 18277353.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Boomsma CM, Fauser BC, Macklon NS (2008). "Pregnancy complications in women with polycystic ovary syndrome". Semin. Reprod. Med. 26 (1): 72–84. doi:10.1055/s-2007-992927. PMID 18181085.

- ↑ Palacio JR et,al.The presence of antibodies to oxidative modified proteins in serum from polycystic ovary syndrome patients Clin Exp Immunol. 2006 May;144(2):217-22.PMID 16634794

- ↑ Azziz R. et.al.The prevalence and features of the polycystic ovary syndrome in an unselected population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004 Jun;89(6):2745-9. PMID 15181052

- ↑ Azziz R.Controversy in clinical endocrinology: diagnosis of polycystic ovarian syndrome: the Rotterdam criteria are premature. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Mar;91(3):781-5. Epub 2006 Jan 17. PMID 16418211

- ↑ Carmina E. Diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome: from NIH criteria to ESHRE-ASRM guidelines.Minerva Ginecol. 2004 Feb;56(1):1-6. PMID 14973405

- ↑ Hart R, Hickey M, Franks S.Definitions, prevalence and symptoms of polycystic ovaries and polycystic ovary syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2004 Oct;18(5):671-83. PMID 15380140

- ↑ Christine Cortet-Rudelli, Didier Dewailly (Sep 21 2006). "Diagnosis of Hyperandrogenism in Female Adolescents". Hyperandrogenism in Adolescent Girls. Armenian Health Network, Health.am. http://www.health.am/gyneco/more/diagnosis-of-hyperandrogenism-in-female/. Retrieved 2006-11-21.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Huang A, Brennan K, Azziz R (April 2010). "Prevalence of hyperandrogenemia in the polycystic ovary syndrome diagnosed by the National Institutes of Health 1990 criteria". Fertil. Steril. 93 (6): 1938–41. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.138. PMID 19249030.

- ↑ Nafiye Y, Sevtap K, Muammer D, Emre O, Senol K, Leyla M (April 2010). "The effect of serum and intrafollicular insulin resistance parameters and homocysteine levels of nonobese, nonhyperandrogenemic polycystic ovary syndrome patients on in vitro fertilization outcome". Fertil. Steril. 93 (6): 1864–9. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.024. PMID 19171332.

- ↑ Pedersen SD, Brar S, Faris P, Corenblum B (2007). "Polycystic ovary syndrome: validated questionnaire for use in diagnosis". Canadian family physician Médecin de famille canadien 53 (6): 1042–7, 1041. PMID 17872783. PMC 1949220. http://www.cfp.ca/cgi/content/full/53/6/1041#T50531041. - see Table 5 Clinical tool for diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome

- ↑ Somani N, Harrison S, Bergfeld WF (2008). "The clinical evaluation of hirsutism". Dermatologic therapy 21 (5): 376–91. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00219.x. PMID 18844715.

- ↑ Sharquie KE, Al-Bayatti AA, Al-Ajeel AI, Al-Bahar AJ, Al-Nuaimy AA (July 2007). "Free testosterone, luteinizing hormone/follicle stimulating hormone ratio and pelvic sonography in relation to skin manifestations in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome". Saudi Med J 28 (7): 1039–43. PMID 17603706.

- ↑ Robinson S, Rodin DA, Deacon A, Wheeler MJ, Clayton RN (March 1992). "Which hormone tests for the diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome?". Br J Obstet Gynaecol 99 (3): 232–8. PMID 1296589.

- ↑ Li X, Lin JF (December 2005). "[Clinical features, hormonal profile, and metabolic abnormalities of obese women with obese polycystic ovary syndrome]" (in Chinese). Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 85 (46): 3266–71. PMID 16409817.

- ↑ Banaszewska B, Spaczyński RZ, Pelesz M, Pawelczyk L (2003). "Incidence of elevated LH/FSH ratio in polycystic ovary syndrome women with normo- and hyperinsulinemia". Rocz. Akad. Med. Bialymst. 48: 131–4. PMID 14737959.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Legro RS, Kunselman AR, Dodson WC, Dunaif A (1999). "Prevalence and predictors of risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance in polycystic ovary syndrome: a prospective, controlled study in 254 affected women". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 84 (1): 165–9. doi:10.1210/jc.84.1.165. PMID 9920077. http://jcem.endojournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=9920077.

- ↑ Kumar Cotran Robbins: Basic Pathology 6th ed. / Saunders 1996

- ↑ Fukuoka M, Yasuda K, Fujiwara H, Kanzaki H, Mori T (1992). "Interactions between interferon gamma, tumour necrosis factor alpha, and interleukin-1 in modulating progesterone and oestradiol production by human luteinized granulosa cells in culture.". Hum Reprod 7 (10): 1361–4. PMID 1291559.

- ↑ González F, Rote N, Minium J, Kirwan J (2006). "Reactive oxygen species-induced oxidative stress in the development of insulin resistance and hyperandrogenism in polycystic ovary syndrome.". J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91 (1): 336–40. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-1696. PMID 16249279.

- ↑ Agrawal R, Sharma S, Bekir J, Conway G, Bailey J, Balen AH, Prelevic G. (2004). "Prevalence of polycystic ovaries and polycystic ovary syndrome in lesbian women compared with heterosexual women.". JFertil Steril 82 (5): 1352–7.. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.04.041. PMID 15533359.

- ↑ Hormone imbalance more common in lesbians. http://www.abc.net.au/science/news/stories/2003/892229.htm?health

- ↑ http://www.megavista-health.com/articles/health-conditions/polycystic-ovary-syndrome-pcos

- ↑ Marsh K, Brand-Miller J (August 2005). "The optimal diet for women with polycystic ovary syndrome?". Br. J. Nutr. 94 (2): 154–65. doi:10.1079/BJN20051475. PMID 16115348. http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0007114505001674.

- ↑ Lord JM, Flight IHK, Norman RJ (2003). "Metformin in polycystic ovary syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ 327 (7421): 951–3. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7421.951. PMID 14576245. PMC 259161. http://www.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/327/7421/951.

- ↑ National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. 11 Clinical guideline 11 : Fertility: assessment and treatment for people with fertility problems . London, 2004.

- ↑ Balen A (December 2008). "Metformin therapy for the management of infertility in women with polycystic ovary syndrome" (PDF). Scientific Advisory Committee Opinion Paper 13. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. http://www.rcog.org.uk/files/rcog-corp/uploaded-files/SAC13metformin-minorrevision.pdf. Retrieved 2009-12-13.

- ↑ Leeman L, Acharya U (August 2009). "The use of metformin in the management of polycystic ovary syndrome and associated anovulatory infertility: the current evidence". J Obstet Gynaecol 29 (6): 467–72. doi:10.1080/01443610902829414. PMID 19697191.

- ↑ "Question about opks with pcos". http://www.experts123.com/q/question-about-opks-with-pcos.html. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ↑ Guermandi E, Vegetti W, Bianchi MM, Uglietti A, Ragni G, Crosignani P (2001). "Reliability of ovulation tests in infertile women" (– Scholar search). Obstet Gynecol 97 (1): 92–6. doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(00)01083-8. PMID 11152915. http://www.greenjournal.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11152915.

- ↑ Legro RS, Barnhart HX, Schlaff WD (2007). "Clomiphene, Metformin, or Both for Infertility in the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome". N Engl J Med 356 (6): 551–66. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa063971. PMID 17287476.

- ↑ Thessaloniki ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group (March 2008). "Consensus on infertility treatment related to polycystic ovary syndrome". Fertil. Steril. 89 (3): 505–22. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.09.041. PMID 18243179.

- ↑ Johnson NP, Stewart AW, Falkiner J, et al. (April 2010). "PCOSMIC: a multi-centre randomized trial in women with PolyCystic Ovary Syndrome evaluating Metformin for Infertility with Clomiphene". Hum Reprod. doi:10.1093/humrep/deq100. PMID 20435692.

- ↑ Andy C, Flake D, French L (2005). "Clinical inquiries. Do insulin-sensitizing drugs increase ovulation rates for women with PCOS?". J Fam Pract 54 (2): 156, 159–60. PMID 15689292. http://www.jfponline.com/Pages.asp?AID=1867.

- ↑ Nestler J E, Jakubowicz D J, Reamer P, Gunn R D, Allan G (1999). "Ovulatory and metabolic effects of D-chiro-inositol in the polycystic ovary syndrome". N Engl J Med 340 (17): 1314–20. doi:10.1056/NEJM199904293401703. PMID 10219066.

- ↑ Iuorno M J, Jakubowicz D J, Baillargeon J P, Dillon P, Gunn R D, Allan G, Nestler J E (2002). "Effects of d-chiro-inositol in lean women with the polycystic ovary syndrome". Endocr Pract 8 (6): 417–23. PMID 15251831.

- ↑ Larner J (2002). "D-chiro-inositol--its functional role in insulin action and its deficit in insulin resistance". Int J Exp Diabetes Res 3 (1): 47–60. doi:10.1080/15604280212528. PMID 11900279.

- ↑ New MI.Nonclassical congenital adrenal hyperplasia and the polycystic ovarian syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993 May 28;687:193-205.PMID 8323173

- ↑ Hardiman P, Pillay OC, Atiomo W.Polycystic ovary syndrome and endometrial carcinoma.Lancet. 2003 May 24;361(9371):1810-2.PMID 12781553

- ↑ Mather KJ, Kwan F, Corenblum B.Hyperinsulinemia in polycystic ovary syndrome correlates with increased cardiovascular risk independent of obesity. Fertil Steril. 2000 Jan;73(1):150-6.PMID 10632431

- ↑ Unfer V, Zacchè M, Serafini A, Redaelli A, Papaleo E.Minerva Ginecol. 2008 Oct;60(5):363-8. Treatment of hyperandrogenism and hyperinsulinemia in PCOS patients with essential amino acids. A pilot clinical study.PMID 18854802

- ↑ Moran LJ, Misso ML, Wild RA, Norman RJ (May 2010). "Impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Hum Reprod Update 16 (4): 347–63. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq001. PMID 20159883.

- ↑ Rocha MP, Maranhão RC, Seydell TM, et al. (April 2010). "Metabolism of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and lipid transfer to high-density lipoprotein in young obese and normal-weight patients with polycystic ovary syndrome". Fertil. Steril. 93 (6): 1948–56. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.044. PMID 19765700.

- ↑ Troischt MJ, Mehlman TR, and Nield LS (November 1, 2008). "Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: An Intriguing Diagnosis". Consultant for Pediatricians. http://www.consultantlive.com/consultant-for-pediatricians/article/1145470/1404582.

External links

- 4women.gov Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS)

- The University of Chicago Center for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

- Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome Association of Australia POSAA

- PCOS Foundation

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||