Oto-Manguean languages

| Oto-Manguean | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution: |

Today: Mexico - Earlier: Mesoamerica and Central America |

| Linguistic Classification: | Not positively related to any other language families. |

| Subdivisions: |

Oto-Pamean

Chinantecan

Tlapanecan

Manguean

Popolocan

Zapotecan

Amuzgoan

Mixtecan

|

| ISO 639-5: | omq |

|

|

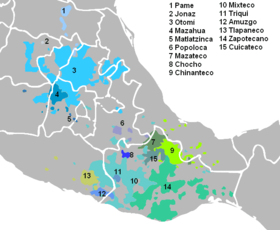

Oto-Manguean languages (also Otomanguean, pronounced /ˌɒtɵˈmæŋɡiən/ or English pronunciation: /ˌɒtɵˈmɑːŋɡiən/) are a large family comprising several families of Native American languages. All of the Oto-Manguean languages that are now spoken are indigenous to Mexico, but Oto-Manguean languages that are now extinct were spoken as far south as Nicaragua. The highest number of speakers of Oto-Manguean languages today are found in the state of Oaxaca where the two largest branches, the Zapotecan and Mixtecan languages, are spoken by almost 1.5 million people combined. In central Mexico, particularly in the states of Mexico (state), Hidalgo and Querétaro, the languages of the Oto-Pamean branch are spoken: the Otomi and the closely related Mazahua have over 500,000 speakers combined. Some Oto-Manguean languages are moribund or highly endangered; for example, Ixcatec and Matlatzinca each has fewer than 250 speakers, most of whom are elderly. Other languages particularly of the Manguean branch which was spoken outside of Mexico have become extinct; these include the Chiapanec language, which has only recently been declared extinct. Others such as Subtiaba, which was very similar to Me'phaa (Tlapanec), have been extinct longer and are only known from early 20th century descriptions.

The Oto-Manguean languages have coexisted with the other languages of Mesoamerica and have developed many traits in common with these, to such an extent that they are seen as part of a "sprachbund" called the Mesoamerican Linguistic Area. However Oto-Manguean also stands out from the other language families of Mesoamerica in several features. It is the only language family in North America, Mesoamerica and Central America whose members are all tonal languages. It also stands out by having a much more analytic structure than other Mesoamerican languages. Another typical trait of Oto-Manguean is that its members almost all show VSO (Verb Subject Object) in basic order of clausal constituents.

Contents |

History of classification

Internal classification

A genetic relationship between Zapotecan and Mixtecan was first proposed by Orozco y Berra in 1864, he also included Cuicatec, Chocho and Amuzgo in his grouping. In 1865 Pimentel added Mazatec, Popoloca, Chatino and Chinantec - he also posed a separate group of Pame, Otomi and Mazahua, the beginning of the Oto-Pamean subbranch. Daniel Brinton's classification of 1891 added Matlatzinca and Chichimeca Jonaz to Pimentel's Oto-Pamean group (which wasn't known by that name then), and he reclassified some languages of the previously included languages of the Oaxacan group. In 1920 Lehmann included the Chiapanec-Mangue languages and correctly establishd the major subgroupings of the Oaxacan group. And in 1926 Schmidt coined the name Otomi-Mangue for a group consisting of the Oto-pamean languages and Chiapanec-Mangue. The Oto-Pamean group and the Main Oaxacan group were not joined together into one family until in Sapir's classification 1929. From the 1950s on reconstructive work began to be done on Oto-Manguean which led to a better understanding of subgroupings within the family. Proto–Oto-Pamean was reconstructed by Doris Bartholomew, Proto-Zapotecan by Morris Swadesh, Proto–Chiapanec-Mangue by Fernández de Miranda and Weitlaner. And the first reconstruction of Proto–Oto-Manguean was done by Longacre in 1957. This reconstruction as later refined by himself and later by Rensch.

Tlapanec (Me'phaa) and Subtiaba, which had been seen as related already by Lehmann but which had been included in Sapir's Hokan grouping were not to be included in the family until 1977 when Jorge A Suárez demonstrated the relationship. The classification by Campbell 1997 was the first to present a unified view of the Oto-Manguean languages including Tlapanec-Subtiaba.

Inclusion in macro-family hypotheses

Edward Sapir included Subtiaba-Tlapanec in his Hokan phylum, but didn't classify the other Oto-Manguean languages in his famous 1929 classification. Although by 1987 when Joseph Greenberg made his controversial three family classification Tlapanec had been unequivocally linked to Oto-Manguean he continued to classify Tlapanec in the Hokan subgroup of his Amerind super-family but the other Oto-Manguean languages as "Central Amerind". No hypotheses including Oto-Manguean in any other higher level genetic unit have been able to stand up to scrutiny. At 6-7000 thousand years the time depth of the Oto-Manguean family is also so great that finding positive connections to other linguistic groups seem improbable.

Prehistory

The Oto-Manguean family has existed in southern Mexico at least since 4000 BCE and probably before. The Oto-Manguean urheimat has been thought to be in the Tehuacan valley in connection with one of the earliest neolithic cultures of Mesoamerica, and although it is now in doubt whether Tehuacán was the original home of the Proto-Otomanguean people, it is agreed that the Tehuacán culture (5000 BCE–2300 BCE) were Oto-Mangue speakers.[1] The long history of the Oto-Manguean family has resulted in considerable linguistic diversity between the branches of the family. Oto-Mangue speakers have been among the earliest to form highly complex cultures of Mesoamerica - the Archeological site of Monte Albán with remains dated as early as 1000 BCE is believed to have been in continuous use by Zapotecs. Other Mesoamerican cultural centers which may have been wholly or partly Oto-Manguean include the late classical sites of Xochicalco, which may have been built by Matlatzincas, and Cholula, which may have been inhabited by Manguean peoples. And some even speculate an Oto-Manguean influence in Teotihuacán. The Zapotecs are among the candidates to have invented the first writing system of Mesoamerica - and in the Post-classic period the Mixtecs were prolific artesans and codex-painters. During the postclassic the Oto-Manguean cultures of Central Mexico became marginalized by the intruding Nahuas and some, like the Chiapanec-Mangue speakers went south into Guerrero, Chiapas and Central America, while others such as the Otomi saw themselves relocated from their ancient homes in the Valley of Mexico to the less fertile highlands on the rim of the valleys.

Present distribution in southern Mexico

Genealogy

| Genealogical classification of Oto-Manguean languages | |||||

| Family | Groups | Languages | Where spoken and approximate number of speakers | ||

| Oto-Manguean languages | Western Oto-Mangue | Oto-Pame-Chinantecan | Oto-Pamean | Otomi languages (Hñähñu) (several varieties) | Central México (~212,000) |

| Mazahua (Hñatho) | México (state) (~350,000) | ||||

| Matlatzinca | México (state). Two varieties: Ocuiltec/Tlahuica (~450) and Matlatzinca de San Francisco (~1,300) | ||||

| Pame | San Luis Potosí. Three varietes: Southern Pame (presumed to have no speakers), Central Pame (~5,000), Northern Pame (~5,000). | ||||

| Chichimeca-Jonaz | Guanajuato, San Luis Potosí (~1,500) | ||||

| Chinantecan | Chinantec | northern Oaxaca and southern Veracruz, (~224,000) | |||

| Tlapanec-Mangue | Tlapanecan | Tlapanec ( Me'phaa) | Guerrero (~75,000) | ||

| Subtiaba (†) | Honduras | ||||

| Manguean | Chiapanec (†) | Chiapas | |||

| Mangue (†) | Nicaragua | ||||

| Chorotega (†) | Costa Rica | ||||

| Eastern Oto-Mangue | Popolocan-Zapotecan | Popolocan languages | Mazatec | north-eastern Oaxaca and Veracruz (~206,000) | |

| Ixcatec | northern Oaxaca (<100) | ||||

| Chocho language | northern Oaxaca (<1000) | ||||

| Popolocan languages | Southern Puebla, (~30,000) | ||||

| Zapotecan languages | Zapotec languages (around 50 variants) | Central and eastern Oaxaca (~785,000) | |||

| Chatino | Oaxaca (~23,000) | ||||

| Papabuco | Oaxaca | ||||

| Soltec | Oaxaca | ||||

| Amuzgo-Mixtecan[2] | Amuzgoan | Amuzgo (around 4 variants) | Oaxaca y Guerrero (~44,000) | ||

| Mixtecan | Mixtec languages (around 30 variants) | central, southern and western Oaxaca; southern Puebla and eastern Guerrero (~511,000) | |||

| Cuicatec | Cuicatlán, Oaxaca, (~18,500) | ||||

| Trique (also called Triqui) | western Oaxaca (~23,000) | ||||

| Oto-Manguean |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Phonological overview

Common phonological traits

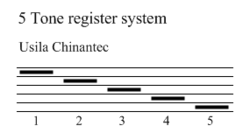

All Oto-Manguean languages have tone: some have only two level tones while others have up to five level tones. Many languages in addition have a number of contour tones. Many Oto-Manguean languages have phonemic vowel nasalization. Many Oto-Manguean languages lack labial consonants, particularly stops and those that do have labial stops normally have these as a reflex of Proto–Oto-Manguean */kʷ/.

Syllable structure

Proto–Oto-Manguean allowed only open syllables of the structure CV (or CVʔ). Syllable initial consonant clusters are very limited, usually only sibilant-CV, CyV, CwV, nasal-CV, ChV, or CʔV are allowed. Many modern Oto-Manguean languages keep these restrictions in syllable structure but others, most notably the Oto-Pamean languages, now allow both final clusters and long syllable initial clusters. This example with three initial and three final consonants is from Northern Pame: /nlʔo2spt/ "their houses".[3]

Phonemes of Proto–Oto-Manguean

The following phonemes are reconstructed for Proto–Oto-Manguean.[4]

| Reconstructed consonant phonemes of Proto–Oto-Manguean | ||||||||||||

| Labiovelar | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stops | *kʷ | *t | *k | *ʔ | ||||||||

| Fricatives | *s | |||||||||||

| Nasals | *n | |||||||||||

| Glides | *w | *j | ||||||||||

| Reconstructed vowel phonemes of Proto–Oto-Manguean | ||||||||||||

| Front | Central | Back | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *i | *u | |||||||||||

| *e | ||||||||||||

| *a | ||||||||||||

Rensch also reconstructs four tones for Proto–Oto-Manguean.[5] A later revised reconstruction by Terrence Kaufman[6] adds the proto-phonemes */ts/, */θ/, */x/, */xʷ/, */l/, */r/, */m/ and */o/, and the vowel combinations */ia/, */ai/, */ea/, and */au/.

The Oto-Manguean languages have changed quite a lot from the very spartan phoneme inventory of Proto–Oto-Manguean. Many languages have rich inventories of both vowels and consonants. Many have a full series of fricatives, and some branches (particularly Zapotecan and Chinantecan) distinguish voicing in both stops and fricatives. The voiced series of the Oto-Pamean languages have both fricative and stop allophones. Otomian also have full series of front, central and back vowels. Some analyses of Mixtecan include a series of voiced prenasalised stops and affricates - these can also be analysed as consonant sequences but it would be the only consonant clusters known in the languages.

These are some of the most simple sound changes that have served to divide the Oto-Manguean family into subbranches:

-

- /t/ to /tʃ/ in Chatino

- /kʷ/ to /p/ in Chiapanec-Mangue, Oto-Pame and Isthmus Zapotec

- /s/ to /θ/ in Mixtecan

- /s/ to /t/ in Chatino

- /w/ to /o/ before vowels in Oto-Pame

- /j/ to /i/ before vowels in Oto-Pame and Amuzgo

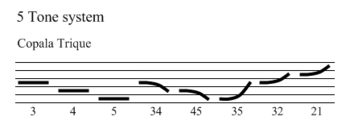

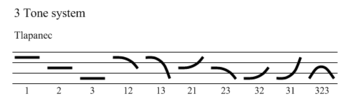

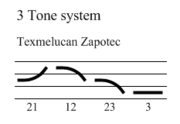

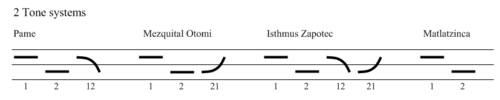

Tone systems

The Oto-Manguean languages have a wide range of tonal systems, some with as many as 10 tone contrasts and others with only two. Some languages have a register system only distinguishing tones by the relative pitch. Others have a contour system that also distinguishes tones with gliding pitch. Most however are combinations of the register and contour systems. Tone as a distinguishing feature is entrenched in the structure of the Oto-Manguean languages and in no way a peripheral phenomenon as it is in some languages that are known to have acquired tone recently or which are in a process of losing it. In most Oto-Manguean languages tone serves to distinguish both between the meanings of roots and to indicate different grammatical categories. In Chiquihuitlan Mazatec which has four tones the following minimal pairs occur: tʃa1 "I talk", tʃa² "difficult", tʃa³ "his hand" tʃa4 "he talks".[7]

The language with the most level tones is Usila Chinantec which has five level tones and no contour tones; Trique of Chicahuaxtla has a similar system.[7]

In Copala Trique, which has a mixed system, only three level tones but five tonal registers are distinguished within the contour tones.

Many other systems have only three tones levels, such as Tlapanec and Texmelucan Zapotec.

Particularly common in the Oto-Pamean branch are small tonal systems with only two level tones and one combination, such as Pame and Otomi. Some others like Matlatzinca and Chichimeca Jonaz only have the level tones and no combination.

In some languages stress influences tone, for example in Pame only stressed syllables have a tonal contrast. In Chatino where stress falls predictably on the last syllable of polysyllables, tone is also only distinguished on the last syllable. In Mazahua The opposite occurs and all syllables except the final stressed one distinguishes tone. In Tlapanec stress is determined by the tonal contour of the words. Most languages have systems of sandhi where the tones of a word or syllable are influenced by other tones in other syllables or words. Chinantec has no Sandhi rules but Mixtec and Zapotec have elaborate systems. For Mazatec some dialects has elaborate Sandhi systems (e.g. Soyaltepec) and others haven't (e.g. Huautla Mazatec). Some languages (particularly Mixtecan) also have terrace systems where some tones are "Upstep" or "Downstep" causing a raise or drop in pitch level for the entire tonal register in subsequent syllables.

Whistled speech

Several Oto-Manguean languages have systems of whistled speech, where by whistling the tonal combinations of words and phrases, information can be transmitted over distances without using words. Whistled speech is particularly common in Chinantec, Mazatec and Zapotecan languages.

Notes

References

-

-

- Bartholomew, Doris (October 1960). "Some revisions of Proto-Otomi consonants". International Journal of American Linguistics 26 (4): 317–329. doi:10.1086/465017. JSTOR 1263568.

- Campbell, Lyle (1997). American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America (Oxford Studies in Anthropological Linguistics, 4). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-195-09427-1.

- Rensch, Calvin (1977). "Classification of the Oto-Manguean Languages and the position of Tlapanec". In David Oltrogge and Calvin Rensch (eds.). Two Studies in Middle American Comparative Linguistics. Publications in Linguistics, Publication Number 55. Summer Institute of Linguistics. pp. 53–108.

- Suárez, Jorge A. (1977) (MS). El tlapaneco como lengua Otomangue. México, D.F.: Universidad Nacional Autonoma de México. (Spanish)

- Suárez, Jorge A. (1983). The Mesoamerican Indian Languages. Cambridge Language Surveys. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-22834-4.

- Longacre, Robert (1968). "Systemic Comparison and Reconstruction". In Norman A. McQuown (Volume ed.). Handbook of Middle American Indians, Vol. 5: Linguistics. R. Wauchope (General Editor). Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 117–159. ISBN 0-292-73665-7. OCLC 277126.

- Newman, Stanley; Roberto weitlaner (1950a). "Central Otomian I:Proto-Otomian reconstructions". International Journal of American Linguistics 16 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1086/464056. JSTOR 1262748.

- Newman, Stanley; Roberto weitlaner (1950b). "Central Otomian II:Primitive central otomian reconstructions". International Journal of American Linguistics 16 (2): 73–81. doi:10.1086/464067. JSTOR 1262851.

-

External links

- SIL on the Oto-Manguean Stock

- Why you should study an endangered Oto-Manguean languagePDF (82.9 KiB), by Rosemary Beam de Azcona