Frankincense

Frankincense, also called olibanum (Arabic: لبٌان, lubbān), is an aromatic resin obtained from trees of the genus Boswellia, particularly Boswellia sacra (syn. B. carteri, B. thurifera), B. frereana, and B. bhaw-dajiana (Burseraceae). It is used in incense and perfumes.

There are four main species of Boswellia which produce true frankincense and each type of resin is available in various grades. The grades depend on the time of harvesting, and the resin is hand-sorted for quality.

Contents |

Description

Frankincense is tapped from the very scraggly but hardy Boswellia tree by slashing the bark and allowing the exuded resins to bleed out and harden. These hardened resins are called tears. There are numerous species and varieties of frankincense trees, each producing a slightly different type of resin. Differences in soil and climate create even more diversity of the resin, even within the same species.

Frankincense trees are also considered unusual for their ability to grow in environments so unforgiving that they sometimes grow directly out of solid rock. The means of initial attachment to the stone is not known but is accomplished by a bulbous disk-like swelling of the trunk. This disk-like growth at the base of the tree prevents it from being torn away from the rock during the violent storms that frequent the region they grow in. This feature is slight or absent in trees grown in rocky soil or gravel. The tears from these hardy survivors are considered superior due to their more fragrant aroma.

The trees start producing resin when they are about 8 to 10 years old.[1] Tapping is done 2 to 3 times a year with the final taps producing the best tears due to their higher aromatic terpene, sesquiterpene and diterpene content. Generally speaking, the more opaque resins are the best quality. Dhofari frankincense (from Boswellia sacra)[1] is said to be the best in the world, although fine resin is also produced more extensively in Yemen and along the northern coast of Somalia, from which the Roman Catholic Church draws its supplies.[2]

Recent studies have indicated that frankincense tree populations are declining due to over-exploitation. Heavily tapped trees have been found to produce seeds that germinate at only 16% while seeds of trees that had not been tapped germinate at more than 80%.

History

Frankincense has been traded on the Arabian Peninsula and in North Africa for more than 5000 years.[3] A mural depicting sacks of frankincense traded from the Land of Punt adorns the walls of the temple of ancient Egyptian Queen Hatshepsut, who died in 1458 BCE.[4]

Frankincense was reintroduced to Europe by Frankish Crusaders. Although it is better known as "frankincense" to westerners, the resin is also known as olibanum, which is derived from the Arabic al-lubān (roughly translated: "that which results from milking"), a reference to the milky sap tapped from the Boswellia tree. Some have also postulated that the name comes from the Arabic term for "Oil of Lebanon" since Lebanon was the place where the resin was sold and traded with Europeans. Compare with Exodus 30:34, where it is named levonah, meaning either "white" or "Lebanese" in Hebrew.

The lost city of Ubar, sometimes identified with Irem in what is now the town of Shisr in Oman, is believed to have been a centre of the frankincense trade along the recently rediscovered "Incense Road". Ubar was rediscovered in the early 1990s and is now under archaeological excavation.

The Greek historian Herodotus was familiar with Frankincense and knew it was harvested from trees in southern Arabia. He reports, however, that the gum was dangerous to harvest because of venomous snakes that lived in the trees. He goes on to describe the method used by the Arabians to get around this problem, that being the burning of the gum of the styrax tree whose smoke would drive the snakes away.[5] The resin is also mentioned by Theophrastus and by Pliny the Elder in his Naturalis Historia.

Quality

Frankincense comes in many grades, and its quality is based on colour, purity, aroma, and age. Silver and Hojari are generally considered the highest grades of frankincense. The Omanis themselves generally consider Silver to be a better grade than Hojari, though most Western connoisseurs think that it should be the other way round. This may be due to climatic conditions with the Hojari smelling best in the relatively cold, damp climate of Europe and North America, whereas Silver may well be more suited to the hot dry conditions of Arabia.

Local market information in Oman suggests that the term Hojari encompasses a broad range of high-end frankincense including Silver. Resin value is determined not only by fragrance but also by color and clump size, with lighter color and larger clumps being more highly prized. The most valuable Hojari frankincense locally available in Oman is even more expensive than Somalia's Maydi frankincense derived from B. frereana (see below). The vast majority of this ultra-high-end B. sacra frankincense is purchased by His Majesty Sultan Qaboos bin Said the ruler of Oman, and is notoriously difficult for western buyers to correctly identify and purchase.

Uses

Frankincense is used in perfumery and aromatherapy. Olibanum essential oil is obtained by steam distillation of the dry resin. Some of the smell of the olibanum smoke is due to the products of pyrolysis.

Frankincense was lavishly used in religious rites. In the Book of Exodus in the Old Testament, it was an ingredient for incense (Ex 30:34); according to the book of Matthew 2:11, gold, frankincense, and myrrh were among the gifts to Jesus by the Biblical Magi "from out of the East."

The Egyptians ground the charred resin into a powder called kohl. Kohl was used to make the distinctive black eyeliner seen on so many figures in Egyptian art. The aroma of frankincense is said to represent life and the Judaic, Christian, and Islamic faiths have often used frankincense mixed with oils to anoint newborn infants and individuals considered to be moving into a new phase in their spiritual lives.

The growth of Christianity depressed the market for frankincense during the 4th century AD. Desertification made the caravan routes across the Rub' al Khali or "Empty Quarter" of Arabia more difficult. Additionally, increased raiding by the nomadic Parthians in the Near East caused the frankincense trade to dry up after about 300 AD.

Traditional medicine

Frankincense resin is edible and often used in various traditional medicines in Asia for digestion and healthy skin. Edible frankincense must be pure for internal consumption, meaning it should be translucent, with no black or brown impurities. It is often light yellow with a (very) slight greenish tint. It is often chewed like gum, but it is stickier because it is a resin.

In Ayurvedic medicine Indian frankincense (Boswellia serrata), commonly referred to as "dhoop," has been used for hundreds of years for treating arthritis, healing wounds, strengthening the female hormone system, and purifying the atmosphere from undesirable germs. The use of frankincense in Ayurveda is called "dhoopan". In Indian culture, it is suggested that burning frankincense everyday in house brings good health.[6]

Burning frankincense repels mosquitos and thus helps protect people and animals from mosquito-borne illnesses, such as malaria, West Nile Virus, and Dengue Fever.[7]

Frankincense essential oil

The essential oil of frankincense is produced by steam distillation of the tree resin. The oil's chemical components are 75% monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, monoterpenoles, sesquiterpenols, and ketones. It has a good balsamic and sweet fragrance, while the Indian frankincense oil has a very fresh smell.

Perfume

Olibanum is characterized by a balsamic-spicy, slightly lemon, and typical fragrance of incense, with a slightly conifer-like undertone. It is used in the perfume as well as cosmetics and pharmaceuticals industries.

Medical research

Standardized preparations of Indian frankincense from Boswellia serrata are being investigated in scientific studies as a treatment for chronic inflammatory diseases such as Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, and osteoarthritis. Initial clinical study results indicate efficacy of incense preparations for Crohn's disease. For therapy trials in ulcerative colitis, asthma, and rheumatoid arthritis there are only isolated reports and pilot studies from which there is not yet sufficient evidence of safety and efficacy. Similarly, the long-term effects and side effects of taking frankincense has not yet been scientifically investigated. Boswellic acid in vitro antiproliferative effects on various tumor cell lines (such as melanoma, glioblastomas, liver cancer) are based on induction of apoptosis. A positive effect has been found in the use of incense on the accompanying specimens of brain tumors, although in smaller clinical trials. Some scientists say the results are due to methodological flaws. The main active compound of Indian incense is viewed as being boswellic acid.

As of May 2008 FASEB Journal announced that Johns Hopkins University and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem have determined that frankincense smoke is a psychoactive drug that relieves depression and anxiety in mice.[8] The researchers found that the chemical compound incensole acetate[9] is responsible for the effects.[8]

In a different study, an enriched extract of "Indian Frankincense" (usually Boswellia serrata) was used in a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study of patients with osteoarthritis. Patients receiving the extract showed significant improvement in their arthritis in as little as seven days. The compound caused no major adverse effects and, according to the study authors, is safe for human consumption and long-term use.[10]

The study was funded by a company which produces frankincense extract,[4] and that the results have not yet been duplicated by another study.

In a study published in March 2009 by the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center it was reported that "Frankincense oil appears to distinguish cancerous from normal bladder cells and suppress cancer cell viability."[11]

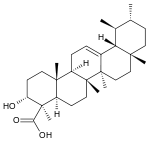

Chemical composition

These are some of the chemical compounds present in frankincense:

- "acid resin (56 per cent), soluble in alcohol and having the formula C20H32O4"[12]

- gum (similar to gum arabic) 30–36%[12]

- 3-acetyl-beta-boswellic acid (Boswellia sacra)[13]

- alpha-boswellic acid (Boswellia sacra)[13]

- 4-O-methyl-glucuronic acid (Boswellia sacra)[13]

- incensole acetate

- phellandrene[12]

See also

- Desi Sangye Gyatso

- Frankincense Trail

- Incense

- Incense Route

- Myrrh

- Nabataeans

- Pliny the Elder

- Resin

- Theophrastus

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Omani World Heritage Sites". www.omanwhs.gov.om. http://www.omanwhs.gov.om/english/Frank/FrankincenseTree.asp. Retrieved 2009-01-14.

- ↑ BBC.co.uk

- ↑ Paper on Chemical Composition of Frankincense

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Queen Hatshepsut's expedition to the Land of Punt: The first oceanographic cruise?". Dept. of Oceanography, Texas A&M University. http://ocean.tamu.edu/Quarterdeck/QD3.1/Elsayed/elsayedhatshepsut.html. Retrieved 2010-05-08.

- ↑ Herodotus 3,107

- ↑ "Joint relief". www.herbcompanion.com. http://www.herbcompanion.com/health/JOINT-RELIEF.aspx?page=2. Retrieved 2009-01-12.

- ↑ "Sultan Qaboos Cultural Center". www.sqcc.org. http://www.sqcc.org/about_oman/frankincense.htm. Retrieved 2009-01-17.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Breaking News--The FASEB Journal (07-101865)". The FASEB Journal. http://www.fasebj.org/Press_Room/07_101865_Press_Release.shtml. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- ↑ ACS.org

- ↑ "A double blind, randomized, placebo controlled study of the efficacy and safety of 5-Loxin for treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee". Arthritis Research & Therapy. http://arthritis-research.com/content/10/4/R85. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- ↑ "Frankincense oil derived from Boswellia carteri induces tumor cell specific cytotoxicity.". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19296830?dopt=Citation.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 "Olibanum.—Frankincense.". Henriette's Herbal Homepage. www.henriettesherbal.com. http://www.henriettesherbal.com/eclectic/kings/boswellia.html. Retrieved 2009-01-14.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 "Farmacy Query". www.ars-grin.gov. http://sun.ars-grin.gov:8080/npgspub/xsql/duke/plantdisp.xsql?taxon=168. Retrieved 2009-01-14.

References

- The Road to Ubar: Finding the Atlantis of the Sands — Clapp Nicholas, 1999. ISBN 0-395-95786-9.

- Frankincense & Myrrh: A Study of the Arabian Incense Trade — Groom, Nigel, 1981. ISBN 0-86685-593-9.

- Gold, Frankincense, and Myrrh: An Introduction to Eastern Christian Spirituality — Maloney George A, 1997. ISBN 0-8245-1616-8.

- Tapped-out trees threaten frankincense, Foxnews.com science (citing a study co-authored by botanists and ecologists from the Netherlands and Eritrea and published in The Journal of Applied Ecology, December 2006.)

- Frankincense Provides Relief for Osteoarthritis

External links

- Phytochemical Investigations on Boswellia Species

- Boswellia Serrata

- Omani sites on the world heritage list

Articles

- Atlantis of the Sands — Archaeology Magazine May–June 1997

- Frankincense in Oman article

- Spices Exotic Flavors and Medicines — UCLA Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library Spice Exhibit Frankincense and Myrrh 2002

- Thinkgene.com - Incense is psychoactive: Scientists identify the biology behind the ceremony. May 2008

- Scents of Place: Frankincense in Oman

Related sites

- History of Frankincense (www.itmonline.org)

- Chemical compounds found in Boswellia sacra (Dr. Duke's Databases)

- UNESCO Frankincense Trail Dhofar Province, Oman.

- Trade Between Arabia and the Empires of Rome and Asia, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Lost City of Arabia Interview with Dr. Juris Zarins, Nova, September 1996.

- Frankincense and Oman, Sultan Qaboos Cultural Center.

- The Indian Ocean in World History: Educational website Learn about the frankincense trade throughout history on this interactive website.

- Short review of recent studies about incense as medicine now and in ancient times, Short review of recent studies about incense as medicine now and in ancient times.

- Traditional Chinese medical use of frankincence