Estrogen

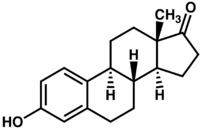

Estrogens (AmE), oestrogens (BE), or œstrogens, are a group of steroid compounds, named for their importance in the estrous cycle, and functioning as the primary female sex hormone, their name comes from estrus/oistros (period of fertility for female mammals) + gen/gonos = to generate.

Estrogens are found in all vertebrates [1]. [2]. Studies have shown that insects make use of the steroids estradiol and estriol, which are androgen and estrogen-like substances. These steroids suggest that vertebrate sex hormones have an ancient evolutionary history. [3]

Estrogens are used as part of some oral contraceptives, in estrogen replacement therapy for postmenopausal women, and in hormone replacement therapy for trans women.

Like all steroid hormones, estrogens readily diffuse across the cell membrane. Once inside the cell, they bind to and activate estrogen receptors which in turn up-regulate the expression of many genes.[4] Additionally, estrogens have been shown to activate a G protein-coupled receptor, GPR30.[5]

Contents |

Types

Steroidal

The three major naturally occurring estrogens in women are estrone (E1), estradiol (E2), and estriol (E3). Estradiol (E2) is the predominant form in nonpregnant females, estrone is produced during menopause, and estriol is the primary estrogen of pregnancy. In the body these are all produced from androgens through actions of enzymes.

- From menarche to menopause the primary estrogen is 17β-estradiol. In postmenopausal women more estrone is present than estradiol.

- Estradiol is produced from testosterone and estrone from androstenedione by aromatase.

- Estrone is weaker than estradiol.

Premarin, a commonly prescribed estrogenic drug, contains the steroidal estrogens equilin and equilenin, in addition to estrone sulfate but due to its health risk, more genetic estrogen named Progynova (estradiol valerate) are now more often prescribed.

Nonsteroidal

A range of synthetic and natural substances have been identified that also possess estrogenic activity.[6]

- Synthetic substances of this kind are known as xenoestrogens.

- Plant products with estrogenic activity are called phytoestrogens.

- Those produced by fungi are known as mycoestrogens.

Unlike estrogens produced by mammals, these substances are not necessarily steroids.

Biosynthesis

Estrogens are produced primarily by developing follicles in the ovaries, the corpus luteum, and the placenta. Luteinizing hormone (LH) stimulates the production of estrogen in the ovaries. Some estrogens are also produced in smaller amounts by other tissues such as the liver, adrenal glands, and the breasts. These secondary sources of estrogens are especially important in postmenopausal women. Fat cells also produce estrogen,[7] potentially being the reason why underweight or overweight are risk factors for infertility.[8]

In females, synthesis of estrogens starts in theca interna cells in the ovary, by the synthesis of androstenedione from cholesterol. Androstenedione is a substance of moderate androgenic activity. This compound crosses the basal membrane into the surrounding granulosa cells, where it is converted to estrone or estradiol, either immediately or through testosterone. The conversion of testosterone to estradiol, and of androstenedione to estrone, is catalyzed by the enzyme aromatase.

Estradiol levels vary through the menstrual cycle, with levels highest just before ovulation.

Function

While estrogens are present in both men and women, they are usually present at significantly higher levels in women of reproductive age. They promote the development of female secondary sexual characteristics, such as breasts, and are also involved in the thickening of the endometrium and other aspects of regulating the menstrual cycle. In males, estrogen regulates certain functions of the reproductive system important to the maturation of sperm[9][10][11] and may be necessary for a healthy libido.[12][13] Furthermore, there are several other structural changes induced by estrogen in addition to other functions. In dentistry, it reduces hyperkeratinization of the gingiva and increase vascular permeability, exudation, and edema.

- Structural

- promote formation of female secondary sex characteristics

- accelerate metabolism (burn fat)

- reduce muscle mass

- stimulate endometrial growth

- increase uterine growth

- increase vaginal lubrication

- thicken the vaginal wall

- maintenance of vessel and skin

- reduce bone resorption, increase bone formation

- morphic change (endomorphic -> mesomorphic -> ectomorphic)

- protein synthesis

- increase hepatic production of binding proteins

- coagulation

- Lipid

- increase HDL, triglyceride

- decrease LDL, fat deposition

- Fluid balance

- Gastrointestinal tract

- reduce bowel motility

- increase cholesterol in bile

- Melanin

- increase pheomelanin, reduce eumelanin

- Cancer

- support hormone-sensitive breast cancers (see section below)

- Lung function

Sexual desire is dependent on androgen levels rather than estrogen levels.[15]

Fetal development

In mice, estrogens (which are locally aromatized from androgens in the brain) play an important role in psychosexual differentiation, for example, by masculinizing territorial behavior;[16] the same is not true in humans.[17] In humans, the masculinizing effects of prenatal androgens on behavior (and other tissues, with the possible exception of effects on bone) appear to act exclusively through the androgen receptor.[18] As a result, the utility of rodent models for studying human psychosexual differentiation has been questioned.[19]

Mental health

Estrogen is considered to play a significant role in women’s mental health. Sudden estrogen withdrawal, fluctuating estrogen, and periods of sustained estrogen low levels correlates with significant mood lowering. Clinical recovery from postpartum, perimenopause, and postmenopause depression has been shown to be effective after levels of estrogen were stabilized and/or restored.[20][21]

Low estrogen levels in male lab mice may be one cause of obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD). When estrogen levels were raised through the increased activity of the enzyme aromatase in male lab mice, OCD rituals were dramatically decreased. Hypothalamic protein levels in the gene COMT are enhanced by increasing estrogen levels which is believed to return mice that displayed OCD rituals to normal activity. Aromatase deficiency is ultimately suspected which is involved in the synthesis of estrogen in humans and has therapeutic implications in humans having obsessive-compulsive disorder.[22]

Medical applications

Oral contraceptives

Since estrogen circulating in the blood can negatively feed-back to reduce circulating levels of FSH and LH, most oral contraceptives contain a synthetic estrogen, along with a synthetic progestin. Even in men, the major hormone involved in LH feedback is estradiol, not testosterone.

Hormone replacement therapy

As more fully discussed in the article on Hormone replacement therapy, estrogen and other hormones are given to postmenopausal women in order to prevent osteoporosis as well as treat the symptoms of menopause such as hot flashes, vaginal dryness, urinary stress incontinence, chilly sensations, dizziness, fatigue, irritability, and sweating. Fractures of the spine, wrist, and hips decrease by 50-70% and spinal bone density increases by ~5% in those women treated with estrogen within 3 years of the onset of menopause and for 5–10 years thereafter.

Before the specific dangers of conjugated equine estrogens were well understood, standard therapy was 0.625 mg/day of conjugated equine estrogens (such as Premarin). There are, however, risks associated with conjugated equine estrogen therapy. Among the older postmenopausal women studied as part of the Women's Health Initiative (WHI), an orally administered conjugated equine estrogen supplement was found to be associated with an increased risk of dangerous blood clotting. The WHI studies used one type of estrogen supplement, a high oral dose of conjugated equine estrogens (Premarin alone and with medroxyprogesterone acetate as PremPro).[23]

In a study by the NIH, esterified estrogens were not proven to pose the same risks to health as conjugated equine estrogens. Hormone replacement therapy has favorable effects on serum cholesterol levels, and when initiated immediately upon menopause may reduce the incidence of cardiovascular disease, although this hypothesis has yet to be tested in randomized trials. Estrogen appears to have a protector effect on atherosclerosis : it lowers LDL and triglycerides, it raises HDL levels and has endothelial vasodilatation properties plus an anti-inflammatory component.

Research is underway to determine if risks of estrogen supplement use are the same for all methods of delivery. In particular, estrogen applied topically may have a different spectrum of side-effects than when administered orally,[24] and transdermal estrogens do not affect clotting as they are absorbed directly into the systemic circulation, avoiding first-pass metabolism in the liver. This route of administration is thus preferred in women with a history of thrombo-embolic disease.

Estrogen is also used in the therapy of vaginal atrophy, hypoestrogenism (as a result of hypogonadism, castration, or primary ovarian failure), amenorrhea, dysmenorrhea, and oligomenorrhea. Estrogens can also be used to suppress lactation after child birth.

Breast cancer

About 80% of breast cancers, once established, rely on supplies of the hormone estrogen to grow: they are known as hormone-sensitive or hormone-receptor-positive cancers. Suppression of production of estrogen in the body is a treatment for these cancers.

Recently researchers have discovered that the common table mushroom has anti-aromatase[25] properties and therefore possible anti-estrogen activity. Clinical trials have begun in the United States looking into whether the table mushroom can prevent breast cancer in people.[26] A recent study has highlighted the importance of this research. In 2009, a case-control study of the eating habits of 2,018 women, revealed that women who consumed mushrooms had an approximately 50% lower incidence of breast cancer. Women who consumed mushrooms and green tea had a 90% lower incidence of breast cancer.[27]

Hormone-receptor-positive breast cancers are treated with drugs which suppress production of estrogen in the body.[28] This technique, in the context of treatment of breast cancer, is known variously as hormonal therapy, hormone therapy, or anti-estrogen therapy (not to be confused with hormone replacement therapy). Certain foods such as soy may also suppress the proliferative effects of estrogen and are used as an alternative to hormone therapy.[29]

Prostate cancer

Under certain circumstances, estrogen may also be used in males for treatment of prostate cancer.[30]

Miscellaneous

In humans and mice, estrogen promotes wound healing.[31]

At one time, estrogen was used to induce growth attenuation in tall girls.[32] Recently, estrogen-induced growth attenuation was used as part of the controversial Ashley Treatment to keep a developmentally disabled girl from growing to adult size.[33]

Most recently, estrogen has been used in experimental research as a way to treat patients suffering from bulimia nervosa, in addition to Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, which is the established standard for treatment in bulimia cases. The estrogen research hypothesizes that the disease may be linked to a hormonal imbalance in the brain.[34]

Estrogen has also been used in studies which indicate that it may be an effective drug for use in the treatment of traumatic liver injury.[35]

Health risks and warning labels

Hyperestrogenemia (elevated levels of estrogen) may be a result of exogenous administration of estrogen or estrogen-like substances, or may be a result of physiologic conditions such as pregnancy. Any of these causes is linked with an increase in the risk of thrombosis.[36]

The labeling of estrogen-only products in the U.S. includes a boxed warning that unopposed estrogen (without progestagen) therapy increases the risk of endometrial cancer.

Based on a review of data from the WHI, on January 8, 2003 the FDA changed the labeling of all estrogen and estrogen with progestin products for use by postmenopausal women to include a new boxed warning about cardiovascular and other risks. The estrogen-alone substudy of the WHI reported an increased risk of stroke and deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in postmenopausal women 50 years of age or older and an increased risk of dementia in postmenopausal women 65 years of age or older using 0.625 mg of Premarin conjugated equine estrogens (CEE). The estrogen-plus-progestin substudy of the WHI reported an increased risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, invasive breast cancer, pulmonary emboli and DVT in postmenopausal women 50 years of age or older and an increased risk of dementia in postmenopausal women 65 years of age or older using PremPro, which is 0.625 mg of CEE with 2.5 mg of the progestin medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA).[37][38][39]

Cosmetics

Some hair shampoos on the market include estrogens and placental extracts; others contain phytoestrogens. There are case reports of young children developing breasts after exposure to these shampoos.[40] On September 9, 1993, the FDA determined that not all topically applied hormone-containing drug products for OTC human use are generally recognized as safe and effective and are misbranded. An accompanying proposed rule deals with cosmetics, concluding that any use of natural estrogens in a cosmetic product makes the product an unapproved new drug and that any cosmetic using the term "hormone" in the text of its labeling or in its ingredient statement makes an implied drug claim, subjecting such a product to regulatory action.[41]

In addition to being considered misbranded drugs, products claiming to contain placental extract may also be deemed to be misbranded cosmetics if the extract has been prepared from placentas from which the hormones and other biologically active substances have been removed and the extracted substance consists principally of protein. The FDA recommends that this substance be identified by a name other than "placental extract" and describing its composition more accurately because consumers associate the name "placental extract" with a therapeutic use of some biological activity.[41]

History

In 1929 Adolf Butenandt and Edward Adelbert Doisy independently isolated and determined the structure of estrogen.[42] Thereafter, the market for hormonal drug research opened up.

The “first orally effective estrogen”, Emmenin, derived from the late-pregnancy urine of Canadian women, was introduced in 1930 by Collip and Ayerst Laboratories. Estrogens are not water-soluble and cannot be given orally, but the urine was found to contain estriol glucuronide which is water soluble and becomes active in the body after hydrolization.

Scientists continued to search for new sources of estrogen because of concerns associated with the practicality of introducing the drug into the market. At the same time, a German pharmaceutical drug company, formulated a similar product as Emmenin that was introduced to German women to treat menopausal symptoms.

In 1938, British scientists obtained a patent on a newly formulated nonsteroidal estrogen, diethylstilbestrol (DES), that was cheaper and more powerful than the previously manufactured estrogens. Soon after, concerns over the side effects of DES were raised in scientific journals while the drug manufacturers came together to lobby for governmental approval of DES. It was only until 1941 when estrogen therapy was finally approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of menopausal symptoms.[43]

Environmental effects

In recent years it has been found that through waste water removal, estrogen has made its way into our ecosystems. Estrogen is among the wide range of endocrine-disrupting compounds (EDCs) due to the fact that they have high estrogenic potency. When this specific EDC makes its way into the environment it can cause severe male reproductive dysfunction to both humans and wildlife.[44] The estrogen excreted from women as well as the estrogen that remains in the waste of birth control pills makes its way into fresh water systems. During the germination period of reproduction the fish are exposed to low levels of estrogen which cause reproductive dysfunction to male fish.[45] Some male fish end up becoming "intersex", containing both male and female parts. Other fish may only suffer from low fertility or sperm count. This is putting a great strain on our ecosystems as entire populations of fish are slowly being eliminated, due to an inability for some fish to reproduce.[46]

See also

- List of steroid abbreviations

- Diethylstilbestrol

- Atrophic vaginitis

- Endocrinology

- Equol

- Equilin

- Estradiol

- Estrogen receptor

- Progesterone

- Progestin

- Testosterone

- Endocrine disruptor

References

- ↑ http://www.springerlink.com/content/m5t4612215x2755x/

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17368538

- ↑ http://www.springerlink.com/content/tr77034552r222m1/

- ↑ Whitehead SA, Nussey S (2001). Endocrinology: an integrated approach. Oxford: BIOS: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 1-85996-252-1. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/bv.fcgi?call=bv.View..ShowTOC&rid=endocrin.TOC&depth=10.

- ↑ Prossnitz ER, Arterburn JB, Sklar LA (2007). "GPR30: A G protein-coupled receptor for estrogen". Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 265-266: 138–42. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2006.12.010. PMID 17222505.

- ↑ Fang H, Tong W, Shi LM, Blair R, Perkins R, Branham W, Hass BS, Xie Q, Dial SL, Moland CL, Sheehan DM (2001). "Structure-activity relationships for a large diverse set of natural, synthetic, and environmental estrogens". Chem. Res. Toxicol. 14 (3): 280–94. doi:10.1021/tx000208y. PMID 11258977.

- ↑ Nelson LR, Bulun SE (September 2001). "Estrogen production and action". J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 45 (3 Suppl): S116–24. PMID 11511861.

- ↑ FERTILITY FACT > Female Risks By the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM). Retrieved on Jan 4, 2009

- ↑ Hess RA, Bunick D, Lee KH, Bahr J, Taylor JA, Korach KS, Lubahn DB (1997). "A role for oestrogens in the male reproductive system". Nature 390 (6659): 447–8. doi:10.1038/37352. PMID 9393999.

- ↑ J. Raloff (1997-12-06). "Science News Online (12/6/97): Estrogen's Emerging Manly Alter Ego". Science News. http://www.sciencenews.org/pages/sn_arc97/12_6_97/fob1.htm. Retrieved 2008-03-04.

- ↑ "Science Blog -- Estrogen Linked To Sperm Count, Male Fertility". Science Blog. http://www.scienceblog.com/community/older/1997/B/199701564.html. Retrieved 2008-03-04.

- ↑ Hill RA, Pompolo S, Jones ME, Simpson ER, Boon WC (2004). "Estrogen deficiency leads to apoptosis in dopaminergic neurons in the medial preoptic area and arcuate nucleus of male mice". Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 27 (4): 466–76. doi:10.1016/j.mcn.2004.04.012. PMID 15555924.

- ↑ Ian Muchamore (2004-07-19). "Prince Henry's Institute - Media Release - Male sex drive linked to estrogen". Prince Henry's Institute. http://www.phimr.monash.edu.au/news/media_releases/estrogen_vital_for_male_sex_drive.htm. Retrieved 2008-03-04.

- ↑ Massaro D, Massaro GD (December 2004). "Estrogen regulates pulmonary alveolar formation, loss, and regeneration in mice". Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 287 (6): L1154–9. doi:10.1152/ajplung.00228.2004. PMID 15298854.

- ↑ Warnock JK, Swanson SG, Borel RW, Zipfel LM, Brennan JJ (2005). "Combined esterified estrogens and methyltestosterone versus esterified estrogens alone in the treatment of loss of sexual interest in surgically menopausal women". Menopause 12 (4): 359–60. doi:10.1097/01.GME.0000153933.50860.FD. PMID 16037752.

- ↑ Wu MV, Manoli DS, Fraser EJ, Coats JK, Tollkuhn J, Honda S, Harada N, Shah NM (October 2009). "Estrogen masculinizes neural pathways and sex-specific behaviors". Cell 139 (1): 61–72. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.036. PMID 19804754.

- ↑ Rochira V, Carani C (October 2009). "Aromatase deficiency in men: a clinical perspective". Nat Rev Endocrinol 5 (10): 559–68. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2009.176. PMID 19707181.

- ↑ Wilson JD (September 2001). "Androgens, androgen receptors, and male gender role behavior". Horm Behav 40 (2): 358–66. doi:10.1006/hbeh.2001.1684. PMID 11534997.

- ↑ Baum MJ (November 2006). "Mammalian animal models of psychosexual differentiation: when is 'translation' to the human situation possible?". Horm Behav 50 (4): 579–88. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.06.003. PMID 16876166.

- ↑ Douma, S.L, Husband, C., O’Donnell, M.E., Barwin, B.N., Woodend A.K. (2005). "Estrogen-related Mood Disorders Reproductive Life Cycle Factors". Advances in Nursing Science 28 (4): 364–375. PMID 16292022.

- ↑ Lasiuk, GC and Hegadoren, KM (2007). "The Effects of Estradiol on Central Serotonergic Systems and Its Relationship to Mood in Women". Biological Research for Nursing (2007), 9 (2): 147–160. doi:10.1177/1099800407305600. PMID 17909167.

- ↑ Hill, Rachel A., McLnnes, Kerry J., Cong, Emily C.H., Jones, Margaret E.E., Simpson, Evan R. (2007). "Estrogen deficient male mice develop Compulsive Behavior". Biological Psychiatry 61 (3): 359. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.01.012. PMID 16566897.

- ↑ "NIH - Menopausal Hormone Therapy Information". National Institutes of Health. 2007-08-27. http://www.nih.gov/PHTindex.htm. Retrieved 2008-03-04.

- ↑ Menon DV, Vongpatanasin W (2006). "Effects of transdermal estrogen replacement therapy on cardiovascular risk factors". Treat Endocrinol 5 (1): 37–51. doi:10.2165/00024677-200605010-00005. PMID 16396517.

- ↑ Chen, S., Y.C. Kao (1997). "Binding characteristics of aromatase inhibitors and phytoestrogens to human aromatase.". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (City of Hope, Duarte, California) 61 (3-6): 107–115. PMID 9365179

- ↑ . http://www.cityofhope.org/about/publications/eHope/2008-vol-7-num-7-july-29/Pages/a-salad-fixin-with-medical-benefits.aspx.

- ↑ Zhang, M; Huang, J; Xie, X; Holman, CD (2009). "Dietary intakes of mushrooms and green tea combine to reduce the risk of breast cancer in Chinese women.". International Journal of Cancer (International Journal of Cancer (Online)) 124 (6): 1404–1408. doi:10.1002/ijc.24047. PMID 19048616

- ↑ "Hormonal Therapy". breastcancer.org. 2007-07-26. http://www.breastcancer.org/tre_sys_hrt_idx.html. Retrieved 2008-03-04.

- ↑ Kurzer MS (2002). "Hormonal effects of soy in premenopausal women and men". J. Nutr. 132 (3): 570S–573S. PMID 11880595. http://jn.nutrition.org/cgi/content/abstract/132/3/570S.

- ↑ Oh WK (2002). "The evolving role of estrogen therapy in prostate cancer" (– search). Clin Genitourinary Cancer 1 (2): 81–9. PMID 15046698. http://www.cigjournals.com/CIG/c.abs/clinical-genitourinary-cancer/volume1/issue2/article792.

- ↑ Oh DM, Phillips, TJ (2006). "Sex Hormones and Wound Healing". Wounds 18 (1): 8–18. http://www.woundsresearch.com/article/5190.

- ↑ Lee JM, Howell JD (2006). "Tall girls: the social shaping of a medical therapy". Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 160 (10): 1077–8. doi:10.1001/archpedi.160.10.1035. PMID 17018462.

- ↑ Gunther DF, Diekema DS (2006). "Attenuating growth in children with profound developmental disability: a new approach to an old dilemma". Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 160 (10): 1013–7. doi:10.1001/archpedi.160.10.1013. PMID 17018459.

- ↑ Gunilla Andersson (2007-01-09). "Bulimia May Result from Hormonal Imbalance". Karolinska Institutet. http://ki.se/ki/jsp/polopoly.jsp?d=130&a=22684&l=en&newsdep=130. Retrieved 2008-03-04.

- ↑ Hsieh YC, Yu HP, Frink M, Suzuki T, Choudhry MA, Schwacha MG, Chaudry IH (2007). "G protein-coupled receptor 30-dependent protein kinase A pathway is critical in nongenomic effects of estrogen in attenuating liver injury after trauma-hemorrhage". Am. J. Pathol. 170 (4): 1210–8. doi:10.2353/ajpath.2007.060883. PMID 17392161.

- ↑ Chapter 4 in: Mitchell, Richard Sheppard; Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology: With STUDENT CONSULT Online Access. Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 1-4160-2973-7. 8th edition.

- ↑ FDA (2003, January 8). "FDA Approves New Labels for Estrogen and Estrogen with Progestin Therapies for Postmenopausal Women Following Review of Women's Health Initiative Data". http://web.archive.org/web/20071221093608/http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/NEWS/2003/NEW00863.html. Retrieved 2006-10-26.

- ↑ Kolata, Gina (2003, January 9). "F.D.A. Orders Warning on All Estrogen Labels". The New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?sec=health&res=9C00E0DD103EF93AA35752C0A9659C8B63. Retrieved 2006-10-26.

- ↑ NLM (2006, April 1). "IMPORTANT WARNING". Drug Information: Estrogen. MedlinePlus. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/druginfo/medmaster/a682922.html. Retrieved 2006-10-26.

- ↑ Sanghavi, DM (October 17, 2006). "Preschool Puberty, and a Search for the Causes". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/17/science/17puberty.html. Retrieved 2008-06-04

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 FDA (1995, February). "Products containing estrogenic hormones, placental extract or vitamins". Guide to Inspections of Cosmetic Product Manufacturers. http://web.archive.org/web/20071014014542/http://www.fda.gov/ora/inspect_ref/igs/cosmet.html. Retrieved 2006-10-24.

- ↑ Tata JR (2005). "One hundred years of hormones". EMBO Rep. 6 (6): 490–6. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400444. PMID 15940278.

- ↑ Rothenberg, Carla J. (2005-04-25). "The Rise and Fall of Estrogen Therapy: The History of HRT" (PDF). http://leda.law.harvard.edu/leda/data/711/Rothenberg05.pdf. Retrieved 2006-10-27.

- ↑ Wang S, Huang W, Fang G, Zhang Y, Qiao H (2008). "Analysis of steroidal estrogen residues in food and environmental samples". International Journal of Environmental Analytical Chemistry 88 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1080/03067310701597293.

- ↑ Liney KE, Jobling S, Shears JA, Simpson P, Tyler CR (October 2005). "Assessing the sensitivity of different life stages for sexual disruption in roach (Rutilus rutilus) exposed to effluents from wastewater treatment works". Environ. Health Perspect. 113 (10): 1299–307. PMID 16203238.

- ↑ Jobling S, Williams R, Johnson A, Taylor A, Gross-Sorokin M, Nolan M, Tyler CR, van Aerle R, Santos E, Brighty G (April 2006). "Predicted exposures to steroid estrogens in U.K. rivers correlate with widespread sexual disruption in wild fish populations". Environ. Health Perspect. 114 Suppl 1: 32–9. PMID 16818244.

External links and further reading

- It's wise to be wary of the pill

- MedlinePlus DrugInfo medmaster-a682922

- Nussey and Whitehead: Endocrinology, an integrated approach, Taylor and Francis 2001. Free online textbook.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||