Esophagus

| Esophagus | |

|---|---|

|

|

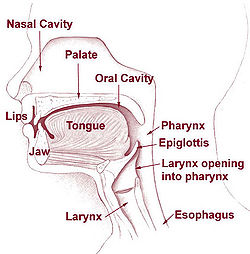

| Head and neck. | |

|

|

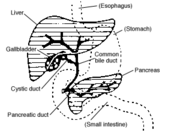

| Digestive organs. (Esophagus is #1) | |

| Latin | œsophagus |

| Gray's | subject #245 1144 |

| Artery | esophageal arteries |

| Vein | esophageal veins |

| Nerve | celiac ganglia, vagus[1] |

| Precursor | Foregut |

| MeSH | oesophagus |

| Dorlands/Elsevier | Esophagus |

The esophagus or oesophagus (see spelling differences), sometimes known as the gullet, is an organ in vertebrates which consists of a muscular tube through which food passes from the pharynx to the stomach. During swallowing food passes from the mouth through the pharynx into the esophagus and travels via peristalsis to the stomach. The word esophagus is derived from the Latin œsophagus, which derives from the Greek word oisophagos , lit. "entrance for eating." In humans the esophagus is continuous with the laryngeal part of the pharynx at the level of the C6 vertebra. The esophagus passes through a hole in the diaphragm at the level of the tenth thoracic vertebrae (T10). It is usually about 25–30 cm long and connects the mouth to the stomach. It is divided into cervical, thoracic and abdominal parts.

Contents |

Histology

The layers of the esophagus are as follows:[2]

- mucosa (mucus)

- nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium: is rapidly turned over, and serves a protective effect due to the high volume transit of food, saliva and mucus.

- lamina propria: sparse.

- muscularis mucosae: smooth muscle

- submucosa: Contains the mucous secreting glands (esophageal glands), and connective structures termed papillae.

- muscularis externa (or "muscularis propria"): composition varies in different parts of the esophagus, to correspond with the conscious control over swallowing in the upper portions and the autonomic control in the lower portions:

- upper third, or superior part: striated muscle

- middle third, smooth muscle and striated muscle

- inferior third: predominantly smooth muscle

- adventitia

Constrictions of esophagus

Normally the esophagus shows four constrictions at the following levels.

- At its beginning,15cm from the incisor teeth.

- Where it is crossed by the aortic arch, 22.5 cm from the incisor teeth.

- Where it is crossed by the left bronchus, 27.5 cm from the incisor teeth.

- Where it pierces the diaphragm, 37.5 cm from the incisor teeth.

The distances from the incisor teeth are important in passing instruments into the esophagus.

Gastroesophageal junction

The junction between the esophagus and the stomach (the gastroesophageal junction or GE junction) is not actually considered a valve, although it is sometimes called the cardiac sphincter, cardia or cardias, although it is actually better resembles a structure.

In much of the gastrointestinal tract, smooth muscles contract in sequence to produce a peristaltic wave which forces a ball of food (called a bolus) while in the esophagus. In humans, peristalsis is found in the contraction of smooth muscles to propel contents through the digestive tract.

In other animals

In most fish, the esophagus is extremely short, primarily due to the length of the pharynx (which is associated with the gills). However, some fish, including lampreys, chimaeras, and lungfish, have no true stomach, so that the oesophagus effectively runs from the pharynx directly to the intestine, and is therefore somewhat longer.[3]

In tetrapods, the pharynx is much shorter, and the esophagus correspondingly longer, than in fish. In amphibians, sharks and rays, the esophageal epithelium is ciliated, helping to wash food along, in addition to the action of muscular peristalsis. In the majority of vertebrates, the esophagus is simply a connecting tube, but in birds, it is extended towards the lower end to form a crop for storing food before it enters the true stomach.[3]

A structure with the same name is often found in invertebrates, including molluscs and arthropods, connecting the oral cavity with the stomach

See also

- Esophageal disease

Additional images

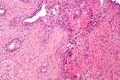

H&E stain of biopsy of normal esophagus showing the stratified squamous cell epithelium |

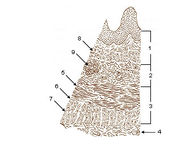

Layers of the esophagus. |

Mid-esophageal mass |

Stomach |

Accessory digestive system. |

Organs of the digestive tract. |

Esophagus |

Section of the neck at about the level of the sixth cervical vertebra. |

Transverse section of thorax, showing relations of pulmonary artery. |

Sagittal section of nose mouth, pharynx, and larynx. |

The position and relation of the esophagus in the cervical region and in the posterior mediastinum. Seen from behind. | |

Section of the human esophagus. Moderately magnified. |

|

Microscopic shot of a cross section of human gastroesophageal junction wall. |

Micrograph of herpes esophagitis. H&E stain. |

References

- ↑ Physiology at MCG 6/6ch2/s6ch2_30

- ↑ Histology at BU 10801loa

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 344–345. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||