Oedipus

| Topics in Greek mythology |

|---|

|

|

|

Oedipus (pronounced /ˈɛdɨpəs/ in American English and /ˈiːdɨpəs/ in British English; Greek: Οἰδίπους Oidípous meaning "swollen-footed") was a mythical Greek king of Thebes. He fulfilled a prophecy that said he would kill his father and marry his mother, and thus brought disaster on his city and family. This legend has been retold in many versions, and was used by Sigmund Freud to name the Oedipus complex, sometimes called the Oedipesian Paradox.

Contents |

Basics of myth

Oedipus was the son of Laius and Jocasta, king and queen of Thebes. After having been married some time without children, his parents consulted the Oracle of Apollo at Delphi about their childlessness. The Oracle prophesied that if Laius should have a son, the son would kill him and marry Jocasta. In an attempt to prevent this prophecy's fulfillment, when Jocasta indeed bore a son, Laius had his ankles pinned together so that he could not crawl, and gave the boy to a servant to abandon ("expose") on the nearby mountain. However, rather than leave the child to die of exposure, as Laius intended, the sympathetic servant passed the baby onto a shepherd from Corinth.

Oedipus the infant eventually comes to the house of Polybus, king of Corinth and his queen, Merope, who adopt him as they are without children of their own. Little Oedipus/Oidipous is named after the swelling from the injuries to his feet and ankles. The word oedema (English) or edema (American English) is from this same Greek word for swelling: οἴδημα, or oedēma.

Many years later, Oedipus is told by a drunk that Polybus is not his real father but when he asks his parents, they deny it. Oedipus seeks counsel from the same Delphic Oracle. The Oracle does not tell him the identity of his true parents but instead tells him that he is destined to kill his father and marry his mother. In his attempt to avoid the fate predicted by the Oracle, he decides to not return home to Corinth. Since it is near to Delphi, Oedipus decides to go to Thebes.

As Oedipus travels he comes to the place where three roads meet, Davlia. Here he encounters a chariot, driven by his (unrecognized) birth-father, King Laius. They fight over who has the right to go first and Oedipus kills Laius in self defense, unwittingly fulfilling part of the prophecy. The only witness of the king's death was a slave who fled from a caravan of slaves also travelling on the road.

Continuing his journey to Thebes, Oedipus encounters a Sphinx which would stop all those who traveled to Thebes and ask them a riddle. If the travellers were unable to answer correctly, they were eaten by the sphinx; if they were successful, they would be able to continue their journey. The riddle was: "What walks on four feet in the morning, two in the afternoon and three at night?". Oedipus answers: "Man; as an infant, he crawls on all fours, as an adult, he walks on two legs and, in old age, he relies on a walking stick". Oedipus was the first to answer the riddle correctly. Having heard Oedipus' answer, the Sphinx is astounded and inexplicably kills itself, freeing Thebes.

Grateful, the people of Thebes appoint Oedipus as their king and give him the recently widowed Queen Jocasta's hand in marriage. (The people of Thebes believed her husband had been killed while on a search for the answer to the Sphinx's riddle. They had no idea who the killer was.) The marriage of Oedipus and Jocasta fulfilled the rest of the prophecy. Oedipus and Jocasta have four children: two sons, Polynices and Eteocles (see Seven Against Thebes), and two daughters, Antigone and Ismene.

Many years after the marriage of Oedipus and Jocasta, a plague of infertility strikes the city of Thebes; crops no longer grow to harvest and women do not bear children. Oedipus, in his hubris, asserts that he will end the pestilence. He sends Creon, Jocasta's brother, to the Oracle at Delphi, seeking guidance. When Creon returns, Oedipus hears that the murderer of the former King Laius must be found and either be killed or exiled. In a search for the identity of the killer, Oedipus follows Creon's suggestion and sends for the blind prophet, Tiresias, who warns him not to try to find the killer. In a heated exchange, Tiresias is provoked into exposing Oedipus himself as the killer, and the fact that Oedipus is living in shame because he does not know who his true parents are. Oedipus blames Creon for Tiresias telling Oedipus that he was the killer. Oedipus and Creon begin a heated argument. Jocasta enters and tries to calm Oedipus. She tries to comfort him by telling him about her old husband and his supposed death. Oedipus becomes unnerved as he begins to think that he might have killed Laius and so brought about the plague. Suddenly, a messenger arrives from Corinth with the news that King Polybus has died and that the people of Corinth would have Oedipus as their king. Oedipus is relieved concerning the prophecy, for it could no longer be fulfilled if Polybus, whom he thinks is his father, is now dead.

Nonetheless, he is wary while his mother lives and does not wish to go. To ease the stress of the matter, the messenger then reveals that Oedipus was, in fact, adopted. Jocasta, finally realizing Oedipus' true identity, begs him to abandon his search for Laius' murderer. Oedipus misunderstands the motivation of her pleas, thinking that she was ashamed of him because he might have been the son of a slave. She then goes into the palace where she hangs herself. Oedipus seeks verification of the messenger's story from the very same herdsman who was supposed to have left Oedipus to die as a baby. From the herdsman, Oedipus learns that the infant raised as the adopted son of Polybus and Merope was the son of Laius and Jocasta. Thus, Oedipus finally realizes in great agony that so many years ago, at the place where three roads meet, he had killed his own father, King Laius, and as a consequence, married his mother, Jocasta.

Oedipus goes in search of Jocasta and finds she has killed herself. Taking two pins from her dress, Oedipus gouges his eyes out. Oedipus asks Creon to look after his daughters, for his sons are old and mature enough to look after themselves, and to be allowed to touch them one last time before he is exiled. His daughter Antigone acts as his guide as he wanders blindly through the country, ultimately dying at Colonus after being placed under the protection of Athens by King Theseus.

His two sons, Eteocles and Polynices, arrange to share the kingdom, each taking an alternating one-year reign. However, Eteocles refuses to cede his throne after his year as king. Polynices brings in an army to oust Eteocles from his position, and a battle ensues. At the end of the battle, the brothers kill each other. Jocasta's brother, Creon, takes the throne. He decides that Polynices was a "traitor," and should not be given burial rites. Defying this edict, Antigone attempts to bury her brother and, for this trespass, Creon has her buried in a rock cavern where she hangs herself.

There are many different endings to the legend of Oedipus due to its oral tradition. Significant variations on the legend of Oedipus are mentioned in fragments by several ancient Greek poets including Homer, Hesiod and Pindar. Most of what is known of Oedipus comes from the set of Theban plays by Sophocles: Oedipus the King, Oedipus at Colonus, and Antigone.

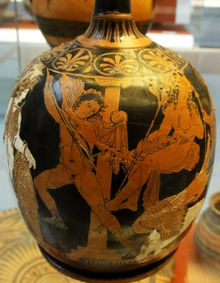

5th century BC

Oedipus slaying the sphinx |

|

| Material | Pottery, gold |

|---|---|

| Created | 420BC-400BC |

| Period/culture | Attic |

| Place | Polis-tis-Chrysokhou, tomb, Athens |

| Present location | Room 72, British Museum |

| Identification | 1887,0801.46 |

Most writing on Oedipus comes from the 5th century BC, though the stories deal mostly with Oedipus' downfall. Various details appeared on how Oedipus rose to power.

Laius heard of a prophecy that his son will kill him.[1] Fearing the prophecy, Laius pierces Oedipus' feet and leaves him out to die, but a herdsman finds him and takes him away from Thebes.[2] Oedipus, not knowing he was adopted, leaves home in fear of the same prophecy that he would kill his father and marry his mother.[3] Laius, meanwhile, ventures out to find a solution to the Sphinx's riddle.[4] As prophesized, Oedipus crossed paths with Laius and this leads to a fight where Oedipus slays Laius.[5] Oedipus then defeats the Sphinx by solving a mysterious riddle to become king.[6] He marries the widow queen Jocasta not knowing she is his mother. A plague falls on the people of Thebes. Upon discovery of the truth, Oedipus blinds himself and Jocasta hangs herself.[7] After Oedipus is no longer king, Oedipus' sons kill each other.

Some differences with older stories emerge. The curse of the Oedipus' sons is expanded backward to include Oedipus and his father, Laius. Oedipus now steps down from the throne instead of dying in battle. Additionally, rather than his children being by a second wife, Oedipus' children are now by Jocasta.

Pindar's Second Olympian Ode

In the Second Olympians Ode Pindar wrote: Laius' tragic son, crossing his father's path, killed him and fulfilled the oracle spoken of old at Pytho. And sharp-eyed Erinys saw and slew his warlike children at each other's hands. Yet Thersandros survived fallen Polyneikes and won honor in youthful contests and the brunt of war, a scion of aid to the house of Adrastos..[8]

Aeschylus' Oedipus trilogy

In 467 BC the Athenian playwright, Aeschylus, is known to have presented an entire trilogy based upon the Oedipus myth, winning the first prize at the City Dionysia. The First play was Laius, the second was Oedipus, and the third was Seven against Thebes. Only the third play survives, in which Oedipus' sons Eteocles and Polynices kill each other warring over the throne. Much like his Oresteia, this trilogy would have detailed the tribulations of a House over three successive generations. The satyr play that followed the trilogy was called the Sphinx.

Sophocles' Oedipus the King

As Sophocles' Oedipus the King begins, the people of Thebes are begging the king for help, begging him to discover the cause of the plague. Oedipus stands before them and swears to find the root of their suffering and to end it. Just then, Creon returns to Thebes from a visit to the oracle. Apollo has made it known that Thebes is harboring a terrible abomination and that the plague will only be lifted when the true murderer of old King Laius is discovered and punished for his crime. Oedipus swears to do this, not realizing of course that he himself is the abomination that he has sworn to exorcise. The stark truth emerges slowly over the course of the play, as Oedipus clashes with the blind seer Tiresias, who senses the truth. Oedipus remains in strict denial, though, becoming convinced that Tiresias is somehow plotting with Creon to usurp the throne.

Realization begins to slowly dawn in Scene II of the play when Jocasta mentions out of hand that Laius was slain at a place where three roads meet. This stirs something in Oedipus' memory and he suddenly remembers the men that he fought and killed one day long ago at a place where three roads met. He realizes, horrified, that he might be the man he's seeking. One household servant survived the attack and now lives out his old age in a frontier district of Thebes. Oedipus sends immediately for the man to either confirm or deny his guilt. At the very worst, though, he expects to find himself to be the unsuspecting murderer of a man unknown to him. The truth has not yet been made clear.

The moment of epiphany comes late in the play. At the beginning of Scene III, Oedipus is still waiting for the servant to be brought into the city, when a messenger arrives from Corinth to declare the King Polybus is dead. Oedipus, when he hears this news is overwhelmed with relief, because he believed that Polybus was the father whom the oracle had destined him to murder, and he momentarily believes himself to have escaped fate. He tells this all to the present company, including the messenger, but the messenger knows that it is not true. He is the man who found Oedipus as a baby in the pass of Kithairon and gave him to King Polybus to raise. He reveals, furthermore that the servant who is being brought to the city as they speak is the very same man who took Oedipus up into the mountains as a baby. Jocasta realizes now all that has happened. She begs Oedipus not to pursue the matter further. He refuses, and she withdraws into the palace as the servant is arriving. The old man arrives, and it is clear at once that he knows everything. At the behest of Oedipus, he tells it all.

Overwhelmed with the knowledge of all his crimes, Oedipus rushes into the palace, where he finds his mother, his wife, dead by her own hand. Ripping a brooch from her dress, Oedipus blinds himself with it. Bleeding from the eyes, he begs Creon, who has just arrived on the scene, to exile him forever from Thebes. Creon agrees to this request, Oedipus begs to hold his two daughters Antigone and Ismene with his hands one more time to have their fill of tears and Creon out of pity sends the girls in to see Oedipus one more time.

Sophocles' Oedipus at Colonus

In Sophocles' Oedipus at Colonus, Oedipus becomes a wanderer, pursued by Creon and his men. He finally finds refuge at the holy wilderness right outside of Athens, where it is said that Theseus took care of the two of them, Oedipus and his daughter, Antigone. Creon eventually catches up to Oedipus. He asks Oedipus to come back from Colonus to bless his son, Eteocles. Angry that his son did not love him enough to take care of him, he curses both Eteocles and his brother, condemning both to sudden deaths. Oedipus dies a peaceful death; his grave is said to be sacred to the gods.

Sophocles' Antigone

In Sophocles' Antigone, when Oedipus stepped down as king of Thebes, he gave the kingdom to his two sons, Eteocles and Polynices, both of whom agreed to alternate the throne every year. However, they showed no concern for their father, who cursed them for their negligence. After the first year, Eteocles refused to step down and Polynices attacked Thebes with his supporters (as portrayed in the Seven Against Thebes by Aeschylus and the Phoenician Women by Euripides). Both brothers died in the battle. King Creon, who ascended to the throne of Thebes, decreed that Polynices was not to be buried. Antigone, Polynices' sister, defied the order, but was caught. Creon decreed that she was to be put into a stone box in the ground, this in spite of her betrothal to his son Haemon. Antigone's sister, Ismene, then declared she had aided Antigone and wanted the same fate. The gods, through the blind prophet Tiresias, expressed their disapproval of Creon's decision, which convinced him to rescind his order, and he went to bury Polynices himself. However, Antigone had already hanged herself rather than be buried alive. When Creon arrived at the tomb where she was to be interred, Haemon attacked him and then killed himself. When Creon's wife, Eurydice, was informed of their deaths, she too took her own life.

Euripides' Phoenissae and Chrysippus

In the beginning of Euripides' Phoenissae, Jocasta recalls the story of Oedipus. Generally, the play weaves together the plots of the Seven Against Thebes and Antigone. The play differs from the other tales in two major respects. First, it describes in detail why Laius and Oedipus had a feud: Laius ordered Oedipus out of the road so his chariot could pass, but proud Oedipus refused to move. Second, in the play Jocasta has not killed herself at the discovery of her incest - otherwise she could not play the prologue, for fathomable reasons - nor has Oedipus fled into exile, but they have stayed in Thebes only to delay their doom until the fatal duel of their sons/brothers/nephews Eteocles and Polynices: Jocasta commits suicide over the two men's dead bodies, and Antigone follows Oedipus into exile.

In Chrysippus, Euripides develops backstory on the curse: Laius' "sin" was to have kidnapped Chrysippus, Pelops' son, in order to violate him, and this caused the gods' revenge on all his family - boy-loving having been so far an exclusive of the gods themselves, unknown to mortals.

Euripides wrote also an "Oedipus", of which only a few fragments survive.[9] The first line of the prologue recalled Laius' hybristic action of conceiving a son against Apollo's command. At some point in the action of the play, a character engaged in a lengthy and detailed description of the Sphinx and her riddle - preserved in five fragments from Oxyrhynchus, P.Oxy. 2459 (published by Eric Gardner Turner in 1962)[10]. The tragedy featured also many moral maxims on the theme of marriage, preserved in the Anthologion of Stobaeus. The most striking lines, however, state that in this play Oedipus was blinded by Laius' attendants, and that this happened before his identity as Laius' son had been discovered, therefore marking important differences with the Sophoclean treatment of the myth, which is now regarded as the 'standard' version. Many attempts have been made to reconstruct the plot of the play, but none of them is more than hypothetical, because of the scanty remains that survive from its text and of the total absence of ancient descriptions or résumés - though it has been suggested that a part of Hyginus' narration of the Oedipus myth might in fact derive from Euripides' play. Some echoes of the Euripidean Oedipus have been traced also in a scene of Seneca's Oedipus (see below), in which Oedipus himself describes to Jocasta his adventure with the Sphinx.[11]

Later additions

In the 2nd century BC, Apollodorus writes down an actual riddle for the Sphinx while borrowing the poetry of Hesiod:

What is that which has one voice and yet becomes four-footed and two-footed and three-footed?[12]

Later Addition to Aeschylus' Seven against Thebes

Due to the popularity of Sophocles's Antigone (c. 442 BC), the ending (lines 1005-78) of Seven against Thebes was added some fifty years after Aeschylus' death.[13] Whereas the play (and the trilogy of which it is the last play) was meant to end with somber mourning for the dead brothers, the spurious ending features a herald announcing the prohibition against burying Polyneices, and Antigone's declaration that she will defy that edict

Oedipus in post-Classical literature

Oedipus was a figure who was also used in the Latin literature of ancient Rome. Julius Caesar wrote a play on Oedipus, but it has not survived into modern times.[14] Ovid included Oedipus in Metamorphoses, but only as the person who defeated the Sphinx. He makes no mention of Oedipus' troubled experiences with his father and mother. Seneca the Younger wrote his own play on the story of Oedipus in the first century AD. It differs in significant ways from the work of Sophocles.

Seneca's play on the myth was intended to be recited at private gatherings and not actually performed. It has however been successfully staged since the Renaissance. It was adapted by John Dryden in his very successful heroic drama Oedipus, licensed in 1678. The 1718 Oedipus was also the first play written by Voltaire. A version of Oedipus by Patrick McGuinness was performed at the National Theatre in late 2008, starring Ralph Fiennes and Claire Higgins.

In 1960, Immanuel Velikovsky (1895-1979) published a book called Oedipus and Akhnaton which made a comparison between the stories of the legendary Greek figure, Oedipus, and the historic Egyptian King of Thebes, Akhnaton. The book is presented as a thesis that combines with Velikovsky's series Ages in Chaos, concluding through his revision of Egyptian history that the Greeks who wrote the tragedy of Oedipus may have penned it in likeness of the life and story of Akhnaton, because in the revision Akhnaton would have lived much closer to the time when the legend first surfaced in Greece, providing an historical basis for the story. Each of the major characters in the Greek story are identified with the people involved in Akhnaton's family and court, and some interesting parallels are drawn.

Oedipus or Oedipais?

It has been suggested by some that in the earliest Ur-myth of the hero, he was called Oedipais: "child of the swollen sea."[15] He was so named because of the method by which his birth parents tried to abandon him—by placing him in a chest and tossing it into the ocean. The mythic topos of forsaking a child to the sea or a river is well attested, found (e.g.) in the myths of Perseus, Telephus, Dionysus, Moses, and Romulus and Remus.[16] Over the centuries, however, Oedipais seems to have been corrupted into the familiar Oedipus: "swollen foot." And it was this new name that might have inspired the addition of a bizarre element to the story of Oedipus' abandonment on Mt. Cithaeron. Exposure on a mountain was in fact a common method of child abandonment in Ancient Greece. The binding of baby Oedipus' ankles, however, is unique; it can thus be argued that the ankle-binding was inelegantly grafted onto the Oedipus myth simply to explain his new name.

The Oedipus complex

Sigmund Freud used the name The Oedipus complex to explain the origin of certain neuroses in childhood. It is defined as a male child's unconscious desire for the exclusive love of his mother. This desire includes jealousy towards the father and the unconscious wish for that parent's death. Oedipus himself, as portrayed in the myth, did not suffer from this neurosis – at least, not towards Jocasta, whom he only met as an adult (if anything, such feelings would have been directed at Merope – but there is no hint of that). Freud reasoned that the ancient Greek audience, which heard the story told or saw the plays based on it, did know that Oedipus was actually killing his father and marrying his mother; the story being continually told and played therefore reflected a preoccupation with the theme.

The term oedipism is used in medicine for serious self inflicted eye injury, an extremely rare form of severe self-harm.

References in popular culture

- In Book II (ll. 100-3) of Chaucer's romance Troilus and Criseyde, Criseyde is reading a romance of Thebes, and tells Pandarus that "This romaunce is of Thebes that we rede (read); / And we han (have) herd (heard) how that kyng Layus deyde (died) / Thorugh (through) Edippus (Oedipus) his sone, and al that dede (deed);"

- The story of Oedipus is the subject of Igor Stravinsky's "opera-oratorio" Oedipus Rex.

- Jean Cocteau's play La Machine infernale is a retelling of the myth of Oedipus.

- The Noah and the Whale song "Jocasta" has lyrics which may reference to the myth of Oedipus; e.g. "When a baby's born let's turn it to the snow".

- The Doors song "The End" features a passage inspired by Oedipus Rex.

- Tom Lehrer song "Oedipus Rex" is a comedic representation of the myth.

- Regina Spektor song "Oedipus" contains various elements of the play, but mostly tells the story of the 32nd son of a king, who is neglected by his mother.

- Angel episode "Calvary Angelus" (Season 4, Episode 12): when taunting his son, Angelus says, "Doing your mom and trying to kill your dad. Hm. There should be a play."

- The Mel Brooks comedy film, History of the World Part I includes a vignette in which Comicus and Josephus encounter a blind beggar, shouting "Give to Oedipus." He somehow recognizes Josephus, greeting him with "Hey, Josephus!" Josephus replies, "Hey, motherfucker!"

- In the Woody Allen film New York Stories, the last of the 3 shorts is titled "Oedipus Wrecks".

- The first episode of Inspector Morse, based on Colin Dexter's novel The Dead of Jericho, has many references and themes from the play.

- In the 1997 Disney movie Hercules, Hercules is speaking to Meg and says "And that, that, play, that Oedipus thing, man I thought I had problems."

- Kafka on the Shore, a novel by Japanese author Haruki Murakami, follows the story of Kafka Tamura, haunted by his father's prophecy that many of Oedipus' misfortunes would also befall him.

- Darsh Darsh, a 2008 novel by Polish author Perry Ahn, mentions Oedipus in its prologue. "Oedipus knew" is frequently repeated by Bradford, the main character's cousin.

- The movie "Oedipus" features a character named "Oedipus" who is a potato.

- The third episode of the 1993-1994 Azerbaijani television show Monkey Please, Sophocles! tells the story of Oedipus as a satire of Surat Huseynov and the post-Soviet political climate.

- Iokaste: The Novel of the Mother-Wife of Oedipus, a novel by American authors Victoria Grossack and Alice Underwood, tells the Oedipus story from the point of view of his mother-wife, Jocasta.

- Blood Feuds, A novel of War World, by Jerry Pournelle and S.M. Stirling uses the same plot set in a futuristic world of savagery.

- In the popular comedy series Two and a Half Men, Charlie (played by Charlie Sheen) is informed that he has an Oedipus complex by neighbour Rose.

- The play Greek by Steven Berkoff re-creates the Oedipus myth in a 20th-century London East End setting. It was later turned into an opera by Mark-Anthony Turnage.

- In the FlashForward episode "The Garden of Forking Paths", Dyson Frost sends a message to Mark Benford written on the back of a picture of Oedipus. Benford speculates that the use of a picture of Oedipus might be a hidden message indicating that the actions they are taking in trying to avoid the fate that they have foreseen might actually be the very things that are bringing it about.

- In 2010, Luis Alfaro's play, "Oedipus El Rey," a Chicano retelling of Oedipus Rex, had its world premiere at the Magic Theatre in San Francisco.

See also

- Antigone

- Epigoni

- Oedipus the King

- Oedipus at Colonus

- Oedipus Complex

- Genetic attraction

Notes

- ↑ Euripides, Phoenissae

- ↑ Sophocles, Oedipus the King 1220-1226; Euripides, Phoenissae

- ↑ Sophocles, Oedipus the King 1026-1030; Euripides, Phoenissae

- ↑ Sophocles, Oedipus the King 132-137

- ↑ Pindar, Second Olympian Ode; Sophocles, Oedipus the King 473-488; Euripides, Phoenissae

- ↑ Sophocles, Oedipus the King 136, 1578; Euripides, Phoenissae

- ↑ Sophocles, Oedipus the King 1316

- ↑ Pindar, Second Olympian Ode

- ↑ R. Kannicht, Tragicorum Graecorum Fragmenta (TrGF) vol. 5.1, Göttingen 2004; see also F. Jouan - H. Van Looy, "Euripide. tome 8.2 - Fragments", Paris 2000

- ↑ Reviewed by Hugh Lloyd-Jones in "Gnomon" 35 (1963), pp. 446-447

- ↑ Joachim Dingel, in "Museum Helveticum" 27 (1970), 90-96

- ↑ Apollodorus, House of Oedipus III.5.7

- ↑ See (e.g.) Brown 1976, 206-19.

- ↑ E.F. Watling's Introduction to Seneca: Four Tragedies and Octavia

- ↑ See (e.g.) Lowry 1995, 879; Carloni/Nobili 2004, 147 n.1.

- ↑ This version of the Oedipus myth is in fact attested in some scholia (at lines 13 and 26) to Euripides' Phoenician Women.

References

- Brown, A.L. "The End of the Seven against Thebes" The Classical Quarterly 26.2 (1976) 206-19.

- Carloni, Glauco and Nobili, Daniela. La Mamma Cattiva: fenomenologia, antropologia e clinica del figlicidio (Rimini, 2004).

- Dallas, Ian, Oedipus and Dionysus, Freiburg Press, Granada 1991. ISBN 1-874216-02-9.

- Graves, Robert, The Greek Myths

- Lowry, Malcolm. Sursum Corda!: The Collected Letters of Malcolm Lowry (Toronto, 1995).

- Ola Rotimi, "The gods are not to blame" three crown books Nigeria 1974

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Laius |

Mythical King of Thebes | Succeeded by Creon |