Nuremberg

| Nürnberg Nuremberg |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Coordinates | |

| Administration | |

| Country | Germany |

|---|---|

| State | Bavaria |

| Admin. region | Middle Franconia |

| District | Urban district |

| Mayor | Ulrich Maly (SPD) |

| Basic statistics | |

| Area | 186.38 km2 (71.96 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 302 m (991 ft) |

| Population | 503,673 (31 December 2009)[1] |

| - Density | 2,702 /km2 (6,999 /sq mi) |

| - Urban | 2,506,021 |

| Other information | |

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) |

| Licence plate | N |

| Postal codes | 90000-90491 |

| Area code | 0911 |

| Website | nuernberg.de |

Nuremberg (German: Nürnberg [ˈnʏɐ̯nbɛɐ̯k], not to be confused with Nürburg) is a city in the German state of Bavaria, in the administrative region of Middle Franconia. It is situated on the Pegnitz river and the Rhine–Main–Danube Canal and is Franconia's largest city. It is located about 170 kilometres north of Munich, at 49.27° N 11.5° E. The population (as of January 2006) is 500,132. The urban area of Nuremberg has 1,2 million inhabitants.

Contents |

History

Middle Ages

(from the Nuremberg Chronicle).

Nuremberg was probably founded around the turn of the 11th century, according to the first documentary mention of the city in 1050, as the location of an Imperial castle between the East Franks and the Bavarian March of the Nordgau.[2] From 1050 to 1571, the city expanded and rose dramatically in importance due to its location on key trade routes. King Conrad III established a burgraviate, with the first burgraves coming from the Austrian House of Raab but, with the extinction of their male line around 1190, the burgraviate was inherited by the last count's son-in-law, of the House of Hohenzollern. From the late 12th century to the Interregnum (1254–73), however, the power of the burgraves diminished as the Staufen emperors transferred most non-military powers to a castellan, with the city administration and the municipal courts handed over to an Imperial mayor (German: Reichsschultheiß) from 1173/74.[2][3] The strained relations between the burgraves and the castellan, with gradual transferral of powers to the latter in the late-14th and early-15th centuries, finally broke out into open enmity, which greatly influenced the history of the city.[3]

Nuremberg is often referred to as having been the 'unofficial capital' of the Holy Roman Empire, particularly because Reichstage (Imperial Diets) and courts met at Nuremberg Castle. The Diets of Nuremberg were an important part of the administrative structure of the empire. The increasing demand of the royal court and the increasing importance of the city attracted increased trade and commerce to Nuremberg. In 1219, Frederick II granted the Großen Freiheitsbrief (English: Great Letter of Freedom), including town rights, Reichsfreiheit (or Imperial immediacy), the privilege to mint coins and an independent customs policy, almost wholly removing the city from the purview of the burgraves.[2][3] Nuremberg soon became, with Augsburg, one of the two great trade centers on the route from Italy to Northern Europe. In 1298, the Jews of the town were accused of having desecrated the host and 698 were slain in one of the many Rintfleisch Massacres. Behind the massacre in 1298 was also the desire to combine the northern and southern parts of the city, which were divided by the Pegnitz river.

The largest gains for Nuremberg were in the 14th century; including Charles IV's Golden Bull of 1356, naming Nuremberg as the city where newly-elected kings of Germany must hold their first Reichstag, making Nuremberg one of the three highest cities of the Empire.[2] Charles was the patron of the Nuremberg Frauenkirche, built between 1352 and 1362 (the architect was likely Peter Parler), where the Imperial court worshipped during its stays in Nuremberg. The royal and Imperial connection was strengthened when Sigismund of Luxembourg granted the Imperial regalia to be kept permanently in Nuremberg in 1423, where they remained until 1796, when the advancing French troops required their removal to Regensburg and thence to Vienna.[2]

In 1349 the members of the guilds unsuccessfully rebelled against the patricians in the Handwerkeraufstand (English: Craftsmen's Uprising), supported by merchants and some councillors, leading to a ban on any self-organisation of the artisans in the city, abolishing the guilds that were customary elsewhere in Europe; the unions were then dissolved, and the oligarchs remained in power while Nuremberg was a free city.[2][3] Charles IV conferred upon the city the right to conclude alliances independently, thereby placing it upon a politically equal footing with the princes of the empire.[3] Frequent fights took place with the burgraves without, however, inflicting lasting damage upon the city. After the castle had been destroyed by fire in 1420 during a feud between Frederick IV (since 1417 margrave of Brandenburg) and the duke of Bavaria-Ingolstadt, the ruins and the forest belonging to the castle were purchased by the city (1427), resulting in the city's total sovereignty within its borders. Through these and other acquisitions the city accumulated considerable territory.[3] The Hussite Wars, recurrence of the Black Death in 1437, and the First Margrave War led to a severe fall in population in the mid-15th century.[3] At the beginning of the 16th century, siding with Albert IV, Duke of Bavaria-Munich, in the Landshut War of Succession led the city to gain substantial territory, resulting in lands of 25 sq mi (65 km2), becoming one of the largest Imperial cities.[3]

Early modern age

The cultural flowering of Nuremberg, in the 15th and 16th centuries, made it the center of the German Renaissance. In 1525, Nuremberg accepted the Protestant Reformation, and in 1532, the religious Peace of Nuremberg, by which the Lutherans gained important concessions, was signed there.[3] During the 1552 revolution against Charles V, Nuremberg tried to purchase its neutrality, but the city was attacked without a declaration of war and was forced into a disadvantageous peace.[3] At the Peace of Augsburg, the possessions of the Protestants were confirmed by the Emperor, their religious privileges extended and their independence from the Bishop of Bamberg affirmed, while the 1520s' secularisation of the monasteries was also approved.[3]

The state of affairs in the early 16th century, increased trade routes elsewhere and the ossification of the social hierarchy and legal structures contributed to the decline in trade.[3] Frequent quartering of Imperial, Swedish and League soldiers, the financial costs of the war and the cessation of trade caused irreparable damage to the city and a near-halving of the population.[3] In 1632, the city, occupied by the forces of Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, was besieged by the army of Imperial general Albrecht von Wallenstein. The city declined after the war and recovered its importance only in the 19th century, when it grew as an industrial center. Even after the Thirty Years' War, however, there was a late flowering of architecture and culture — secular Baroque architecture is exemplified in the layout of the civic gardens built outside the city walls, and in the Protestant city's rebuilding of the Egidienkirche, destroyed by fire at the beginning of the 18th century, considered a significant contribution to the baroque church architecture of Middle Franconia.[2]

After the Thirty Years' War, Nuremberg attempted to remain detached from external affairs, but contributions were demanded for the War of the Austrian Succession and the Seven Years' War and restrictions of imports and exports deprived the city of many markets for its manufactures.[3] The Bavarian elector, Charles Theodore, appropriated part of the land obtained by the city during the Landshut War of Succession, to which Bavaria had maintained its claim; Prussia also claimed part of the territory. Realising its weakness, the city asked to be incorporated into Prussia but Frederick William II refused, fearing to offend Austria, Russia and France.[3] At the Imperial diet in 1803, the independence of Nuremberg was affirmed, but on the signing of the Confederation of the Rhine on 12 July 1806, the city was agreed to be handed over to Bavaria from 8 September, with Bavaria guaranteeing the amortisation of the city's 12.5 million guilder public debt.[3]

After the Great French War

After the fall of Napoleon, the city's trade and commerce revived; the skill of its inhabitants together with its favourable situation soon rendered the city prosperous, particularly after its public debt had been acknowledged as a part of the Bavarian national debt. Having been incorporated into a Catholic country, the city was compelled to refrain from further discrimination against Catholics, who had been excluded from the rights of citizenship. Catholic services had been celebrated in the city by the priests of the Teutonic Order, often under great difficulties. Their possessions having been confiscated by the Bavarian government in 1806, they were given the Frauenkirche on the Market in 1809; in 1810 the first Catholic parish was established, which in 1818 numbered 1010 souls.[3]

In 1817, the city was incorporated into the district of Rezatkreis (named for the Franconian Rezat river), which was renamed to Middle Franconia (German: Mittelfranken) on 1 January 1838.[3] The first German railway, the Bavarian Ludwigsbahn, from Nuremberg to nearby Fürth, was opened in 1835. The establishment of railways and the joining of Bavaria into Zollverein (the 19th century German Customs Union), commerce and industry opened the way to greater prosperity.[3] In 1852, there were 53,638 inhabitants: 46,441 Protestants and 6616 Catholics. Since then, it grew to become the most important industrial city of Bavaria and one of the most prosperous towns of southern Germany[3]. In 1905, its population, including several incorporated suburbs, was 291,351: 86,943 Catholics, 196,913 Protestants, 3738 Jews and 3766 members of other creeds.[3]

Nazi era

Nuremberg held great significance during the Nazi Germany era. Because of the city's relevance to the Holy Roman Empire and its position in the centre of Germany, the Nazi Party chose the city to be the site of huge Nazi Party conventions — the Nuremberg rallies. The rallies were held annually from 1927 to 1938 in Nuremberg. After Adolf Hitler's rise to power in 1933 the Nuremberg rallies became huge Nazi propaganda events, a center of Nazi ideals. The 1934 rally was filmed by Leni Riefenstahl, and made into a propaganda film called Triumph des Willens (Triumph of the Will). At the 1935 rally, Hitler specifically ordered the Reichstag to convene at Nuremberg to pass the anti-Semitic Nuremberg Laws which revoked German citizenship for all Jews. A number of premises were constructed solely for these assemblies, some of which were not finished. Today many examples of Nazi architecture can still be seen in the city. The city was also the home of the Nazi propagandist Julius Streicher, the publisher of Der Stürmer.

During World War II, Nuremberg was the headquarters of Wehrkreis (military district) XIII, and an important site for military production, including airplanes, submarines, and tank engines. A subcamp of Flossenbürg concentration camp was located here. Extensive use was made of slave labour.[4] The city was severely damaged in Allied strategic bombing from 1943–45. On January 2, 1945, the medieval city centre was systematically bombed by the Royal Air Force and the U.S. Army Air Forces and about ninety percent of it was destroyed in only one hour, with 1,800 residents killed and roughly 100,000 displaced. In February 1945, additional attacks followed. In total, about 6,000 Nuremberg residents are estimated to have been killed in air raids. Despite this, the city was rebuilt after the war and was to some extent, restored to its pre-war appearance including the reconstruction of some of its medieval buildings.[5]

Nuremberg Trials

Between 1945 and 1946, German officials involved in the Holocaust and other war crimes were brought before an international tribunal in the Nuremberg Trials. The Soviet Union had wanted these trials to take place in Berlin, but Nuremberg was chosen as the site for the trials for specific reasons:

- The city had been the location of the Nazi Party's Nuremberg rallies and the laws stripping Jews of their citizenship were passed there. There was symbolic value in making it the place of Nazi demise.

- The Palace of Justice was spacious and largely undamaged (one of the few that had remained largely intact despite extensive Allied bombing of Germany). The already large courtroom was reasonably easily expanded by the removal of the wall at the end opposite the bench, thereby incorporating the adjoining room. A large prison was also part of the complex.

- As a compromise, it was agreed that Berlin would become the permanent seat of the International Military Tribunal and that the first trial (several were planned) would take place in Nuremberg. Due to the Cold War, subsequent trials never took place.

The same courtroom in Nuremberg was the venue of the Nuremberg Military Tribunals, organised by the United States as occupying power in the area.

Geography

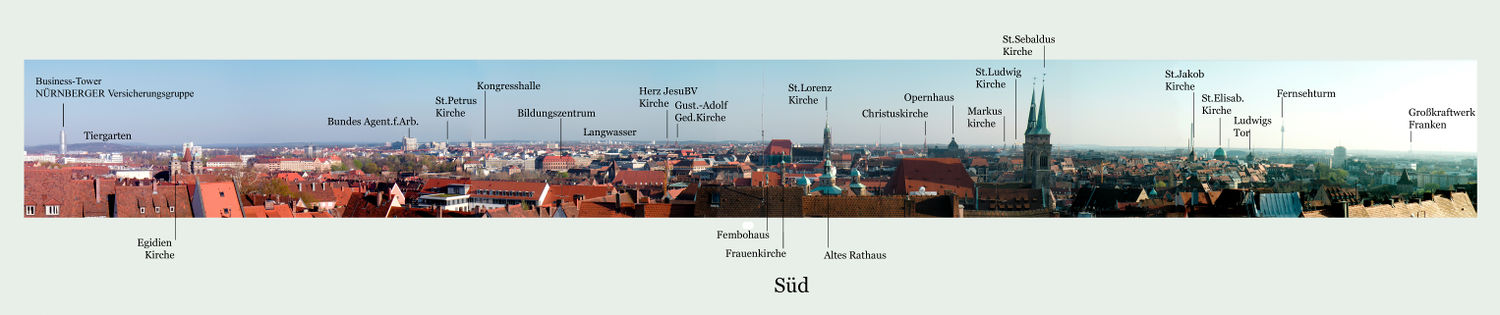

Several old villages now belong to the city, for example Grossgründlach, Kraftshof, Thon, and Neunhof in the north-west; Ziegelstein in the north-east, Altenfurt and Fischbach in the south-east; and Katzwang, Kornburg in the south. Langwasser is a modern suburb.

Economy

Nuremberg for many people is still associated with its traditional gingerbread (Lebkuchen) products, sausages, and handmade toys. Pocket watches — Nuremberg eggs — were made here in the sixteenth century by Peter Henlein. In the nineteenth century Nuremberg became the "industrial heart" of Bavaria with companies such as Siemens and MAN establishing a strong base in the city. Nuremberg is still an important industrial center with a strong standing in the markets of Central and Eastern Europe. Items manufactured in the area include electrical equipment, mechanical and optical products, motor vehicles, writing and drawing paraphernalia, stationery products, and printed materials. The city is also strong in the fields of automation, energy, and medical technology. Siemens is still the largest industrial employer in the Nuremberg region but a good third of German market research agencies is also located in the city. The Nuremberg International Toy Fair is the largest of its kind in the world. The city also hosts several specialist hi-tech fairs every year, attracting experts from every corner of the globe.

Culture

Nuremberg was an early center of humanism, science, printing, and mechanical invention.

The city contributed much to the science of astronomy. In 1471 Johannes Mueller of Königsberg (Bavaria), later called Regiomontanus, built an astronomical observatory in Nuremberg and published many important astronomical charts. In 1515, Albrecht Dürer, a native of Nuremberg, mapped the stars of the northern and southern hemispheres, producing the first printed star charts, which had been ordered by Johannes Stabius. Around 1515 Dürer also published the "Stabiussche Weltkarte", the first perspective drawing of the terrestrial globe. Perhaps most famously, the main part of Nicolaus Copernicus's work was published in Nuremberg in 1543.

Printers and publishers have a long history in Nuremberg. Many of these publishers worked with well-known artists of the day to produce books that could also be considered works of art. In 1470 Anton Koberger opened Europe's first print shop in Nuremberg. In 1493, he published the Nuremberg Chronicles, also known as the World Chronicles (Schedelsche Weltchronik), an illustrated history of the world from the creation to the present day. It was written in the local Franconian dialect by Hartmann Schedel and had illustrations by Michael Wohlgemuth, Wilhelm Pleydenwurff, and Albrecht Dürer. Others furthered geographical knowledge and travel by map making. Notable among these was navigator and geographer Martin Behaim, who made the first world globe.

Sculptors such as Veit Stoss, Adam Kraft and Peter Vischer are also associated with Nuremberg.

Composed of prosperous artisans, the guilds of the Meistersingers flourished here. Richard Wagner made their most famous member, Hans Sachs, the hero of his opera Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. Baroque composer Johann Pachelbel was born here and was organist of St. Sebaldus Church.

Nuremberg also has an academy of fine arts, which is the oldest art academy in central Europe.

Nuremberg is also famous for its Christkindlesmarkt (Christmas market), which draws well over a million shoppers each year. The market is famous for its handmade ornaments and delicacies.

Main sights

The southern part of the old town, known as Lorenzer Seite, is separated from the north by the river Pegnitz and encircled to the south by the city walls.

- Nuremberg Castle: the three castles that tower over the city including central burgraves' castle, with Free Reich's buildings to the east, the Imperial castle to the west.

- Heilig-Geist-Spital. In the centre of the city, on the bank of the river Pegnitz, stands the Hospital of the Holy Spirit. Founded in 1332, this is one of the largest hospitals of the Middle Ages. Lepers were kept here at some distance from the other patients. It now houses elderly persons and a restaurant.

- Hauptmarkt, which provides a picturesque setting and famous market for gingerbread. Nuremberg's star attraction is the Gothic Schöner Brunnen (Beautiful Fountain) which was erected around 1385 but subsequently replaced with a replica (the original fountain is kept in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum). The unchanged Renaissance bridge Fleischbrücke crosses the Pegnitz nearby.

- The following churches are located inside the city walls: St. Sebaldus Church, St. Lorenz, Frauenkirche (Our Lady's Church), Saint Klara, Saint Martha, Saint Jakob, Saint Egidien, and Saint Elisabeth.

- Gothic St Lorenz-Kirche (St. Lorenz church, St. Lorenz), one of the most important buildings in Nuremberg. The main body was built around 1270-1350.

- The church of the former Katharinenkloster is preserved as a ruin, the charterhouse (Kartause) is integrated into the building of the Germanisches Nationalmuseum and the choir of the former Franziskanerkirche is part of a modern building.

- The Walburga Chapel and the Romanesque Doppelkapelle (Chapel with two floors) are part of Nuremberg Castle.

- The Johannisfriedhof is a medieval cemetery, containing many old graves (Albrecht Dürer, Willibald Pirckheimer, and others). The Rochusfriedhof or the Wöhrder Kirchhof are near the Old Town.

- The Tiergarten Nürnberg is a zoo stretching over more than 60 ha in the Nürnberger Reichswald. It is the home of Flocke, an orphan polar bear cub who in 2008 became a major attraction and a figure of a large publicity campaign for Nuremberg's metropolitan region.

- There is also a medieval market just inside the city walls, selling handcrafted goods.

- The German National Railways Museum (German) (an Anchor Point of ERIH, The European Route of Industrial Heritage) is located in Nuremberg.

- The Nuremberg Ring (now welded within an iron fence) is said to bring good luck to those that touch it.

- The Nazi party rally grounds with the documentation-centre.

Transport

The city's location next to numerous highways, railways, and a waterway has contributed to its rising importance for trade with Eastern Europe.

Motorways

Nuremberg is conveniently located at the junction of several important Autobahn routes. The A3 (Netherlands–Frankfurt–Würzburg–Vienna) passes in a south-easterly direction along the north-east of the city. The A9 (Berlin–Munich) passes in a north–south direction on the east of the city. The A6 (France–Saarbrücken–Prague) passes in an east–west direction to the south of the city. Finally, the A73 begins in the south-east of Nuremberg and travels north-west through the city before continuing towards Fürth and Bamberg.

Railways

Nürnberg Hauptbahnhof is a stop for IC and ICE trains on the German long-distance railway network. The Nuremberg–Ingolstadt–Munich High-Speed line with 300 km/h operation opened May 28, 2006, and was fully integrated into the rail schedule on December 10, 2006. Travel times to Munich have been reduced to as little as one hour.

Airport

Nuremberg Airport has flights to major German cities and many European destinations, as well as connecting flights worldwide, for example via Frankfurt or Vienna. Air Berlin uses Nuremberg Airport as the airline's hub, especially in the winter season.

City and regional transport

The first segment of the Nuremberg U-Bahn metro system was opened in 1972. The system, along with trams and buses, are operated by the VAG Nürnberg (Verkehrsaktiengesellschaft Nürnberg or Nuremberg Transport Corporation), itself a member of the VGN (Verkehrsverbund Grossraum Nürnberg or Greater Nuremberg Transport Network). There is also a Nuremberg S-Bahn suburban metro railway and a regional train network, both centred on Nuremberg Central Station. Since 2008, Nuremberg has had the first U-Bahn in Germany (U3) that works without driver. It also is the first subway system worldwide in which both driver-operated trains and computer-controlled trains share tracks.

Canals

Nuremberg is an important port on the Main–Danube Canal.

Sport

Football

1. FC Nuremberg, known locally as Der Club, was founded in 1900 and plays in the Bundesliga. The official colours of the association are red and white, but the traditional colours are red and black. The current president is Franz Schäfer. They play in the EasyCredit Stadium, which was rebuilt for the World Cup in 2006 and accommodates 48,553 spectators.

- German Champion: 1920, 1921, 1924, 1925, 1927, 1936, 1948, 1961, 1968

- German Cup: 1935, 1939, 1962, 2007

International relations

Twin towns / Sister cities

Nuremberg is twinned with:

Nice, France, since 1954

Nice, France, since 1954 Kraków, Poland, since 1979[6]

Kraków, Poland, since 1979[6] Skopje, Macedonia, since 1982[7]

Skopje, Macedonia, since 1982[7] Glasgow, United Kingdom since 1985

Glasgow, United Kingdom since 1985 San Carlos, Nicaragua, since 1985

San Carlos, Nicaragua, since 1985 Gera, Germany, since 1988, renewed 1997

Gera, Germany, since 1988, renewed 1997 Prague, Czech Republic, since 1990

Prague, Czech Republic, since 1990 Kharkiv, Ukraine, since 1990

Kharkiv, Ukraine, since 1990 Hadera, Israel, since 1995

Hadera, Israel, since 1995 Shenzhen, China since 1997 (For this reason, Shenzhen set its European Contact Agency in Nuremberg)

Shenzhen, China since 1997 (For this reason, Shenzhen set its European Contact Agency in Nuremberg) Antalya, Turkey, since 1997

Antalya, Turkey, since 1997 Kavala, Greece, since 1998

Kavala, Greece, since 1998 Atlanta, United States, since 1998

Atlanta, United States, since 1998 Venice, Italy, since 1999

Venice, Italy, since 1999

Partner cities

Apart from the official twin towns (sister cities), there are a number with which Nuremberg maintains "cordial relations":[8]

Klausen / Chiusa, Italy 1970

Klausen / Chiusa, Italy 1970 Kalkudah, Sri Lanka 2005

Kalkudah, Sri Lanka 2005 Verona, Italy 2006

Verona, Italy 2006 Kronstadt/Brasov, Romania 2006

Kronstadt/Brasov, Romania 2006 Bologna, Italy 2006

Bologna, Italy 2006 Bar, Montenegro 2006

Bar, Montenegro 2006 Cordoba, Spain 2008

Cordoba, Spain 2008

There is also economic co-operation with other regions or towns, such as:

Changping, China 2006

Changping, China 2006

Famous citizens

- Chaya Arbel (Israeli composer)

- Hans Behaim the Elder

- Heinz Bernard (British Israeli actor-director)

- Ernst von Bibra

- Peter Bucher

- Sandra Bullock[9]

- Albrecht Dürer

- Ludwig Andreas Feuerbach

- Kaspar Hauser

- Peter Henlein

- Siegfried Jerusalem

- Hermann Kesten (writer)

- Anton Koberger

- Eliyahu Koren, graphic designer

- Adam Kraft (sculptor and architect)

- Kunz Lochner

- Max Morlock

- Johann Pachelbel

- Conrad Paumann

- Hans Sachs

- Hartmann Schedel

- Alexander Schreiner organist, Mormon Tabernacle

- Veit Stoss

- Peter Vischer the Elder

- Johann Christoph Volckamer who authored here his Hesperides.

- Johann Philipp von Wurzelbauer

See also

- Nürnberger Bratwürste (Nuremberg sausage)

- Academy of Fine Arts Nuremberg

- List of mayors of Nuremberg

- Norisring Racetrack, where Pedro Rodriguez died in 1971

- Nuremberg Toy Museum ("Spielzeugmuseum")

- Nuremberg U-Bahn Nuremberg Underground railway

- Tinsel (invented in Nuremberg)

- Triumph of the Will of Leni Riefenstahl

References

- ↑ "Fortschreibung des Bevölkerungsstandes" (in German). Bayerisches Landesamt für Statistik und Datenverarbeitung. 31 December 2009. https://www.statistikdaten.bayern.de/genesis/online/online?sequenz=statistiken&selectionname=12411.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 (German) Nürnberg, Reichsstadt: Politische und soziale Entwicklung (Political and Social Development of the Imperial City of Nuremberg), Historisches Lexikon Bayerns

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 "Nuremberg". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11168a.htm.

- ↑ Christine O'Keefe. Concentration Camps

- ↑ Neil Gregor, Haunted City. Nuremberg and the Nazi Past (New Haven, 2008

- ↑ "Kraków otwarty na świat". www.krakow.pl. http://www.krakow.pl/otwarty_na_swiat/?LANG=UK&MENU=l&TYPE=ART&ART_ID=16. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ↑ "Official portal of City of Skopje — Skopje Sister Cities". © 2006–09 City of Skopje. http://www.skopje.gov.mk/EN/DesktopDefault.aspx?tabindex=0&tabid=69. Retrieved 2009-07-14.

- ↑ "Befreundete Kommunen" (in German). Official Web site of the city of Nuremberg. Nuremberg Office for International Relations. http://www.nuernberg.de/internet/international/befreundete_kommunen.html. Retrieved 2009-04-18.

- ↑ "Die Nette von nebenan" (in German). Kino.de. http://www.kino.de/mitwirk.php4?typ=filmstarportrait&nr=24935&PHPSESSID=79bcb28af46330971138e0880b77c9b7. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

External links

- English website of the city

- Nuremberg travel guide from Wikitravel

- 49 digitised objects on Nuremberg in The European Library

|

Frankfurt, Würzburg | Erlangen, Bamberg, Erfurt | Bayreuth, Hof, Chemnitz |  |

| Mannheim, Fürth | Amberg, Pilsen, Praha | |||

| Stuttgart, Ulm, Aalen | Ingolstadt, Augsburg, Munich | Regensburg, Passau, Salzburg |

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||