Number

A number is a mathematical object used in counting and measuring. A notational symbol which represents a number is called a numeral, but in common usage the word number is used for both the abstract object and the symbol, as well as for the word for the number. In addition to their use in counting and measuring, numerals are often used for labels (telephone numbers), for ordering (serial numbers), and for codes (e.g., ISBNs). In mathematics, the definition of number has been extended over the years to include such numbers as zero, negative numbers, rational numbers, irrational numbers, and complex numbers.

Certain procedures which take one or more numbers as input and produce a number as output are called numerical operations. Unary operations take a single input number and produce a single output number. For example, the successor operation adds one to an integer, thus the successor of 4 is 5. More common are binary operations which take two input numbers and produce a single output number. Examples of binary operations include addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, and exponentiation. The study of numerical operations is called arithmetic.

Contents |

Classification of numbers

Different types of numbers are used in different cases. Numbers can be classified into sets, called number systems. (For different methods of expressing numbers with symbols, such as the Roman numerals, see numeral systems.)

| Natural | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, ..., n |

|---|---|

| Integers | −n, ..., −5, −4, −3, −2, −1, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, ..., n |

| Positive integers | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, ..., n |

| Rational | a/b where a and b are integers and b is not zero |

| Real | The limit of a convergent sequence of rational numbers |

| Complex | a + bi where a and b are real numbers and i is the square root of −1 |

Natural numbers

The most familiar numbers are the natural numbers or counting numbers: one, two, three, and so on. Traditionally, the sequence of natural numbers started with 1. However, in the 19th century, set theorists and other mathematicians started the convention of including 0 in the set of natural numbers. The mathematical symbol for the set of all natural numbers is N, also written  .

.

In the base ten number system, in almost universal use today by humans for arithmetic operations, the symbols for natural numbers are written using ten digits: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9. In this base ten system, the rightmost digit of a natural number has a place value of one, and every other digit has a place value ten times that of the place value of the digit to its right.

In set theory, which is capable of acting as an axiomatic foundation for modern mathematics[1], natural numbers can be represented by classes of equivalent sets. For instance, the number 3 can be represented as the class of all sets that have exactly three elements. Alternatively, in Peano Arithmetic, the number 3 is represented as sss0, where s is the "successor" function (i.e., 3 is the third successor of 0). Many different representations are possible; all that is needed to formally represent 3 is to inscribe a certain symbol or pattern of symbols three times.

Integers

Negative numbers are numbers that are less than zero. They are the opposite of positive numbers. For example, if a positive number indicates a bank deposit, then a negative number indicates a withdrawal of the same amount. Negative numbers are usually written with a negative sign (also called a minus sign) in front of the number they are the opposite of. Thus the opposite of 7 is written −7. When the set of negative numbers is combined with the natural numbers and zero, the result is the set of integer numbers, also called integers, Z also written  . Here the letter Z comes from German Zahl, meaning "number". The set of integers forms a ring with operations addition and multiplication.[2]

. Here the letter Z comes from German Zahl, meaning "number". The set of integers forms a ring with operations addition and multiplication.[2]

Rational numbers

A rational number is a number that can be expressed as a fraction with an integer numerator and a non-zero natural number denominator. Fractions are written as two numbers, the numerator and the denominator, with a dividing bar between them. In the fraction written m/n or

m represents equal parts, where n equal parts of that size make up one whole. Two different fractions may correspond to the same rational number; for example 1/2 and 2/4 are equal, that is:

If the absolute value of m is greater than n, then the absolute value of the fraction is greater than 1. Fractions can be greater than, less than, or equal to 1 and can also be positive, negative, or zero. The set of all rational numbers includes the integers, since every integer can be written as a fraction with denominator 1. For example −7 can be written −7/1. The symbol for the rational numbers is Q (for quotient), also written  .

.

Real numbers

The real numbers include all of the measuring numbers. Real numbers are usually written using decimal numerals, in which a decimal point is placed to the right of the digit with place value one. Each digit to the right of the decimal point has a place value one-tenth of the place value of the digit to its left. Thus

represents 1 hundred, 2 tens, 3 ones, 4 tenths, 5 hundredths, and 6 thousandths. In saying the number, the decimal is read "point", thus: "one two three point four five six ". In the US and UK and a number of other countries, the decimal point is represented by a period, whereas in continental Europe and certain other countries the decimal point is represented by a comma. Zero is often written as 0.0 when necessary to indicate that it is to be treated as a real number rather than as an integer; in the US and UK a number between −1 and 1 is always written with a leading zero so that the decimal point is more apparent, in other countries it may not be. Negative real numbers are written with a preceding minus sign:

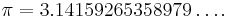

Every rational number is also a real number. It is not the case, however, that every real number is rational. If a real number cannot be written as a fraction of two integers, it is called irrational. A decimal that can be written as a fraction either ends (terminates) or forever repeats, because it is the answer to a problem in division. Thus the real number 0.5 can be written as 1/2 and the real number 0.333... (forever repeating threes, otherwise written 0.3) can be written as 1/3. On the other hand, the real number π (pi), the ratio of the circumference of any circle to its diameter, is

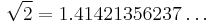

Since the decimal neither ends nor forever repeats, it cannot be written as a fraction, and is an example of an irrational number. Other irrational numbers include

(the square root of 2, that is, the positive number whose square is 2).

Thus 1.0 and 0.999... are two different decimal numerals representing the natural number 1. There are infinitely many other ways of representing the number 1, for example 2/2, 3/3, 1.00, 1.000, and so on.

Every real number is either rational or irrational. Every real number corresponds to a point on the number line. The real numbers also have an important but highly technical property called the least upper bound property. The symbol for the real numbers is R or  .

.

When a real number represents a measurement, there is always a margin of error. This is often indicated by rounding or truncating a decimal, so that digits that suggest a greater accuracy than the measurement itself are removed. The remaining digits are called significant digits. For example, measurements with a ruler can seldom be made without a margin of error of at least 0.01 meters. If the sides of a rectangle are measured as 1.23 meters and 4.56 meters, then multiplication gives an area for the rectangle of 5.6088 square meters. Since only the first two digits after the decimal place are significant, this is usually rounded to 5.61.

In abstract algebra, it can be shown that any complete ordered field is isomorphic to the real numbers. The real numbers are not, however, an algebraically closed field.

Complex numbers

Moving to a greater level of abstraction, the real numbers can be extended to the complex numbers. This set of numbers arose, historically, from trying to find closed formulas for the roots of cubic and quartic polynomials. This led to expressions involving the square roots of negative numbers, and eventually to the definition of a new number: the square root of negative one, denoted by i, a symbol assigned by Leonhard Euler, and called the imaginary unit. The complex numbers consist of all numbers of the form

where a and b are real numbers. In the expression a + bi, the real number a is called the real part and bi is called the imaginary part. If the real part of a complex number is zero, then the number is called an imaginary number or is referred to as purely imaginary; if the imaginary part is zero, then the number is a real number. Thus the real numbers are a subset of the complex numbers. If the real and imaginary parts of a complex number are both integers, then the number is called a Gaussian integer. The symbol for the complex numbers is C or  .

.

In abstract algebra, the complex numbers are an example of an algebraically closed field, meaning that every polynomial with complex coefficients can be factored into linear factors. Like the real number system, the complex number system is a field and is complete, but unlike the real numbers it is not ordered. That is, there is no meaning in saying that i is greater than 1, nor is there any meaning in saying that i is less than 1. In technical terms, the complex numbers lack the trichotomy property.

Complex numbers correspond to points on the complex plane, sometimes called the Argand plane.

Each of the number systems mentioned above is a proper subset of the next number system. Symbolically,  .

.

Computable numbers

Moving to problems of computation, the computable numbers are determined in the set of the real numbers. The computable numbers, also known as the recursive numbers or the computable reals, are the real numbers that can be computed to within any desired precision by a finite, terminating algorithm. Equivalent definitions can be given using μ-recursive functions, Turing machines or λ-calculus as the formal representation of algorithms. The computable numbers form a real closed field and can be used in the place of real numbers for many, but not all, mathematical purposes.

Other types

Hyperreal and hypercomplex numbers are used in non-standard analysis. The hyperreals, or nonstandard reals (usually denoted as *R), denote an ordered field which is a proper extension of the ordered field of real numbers R and which satisfies the transfer principle. This principle allows true first order statements about R to be reinterpreted as true first order statements about *R.

Superreal and surreal numbers extend the real numbers by adding infinitesimally small numbers and infinitely large numbers, but still form fields.

The p-adic numbers may have infinitely long expansions to the left of the decimal point in the same way that real numbers may have infinitely long expansions to the right. The number system which results depends on what base is used for the digits: any base is possible, but a system with the best mathematical properties is obtained when the base is a prime number.

For dealing with infinite collections, the natural numbers have been generalized to the ordinal numbers and to the cardinal numbers. The former gives the ordering of the collection, while the latter gives its size. For the finite set, the ordinal and cardinal numbers are equivalent, but they differ in the infinite case.

A relation number is defined as the class of relations consisting of all those relations that are similar to one member of the class.[3]

Sets of numbers that are not subsets of the complex numbers are sometimes called hypercomplex numbers. They include the quaternions H, invented by Sir William Rowan Hamilton, in which multiplication is not commutative, and the octonions, in which multiplication is not associative. Elements of function fields of non-zero characteristic behave in some ways like numbers and are often regarded as numbers by number theorists.

Specific uses

There are also other sets of numbers with specialized uses. Some are subsets of the complex numbers. For example, algebraic numbers are the roots of polynomials with rational coefficients. Complex numbers that are not algebraic are called transcendental numbers.

An even number is an integer that is "evenly divisible" by 2, i.e., divisible by 2 without remainder; an odd number is an integer that is not evenly divisible by 2. (The old-fashioned term "evenly divisible" is now almost always shortened to "divisible".) A formal definition of an odd number is that it is an integer of the form n = 2k + 1, where k is an integer. An even number has the form n = 2k where k is an integer.

A perfect number is defined as a positive integer which is the sum of its proper positive divisors, that is, the sum of the positive divisors not including the number itself. Equivalently, a perfect number is a number that is half the sum of all of its positive divisors, or σ(n) = 2 n. The first perfect number is 6, because 1, 2, and 3 are its proper positive divisors and 1 + 2 + 3 = 6. The next perfect number is 28 = 1 + 2 + 4 + 7 + 14. The next perfect numbers are 496 and 8128 (sequence A000396 in OEIS). These first four perfect numbers were the only ones known to early Greek mathematics.

A figurate number is a number that can be represented as a regular and discrete geometric pattern (e.g. dots). If the pattern is polytopic, the figurate is labeled a polytopic number, and may be a polygonal number or a polyhedral number. Polytopic numbers for r = 2, 3, and 4 are:

- P2(n) = 1/2 n(n + 1) (triangular numbers)

- P3(n) = 1/6 n(n + 1)(n + 2) (tetrahedral numbers)

- P4(n) = 1/24 n(n + 1)(n + 2)(n + 3) (pentatopic numbers)

Numerals

Numbers should be distinguished from numerals, the symbols used to represent numbers. Boyer showed that Egyptians created the first ciphered numeral system. Greeks followed by mapping their counting numbers onto Ionian and Doric alpabets. The number five can be represented by both the base ten numeral '5', by the Roman numeral 'Ⅴ' and ciphered letters. Notations used to represent numbers are discussed in the article numeral systems. An important development in the history of numerals was the development of a positional system, like modern decimals, which can represent very large numbers. The Roman numerals require extra symbols for larger numbers.

History

The first use of numbers

It is speculated that the first known use of numbers dates back to around 35,000 BC. Bones and other artifacts have been discovered with marks cut into them which many consider to be tally marks. The uses of these tally marks may have been for counting elapsed time, such as numbers of days, or keeping records of quantities, such as of animals.

Tallying systems have no concept of place value (such as in the currently used decimal notation), which limit its representation of large numbers but are nonetheless considered the first kind of abstract numeral system.

The first known system with place value was the Mesopotamian base 60 system (ca. 3400 BC) and the earliest known base 10 system dates to 3100 BC in Egypt.[4]

Zero

The use of zero as a number should be distinguished from its use as a placeholder numeral in place-value systems. Many ancient texts used zero. Babylonian and Egyptian texts used it. Egyptians used the word nfr to denote zero balance in double entry accounting entries. Indian texts used a Sanskrit word Shunya to refer to the concept of void; in mathematics texts this word would often be used to refer to the number zero.[5]

Records show that the Ancient Greeks seemed unsure about the status of zero as a number: they asked themselves "how can 'nothing' be something?" leading to interesting philosophical and, by the Medieval period, religious arguments about the nature and existence of zero and the vacuum. The paradoxes of Zeno of Elea depend in large part on the uncertain interpretation of zero. (The ancient Greeks even questioned whether 1 was a number.)

The late Olmec people of south-central Mexico began to use a true zero (a shell glyph) in the New World possibly by the 4th century BC but certainly by 40 BC, which became an integral part of Maya numerals and the Maya calendar. Mayan arithmetic used base 4 and base 5 written as base 20. Sanchez in 1961 reported a base 4, base 5 'finger' abacus.

By 130 AD, Ptolemy, influenced by Hipparchus and the Babylonians, was using a symbol for zero (a small circle with a long overbar) within a sexagesimal numeral system otherwise using alphabetic Greek numerals. Because it was used alone, not as just a placeholder, this Hellenistic zero was the first documented use of a true zero in the Old World. In later Byzantine manuscripts of his Syntaxis Mathematica (Almagest), the Hellenistic zero had morphed into the Greek letter omicron (otherwise meaning 70).

Another true zero was used in tables alongside Roman numerals by 525 (first known use by Dionysius Exiguus), but as a word, nulla meaning nothing, not as a symbol. When division produced zero as a remainder, nihil, also meaning nothing, was used. These medieval zeros were used by all future medieval computists (calculators of Easter). An isolated use of their initial, N, was used in a table of Roman numerals by Bede or a colleague about 725, a true zero symbol.

An early documented use of the zero by Brahmagupta (in the Brahmasphutasiddhanta) dates to 628. He treated zero as a number and discussed operations involving it, including division. By this time (the 7th century) the concept had clearly reached Cambodia as Khmer numerals, and documentation shows the idea later spreading to China and the Islamic world.

Negative numbers

The abstract concept of negative numbers was recognised as early as 100 BC – 50 BC. The Chinese ”Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art” (Chinese: Jiu-zhang Suanshu) contains methods for finding the areas of figures; red rods were used to denote positive coefficients, black for negative.[6] This is the earliest known mention of negative numbers in the East; the first reference in a Western work was in the 3rd century in Greece. Diophantus referred to the equation equivalent to  (the solution would be negative) in Arithmetica, saying that the equation gave an absurd result.

(the solution would be negative) in Arithmetica, saying that the equation gave an absurd result.

During the 600s, negative numbers were in use in India to represent debts. Diophantus’ previous reference was discussed more explicitly by Indian mathematician Brahmagupta, in Brahma-Sphuta-Siddhanta 628, who used negative numbers to produce the general form quadratic formula that remains in use today. However, in the 12th century in India, Bhaskara gives negative roots for quadratic equations but says the negative value "is in this case not to be taken, for it is inadequate; people do not approve of negative roots."

European mathematicians, for the most part, resisted the concept of negative numbers until the 17th century, although Fibonacci allowed negative solutions in financial problems where they could be interpreted as debts (chapter 13 of Liber Abaci, 1202) and later as losses (in Flos). At the same time, the Chinese were indicating negative numbers either by drawing a diagonal stroke through the right-most nonzero digit of the corresponding positive number's numeral.[7] The first use of negative numbers in a European work was by Chuquet during the 15th century. He used them as exponents, but referred to them as “absurd numbers”.

As recently as the 18th century, it was common practice to ignore any negative results returned by equations on the assumption that they were meaningless, just as René Descartes did with negative solutions in a Cartesian coordinate system.

Rational numbers

It is likely that the concept of fractional numbers dates to prehistoric times. Even the Ancient Egyptians wrote math texts describing how to convert general fractions into their special notation. The RMP 2/n table and the Kahun Papyrus wrote out unit fraction series by using least common multiples. Classical Greek and Indian mathematicians made studies of the theory of rational numbers, as part of the general study of number theory. The best known of these is Euclid's Elements, dating to roughly 300 BC. Of the Indian texts, the most relevant is the Sthananga Sutra, which also covers number theory as part of a general study of mathematics.

The concept of decimal fractions is closely linked with decimal place-value notation; the two seem to have developed in tandem. For example, it is common for the Jain math sutras to include calculations of decimal-fraction approximations to pi or the square root of two. Similarly, Babylonian math texts had always used sexagesimal (base 60) fractions with great frequency.

Irrational numbers

The earliest known use of irrational numbers was in the Indian Sulba Sutras composed between 800-500 BC.[8] The first existence proofs of irrational numbers is usually attributed to Pythagoras, more specifically to the Pythagorean Hippasus of Metapontum, who produced a (most likely geometrical) proof of the irrationality of the square root of 2. The story goes that Hippasus discovered irrational numbers when trying to represent the square root of 2 as a fraction. However Pythagoras believed in the absoluteness of numbers, and could not accept the existence of irrational numbers. He could not disprove their existence through logic, but his beliefs would not accept the existence of irrational numbers and so he sentenced Hippasus to death by drowning.

The sixteenth century saw the final acceptance by Europeans of negative, integral and fractional numbers. The seventeenth century saw decimal fractions with the modern notation quite generally used by mathematicians. But it was not until the nineteenth century that the irrationals were separated into algebraic and transcendental parts, and a scientific study of theory of irrationals was taken once more. It had remained almost dormant since Euclid. The year 1872 saw the publication of the theories of Karl Weierstrass (by his pupil Kossak), Heine (Crelle, 74), Georg Cantor (Annalen, 5), and Richard Dedekind. Méray had taken in 1869 the same point of departure as Heine, but the theory is generally referred to the year 1872. Weierstrass's method has been completely set forth by Salvatore Pincherle (1880), and Dedekind's has received additional prominence through the author's later work (1888) and the recent endorsement by Paul Tannery (1894). Weierstrass, Cantor, and Heine base their theories on infinite series, while Dedekind founds his on the idea of a cut (Schnitt) in the system of real numbers, separating all rational numbers into two groups having certain characteristic properties. The subject has received later contributions at the hands of Weierstrass, Kronecker (Crelle, 101), and Méray.

Continued fractions, closely related to irrational numbers (and due to Cataldi, 1613), received attention at the hands of Euler, and at the opening of the nineteenth century were brought into prominence through the writings of Joseph Louis Lagrange. Other noteworthy contributions have been made by Druckenmüller (1837), Kunze (1857), Lemke (1870), and Günther (1872). Ramus (1855) first connected the subject with determinants, resulting, with the subsequent contributions of Heine, Möbius, and Günther, in the theory of Kettenbruchdeterminanten. Dirichlet also added to the general theory, as have numerous contributors to the applications of the subject.

Transcendental numbers and reals

The first results concerning transcendental numbers were Lambert's 1761 proof that π cannot be rational, and also that en is irrational if n is rational (unless n = 0). (The constant e was first referred to in Napier's 1618 work on logarithms.) Legendre extended this proof to show that π is not the square root of a rational number. The search for roots of quintic and higher degree equations was an important development, the Abel–Ruffini theorem (Ruffini 1799, Abel 1824) showed that they could not be solved by radicals (formula involving only arithmetical operations and roots). Hence it was necessary to consider the wider set of algebraic numbers (all solutions to polynomial equations). Galois (1832) linked polynomial equations to group theory giving rise to the field of Galois theory.

Even the set of algebraic numbers was not sufficient and the full set of real number includes transcendental numbers.[9] The existence of which was first established by Liouville (1844, 1851). Hermite proved in 1873 that e is transcendental and Lindemann proved in 1882 that π is transcendental. Finally Cantor shows that the set of all real numbers is uncountably infinite but the set of all algebraic numbers is countably infinite, so there is an uncountably infinite number of transcendental numbers.

Infinity and infinitesimals

The earliest known conception of mathematical infinity appears in the Yajur Veda, an ancient Indian script, which at one point states "if you remove a part from infinity or add a part to infinity, still what remains is infinity". Infinity was a popular topic of philosophical study among the Jain mathematicians circa 400 BC. They distinguished between five types of infinity: infinite in one and two directions, infinite in area, infinite everywhere, and infinite perpetually.

In the West, the traditional notion of mathematical infinity was defined by Aristotle, who distinguished between actual infinity and potential infinity; the general consensus being that only the latter had true value. Galileo's Two New Sciences discussed the idea of one-to-one correspondences between infinite sets. But the next major advance in the theory was made by Georg Cantor; in 1895 he published a book about his new set theory, introducing, among other things, transfinite numbers and formulating the continuum hypothesis. This was the first mathematical model that represented infinity by numbers and gave rules for operating with these infinite numbers.

In the 1960s, Abraham Robinson showed how infinitely large and infinitesimal numbers can be rigorously defined and used to develop the field of nonstandard analysis. The system of hyperreal numbers represents a rigorous method of treating the ideas about infinite and infinitesimal numbers that had been used casually by mathematicians, scientists, and engineers ever since the invention of infinitesimal calculus by Newton and Leibniz.

A modern geometrical version of infinity is given by projective geometry, which introduces "ideal points at infinity," one for each spatial direction. Each family of parallel lines in a given direction is postulated to converge to the corresponding ideal point. This is closely related to the idea of vanishing points in perspective drawing.

Complex numbers

The earliest fleeting reference to square roots of negative numbers occurred in the work of the mathematician and inventor Heron of Alexandria in the 1st century AD, when he considered the volume of an impossible frustum of a pyramid. They became more prominent when in the 16th century closed formulas for the roots of third and fourth degree polynomials were discovered by Italian mathematicians such as Niccolo Fontana Tartaglia and Gerolamo Cardano. It was soon realized that these formulas, even if one was only interested in real solutions, sometimes required the manipulation of square roots of negative numbers.

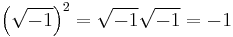

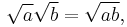

This was doubly unsettling since they did not even consider negative numbers to be on firm ground at the time. The term "imaginary" for these quantities was coined by René Descartes in 1637 and was meant to be derogatory (see imaginary number for a discussion of the "reality" of complex numbers). A further source of confusion was that the equation

seemed to be capriciously inconsistent with the algebraic identity

which is valid for positive real numbers a and b, and which was also used in complex number calculations with one of a, b positive and the other negative. The incorrect use of this identity, and the related identity

in the case when both a and b are negative even bedeviled Euler. This difficulty eventually led him to the convention of using the special symbol i in place of  to guard against this mistake.

to guard against this mistake.

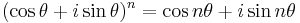

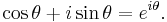

The 18th century saw the work of Abraham de Moivre and Leonhard Euler. de Moivre's formula (1730) states:

and to Euler (1748) Euler's formula of complex analysis:

The existence of complex numbers was not completely accepted until the geometrical interpretation had been described by Caspar Wessel in 1799; it was rediscovered several years later and popularized by Carl Friedrich Gauss, and as a result the theory of complex numbers received a notable expansion. The idea of the graphic representation of complex numbers had appeared, however, as early as 1685, in Wallis's De Algebra tractatus.

Also in 1799, Gauss provided the first generally accepted proof of the fundamental theorem of algebra, showing that every polynomial over the complex numbers has a full set of solutions in that realm. The general acceptance of the theory of complex numbers is not a little due to the labors of Augustin Louis Cauchy and Niels Henrik Abel, and especially the latter, who was the first to boldly use complex numbers with a success that is well known.

Gauss studied complex numbers of the form a + bi, where a and b are integral, or rational (and i is one of the two roots of x2 + 1 = 0). His student, Ferdinand Eisenstein, studied the type a + bω, where ω is a complex root of x3 − 1 = 0. Other such classes (called cyclotomic fields) of complex numbers are derived from the roots of unity xk − 1 = 0 for higher values of k. This generalization is largely due to Ernst Kummer, who also invented ideal numbers, which were expressed as geometrical entities by Felix Klein in 1893. The general theory of fields was created by Évariste Galois, who studied the fields generated by the roots of any polynomial equation F(x) = 0.

In 1850 Victor Alexandre Puiseux took the key step of distinguishing between poles and branch points, and introduced the concept of essential singular points; this would eventually lead to the concept of the extended complex plane.

Prime numbers

Prime numbers have been studied throughout recorded history. Euclid devoted one book of the Elements to the theory of primes; in it he proved the infinitude of the primes and the fundamental theorem of arithmetic, and presented the Euclidean algorithm for finding the greatest common divisor of two numbers.

In 240 BC, Eratosthenes used the Sieve of Eratosthenes to quickly isolate prime numbers. But most further development of the theory of primes in Europe dates to the Renaissance and later eras.

In 1796, Adrien-Marie Legendre conjectured the prime number theorem, describing the asymptotic distribution of primes. Other results concerning the distribution of the primes include Euler's proof that the sum of the reciprocals of the primes diverges, and the Goldbach conjecture which claims that any sufficiently large even number is the sum of two primes. Yet another conjecture related to the distribution of prime numbers is the Riemann hypothesis, formulated by Bernhard Riemann in 1859. The prime number theorem was finally proved by Jacques Hadamard and Charles de la Vallée-Poussin in 1896. The conjectures of Goldbach and Riemann yet remain to be proved or refuted.

Word alternatives

Some numbers traditionally have alternative words to express them, including the following:

- Pair, couple, brace: 2

- Dozen: 12

- Baker's dozen: 13

- Score: 20

- Gross: 144

- Ream: 480 (old measure) 500 (new measure)

- Great gross: 1728

See also

- Indian numerals

- Hebrew numerals

- Arabic numerals

- Roman numerals

- Floating point representation in computers

- List of numbers

- List of numbers in various languages

- Mathematical constants

- Mythical numbers

- Orders of magnitude

- Physical constants

- Subitizing and counting

- Number sign

- Numero sign

- The Foundations of Arithmetic

References

- ↑ Suppes, Patrick (1972). Axiomatic Set Theory. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 1. ISBN 0486616304.

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W.. "Integer". MathWorld -- A Wolfram Web Resource.. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Integer.html. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- ↑ Russell, Bertrand (1919). Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy. Routledge. pp. 56. ISBN 0415096049.

- ↑ http://www.math.buffalo.edu/mad/Ancient-Africa/mad_ancient_egyptpapyrus.html#berlin

- ↑ http://sunsite.utk.edu/math_archives/.http/hypermail/historia/apr99/0197.html

- ↑ Staszkow, Ronald; Robert Bradshaw (2004). The Mathematical Palette (3rd ed.). Brooks Cole. pp. 41. ISBN 0534403654.

- ↑ Smith, David Eugene (1958). History of Modern Mathematics. Dover Publications. pp. 259. ISBN 0486204294.

- ↑ Selin, Helaine (2000). Mathematics across cultures: the history of non-Western mathematics. Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 451. ISBN 0792364813.

- ↑ Bogomolny, A.. "What's a number?". Interactive Mathematics Miscellany and Puzzles. http://www.cut-the-knot.org/do_you_know/numbers.shtml. Retrieved 11 July 2010.

- Tobias Dantzig, Number, the language of science; a critical survey written for the cultured non-mathematician, New York, The Macmillan company, 1930.

- Erich Friedman, What's special about this number?

- Steven Galovich, Introduction to Mathematical Structures, Harcourt Brace Javanovich, 23 January 1989, ISBN 0-15-543468-3.

- Paul Halmos, Naive Set Theory, Springer, 1974, ISBN 0-387-90092-6.

- Morris Kline, Mathematical Thought from Ancient to Modern Times, Oxford University Press, 1972.

- Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell, Principia Mathematica to *56, Cambridge University Press, 1910.

- George I. Sanchez, Arithmetic in Maya,Austin-Texas, 1961.

External links

- http://eom.springer.de/A/a013260.htm

- Mesopotamian and Germanic numbers

- BBC Radio 4, In Our Time: Negative Numbers

- '4000 Years of Numbers', lecture by Robin Wilson, 07/11/07, Gresham College (available for download as MP3 or MP4, and as a text file).

- http://planetmath.org/encyclopedia/MayanMath2.html

|

|||||||||||

) ·

) ·  )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

)