Virus

- EE82EE"

- EE82EE"

colspan=2 style="text-align: center; background-color:

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Rotavirus | |

colspan=2 style="text-align: center; background-color:

|

|

| Group: | I–VII |

colspan=2 style="text-align: center; background-color:

|

|

|

I: dsDNA viruses |

|

A virus is a small infectious agent that can replicate only inside the living cells of organisms. Most viruses are too small to be seen directly with a light microscope. Viruses infect all types of organisms, from animals and plants to bacteria and archaea.[1] Since the initial discovery of tobacco mosaic virus by Martinus Beijerinck in 1898,[2] about 5,000 viruses have been described in detail,[3] although there are millions of different types.[4] Viruses are found in almost every ecosystem on Earth and are the most abundant type of biological entity.[5][6] The study of viruses is known as virology, a sub-speciality of microbiology.

Virus particles (known as virions) consist of two or three parts: the genetic material made from either DNA or RNA, long molecules that carry genetic information; a protein coat that protects these genes; and in some cases an envelope of lipids that surrounds the protein coat when they are outside a cell. The shapes of viruses range from simple helical and icosahedral forms to more complex structures. The average virus is about one one-hundredth the size of the average bacterium.

The origins of viruses in the evolutionary history of life are unclear: some may have evolved from plasmids — pieces of DNA that can move between cells — while others may have evolved from bacteria. In evolution, viruses are an important means of horizontal gene transfer, which increases genetic diversity.[7]

Viruses spread in many ways; plant viruses are often transmitted from plant to plant by insects that feed on sap, such as aphids, while animal viruses can be carried by blood-sucking insects. These disease-bearing organisms are known as vectors. Influenza viruses are spread by coughing and sneezing. The norovirus and rotavirus, common causes of viral gastroenteritis, are transmitted by the faecal-oral route and are passed from person to person by contact, entering the body in food or water. HIV is one of several viruses transmitted through sexual contact and by exposure to infected blood. Viruses can infect only a limited range of host cells called the "host range". This can be narrow or, as when a virus is capable of infecting many species, broad.[8]

Viral infections in animals provoke an immune response that usually eliminates the infecting virus. Immune responses can also be produced by vaccines, which confer an artificially acquired immunity to the specific viral infection. However, some viruses including those causing AIDS and viral hepatitis evade these immune responses and result in chronic infections. Antibiotics have no effect on viruses, but several antiviral drugs have been developed.

Contents |

Etymology

The word is from the Latin virus referring to poison and other noxious substances, first used in English in 1392.[9] Virulent, from Latin virulentus (poisonous), dates to 1400.[10] A meaning of "agent that causes infectious disease" is first recorded in 1728,[9] before the discovery of viruses by Dmitry Ivanovsky in 1892. The plural is viruses. The adjective viral dates to 1948.[11] The term virion is also used to refer to a single infective viral particle.

History

Louis Pasteur was unable to find a causative agent for rabies and had speculated about a pathogen too small to be detected by optical microscope.[12] In 1884, the French microbiologist Charles Chamberland invented a filter (known today as the Chamberland filter or Chamberland-Pasteur filter) with pores smaller than bacteria. Thus, he could pass a solution containing bacteria through the filter and completely remove them from the solution.[13] In 1892, the Russian biologist Dmitry Ivanovsky used this filter to study what is now known as the tobacco mosaic virus. His experiments showed that crushed leaf extracts from infected tobacco plants remain infectious after filtration. Ivanovsky suggested the infection might be caused by a toxin produced by bacteria, but did not pursue the idea.[14] At the time it was thought that all infectious agents could be retained by filters and grown on a nutrient medium—this was part of the germ theory of disease.[2] In 1898, the Dutch microbiologist Martinus Beijerinck repeated the experiments and became convinced that the filtered solution contained a new form of infectious agent.[15] He observed that the agent multiplied only in cells that were dividing, but as his experiments did not show that it was made of particles, he called it a contagium vivum fluidum (soluble living germ) and re-introduced the word virus.[14] Beijerinck maintained that viruses were liquid in nature, a theory later discredited by Wendell Stanley, who proved they were particulate.[14] In the same year, 1899, Friedrich Loeffler and Frosch passed the agent of foot-and-mouth disease (aphthovirus) through a similar filter and ruled out the possibility of a toxin because of the reduced concentration; they concluded that the agent could replicate.[14]

In the early 20th century, the English bacteriologist Frederick Twort discovered a group of viruses that infect bacteria, now called bacteriophages[16] (or commonly phages), and the French-Canadian microbiologist Félix d'Herelle described viruses that, when added to bacteria on agar, would produce areas of dead bacteria. He accurately diluted a suspension of these viruses and discovered that the highest dilutions (lowest virus concentrations), rather than killing all the bacteria, formed discrete areas of dead organisms. Counting these areas and multiplying by the dilution factor allowed him to calculate the number of viruses in the original suspension.[17] Phages were heralded as a potential treatment for diseases such as typhoid and cholera, but their promise was forgotten with the development of penicillin. The study of phages provided insights into the switching on and off of genes, and a useful mechanism for introducing foreign genes into bacteria.

By the end of the 19th century, viruses were defined in terms of their infectivity, their ability to be filtered, and their requirement for living hosts. Viruses had been grown only in plants and animals. In 1906, Ross Granville Harrison invented a method for growing tissue in lymph, and, in 1913, E. Steinhardt, C. Israeli, and R. A. Lambert used this method to grow vaccinia virus in fragments of guinea pig corneal tissue.[18] In 1928, H. B. Maitland and M. C. Maitland grew vaccinia virus in suspensions of minced hens' kidneys. Their method was not widely adopted until the 1950s, when poliovirus was grown on a large scale for vaccine production.[19]

Another breakthrough came in 1931, when the American pathologist Ernest William Goodpasture grew influenza and several other viruses in fertilised chickens' eggs.[20] In 1949, John F. Enders, Thomas Weller, and Frederick Robbins grew polio virus in cultured human embryo cells, the first virus to be grown without using solid animal tissue or eggs. This work enabled Jonas Salk to make an effective polio vaccine.[21]

The first images of viruses were obtained upon the invention of electron microscopy in 1931 by the German engineers Ernst Ruska and Max Knoll.[22] In 1935, American biochemist and virologist Wendell Meredith Stanley examined the tobacco mosaic virus and found it was mostly made of protein.[23] A short time later, this virus was separated into protein and RNA parts.[24] The tobacco mosaic virus was the first to be crystallised and its structure could therefore be elucidated in detail. The first X-ray diffraction pictures of the crystallised virus were obtained by Bernal and Fankuchen in 1941. On the basis of her pictures, Rosalind Franklin discovered the full DNA structure of the virus in 1955.[25] In the same year, Heinz Fraenkel-Conrat and Robley Williams showed that purified tobacco mosaic virus RNA and its coat protein can assemble by themselves to form functional viruses, suggesting that this simple mechanism was probably the means through which viruses were created within their host cells.[26]

The second half of the 20th century was the golden age of virus discovery and most of the 2,000 recognised species of animal, plant, and bacterial viruses were discovered during these years.[27][28] In 1957, equine arterivirus and the cause of Bovine virus diarrhea (a pestivirus) were discovered. In 1963, the hepatitis B virus was discovered by Baruch Blumberg,[29] and in 1965, Howard Temin described the first retrovirus. Reverse transcriptase, the key enzyme that retroviruses use to translate their RNA into DNA, was first described in 1970, independently by Howard Martin Temin and David Baltimore.[30] In 1983 Luc Montagnier's team at the Pasteur Institute in France, first isolated the retrovirus now called HIV.[31]

Origins

Viruses are found wherever there is life and have probably existed since living cells first evolved.[32] The origin of viruses is unclear because they do not form fossils, so molecular techniques have been the most useful means of investigating how they arose.[33] These techniques rely on the availability of ancient viral DNA or RNA, but, unfortunately, most of the viruses that have been preserved and stored in laboratories are less than 90 years old.[34][35] There are three main hypotheses that try to explain the origins of viruses:[36][37]

- Regressive hypothesis

- Viruses may have once been small cells that parasitised larger cells. Over time, genes not required by their parasitism were lost. The bacteria rickettsia and chlamydia are living cells that, like viruses, can reproduce only inside host cells. They lend support to this hypothesis, as their dependence on parasitism is likely to have caused the loss of genes that enabled them to survive outside a cell. This is also called the degeneracy hypothesis.[38][39]

- Cellular origin hypothesis

- Some viruses may have evolved from bits of DNA or RNA that "escaped" from the genes of a larger organism. The escaped DNA could have come from plasmids (pieces of naked DNA that can move between cells) or transposons (molecules of DNA that replicate and move around to different positions within the genes of the cell).[40] Once called "jumping genes", transposons are examples of mobile genetic elements and could be the origin of some viruses. They were discovered in maize by Barbara McClintock in 1950.[41] This is sometimes called the vagrancy hypothesis.[38][42]

- Coevolution hypothesis

- Viruses may have evolved from complex molecules of protein and nucleic acid at the same time as cells first appeared on earth and would have been dependent on cellular life for billions of years. Viroids are molecules of RNA that are not classified as viruses because they lack a protein coat. However, they have characteristics that are common to several viruses and are often called subviral agents.[43] Viroids are important pathogens of plants.[44] They do not code for proteins but interact with the host cell and use the host machinery for their replication.[45] The hepatitis delta virus of humans has an RNA genome similar to viroids but has protein coat derived from hepatitis B virus and cannot produce one of its own. It is therefore a defective virus and cannot replicate without the help of hepatitis B virus.[46] Similarly, the virophage 'sputnik' is dependent on mimivirus, which infects the protozoan Acanthamoeba castellanii.[47] These viruses that are dependent on the presence of other virus species in the host cell are called satellites and may represent evolutionary intermediates of viroids and viruses.[48][49]

Prions are infectious protein molecules that do not contain DNA or RNA.[50] They cause an infection in sheep called scrapie and cattle bovine spongiform encephalopathy ("mad cow" disease). In humans they cause kuru and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.[51] They are able to replicate because some proteins can exist in two different shapes and the prion changes the normal shape of a host protein into the prion shape. This starts a chain reaction where each prion protein converts many host proteins into more prions, and these new prions then go on to convert even more protein into prions. Although they are fundamentally different from viruses and viroids, their discovery gives credence to the idea that viruses could have evolved from self-replicating molecules.[52]

Computer analysis of viral and host DNA sequences is giving a better understanding of the evolutionary relationships between different viruses and may help identify the ancestors of modern viruses. To date, such analyses have not helped to decide on which of these hypotheses are correct. However, it seems unlikely that all currently known viruses have a common ancestor and viruses have probably arisen numerous times in the past by one or more mechanisms.[53]

Microbiology

Life properties

Opinions differ on whether viruses are a form of life, or organic structures that interact with living organisms. They have been described as "organisms at the edge of life",[54] since they resemble organisms in that they possess genes and evolve by natural selection,[55] and reproduce by creating multiple copies of themselves through self-assembly. Although they have genes, they do not have a cellular structure, which is often seen as the basic unit of life. Viruses do not have their own metabolism, and require a host cell to make new products. They therefore cannot naturally reproduce outside a host cell[56] —although bacterial species such as rickettsia and chlamydia are considered living organisms despite the same limitation.[57][58] Accepted forms of life use cell division to reproduce, whereas viruses spontaneously assemble within cells. They differ from autonomous growth of crystals as they inherit genetic mutations while being subject to natural selection. Virus self-assembly within host cells has implications for the study of the origin of life, as it lends further credence to the hypothesis that life could have started as self-assembling organic molecules.[1]

Structure

Viruses display a wide diversity of shapes and sizes, called morphologies. Generally viruses are much smaller than bacteria. Most viruses that have been studied have a diameter between 10 and 300 nanometres. Some filoviruses have a total length of up to 1400 nm; their diameters are only about 80 nm.[59] Most viruses cannot be seen with a light microscope so scanning and transmission electron microscopes are used to visualise virions.[60] To increase the contrast between viruses and the background, electron-dense "stains" are used. These are solutions of salts of heavy metals, such as tungsten, that scatter the electrons from regions covered with the stain. When virions are coated with stain (positive staining), fine detail is obscured. Negative staining overcomes this problem by staining the background only.[61]

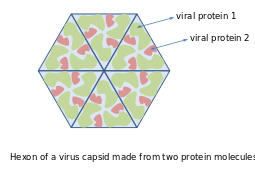

A complete virus particle, known as a virion, consists of nucleic acid surrounded by a protective coat of protein called a capsid. These are formed from identical protein subunits called capsomers.[62] Viruses can have a lipid "envelope" derived from the host cell membrane. The capsid is made from proteins encoded by the viral genome and its shape serves as the basis for morphological distinction.[63][64] Virally coded protein subunits will self-assemble to form a capsid, generally requiring the presence of the virus genome. Complex viruses code for proteins that assist in the construction of their capsid. Proteins associated with nucleic acid are known as nucleoproteins, and the association of viral capsid proteins with viral nucleic acid is called a nucleocapsid. The capsid and entire virus structure can be mechanically (physically) probed through atomic force microscopy.[65][66] In general, there are four main morphological virus types:

_Virus_PHIL_1878_lores.jpg)

- Helical

- These viruses are composed of a single type of capsomer stacked around a central axis to form a helical structure, which may have a central cavity, or hollow tube. This arrangement results in rod-shaped or filamentous virions: these can be short and highly rigid, or long and very flexible. The genetic material, generally single-stranded RNA, but ssDNA in some cases, is bound into the protein helix by interactions between the negatively charged nucleic acid and positive charges on the protein. Overall, the length of a helical capsid is related to the length of the nucleic acid contained within it and the diameter is dependent on the size and arrangement of capsomers. The well-studied Tobacco mosaic virus is an example of a helical virus.[67]

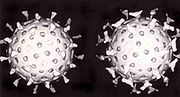

- Icosahedral

- Most animal viruses are icosahedral or near-spherical with icosahedral symmetry. A regular icosahedron is the optimum way of forming a closed shell from identical sub-units. The minimum number of identical capsomers required is twelve, each composed of five identical sub-units. Many viruses, such as rotavirus, have more than twelve capsomers and appear spherical but they retain this symmetry. Capsomers at the apices are surrounded by five other capsomers and are called pentons. Capsomers on the triangular faces are surround by six others and are call hexons.[68]

- Envelope

- Some species of virus envelop themselves in a modified form of one of the cell membranes, either the outer membrane surrounding an infected host cell, or internal membranes such as nuclear membrane or endoplasmic reticulum, thus gaining an outer lipid bilayer known as a viral envelope. This membrane is studded with proteins coded for by the viral genome and host genome; the lipid membrane itself and any carbohydrates present originate entirely from the host. The influenza virus and HIV use this strategy. Most enveloped viruses are dependent on the envelope for their infectivity.[69]

- Complex

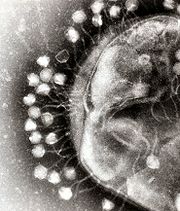

- These viruses possess a capsid that is neither purely helical, nor purely icosahedral, and that may possess extra structures such as protein tails or a complex outer wall. Some bacteriophages, such as Enterobacteria phage T4 have a complex structure consisting of an icosahedral head bound to a helical tail, which may have a hexagonal base plate with protruding protein tail fibres. This tail structure acts like a molecular syringe, attaching to the bacterial host and then injecting the viral genome into the cell.[70]

The poxviruses are large, complex viruses that have an unusual morphology. The viral genome is associated with proteins within a central disk structure known as a nucleoid. The nucleoid is surrounded by a membrane and two lateral bodies of unknown function. The virus has an outer envelope with a thick layer of protein studded over its surface. The whole virion is slightly pleiomorphic, ranging from ovoid to brick shape.[71] Mimivirus is the largest known virus, with a capsid diameter of 400 nm. Protein filaments measuring 100 nm project from the surface. The capsid appears hexagonal under an electron microscope, therefore the capsid is probably icosahedral.[72]

Some viruses that infect Archaea have complex structures that are unrelated to any other form of virus, with a wide variety of unusual shapes, ranging from spindle-shaped structures, to viruses that resemble hooked rods, teardrops or even bottles. Other archaeal viruses resemble the tailed bacteriophages, and can have multiple tail structures.[73]

Genome

| Property | Parameters |

|---|---|

| Nucleic acid |

|

| Shape |

|

| Strandedness |

|

| Sense |

|

An enormous variety of genomic structures can be seen among viral species; as a group they contain more structural genomic diversity than plants, animals, archaea, or bacteria. There are millions of different types of viruses;[4], though only about 5,000 of them have been described in detail.[3] A virus has either DNA or RNA genes and is called a DNA virus or a RNA virus respectively. The vast majority of viruses have RNA genomes. Plant viruses tend to have single-stranded RNA genomes and bacteriophages tend to have double-stranded DNA genomes.[74]

Viral genomes are circular, as in the polyomaviruses, or linear, as in the adenoviruses. The type of nucleic acid is irrelevant to the shape of the genome. Among RNA viruses, the genome is often divided up into separate parts within the virion, in which case it is called segmented. Each segment often codes for one protein and they are usually found together in one capsid. Every segment is not required to be in the same virion for the overall virus to be infectious, as demonstrated by the brome mosaic virus.[59]

A viral genome, irrespective of nucleic acid type, is either single-stranded or double-stranded. Single-stranded genomes consist of an unpaired nucleic acid, analogous to one-half of a ladder split down the middle. Double-stranded genomes consist of two complementary paired nucleic acids, analogous to a ladder. Some viruses, such as those belonging to the Hepadnaviridae, contain a genome that is partially double-stranded and partially single-stranded.[74]

For viruses with RNA or single-stranded DNA, the strands are said to be either positive-sense (called the plus-strand) or negative-sense (called the minus-strand), depending on whether it is complementary to the viral messenger RNA (mRNA). Positive-sense viral RNA is identical to viral mRNA and thus can be immediately translated by the host cell. Negative-sense viral RNA is complementary to mRNA and thus must be converted to positive-sense RNA by an RNA polymerase before translation. DNA nomenclature is similar to RNA nomenclature, in that the coding strand for the viral mRNA is complementary to it (−), and the non-coding strand is a copy of it (+).[74]

Genome size varies greatly between species. The smallest viral genomes code for only four proteins and have a mass of about 106 Daltons; the largest have a mass of about 108 Daltons and code for over one hundred proteins.[74] RNA viruses generally have smaller genome sizes than DNA viruses because of a higher error-rate when replicating, and have a maximum upper size limit. Beyond this limit, errors in the genome when replicating render the virus useless or uncompetitive. To compensate for this, RNA viruses often have segmented genomes where the genome is split into smaller molecules, thus reducing the chance of error. In contrast, DNA viruses generally have larger genomes because of the high fidelity of their replication enzymes.[75]

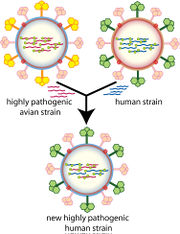

Viruses undergo genetic change by several mechanisms. These include a process called genetic drift where individual bases in the DNA or RNA mutate to other bases. Most of these point mutations are "silent"—they do not change the protein that the gene encodes—but others can confer evolutionary advantages such as resistance to antiviral drugs.[76] Antigenic shift occurs when there is a major change in the genome of the virus. This can be a result of recombination or reassortment. When this happens with influenza viruses, pandemics might result.[77] RNA viruses often exist as quasispecies or swarms of viruses of the same species but with slightly different genome nucleoside sequences. Such quasispecies are a prime target for natural selection.[78]

Segmented genomes confer evolutionary advantages; different strains of a virus with a segmented genome can shuffle and combine genes and produce progeny viruses or (offspring) that have unique characteristics. This is called reassortment or viral sex.[79]

Genetic recombination is the process by which a strand of DNA is broken and then joined to the end of a different DNA molecule. This can occur when viruses infect cells simultaneously and studies of viral evolution have shown that recombination has been rampant in the species studied.[80] Recombination is common to both RNA and DNA viruses.[81][82]

Replication cycle

Viral populations do not grow through cell division, because they are acellular. Instead, they use the machinery and metabolism of a host cell to produce multiple copies of themselves, and they assemble in the cell.

The life cycle of viruses differs greatly between species but there are six basic stages in the life cycle of viruses:[83]

- Attachment is a specific binding between viral capsid proteins and specific receptors on the host cellular surface. This specificity determines the host range of a virus. For example, HIV infects only human T cells, because its surface protein, gp120, can interact with CD4 and chemokine receptors on the T cell's surface. This mechanism has evolved to favour those viruses that only infect cells in which they are capable of replication. Attachment to the receptor can induce the viral-envelope protein to undergo changes that results in the fusion of viral and cellular membranes.

- Penetration follows attachment; viruses enter the host cell through receptor mediated endocytosis or membrane fusion. This is often called viral entry. The infection of plant cells is different from that of animal cells. Plants have a rigid cell wall made of cellulose, so most viruses can only get inside the cells after trauma to the cell wall.[84] However, viruses such as tobacco mosaic virus can also move directly in plants, from cell to cell, through pores called plasmodesmata.[85] Bacteria, like plants, have strong cell walls that a virus must breach to infect the cell. Some viruses have evolved mechanisms that inject their genome into the bacterial cell while the viral capsid remains outside.[86]

- Uncoating is a process in which the viral capsid is degraded by viral enzymes or host enzymes thus releasing the viral genomic nucleic acid.

- Replication involves synthesis of viral messenger RNA (mRNA) for viruses except positive sense RNA viruses, viral protein synthesis and assembly of viral proteins and viral genome replication.

- Following the assembly of the virus particles, post-translational modification of the viral proteins often occurs. In viruses such as HIV, this modification (sometimes called maturation) occurs after the virus has been released from the host cell.[87]

- Viruses are released from the host cell by lysis—a process that kills the cell by bursting its membrane. Some viruses undergo a lysogenic cycle where the viral genome is incorporated by genetic recombination into a specific place in the host's chromosome. The viral genome is then known as a "provirus" or, in the case of bacteriophages a "prophage".[88] Whenever the host divides, the viral genome is also replicated. The viral genome is mostly silent within the host; however, at some point, the provirus or prophage may give rise to active viruses, which lyse their host cells.[89] Enveloped viruses (e.g., HIV) typically are released from the host cell by budding. During this process the virus acquires its envelope, which is a modified piece of the host's plasma membrane.[90]

The genetic material within viruses, and the method by which the material is replicated, vary between different types of viruses.

- DNA viruses

- The genome replication of most DNA viruses takes place in the cell's nucleus. If the cell has the appropriate receptor on its surface, these viruses enter the cell by fusion with the cell membrane or by endocytosis. Most DNA viruses are entirely dependent on the host cell's DNA and RNA synthesising machinery, and RNA processing machinery. The viral genome must cross the cell's nuclear membrane to access this machinery.[91]

- RNA viruses

- Replication usually takes place in the cytoplasm. RNA viruses can be placed into about four different groups depending on their modes of replication. The polarity (whether or not it can be used directly to make proteins) of the RNA largely determines the replicative mechanism, and whether the genetic material is single-stranded or double-stranded. RNA viruses use their own RNA replicase enzymes to create copies of their genomes.[92]

- Reverse transcribing viruses

- These replicate using reverse transcription, which is the formation of DNA from an RNA template. Reverse transcribing viruses containing RNA genomes use a DNA intermediate to replicate, whereas those containing DNA genomes use an RNA intermediate during genome replication. Both types use the reverse transcriptase enzyme to carry out the nucleic acid conversion. Retroviruses often integrate the DNA produced by reverse transcription into the host genome. They are susceptible to antiviral drugs that inhibit the reverse transcriptase enzyme, e.g. zidovudine and lamivudine. An example of the first type is HIV, which is a retrovirus. Examples of the second type are the Hepadnaviridae, which includes Hepatitis B virus.[93]

Effects on the host cell

The range of structural and biochemical effects that viruses have on the host cell is extensive.[94] These are called cytopathic effects.[95] Most virus infections eventually result in the death of the host cell. The causes of death include cell lysis, alterations to the cell's surface membrane and apoptosis.[96] Often cell death is caused by cessation of its normal activities because of suppression by virus-specific proteins, not all of which are components of the virus particle.[97]

Some viruses cause no apparent changes to the infected cell. Cells in which the virus is latent and inactive show few signs of infection and often function normally.[98] This causes persistent infections and the virus is often dormant for many months or years. This is often the case with herpes viruses.[99][100] Some viruses, such as Epstein-Barr virus, can cause cells to proliferate without causing malignancy,[101] while others, such as papillomaviruses, are established causes of cancer.[102]

Host range

Viruses are by far the most abundant parasites on earth and they have been found to infect all types of cellular life including animals, plants and bacteria.[3] However, different types of viruses can only infect a limited range of hosts and many are species-specific. Some, such as smallpox virus for example, can only infect one species—in this case humans,[103] and are said to have a narrow host range. Other viruses, such as rabies virus, can infect different species of mammals and are said to have a broad range.[104] The viruses that infect plants are harmless to animals and most viruses that infect other animals are harmless to humans.[105] The host range of some bacteriophages is limited to a single strain of bacteria and they can be used to trace the source of outbreaks of infections by a method called phage typing.[106]

Classification

Classification seeks to describe the diversity of viruses by naming and grouping them on the basis of similarities. In 1962, André Lwoff, Robert Horne, and Paul Tournier were the first to develop a means of virus classification, based on the Linnaean hierarchical system.[107] This system bases classification on phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species. Viruses were grouped according to their shared properties (not those of their hosts) and the type of nucleic acid forming their genomes.[108] Later the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses was formed. However, viruses are not classified on the basis of phylum or class, as their small genome size and high rate of mutation makes it difficult to determine their ancestry beyond Order. As such the Baltimore Classification is used to supplement the more traditional hierarchy.

ICTV classification

The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) developed the current classification system and wrote guidelines that put a greater weight on certain virus properties to maintain family uniformity. A unified taxonomy (a universal system for classifying viruses) has been established. The 7th lCTV Report formalised for the first time the concept of the virus species as the lowest taxon (group) in a branching hierarchy of viral taxa.[109] However, at present only a small part of the total diversity of viruses has been studied, with analyses of samples from humans finding that about 20% of the virus sequences recovered have not been seen before, and samples from the environment, such as from seawater and ocean sediments, finding that the large majority of sequences are completely novel.[110]

The general taxonomic structure is as follows:

In the current (2008) ICTV taxonomy, five orders have been established, the Caudovirales, Herpesvirales, Mononegavirales, Nidovirales, and Picornavirales. The committee does not formally distinguish between subspecies, strains, and isolates. In total there are 5 orders, 82 families, 11 subfamilies, 307 genera, 2,083 species and about 3,000 types yet unclassified.[111][112]

Baltimore classification

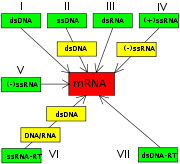

The Nobel Prize-winning biologist David Baltimore devised the Baltimore classification system.[30][113] The ICTV classification system is used in conjunction with the Baltimore classification system in modern virus classification.[114][115][116]

The Baltimore classification of viruses is based on the mechanism of mRNA production. Viruses must generate mRNAs from their genomes to produce proteins and replicate themselves, but different mechanisms are used to achieve this in each virus family. Viral genomes may be single-stranded (ss) or double-stranded (ds), RNA or DNA, and may or may not use reverse transcriptase (RT). Additionally, ssRNA viruses may be either sense (+) or antisense (−). This classification places viruses into seven groups:

- I: dsDNA viruses (e.g. Adenoviruses, Herpesviruses, Poxviruses)

- II: ssDNA viruses (+)sense DNA (e.g. Parvoviruses)

- III: dsRNA viruses (e.g. Reoviruses)

- IV: (+)ssRNA viruses (+)sense RNA (e.g. Picornaviruses, Togaviruses)

- V: (−)ssRNA viruses (−)sense RNA (e.g. Orthomyxoviruses, Rhabdoviruses)

- VI: ssRNA-RT viruses (+)sense RNA with DNA intermediate in life-cycle (e.g. Retroviruses)

- VII: dsDNA-RT viruses (e.g. Hepadnaviruses)

As an example of viral classification, the chicken pox virus, varicella zoster (VZV), belongs to the order Herpesvirales, family Herpesviridae, subfamily Alphaherpesvirinae, and genus Varicellovirus. VZV is in Group I of the Baltimore Classification because it is a dsDNA virus that does not use reverse transcriptase.

Viruses and human disease

Examples of common human diseases caused by viruses include the common cold, influenza, chickenpox and cold sores. Many serious diseases such as ebola, AIDS, avian influenza and SARS are caused by viruses. The relative ability of viruses to cause disease is described in terms of virulence. Other diseases are under investigation as to whether they too have a virus as the causative agent, such as the possible connection between human herpes virus six (HHV6) and neurological diseases such as multiple sclerosis and chronic fatigue syndrome.[119] There is controversy over whether the borna virus, previously thought to cause neurological diseases in horses, could be responsible for psychiatric illnesses in humans.[120]

Viruses have different mechanisms by which they produce disease in an organism, which largely depends on the viral species. Mechanisms at the cellular level primarily include cell lysis, the breaking open and subsequent death of the cell. In multicellular organisms, if enough cells die the whole organism will start to suffer the effects. Although viruses cause disruption of healthy homeostasis, resulting in disease, they may exist relatively harmlessly within an organism. An example would include the ability of the herpes simplex virus, which causes cold sores, to remain in a dormant state within the human body. This is called latency[121] and is a characteristic of the herpes viruses including Epstein-Barr virus, which causes glandular fever, and varicella zoster virus, which causes chickenpox. Most people have been infected with at least one of these types of herpes virus.[122] However, these latent viruses might sometimes be beneficial, as the presence of the virus can increase immunity against bacterial pathogens, such as Yersinia pestis.[123] On the other hand, latent chickenpox infections return in later life as the disease called shingles.

Some viruses can cause life-long or chronic infections, where the viruses continue to replicate in the body despite the host's defence mechanisms.[124] This is common in hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections. People chronically infected are known as carriers, as they serve as reservoirs of infectious virus.[125] In populations with a high proportion of carriers, the disease is said to be endemic.[126] In contrast to acute lytic viral infections this persistence implies compatible interactions with the host organism. Persistent viruses may even broaden the evolutionary potential of host species.[127]

Epidemiology

Viral epidemiology is the branch of medical science that deals with the transmission and control of virus infections in humans. Transmission of viruses can be vertical, that is from mother to child, or horizontal, which means from person to person. Examples of vertical transmission include hepatitis B virus and HIV where the baby is born already infected with the virus.[128] Another, more rare, example is the varicella zoster virus, which although causing relatively mild infections in humans, can be fatal to the foetus and newly born baby.[129] Horizontal transmission is the most common mechanism of spread of viruses in populations. Transmission can be exchange of blood by sexual activity, e.g. HIV, hepatitis B and hepatitis C; by mouth by exchange of saliva, e.g. Epstein-Barr virus, or from contaminated food or water, e.g. norovirus; by breathing in viruses in the form of aerosols, e.g. influenza virus; and by insect vectors such as mosquitoes, e.g. dengue. The rate or speed of transmission of viral infections depends on factors that include population density, the number of susceptible individuals, (i.e. those who are not immune),[130] the quality of health care and the weather.[131]

Epidemiology is used to break the chain of infection in populations during outbreaks of viral diseases.[132] Control measures are used that are based on knowledge of how the virus is transmitted. It is important to find the source, or sources, of the outbreak and to identify the virus. Once the virus has been identified, the chain of transmission can sometimes be broken by vaccines. When vaccines are not available sanitation and disinfection can be effective. Often infected people are isolated from the rest of the community and those that have been exposed to the virus placed in quarantine.[133] To control the outbreak of foot and mouth disease in cattle in Britain in 2001, thousands of cattle were slaughtered.[134] Most viral infections of humans and other animals have incubation periods during which the infection causes no signs or symptoms.[135] Incubation periods for viral diseases range from a few days to weeks but are known for most infections.[136] Somewhat overlapping, but mainly following the incubation period, there is a period of communicability; a time when an infected individual or animal is contagious and can infect another person or animal.[137] This too is known for many viral infections and knowledge the length of both periods is important in the control of outbreaks.[138] When outbreaks cause an unusually high proportion of cases in a population, community or region they are called epidemics. If outbreaks spread worldwide they are called pandemics.[139]

Epidemics and pandemics

Native American populations were devastated by contagious diseases, particularly smallpox, brought to the Americas by European colonists. It is unclear how many Native Americans were killed by foreign diseases after the arrival of Columbus in the Americas, but the numbers have been estimated to be close to 70% of the indigenous population. The damage done by this disease significantly aided European attempts to displace and conquer the native population.[140]

A pandemic is a worldwide epidemic. The 1918 flu pandemic, commonly referred to as the Spanish flu, was a category 5 influenza pandemic caused by an unusually severe and deadly influenza A virus. The victims were often healthy young adults, in contrast to most influenza outbreaks, which predominantly affect juvenile, elderly, or otherwise weakened patients.[141]

The Spanish flu pandemic lasted from 1918 to 1919. Older estimates say it killed 40–50 million people,[142] while more recent research suggests that it may have killed as many as 100 million people, or 5% of the world's population in 1918.[143] Most researchers believe that HIV originated in sub-Saharan Africa during the 20th century;[144] it is now a pandemic, with an estimated 38.6 million people now living with the disease worldwide.[145] The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and the World Health Organization (WHO) estimate that AIDS has killed more than 25 million people since it was first recognised on June 5, 1981, making it one of the most destructive epidemics in recorded history.[146] In 2007 there were 2.7 million new HIV infections and 2 million HIV-related deaths.[147]

Several highly lethal viral pathogens are members of the Filoviridae. Filoviruses are filament-like viruses that cause viral hemorrhagic fever, and include the ebola and marburg viruses. The Marburg virus attracted widespread press attention in April 2005 for an outbreak in Angola. Beginning in October 2004 and continuing into 2005, the outbreak was the world's worst epidemic of any kind of viral hemorrhagic fever.[148]

Cancer

Viruses are an established cause of cancer in humans and other species. Viral cancers only occur in a minority of infected persons (or animals). Cancer viruses come from a range of virus families, including both RNA and DNA viruses, and so there is no single type of "oncovirus" (an obsolete term originally used for acutely transforming retroviruses). The development of cancer is determined by a variety of factors such as host immunity[149] and mutations in the host.[150] Viruses accepted to cause human cancers include some genotypes of human papillomavirus, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, Epstein-Barr virus, Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus and human T-lymphotropic virus. The most recently discovered human cancer virus is a polyomavirus (Merkel cell polyomavirus) that causes most cases of a rare form of skin cancer called Merkel cell carcinoma.[151] Hepatitis viruses can develop into a chronic viral infection that leads to liver cancer.[152][153] Infection by human T-lymphotropic virus can lead to tropical spastic paraparesis and adult T-cell leukemia.[154] Human papillomaviruses are an established cause of cancers of cervix, skin, anus, and penis.[155] Within the Herpesviridae, Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus causes Kaposi's sarcoma and body cavity lymphoma, and Epstein–Barr virus causes Burkitt's lymphoma, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, B lymphoproliferative disorder and nasopharyngeal carcinoma.[156] Merkel cell polyomavirus closely related to SV40 and mouse polyomaviruses that have been used as animal models for cancer viruses for over 50 years.[157]

Host defence mechanisms

The body's first line of defence against viruses is the innate immune system. This comprises cells and other mechanisms that defend the host from infection in a non-specific manner. This means that the cells of the innate system recognise, and respond to, pathogens in a generic way, but unlike the adaptive immune system, it does not confer long-lasting or protective immunity to the host.[158]

RNA interference is an important innate defence against viruses.[159] Many viruses have a replication strategy that involves double-stranded RNA (dsRNA). When such a virus infects a cell, it releases its RNA molecule or molecules, which immediately bind to a protein complex called dicer that cuts the RNA into smaller pieces. A biochemical pathway called the RISC complex is activated, which degrades the viral mRNA and the cell survives the infection. Rotaviruses avoid this mechanism by not uncoating fully inside the cell and by releasing newly produced mRNA through pores in the particle's inner capsid. The genomic dsRNA remains protected inside the core of the virion.[160][161]

When the adaptive immune system of a vertebrate encounters a virus, it produces specific antibodies that bind to the virus and render it non-infectious. This is called humoral immunity. Two types of antibodies are important. The first called IgM is highly effective at neutralizing viruses but is only produced by the cells of the immune system for a few weeks. The second, called, IgG is produced indefinitely. The presence of IgM in the blood of the host is used to test for acute infection, whereas IgG indicates an infection sometime in the past.[162] IgG antibody is measured when tests for immunity are carried out.[163]

A second defence of vertebrates against viruses is called cell-mediated immunity and involves immune cells known as T cells. The body's cells constantly display short fragments of their proteins on the cell's surface, and if a T cell recognises a suspicious viral fragment there, the host cell is destroyed by killer T cells and the virus-specific T-cells proliferate. Cells such as the macrophage are specialists at this antigen presentation.[164] The production of interferon is an important host defence mechanism. This is a hormone produced by the body when viruses are present. Its role in immunity is complex, but it eventually stops the viruses from reproducing by killing the infected cell and its close neighbours.[165]

Not all virus infections produce a protective immune response in this way. HIV evades the immune system by constantly changing the amino acid sequence of the proteins on the surface of the virion. These persistent viruses evade immune control by sequestration, blockade of antigen presentation, cytokine resistance, evasion of natural killer cell activities, escape from apoptosis, and antigenic shift.[166] Other viruses, called neurotropic viruses, are disseminated by neural spread where the immune system may be unable to reach them.

Prevention and treatment

Because viruses use vital metabolic pathways within host cells to replicate, they are difficult to eliminate without using drugs that cause toxic effects to host cells in general. The most effective medical approaches to viral diseases are vaccinations to provide immunity to infection, and antiviral drugs that selectively interfere with viral replication.

Vaccines

Vaccination is a cheap and effective way of preventing infections by viruses. Vaccines were used to prevent viral infections long before the discovery of the actual viruses. Their use has resulted in a dramatic decline in morbidity (illness) and mortality (death) associated with viral infections such as polio, measles, mumps and rubella.[167] Smallpox infections have been eradicated.[168] Vaccines are available to prevent over thirteen viral infections of humans,[169] and more are used to prevent viral infections of animals.[170] Vaccines can consist of live-attenuated or killed viruses, or viral proteins (antigens).[171] Live vaccines contain weakened forms of the virus, which do not cause the disease but nonetheless confer immunity. Such viruses are called attenuated. Live vaccines can be dangerous when given to people with a weak immunity, (who are described as immunocompromised), because in these people, the weakened virus can cause the original disease.[172] Biotechnology and genetic engineering techniques are used to produce subunit vaccines. These vaccines use only the capsid proteins of the virus. Hepatitis B vaccine is an example of this type of vaccine.[173] Subunit vaccines are safe for immunocompromised patients because they cannot cause the disease.[174] The yellow fever virus vaccine, a live-attenuated strain called 17D, is probably the safest and most effective vaccine ever generated.[175]

Antiviral drugs

Antiviral drugs are often nucleoside analogues, (fake DNA building blocks), which viruses mistakenly incorporate into their genomes during replication. The life-cycle of the virus is then halted because the newly synthesised DNA is inactive. This is because these analogues lack the hydroxyl groups, which, along with phosphorus atoms, link together to form the strong "backbone" of the DNA molecule. This is called DNA chain termination.[176] Examples of nucleoside analogues are aciclovir for Herpes simplex virus infections and lamivudine for HIV and Hepatitis B virus infections. Aciclovir is one of the oldest and most frequently prescribed antiviral drugs.[177] Other antiviral drugs in use target different stages of the viral life cycle. HIV is dependent on a proteolytic enzyme called the HIV-1 protease for it to become fully infectious. There is a large class of drugs called protease inhibitors that inactivate this enzyme.

Hepatitis C is caused by an RNA virus. In 80% of people infected, the disease is chronic, and without treatment, they are infected for the remainder of their lives. However, there is now an effective treatment that uses the nucleoside analogue drug ribavirin combined with interferon.[178] The treatment of chronic carriers of the hepatitis B virus by using a similar strategy using lamivudine has been developed.[179]

Infection in other species

Viruses infect all cellular life and, although viruses occur universally, each cellular species has its own specific range that often infect only that species.[180] Some viruses, called satellites, can only replicate within cells that have already been infected by another virus.[181] Viruses are important pathogens of livestock. Diseases such as Foot and Mouth Disease and bluetongue are caused by viruses.[182] Companion animals such as cats, dogs, and horses, if not vaccinated, are susceptible to serious viral infections. Canine parvovirus is caused by a small DNA virus and infections are often fatal in pups.[183] Like all invertebrates, the honey bee is susceptible to many viral infections.[184] Fortunately, most viruses co-exist harmlessly in their host and cause no signs or symptoms of disease.[2]

Plants

There are many types of plant virus, but often they cause only a loss of yield, and it is not economically viable to try to control them. Plant viruses are often spread from plant to plant by organisms, known as vectors. These are normally insects, but some fungi, nematode worms and single-celled organisms have been shown to be vectors. When control of plant virus infections is considered economical, for perennial fruits for example, efforts are concentrated on killing the vectors and removing alternate hosts such as weeds.[185] Plant viruses are harmless to humans and other animals because they can reproduce only in living plant cells.[186]

Plants have elaborate and effective defence mechanisms against viruses. One of the most effective is the presence of so-called resistance (R) genes. Each R gene confers resistance to a particular virus by triggering localised areas of cell death around the infected cell, which can often be seen with the unaided eye as large spots. This stops the infection from spreading.[187] RNA interference is also an effective defence in plants.[188] When they are infected, plants often produce natural disinfectants that kill viruses, such as salicylic acid, nitric oxide, and reactive oxygen molecules.[189]

Plant virus particles or virus-like particles (VLPs) have applications in both biotechnology and nanotechnology. The capsids of most plant viruses are simple and robust structures and can be produced in large quantities either by the infection of plants or by expression in a variety of heterologous systems. Plant virus particles can be modified genetically and chemically to encapsulate foreign material and can be incorporated into supramolecular structures for use in biotechnology.[190]

Bacteria

Bacteriophages are a common and diverse group of viruses and are the most abundant form of biological entity in aquatic environments—there are up to ten times more of these viruses in the oceans than there are bacteria,[191] reaching levels of 250,000,000 bacteriophages per millilitre of seawater.[192] These viruses infect specific bacteria by binding to surface receptor molecules and then entering the cell. Within a short amount of time, in some cases just minutes, bacterial polymerase starts translating viral mRNA into protein. These proteins go on to become either new virions within the cell, helper proteins, which help assembly of new virions, or proteins involved in cell lysis. Viral enzymes aid in the breakdown of the cell membrane, and, in the case of the T4 phage, in just over twenty minutes after injection over three hundred phages could be released.[193]

The major way bacteria defend themselves from bacteriophages is by producing enzymes that destroy foreign DNA. These enzymes, called restriction endonucleases, cut up the viral DNA that bacteriophages inject into bacterial cells.[194] Bacteria also contain a system that uses CRISPR sequences to retain fragments of the genomes of viruses that the bacteria have come into contact with in the past, which allows them to block the virus's replication through a form of RNA interference.[195][196] This genetic system provides bacteria with acquired immunity to infection.

Archaea

Some viruses replicate within archaea: these are double-stranded DNA viruses with unusual and sometimes unique shapes.[5][73] These viruses have been studied in most detail in the thermophilic archaea, particularly the orders Sulfolobales and Thermoproteales.[197] Defences against these viruses may involve RNA interference from repetitive DNA sequences within archaean genomes that are related to the genes of the viruses.[198][199]

Role in aquatic ecosystems

Viruses are the most abundant biological entity in aquatic environments:[1] a teaspoon of seawater contains about one million of them.[200] They are essential to the regulation of saltwater and freshwater ecosystems.[201] Most of these viruses are bacteriophages, which are harmless to plants and animals. They infect and destroy the bacteria in aquatic microbial communities, comprising the most important mechanism of recycling carbon in the marine environment. The organic molecules released from the bacterial cells by the viruses stimulates fresh bacterial and algal growth.[202]

Microorganisms constitute more than 90% of the biomass in the sea. It is estimated that viruses kill approximately 20% of this biomass each day and that there are fifteen times as many viruses in the oceans as there are bacteria and archaea. Viruses are the main agents responsible for the rapid destruction of harmful algal blooms,[203] which often kill other marine life.[204] The number of viruses in the oceans decreases further offshore and deeper into the water, where there are fewer host organisms.[205]

The effects of marine viruses are far-reaching; by increasing the amount of respiration in the oceans, viruses are indirectly responsible for reducing the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere by approximately 3 gigatonnes of carbon per year.[205]

Like any organism, marine mammals are susceptible to viral infections. In 1988 and 2002 thousands of harbour seals that were killed in Europe in 1988 and 2002 by phocine distemper virus.[206] Many other viruses, including caliciviruses, herpesviruses, adenoviruses and parvoviruses, circulate in marine mammal populations.[205]

Role in evolution

Viruses are an important natural means of transferring genes between different species, which increases genetic diversity and drives evolution.[7] It is thought that viruses played a central role in the early evolution, before the diversification of bacteria, archaea and eukaryotes and at the time of the last universal common ancestor of life on Earth.[207] Viruses are still one of the largest reservoirs of unexplored genetic diversity on the Earth.[205]

Applications

Life sciences and medicine

Viruses are important to the study of molecular and cellular biology as they provide simple systems that can be used to manipulate and investigate the functions of cells.[208] The study and use of viruses have provided valuable information about aspects of cell biology.[209] For example, viruses have been useful in the study of genetics and helped our understanding of the basic mechanisms of molecular genetics, such as DNA replication, transcription, RNA processing, translation, protein transport, and immunology.

Geneticists often use viruses as vectors to introduce genes into cells that they are studying. This is useful for making the cell produce a foreign substance, or to study the effect of introducing a new gene into the genome. In similar fashion, virotherapy uses viruses as vectors to treat various diseases, as they can specifically target cells and DNA. It shows promising use in the treatment of cancer and in gene therapy. Eastern European scientists have used phage therapy as an alternative to antibiotics for some time, and interest in this approach is increasing, because of the high level of antibiotic resistance now found in some pathogenic bacteria.[210]

Expression of heterologous proteins by viruses is the basis of several manufacturing processes that are currently being used for the production of various proteins such as vaccine antigens and antibodies. Industrial processes have been recently developed using viral vectors and a number of pharmaceutical proteins are currently in pre-clinical and clinical trials.[211]

Materials science and nanotechnology

Current trends in nanotechnology promise to make much more versatile use of viruses. From the viewpoint of a materials scientist, viruses can be regarded as organic nanoparticles. Their surface carries specific tools designed to cross the barriers of their host cells. The size and shape of viruses, and the number and nature of the functional groups on their surface, is precisely defined. As such, viruses are commonly used in materials science as scaffolds for covalently linked surface modifications. A particular quality of viruses is that they can be tailored by directed evolution. The powerful techniques developed by life sciences are becoming the basis of engineering approaches towards nanomaterials, opening a wide range of applications far beyond biology and medicine.[212]

Because of their size, shape, and well-defined chemical structures, viruses have been used as templates for organizing materials on the nanoscale. Recent examples include work at the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, DC, using Cowpea Mosaic Virus (CPMV) particles to amplify signals in DNA microarray based sensors. In this application, the virus particles separate the fluorescent dyes used for signalling to prevent the formation of non-fluorescent dimers that act as quenchers.[213] Another example is the use of CPMV as a nanoscale breadboard for molecular electronics.[214]

Synthetic viruses

Many viruses can be synthesized de novo (“from scratch”) and the first synthetic virus was created in 2002.[215] Although somewhat of a misconception, it is not the actual virus that is synthesized, but rather its DNA genome (in case of a DNA virus), or a cDNA copy of its genome (in case of RNA viruses). For many virus families the naked synthetic DNA or RNA (once enzymatically converted back from the synthetic cDNA) is infectious when introduced into a cell. That is, they contain all the necessary information to produce new viruses. This technology is now being used to investigate novel vaccine strategies.[216] The ability to synthesize viruses has far-reaching consequences, since viruses can no longer be regarded as extinct, as long as the information of their genome sequence is known and permissive cells are available. Currently, the full-length genome sequences of 2408 different viruses (including smallpox) are publicly available at an online database, maintained by the National Institute of Health.[217]

Weapons

The ability of viruses to cause devastating epidemics in human societies has led to the concern that viruses could be weaponised for biological warfare. Further concern was raised by the successful recreation of the infamous 1918 influenza virus in a laboratory.[218] The smallpox virus devastated numerous societies throughout history before its eradication. There are officially only two centers in the world which keep stocks of smallpox virus—the Russian Vector laboratory, and the United States Centers for Disease Control.[219] But fears that it may be used as a weapon are not totally unfounded;[219] the vaccine for smallpox is not safe—during the years before the eradication of smallpox disease more people became seriously ill as a result of vaccination than did people from smallpox[220] — and smallpox vaccination is no longer universally practiced.[221] Thus, much of the modern human population has almost no established resistance to smallpox.[219]

References

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Koonin EV, Senkevich TG, Dolja VV. The ancient Virus World and evolution of cells. Biol. Direct. 2006 [cited 14 September 2008];1:29. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-1-29. PMID 16984643. PMC 1594570.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Dimmock p. 4

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Dimmock p. 49

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Breitbart M, Rohwer F. Here a virus, there a virus, everywhere the same virus?. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13(6):278–84. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2005.04.003. PMID 15936660.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Lawrence CM, Menon S, Eilers BJ, et al.. Structural and functional studies of archaeal viruses. J. Biol. Chem.. 2009;284(19):12599–603. doi:10.1074/jbc.R800078200. PMID 19158076. PMC 2675988.

- ↑ Edwards RA, Rohwer F. Viral metagenomics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.. 2005;3(6):504–10. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1163. PMID 15886693.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Canchaya C, Fournous G, Chibani-Chennoufi S, Dillmann ML, Brüssow H. Phage as agents of lateral gene transfer. Curr. Opin. Microbiol.. 2003;6(4):417–24. doi:10.1016/S1369-5274(03)00086-9. PMID 12941415.

- ↑ Shors pp. 49–50

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 virus [cited 12 September 2008].

- ↑ virulent, a. [cited 12 September 2008].

- ↑ viral, a. [cited 12 September 2008].

- ↑ Bordenave G (May 2003). "Louis Pasteur (1822-1895)". Microbes and Infection / Institut Pasteur 5 (6): 553–60. PMID 12758285.

- ↑ Shors pp. 76–77

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Collier p. 3

- ↑ Dimmock p.4–5

- ↑ Shors p. 589

- ↑ D'Herelle F (September 2007). "On an invisible microbe antagonistic toward dysenteric bacilli": brief note by Mr. F. D'Herelle, presented by Mr. Roux. 1917. Res. Microbiol. 158(7):553–4. Epub 2007 Jul 28. PMID 17855060

- ↑ Steinhardt, E; Israeli, C; and Lambert, R.A. (1913) "Studies on the cultivation of the virus of vaccinia" J. Inf Dis. 13, 294–300

- ↑ Collier p. 4

- ↑ Goodpasture EW, Woodruff AM, Buddingh GJ (1931). "The cultivation of vaccine and other viruses in the chorioallantoic membrane of chick embryos". Science 74, pp. 371–372 PMID 17810781

- ↑ Rosen FS (2004). "Isolation of poliovirus—John Enders and the Nobel Prize". New England Journal of Medicine, 351, pp. 1481–83 PMID 15470207

- ↑ From Nobel Lectures, Physics 1981–1990, (1993) Editor-in-Charge Tore Frängsmyr, Editor Gösta Ekspång, World Scientific Publishing Co., Singapore.

- In 1887, Buist visualised one of the largest, Vaccinia virus, by optical microscopy after staining it. Vaccinia was not known to be a virus at that time. (Buist J.B. Vaccinia and Variola: a study of their life history Churchill, London)

- ↑ Stanley WM, Loring HS (1936). "The isolation of crystalline tobacco mosaic virus protein from diseased tomato plants". Science, 83, p.85 PMID 17756690

- ↑ Stanley WM, Lauffer MA (1939). "Disintegration of tobacco mosaic virus in urea solutions". Science 88, pp. 345–347 PMID 17788438

- ↑ Creager AN, Morgan GJ. After the double helix: Rosalind Franklin's research on Tobacco mosaic virus. Isis. 2008 [cited 16 September 2008];99(2):239–72. doi:10.1086/588626. PMID 18702397.

- ↑ Dimmock p. 12

- ↑ Norrby E. Nobel Prizes and the emerging virus concept. Arch. Virol.. 2008;153(6):1109–23. doi:10.1007/s00705-008-0088-8. PMID 18446425.

- ↑ ICTV list of virus discoveries and discoverers

- ↑ Collier p. 745

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Temin HM, Baltimore D. RNA-directed DNA synthesis and RNA tumor viruses. Adv. Virus Res.. 1972 [cited 16 September 2008];17:129–86. doi:10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60749-6. PMID 4348509.

- ↑ Barré-Sinoussi, F., Chermann, J. C., Rey, F., Nugeyre, M. T., Chamaret, S., Gruest, J., Dauguet, C., Axler-Blin, C., Vezinet-Brun, F., Rouzioux, C., Rozenbaum, W., and Montagnier, L.. Isolation of a T-lymphotropic retrovirus from a patient at risk for acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Science. 1983;220(4599):868–871. doi:10.1126/science.6189183. PMID 6189183.

- ↑ Iyer LM, Balaji S, Koonin EV, Aravind L. Evolutionary genomics of nucleo-cytoplasmic large DNA viruses. Virus Res.. 2006 [cited 14 September 2008];117(1):156–84. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2006.01.009. PMID 16494962.

- ↑ Liu Y, Nickle DC, Shriner D, et al. (2004). "Molecular clock-like evolution of human immunodeficiency virus type 1". Virology. 10;329(1):101–8, PMID 15476878

- ↑ Shors p. 16

- ↑ Collier pp. 18–19

- ↑ Shors pp. 14–16

- ↑ Collier pp. 11–21

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Dimmock p. 16

- ↑ Collier p. 11

- ↑ Shors p. 574

- ↑ The origin and behavior of mutable loci in maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.. 1950;36(6):344–55. doi:10.1073/pnas.36.6.344. PMID 15430309.

- ↑ Collier pp. 11–12

- ↑ Dimmock p. 55

- ↑ Shors 551–3

- ↑ Tsagris EM, de Alba AE, Gozmanova M, Kalantidis K. Viroids. Cell. Microbiol.. 2008 [cited 19 September 2008];10(11):2168. doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01231.x. PMID 18764915.

- ↑ Shors p. 492–3

- ↑ La Scola B, Desnues C, Pagnier I, Robert C, Barrassi L, Fournous G, Merchat M, Suzan-Monti M, Forterre P, Koonin E, Raoult D. The virophage as a unique parasite of the giant mimivirus. Nature. 2008 [cited 20 January 2009];455(7209):100–4. doi:10.1038/nature07218. PMID 18690211.

- ↑ Collier p. 777

- ↑ Dimmock p. 55–7

- ↑ Liberski PP. Prion diseases: a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma. Folia Neuropathol. 2008 [cited 19 September 2008];46(2):93–116. PMID 18587704.

- ↑ Dimmock pp. 57–58

- ↑ Lupi O, Dadalti P, Cruz E, Goodheart C. Did the first virus self-assemble from self-replicating prion proteins and RNA?. Med. Hypotheses. 2007 [cited 19 September 2008];69(4):724–30. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2007.03.031. PMID 17512677.

- ↑ Dimmock pp. 15–16

- ↑ Rybicki EP (1990) "The classification of organisms at the edge of life, or problems with virus systematics." S Aft J Sci 86:182–186

- ↑ Holmes EC. Viral evolution in the genomic age. PLoS Biol.. 2007 [cited 13 September 2008];5(10):e278. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050278. PMID 17914905. PMC 1994994.

- ↑ Wimmer E, Mueller S, Tumpey TM, Taubenberger JK. Synthetic viruses: a new opportunity to understand and prevent viral disease. Nature Biotechnology. 2009;27(12):1163–72. doi:10.1038/nbt.1593. PMID 20010599.

- ↑ Horn M. Chlamydiae as symbionts in eukaryotes. Annual Review of Microbiology. 2008;62:113–31. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162818. PMID 18473699.

- ↑ Ammerman NC, Beier-Sexton M, Azad AF. Laboratory maintenance of Rickettsia rickettsii. Current Protocols in Microbiology. 2008;Chapter 3:Unit 3A.5. doi:10.1002/9780471729259.mc03a05s11. PMID 19016440.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Collier pp. 33–55

- ↑ Collier pp. 33–37

- ↑ Kiselev NA, Sherman MB, Tsuprun VL. Negative staining of proteins. Electron Microsc. Rev.. 1990;3(1):43–72. doi:10.1016/0892-0354(90)90013-I. PMID 1715774.

- ↑ Collier p. 40

- ↑ Caspar DL, Klug A. Physical principles in the construction of regular viruses. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol.. 1962;27:1–24. PMID 14019094.

- ↑ Crick FH, Watson JD. Structure of small viruses. Nature. 1956;177(4506):473–5. doi:10.1038/177473a0. PMID 13309339.

- ↑ Manipulation of individual viruses: friction and mechanical properties. Biophysical Journal. March 1997 [cited 8 May 2009];72(3):1396–1403. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78786-1. PMID 9138585. PMC 1184522.

- ↑ Imaging of viruses by atomic force microscopy. J Gen Virol. 1 September 2001 [cited 19 April 2009];82(9):2025–2034.

- ↑ Collier p. 37

- ↑ Collier pp. 40, 42

- ↑ Collier pp. 42–43

- ↑ Rossmann MG, Mesyanzhinov VV, Arisaka F, Leiman PG. The bacteriophage T4 DNA injection machine. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol.. 2004;14(2):171–80. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2004.02.001. PMID 15093831.

- ↑ Long GW, Nobel J, Murphy FA, Herrmann KL, Lourie B. Experience with electron microscopy in the differential diagnosis of smallpox. Appl Microbiol. 1970;20(3):497–504. PMID 4322005.

- ↑ Suzan-Monti M, La Scola B, Raoult D. Genomic and evolutionary aspects of Mimivirus. Virus Research. 2006;117(1):145–155. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2005.07.011. PMID 16181700.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Prangishvili D, Forterre P, Garrett RA. Viruses of the Archaea: a unifying view. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.. 2006;4(11):837–48. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1527. PMID 17041631.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 74.3 Collier pp. 96–99

- ↑ Pressing J, Reanney DC (1984). "Divided genomes and intrinsic noise". J Mol Evol. 20(2):135–46.

- ↑ Pan XP, Li LJ, Du WB, Li MW, Cao HC, Sheng JF. Differences of YMDD mutational patterns, precore/core promoter mutations, serum HBV DNA levels in lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B genotypes B and C. J. Viral Hepat.. 2007 [cited 13 September 2008];14(11):767–74. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00869.x. PMID 17927612.

- ↑ Hampson AW, Mackenzie JS. The influenza viruses. Med. J. Aust.. 2006 [cited 13 September 2008];185(10 Suppl):S39–43. PMID 17115950.

- ↑ Metzner KJ. Detection and significance of minority quasispecies of drug-resistant HIV-1. J HIV Ther. 2006;11(4):74–81. PMID 17578210.

- ↑ Goudsmit, Jaap. Viral Sex. Oxford Univ Press, 1998.ISBN 978-0-19-512496-5 ISBN 0-19-512496-0

- ↑ Worobey M, Holmes EC. Evolutionary aspects of recombination in RNA viruses. J. Gen. Virol.. 1999;80 ( Pt 10):2535–43. PMID 10573145.

- ↑ Lukashev AN. Role of recombination in evolution of enteroviruses. Rev. Med. Virol.. 2005;15(3):157–67. doi:10.1002/rmv.457. PMID 15578739.

- ↑ Umene K. Mechanism and application of genetic recombination in herpesviruses. Rev. Med. Virol.. 1999;9(3):171–82. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1654(199907/09)9:3<171::AID-RMV243>3.0.CO;2-A. PMID 10479778.

- ↑ Collier pp. 75–91

- ↑ Dimmock p. 70

- ↑ Boevink P, Oparka KJ. Virus-host interactions during movement processes. Plant Physiol.. 2005;138(4):1815–21. doi:10.1104/pp.105.066761. PMID 16172094. PMC 1183373.

- ↑ Dimmock p. 71

- ↑ Barman S, Ali A, Hui EK, Adhikary L, Nayak DP. Transport of viral proteins to the apical membranes and interaction of matrix protein with glycoproteins in the assembly of influenza viruses. Virus Res.. 2001;77(1):61–9. doi:10.1016/S0168-1702(01)00266-0. PMID 11451488.

- ↑ Shors pp. 60, 597

- ↑ Dimmock, Chapter 15, Mechanisms in virus latentcy, pp.243–259

- ↑ Dimmock 185–187

- ↑ Shors p. 54; Collier p. 78

- ↑ Collier p. 79

- ↑ Collier pp. 88–89

- ↑ Collier pp. 115–146

- ↑ Collier p. 115

- ↑ Roulston A, Marcellus RC, Branton PE. Viruses and apoptosis. Annu. Rev. Microbiol.. 1999 [cited 20 December 2008];53:577–628. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.53.1.577. PMID 10547702.

- ↑ Alwine JC. Modulation of host cell stress responses by human cytomegalovirus. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol.. 2008 [cited 20 December 2008];325:263–79. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-77349-8_15. PMID 18637511.

- ↑ Sinclair J. Human cytomegalovirus: Latency and reactivation in the myeloid lineage. J. Clin. Virol.. 2008 [cited 20 December 2008];41(3):180–5. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2007.11.014. PMID 18164651.

- ↑ Jordan MC, Jordan GW, Stevens JG, Miller G. Latent herpesviruses of humans. Ann. Intern. Med.. 1984 [cited 20 December 2008];100(6):866–80. PMID 6326635.

- ↑ Sissons JG, Bain M, Wills MR. Latency and reactivation of human cytomegalovirus. J. Infect.. 2002 [cited 20 December 2008];44(2):73–7. doi:10.1053/jinf.2001.0948. PMID 12076064.

- ↑ Barozzi P, Potenza L, Riva G, Vallerini D, Quadrelli C, Bosco R, Forghieri F, Torelli G, Luppi M. B cells and herpesviruses: a model of lymphoproliferation. Autoimmun Rev. 2007 [cited 20 December 2008];7(2):132–6. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2007.02.018. PMID 18035323.

- ↑ Subramanya D, Grivas PD. HPV and cervical cancer: updates on an established relationship. Postgrad Med. 2008 [cited 20 December 2008];120(4):7–13. doi:10.3810/pgm.2008.11.1928. PMID 19020360.

- ↑ Shors p. 388

- ↑ Shors p. 353

- ↑ Dimmock p. 272

- ↑ Baggesen DL, Sørensen G, Nielsen EM, Wegener HC. Phage typing of Salmonella Typhimurium - is it still a useful tool for surveillance and outbreak investigation?. Euro Surveillance : Bulletin Européen Sur Les Maladies Transmissibles = European Communicable Disease Bulletin. 2010;15(4):19471. PMID 20122382.

- ↑ Lwoff A, Horne RW, Tournier P. A virus system. C. R. Hebd. Seances Acad. Sci.. 1962;254:4225–7. French. PMID 14467544.

- ↑ Lwoff A, Horne R, Tournier P. A system of viruses. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol.. 1962;27:51–5. PMID 13931895.

- ↑ Fields p. 27

- As defined therein, "a virus species is a polythetic class of viruses that constitute a replicating lineage and occupy a particular ecological niche". A “polythetic" class is one whose members have several properties in common, although they do not necessarily all share a single common defining one. Members of a virus species are defined collectively by a consensus group of properties. Virus species thus differ from the higher viral taxa, which are “universal” classes and as such are defined by properties that are necessary for membership.

- ↑ Delwart EL. Viral metagenomics. Rev. Med. Virol.. 2007;17(2):115–31. doi:10.1002/rmv.532. PMID 17295196.

- ↑ Virus Taxonomy 2008. International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Retrieved on September 15, 2008.

- ↑ ICTV Master Species List 2008

- This Excel file contains the official ICTV Master Species list for 2008. This spreadsheet lists all approved virus taxa and supersedes the previous taxonomy published as a part of the ICTV VIIIth Report. Produced by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Retrieved on September 15, 2008

- ↑ Baltimore D. The strategy of RNA viruses. Harvey Lect.. 1974;70 Series:57–74. PMID 4377923.

- ↑ van Regenmortel MH, Mahy BW. Emerging issues in virus taxonomy. Emerging Infect. Dis.. 2004;10(1):8–13. PMID 15078590.

- ↑ Mayo MA. Developments in plant virus taxonomy since the publication of the 6th ICTV Report. International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Arch. Virol.. 1999;144(8):1659–66. doi:10.1007/s007050050620. PMID 10486120.

- ↑ de Villiers EM, Fauquet C, Broker TR, Bernard HU, zur Hausen H. Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology. 2004;324(1):17–27. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2004.03.033. PMID 15183049.

- ↑ Mainly Chapter 33 (Disease summaries), pages 367–392 in:Fisher, Bruce; Harvey, Richard P.; Champe, Pamela C.. Lippincott's Illustrated Reviews: Microbiology (Lippincott's Illustrated Reviews Series). Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. ISBN 0-7817-8215-5. p. pages 367–392.|alt=A photograph of the upper body of a man labelled with the names of viruses that infect the different parts

- ↑ For common cold: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) > Common Cold. Last Updated December 10, 2007. Retrieved on 4 April 2009

- ↑ Komaroff AL. Is human herpesvirus-6 a trigger for chronic fatigue syndrome?. J. Clin. Virol.. 2006;37 Suppl 1:S39–46. doi:10.1016/S1386-6532(06)70010-5. PMID 17276367.

- ↑ Chen C, Chiu Y, Wei F, Koong F, Liu H, Shaw C, Hwu H, Hsiao K. High seroprevalence of Borna virus infection in schizophrenic patients, family members and mental health workers in Taiwan. Mol Psychiatry. 1999;4(1):33–8. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4000484. PMID 10089006.

- ↑ Margolis TP, Elfman FL, Leib D, et al.. Spontaneous reactivation of herpes simplex virus type 1 in latently infected murine sensory ganglia. J. Virol.. 2007 [cited 13 September 2008];81(20):11069–74. doi:10.1128/JVI.00243-07. PMID 17686862. PMC 2045564.

- ↑ Whitley RJ, Roizman B. Herpes simplex virus infections. Lancet. 2001;357(9267):1513–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04638-9. PMID 11377626.

- ↑ Barton ES, White DW, Cathelyn JS, et al.. Herpesvirus latency confers symbiotic protection from bacterial infection. Nature. 2007;447(7142):326–9. doi:10.1038/nature05762. PMID 17507983.

- ↑ Bertoletti A, Gehring A. Immune response and tolerance during chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatol. Res.. 2007;37 Suppl 3:S331–8. doi:10.1111/j.1872-034X.2007.00221.x. PMID 17931183.

- ↑ Rodrigues C, Deshmukh M, Jacob T, Nukala R, Menon S, Mehta A. Significance of HBV DNA by PCR over serological markers of HBV in acute and chronic patients. Indian journal of medical microbiology. 2001;19(3):141–4. PMID 17664817.

- ↑ Nguyen VT, McLaws ML, Dore GJ. Highly endemic hepatitis B infection in rural Vietnam. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2007;22(12):2093–100. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05010.x. PMID 17645465.

- ↑ Witzany G (2006) "Natural Genome-Editing Competences of Viruses'" Acta Biotheor 54: 235–253.

- ↑ Fowler MG, Lampe MA, Jamieson DJ, Kourtis AP, Rogers MF. Reducing the risk of mother-to-child human immunodeficiency virus transmission: past successes, current progress and challenges, and future directions. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol.. 2007;197(3 Suppl):S3–9. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2007.06.048. PMID 17825648.

- ↑ Sauerbrei A, Wutzler P. The congenital varicella syndrome. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association. 2000;20(8 Pt 1):548–54. PMID 11190597.

- ↑ Garnett GP. Role of herd immunity in determining the effect of vaccines against sexually transmitted disease. J. Infect. Dis.. 2005 [cited 13 September 2008];191 Suppl 1:S97–106. doi:10.1086/425271. PMID 15627236.

- ↑ Platonov AE. (The influence of weather conditions on the epidemiology of vector-borne diseases by the example of West Nile fever in Russia). Vestn. Akad. Med. Nauk SSSR. 2006;(2):25–9. Russian. PMID 16544901.

- ↑ Shors p. 198

- ↑ Shors pp. 199, 209

- ↑ Shors p. 19

- ↑ Shors p. 126

- ↑ Shors pp. 193–194

- ↑ Shors pp. 193–94

- ↑ Shors p. 194