Nattō

Nattō (なっとう or 納豆) is a traditional Japanese food made from soybeans fermented with Bacillus subtilis. It is popular especially as a breakfast food. As a rich source of protein, nattō and the soybean paste miso formed a vital source of nutrition in feudal Japan. Nattō can be an acquired taste because of its powerful smell, strong flavor, and slippery texture. In Japan nattō is most popular in the eastern regions, including Kantō, Tōhoku, and Hokkaido.

Many countries produce similar traditional soybean foods fermented with Bacillus subtilis, such as shuǐdòuchǐ (水豆豉) of China, cheonggukjang (청국장) of Korea, thua nao of Thailand, kinema of Nepal and the Himalayan regions of West Bengal and Sikkim, India.[1] In addition certain West African bean products are fermented with the bacillus, including dawadawa, sumbala, and iru, made from néré seeds or soybeans, and ogiri, made from sesame or melon seeds.

Contents |

History

Sources differ about the earliest origin of nattō. The materials and tools needed to produce nattō have been commonly available in Japan since ancient times; one source puts the first use of nattō in the Jōmon period (10,000–300 BC). According to other sources the product may have originated in China during the Zhou Dynasty (1134-246 BC). There is also the story about Minamoto no Yoshiie who was on a battle campaign in northeastern Japan between 1086 and 1088 when one day they were attacked while boiling soybeans for their horses. They hurriedly packed up the beans, and did not open the straw bags until a few days later, by which time the beans had fermented. The soldiers ate it anyway, and liked the taste, so they offered some to Yoshiie, who also liked the taste. A third source places the origin of nattō more recently, in the Edo period (1603–1867). It is even possible that the product was discovered independently by numerous people at different times.

One significant change in the production of nattō happened in the Taishō period (1912–1926), when researchers discovered a way to produce a nattō starter culture containing Bacillus natto without the need for straw. This greatly simplified the production process and permitted more consistent results.

Appearance and consumption

The first thing noticed by the uninitiated after opening a pack of nattō is its distinctive smell, somewhat akin to a pungent cheese. Stirring the nattō produces lots of sticky gossamer-like strings. The nattō strings themselves are often described by the Japanese ideophone nebaneba, which roughly translates as 'viscid' or 'gooey'. The flavor of nattō is nutty, savory, and slightly salty.

Nattō is most commonly eaten at breakfast to accompany rice, possibly with some other ingredients, for example soy sauce, tsuyu broth, mustard, scallions, grated daikon, okra, or a raw quail egg. In Hokkaidō and northern Tohoku region, some people dust nattō with sugar. Nattō is also commonly used in other foods, such as nattō sushi, nattō toast, in miso soup, salad, as an ingredient in okonomiyaki, or even with spaghetti or as fried nattō. A dried form of nattō, having little odor or sliminess, can be eaten as a nutritious snack. There is even nattō ice cream.

Nattō is often considered an acquired taste and the perceived flavor of nattō can differ greatly between people; some find it tastes very strong and cheesy and may use it in small amounts to flavor rice or noodles, while others find it tastes bland and unremarkable [1], requiring the addition of flavoring condiments such as mustard and soy sauce. Many non-Japanese find the taste very unpleasant, while others relish it as a delicacy. Some manufacturers produce an odorless or low-odor nattō. The split opinion about its appearance and taste might be compared to Vegemite in Australia, blue cheese in France, surströmming in Sweden, lutefisk in Norway and Sweden, mämmi in Finland and Marmite in New Zealand, South Africa and the UK. Even in Japan, nattō is more popular in some areas than in others. Nattō is known to be popular in the eastern Kantō region (Tokyo), but less popular in Kansai (Osaka, Kobe). About 236,000 tons of nattō are consumed in Japan each year.

Production process

Nattō is made from soybeans, typically a special type called nattō soybeans. Smaller beans are preferred, as the fermentation process will be able to reach the center of the bean more easily. The beans are washed and soaked in water for 12 to 20 hours to increase their size. Next, the soybeans are steamed for 6 hours, although a pressure cooker can be used to reduce the time. The beans are mixed with the bacterium Bacillus subtilis natto, known as nattō-kin in Japanese. From this point on, care has to be taken to keep the ingredients away from impurities and other bacteria. The mixture is fermented at 40°C for up to 24 hours. Afterwards the nattō is cooled, then aged in a refrigerator for up to one week to allow the development of stringiness. During the aging process, at a temperature of about 0°C, the bacilli develop spores, and enzymatic peptidases break down the soybean protein into its constituent amino acids.

Historically, nattō was made by storing the steamed soybeans in rice straw, which naturally contains B. subtilis natto. The soybeans were packed in straw and then left to ferment. The fermentation was done either while the beans were buried underground underneath a fire or stored in a warm place in the house, for example under the kotatsu.

End product

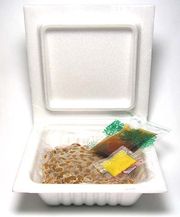

Today's mass-produced nattō is usually sold in small polystyrene containers. A typical package contains 2 or 3 containers, occasionally 4 containers, each of 40 to 50 g. One container typically complements a small bowl of rice. It usually includes a small packet of soy sauce and another packet of karashi, a type of mustard. Other flavors of sauce, such as shiso, are available.

Mito City and Kumamoto Prefecture are major nattō-producing areas.

Outside Japan nattō is sometimes sold frozen and must be thawed before consumption.

Medical benefits

The Japanese media frequently claim, especially in television shows for health-obsessive viewers, that nattō is health-enhancing and that these claims are backed by medical research.

One example is pyrazine: Pyrazine is a compound that, in addition to giving nattō its distinct smell, reduces the likelihood of blood clotting. It also contains a serine protease type enzyme called nattokinase[2] which may also reduce blood clotting both by direct fibrinolysis of clots, and inhibition of the plasma protein plasminogen activator inhibitor 1. This may help to avoid thrombosis, as for example in heart attacks, pulmonary embolism, or strokes.

An extract from nattō containing nattokinase is available as a dietary supplement. Studies have shown that oral administration of nattokinase in enteric capsules leads to a mild enhancement of fibrinolytic activity in rats[3] and dogs. It is, therefore, plausible to hypothesize that nattokinase might reduce blood clots in humans—although clinical trials have not been conducted. Another study suggests the FAS in natto is the substance which initiates fibrinolysis of clots, which accelerates the activity of not only nattokinase but urokinase.[4]

A 2009 study in Taiwan indicated that the nattokinase in natto has the ability to degrade amyloid fibrils, suggesting that it might be a preventative or a treatment for amyloid-type diseases such as Alzheimer's.[5]

Nattō contains large amounts of vitamin K, which is involved in the formation of calcium-binding groups in proteins, assisting the formation of bone and preventing osteoporosis. Vitamin K1 is found naturally in seaweed, liver, and some vegetables, while vitamin K2 is found in fermented food products such as cheese and miso. Nattō has very large amounts of vitamin K2, approximately 870 micrograms per 100 grams of nattō.

According to a study, fermented soybeans, such as nattō, contain vitamin PQQ, which is very important for the skin.[6] PQQ in human tissues is derived mainly from diet.

According to recent studies, polyamine suppresses excessive immune reactions, and nattō has a much larger amount of it than any other food.[7] Dietary supplements containing the substances extracted from natto such as polyamine, nattokinase, FAS and vitamin K2 are available.

Nattō contains many chemicals alleged to prevent cancer, for example, daidzein, genistein, isoflavone, phytoestrogen, and the chemical element selenium. However, most of these chemicals can also be found in other soybean products, and their effect on cancer prevention is uncertain at best.

Recent studies show nattō may have a cholesterol-lowering effect.[8]

Nattō is also said to have an antibiotic effect, and its use as medicine against dysentery was researched by the Imperial Japanese Navy before World War II.[9]

Nattō is claimed to prevent obesity, possibly because of its low calorie content of approximately 90 calories per 7–8 grams of protein in an average serving. Unverified claims include improved digestion, reduced effects of aging, and the reversal of hair loss in men due to its phytoestrogen content, which can affect testosterone associated with baldness. These conjectured physiological effects of eating natto are based on biochemically active contents of nattō, and have not been confirmed by human study.

Nattō is also sometimes used as an ingredient of pet food, and it is claimed that this improves the health of the pets.[10]

Gallery

A nattō bean-size legend using beans before fermentation in a supermarket |

Natto is marketed in many ways: This packet includes collagen |

See also

Other fermented soy foods include soy sauce, Japanese miso, Chinese dòuchǐ (fermented black beans) and chòu dòufu (stinky tofu), Korean doenjang and cheonggukjang, and Indonesian tempeh.

- Fermented bean paste

Note that amanattō is not nattō but, rather, beans sweetened with sugar.

References

- ↑ Arora, Ajello, Mukerji, et al. (1991). Handbook of Applied Mycology. CRC Press. p. 332. ISBN 082478491X.,

- ↑ Fujita M et al. (December 1993). "Purification and characterization of a strong fibrinolytic enzyme (nattokinase) in the vegetable cheese natto, a popular soybean fermented food in Japan". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 197 (3): 1340–1347. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1993.2624. PMID 8280151.

- ↑ Fujita M, Hong K, Ito Y, Misawa S, Takeuchi N, Kariya K, Nishimuro S. (September 1995). "Transport of nattokinase across the rat intestinal tract". Biological & pharmaceutical bulletin. 18 (9): 1194–1196. PMID 8845803.

- ↑ Hiroyuki Sumi et al. (November 2000). "Determination and Properties of the Fibrinolysis Accelerating Substance(FAS) in Japanese Fermented Soybean "Natto"". Nippon Nogeikagaku Kaishi(Japanese). 74 (11): 1259–1264.

- ↑ Soy Product Fights Abnormal Protein in Alzheimer's Disease

- ↑ T Kumazawa, K Sato, H Seno, A Ishii, O Suzuki (April 1, 1995). "Levels of pyrroloquinoline quinone in various foods". Biochem. J. 307 (Pt 2): 331–333. PMID 7733865. PMC 1136652. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1136652. Retrieved 2007-10-20.

- ↑ Kuniyasu Soda, Yoshihiko Kano, Takeshi Nakamura, Keizo Kasono, Masanobu Kawakami and Fumio Konishi (July 2005). "Spermine, a natural polyamine, suppresses LFA-1 expression on human lymphocyte". The Journal of Immunology. 175 (1): 237–45. PMID 15972654.

- ↑ National Cardiovascular Center (Suita, Osaka, Japan) HuBit genomix, Inc. (Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, Japan; President and CEO: Go Ichien) NTT DATA Corporation (Koto-ku, Tokyo, Japan; President and CEO: Tomokazu Hamaguchi) Municipality of Arita, Saga Prefecture, Japan (Mayor: Masata Iwanaga) (April 2006). "Examining the Effects of Natto (fermented soybean) Consumption on Lifestyle-Related Diseases". http://www.nttdata.co.jp/en/media/2006/042700.html. Retrieved 2007-03-19.

- ↑ 有馬玄 (1937). "納豆菌ト赤痢菌トノ拮抗作用ニ関スル実験的研究(第2報)動物体内ニ於ケル納豆菌と志賀菌トノ拮抗作用". 海軍軍医誌 26: 398–419.

- ↑ "ドットわんフリーズドライ納豆". http://www.purebox.jp/dwfd/nattou/index.html. Retrieved 2007-03-20.

External links

- Natto for Everybody Homepage

- Nutrition facts of natto

- A video demonstrating how to consume natto

- Goku Kotsubu Mini 3-Inch Natto (dietfacts.com)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||