NATO

| North Atlantic Treaty Organization Organisation du Traité de l'Atlantique Nord (NATO / OTAN) |

|

|---|---|

Flag of NATO[1] |

|

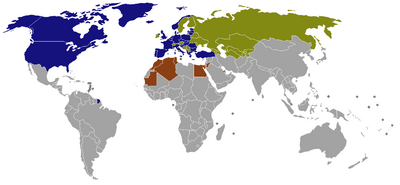

.svg.png) NATO countries shown in green. |

|

| Formation | 4 April 1949 |

| Type | Military alliance |

| Headquarters | Brussels, Belgium |

| Membership | |

| Official languages | English French[2] |

| Secretary General | Anders Fogh Rasmussen |

| Chairman of the NATO Military Committee | Giampaolo Di Paola |

| Website | nato.int |

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization or NATO (pronounced /ˈneɪtoʊ/ NAY-toe; French: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique Nord (OTAN)), also called the "(North) Atlantic Alliance", is an intergovernmental military alliance based on the North Atlantic Treaty which was signed on 4 April 1949. The NATO headquarters are in Brussels, Belgium,[3] and the organization constitutes a system of collective defence whereby its member states agree to mutual defence in response to an attack by any external party.

For its first few years, NATO was not much more than a political association. However, the Korean War galvanized the member states, and an integrated military structure was built up under the direction of two U.S. supreme commanders. The first NATO Secretary General, Lord Ismay, famously stated the organization's goal was "to keep the Russians out, the Americans in, and the Germans down".[4] Doubts over the strength of the relationship between the European states and the United States ebbed and flowed, along with doubts over the credibility of the NATO defence against a prospective Soviet invasion—doubts that led to the development of the independent French nuclear deterrent and the withdrawal of the French from NATO's military structure from 1966.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the organization became drawn into the Balkans while building better links with former potential enemies to the east, which culminated with several former Warsaw Pact states joining the alliance in 1999 and 2004. On 1 April 2009, membership was enlarged to 28 with the entrance of Albania and Croatia.[5] Since the 11 September attacks, NATO has attempted to refocus itself to new challenges and has deployed troops to Afghanistan as well as trainers to Iraq.

The Berlin Plus agreement is a comprehensive package of agreements made between NATO and the European Union on 16 December 2002. With this agreement the EU was given the possibility to use NATO assets in case it wanted to act independently in an international crisis, on the condition that NATO itself did not want to act—the so-called "right of first refusal".[6] Only if NATO refused to act would the EU have the option to act. The combined military spending of all NATO members constitutes over 70% of the world's defence spending.[7] The United States alone accounts for 43% of the total military spending of the world[8] and the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Italy account for a further 15%.[7]

Contents |

History

Beginnings

The Treaty of Brussels, signed on 17 March 1948 by Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, France and the United Kingdom is considered the precursor to the NATO agreement. The treaty and the Soviet Berlin Blockade led to the creation of the Western European Union's Defence Organization in September 1948.[9] However, participation of the United States was thought necessary in order to counter the military power of the USSR, and therefore talks for a new military alliance began almost immediately.

These talks resulted in the North Atlantic Treaty, which was signed in Washington, D.C. on 4 April 1949. It included the five Treaty of Brussels states, as well as the United States, Canada, Portugal, Italy, Norway, Denmark and Iceland. Popular support for the Treaty was not unanimous; some Icelanders commenced a pro-neutrality, anti-membership riot in March 1949.

| “ | The Parties of NATO agreed that an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America[10] shall be considered an attack against them all. Consequently they agree that, if such an armed attack occurs, each of them, in exercise of the right of individual or collective self-defence will assist the Party or Parties being attacked, individually and in concert with the other Parties, such action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force, to restore and maintain the security of the North Atlantic area. | ” |

Such action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force does not necessarily mean that other member states will respond with military action against the aggressor(s). Rather they are obliged to respond, but maintain the freedom to choose how they will respond. This differs from Article IV of the Treaty of Brussels (which founded the Western European Union) which clearly states that the response however often assumed that NATO members will aid the attacked member militarily. Further, the article limits the organization's scope to regions above the Tropic of Cancer,[10] which explains why the Falklands War did not result in NATO involvement.

The creation of NATO brought about some standardization of allied military terminology, procedures, and technology, which in many cases meant European countries adopting U.S. practices. The roughly 1300 Standardization Agreements (STANAGs) codifies the standardization that NATO has achieved. Hence, the 7.62×51 NATO rifle cartridge was introduced in the 1950s as a standard firearm cartridge among many NATO countries. Fabrique Nationale de Herstal's FAL became the most popular 7.62 NATO rifle in Europe and served into the early 1990s. Also, aircraft marshalling signals were standardized, so that any NATO aircraft could land at any NATO base. Other standards such as the NATO phonetic alphabet have made their way beyond NATO into civilian use.

Cold War

The outbreak of the Korean War in 1950 was crucial for NATO as it raised the apparent threat level greatly (all Communist countries were suspected of working together) and forced the alliance to develop concrete military plans.[11] The 1952 Lisbon conference, seeking to provide the forces necessary for NATO's Long-Term Defence Plan, called for an expansion to 96 divisions. However this requirement was dropped the following year to roughly 35 divisions with heavier use to be made of nuclear weapons. At this time, NATO could call on about 15 ready divisions in Central Europe, and another ten in Italy and Scandinavia.[12] Also at Lisbon, the post of Secretary General of NATO as the organization's chief civilian was also created, and Baron Hastings Ismay eventually appointed to the post.[13] Later, in September 1952, the first major NATO maritime exercises began; Operation Mainbrace brought together 200 ships and over 50,000 personnel to practice the defence of Denmark and Norway.

Greece and Turkey joined the alliance the same year, forcing a series of controversial negotiations, in which the United States and Britain were the primary disputants, over how to bring the two countries into the military command structure.[14] Meanwhile, while this overt military preparation was going on, covert stay-behind arrangements to continue resistance after a successful Soviet invasion ('Operation Gladio'), initially made by the Western European Union, were being transferred to NATO control. Ultimately unofficial bonds began to grow between NATO's armed forces, such as the NATO Tiger Association and competitions such as the Canadian Army Trophy for tank gunnery.

In 1954, the Soviet Union suggested that it should join NATO to preserve peace in Europe.[15] The NATO countries, fearing that the Soviet Union's motive was to weaken the alliance, ultimately rejected this proposal. The incorporation of West Germany into the organization on 9 May 1955 was described as "a decisive turning point in the history of our continent" by Halvard Lange, Foreign Minister of Norway at the time.[16] A major reason for Germany's entry into the alliance was that without German manpower, it would have been impossible to field enough conventional forces to resist a Soviet invasion.[17] Indeed, one of its immediate results was the creation of the Warsaw Pact, signed on 14 May 1955 by the Soviet Union, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Bulgaria, Romania, Albania, and East Germany, as a formal response to this event, thereby delineating the two opposing sides of the Cold War.

French withdrawal

The unity of NATO was breached early in its history, with a crisis occurring during Charles de Gaulle's presidency of France from 1958 onwards. De Gaulle protested at the United States' strong role in the organization and what he perceived as a special relationship between the United States and the United Kingdom. In a memorandum sent to President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Prime Minister Harold Macmillan on 17 September 1958, he argued for the creation of a tripartite directorate that would put France on an equal footing with the United States and the United Kingdom, and also for the expansion of NATO's coverage to include geographical areas of interest to France, most notably French Algeria, where France was waging a counter-insurgency and sought NATO assistance.

Considering the response given to be unsatisfactory, de Gaulle began to build an independent defence for his country. He also wanted to give France, in the event of an East German incursion into West Germany, the option of coming to a separate peace with the Eastern bloc instead of being drawn into a NATO-Warsaw Pact global war. On 11 March 1959, France withdrew its Mediterranean Fleet from NATO command; three months later, in June 1959, de Gaulle banned the stationing of foreign nuclear weapons on French soil. This caused the United States to transfer two hundred military aircraft out of France and return control of the ten major air force bases that had operated in France since 1950 to the French by 1967.

Though France showed solidarity with the rest of NATO during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, de Gaulle continued his pursuit of an independent defence by removing France's Atlantic and Channel fleets from NATO command. In 1966, all French armed forces were removed from NATO's integrated military command, and all non-French NATO troops were asked to leave France. This withdrawal forced the relocation of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE) from Rocquencourt, near Paris, to Casteau, north of Mons, Belgium, by 16 October 1967. France remained a member of the alliance, and committed to the defence of Europe from possible Communist attack with its own forces stationed in the Federal Republic of Germany throughout the Cold War. A series of secret accords between U.S. and French officials, the Lemnitzer-Ailleret Agreements, detailed how French forces would dovetail back into NATO's command structure should East-West hostilities break out.[18]

Détente

During most of the Cold War, NATO maintained a holding pattern with no actual military engagement as an organization. On 1 July 1968, the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty opened for signature: NATO argued that its nuclear sharing arrangements did not breach the treaty as U.S. forces controlled the weapons until a decision was made to go to war, at which point the treaty would no longer be controlling. Few states knew of the NATO nuclear sharing arrangements at that time, and they were not challenged.

On 30 May 1978, NATO countries officially defined two complementary aims of the Alliance, to maintain security and pursue détente. This was supposed to mean matching defences at the level rendered necessary by the Warsaw Pact's offensive capabilities without spurring a further arms race.

On 12 December 1979, in light of a build-up of Warsaw Pact nuclear capabilities in Europe, ministers approved the deployment of U.S. GLCM cruise missiles and Pershing II theatre nuclear weapons in Europe. The new warheads were also meant to strengthen the western negotiating position regarding nuclear disarmament. This policy was called the Dual Track policy. Similarly, in 1983–84, responding to the stationing of Warsaw Pact SS-20 medium-range missiles in Europe, NATO deployed modern Pershing II missiles tasked to hit military targets such as tank formations in the event of war. This action led to peace movement protests throughout Western Europe.

Escalation

With the background of the build-up of tension between the Soviet Union and the United States, NATO decided, under the impetus of the Reagan presidency, to deploy Pershing II and cruise missiles in Western Europe, primarily West Germany. These missiles were theatre nuclear weapons intended to strike targets on the battlefield if the Soviets invaded West Germany. Yet support for the deployment was wavering and many doubted whether the push for deployment could be sustained. On 1 September 1983, the Soviet Union shot down a Korean passenger airliner when it crossed into Soviet airspace—an act which Reagan characterized as a "massacre". The barbarity of this act, as the U.S. and indeed the world understood it, galvanized support for the deployment—which stood in place until the later accords between Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev.

The membership of the organization at this time remained largely static. In 1974, as a consequence of the Turkish invasion of Cyprus, Greece withdrew its forces from NATO's military command structure but, with Turkish cooperation, were readmitted in 1980. On 30 May 1982, NATO gained a new member when, following a referendum, the newly democratic Spain joined the alliance.

In November 1983, NATO manoeuvres simulating a nuclear launch caused panic in the Kremlin. The Soviet leadership, led by ailing General Secretary Yuri Andropov, became concerned that the manoeuvres, codenamed Able Archer 83, were the beginnings of a genuine first strike. In response, Soviet nuclear forces were readied and air units in East Germany and Poland were placed on alert. Though at the time written off by U.S. intelligence as a propaganda effort, many historians now believe that the Soviet fear of a NATO first strike was genuine.

Post Cold War

The end of the Cold War and the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact in 1991 removed the de facto main adversary of NATO. This caused a strategic re-evaluation of NATO's purpose, nature and tasks. In practice this ended up entailing a gradual (and still ongoing) expansion of NATO to Eastern Europe, as well as the extension of its activities to areas that had not formerly been NATO concerns. The first post-Cold War expansion of NATO came with German reunification on 3 October 1990, when the former East Germany became part of the Federal Republic of Germany and the alliance. This had been agreed in the Two Plus Four Treaty earlier in the year. To secure Soviet approval of a united Germany remaining in NATO, it was agreed that foreign troops and nuclear weapons would not be stationed in the east.

The scholar Stephen F. Cohen argued in 2005 that a commitment was given that NATO would never expand further east,[19] but according to Robert Zoellick, then a State Department official involved in the Two Plus Four negotiating process, this appears to be a misperception; no formal commitment of the sort was made.[20] On 7 May 2008, The Daily Telegraph held an interview with Gorbachev in which he repeated his view that such a commitment had been made. Gorbachev said "the Americans promised that NATO wouldn't move beyond the boundaries of Germany after the Cold War but now half of central and eastern Europe are members, so what happened to their promises? It shows they cannot be trusted."[21]

As part of post-Cold War restructuring, NATO's military structure was cut back and reorganized, with new forces such as the Headquarters Allied Command Europe Rapid Reaction Corps established. The Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe agreed between NATO and the Warsaw Pact and signed in Paris in 1990, mandated specific reductions. The changes brought about by the collapse of the Soviet Union on the military balance in Europe were recognized in the Adapted Conventional Armed Forces in Europe Treaty, signed some years later. France rejoined NATO's Military Committee in 1995, and since then has intensified working relations with the military structure. The policies of French President Nicolas Sarkozy have resulted in a major reform of France's military position, culminating with the return to full membership on 4 April 2009, which also included France rejoining the integrated military command of NATO, while maintaining an independent nuclear deterrent.[22]

Balkans interventions

The first NATO military operation caused by the conflict in the former Yugoslavia was Operation Sharp Guard, which ran from June 1993–October 1996. It provided maritime enforcement of the arms embargo and economic sanctions against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. On 28 February 1994, NATO took its first military action, shooting down four Bosnian Serb aircraft violating a U.N.-mandated no-fly zone over central Bosnia and Herzegovina. A NATO bombing campaign, Operation Deliberate Force, began in August, 1995, against the Army of the Republika Srpska, after the Srebrenica massacre. Operation Deny Flight, the no-fly-zone enforcement mission, had begun two years before, on 12 April 1993, and was to continue until 20 December 1995. NATO air strikes that year helped bring the war in Bosnia to an end, resulting in the Dayton Agreement, which in turn meant that NATO deployed a peacekeeping force, under Operation Joint Endeavor, first named IFOR and then SFOR, which ran from December 1996 to December 2004. Following the lead of its member nations, NATO began to award a service medal, the NATO Medal, for these operations.

Between 1994 and 1997, wider forums for regional cooperation between NATO and its neighbors were set up, like the Partnership for Peace, the Mediterranean Dialogue initiative and the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council. On 8 July 1997, three former communist countries, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Poland, were invited to join NATO, which finally happened in 1999. In 1998, the NATO-Russia Permanent Joint Council was established.

On 24 March 1999, NATO saw its first broad-scale military engagement in the Kosovo War, where it waged an 11-week bombing campaign, which NATO called Operation Allied Force, against what was then the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, in an effort to stop Serbian-led crackdown on Albanian civilians in Kosovo. A formal declaration of war never took place (in common with all wars since World War II). The conflict ended on 11 June 1999, when Yugoslavian leader Slobodan Milošević agreed to NATO’s demands by accepting UN resolution 1244. During the crisis, NATO also deployed one of its international reaction forces, the ACE Mobile Force (Land), to Albania as the Albania Force (AFOR), to deliver humanitarian aid to refugees from Kosovo.[23] NATO then helped establish the KFOR, a NATO-led force under a United Nations mandate that operated the military mission in Kosovo. In August–September 2001, the alliance also mounted Operation Essential Harvest, a mission disarming ethnic Albanian militias in the Republic of Macedonia.[24]

The United States, the United Kingdom, and most other NATO countries opposed efforts to require the U.N. Security Council to approve NATO military strikes, such as the action against Serbia in 1999, while France and some others claimed that the alliance needed U.N. approval. The U.S./U.K. side claimed that this would undermine the authority of the alliance, and they noted that Russia and China would have exercised their Security Council vetoes to block the strike on Yugoslavia, and could do the same in future conflicts where NATO intervention was required, thus nullifying the entire potency and purpose of the organization. Recognizing the post-Cold War military environment, NATO adopted the Alliance Strategic Concept during its Washington Summit in April 1999 that emphasized conflict prevention and crisis management.[25]

After the 11 September attacks

The 11 September attacks caused NATO to invoke Article 5 of the NATO Charter for the first time in its history. The Article says that an attack on any member shall be considered to be an attack on all. The invocation was confirmed on 4 October 2001 when NATO determined that the attacks were indeed eligible under the terms of the North Atlantic Treaty.[26] The eight official actions taken by NATO in response to the attacks included Operation Eagle Assist and Operation Active Endeavour. Operation Active Endeavour is a naval operation in the Mediterranean Sea and is designed to prevent the movement of terrorists or weapons of mass destruction as well as to enhance the security of shipping in general. It began on 4 October 2001.

Despite this early show of solidarity, NATO faced a crisis little more than a year later, when on 10 February 2003, France and Belgium vetoed the procedure of silent approval concerning the timing of protective measures for Turkey in case of a possible war with Iraq. Germany did not use its right to break the procedure but said it supported the veto.

On the issue of Afghanistan on the other hand, the alliance showed greater unity: on 16 April 2003, NATO agreed to take command of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan. The decision came at the request of Germany and the Netherlands, the two nations leading ISAF at the time of the agreement, and all nineteen NATO ambassadors approved it unanimously. The handover of control to NATO took place on 11 August, and marked the first time in NATO’s history that it took charge of a mission outside the north Atlantic area. Canada had originally been slated to take over ISAF by itself on that date.

In January 2004, NATO appointed Minister Hikmet Çetin, of Turkey, as the Senior Civilian Representative (SCR) in Afghanistan. Minister Cetin is primarily responsible for advancing the political-military aspects of the Alliance in Afghanistan. In August 2004, following U.S. pressure, NATO formed the NATO Training Mission - Iraq, a training mission to assist the Iraqi security forces in conjunction with the U.S. led MNF-I.[27]

On 31 July 2006, a NATO-led force, made up mostly of troops from Canada, the United Kingdom, Turkey and the Netherlands, took over military operations in the south of Afghanistan from a U.S.-led anti-terrorism coalition.

Expansion and restructuring

New NATO structures were also formed while old ones were abolished: The NATO Response Force (NRF) was launched at the 2002 Prague summit on 21 November. On 19 June 2003, a major restructuring of the NATO military commands began as the Headquarters of the Supreme Allied Commander, Atlantic were abolished and a new command, Allied Command Transformation (ACT), was established in Norfolk, Virginia, United States, and the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE) became the Headquarters of Allied Command Operations (ACO). ACT is responsible for driving transformation (future capabilities) in NATO, whilst ACO is responsible for current operations.

As a result of post-Cold War restructuring of national forces, intervention in the Balkan conflicts, and subsequent participation in Afghanistan, starting in late 2003 NATO has restructured how it commands and deploys its troops by creating several NATO Rapid Deployable Corps.

Membership went on expanding with the accession of seven more Northern European and Eastern European countries to NATO: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania and also Slovenia, Slovakia, Bulgaria, and Romania. They were first invited to start talks of membership during the 2002 Prague Summit, and joined NATO on 29 March 2004, shortly before the 2004 Istanbul summit. The same month, NATO's Baltic Air Policing began, which supported the sovereignty of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia by providing fighters to react to any unwanted aerial intrusions. Four fighters are based in Lithuania, provided in rotation by virtually all the NATO states. Operation Peaceful Summit temporarily enhanced this patrolling during the 2006 Riga summit.[28]

The 2006 Riga summit was held in Riga, Latvia, which had joined the Atlantic Alliance two years earlier. It is the first NATO summit to be held in a country that was part of the Soviet Union, and the second one in a former Comecon country (after the 2002 Prague summit). Energy Security was one of the main themes of the Riga Summit.[29] At the April 2008 summit in Bucharest, Romania, NATO agreed to the accession of Croatia and Albania and invited them to join. Both countries joined NATO in April 2009. Ukraine and Georgia were also told that they will eventually become members.[30]

International Security Assistance Force

In August 2003, NATO commenced its first mission ever outside Europe when it assumed control over International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan. However, some critics feel that national caveats or other restrictions undermine the efficiency of ISAF. For instance, political scientist Joseph Nye stated in a 2006 article that

"Many NATO countries with troops in Afghanistan have 'national caveats' that restrict how their troops may be used. While the Riga summit relaxed some of these caveats to allow assistance to allies in dire circumstances, Britain, Canada, the Netherlands, and the U.S. are doing most of the fighting in southern Afghanistan, while French, German, and Italian troops are deployed in the quieter north.It is difficult to see how NATO can succeed in stabilizing Afghanistan unless it is willing to commit more troops and give commanders more flexibility."[31]

Due to the intensity of the fighting in the south, France has recently allowed a squadron of Mirage 2000 fighter/attack aircraft to be moved into the area, to Kandahar, in order to reinforce the alliance's efforts.[32] If these caveats were to be eliminated, it is argued that this could help NATO to succeed. NATO is also training the ANA (Afghan National Army) to be better equipped in forcing out the Taliban.

NATO missile defence

For some years, the United States negotiated with Poland and the Czech Republic for the deployment of interceptor missiles and a radar tracking system in the two countries against wishes of local population [33] Both countries' governments indicated that they would allow the deployment. In August 2008, Poland and the United States signed a preliminary deal to place part of the missile defence shield in Poland that would be linked to air-defence radar in the Czech Republic.[34] In answer to this agreement, more than 130,000 Czechs signed a petition for a referendum on the base, which is by far the largest citizen initiative since the Velvet Revolution, but it has been refused.[35] The proposed American missile defence site in Central Europe is expected to be fully operational by 2015 and would be capable of covering most of Europe except parts of Romania plus Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey.[36]

In April 2007, NATO's European allies called for a NATO missile defence system which would complement the American national missile defense system to protect Europe from missile attacks and NATO's decision-making North Atlantic Council held consultations on missile defence in the first meeting on the topic at such a senior level.[36] In response, Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin claimed that such a deployment could lead to a new arms race and could enhance the likelihood of mutual destruction. He also suggested that his country would freeze its compliance with the 1990 Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE)—which limits military deployments across the continent—until all NATO countries had ratified the adapted CFE treaty.[37] Secretary General Jaap de Hoop Scheffer claimed the system would not affect strategic balance or threaten Russia, as the plan is to base only 10 interceptor missiles in Poland with an associated radar in the Czech Republic.[38]

On 14 July 2007, Russia gave notice of its intention to suspend the CFE treaty, effective 150 days later.[39][40] On 14 August 2008, the United States and Poland came to an agreement to place a base with 10 interceptor missiles with associated MIM-104 Patriot air defence systems in Poland. This came at a time when tension was high between Russia and most of NATO and resulted in a nuclear threat on Poland by Russia if the building of the missile defences went ahead. On 20 August 2008 the United States and Poland signed the agreement, with a statement from Russia saying their response "Will Go Beyond Diplomacy" and is an "extremely dangerous bundle" of military projects." Also, on 20 August 2008, Russia sent word to Norway that it was suspending ties with NATO.[41]

On 17 September 2009, US President Barack Obama announced that the planned deployment of long-range missile defence interceptors and equipment in Poland and the Czech Republic was not to go forward, and that a defence against short- and medium-range missiles using AEGIS warships would be deployed instead.[42] The announcement prompted varying reactions — in Central and Eastern Europe, especially in Poland and the Czech Republic, response was largely negative; while the Russian response was largely positive.[43] Following the announcement, Russian President Dimitri Medvedev announced that a planned Russian Iskander surface to surface missile deployment in nearby Kaliningrad was also not to go ahead. The two deployment cancellation announcements were later followed with a statement by newly named NATO Secretary General Anders Fogh Rasmussen calling for a strategic partnership between Russia and the Alliance, explicitly involving technological cooperation of the two parties' missile defence systems.[44]

Membership

| Members of NATO Membership Action Plan Intensified Dialogue | Individual Partnership Action Plan Partnership for Peace |

NATO has added new members seven times since first forming in 1949 (the last two in 2009). NATO comprises 28 members: Albania, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Future enlargement

New membership in the alliance has been largely from Eastern Europe and the Balkans, including former members of the Warsaw Pact. At the 2008 summit in Bucharest, three countries were promised future invitations: the Republic of Macedonia,[45] Georgia and Ukraine.[46] Though it has completed the requirements for membership, the accession of Macedonia is blocked by Greece, pending resolution of the Macedonia naming dispute.[47] Cyprus also has not progressed toward further relations, in part because of opposition from Turkey.[48]

Other potential candidate countries include Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina, which joined the Adriatic Charter of potential members in 2008.[49] Russia, as referred to above, continues to oppose further expansion, seeing it as inconsistent with understandings between Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev and U.S. President George H. W. Bush that allowed for a peaceful German reunification. NATO's expansion policy is seen by Moscow as a continuation of a Cold War attempt to surround and isolate Russia.[50]

Cooperation with non-member states

Euro-Atlantic Partnership

A double framework has been established to help further co-operation between the 28 NATO members and 22 "partner countries".

- The Partnership for Peace (PfP) program was established in 1994 and is based on individual bilateral relations between each partner country and NATO: each country may choose the extent of its participation. The PfP program is considered the operational wing of the Euro-Atlantic Partnership.[51] Members include all current and former members of the Commonwealth of Independent States.

- The Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council (EAPC) was first established on 29 May 1997, and is a forum for regular coordination, consultation and dialogue between all 49 participants.[52]

- The Mediterranean Dialogue was established in 1994 to coordinate in a similar way with Israel and countries in North Africa.

- The Istanbul Cooperation Initiative was announced in 2004 as a dialog forum for the Middle East along the same lines as the Mediterranean Dialogue. It has yet to be implemented.

- Other third countries also have been contacted for participation in some activities of the PfP framework such as Afghanistan.[53]

Individual Partnership Action Plans

Launched at the November 2002 Prague Summit, Individual Partnership Action Plans (IPAPs) are open to countries that have the political will and ability to deepen their relationship with NATO.[54]

Currently IPAPs are in implementation with the following countries:

Ukraine (22 November 2002)[55]

Ukraine (22 November 2002)[55] Georgia (29 October 2004)

Georgia (29 October 2004) Azerbaijan (27 May 2005)

Azerbaijan (27 May 2005) Armenia (16 December 2005)

Armenia (16 December 2005) Kazakhstan (31 January 2006)

Kazakhstan (31 January 2006) Moldova (19 May 2006)

Moldova (19 May 2006) Bosnia and Herzegovina (10 January 2008)

Bosnia and Herzegovina (10 January 2008) Montenegro (June 2008)

Montenegro (June 2008)

Contact Countries

Since 1990–91, the Alliance has gradually increased its contact with countries that do not form part of any of the above cooperative groupings. Political dialogue with Japan began in 1990, and a range of non-NATO countries have contributed to peacekeeping operations in the former Yugoslavia.

The Allies established a set of general guidelines on relations with other countries, beyond the above groupings in 1998.[56] The guidelines do not allow for a formal institutionalization of relations, but reflect the Allies’ desire to increase cooperation. Following extensive debate, the term Contact Countries was agreed by the Allies in 2004; the following countries currently have this status:

Structures

The main headquarters of NATO is located on Boulevard Léopold III, B-1110 Brussels, which is in Haren, part of the City of Brussels municipality.[57] A new headquarters building is, as of 2010[update], in construction nearby, due for completion in 2012. The current design is an adaptation of the original award-winning scheme designed by Larry Oltmanns and his team when he was a Design Partner with SOM.

The staff at the Headquarters is composed of national delegations of member countries and includes civilian and military liaison offices and officers or diplomatic missions and diplomats of partner countries, as well as the International Staff and International Military Staff filled from serving members of the armed forces of member states.[58] Non-governmental citizens' groups have also grown up in support of NATO, broadly under the banner of the Atlantic Council/Atlantic Treaty Association movement. Some maintain offices in or near the NATO headquarters building area.

NATO Parliamentary Assembly

The body that sets broad strategic goals for NATO is the NATO Parliamentary Assembly (NATO-PA) which meets at the Annual Session, and one other during the year, and is the organ that directly interacts with the parliamentary structures of the national governments of the member states which appoint Permanent Members, or ambassadors to NATO. The NATO Parliamentary Assembly, currently presided by John S. Tanner, a U.S. Representative (Democratic Party) from Tennessee, is made up of legislators from the member countries of the North Atlantic Alliance as well as thirteen associate members.[59] It is however officially a different structure from NATO, and has as aim to join together deputies of NATO countries in order to discuss security policies on the NATO Council.

The Assembly is the political integration body of NATO that generates political policy agenda setting for the NATO Council via reports of its five committees:

- Committee on the Civil Dimension of Security

- Defence and Security Committee

- Economics and Security Committee

- Political Committee

- Science and Technology Committee

These reports provide impetus and direction as agreed upon by the national governments of the member states through their own national political processes and influencers to the NATO administrative and executive organizational entities.

NATO Council

Like any alliance, NATO is ultimately governed by its 28 member states. However, the North Atlantic Treaty, and other agreements, outline how decisions are to be made within NATO. Each of the 28 members sends a delegation or mission to NATO's headquarters in Brussels, Belgium.[60] The senior permanent member of each delegation is known as the Permanent Representative and is generally a senior civil servant or an experienced ambassador (and holding that diplomatic rank). Several countries have diplomatic missions to NATO through embassies in Belgium.

Together, the Permanent Members form the North Atlantic Council (NAC), a body which meets together at least once a week and has effective governance authority and powers of decision in NATO. From time to time the Council also meets at higher level meetings involving Foreign ministers, Defence Ministers or Heads of State or Government (HOSG) and it is at these meetings that major decisions regarding NATO’s policies are generally taken. However, it is worth noting that the Council has the same authority and powers of decision-making, and its decisions have the same status and validity, at whatever level it meets. NATO summits also form a further venue for decisions on complex issues, such as enlargement.

The meetings of the North Atlantic Council are chaired by the Secretary General of NATO and, when decisions have to be made, action is agreed upon on the basis of unanimity and common accord. There is no voting or decision by majority. Each nation represented at the Council table or on any of its subordinate committees retains complete sovereignty and responsibility for its own decisions.

List of officials

| 1 | General Lord Ismay | 4 April 1952–16 May 1957 | |

| 2 | Paul-Henri Spaak | 16 May 1957–21 April 1961 | |

| 3 | Dirk Stikker | 21 April 1961–1 August 1964 | |

| 4 | Manlio Brosio | 1 August 1964–1 October 1971 | |

| 5 | Joseph Luns | 1 October 1971–25 June 1984 | |

| 6 | Lord Carrington | 25 June 1984–1 July 1988 | |

| 7 | Manfred Wörner | 1 July 1988–13 August 1994 | |

| 8 | Sergio Balanzino | 13 August 1994–17 October 1994 | |

| 9 | Willy Claes | 17 October 1994–20 October 1995 | |

| 10 | Sergio Balanzino | 20 October 1995–5 December 1995 | |

| 11 | Javier Solana | 5 December 1995–6 October 1999 | |

| 12 | Lord Robertson | 14 October 1999–17 December 2003 | |

| 13 | Alessandro Minuto-Rizzo | 17 December 2003–1 January 2004 | |

| 14 | Jaap de Hoop Scheffer | 1 January 2004–1 August 2009 | |

| 15 | Anders Fogh Rasmussen | 1 August 2009–present |

| # | Name | Country | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jonkheer van Vredenburch | 1952–1956 | |

| 2 | Baron Adolph Bentinck | 1956–1958 | |

| 3 | Alberico Casardi | 1958–1962 | |

| 4 | Guido Colonna di Paliano | 1962–1964 | |

| 5 | James A. Roberts | 1964–1968 | |

| 6 | Osman Olcay | 1969–1971 | |

| 7 | Paolo Pansa Cedronio | 1971–1978 | |

| 8 | Rinaldo Petrignani | 1978–1981 | |

| 9 | Eric da Rin | 1981–1985 | |

| 10 | Marcello Guidi | 1985–1989 | |

| 11 | Amedeo de Franchis | 1989–1994 | |

| 12 | Sergio Balanzino | 1994–2001 | |

| 13 | Alessandro Minuto Rizzo | 2001–2007 | |

| 14 | Claudio Bisogniero | 2007–2010 | |

| 15 | Hüseyin Diriöz | 2010–present |

Notes

- ↑ "The official Emblem of NATO". NATO. http://www.nato.int/multi/natologo.htm. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ↑ "English and French shall be the official languages for the entire North Atlantic Treaty Organization.", Final Communiqué following the meeting of the North Atlantic Council on 17 September 1949. "(..) the English and French texts [of the Treaty] are equally authentic (...)" The North Atlantic Treaty, Article 14

- ↑ Boulevard Leopold III-laan, B-1110 BRUSSELS, which is in Haren, part of the City of Brussels. "NATO homepage". http://www.nato.int/. Retrieved 7 March 2006.

- ↑ Reynolds, The origins of the Cold War in Europe. International perspectives, p.13

- ↑ Albania, Croatia join NATO military alliance, AFP, 1 April 2009

- ↑ Bram Boxhoorn, Broad Support for NATO in the Netherlands, 21 September 2005, ATAedu.org

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "The SIPRI Military Expenditure Database". Milexdata.sipri.org. http://milexdata.sipri.org/. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ "The 15 countries with the highest military expenditure in 2009". http://www.sipri.org/research/armaments/milex/resultoutput/15majorspenders. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ David C. Isby & Charles Kamps Jr, Armies of NATO's Central Front, Jane's Publishing Company Ltd 1985, p.13

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 With the accession of Greece and Turkey, this region was extended to an attack on: the Algerian Departments of France (which is not applicable anymore), on the territory of Turkey or on the islands under the jurisdiction of any of the Parties in the North Atlantic area north of the Tropic of Cancer. The validity was also extended to "vessels, forces or aircraft" of the parties, when north of the Tropic of Cancer. Protocol to the North Atlantic Treaty on the Accession of Greece and Turkey

- ↑ David C. Isby & Charles Kamps Jr, Armies of NATO's Central Front, Jane's Publishing Company Ltd 1985, p.13–14

- ↑ Robert E. Osgood, 'NATO: The Entangling Alliance,' University Press, Chicago, 1962, p.76, in William Park 'Defending the West,' Wheatsheaf Books, 1986, p.28

- ↑ Time magazine, The Man with the Oilcan, 24 March 1952

- ↑ Sean M. Maloney, 'To Secure Command of the Sea: NATO Command Organization and Naval Planning for the Cold War at Sea, 1945-54,' MA thesis, University of New Brunswick, 1991, p.270–291

- ↑ "Fast facts". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. http://www.cbc.ca/news/background/nato/.

- ↑ BBC On This Day "West Germany accepted into Nato" bbc.co.uk

- ↑ David C. Isby & Charles Kamps Jr, Armies of NATO's Central Front, Jane's Publishing Company Ltd 1985, p.15

- ↑ Washington Post, After 43 Years, France to Rejoin NATO as Full Member, March 2009

- ↑ Gorbachev's Lost Legacy by Stephen F. Cohen (link) The Nation, 24 February 2005

- ↑ Robert B. Zoellick, The Lessons of German Unification, The National Interest, 22 September 2000

- ↑ Gorbachev: US could start new Cold War Telegraph Retrieved on 22 May 2008

- ↑ Stratton, Allegra. "Sarkozy military plan unveiled". The Guardian, 17 June 2008

- ↑ NATO website describing AFOR

- ↑ NATO's role in FYROM

- ↑ "Allied Command Atlantic". NATO Handbook. NATO. http://www.nato.int/docu/handbook/2001/hb120704.htm. Retrieved 3 September 2008.

- ↑ "NATO Update: Invocation of Article 5 confirmed - 2 October 2001". Nato.int. http://www.nato.int/docu/update/2001/1001/e1002a.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ NATO Training Mission - Iraq, Introduction, 17 September 2007

- ↑ L. Neidinger "NATO team ensures safe sky during Riga Summit", 8 December 2006, AF.mil

- ↑ Nazemroaya, Mahdi Darius (17 May 2007). The Globalization of Military Power: NATO Expansion. Centre for Research on Globalization. http://www.globalresearch.ca/index.php?context=viewArticle&code=NAZ20070517&articleId=5677.

- ↑ U.S. wins NATO backing for missile defense shield - CNN.com

- ↑ J. Nye, "NATO after Riga", 14 December 2006, http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/nye40

- ↑ "La France et l'OTAN". LeMonde.fr. http://www.lemonde.fr/web/article/0,1-0@2-3232,36-949296@51-947771,0.html. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ Post Store. "U.S. Might Negotiate on Missile Defense". Washingtonpost.com. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/04/24/AR2007042400871.html. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ "CNN | Europe | Poland, U.S. sign missile shield deal". Edition.cnn.com. 2008-08-15. http://edition.cnn.com/2008/WORLD/europe/08/15/poland.us.shield/index.html. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ "Více jak 130 000 podpisů pro referendum". Nezakladnam.cz. 2008-08-27. http://www.nezakladnam.cz/cs/1228_vice-jak-130-000-podpisu-pro-referendum. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 "Xinhua - English". News.xinhuanet.com. 2007-04-19. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2007-04/19/content_6001014.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ "Europe | Russia in defence warning to US". BBC News. 2007-04-26. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/6594379.stm. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ "Europe | Nato chief dismisses Russia fears". BBC News. 2007-04-19. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/6570533.stm. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ BBC NEWS, "Russia suspends arms control pact", 14 July 2007

- ↑ Y. Zarakhovich, "Why Putin Pulled Out of a Key Treaty" in Time, 14 July 2007

- ↑ "MSNBC". MSNBC. 2008-08-20. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/26315674/. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ "News.BBC.co.uk". News.BBC.co.uk. 2009-09-17. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/8260230.stm. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ "News.BBC.co.uk". News.BBC.co.uk. 2009-09-18. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/8262050.stm. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ "News.BBC.co.uk". News.BBC.co.uk. 2009-09-18. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/8262515.stm. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ In NATO official statements, the country is always referred to as the "former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, with a footnote stating that "Turkey recognizes the Republic of Macedonia under its constitutional name"; see Macedonia naming dispute.

- ↑ George, J and J. M. Teigen (2008). "NATO Enlargement and Institution Building: Military Personnel Policy Challenges in the Post-Soviet Context", European Security 17(2), page 346 (DOI: 10.1080/09662830802642512).

- ↑ "Croatia & Albania Invited Into NATO". BalkanInsight. 3 April 2008. http://www.balkaninsight.com/en/main/news/9102/. Retrieved 3 April 2008.

- ↑ Simsek, Ayhan (June 14, 2007). "Cyprus a sticking point in EU-NATO co-operation". Southeast European Times. http://www.setimes.com/cocoon/setimes/xhtml/en_GB/features/setimes/features/2007/06/14/feature-03. Retrieved June 7, 2010.

- ↑ Ramadanovic, Jusuf; Nedjeljko Rudovic (12 September 2008). "Montenegro, BiH join Adriatic Charter". Southeast European Times. http://www.setimes.com/cocoon/setimes/xhtml/en_GB/features/setimes/features/2008/12/09/feature-02. Retrieved 24 March 2009.

- ↑ NATO Seeking to Weaken CIS by Expansion — Russian General (link) MosNews 01.12.2005 and Ukraine moves closer to NATO membership By Taras Kuzio, Jamestown Foundation and Global Realignment LRNA.org and Condoleezza Rice wants Russia to acknowledge United States's interests on post-Soviet space, Pravda 04 May 2006

- ↑ "NATO.int". NATO.int. http://www.nato.int/issues/pfp/index.html. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ "NATO Topics: The Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council". Nato.int. http://www.nato.int/issues/eapc/index.html. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ "Declaration by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan". Nato.int. http://www.nato.int/docu/basictxt/b060906e.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ "NATO Topics: Individual Partnership Action Plans". Nato.int. http://www.nato.int/issues/ipap/index.html. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ "NATO-Ukraine Action Plan". Nato.int. http://www.nato.int/docu/basictxt/b021122a.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ NATO, Relations with Contact Countries. Retrieved 18 June 2008.

- ↑ "NATO homepage". http://www.nato.int/. Retrieved 12 March 2006.

- ↑ "NATO Headquarters". Nato.int. 2010-08-10. http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/topics_49284.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ iBi Center (2010-02-12). "NATO PA - About the NATO Parliamentary Assembly". Nato-pa.int. http://www.nato-pa.int/Default.asp?SHORTCUT=1. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ "National delegations to NATO What is their role?". NATO. 18 June 2007. http://www.nato.int/issues/national_delegations/tasks.html. Retrieved 15 July 2007.

- ↑ "NATO Who's who? - Secretaries General of NATO". Nato.int. http://www.nato.int/cv/secgen.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ "NATO Who's who? - Deputy Secretaries General of NATO". Nato.int. http://www.nato.int/cv/depsecgen.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

References

- David C. Isby & Charles Kamps Jr, Armies of NATO's Central Front, Jane's Publishing Company Ltd 1985, ISBN 071060341X

Further reading

- Early period

- Francis A. Beer. Integration and Disintegration in NATO: Processes of Alliance Cohesion and Prospects for Atlantic Community. (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1969), 330 pp.

- Francis A. Beer. The Political Economy of Alliances: Benefits, Costs, and Institutions in NATO. (Beverly Hills: Sage, 1972), 40 pp.

- Eisenhower, Dwight D. The Papers of Dwight David Eisenhower. Vols. 12 and 13: NATO and the Campaign of 1952 : Louis Galambos et al., ed. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989. 1707 pp. in 2 vol.

- Gearson, John and Schake, Kori, ed. The Berlin Wall Crisis: Perspectives on Cold War Alliances Palgrave Macmillan, 2002. 209 pp.

- John C. Milloy. North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, 1948–1957: Community or Alliance? (2006), focus on non-military issues

- Smith, Joseph, ed. The Origins of NATO Exeter, UK University of Exeter Press, 1990. 173 pp.

- Late Cold War period

- Smith, Jean Edward, and Canby, Steven L.The Evolution of NATO with Four Plausible Threat Scenarios. Canada Department of Defence: Ottawa, 1987. 117 pp.

- Post Cold War period

- Asmus, Ronald D. Opening NATO's Door: How the Alliance Remade Itself for a New Era Columbia University Press, 2002. 372 pp.

- Bacevich, Andrew J. and Cohen, Eliot A. War over Kosovo: Politics and Strategy in a Global Age. Columbia University Press, 2002. 223 pp.

- Daclon, Corrado Maria Security through Science: Interview with Jean Fournet, Assistant Secretary General of NATO, Analisi Difesa, 2004. no. 42

- Gheciu, Alexandra. NATO in the 'New Europe' Stanford University Press, 2005. 345 pp.

- Hendrickson, Ryan C. Diplomacy and War at NATO: The Secretary General and Military Action After the Cold War University of Missouri Press, 2006. 175 pp.

- Lambeth, Benjamin S. NATO's Air War in Kosovo: A Strategic and Operational Assessment Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND, 2001. 250 pp.

- General histories

- Alasdair, Roberts (2002/2003). "NATO, Secrecy, and the Right to Information". East European Constitutional Review (New York University — School of Law) 11/12 (4/1): 86–94. http://www1.law.nyu.edu/eecr/vol11_12num4_1/special/roberts.pdf

- Kaplan, Lawrence S. The Long Entanglement: NATO's First Fifty Years. Praeger, 1999. 262 pp.

- Kaplan, Lawrence S. NATO Divided, NATO United: The Evolution of an Alliance. Praeger, 2004. 165 pp.

- Létourneau, Paul. Le Canada et l'OTAN après 40 ans, 1949–1989 Quebec: Cen. Québécois de Relations Int., 1992. 217 pp.

- Paquette, Laure. NATO and Eastern Europe After 2000 (New York: Nova Science, 2001).

- Powaski, Ronald E. The Entangling Alliance: The United States and European Security, 1950–1993. Greenwood Publishing Group, 1994. 261 pp.

- Telo, António José. Portugal e a NATO: O Reencontro da Tradiçoa Atlântica Lisbon: Cosmos, 1996. 374 pp.

- Sandler, Todd and Hartley, Keith. The Political Economy of NATO: Past, Present, and into the 21st Century. Cambridge Uiversity Press, 1999. 292 pp.

- Zorgbibe, Charles. Histoire de l'OTAN Brussels: Complexe, 2002. 283 pp.

- Other issues

- Kaplan, Lawrence S., ed. American Historians and the Atlantic Alliance. Kent State University Press, 1991. 192 pp.

External links

| Wikinews has news related to:

NATO

|

- NATO including Basic NATO Documents

- Andrew J. Pierre, NATO at Fifty: New Challenges, Future Uncertainties U.S. Institute of Peace, 22 March 1999, link verified February 2009

- Bridget Kendall, NATO searches for defining role BBC, February 2005

- Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, One for all: The North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (extracts, 1947–2003, link verified February 2009)

- Fundación para el análisis y los estudios sociales (Spain), NATO: an Alliance for Freedom, 2005

- United States Air Force Air War College, Congressional Research Service (CRS) Reports regarding NATO, link verified February 2009

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||