Muslim world

The term Muslim world (or Islamic world) has several meanings. In a cultural sense, it refers to the worldwide community of Muslims, adherents of Islam. This community numbers about 1.57 billion people, roughly one-fifth of the world population. This community is spread across many different nations and ethnic groups connected by religion and a shared sense of humanity. In a historical or geopolitical sense, the term usually refers collectively to Muslim majority countries or countries in which Islam dominates politically.

The worldwide Muslim community is also known collectively as the ummah. Islam emphasizes unity and defense of fellow Muslims, although many divisions of Islam (see Sunni-Shia relations, for example) exist. In the past both Pan-Islamism and nationalist currents have influenced the status of the Muslim world.

Current reports from various sources have estimated that 1.2 to 1.57 billion Muslims populate the world, or about 25% of an estimated 2010 world population of 6.8 billion[1] with 80% in Asia (20% in the Middle East ) and 20% of Muslims living in North Africa.[2][3][4][5] Muslims in non-Asian countries account for a minority of total Muslim populations and they are mostly of Asian origin; from South Asia, Central Asia and Middle-east.

More than half of the Muslim population of the world including those from Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, Indonesia and some from Central Asia(Afghanistan) are descendants of local (Hindu, Buddhist & animist) converts. Almost all of them were converted (spanning over a millenium) by heavy preaching and services and not by force.[6], [7] Most of the Muslim population in these regions is of local origin with undetectable or minor to obvious levels of gene flow from outside, primarily from Iran and Central Asia, rather than directly from the Arabian Peninsula.[8], [9]

Contents |

History

Muslim history involves the history of the Islamic faith as a religion and as a social institution. The history of Islam began in Arabia with the Islamic prophet Muhammad's first recitations of the Qur'an in the 7th century. Under the Rashidun and Umayyads, the Caliphate grew rapidly geographically expansion of Muslim power well beyond the Arabian peninsula in the form of a vast Muslim Empire with an area of influence that stretched from northwest India, across Central Asia, the Middle East, North Africa, southern Italy, and the Iberian Peninsula, to the Pyrenees.

During much of the 20th century, the Islamic identity and the dominance of Islam on political issues have arguably increased during the early 21st century. The fast-growing Western interests in Islamic regions, international conflicts and globalization have changed the influence of Islam on the world in contemporary history.[10]

Classical culture

| This article is part of the series: |

|

| Islam |

| Beliefs |

| Allah · Oneness of God Prophets · Revealed books Angels |

| Practices |

| Profession of faith · Prayer Fasting · Charity · Pilgrimage |

| Texts and laws |

| Qur'an · Sunnah · Hadith Fiqh · Sharia · Kalam · Sufism |

| History and leadership |

| Timeline · Spread of Islam Ahl al-Bayt · Sahaba Sunni · Shi'a · Others Rashidun · Caliphate Imamate |

| Culture and society |

| Academics · Animals · Art Calendar · Children Demographics · Festivals Mosques · Philosophy Science · Women Politics · Dawah |

| Islam and other religions |

| Christianity · Judaism Hinduism · Sikhism · Jainism · Mormonism |

| See also |

| Criticism Glossary of Islamic terms |

| Islam portal |

The Islamic Golden Age, also sometimes known as the Islamic Renaissance,[11] is traditionally dated from the 7th to 13th centuries C.E.,[12] but has been extended to the 15th and 16th[13] centuries by more recent scholarship.

Arts

The term "Islamic art and architecture" denotes the works of art and architecture produced from the 7th century onwards by people who lived within the territory that was inhabited by culturally Islamic populations.[14][15]

Aniconism and Arabesque

No Islamic visual images or depictions of God are meant to exist because it is believed that such artistic depictions may lead to idolatry. Moreover, Muslims believe that God is incorporeal, making any two- or three- dimensional depictions impossible. Instead, Muslims describe God by the names and attributes that, according to Islam, he revealed to his creation. All but one sura of the Qur'an begins with the phrase "In the name of God, the Beneficent, the Merciful". Images of Mohammed are likewise prohibited. Such aniconism and iconoclasm[16] can also be found in Jewish and some Christian theology.

Islamic art frequently adopts the use of geometrical floral or vegetal designs in a repetition known as arabesque. Such designs are highly nonrepresentational, as Islam forbids representational depictions as found in pre-Islamic pagan religions. Despite this, there is a presence of depictional art in some Muslim societies, notably the miniature style made famous in Persia and under the Ottoman Empire which featured not only paintings of people and animals but also depictions of Qur'anic stories and Islamic traditional narratives. Another reason why Islamic art is usually abstract is to symbolize the transcendence, indivisible and infinite nature of God, an objective achieved by arabesque.[17] Arabic calligraphy is an omnipresent decoration in Islamic art, and is usually expressed in the form of Qur'anic verses. Two of the main scripts involved are the symbolic kufic and naskh scripts, which can be found adorning the walls and domes of mosques, the sides of minbars, and so on.[17]

Distinguishing motifs of Islamic architecture have always been ordered repetition, radiating structures, and rhythmic, metric patterns. In this respect, fractal geometry has been a key utility, especially for mosques and palaces. Other significant features employed as motifs include columns, piers and arches, organized and interwoven with alternating sequences of niches and colonnettes.[18] The role of domes in Islamic architecture has been considerable. Its usage spans centuries, first appearing in 691 with the construction of the Dome of the Rock mosque, and recurring even up until the 17th century with the Taj Mahal. And as late as the 19th century, Islamic domes had been incorporated into Western architecture.[19][20]

Ceramics

From between the eighth and eighteenth centuries, the use of glazed ceramics was prevalent in Islamic art, usually assuming the form of elaborate pottery.[21] Tin-opacified glazing was one of the earliest new technologies developed by the Islamic potters. The first Islamic opaque glazes can be found as blue-painted ware in Basra, dating to around the 8th century. Another significant contribution was the development of stonepaste ceramics, originating from 9th century Iraq.[22] Other centers for innovative ceramic pottery in the Odd world included Fustat (from 975 to 1075), Damascus (from 1100 to around 1600) and Tabriz (from 1470 to 1550).[23]

Architecture

Perhaps the most important expression of Islamic art is architecture, particularly that of the mosque.[24] Through it the effect of varying cultures within Islamic civilization can be illustrated. The North African and Iberian Islamic architecture, for example, has Roman-Byzantine elements, as seen in the Alhambra palace at Granada, or in the Great Mosque of Cordoba. Persian-style mosques are characterized by their tapered brick pillars, large arcades, and arches supported each by several pillars. In South Asia, elements of Hindu architecture were employed, but were later superseded by Persian designs. The most numerous and largest of mosques exist in Turkey, which obtained influence from Byzantine, Persian and Syrian designs, although Turkish architects managed to implement their own style of cupola domes.[24]

Literature

The best known work of fiction from the Islamic world is The Book of One Thousand and One Nights or (Arabian Nights), which is a compilation of folk tales. The original concept is derived from a pre-Islamic Persian prototype that probably relied partly on Indian elements[25]. It reached its final form by the 14th century; the number and type of tales have varied from one manuscript to another.[26] All Arabian fantasy tales tend to be called "Arabian Nights" stories when translated into English, regardless of whether they appear in The Book of One Thousand and One Nights or not.[26] This work has been very influential in the West since it was translated in the 18th century, first by Antoine Galland.[27] Many imitations were written, especially in France.[28] Various characters from this epic have themselves become cultural icons in Western culture, such as Aladdin, Sinbad and Ali Baba.

A famous example of Arabic poetry and Persian poetry on romance (love) is Layla and Majnun, dating back to the Umayyad era in the 7th century. It is a tragic story of undying love much like the later Romeo and Juliet, which was itself said to have been inspired by a Latin version of Layli and Majnun to an extent.[29] Ferdowsi's Shahnameh, the national epic of Iran, is a mythical and heroic retelling of Persian history. Amir Arsalan was also a popular mythical Persian story, which has influenced some modern works of fantasy fiction, such as The Heroic Legend of Arslan.

Ibn Tufail (Abubacer) and Ibn al-Nafis were pioneers of the philosophical novel. Ibn Tufail wrote the first Arabic novel Hayy ibn Yaqdhan (Philosophus Autodidactus) as a response to al-Ghazali's The Incoherence of the Philosophers, and then Ibn al-Nafis also wrote a novel Theologus Autodidactus as a response to Ibn Tufail's Philosophus Autodidactus. Both of these narratives had protagonists (Hayy in Philosophus Autodidactus and Kamil in Theologus Autodidactus) who were autodidactic feral children living in seclusion on a desert island, both being the earliest examples of a desert island story. However, while Hayy lives alone with animals on the desert island for the rest of the story in Philosophus Autodidactus, the story of Kamil extends beyond the desert island setting in Theologus Autodidactus, developing into the earliest known coming of age plot and eventually becoming the first example of a science fiction novel.[30][31]

Theologus Autodidactus, written by the Arabian polymath Ibn al-Nafis (1213–1288), is the first example of a science fiction novel. It deals with various science fiction elements such as spontaneous generation, futurology, the end of the world and doomsday, resurrection, and the afterlife. Rather than giving supernatural or mythological explanations for these events, Ibn al-Nafis attempted to explain these plot elements using the scientific knowledge of biology, astronomy, cosmology and geology known in his time. His main purpose behind this science fiction work was to explain Islamic religious teachings in terms of science and philosophy through the use of fiction.[32]

A Latin translation of Ibn Tufail's work, Philosophus Autodidactus, first appeared in 1671, prepared by Edward Pococke the Younger, followed by an English translation by Simon Ockley in 1708, as well as German and Dutch translations. These translations later inspired Daniel Defoe to write Robinson Crusoe, regarded as the first novel in English.[33][34][35][36] Philosophus Autodidactus also inspired Robert Boyle to write his own philosophical novel set on an island, The Aspiring Naturalist.[37] The story also anticipated Rousseau's Emile: or, On Education in some ways, and is also similar to Mowgli's story in Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle Book as well as Tarzan's story, in that a baby is abandoned but taken care of and fed by a mother wolf.[38]

Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy, considered the greatest epic of Italian literature, derived many features of and episodes about the hereafter directly or indirectly from Arabic works on Islamic eschatology: the Hadith and the Kitab al-Miraj (translated into Latin in 1264 or shortly before[39] as Liber Scale Machometi, "The Book of Muhammad's Ladder") concerning Muhammad's ascension to Heaven, and the spiritual writings of Ibn Arabi. The Moors also had a noticeable influence on the works of George Peele and William Shakespeare. Some of their works featured Moorish characters, such as Peele's The Battle of Alcazar and Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice, Titus Andronicus and Othello, which featured a Moorish Othello as its title character. These works are said to have been inspired by several Moorish delegations from Morocco to Elizabethan England at the beginning of the 17th century.[40]

Philosophy

One of the common definitions for "Islamic philosophy" is "the style of philosophy produced within the framework of Islamic culture."[41] Islamic philosophy, in this definition is neither necessarily concerned with religious issues, nor is exclusively produced by Muslims.[41] The Persian scholar Ibn Sina (Avicenna) (980-1037) had more than 450 books attributed to him. His writings were concerned with many subjects, most notably philosophy and medicine. His medical textbook The Canon of Medicine was used as the standard text in European universities for centuries. His works on Aristotle was a key step in the transmission of learning from ancient Greeks to the Islamic world and the West. He often corrected the philosopher, encouraging a lively debate in the spirit of ijtihad. He also wrote The Book of Healing, an influential scientific and philosophical encyclopedia. His thinking and that of his follower Ibn Rushd (Averroes) was incorporated into Christian philosophy during the Middle Ages, notably by Thomas Aquinas.

One of the most influential Muslim philosophers in the West was Averroes (Ibn Rushd), founder of the Averroism school of philosophy, whose works and commentaries had an impact on the rise of secular thought in Western Europe.[42] He also developed the concept of "existence precedes essence".[43] Avicenna also founded his own Avicennism school of philosophy, which was influential in both Islamic and Christian lands. He was also a critic of Aristotelian logic and founder of Avicennian logic, and he developed the concepts of empiricism and tabula rasa, and distinguished between essence and existence.

Another influential philosopher who had a significant influence on modern philosophy was Ibn Tufail. His philosophical novel, Hayy ibn Yaqdhan, translated into Latin as Philosophus Autodidactus in 1671, developed the themes of empiricism, tabula rasa, nature versus nurture,[44] condition of possibility, materialism,[45] and Molyneux's Problem.[46] European scholars and writers influenced by this novel include John Locke,[47] Gottfried Leibniz,[36] Melchisédech Thévenot, John Wallis, Christiaan Huygens,[48] George Keith, Robert Barclay, the Quakers,[49] and Samuel Hartlib.[37]

Islamic philosophers continued making advances in philosophy through to the 17th century, when Mulla Sadra founded his school of Transcendent Theosophy and developed the concept of existentialism.[50]

Other influential Muslim philosophers include al-Jahiz, a pioneer in evolutionary thought; Ibn al-Haytham (Alhacen), a pioneer of phenomenology and the philosophy of science and a critic of Aristotelian natural philosophy and Aristotle's concept of place (topos); Biruni, a critic of Aristotelian natural philosophy; Ibn Tufail and Ibn al-Nafis, pioneers of the philosophical novel; Shahab al-Din Suhrawardi, founder of Illuminationist philosophy; Fakhr al-Din al-Razi, a critic of Aristotelian logic and a pioneer of inductive logic; and Ibn Khaldun, a pioneer in the philosophy of history[51] and social philosophy.

Sciences

Muslim scientists made significant advances in the sciences. They placed far greater emphasis on experiment than had the Greeks. This led to an early scientific method being developed in the Muslim world, where significant progress in methodology was made, beginning with the experiments of Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) on optics from circa 1000, in his Book of Optics. The most important development of the scientific method was the use of experiments to distinguish between competing scientific theories set within a generally empirical orientation, which began among Muslim scientists. Ibn al-Haytham is also regarded as the father of optics, especially for his empirical proof of the intromission theory of light. Some have also described Ibn al-Haytham as the "first scientist" for his development of the modern scientific method.[52][53][54]

The mathematician Al-Khwarizmi, from whose name the word algorithm derives, is considered to be the father of algebra (which is named after his book, kitab al-jabr).[55] Recent studies show that it is very likely that the Medieval Muslim artists were aware of advanced decagonal quasicrystal geometry (discovered half a millennium later in 1970s and 1980s in West) and used it in intricate decorative tilework in the architecture.[56] Muslim mathematicians also made several refinements to the Arabic numerals , such as the introduction of decimal point notation.

Muslim physicians contributed significantly to the field of medicine, including the subjects of anatomy and physiology: such as in the 15th century Persian work by Mansur ibn Muhammad ibn al-Faqih Ilyas entitled Tashrih al-badan (Anatomy of the body) which contained comprehensive diagrams of the body's structural, nervous and circulatory systems; or in the work of the Egyptian physician Ibn al-Nafis, who proposed the theory of pulmonary circulation. Avicenna's The Canon of Medicine remained an authoritative medical textbook in Europe until the 18th century. Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi (also known as Abulcasis) contributed to the discipline of medical surgery with his Kitab al-Tasrif ("Book of Concessions"), a medical encyclopedia which was later translated to Latin and used in European and Muslim medical schools for centuries. Other medical advancements came in the fields of pharmacology and pharmacy.[57]

In astronomy, al-Battani improved the precision of the measurement of the precession of the Earth's axis. The corrections made to the geocentric model by al-Battani, Averroes, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, Mo'ayyeduddin Urdi and Ibn al-Shatir were later incorporated into the Copernican heliocentric model. Heliocentric theories were also discussed by several other Muslim astronomers such as Abu-Rayhan Biruni, Al-Sijzi, Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi, and Najm al-Dīn al-Qazwīnī al-Kātibī. The astrolabe, though originally developed by the Greeks, was perfected by Islamic astronomers and engineers, and was subsequently brought to Europe.

Muslim chemists and alchemists played an important role in the foundation of modern chemistry. Scholars such as Will Durant and Alexander von Humboldt regard Muslim chemists to be the founders of chemistry. In particular, Jābir ibn Hayyān is regarded as the "father of chemistry". The works of Arab chemists influenced Roger Bacon (who introduced the empirical method to Europe, strongly influenced by his reading of Arabic writers), and later Isaac Newton. A number of chemical processes (particularly in alchemy) and distillation techniques (such as the production of alcohol) were developed in the Muslim world and then spread to Europe.

Some of the most famous scientists from the Islamic world include Jābir ibn Hayyān (polymath, father of chemistry), al-Farabi (polymath), Abu al-Qasim (father of modern surgery),[58] Ibn al-Haytham (universal genius, father of optics, founder of psychophysics and experimental psychology,[59] pioneer of scientific method, "first scientist"), Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī (universal genius, father of Indology[60] and geodesy, "first anthropologist"),[61] Avicenna (universal genius, father of momentum[62] and modern medicine),[63] Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī (polymath), and Ibn Khaldun (father of demography,[64] cultural history,[65] historiography,[66] the philosophy of history, sociology,[51] and the social sciences),[67] among many others.

Technology

In technology, the Muslim world adopted papermaking from China.[68] The knowledge of gunpowder was also transmitted from China via Islamic countries, where the formulas for pure potassium nitrate and an explosive gunpowder effect were first developed.[69][70]

Advances were made in irrigation and farming, using new technology such as the windmill. Crops such as almonds and citrus fruit were brought to Europe through al-Andalus, and sugar cultivation was gradually adopted by the Europeans. Arab merchants dominated trade in the Indian Ocean until the arrival of the Portuguese in the 16th century. Hormuz was an important center for this trade. There was also a dense network of trade routes in the Mediterranean, along which Muslim countries traded with each other and with European powers such as Venice, Genoa and Catalonia. The Silk Road crossing Central Asia passed through Muslim states between China and Europe.

Muslim engineers in the Islamic world made a number of innovative industrial uses of hydropower, and early industrial uses of tidal power, wind power, steam power,[71] fossil fuels such as petroleum, and early large factory complexes (tiraz in Arabic).[72] The industrial uses of watermills in the Islamic world date back to the 7th century, while horizontal-wheeled and vertical-wheeled water mills were both in widespread use since at least the 9th century. A variety of industrial mills were being employed in the Islamic world, including early fulling mills, gristmills, hullers, sawmills, shipmills, stamp mills, steel mills, sugar mills, tide mills and windmills. By the 11th century, every province throughout the Islamic world had these industrial mills in operation, from al-Andalus and North Africa to the Middle East and Central Asia.[68] Muslim engineers also invented crankshafts and water turbines, employed gears in mills and water-raising machines, and pioneered the use of dams as a source of water power, used to provide additional power to watermills and water-raising machines.[73] Such advances made it possible for many industrial tasks that were previously driven by manual labour in ancient times to be mechanized and driven by machinery instead in the medieval Islamic world. The transfer of these technologies to medieval Europe had an influence on the Industrial Revolution.[74]

A number of industries were active during the Arab Agricultural Revolution, producing goods including astronomical instruments, ceramics, chemicals, clocks, glass, matting, pulp and paper, perfume, petroleum, pharmaceuticals, rope, silk, sugar, textiles, and weapons. Also important to the economy of the period were the use of mechanical hydropower and wind power, shipbuilding, and the mining of minerals such as sulfur, lead and iron. Early factories (tiraz) were built for many of these industries, and knowledge of these industries was later transmitted to medieval Europe, especially during the Latin translations of the 12th century. For example, the first glass factories in Europe were founded in the 11th century by Egyptian craftsmen in Greece.[75] The agricultural and handicraft industries also experienced high levels of growth during this period.[76]

Modern world

Economy and trade

In circa 1800, the gross domestic product of the Muslim world was estimated at about 12 per cent of the world total. By the end of the 19th century, this share had plunged to about 5 per cent of the world total. This share then stagnated throughout the 20th century.

As of 2008, the Arab World accounts for two-fifth of the gross domestic product and three-fifth of the trade of the wider Muslim World. Oil industry and related services account for almost two-fifth of the gross domestic product of the Muslim world.

Indonesia, Saudi Arabia and Turkey are members of the G-20 major economies.

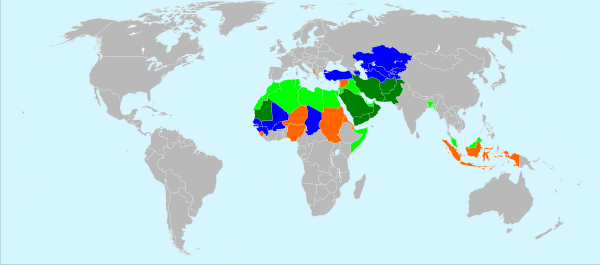

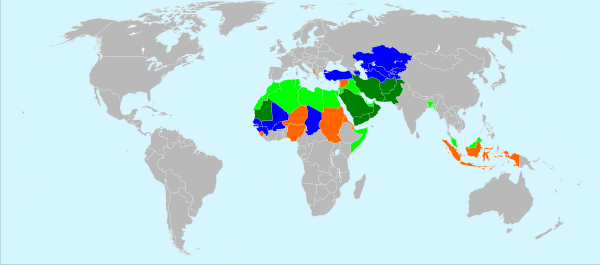

Geographic spread

Many Muslims not only live in, but also have an official status in the following regions:

- Southwest Asia: Arab nations such as Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Oman, United Arab Emirates, Kuwait and non-Arab nations such as Iran.

- Africa: North African countries such as Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt; Northeast African countries like Somalia, Somaliland (de facto state), Eritrea, Ethiopia, Djibouti and Sudan; and West African countries like Mali, Senegal, Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Burkina Faso, Sierra Leone, Niger and Nigeria.

- Southern Europe: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Northern Cyprus and Turkey.

- Eastern Europe: Azerbaijan, parts of Russia (North Caucasus and Idel-Ural) and Ukraine (especially in the Crimea)

- Central Asia: Afghanistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan

- South Asia: Pakistan, Bangladesh, and the Maldives

- East Asia: parts of China (Xinjiang, Ningxia and Qinghai)

- Southeast Asia: Indonesia, Brunei and Malaysia

The countries of Southwest Asia, and many in Northern and Northeastern Africa are considered part of the Greater Middle East.

In Chechnya, Dagestan, Kabardino-Balkaria, Karachay-Cherkessia, Ingushetia, Tatarstan, Bashkiria in Russia, Muslims are in the majority.

Some definitions would also include the sizable Muslim minorities in:

- several countries of Europe (Of which the Muslim population in Cyprus, Russia, Montenegro, Bulgaria, France, the Netherlands and Denmark make up at least 5% of the total population of that country, and with more than 37 million Muslims, collectively, living in Russia, France, Germany, United Kingdom, Netherlands,[77] and Italy)

- several regions of Russia, other than ethnic republics above (Adyghea, North Ossetia etc.)

- some parts of India (India has the third-largest population of Muslims of any country; see: Islam in India)

- Singapore, Myanmar, Pattani (Thailand), and Mindanao (Philippines)

- Guyana, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago.

- Democratic Republic of Congo, Burundi, Malawi, South Africa, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Uganda, Ethiopia

- Crimea in Ukraine

Demographics

One fifth of the world population share Islam as an ethical tradition. Estimates conclude that the number of Muslims in the world ranges between 1.3 to 1.8 billion, with the most accepted figure being around 1.6 billion. Muslims are the majority in 57 countries, they speak about 60 languages and come from diverse ethnic backgrounds. Arabic is the most spoken language of Muslims, and is spoken by 20% of Muslims. Bengali is the second most commonly spoken language, spoken by around 14% of the total population, and Punjabi is the third most spoken language (spoken by around 5% of Muslim world). But if Urdu/Hindi or Hindusthani is included, both of which are same except in script; then it is probably the most spoken Islamic language with more than 270 millions Muslims compared to 210 millions Muslims for Bengali and 246 millions for Arabic. Bahasa Indonesia is also a major language group of the Muslim world spoken by 165 millions Muslim. Other major languages spoken by the Muslims are Javanese, Turkish and Persian. In conclusion, almost all of the Muslims speak some form of language which is a mixture of Sanskrit and Arabic borne languages.

Important organizations

|

|

The Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC) is an inter-governmental organization grouping fifty-seven States. These States decided to pool their resources together, combine their efforts and speak with one voice to safeguard the interest and ensure the progress and well-being of their peoples and those of other Muslims in the world over.

The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries includes many nations that are also in the Arab League.

A politically motivated oil embargo in 1974 (to support Egypt and Syria in the 1973 Yom Kippur War against Israel after the US re-equipped Israel with armaments) had drastic economic and political consequences in the United States and Europe.

Religion and state

Islamic law does not distinguish between "matters of church" and "matters of state"; the ulema function as both jurists and theologians. In practice, Islamic rulers frequently bypassed the Sharia courts with a parallel system of so-called "Grievance courts" over which they had sole control.

As the Muslim world came into contact with Western secular ideals, Muslim societies responded in different ways. Turkey has been governed as a secular state ever since the reforms of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. In contrast, the 1979 Iranian Revolution replaced a mostly secular regime with an Islamic republic led by the Ayatollah Ruholla Khomeini.[78] The Republic of Turkey is the first democratic and secular republic in the Muslim world.

Many Muslim countries still have a strong belief in the religion of Islam, many have used Sharia law in the state where the law runs from the interpretations from the Quran and the Hadith in the society of politics, law, schools and others. Most countries in the Muslim world according to their constitution declare Islam as the state religion or Sharia law, but a very few who are Secular states compared with the western world.

Countries

Countries in the Muslim world sorted by state religion:

Islamic states

Islamic State have adopted Islam as the ideological foundation for their political institution.

State religion

State Religion are religious body or creed officially endorsed by the state.

Secular states

Secular State are officially neutral in matters of religion, neither supporting nor opposing any particular religions.

Law and ethics

In some nations, Muslim ethnic groups enjoy considerable autonomy.

In some places, Muslims implement a form of Islamic law, called shariah in Arabic. The Islamic law exists in many variations, but the main forms are the five (four Sunni and one Shia) schools of jurisprudence (fiqh):

- Hanafi school in Pakistan,India, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Turkey, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Egypt, Spain, Morocco, Canada, Maldives, Iraq and West Africa

- Maliki in North Africa and West Africa

- Shafi'i in Malaysia, Qatar, Indonesia, Egypt, Eritrea, Somalia and Yemen

- Hanbali in Arabia, Qatar

- Jaferi in Iran, Iraq, Bahrain and Azerbaijan. These four are the only "muslim states" where the majority is Shia and in Yemen, India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Lebanon where the Shia are numerically significant.

Some Muslim women often dress modestly to show off their high characters. Thus, in some countries, the Islamic law requires women to cover either just legs, shoulders and head or the whole body apart from the face. In strictest forms, the face as well must be covered leaving just a mesh to see through. These rules for dressing cause tension between the Western World and the Muslim, concerning particularly Muslims living in western countries, since many in the Western World consider these restrictions both sexist and oppressive. Most Muslims oppose this charge, and instead declare that the media-fuelled world of the West is itself sexist and oppressive in that women are forced to reveal irrational amounts of flesh to be considered attractive.

Islamic economics bans interest or Riba (Usury) but in most Muslim countries Western banking is allowed.

Islam in modern politics and conflicts

Many people in Islamic countries also see Islam manifested politically as Islamism. Political Islam is powerful in all Muslim-majority countries. Islamic parties in Turkey, Pakistan and Algeria have taken power at the provincial level. Many in these movements call themselves Islamists, which also sometimes describes more militant Islamic groups. The relationships between these groups (in democratic countries there is usually at least one Islamic party) and their views of democracy are complex.

Some of these groups are accused of practicing Islamist terrorism.

Conflicts with Israel

Israel is subject to varying levels of hostility in the Muslim world due to the creation of the state of Israel in Palestine, known to Jews as the Land of Israel, which is sacred for both Jews and Muslims, and due to the prolonged Arab-Israeli conflict and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Turkey was the first Muslim-majority state to recognize Israel, just one year after its founding, and they have the longest shared close military and economic ties. Prior to the Iranian Revolution, Iran and Israel maintained a strong political friendship, however the current Iranian government is strongly anti-Israeli and has repeatedly called for Israel's destruction. Once at war, both Egypt and Jordan have established diplomatic relations and signed peace treaties with Israel, and attempts to resolve the conflict with Palestinians have produced a number of interim agreements. Nine non-Arab Muslim states maintain diplomatic ties with Israel, and since 1994, the Persian Gulf states have lessened their enforcement of the Arab boycott, with Saudi Arabia even declaring its end in 2005, though it has yet to cancel its sanctions. States like Morocco that have large Jewish populations have generally had less hostile relations with Israel.

Nuclear capabilities

Pakistan is the only declared nuclear nation in the Muslim World. The nuclear program of Pakistan was carried out in response to India's nuclear test in 1974. Pakistan conducted its nuclear tests in May 1998.

See also: Gulf War

See also: Nuclear program of Iran

Recent history

1979 was a critical year in the Muslim world's relationship with the rest of the world. In that year, Egypt made peace with Israel, the monarchy of Iran was overthrown in the Iranian Revolution, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan began.

Some of the events pivotal in the Muslim world's relationship with the outside world in the post-Soviet era were:

- The Iran–Iraq War

- The 1991 Persian Gulf War

- The Bosnian War

- The Kosovo War

- The 1982-2000 South Lebanon conflict

- The Kargil War

- The 2001 invasion of Afghanistan

- The 2003 invasion of Iraq

- The Syrian occupation of Lebanon

- The 2005 Prophet Muhammad cartoons controversy

- The Second Sudanese Civil War

- The 2006 Israel-Lebanon conflict

- The 2006 controversy over remarks quoted by Pope Benedict XVI

- The 2007 Lebanon conflict

- The ongoing Darfur conflict

- The ongoing standoff with Iran over its Nuclear program

- The ongoing Second Chechen War

- The ongoing Waziristan War

- The ongoing Islamic Insurgency in the Philippines

- The ongoing war in Somalia

- The 2008 Kosovo declaration of independence

The U.S.-led War on Terrorism has been criticized as a War on Islam by Hizb ut-Tahrir and other Islamist organizations.

In 2009, in his first formal television interview as U.S. President, Barack Obama addressed the Muslim world through an Arabic-language satellite TV network Al-Arabiya. He called for a new partnership, "based on mutual respect and mutual interest." The American envoy to the region is former Sen. George J. Mitchell.

Political currents

- In Pakistan, a prominent U.S. ally, Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal - an Islamic political party - won local elections in two out of four of the country's provinces and became in mid-2003 the third largest party in the national parliament, their strongest showing up to that point. They had support from urban areas for the first time. See also: Politics of Pakistan

- In Kuwait elections in July 2003 returned Islamic traditionalists and supporters of the royal family, while liberals suffered a severe defeat. See also: Elections in Kuwait

- In Iran in 1979, a popular revolution saw the exile of the Shah and the rule going to Ayatollah Khomeini, a cleric from the Shia school of thought. The country has what it claims is a theocratic democracy, and has kept the "revolution" as part of the state's survival and growth.

- In 2008, Kosovo declared independence from Serbia.

- In Turkey, political Islam has taken a more moderate tack, driven by a strongly secular military; the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, or AK Party) has been in government since the elections of 2002.

Major denominations

The two main denominations of Islam are the Sunni and Shia sects. They differ primarily upon of how the life of the ummah ("faithful") should be governed, and the role of the imam. These two main differences stem from the understanding of which hadith are to interpret the Quran. The Shia minority believes that the Family of the Prophet's traditions are exclusively to be followed, whereas the Sunni majority believes in traditions from the Companions of the Prophet and other common people to be followed.

The overwhelming majority of Muslims in the world, approximately 85%, are Sunni.

Shias and other (Ibadiyyas-ismailis) make up the rest, about 15% of overall Muslim population. Among the countries with Shi'a majority or substantial population are Iran (80%), Azerbaijan (85%), Iraq (60%–65%), Bahrain (60%), Kuwait (40%), Pakistan (25-33%), India 25-31% of Muslim Population and (3-4%) of entire Population of India and Lebanon (35-40%).

The Kharijite Muslims, who are less known, have their own stronghold in the country of Oman holding about 75% of the population. The rest of the population being 15% Shia and the rest Sunni.

See also

- General

- Shia–Sunni relations, Ummah, caliphate, Hajj, Islam and other religions, Islam and secularism,

- Islamic

- Pan-Islamism, Islamic republic, Divisions of the world in Islam, Islam by country

- Muslim

- Muslim majority countries, Muslim history

- Arab

- Arab world, Arab nationalism, Pan-Arabism

- Islamic philosophy

- Islamic philosophy, Early Islamic philosophy, Contemporary Islamic philosophy, Liberal movements within Islam

- Christianity

- Christendom, Caesaropapism, Church militant and church triumphant, Ecumene, Res publica christiana

- Other

- Western world, Organization of the Islamic Conference

Geographical distribution

Schools of law |

Schools of law |

Muslim states |

Muslim officiality |

Percentage of muslims |

Percentage of muslims |

Notes

- ↑ PBS - Islam Today (Islam, followed by more than a billion people today, is the world's fastest growing religion and will soon be the world's largest. The 1.2 billion Muslims make up approximately one quarter of the world's population, and the Muslim population of the United States now outnumbers that of Episcopalians...)

- ↑ "Mapping the Global Muslim Population". PewForum.org The report, by the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, took three years to compile, with census data from 232 countries and terrotories. http://pewforum.org/docs/?DocID=450. Retrieved 2009-11-08.

- ↑ Tom Kington (2008-03-31). "Number of Muslims ahead of Catholics, says Vatican". The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2008/mar/31/religion. Retrieved 2008-11-17.

- ↑ "Muslim Population". IslamicPopulation.com. http://www.islamicpopulation.com/. Retrieved 2008-11-17.

- ↑ "Field Listing - Religions". https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2122.html. Retrieved 2008-11-17.

- ↑ Islam in South and Southeast Asia, CRS Report for Congress, Bruce Vaughn, Analyst in Southeast and South Asian Affairs, Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade

- ↑ [http://www.islamproject.org/education/B04_SpreadofIslam.htm

- ↑ http://www.nature.com/jhg/journal/v54/n6/full/jhg200938a.html

- ↑ Islam in South Asia

- ↑ http://www.islamonline.net/servlet/Satellite?c=Article_C&cid=1212925100226&pagename=Zone-English-ArtCulture%2FACELayout Milestones of Islamic History

- ↑ Joel L. Kraemer (1992), Humanism in the Renaissance of Islam, p. 1 & 148, Brill Publishers, ISBN 90-04-07259-4.

- ↑ Matthew E. Falagas, Effie A. Zarkadoulia, George Samonis (2006). "Arab science in the golden age (750–1258 C.E.) and today", The FASEB Journal 20, p. 1581-1586.

- ↑ Ahmad Y Hassan, Factors Behind the Decline of Islamic Science After the Sixteenth Century

- ↑ Ettinghausen (2003), p.3

- ↑ "Islamic Art and Architecture", The Columbia Encyclopedia (2000)

- ↑ "Muslim Iconoclasm". Encyclopedia of the Orient. http://lexicorient.com/e.o/mus_iconoclasm.htm. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Madden (1975), pp.423-430

- ↑ Tonna (1990), pp.182-197

- ↑ Grabar, O. (2006) p.87

- ↑ Ettinghausen (2003), p.87

- ↑ Mason (1995) p.1

- ↑ Mason (1995) p.5

- ↑ Mason (1995) p.7

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 "Islam", The New Encyclopedia Britannica (2005)

- ↑ Marzolph (2007). "Arabian Nights". Encyclopaedia of Islam. I. Leiden: Brill.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Arabian fantasy", p 51 ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ↑ L. Sprague de Camp, Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers: The Makers of Heroic Fantasy, p 10 ISBN 0-87054-076-9

- ↑ John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Arabian fantasy", p 52 ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ↑ NIZAMI: LAYLA AND MAJNUN - English Version by Paul Smith

- ↑ Dr. Abu Shadi Al-Roubi (1982), "Ibn Al-Nafis as a philosopher", Symposium on Ibn al-Nafis, Second International Conference on Islamic Medicine: Islamic Medical Organization, Kuwait (cf. Ibn al-Nafis As a Philosopher, Encyclopedia of Islamic World).

- ↑ Nahyan A. G. Fancy (2006), "Pulmonary Transit and Bodily Resurrection: The Interaction of Medicine, Philosophy and Religion in the Works of Ibn al-Nafīs (d. 1288)", p. 95-101, Electronic Theses and Dissertations, University of Notre Dame.

- ↑ Dr. Abu Shadi Al-Roubi (1982), "Ibn Al-Nafis as a philosopher", Symposium on Ibn al Nafis, Second International Conference on Islamic Medicine: Islamic Medical Organization, Kuwait (cf. Ibnul-Nafees As a Philosopher, Encyclopedia of Islamic World).

- ↑ Nawal Muhammad Hassan (1980), Hayy bin Yaqzan and Robinson Crusoe: A study of an early Arabic impact on English literature, Al-Rashid House for Publication.

- ↑ Cyril Glasse (2001), New Encyclopedia of Islam, p. 202, Rowman Altamira, ISBN 0-7591-0190-6.

- ↑ Amber Haque (2004), "Psychology from Islamic Perspective: Contributions of Early Muslim Scholars and Challenges to Contemporary Muslim Psychologists", Journal of Religion and Health 43 (4): 357-377 [369].

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Martin Wainwright, Desert island scripts, The Guardian, 22 March 2003.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 G. J. Toomer (1996), Eastern Wisedome and Learning: The Study of Arabic in Seventeenth-Century England, p. 222, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-820291-1.

- ↑ Latinized Names of Muslim Scholars, FSTC.

- ↑ I. Heullant-Donat and M.-A. Polo de Beaulieu, "Histoire d'une traduction," in Le Livre de l'échelle de Mahomet, Latin edition and French translation by Gisèle Besson and Michèle Brossard-Dandré, Collection Lettres Gothiques, Le Livre de Poche, 1991, p. 22 with note 37.

- ↑ Professor Nabil Matar (April 2004), Shakespeare and the Elizabethan Stage Moor, Sam Wanamaker Fellowship Lecture, Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre (cf. Mayor of London (2006), Muslims in London, pp. 14-15, Greater London Authority)

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 "Islamic Philosophy", Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy (1998)

- ↑ Majid Fakhry (2001). Averroes: His Life, Works and Influence. Oneworld Publications. ISBN 1-85168-269-4.

- ↑ Irwin, Jones (Autumn 2002). "Averroes' Reason: A Medieval Tale of Christianity and Islam". The Philosopher LXXXX (2).

- ↑ G. A. Russell (1994), The 'Arabick' Interest of the Natural Philosophers in Seventeenth-Century England, pp. 224-262, Brill Publishers, ISBN 90-04-09459-8.

- ↑ Dominique Urvoy, "The Rationality of Everyday Life: The Andalusian Tradition? (Aropos of Hayy's First Experiences)", in Lawrence I. Conrad (1996), The World of Ibn Tufayl: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Ḥayy Ibn Yaqẓān, pp. 38-46, Brill Publishers, ISBN 90-04-09300-1.

- ↑ Muhammad ibn Abd al-Malik Ibn Tufayl and Léon Gauthier (1981), Risalat Hayy ibn Yaqzan, p. 5, Editions de la Méditerranée.

- ↑ G. A. Russell (1994), The 'Arabick' Interest of the Natural Philosophers in Seventeenth-Century England, pp. 224-239, Brill Publishers, ISBN 90-04-09459-8.

- ↑ G. A. Russell (1994), The 'Arabick' Interest of the Natural Philosophers in Seventeenth-Century England, p. 227, Brill Publishers, ISBN 90-04-09459-8.

- ↑ G. A. Russell (1994), The 'Arabick' Interest of the Natural Philosophers in Seventeenth-Century England, p. 247, Brill Publishers, ISBN 90-04-09459-8.

- ↑ Kamal, Muhammad (2006). Mulla Sadra's Transcendent Philosophy. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.. pp. 9 & 39. ISBN 0754652718. OCLC 238761259 61169850 224496901 238761259 61169850.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Dr. S. W. Akhtar (1997). "The Islamic Concept of Knowledge", Al-Tawhid: A Quarterly Journal of Islamic Thought & Culture 12 (3).

- ↑ Bradley Steffens (2006), Ibn al-Haytham: First Scientist, Morgan Reynolds Publishing, ISBN 1-59935-024-6.

- ↑ Gorini, Rosanna (October 2003). "Al-Haytham the man of experience. First steps in the science of vision" (pdf). Journal of the International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine 2 (4): 53–55. http://www.ishim.net/ishimj/4/10.pdf. Retrieved 2008-09-25. "According to the majority of the historians al-Haytham was the pioneer of the modern scientific method. With his book he changed the meaning of the term optics and established experiments as the norm of proof in the field. His investigations are based not on abstract theories, but on experimental evidences and his experiments were systematic and repeatable.".

- ↑ Robert Briffault (1928), The Making of Humanity, p. 190-202, G. Allen & Unwin Ltd:

“ "What we call science arose as a result of new methods of experiment, observation, and measurement, which were introduced into Europe by the Arabs. [...] Science is the most momentous contribution of Arab civilization to the modern world, but its fruits were slow in ripening. [...] The debt of our science to that of the Arabs does not consist in startling discoveries or revolutionary theories; science owes a great deal more to Arab culture, it owes its existence....The ancient world was, as we saw, pre-scientific. [...] The Greeks systematized, generalized and theorized, but the patient ways of investigations, the accumulation of positive knowledge, the minute methods of science, detailed and prolonged observation and experimental inquiry were altogether alien to the Greek temperament." ” - ↑ Ron Eglash(1999), p.61

- ↑ Peter J. Lu, Harvard's Office of News and Public Affairs

- ↑ Turner, H. (1997) pp. 136—138

- ↑ A. Martin-Araguz, C. Bustamante-Martinez, Ajo V. Fernandez-Armayor, J. M. Moreno-Martinez (2002). "Neuroscience in al-Andalus and its influence on medieval scholastic medicine", Revista de neurología 34 (9), p. 877-892.

- ↑ Omar Khaleefa (Summer 1999). "Who Is the Founder of Psychophysics and Experimental Psychology?", American Journal of Islamic Social Sciences 16 (2).

- ↑ Zafarul-Islam Khan, At The Threshhold Of A New Millennium – II, The Milli Gazette.

- ↑ Akbar S. Ahmed (1984). "Al-Beruni: The First Anthropologist", RAIN 60, p. 9-10.

- ↑ Seyyed Hossein Nasr, "Islamic Conception Of Intellectual Life", in Philip P. Wiener (ed.), Dictionary of the History of Ideas, Vol. 2, p. 65, Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, 1973-1974.

- ↑ Cas Lek Cesk (1980). "The father of medicine, Avicenna, in our science and culture: Abu Ali ibn Sina (980-1037)", Becka J. 119 (1), p. 17-23.

- ↑ H. Mowlana (2001). "Information in the Arab World", Cooperation South Journal 1.

- ↑ Mohamad Abdalla (Summer 2007). "Ibn Khaldun on the Fate of Islamic Science after the 11th Century", Islam & Science 5 (1), p. 61-70.

- ↑ Salahuddin Ahmed (1999). A Dictionary of Muslim Names. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 1-85065-356-9.

- ↑ Akbar Ahmed (2002). "Ibn Khaldun’s Understanding of Civilizations and the Dilemmas of Islam and the West Today", Middle East Journal 56 (1), p. 25.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Adam Robert Lucas (2005), "Industrial Milling in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds: A Survey of the Evidence for an Industrial Revolution in Medieval Europe", Technology and Culture 46 (1), p. 1-30 [10].

- ↑ Ahmad Y Hassan, Potassium Nitrate in Arabic and Latin Sources, History of Science and Technology in Islam.

- ↑ Ahmad Y Hassan, Gunpowder Composition for Rockets and Cannon in Arabic Military Treatises In Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries, History of Science and Technology in Islam.

- ↑ Ahmad Y Hassan (1976). Taqi al-Din and Arabic Mechanical Engineering, p. 34-35. Institute for the History of Arabic Science, University of Aleppo.

- ↑ Maya Shatzmiller, p. 36.

- ↑ Ahmad Y Hassan, Transfer Of Islamic Technology To The West, Part II: Transmission Of Islamic Engineering

- ↑ Adam Robert Lucas (2005), "Industrial Milling in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds: A Survey of the Evidence for an Industrial Revolution in Medieval Europe", Technology and Culture 46 (1), p. 1-30.

- ↑ Ahmad Y Hassan, Transfer Of Islamic Technology To The West, Part 1: Avenues Of Technology Transfer

- ↑ Subhi Y. Labib (1969), "Capitalism in Medieval Islam", The Journal of Economic History 29 (1), p. 79-96.

- ↑ Centraal Bureau van de Statistiek (CBS) - Netherlands/ Muslimpopulation

- ↑ See:

- Esposito (2004), p.84

- Lapidus (2002), pp.502–507,845

- Lewis (2003), p.100

- ↑ Article 1 Islamic republic, Article 2 Religions

- ↑ Article 1 Sovereignty, Constitutional Monarchy

- ↑ Article 2The Islamic republic

- ↑ Article 1 State Integrity, Equal Protection (1)

- ↑ Article 2 Religion

- ↑ Article 1 (1)Introductory

- ↑ Article (1), (2), (3) The foundations of the state

- ↑ Article 2 Chapter I Algeria

- ↑ Article 2A The state religion

- ↑ Article 2The state

- ↑ Article 2, 1st Basic principles

- ↑ Article 2 The state and the system government

- ↑ Article 2 State religion, language

- ↑ Article 3 (1)

- ↑ State religion (7.) State, sovereignty and citizens

- ↑ Article 6 Basic principles

- ↑ Article 1

- ↑ Susan M. Hassig, Zawiah Abdul Latif, Somalia, (Marshall Cavendish: 2007), p.77.

- ↑ [1] Sidebar, "Country Profile; Religion section"

- ↑ Article 1 (State) General Provisions

- ↑ Democratic regime in an Islamic and Arab society

- ↑ Article 31

- ↑ Article 1 (1)

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 Article 1

- ↑ Article 25

- ↑ Article 1

- ↑ CIAWorld Factbook- Djibouti

- ↑ Article 1 (1)

- ↑ Characteristics of the Republic: Article 2, Provisions Relating to Political Parties: Article 68, Oath taking: Article 81, Oath: Article 103, Department of Religious Affairs: 136, Preservation of Reform Laws: 174

- ↑ Article 1 (1)

- ↑ Article 1

- ↑ Section 1: Foundations of the constitutional order, Article 1

- ↑ Article 7/Article 18

References

- Ankerl, Guy (2000) [2000]. Global communication without universal civilization. INU societal research. Vol.1: Coexisting contemporary civilizations : Arabo-Muslim, Bharati, Chinese, and Western. Geneva: INU Press. ISBN 2-88155-004-5. OCLC 237431578 47105537 50042854 223231547 237431578 47105537 50042854.

- Graham, Mark, How Islam Created the Modern World (2006)

- Tausch, Arno (2009). What 1.3 Billion Muslims Really Think: An Answer to a Recent Gallup Study, Based on the “World Values Survey”. Foreword Mansoor Moaddel, Eastern Michigan University (1st ed.). Nova Science Publishers, New York. ISBN 978-1-60692-731-1.

External links

- The Islamic World to 1600 an online tutorial at the University of Calgary, Canada.

- Qantara.de-Dossier: Democracy and Civil Society in Muslim countries

- Is There a Muslim World?, on NPR

- (English) Asabiyya: Re-Interpreting Value Change in Globalized Societies

- (English) Why Europe has to offer a better deal towards its Muslim communities. A quantitative analysis of open international data

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||