Mirtazapine

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

| (±)-1,2,3,4,10,14b-hexahydro-2-[11C]methylpyrazino(2,1-a)pyrido(2,3-c)(2)benzazepine | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 61337-67-5 |

| ATC code | N06AX11 |

| PubChem | CID 4205 |

| DrugBank | DB00370 |

| ChemSpider | 4060 |

| Chemical data | |

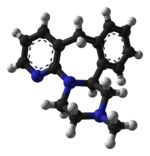

| Formula | C17H19N3 |

| Mol. mass | 265.35 g/mol |

| SMILES | eMolecules & PubChem |

| Synonyms | 6-Azamianserin, Org 3770 |

| Physical data | |

| Melt. point | 114–116 °C (237–241 °F) |

| Solubility in water | Soluble in methanol and chloroform mg/mL (20 °C) |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 50% |

| Metabolism | Liver (enzymes CYP2D6 and CYP3A4)[1] |

| Half-life | 20-40 hours |

| Excretion | Urine (75%), Feces (15%) |

| Therapeutic considerations | |

| Pregnancy cat. | C |

| Legal status | ℞ Prescription only |

| Routes | Oral |

Mirtazapine (Remeron, Avanza, Zispin, Reflex) is a tetracyclic antidepressant (TeCA) used primarily in the treatment of depression. It is also sometimes used as a hypnotic, antiemetic, and appetite stimulant, and for the treatment of anxiety, among other indications. Along with its close analogues mianserin and setiptiline, mirtazapine is one of the few noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (NaSSAs).

Esmirtazapine, the (S)-(+)-enantiomer of mirtazapine, is currently under development for the treatment of insomnia and menopausal symptoms by the same company that produced mirtazapine.[2]

Contents |

History

Mirtazapine was introduced by Organon International in the United States in 1990 for the treatment of depression. It quickly spread throughout the world and became a widely used antidepressant.

Indications

Clinical

Mirtazapine's primary use is the treatment of major depressive disorder.[3] Mirtazapine has been found to be useful in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder,[4][5] social anxiety disorder,[6][7][8][9][10] obsessive-compulsive disorder,[11][12][13] panic disorder,[14][15][16][17][18] post-traumatic stress disorder,[19][20][21][22][23][24] seasonal affective disorder,[25] insomnia,[26][27][28] nausea and vomiting,[27][29][30][31][32][33][34] diminished appetite and associated weight loss,[33][35][36], and itching[37][38][39][40] as well, and it may be prescribed off-label for these conditions.

Experimental

Mirtazapine has had literature published on its efficacy (or lack thereof) in the following areas: for the treatment of sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome,[41][42][43][44][45] headaches such as migraines,[46][47] tension headaches,[48][49][50] post-dural puncture headaches[51] and cluster headaches,[52] hyperemesis gravidarum,[53][54][55] irritable bowel syndrome,[56][57] gastroparesis,[58] dysgeusia, undifferentiated somatoform disorder,[59] autism and other pervasive developmental disorders,[60][61][62][63][64] and neuroleptic-induced akathisia.[65][66][66][67][68][69][70]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Mirtazapine is an antagonist/inverse agonist at the following receptors:[71][72]

|

As well as an inhibitor of the following transporters:

- Norepinephrine transporter (Ki = 4,600 nM)

All affinities listed were assayed using human materials except those for α1-adrenergic and mACh which are for rat tissues, due to human values being unavailable.[71][72] Though not known to have ever been screened, mirtazapine may act on the 5-HT6 and α2B-adrenergic receptors as well. Notably, mianserin (which is 6-desazamirtazapine) has been shown to have high affinity for 5-HT6 and does not produce cAMP accumulation (indicating it is an antagonist).[75]

Antagonization of the α2-adrenergic receptors which function largely as autoreceptors and heteroreceptors enhances adrenergic and serotonergic neurotransmission, notably central 5-HT1A receptor-mediated transmission in the dorsal raphe nucleus and hippocampus.[3][76][77][78][79] Because of this, mirtazapine has been said to be a functional "indirect agonist" of the 5-HT1A receptor.[78] Increased activation of the central 5-HT1A receptor is thought to be a major mediator of efficacy of most antidepressant drugs.[80] Unlike most conventional antidepressants, however, mirtazapine is not a reuptake inhibitor and has no appreciable affinity for the serotonin, norepinephrine, or dopamine transporters, nor is it an MAOI or have any efficacy at inhibiting/inducing any other enzyme for that matter.

More recent findings suggest that mirtazapine also possesses a second antidepressant property, which is likely to be just as important as its actions at the α2-adrenergic receptor in mitigating depression, mirtazapine's secondary antidepressant properties are likely to be mediated by its blockade of serotonin receptors, notably 5-HT2C.[81][82][83][83] The 5-HT2C receptor normally works to inhibit the release of the neurotransmitters dopamine and norepinephrine in various parts of the brain, notably in the pleasure centers such as the ventral tegmental area (VTA).[84][85] By blocking it, mirtazapine disinhibits dopamine and norepinephrine activity in these areas, causing a pronounced antidepressant and anxiolytic response.[86] Indeed, the novel antidepressant agomelatine acts primarily as a 5-HT2C receptor antagonist and has antidepressant efficacy at least comparable to that of the SSRIs and SNRIs.[87][88]

Antagonism of the 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors has beneficial effects on anxiety, sleep and appetite, as well as sexual function regarding the latter receptor.[76][89] Additionally, antagonism of the 5-HT3 receptor, the mechanism of action of antiemetic ondansetron, significantly improves pre-existing symptoms of nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and general irritable bowel syndrome in afflicted individuals.[90] Mirtazapine may be used as an inexpensive antiemetic alternative to ondansetron.[30] Blockade of the 5-HT3 receptors has also shown to improve anxiety and to be effective in the treatment of drug addiction in several studies.[91] Mirtazapine appears to enhance memory function as well and reverses scopolamine-induced memory deficits in rodents,[92] effects which may be attributed to 5-HT3 antagonism.[93] In contrast to mirtazapine, the SSRIs, SNRIs, TCAs, and MAOIs all increase the general activity of the 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, and 5-HT3 receptors, leading to a host of negative changes and side effects, the most prominent of which include anorexia, insomnia, sexual dysfunction (impaired libido and anorgasmia), nausea, and diarrhea, among others. As a result, mirtazapine is often used in conjunction with these drugs to reduce their side effect profile and to produce a stronger antidepressant effect.[89][94][95][96][97][98]

Mirtazapine is a very strong H1 receptor antagonist and as a result, it can cause powerful sedative and hypnotic effects.[83] After a short period of chronic treatment, however, the H1 receptor tends to sensitize and the antihistamine effects become more tolerable. Many patients may also dose at night to avoid the effects and this appears to be an effective strategy for combating them. Blockade of the H1 receptor may improve pre-existing allergies, pruritus, nausea, and insomnia in afflicted individuals; hence, this may actually be a positive thing for some. It may also contribute to weight gain, however. Mirtazapine has very low affinity for the muscarinic acetylcholine receptors and therefore lacks significant anticholinergic properties at clinically used doses.

Pharmacokinetics

Mirtazapine is typically prescribed in doses ranging from 15 mg to 45 mg. However, in severely depressed individuals, doses as high as 120 mg have been used with success. Mirtazapine has a half-life of approximately 20–40 hours. Like most other antidepressants, because of the "therapeutic lag" mirtazapine may require as long as 2–4 weeks until the therapeutic benefits of the drug become evident.

Chemistry

Mirtazapine is a racemic mixture of enantiomers and the (S)-(+)-enantiomer is known as esmirtazapine.

A four step chemical synthesis of mirtazapine has been published.[99][100]

Efficacy and tolerability

Mirtazapine has been found to be one of the most effective antidepressants available and has a generally tolerable side effect profile. In a major systematic review published in 2009 which compared the efficacy and tolerability of 12 popular antidepressants, mirtazapine was found to be superior to all of the included SSRIs and SNRIs, reboxetine, bupropion, and mianserin in terms of antidepressant efficacy, while it was average in regards to tolerability.[76][101][102] Mirtazapine has been demonstrated to be superior to trazodone as well.[103] Mirtazapine has also been shown to be equal in efficacy to many of the TCAs, including amitriptyline, doxepin, and clomipramine, but with a much improved tolerability profile.[76][89] However, two other studies found mirtazapine inferior to the TCA imipramine.[104][105] One study compared the combination of venlafaxine and mirtazapine versus the MAOI tranylcypromine and found them to be equally effective, though the MAOI was much less tolerable in terms of side effects and drug interactions.[94]

Side effects

Common side effects of mirtazapine: dizziness, blurred vision, sedation, somnolence, malaise/lassitude, increased appetite and subsequent weight gain,[106], dry mouth, constipation, enhanced libido and sexual function, and vivid, bizarre, lucid dreams or nightmares.

Rarer side effects: agitation/restlessness, irritability, aggression, apathy and/or anhedonia (emotional blunting), excessive mellowness or calmness, difficulty swallowing, shallow breathing, decreased body temperature, miosis, nocturnal emissions, spontaneous orgasm, loss of balance, and restless legs syndrome.[76][107][108][109] Mirtazapine has also occasionally been reported to cause mild hallucinogenic effects in some patients, including mental imagery, auditory and visual hallucinations. Most of these side effects are generally mild and become less prominent over time.[76]

Very rare, potentially serious adverse reactions may include allergic reaction, edema, fainting, seizures, bone marrow suppression, myelodysplasia[109], and agranulocytosis (occurs in 1/1,000 patients).

Mirtazapine has a lower risk to cause many of the side effects encountered with other antidepressants, such as decreased appetite, insomnia, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, urinary retention, increased body temperature, increased perspiration/sweating, mydriasis, and sexual dysfunction (consisting of loss of libido and anorgasmia).[76][89]

In general, some antidepressants may have the capacity to exacerbate some patients' depression or anxiety or cause suicidal ideation, particularly early in the treatment. It has been proven that mirtazapine has a faster onset of antidepressant action compared to SSRIs.[110]

Discontinuation

Mirtazapine and other antidepressants may cause a withdrawal upon discontinuation.[76][111][112][113] It should be noted that withdrawal effects from psychoactive drugs such as antidepressants are not uncommon; but are typically less severe than seen with benzodiazepines.[114] A gradual and slow reduction in dose is recommended in order to minimize withdrawal symptoms.[115] Effects of sudden cessation of treatment with mirtazapine may include depression, anxiety, panic attacks, vertigo, restlessness, irritability, decreased appetite, insomnia, diarrhea, nausea and vomiting, flu-like symptoms such as allergies and pruritus, headache, and sometimes hypomania/mania.[111][112][116][117][118]

Interactions

The potential for dangerous drug interactions with mirtazapine is considered to be very low, if not completely negligible. As a serotonin receptor antagonist, mirtazapine will not cause serotonin syndrome at any dose, nor is it capable of causing tyramine-induced hypertensive crisis, unlike the SSRIs and MAOIs, respectively. In fact, mirtazapine can actually be used to treat serotonin syndrome.[119]

Mirtazapine may, however, increase the effects of warfarin and sedative drugs, such as alcohol, benzodiazepines, and barbiturates, and it has also been reported to reduce or block the effects of some street drugs including hallucinogens such as MDMA, LSD and magic mushrooms. Carbamazepine and phenytoin decrease effects of mirtazapine. Cimetidine, azole-antifungals, HIV protease inhibitors, erythromycin and nefazodone may increase effects of mirtazapine.

Mirtazapine in combination with an SSRI, SNRI, or TCA as an augmentation strategy is safe and is often used therapeutically.[89][94][95][96][98] Mirtazapine and MAOIs are said to be contraindicated by some sources; however, there is no true indication that this is actually the case, and there is no proper literature on the subject warning against the combination whatsoever. Only a single study has mentioned anything significantly important regarding the combination, and they reported that it does not result in any incidence of serotonin-related toxicity.[120] However, mirtazapine has been associated with inducing hypertension in clonidine-treated patients.[121]

Overdose

Mirtazapine is relatively safe if an overdose is taken.[122] Unlike the TCAs, mirtazapine shows no significant cardiovascular adverse effects at 7 to 22 times the maximum recommended dose.[89] Overdose with as much as 30 to 50 times the standard dose has shown to be relatively non-toxic.[123] One case in which 1,200 mg was ingested proved non-fatal.[124]

12 fatalities have been attributed to mirtazapine overdose in literature.[125][126] However, the fatal toxicity index (FTI: deaths per million prescriptions) for mirtazapine is only 3.1 (95% CI: 0.1 to 17.2). This is similar to that observed with SSRIs.[127]

See also

|

|

References

- ↑ Timmer CJ, Sitsen JM, Delbressine LP (June 2000). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of mirtazapine". Clinical Pharmacokinetics 38 (6): 461–74. doi:10.2165/00003088-200038060-00001. PMID 10885584. http://content.wkhealth.com/linkback/openurl?issn=0312-5963&volume=38&issue=6&spage=461.

- ↑ "Future Treatments for Depression, Anxiety, Sleep Disorders, Psychosis, and ADHD -- Neurotransmitter.net". http://www.neurotransmitter.net/newdrugs.html.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Gorman JM (1999). "Mirtazapine: clinical overview". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60 Suppl 17: 9–13; discussion 46–8. PMID 10446735.

- ↑ Gambi F, De Berardis D, Campanella D, et al. (September 2005). "Mirtazapine treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a fixed dose, open label study". Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England) 19 (5): 483–7. doi:10.1177/0269881105056527. PMID 16166185.

- ↑ Goodnick PJ, Puig A, DeVane CL, Freund BV (July 1999). "Mirtazapine in major depression with comorbid generalized anxiety disorder". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60 (7): 446–8. PMID 10453798.

- ↑ Van Veen JF, Van Vliet IM, Westenberg HG (November 2002). "Mirtazapine in social anxiety disorder: a pilot study". International Clinical Psychopharmacology 17 (6): 315–7. doi:10.1097/00004850-200211000-00008. PMID 12409686. http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=0268-1315&volume=17&issue=6&spage=315.

- ↑ Muehlbacher M, Nickel MK, Nickel C, et al. (December 2005). "Mirtazapine treatment of social phobia in women: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 25 (6): 580–3. PMID 16282842. http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=0271-0749&volume=25&issue=6&spage=580.

- ↑ Mörtberg E (August 2006). "Mirtazapine reduces social anxiety and improves quality of life in women with social phobia". Evidence-based Mental Health 9 (3): 75. doi:10.1136/ebmh.9.3.75. PMID 16868194. http://ebmh.bmj.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=16868194.

- ↑ Mrakotsky C, Masek B, Biederman J, et al. (2008). "Prospective open-label pilot trial of mirtazapine in children and adolescents with social phobia". Journal of Anxiety Disorders 22 (1): 88–97. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.01.005. PMID 17419001.

- ↑ Liappas J, Paparrigopoulos T, Tzavellas E, Christodoulou G (September 2003). "Alcohol detoxification and social anxiety symptoms: a preliminary study of the impact of mirtazapine administration". Journal of Affective Disorders 76 (1-3): 279–84. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00094-0. PMID 12943960. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0165032702000940.

- ↑ Koran LM, Gamel NN, Choung HW, Smith EH, Aboujaoude EN (April 2005). "Mirtazapine for obsessive-compulsive disorder: an open trial followed by double-blind discontinuation". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 66 (4): 515–20. doi:10.4088/JCP.v66n0415. PMID 15816795. http://article.psychiatrist.com/?ContentType=START&ID=10001277.

- ↑ Pallanti S, Quercioli L, Bruscoli M (October 2004). "Response acceleration with mirtazapine augmentation of citalopram in obsessive-compulsive disorder patients without comorbid depression: a pilot study". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 65 (10): 1394–9. doi:10.4088/JCP.v65n1015. PMID 15491244. http://article.psychiatrist.com/?ContentType=START&ID=10001055.

- ↑ Koran LM, Quirk T, Lorberbaum JP, Elliott M (October 2001). "Mirtazapine treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 21 (5): 537–9. doi:10.1097/00004714-200110000-00016. PMID 11593084. http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=0271-0749&volume=21&issue=5&spage=537.

- ↑ Sarchiapone M, Amore M, De Risio S, et al. (January 2003). "Mirtazapine in the treatment of panic disorder: an open-label trial". International Clinical Psychopharmacology 18 (1): 35–8. doi:10.1097/01.yic.0000047780.24295.3e (inactive 2010-03-29). PMID 12490773.

- ↑ Boshuisen ML, Slaap BR, Vester-Blokland ED, den Boer JA (November 2001). "The effect of mirtazapine in panic disorder: an open label pilot study with a single-blind placebo run-in period". International Clinical Psychopharmacology 16 (6): 363–8. doi:10.1097/00004850-200111000-00008. PMID 11712626. http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=0268-1315&volume=16&issue=6&spage=363.

- ↑ Carpenter LL, Leon Z, Yasmin S, Price LH (June 1999). "Clinical experience with mirtazapine in the treatment of panic disorder". Annals of Clinical Psychiatry : Official Journal of the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists 11 (2): 81–6. PMID 10440525.

- ↑ Carli V, Sarchiapone M, Camardese G, Romano L, DeRisio S (July 2002). "Mirtazapine in the treatment of panic disorder". Archives of General Psychiatry 59 (7): 661–2. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.59.7.661. PMID 12090820. http://archpsyc.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12090820.

- ↑ Ribeiro L, Busnello JV, Kauer-Sant'Anna M, et al. (October 2001). "Mirtazapine versus fluoxetine in the treatment of panic disorder". Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research = Revista Brasileira De Pesquisas Médicas E Biológicas / Sociedade Brasileira De Biofísica ... [Et Al.] 34 (10): 1303–7. PMID 11593305. http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0100-879X2001001000010&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en.

- ↑ Davidson JR, Weisler RH, Butterfield MI, et al. (January 2003). "Mirtazapine vs. placebo in posttraumatic stress disorder: a pilot trial". Biological Psychiatry 53 (2): 188–91. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01411-7. PMID 12547477. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0006322302014117.

- ↑ Kim W, Pae CU, Chae JH, Jun TY, Bahk WM (December 2005). "The effectiveness of mirtazapine in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: a 24-week continuation therapy". Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 59 (6): 743–7. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2005.01447.x. PMID 16401254.

- ↑ Bahk WM, Pae CU, Tsoh J, et al. (October 2002). "Effects of mirtazapine in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder in Korea: a pilot study". Human Psychopharmacology 17 (7): 341–4. doi:10.1002/hup.426. PMID 12415552.

- ↑ Chung MY, Min KH, Jun YJ, Kim SS, Kim WC, Jun EM (October 2004). "Efficacy and tolerability of mirtazapine and sertraline in Korean veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized open label trial". Human Psychopharmacology 19 (7): 489–94. doi:10.1002/hup.615. PMID 15378676.

- ↑ Alderman CP, Condon JT, Gilbert AL (July 2009). "An Open-Label Study of Mirtazapine as Treatment for Combat-Related PTSD(July/August)". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy 43 (7): 1220–6. doi:10.1345/aph.1M009. PMID 19584388.

- ↑ Lewis JD (November 2002). "Mirtazapine for PTSD nightmares". The American Journal of Psychiatry 159 (11): 1948–9. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.11.1948-a. PMID 12411239. http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12411239.

- ↑ "Mirtazapine in seasonal affective disorder (SAD): a preliminary report". http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/40002009/abstract.

- ↑ Winokur A, DeMartinis NA, McNally DP, Gary EM, Cormier JL, Gary KA (October 2003). "Comparative effects of mirtazapine and fluoxetine on sleep physiology measures in patients with major depression and insomnia". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 64 (10): 1224–9. doi:10.4088/JCP.v64n1013. PMID 14658972. http://article.psychiatrist.com/?ContentType=START&ID=10000336.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Kim SW, Shin IS, Kim JM, et al. (February 2008). "Effectiveness of mirtazapine for nausea and insomnia in cancer patients with depression". Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 62 (1): 75–83. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.2007.01778.x. PMID 18289144.

- ↑ Cankurtaran ES, Ozalp E, Soygur H, Akbiyik DI, Turhan L, Alkis N (November 2008). "Mirtazapine improves sleep and lowers anxiety and depression in cancer patients: superiority over imipramine". Supportive Care in Cancer : Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer 16 (11): 1291–8. doi:10.1007/s00520-008-0425-1. PMID 18299900.

- ↑ Pae CU (August 2006). "Low-dose mirtazapine may be successful treatment option for severe nausea and vomiting". Progress in Neuro-psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry 30 (6): 1143–5. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.03.015. PMID 16632163.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Kast RE, Foley KF (July 2007). "Cancer chemotherapy and cachexia: mirtazapine and olanzapine are 5-HT3 antagonists with good antinausea effects". European Journal of Cancer Care 16 (4): 351–4. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00760.x. PMID 17587360. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/resolve/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=0961-5423&date=2007&volume=16&issue=4&spage=351.

- ↑ Chen CC, Lin CS, Ko YP, Hung YC, Lao HC, Hsu YW (January 2008). "Premedication with mirtazapine reduces preoperative anxiety and postoperative nausea and vomiting". Anesthesia and Analgesia 106 (1): 109–13, table of contents. doi:10.1213/01.ane.0000289636.09841.bc. PMID 18165563.

- ↑ Teixeira FV, Novaretti TM, Pilon B, Pereira PG, Breda MF (May 2005). "Mirtazapine (Remeron) as treatment for non-mechanical vomiting after gastric bypass". Obesity Surgery 15 (5): 707–9. doi:10.1381/0960892053923923. PMID 15946465.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Ito T, Okubo Y, Roth A (April 2009). "[Efficacy of mirtazapine for appetite loss and nausea of the cancer patient--from clinical experience in Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center"] (in Japanese). Gan to Kagaku Ryoho. Cancer & Chemotherapy 36 (4): 623–6. PMID 19381036. http://www.pier-online.jp/abstract.php?issn=0385-0684&volume=36&issue=4&spage=623.

- ↑ Thompson DS (2000). "Mirtazapine for the treatment of depression and nausea in breast and gynecological oncology". Psychosomatics 41 (4): 356–9. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.41.4.356. PMID 10906359. http://psy.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10906359.

- ↑ Mattox TW (August 2005). "Treatment of unintentional weight loss in patients with cancer". Nutrition in Clinical Practice : Official Publication of the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 20 (4): 400–10. PMID 16207680. http://ncp.sagepub.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=16207680.

- ↑ Fox CB, Treadway AK, Blaszczyk AT, Sleeper RB (April 2009). "Megestrol acetate and mirtazapine for the treatment of unplanned weight loss in the elderly". Pharmacotherapy 29 (4): 383–97. doi:10.1592/phco.29.4.383. PMID 19323618.

- ↑ Davis MP, Frandsen JL, Walsh D, Andresen S, Taylor S (March 2003). "Mirtazapine for pruritus". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 25 (3): 288–91. doi:10.1016/S0885-3924(02)00645-0. PMID 12614964. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0885392402006450.

- ↑ Hundley JL, Yosipovitch G (June 2004). "Mirtazapine for reducing nocturnal itch in patients with chronic pruritus: a pilot study". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 50 (6): 889–91. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.01.045. PMID 15153889.

- ↑ Demierre MF, Taverna J (September 2006). "Mirtazapine and gabapentin for reducing pruritus in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 55 (3): 543–4. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.04.025. PMID 16908377.

- ↑ Sheen MJ, Ho ST, Lee CH, Tsung YC, Chang FL, Huang ST (November 2008). "Prophylactic mirtazapine reduces intrathecal morphine-induced pruritus". British Journal of Anaesthesia 101 (5): 711–5. doi:10.1093/bja/aen241. PMID 18713761.

- ↑ Castillo JL, Menendez P, Segovia L, Guilleminault C (September 2004). "Effectiveness of mirtazapine in the treatment of sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome (SAHS)". Sleep Medicine 5 (5): 507–8. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2004.06.004. PMID 15341898.

- ↑ Carley DW, Olopade C, Ruigt GS, Radulovacki M (January 2007). "Efficacy of mirtazapine in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome". Sleep 30 (1): 35–41. PMID 17310863.

- ↑ Marshall NS, Yee BJ, Desai AV, et al. (June 2008). "Two randomized placebo-controlled trials to evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of mirtazapine for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea". Sleep 31 (6): 824–31. PMID 18548827.

- ↑ Brunner H (August 2008). "Success and failure of mirtazapine as alternative treatment in elderly stroke patients with sleep apnea-a preliminary open trial". Sleep & Breathing = Schlaf & Atmung 12 (3): 281–5. doi:10.1007/s11325-008-0177-7. PMID 18369672.

- ↑ Carley DW, Radulovacki M (December 1999). "Mirtazapine, a mixed-profile serotonin agonist/antagonist, suppresses sleep apnea in the rat". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 160 (6): 1824–9. PMID 10588592. http://ajrccm.atsjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10588592.

- ↑ Lévy E, Margolese HC (September 2003). "Migraine headache prophylaxis and treatment with low-dose mirtazapine". International Clinical Psychopharmacology 18 (5): 301–3. doi:10.1097/01.yic.0000080803.87368.01 (inactive 2010-03-29). PMID 12920393.

- ↑ Brannon GE, Rolland PD, Gary JM (2000). "Use of mirtazapine as prophylactic treatment for migraine headache". Psychosomatics 41 (2): 153–4. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.41.2.153. PMID 10749956. http://psy.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10749956.

- ↑ Bendtsen L, Jensen R (May 2004). "Mirtazapine is effective in the prophylactic treatment of chronic tension-type headache". Neurology 62 (10): 1706–11. PMID 15159466. http://www.neurology.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15159466.

- ↑ Bendtsen L, Buchgreitz L, Ashina S, Jensen R (February 2007). "Combination of low-dose mirtazapine and ibuprofen for prophylaxis of chronic tension-type headache". European Journal of Neurology : the Official Journal of the European Federation of Neurological Societies 14 (2): 187–93. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01607.x. PMID 17250728.

- ↑ Martín-Araguz A, Bustamante-Martínez C, de Pedro-Pijoán JM (2003). "[Treatment of chronic tension type headache with mirtazapine and amitriptyline"] (in Spanish; Castilian). Revista De Neurologia 37 (2): 101–5. PMID 12938066. http://www.revneurol.com/LinkOut/formMedLine.asp?Refer=2002498&Revista=Revneurol.

- ↑ Sheen MJ, Ho ST (July 2008). "Mirtazapine relieves postdural puncture headache". Anesthesia and Analgesia 107 (1): 346. doi:10.1213/ane.0b013e3181771074. PMID 18635514.

- ↑ Nutt D, Law J (September 1999). "Treatment of cluster headache with mirtazapine". Headache 39 (8): 586–7. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4610.1999.t01-1-3908586.x. PMID 11279976. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/resolve/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=0017-8748&date=1999&volume=39&issue=8&spage=586.

- ↑ Guclu S, Gol M, Dogan E, Saygili U (October 2005). "Mirtazapine use in resistant hyperemesis gravidarum: report of three cases and review of the literature". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics 272 (4): 298–300. doi:10.1007/s00404-005-0007-0. PMID 16007504.

- ↑ Rohde A, Dembinski J, Dorn C (August 2003). "Mirtazapine (Remergil) for treatment resistant hyperemesis gravidarum: rescue of a twin pregnancy". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics 268 (3): 219–21. doi:10.1007/s00404-003-0502-0. PMID 12819986.

- ↑ Schwarzer V, Heep A, Gembruch U, Rohde A (January 2008). "Treatment resistant hyperemesis gravidarum in a patient with type 1 diabetes mellitus: neonatal withdrawal symptoms after successful antiemetic therapy with mirtazapine". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics 277 (1): 67–9. doi:10.1007/s00404-007-0406-5. PMID 17628816.

- ↑ "Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Mirtazapine -- THOMAS 157 (8): 1341 -- Am J Psychiatry". http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/157/8/1341-a.

- ↑ Thomas SG (August 2000). "Irritable bowel syndrome and mirtazapine". The American Journal of Psychiatry 157 (8): 1341–2. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.157.8.1341-a. PMID 10910804. http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10910804.

- ↑ Kim SW, Shin IS, Kim JM, et al. (2006). "Mirtazapine for severe gastroparesis unresponsive to conventional prokinetic treatment". Psychosomatics 47 (5): 440–2. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.47.5.440. PMID 16959934.

- ↑ Han C, Pae CU, Lee BH, et al. (2008). "Venlafaxine versus mirtazapine in the treatment of undifferentiated somatoform disorder: a 12-week prospective, open-label, randomized, parallel-group trial". Clinical Drug Investigation 28 (4): 251–61. PMID 18345715.

- ↑ Posey DJ, Guenin KD, Kohn AE, Swiezy NB, McDougle CJ (2001). "A naturalistic open-label study of mirtazapine in autistic and other pervasive developmental disorders". Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 11 (3): 267–77. doi:10.1089/10445460152595586. PMID 11642476.

- ↑ Coskun M, Karakoc S, Kircelli F, Mukaddes NM (April 2009). "Effectiveness of mirtazapine in the treatment of inappropriate sexual behaviors in individuals with autistic disorder". Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 19 (2): 203–6. doi:10.1089/cap.2008.020. PMID 19364298.

- ↑ Coskun M, Mukaddes NM (April 2008). "Mirtazapine treatment in a subject with autistic disorder and fetishism". Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 18 (2): 206–9. doi:10.1089/cap.2007.0014. PMID 18439117.

- ↑ Albertini G, Polito E, Sarà M, Di Gennaro G, Onorati P (May 2006). "Compulsive masturbation in infantile autism treated by mirtazapine". Pediatric Neurology 34 (5): 417–8. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2005.10.023. PMID 16648008.

- ↑ Nguyen M, Murphy T (August 2001). "Mirtazapine for excessive masturbation in an adolescent with autism". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 40 (8): 868–9. doi:10.1097/00004583-200108000-00004. PMID 11501682. http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=0890-8567&volume=40&issue=8&spage=868.

- ↑ "Mirtazapine for Neuroleptic-Induced Akathisia -- POYUROVSKY and WEIZMAN 158 (5): 819 -- Am J Psychiatry". http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/158/5/819.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Poyurovsky M, Epshtein S, Fuchs C, Schneidman M, Weizman R, Weizman A (June 2003). "Efficacy of low-dose mirtazapine in neuroleptic-induced akathisia: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled pilot study". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 23 (3): 305–8. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000084027.22282.16 (inactive 2010-03-29). PMID 12826992.

- ↑ Poyurovsky M, Pashinian A, Weizman R, Fuchs C, Weizman A (June 2006). "Low-dose mirtazapine: a new option in the treatment of antipsychotic-induced akathisia. A randomized, double-blind, placebo- and propranolol-controlled trial". Biological Psychiatry 59 (11): 1071–7. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.12.007. PMID 16497273.

- ↑ Hieber R, Dellenbaugh T, Nelson LA (June 2008). "Role of mirtazapine in the treatment of antipsychotic-induced akathisia". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy 42 (6): 841–6. doi:10.1345/aph.1K672. PMID 18460588.

- ↑ Ranjan S, Chandra PS, Chaturvedi SK, Prabhu SC, Gupta A (April 2006). "Atypical antipsychotic-induced akathisia with depression: therapeutic role of mirtazapine". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy 40 (4): 771–4. doi:10.1345/aph.1G561. PMID 16569791.

- ↑ Poyurovsky M, Weizman A (May 2001). "Mirtazapine for neuroleptic-induced akathisia". The American Journal of Psychiatry 158 (5): 819. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.819. PMID 11329417. http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11329417.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 Fernández J, Alonso JM, Andrés JI, et al. (March 2005). "Discovery of new tetracyclic tetrahydrofuran derivatives as potential broad-spectrum psychotropic agents". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 48 (6): 1709–12. doi:10.1021/jm049632c. PMID 15771415.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 de Boer TH, Maura G, Raiteri M, de Vos CJ, Wieringa J, Pinder RM (April 1988). "Neurochemical and autonomic pharmacological profiles of the 6-aza-analogue of mianserin, Org 3770 and its enantiomers". Neuropharmacology 27 (4): 399–408. doi:10.1016/0028-3908(88)90149-9. PMID 3419539.

- ↑ de Boer T (1996). "The pharmacologic profile of mirtazapine". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57 Suppl 4: 19–25. PMID 8636062.

- ↑ Kooyman AR, Zwart R, Vanderheijden PM, Van Hooft JA, Vijverberg HP (1994). "Interaction between enantiomers of mianserin and ORG3770 at 5-HT3 receptors in cultured mouse neuroblastoma cells". Neuropharmacology 33 (3-4): 501–7. doi:10.1016/0028-3908(94)90081-7. PMID 7984289.

- ↑ Boess FG, Monsma FJ, Carolo C, et al. (1997). "Functional and radioligand binding characterization of rat 5-HT6 receptors stably expressed in HEK293 cells". Neuropharmacology 36 (4-5): 713–20. doi:10.1016/S0028-3908(97)00019-1. PMID 9225298.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 76.2 76.3 76.4 76.5 76.6 76.7 Anttila SA, Leinonen EV (2001). "A review of the pharmacological and clinical profile of mirtazapine". CNS Drug Reviews 7 (3): 249–64. PMID 11607047.

- ↑ "The α2-adrenoceptor antagonist Org 3770 enhances serotonin transmission in vivo". http://cat.inist.fr/?aModele=afficheN&cpsidt=3960842.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 Berendsen HH, Broekkamp CL (October 1997). "Indirect in vivo 5-HT1A-agonistic effects of the new antidepressant mirtazapine". Psychopharmacology 133 (3): 275–82. doi:10.1007/s002130050402. PMID 9361334. http://link.springer.de/link/service/journals/00213/bibs/7133003/71330275.htm.

- ↑ Nakayama K, Sakurai T, Katsu H (April 2004). "Mirtazapine increases dopamine release in prefrontal cortex by 5-HT1A receptor activation". Brain Research Bulletin 63 (3): 237–41. doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2004.02.007. PMID 15145142. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0361923004000589.

- ↑ Blier P, Abbott FV (January 2001). "Putative mechanisms of action of antidepressant drugs in affective and anxiety disorders and pain". Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience : JPN 26 (1): 37–43. PMID 11212592. PMC 1408043. http://www.cma.ca/multimedia/staticContent/HTML/N0/l2/jpn/vol-26/issue-1/pdf/pg37.pdf.

- ↑ Dekeyne A, Millan MJ (April 2009). "Discriminative stimulus properties of the atypical antidepressant, mirtazapine, in rats: a pharmacological characterization". Psychopharmacology 203 (2): 329–41. doi:10.1007/s00213-008-1259-8. PMID 18709360.

- ↑ Millan MJ (2005). "Serotonin 5-HT2C receptors as a target for the treatment of depressive and anxious states: focus on novel therapeutic strategies". Thérapie 60 (5): 441–60. doi:10.2515/therapie:2005065. PMID 16433010.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 83.2 "www.psychotropical.com". http://www.psychotropical.com/Antidepressants_mirtazapine.shtml.

- ↑ De Deurwaerdère P, Navailles S, Berg KA, Clarke WP, Spampinato U (March 2004). "Constitutive activity of the serotonin2C receptor inhibits in vivo dopamine release in the rat striatum and nucleus accumbens". The Journal of Neuroscience : the Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience 24 (13): 3235–41. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0112-04.2004. PMID 15056702.

- ↑ Bubar MJ, Cunningham KA (April 2007). "Distribution of serotonin 5-HT2C receptors in the ventral tegmental area". Neuroscience 146 (1): 286–97. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.12.071. PMID 17367945.

- ↑ Millan MJ, Gobert A, Rivet JM, et al. (March 2000). "Mirtazapine enhances frontocortical dopaminergic and corticolimbic adrenergic, but not serotonergic, transmission by blockade of alpha2-adrenergic and serotonin2C receptors: a comparison with citalopram". The European Journal of Neuroscience 12 (3): 1079–95. doi:10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00982.x. PMID 10762339. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/resolve/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=0953-816X&date=2000&volume=12&issue=3&spage=1079.

- ↑ Millan MJ, Gobert A, Lejeune F, et al. (September 2003). "The novel melatonin agonist agomelatine (S20098) is an antagonist at 5-hydroxytryptamine2C receptors, blockade of which enhances the activity of frontocortical dopaminergic and adrenergic pathways". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 306 (3): 954–64. doi:10.1124/jpet.103.051797. PMID 12750432.

- ↑ "February 2009: agomelatine (Valdoxan) licensed in the EU to treat major depression". http://www.agomelatine.org/2009-valdoxan.html.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 89.2 89.3 89.4 89.5 Fawcett J, Barkin RL (December 1998). "Review of the results from clinical studies on the efficacy, safety and tolerability of mirtazapine for the treatment of patients with major depression". Journal of Affective Disorders 51 (3): 267–85. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(98)00224-9. PMID 10333982. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0165-0327(98)00224-9.

- ↑ Kast RE (September 2001). "Mirtazapine may be useful in treating nausea and insomnia of cancer chemotherapy". Supportive Care in Cancer : Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer 9 (6): 469–70. PMID 11585276. http://link.springer.de/link/service/journals/00520/bibs/1009006/10090469.htm.

- ↑ "The psychopharmacology of 5-HT3 receptors". http://cat.inist.fr/?aModele=afficheN&cpsidt=4556300.

- ↑ Nowakowska E, Chodera A, Kus K (1999). "Behavioral and memory improving effects of mirtazapine in rats". Polish Journal of Pharmacology 51 (6): 463–9. PMID 10817523.

- ↑ Roychoudhury M, Kulkarni SK (1997). "Effects of ondansetron on short-term memory retrieval in mice". Methods and Findings in Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology 19 (1): 43–6. PMID 9098839.

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 94.2 McGrath PJ, Stewart JW, Fava M, et al. (September 2006). "Tranylcypromine versus venlafaxine plus mirtazapine following three failed antidepressant medication trials for depression: a STAR*D report". The American Journal of Psychiatry 163 (9): 1531–41; quiz 1666. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.9.1531. PMID 16946177. http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=16946177.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 Sennef C, Timmer CJ, Sitsen JM (March 2003). "Mirtazapine in combination with amitriptyline: a drug-drug interaction study in healthy subjects". Human Psychopharmacology 18 (2): 91–101. doi:10.1002/hup.441. PMID 12590402.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 Gándara Martín Jde L, Agüera Ortiz L, Ferre Navarrete F, Rojo Rodés E, Ros Montalbán S (2002). "[Tolerability and efficacy of combined antidepressant therapy"] (in Spanish; Castilian). Actas Españolas De Psiquiatría 30 (2): 75–84. PMID 12028939. http://www.arsxxi.com/Revistas/mostrararticulo.php?idarticulo=13031118.

- ↑ Caldis EV, Gair RD (October 2004). "Mirtazapine for treatment of nausea induced by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie 49 (10): 707. PMID 15560319.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 Ravindran LN, Eisfeld BS, Kennedy SH (February 2008). "Combining mirtazapine and duloxetine in treatment-resistant depression improves outcomes and sexual function". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 28 (1): 107–8. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e318160d609. PMID 18204355.

- ↑ Rao DVSN, Dandala R, Bharathi C, Handa VK, Sivakumaran M, Naidu A (Dec 2006). "Synthesis of potential related substances of mirtazapine". Arkivoc 2006: 127–132. http://www.arkat-usa.org/get-file/22868/.

- ↑ US patent 4062848, Van der Burg WJ, "Tetracyclic compounds", published 1977-12-13, issued 1977-12-13

- ↑ Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. (February 2009). "Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis". Lancet 373 (9665): 746–58. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60046-5. PMID 19185342. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140-6736(09)60046-5.

- ↑ Croom KF, Perry CM, Plosker GL.[1].CNSDrugs;2009 23(5):427-452. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200923050-00006.

- ↑ van Moffaert M, de Wilde J, Vereecken A, et al. (March 1995). "Mirtazapine is more effective than trazodone: a double-blind controlled study in hospitalized patients with major depression". International Clinical Psychopharmacology 10 (1): 3–9. doi:10.1097/00004850-199503000-00001. PMID 7622801.

- ↑ Bruijn JA, Moleman P, Mulder PG, et al. (October 1996). "A double-blind, fixed blood-level study comparing mirtazapine with imipramine in depressed in-patients". Psychopharmacology 127 (3): 231–7. PMID 8912401. http://link.springer.de/link/service/journals/00213/bibs/6127003/61270231.htm.

- ↑ Bruijn JA, Moleman P, Mulder PG, van den Broek WW (May 1999). "Depressed in-patients respond differently to imipramine and mirtazapine". Pharmacopsychiatry 32 (3): 87–92. doi:10.1055/s-2007-979200. PMID 10463374.

- ↑ Medications or Substances causing Excessive hunger http://www.wrongdiagnosis.com/symptoms/excessive_hunger/side-effects.htm

- ↑ Kim SW, Shin IS, Kim JM, Park KH, Youn T, Yoon JS (October 2008). "Factors potentiating the risk of mirtazapine-associated restless legs syndrome". Human Psychopharmacology 23 (7): 615–20. doi:10.1002/hup.965. PMID 18756499.

- ↑ Montgomery SA (December 1995). "Safety of mirtazapine: a review". International Clinical Psychopharmacology 10 Suppl 4: 37–45. PMID 8930008.

- ↑ 109.0 109.1 Biswas PN, Wilton LV, Shakir SA (March 2003). "The pharmacovigilance of mirtazapine: results of a prescription event monitoring study on 13554 patients in England". Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England) 17 (1): 121–6. PMID 12680749. http://jop.sagepub.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12680749.

- ↑ Thase ME; Nierenberg, AA; Vrijland, P; Van Oers, HJ; Schutte, AJ; Simmons, JH (July 2010). "Remission with mirtazapine and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from 15 controlled trials of acute phase treatment of major depression.". Int Clin Psychopharmacol 25 (4): 189–98. doi:10.1097/YIC.0b013e328330adb2. PMID 20531012. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20531012.

- ↑ 111.0 111.1 Benazzi F (June 1998). "Mirtazapine withdrawal symptoms". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie 43 (5): 525. PMID 9653542.

- ↑ 112.0 112.1 Berigan TR (June 2001). "Mirtazapine-Associated Withdrawal Symptoms: A Case Report". Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 3 (3): 143. PMID 15014614.

- ↑ Blier P (2001). "Pharmacology of rapid-onset antidepressant treatment strategies". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 62 Suppl 15: 12–7. PMID 11444761.

- ↑ van Broekhoven F, Kan CC, Zitman FG (June 2002). "Dependence potential of antidepressants compared to benzodiazepines". Progress in Neuro-psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry 26 (5): 939–43. doi:10.1016/S0278-5846(02)00209-9. PMID 12369270. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0278-5846(02)00209-9.

- ↑ Vlaminck JJ, van Vliet IM, Zitman FG (March 2005). "[Withdrawal symptoms of antidepressants]" (in Dutch; Flemish). Nederlands Tijdschrift Voor Geneeskunde 149 (13): 698–701. PMID 15819135.

- ↑ Klesmer J, Sarcevic A, Fomari V (August 2000). "Panic attacks during discontinuation of mirtazepine". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie 45 (6): 570–1. PMID 10986577.

- ↑ MacCall C, Callender J (October 1999). "Mirtazapine withdrawal causing hypomania". The British Journal of Psychiatry : the Journal of Mental Science 175: 390. doi:10.1192/bjp.175.4.390a. PMID 10789310.

- ↑ Ali S, Milev R (May 2003). "Switch to mania upon discontinuation of antidepressants in patients with mood disorders: a review of the literature". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie 48 (4): 258–64. PMID 12776393.

- ↑ Hoes MJ, Zeijpveld JH (March 1996). "Mirtazapine as treatment for serotonin syndrome". Pharmacopsychiatry 29 (2): 81. doi:10.1055/s-2007-979550. PMID 8741027.

- ↑ Gillman PK (June 2006). "A review of serotonin toxicity data: implications for the mechanisms of antidepressant drug action". Biological Psychiatry 59 (11): 1046–51. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.11.016. PMID 16460699. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0006-3223(05)01441-1.

- ↑ Abo-Zena RA, Bobek MB, Dweik RA (April 2000). "Hypertensive urgency induced by an interaction of mirtazapine and clonidine.". Pharmacotherapy 20 (4): 476–8. doi:10.1592/phco.20.5.476.35061. PMID 10772378.

- ↑ Velazquez C, Carlson A, Stokes KA, Leikin JB (December 2001). "Relative safety of mirtazapine overdose". Veterinary and Human Toxicology 43 (6): 342–4. PMID 11757992.

- ↑ Holzbach R, Jahn H, Pajonk FG, Mähne C (November 1998). "Suicide attempts with mirtazapine overdose without complications". Biological Psychiatry 44 (9): 925–6. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(98)00081-X. PMID 9807651. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0006-3223(98)00081-X.

- ↑ Retz W, Maier S, Maris F, Rösler M (November 1998). "Non-fatal mirtazapine overdose". International Clinical Psychopharmacology 13 (6): 277–9. doi:10.1097/00004850-199811000-00007. PMID 9861579.

- ↑ P. Nikolaou, A. Dona, I. Papoutsis et al. Death due to mirtazapine overdose. Clin. Toxicol. 47: 453, 2009.

- ↑ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 1045-1047.

- ↑ Buckley N, McManus P (December 2002). "Fatal toxicity of serotinergic antidepressants". BMJ 325 (7376): 1332–3. PMID 12468481. PMC 137809. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12468481.

Further reading

- Stimmel GL, Dopheide JA, Stahl SM (1997). "Mirtazapine: an antidepressant with noradrenergic and specific serotonergic effects". Pharmacotherapy 17 (1): 10–21. PMID 9017762.

- Croom KF, Perry CM, Plosker GL (2009). "Mirtazapine: a review of its use in major depression and other psychiatric disorders". CNS Drugs 23 (5): 427–52. doi:10.2165/00023210-200923050-00006. PMID 19453203. http://content.wkhealth.com/linkback/openurl?issn=1172-7047&volume=23&issue=5&spage=427.

- Anttila SA, Leinonen EV (2001). "A review of the pharmacological and clinical profile of mirtazapine". CNS Drug Reviews 7 (3): 249–64. PMID 11607047.

- Timmer CJ, Sitsen JM, Delbressine LP (June 2000). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of mirtazapine". Clinical Pharmacokinetics 38 (6): 461–74. doi:10.2165/00003088-200038060-00001. PMID 10885584. http://content.wkhealth.com/linkback/openurl?issn=0312-5963&volume=38&issue=6&spage=461.

External links

- Mirtazapine - Drugs.com

- Remeron - Rxlist.com

- Mirtazapine - MedicineNet.com

- Mirtazapine - MedlinePlus

- Mirtazapine - About.com

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal - Mirtazapine

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Navbox with collapsible sections

|

|||||||||||||||||