Minimalism

Minimalism describes movements in various forms of art and design, especially visual art and music, where the work is stripped down to its most fundamental features. As a specific movement in the arts it is identified with developments in post-World War II Western Art, most strongly with American visual arts in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Prominent artists associated with this movement include Donald Judd, John McLaughlin, Agnes Martin, Dan Flavin, Robert Morris, Anne Truitt, and Frank Stella. It is rooted in the reductive aspects of Modernism, and is often interpreted as a reaction against Abstract expressionism and a bridge to Postmodern art practices.

The terms have expanded to encompass a movement in music which features repetition and iteration, as in the compositions of La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, Philip Glass, and John Adams. (See also Postminimalism).

The term "minimalist" is often applied colloquially to designate anything which is spare or stripped to its essentials. It has also been used to describe the plays and novels of Samuel Beckett, the films of Robert Bresson, the stories of Raymond Carver, and even the automobile designs of Colin Chapman. The word was first used in English in the early twentieth century to describe the Mensheviks.[1]

Contents |

Minimalist music

- See Minimalist music for a full discussion.

Minimalist design

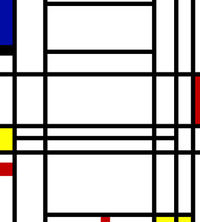

The term minimalism is also used to describe a trend in design and architecture where in the subject is reduced to its necessary elements. Minimalist design has been highly influenced by Japanese traditional design and architecture. In addition, the work of De Stijl artists is a major source of reference for this kind of work. De Stijl expanded the ideas that could be expressed by using basic elements such as lines and planes organized in very particular manners.

Architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe adopted the motto "Less is more" to describe his aesthetic tactic of arranging the numerous necessary components of a building to create an impression of extreme simplicity, by enlisting every element and detail to serve multiple visual and functional purposes (such as designing a floor to also serve as the radiator, or a massive fireplace to also house the bathroom). Designer Buckminster Fuller adopted the engineer's goal of "Doing more with less", but his concerns were oriented towards technology and engineering rather than aesthetics. A similar sentiment was industrial designer Dieter Rams' motto, "Less but better" adapted from van der Rohe. The structure uses relatively simple elegant designs; ornamentations are quality rather than quantity. The structure's beauty is also determined by playing with lighting, using the basic geometric shapes as outlines, using only a single shape or a small number of like shapes for components for design unity, using tasteful non-fussy bright color combinations, usually natural textures and colors, and clean and fine finishes. Using sometimes the beauty of natural patterns on stone cladding and real wood encapsulated within ordered simplified structures, and real metal producing a simplified but prestigious architecture and interior design. May use color brightness balance and contrast between surface colors to improve visual aesthetics. The structure would usually have industrial and space age style utilities (lamps, stoves, stairs, technology, etcetera), neat and straight components (like walls or stairs) that appear to be machined with machines, flat or nearly flat roofs, pleasing negative spaces, and large windows to let in lots of sunlight. This and science fiction may have contributed to the late twentieth century futuristic architecture design, and modern home decor. Modern minimalist home architecture with its unnecessary internal walls removed may have led to the popularity of the open plan kitchen and living room style.

Another modern master who exemplifies reductivist ideas is Luis Barragán. In minimalism, the architectural designers pay special attention to the connection between perfect planes, elegant lighting, and careful consideration of the void spaces left by the removal of three-dimensional shapes from an architectural design. The more attractive looking minimalist home designs are not truly minimalist, because these use more expensive building materials and finishes, and are relatively larger.

Contemporary architects working in this tradition include John Pawson, Eduardo Souto de Moura, Álvaro Siza Vieira, Tadao Ando, Alberto Campo Baeza, Yoshio Taniguchi, Peter Zumthor, Hugh Newell Jacobsen, Vincent Van Duysen, Claudio Silvestrin, Michael Gabellini, and Richard Gluckman.[2]

Minimalism in visual art

Minimalism in visual art, sometimes referred to as literalist art[3] and ABC Art[4] emerged in New York in the 1960s. It is regarded as a reaction against the painterly forms of Abstract Expressionism as well as the discourse, institutions and ideologies that supported it. As artist and critic Thomas Lawson noted in his 1977 catalog essay Last Exit: Painting, minimalism did not reject Clement Greenberg's claims about Modernist Painting's reduction to surface and materials so much as take his claims literally. Minimalism was the result, even though the term "minimalism" was not generally embraced by the artists associated with it, and many practitioners of art designated minimalist by critics did not identify it as a movement as such.

In contrast to the Abstract Expressionists, Minimalists were influenced by composers John Cage and LaMonte Young, poet William Carlos Williams, and the landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted. They very explicitly stated that their art was not self-expression, in opposition to the previous decade's Abstract Expressionists. In general, Minimalism's features included geometric, often cubic forms purged of much metaphor, equality of parts, repetition, neutral surfaces, and industrial materials.

Robert Morris, an influential theorist and artist, wrote a three part essay, "Notes on Sculpture 1-3", originally published across three issues of Artforum in 1966. In these essays, Morris attempted to define a conceptual framework and formal elements for himself and one that would embrace the practices of his contemporaries. These essays paid great attention to the idea of the gestalt - "parts... bound together in such a way that they create a maximum resistance to perceptual separation." Morris later described an art represented by a "marked lateral spread and no regularized units or symmetrical intervals..." in "Notes on Sculpture 4: Beyond Objects", originally published in Artforum, 1969, continuing to say that "indeterminacy of arrangement of parts is a literal aspect of the physical existence of the thing." The general shift in theory of which this essay is an expression suggests the transitions into what would later be referred to as Postminimalism.

One of the first artists specifically associated with Minimalism was the painter, Frank Stella, whose early "stripe" paintings were highlighted in the 1959 show, "16 Americans", organized by Dorothy Miller at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The width of the stripes in Frank Stellas's stripe paintings were determined by the dimensions of the lumber, visible as the depth of the painting when viewed from the side, used to construct the supportive chassis upon which the canvas was stretched. The decisions about structures on the front surface of the canvas were therefore not entirely subjective, but pre-conditioned by a "given" feature of the physical construction of the support. In the show catalog, Carl Andre noted, "Art excludes the unnecessary. Frank Stella has found it necessary to paint stripes. There is nothing else in his painting." These reductive works were in sharp contrast to the energy-filled and apparently highly subjective and emotionally-charged paintings of Willem de Kooning or Franz Kline and, in terms of precedent among the previous generation of abstract expressionists, leaned more toward less gestural, often somber coloristic field paintings of Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko. Although Stella received immediate attention from the MOMA show, artists like Kenneth Noland, Ralph Humphrey, Robert Motherwell and Robert Ryman had begun to explore stripes, monochromatic and Hard-edge formats from the late 50s through the 1960s.[5]

Because of a tendency in Minimalism to exclude the pictorial, illusionistic and fictive in favor of the literal, there was a movement away from painterly and toward sculptural concerns. Donald Judd had started as a painter, and ended as a creator of objects. His seminal essay, "Specific Objects" (published in Arts Yearbook 8, 1965), was a touchstone of theory for the formation of Minimalist aesthetics. In this essay, Judd found a starting point for a new territory for American art, and a simultaneous rejection of residual inherited European artistic values. He pointed to evidence of this development in the works of an array of artists active in New York at the time, including Jasper Johns, Dan Flavin and Lee Bontecou. Of "preliminary" importance for Judd was the work of George Ortman [1], who had concretized and distilled painting's forms into blunt, tough, philosophically charged geometries. These Specific Objects inhabited a space not then comfortably classifiable as either painting or sculpture. That the categorical identity of such objects was itself in question, and that they avoided easy association with well-worn and over-familiar conventions, was a part of their value for Judd.

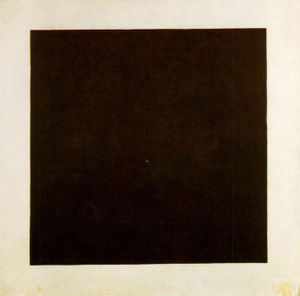

In a much more broad and general sense, one might, in fact, find European roots of Minimalism in the geometric abstractions painters in the Bauhaus, in the works of Piet Mondrian and other artists associated with the movement DeStijl, in Russian Constructivists and in the work of the Romanian sculptor Constantin Brâncuşi.

This movement was heavily criticised by high modernist formalist art critics and historians. Some anxious critics thought Minimalist art represented a misunderstanding of the modern dialectic of painting and sculpture as defined by critic Clement Greenberg, arguably the dominant American critic of painting in the period leading up to the 1960s. The most notable critique of Minimalism was produced by Michael Fried, a Greenbergian critic, who objected to the work on the basis of its "theatricality". In Art and Objecthood (published in Artforum in June 1967) he declared that the Minimalist work of art, particularly Minimalist sculpture, was based on an engagement with the physicality of the spectator. He argued that work like Robert Morris's transformed the act of viewing into a type of spectacle, in which the artifice of the act observation and the viewer's participation in the work were unveiled. Fried saw this displacement of the viewer's experience from an aesthetic engagement within, to an event outside of the artwork as a failure of Minimal art. Fried's opinionated essay was immediately challenged by artist Robert Smithson in a letter to the editor in the October issue of Artforum. Smithson stated the following: "What Fried fears most is the consciousness of what he is doing--namely being himself theatrical."

Other Minimalist artists include: Richard Allen, Walter Darby Bannard, Larry Bell, Ronald Bladen, Mel Bochner, Norman Carlberg, Erwin Hauer, Dan Flavin, Sol LeWitt, Brice Marden, Agnes Martin, Jo Baer, John McCracken, Paul Mogensen, David Novros, Ad Reinhardt, Fred Sandback, Richard Serra, Tony Smith, Robert Smithson, and Anne Truitt.

Ad Reinhardt, actually an artist of the Abstract Expressionist generation, but one whose reductive nearly all-black paintings seemed to anticipate minimalism, had this to say about the value of a reductive approach to art: "The more stuff in it, the busier the work of art, the worse it is. More is less. Less is more. The eye is a menace to clear sight. The laying bare of oneself is obscene. Art begins with the getting rid of nature."

Literary minimalism

Literary minimalism is characterized by an economy with words and a focus on surface description. Minimalist authors eschew adverbs and prefer allowing context to dictate meaning. Readers are expected to take an active role in the creation of a story, to "choose sides" based on oblique hints and innuendo, rather than reacting to directions from the author. The characters in minimalist stories and novels tend to be unexceptional.

Some 1940s-era crime fiction of writers such as James M. Cain and Jim Thompson adopted a stripped-down, matter-of-fact prose style to considerable effect; some classifiy this prose style as minimalism.

Another strand of literary minimalism arose in response to the Metafiction trend of the 1960s and early 1970s (John Barth, Robert Coover, and William H. Gass). These writers were also spare with prose and kept a psychological distance from their subject matter.

Minimalist authors, or those who are identified with minimalism during certain periods of their writing careers, include the following: Raymond Carver, Ann Beattie, Bret Easton Ellis, Chuck Palahniuk, Charles Bukowski, Ernest Hemingway, K. J. Stevens, Amy Hempel, Bobbie Ann Mason, Tobias Wolff, Grace Paley, Sandra Cisneros, Mary Robison, Frederick Barthelme, Richard Ford, and Alicia Erian.

American poets such as William Carlos Williams, early Ezra Pound, Robert Creeley, Robert Grenier, and Aram Saroyan are sometimes identified with their minimalist style. The term "minimalism" is also sometimes associated with the briefest of poetic genres, haiku, which originated in Japan but has been domesticated in English literature by poets such as Nick Virgilio, Raymond Roseliep, and George Swede.

The Irish author Samuel Beckett is also known for his minimalist plays and prose, as is the Norwegian writer Jon Fosse.

See also

|

|

Footnotes

- ↑ New Oxford American Dictionary (2nd ed., 2005), p. 1079.

- ↑ Holm, Ivar (2006). Ideas and Beliefs in Architecture and Industrial design: How attitudes, orientations, and underlying assumptions shape the built environment. Oslo School of Architecture and Design. ISBN 8254701741.

- ↑ Fried, M. "Art and Objecthood", Artforum, 1967

- ↑ Rose, B. "ABC Art", Art in America, 1965.

- ↑ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/384056/minimalism

External links

- Article on Minimalist Art at the Dia Beacon Museum"Dia Beacon", Tiziano Thomas Dossena, Bridge Apulia USA N.9, 2003

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||||