Mimesis

Mimesis (Ancient Greek: μίμησις from μιμεῖσθαι) is a critical and philosophical term that carries a wide range of meanings, which include: imitation, representation, mimicry, imitatio, nonsensuous similarity, the act of resembling, the act of expression, and the presentation of the self.[1] Mimesis has been theorised by Plato, Aristotle, Philip Sidney, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Sigmund Freud, Walter Benjamin, Theodor Adorno, Erich Auerbach, Luce Irigaray, René Girard, Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe, Michael Taussig, Merlin Donald, Paul Ricoeur, and Homi Bhabha.

Contents |

Classical definitions

Plato

Both Plato and Aristotle saw in mimesis (Greek μίμησις) the representation of nature. Plato wrote about mimesis in both Ion and The Republic (Books II, III and X). In Ion, he states that poetry is the art of divine madness, or inspiration. Because the poet is subject to this divine madness, it is not his/her function to convey the truth. As Plato has it, truth is the concern of the philosopher only. As culture in those days did not consist in the solitary reading of books, but in the listening to performances, the recitals of orators (and poets), or the acting out by classical actors of tragedy, Plato maintained in his critique that theatre was not sufficient in conveying the truth. He was concerned that actors or orators were thus able to persuade an audience by rhetoric rather than by telling the truth.

In Book II of The Republic, Plato describes Socrates' dialogue with his pupils. Socrates warns we should not seriously regard poetry as being capable of attaining the truth and that we who listen to poetry should be on our guard against its seductions, since the poet has no place in our idea of God.

In developing this in Book X, Plato tells of Socrates' metaphor of the three beds: one bed exists as an idea made by God (the Platonic ideal); one is made by the carpenter, in imitation of God's idea; one is made by the artist in imitation of the carpenter's.

So the artist's bed is twice removed from the truth. The copiers only touch on a small part of things as they really are, where a bed may appear differently from various points of view, looked at obliquely or directly, or differently again in a mirror. So painters or poets, though they may paint or describe a carpenter or any other maker of things, know nothing of the carpenter's (the craftsman's) art, and though the better painters or poets they are, the more faithfully their works of art will resemble the reality of the carpenter making a bed, nonetheless the imitators will still not attain the truth (of God's creation).

The poets, beginning with Homer, far from improving and educating humanity, do not possess the knowledge of craftsmen and are mere imitators who copy again and again images of virtue and rhapsodise about them, but never reach the truth in the way the superior philosophers do.

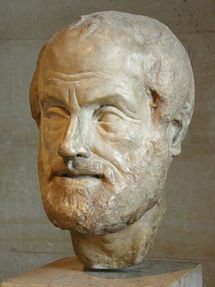

Aristotle

| Part of a series on |

| Aristotle |

|---|

|

|

Peripatetic school

physics ethics term logic view of women view of God (unmoved mover) |

|

Corpus Aristotelicum

Physics

Organon Nicomachean Ethics Politics Metaphysics On the Soul Rhetoric Poetics |

|

Ideas

Correspondence theory of truth

hexis virtue ethics (golden mean) four causes telos temporal finitism antiperistasis nature potentiality and actuality universals (substantial form) hylomorphism mimesis substances (ousia) & accidents essence category of being phronesis magnanimity sensus communis rational animal genus-differentia definition |

|

Influences & Followers

Plato

Alexander the Great Theophrastus Avicenna Averroes Maimonides St. Thomas Aquinas Alasdair MacIntyre Martha Nussbaum |

|

Related

|

Similar to Plato's writings about mimesis, Aristotle also defined mimesis as the perfection and imitation of nature. Art is not only imitation but also the use of mathematical ideas and symmetry in the search for the perfect, the timeless, and contrasting being with becoming. Nature is full of change, decay, and cycles, but art can also search for what is everlasting and the first causes of natural phenomena. Aristotle wrote about the idea of four causes in nature. The first formal cause is like a blueprint, or an immortal idea. The second cause is the material, or what a thing is made out of. The third cause is the process and the agent, in which the artist or creator makes the thing. The fourth cause is the good, or the purpose and end of a thing, known as telos.

Aristotle's Poetics is often referred to as the counterpart to this Platonic conception of poetry. Poetics is his treatise on the subject of mimesis. Aristotle was not against literature as such; he stated that human beings are mimetic beings, feeling an urge to create texts (art) that reflect and represent reality.

Aristotle considered it important that there be a certain distance between the work of art on the one hand and life on the other; we draw knowledge and consolation from tragedies only because they do not happen to us. Without this distance, tragedy could not give rise to catharsis. However, it is equally important that the text causes the audience to identify with the characters and the events in the text, and unless this identification occurs, it does not touch us as an audience. Aristotle holds that it is through simulated representation, mimesis, that we respond to the acting on the stage which is conveying to us what the characters feel, so that we may empathize with them in this way through the mimetic form of dramatic roleplay. It is the task of the dramatist to produce the tragic enactment in order to accomplish this empathy by means of what is taking place on stage.

In short, catharsis can only be achieved if we see something that is both recognizable and distant. Aristotle argued that literature is more interesting as a means of learning than history, because history deals with specific facts that have happened, and which are contingent, whereas literature, although sometimes based on history, deals with events that could have taken place or ought to have taken place.

Aristotle thought of drama as being "an imitation of an action" and of tragedy as "falling from a higher to a lower estate" and so being removed to a less ideal situation in more tragic circumstances than before. He posited the characters in tragedy as being better than the average human being, and those of comedy as being worse.

Michael Davis, a translator and commentator of Aristotle writes:

| “ | At first glance, mimesis seems to be a stylizing of reality in which the ordinary features of our world are brought into focus by a certain exaggeration, the relationship of the imitation to the object it imitates being something like the relationship of dancing to walking. Imitation always involves selecting something from the continuum of experience, thus giving boundaries to what really has no beginning or end. Mimêsis involves a framing of reality that announces that what is contained within the frame is not simply real. Thus the more "real" the imitation the more fraudulent it becomes.[2] | ” |

Contrast to diegesis

It was also Plato and Aristotle who contrasted mimesis with diegesis (Greek διήγησις). Mimesis shows, rather than tells, by means of directly represented action that is enacted. Diegesis, however, is the telling of the story by a narrator; the author narrates action indirectly and describes what is in the characters' minds and emotions. The narrator may speak as a particular character or may be the invisible narrator or even the all-knowing narrator who speaks from above in the form of commenting on the action or the characters.

In Book III of his Republic (c. 373 BCE), the ancient Greek philosopher Plato examines the style of poetry (the term includes comedy, tragedy, epic and lyric poetry):[3] All types narrate events, he argues, but by differing means. He distinguishes between narration or report (diegesis) and imitation or representation (mimesis). Tragedy and comedy, he goes on to explain, are wholly imitative types; the dithyramb is wholly narrative; and their combination is found in epic poetry. When reporting or narrating, "the poet is speaking in his own person; he never leads us to suppose that he is any one else"; when imitating, the poet produces an "assimilation of himself to another, either by the use of voice or gesture".[4] In dramatic texts, the poet never speaks directly; in narrative texts, the poet speaks as himself or herself.[5]

In his Poetics, the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle argues that kinds of poetry (the term includes drama, flute music, and lyre music for Aristotle) may be differentiated in three ways: according to their medium, according to their objects, and according to their mode or manner (section I); "For the medium being the same, and the objects the same, the poet may imitate by narration—in which case he can either take another personality as Homer does, or speak in his own person, unchanged—or he may present all his characters as living and moving before us" (section III).

Though they conceive of mimesis in quite different ways, its relation with diegesis is identical in Plato's and Aristotle's formulations; one represents, the other reports; one embodies, the other narrates; one transforms, the other indicates; one knows only a continuous present, the other looks back on a past.

In ludology, mimesis is sometimes used to refer to the self-consistency of a represented world, and the availability of in-game rationalisations for elements of the gameplay. In this context, mimesis has an associated grade: highly self-consistent worlds that provide explanations for their puzzles and game mechanics are said to display a higher degree of mimesis. This usage can be traced back to the essay "Crimes Against Mimesis."[6]

Dionysian imitatio

Three centuries after Aristotle's Poetics, from 4th century BCE to 1st century BCE, the meaning of mimesis as a literary method had shifted from "imitation of nature" to "imitation of other authors." No historical record is left to explain the reason of this change, and Dionysius' work On mimesis (On imitation) got lost; most of this work contained advice on how to identify the most suitable writers to imitate and the best way to imitate them.[7]

Latin orators and rhetoricians adopted the literary method of Dionysius' imitatio and discarded Aristotle's mimesis; the imitation literary approach is closely linked with the widespread observation that "everything has been said already," which was also stated by an Egyptian scribes around 2000 BCE. The ideal aim of this approach to literature was not originality, but to surpass the predecessor by improving their writings and set the bar to a higher level.[7]

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Mimesis, or imitation, as he referred to it, was a crucial concept for Samuel Taylor Coleridge's theory of the imagination. Coleridge begins his thoughts on imitation and poetry from Plato, Aristotle and Philip Sidney, adopting their concept of imitation of nature instead of other writers. His significant departure from the earlier thinkers lies in him arguing that art does not reveal a unity of essence through its ability to achieve sameness with nature. Coleridge claims:

[T]he composition of a poem is among the imitative arts; and that imitation, as opposed to copying, consists either in the interfusion of the SAME throughout the radically DIFFERENT, or the different throughout a base radically the same.[8]

Here, Coleridge opposes imitation to copying, the latter referring to William Wordsworth's notion that poetry should duplicate nature by capturing actual speech. Coleridge instead argues that the unity of essence is revealed precisely through different materialities and media. Imitation, therefore, reveals the sameness of processes in nature.

Luce Irigaray

The French feminist Luce Irigaray used the term to describe a form of resistance where women imperfectly imitate stereotypes about themselves so as to show up these stereotypes and undermine them.[9] This strategy is also known as strategic essentialism.

Michael Taussig

In Mimesis and Alterity (1993), the anthropologist Michael Taussig examines the way that people from one culture adopt another's nature and culture (the process of mimesis) at the same time as distancing themselves from it (the process of alterity). He describes how a legendary tribe, the "white Indians", or Cuna, have adopted in various representations figures and images reminiscent of the white people they encountered in the past (without acknowledging doing so).

Taussig, however, criticises anthropology for reducing yet another culture, that of the Cuna, for having been so impressed by their exotic (and superior) technologies of the whites, that they raised them to the status of Gods. To Taussig, this reductionism is suspect, and he argues thus from both sides in his Mimesis and Alterity to see values in the anthropologists' perspective, at the same time as defending the independence of a lived culture from anthropological reductionism. (Taussig 1993:47,48)

See also

- Life imitating art

Notes

- ↑ Gebauer and Wulf (1992, 1).

- ↑ Davis (1993, 3).

- ↑ An etext of Plato's Republic is available from Project Gutenberg. The most relevant section is the following: "You are aware, I suppose, that all mythology and poetry is a narration of events, either past, present, or to come? / Certainly, he replied. / And narration may be either simple narration, or imitation, or a union of the two? / [...] / And this assimilation of himself to another, either by the use of voice or gesture, is the imitation of the person whose character he assumes? / Of course. / Then in this case the narrative of the poet may be said to proceed by way of imitation? / Very true. / Or, if the poet everywhere appears and never conceals himself, then again the imitation is dropped, and his poetry becomes simple narration."(Plato, Republic, Book III.)

- ↑ Plato, Republic, Book III.

- ↑ See also Pfister (1977, 2-3) and Elam: "classical narrative is always oriented towards an explicit there and then, towards an imaginary 'elsewhere' set in the past and which has to be evoked for the reader through predication and description. Dramatic worlds, on the other hand, are presented to the spectator as 'hypothetically actual' constructs, since they are 'seen' in progress 'here and now' without narratorial mediation. [...] This is not merely a technical distinction but constitutes, rather, one of the cardinal principles of a poetics of the drama as opposed to one of narrative fiction. The distinction is, indeed, implicit in Aristotle's differentiation of representational modes, namely diegesis (narrative description) versus mimesis (direct imitation)" (1980, 110-111).

- ↑ Giner-Sorolla, Roger (4 2006). "Crimes Against Mimesis". Archived from the original on 2005-06-19. http://web.archive.org/web/20050619081931/http://www.geocities.com/aetus_kane/writing/cam.html. Retrieved 2006-12-17. This is a reformatted version of a set of articles originally posted to Usenet: Giner-Sorolla, Roger (2006-04-11). "Crimes Against Mimesis, Part 1". http://groups.google.com/group/rec.arts.int-fiction/msg/a11e304d16463816?dmode=source. Retrieved 2006-12-17. Giner-Sorolla, Roger (2006-04-18). "Crimes Against Mimesis, Part 2". http://groups.google.com/group/rec.arts.int-fiction/msg/6ac868aff97a3afb?dmode=source. Retrieved 2006-12-17. Giner-Sorolla, Roger (2006-04-25). "Crimes Against Mimesis, Part 3". http://groups.google.com/group/rec.arts.int-fiction/msg/66f04d5ba816f0fa?dmode=source. Retrieved 2006-12-17. Giner-Sorolla, Roger (2006-04-29). "Crimes Against Mimesis, Part 4". http://groups.google.com/group/rec.arts.int-fiction/msg/f21986cae9320282?dmode=source. Retrieved 2006-12-17.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Ruthven, K. K. (1979) Critical assumptions pp.103-4

- ↑ Coleridge, S.T. (1983) Biographia Literaria. v.1 eds. James Engell and W. Jackson Bate. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP. ISBN 0-691-09874-3. pg. 72

- ↑ See [1].

References

- Auerbach, Erich. 1953. Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature. Princeton: Princeton UP. ISBN 069111336X.

- Coleridge, S.T. 1983. Biographia Literaria. v.1 eds. James Engell and W. Jackson Bate. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP. ISBN 0-691-09874-3.

- Davis, Michael. 1999. The Poetry of Philosophy: On Aristotle's Poetics. South Bend, Indiana: St Augustine's P. ISBN 1890318620.

- Elam, Keir. 1980. The Semiotics of Theatre and Drama. New Accents Ser. London and New York: Methuen. ISBN 0416720609.

- Gebauer, Gunter, and Christoph Wulf. 1992. Mimesis: Culture—Art—Society. Trans. Don Reneau. Berkeley and London: U of California P, 1995. ISBN 0520084594.

- Kaufmann, Walter. 1992. Tragedy and Philosophy. Princeton: Princeton UP. ISBN 0691020051.

- Pfister, Manfred. 1977. The Theory and Analysis of Drama. Trans. John Halliday. European Studies in English Literature Ser. Cambridige: Cambridge UP, 1988. ISBN 052142383X.

- Tatarkiewicz, Władysław. 1980. A History of Six Ideas: An Essay in Aesthetics. Trans. Christopher Kasparek. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. ISBN 9024722330.

- Taussig, Michael. 1993. Mimesis and Alterity: A Particular History of the Senses. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415906865.

External links

- Plato's Republic II, transl. Benjamin Jowell

- Plato's Republic X, transl. Benjamin Jowell

- INFINITE REGRESS OF FORMS Plato's recounting of the "bedness" theory involved in the bed metaphor

- The University of Chicago, Theories of Media Keywords

- University of Barcelona Mimesi (Research on Poetics & Rhetorics in Catalan Literature)

- "Mimesis", an article by Władysław Tatarkiewicz for the Dictionary of History of Ideas

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||