Metamaterial

Metamaterials are artificial materials engineered to provide properties which may not be readily available in nature. These materials usually gain their properties from structure rather than composition, using the inclusion of small inhomogeneities to enact effective macroscopic behavior.[1][2][3]

The primary research in metamaterials investigates materials with negative refractive index.[4][5][6] Negative refractive index materials appear to permit the creation of superlenses which can have a spatial resolution below that of the wavelength. In other work, a form of 'invisibility' has been demonstrated at least over a narrow wave band with gradient-index materials. Although the first metamaterials were electromagnetic,[4] acoustic and seismic metamaterials are also areas of active research.[7][8]

Potential applications of metamaterials are diverse and include remote aerospace applications, sensor detection and infrastructure monitoring, smart solar power management, public safety, radomes, high-frequency battlefield communication and lenses for high-gain antennas, improving ultrasonic sensors, and even shielding structures from earthquakes.[8][9][10][11][12]

The research in metamaterials is interdisciplinary and involves such fields as electrical engineering, electromagnetics, solid state physics, microwave and antennae engineering, optoelectronics, classic optics, material sciences, semiconductor engineering, nanoscience and others.[2]

Electromagnetic metamaterials

Metamaterials have become a new subdiscipline within physics and electromagnetism (especially optics and photonics).[13][14]

They show promise for optical and microwave applications such as new types of beam steerers, modulators, band-pass filters, lenses, microwave couplers, and antenna radomes. Metamaterials consist of periodic structures.[3][4]

An electromagnetic metamaterial affects electromagnetic waves by having structural features smaller than the wavelength of light. In addition, if a metamaterial is to behave as a homogeneous material accurately described by an effective refractive index, its features must be much smaller than the wavelength. To date, subwavelength structures have shown only a few questionable results at visible wavelengths.

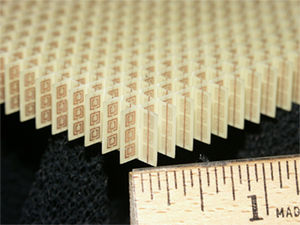

For microwave radiation, the structures need only be on the order of few centimeters. Microwave frequency metamaterials are usually synthetic, constructed as arrays of electrically conductive elements (such as loops of wire) which have suitable inductive and capacitive characteristics. These are known as split-ring resonators.[3][4]

Another structure which can exhibit subwavelength characteristics are frequency selective surfaces (FSS) known as Artificial Magnetic Conductors (AMC) or alternately called High Impedance Surfaces (HIS). These also have inductive and capacitive characteristics, which are directly related to its subwavelength structure.[15]

Photonic crystals and frequency-selective surfaces such as diffraction gratings, dielectric mirrors, and optical coatings do have apparent similarities to subwavelength structured metamaterials. However, these are usually considered distinct from subwavelength structures, as their features are structured for the wavelength at which they function, and thus cannot be approximated as a homogeneous material.

However, metamaterial structures such as photonic crystals are effective with the visible light spectrum. The middle of the visible spectrum has a wavelength of approximately 560 nm (for sunlight), the PC structures are generally half this size or smaller, that is <280 nm.

W. E. Kock developed materials that had similar characteristics to metamaterials in the late 1940s. Materials, which exhibited reversed physical characteristics were first described theoretically by Victor Veselago in 1967. A little over 30 years later, in the year 2000, Smith et al. reported the experimental demonstration of functioning electromagnetic metamaterials by stacking, periodically, split-ring resonators and thin wire structures. Later, a method was provided in 2002 to realize left-handed metamaterials using artificial lumped-element loaded transmission lines in microstrip technology. At microwave frequencies, the first real invisibility cloak was realized in 2006. However, only a very small object was imperfectly hidden.[16][17][18][19][20][21]

In 2007, one researcher[22] stated that for metamaterial applications to be realized, several goals must be achieved. Reducing energy loss, which is a major limiting factor, keep developing three-dimensional isotropic materials instead of planar structures, then finding ways to mass produce.[22]

Negative refractive index

The greatest potential of metamaterials is the possibility to create a structure with a negative refractive index, since this property is not found in any non-synthetic material. Almost all materials encountered in optics, such as glass or water, have positive values for both permittivity ε and permeability µ. However, many metals (such as silver and gold) have negative ε at visible wavelengths. A material having either (but not both) ε or µ negative is opaque to electromagnetic radiation (see surface plasmon for more details).

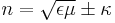

Although the optical properties of a transparent material are fully specified by the parameters ε and µ, refractive index n is often used in practice, which can be determined from  . All known non-metamaterial transparent materials possess positive ε and µ. By convention the positive square root is used for n.

. All known non-metamaterial transparent materials possess positive ε and µ. By convention the positive square root is used for n.

However, some engineered metamaterials have ε < 0 and µ < 0. Because the product εµ is positive, n is real. Under such circumstances, it is necessary to take the negative square root for n. Physicist Victor Veselago proved that such substances can transmit light.

The foregoing considerations are simplistic for actual materials, which must have complex-valued ε and µ. The real parts of both ε and µ do not have to be negative for a passive material to display negative refraction.[23] Metamaterials with negative n have numerous interesting properties:

- Snell's law (n1sinθ1 = n2sinθ2), but as n2 is negative, the rays will be refracted on the same side of the normal on entering the material.

- The Doppler shift is reversed: that is, a light source moving toward an observer appears to reduce its frequency.

- Cherenkov radiation points the other way.

- The time-averaged Poynting vector is antiparallel to phase velocity. This means that unlike a normal right-handed material, the wave fronts are moving in the opposite direction to the flow of energy.

For plane waves propagating in electromagnetic metamaterials, the electric field, magnetic field and wave vector follow a left-hand rule, thus giving rise to the name left-handed (meta)materials. It should be noted that the terms left-handed and right-handed can also arise in the study of chiral media, but their use in that context is unrelated to this effect. The effect of negative refraction is analogous to wave propagation in a left-handed transmission line, and such structures have been used to verify some of the effects described here.

Handedness is an important characteristic in metamaterial design and fabrication as it relates to the direction of wave propagation. Metamaterials as left-handed media occur when both permittivity ε and permeability µ are negative. Furthermore, left handedness occurs mathematically from the handedness of the vector triplet E, H and k.[2]

In ordinary, everyday materials - solid, liquid, or gas; transparent or opaque; conductor or insulator - right handedness dominates. This means that permittivity and permeability are both positive resulting in an ordinary positive index of refraction. However, metamaterials have the capability to exhibit a state where both permittivity and permeability are negative, resulting in an extraordinary, index of negative refraction, i.e. a left-handed material.[2][24]

Electromagnetic, acoustic and seismic metamaterials have been proposed and built.

Different classes of electromagnetic metamaterials

Electromagnetic metamaterials have the potential of an enormous impact, because with the capability to direct wave propagation at the electromagnetic level, whole systems can be refined. For example, low density of materials means that components, devices, and systems can be extremely lightweight and increasingly small, while at the same time enhancing system and component performance.[1]

Because physicists can now probe deeper into elementary particles, the border between synthetic materials and metamaterials is vague and novel properties are being discovered in natural materials. Unusual properties are also produced in conventional materials by processing them at nanoscales.[2] However, a distinguishing feature of metamaterials is that they can be specifically fabricated to fulfill a certain objective and to fit the desired application.[1][2] The size and spacing of elements in the material are created smaller than the radiated wavelength. This incident radiation, therefore distinguishes the metamaterial as homogenous.[25]

Electromagnetic metamaterials have been synthesized by embedding various constituents/inclusions with novel geometric shapes and forms in some host media.[1] Various types of composite material, both electromagnetic and other types have been and are being studied by various research groups worldwide (see all sections and references below).

Often the behavior, designed structure, and designed parameters of electromagnetic metamaterials are described in by certain terms without reference to their frequency dependence. However, in this type of composite media electromagnetic waves interact with the designed inclusions, inducing electric and magnetic moments, which in turn affect the macroscopic effective permittivity and permeability of this, bulk composite "medium".[1]

Since electromagnetic metamaterials can be synthesized by embedding artificially fabricated inclusions (as large-scale artificial atoms) in a specified host medium, or on a host surface, this provides the designer with a large set of available, independent parameters. Those parameters define how the metamaterial is to be engineered. They include the properties of the host materials, and the size shape and composition of the inclusions. Other parameters to consider are the density, arrangement, and alignment of these inclusions. By defining all these parameters during fabrication, a metamaterial is engineered for specific electromagnetic response functions. Additionally, these response functions are not found in the individual constituents. All these design parameters can play a key role in the final outcome of the synthesis process. Among these the geometry (or shape) of the inclusions is one parameter that can provide the new possibilities for processed metamaterials.[1]

In light of these developments, electromagnetic metamaterials are represented by different classes, as follows:[1][2]

Double negative metamaterials

In double negative metamaterials (DNG), both permittivity and permeability are negative resulting in a negative index of refraction. DNGs are also referred to as negative index metamaterials (NIM). Other terminologies for DNGs are "left-handed media", "media with a negative refractive index", and "backward-wave media", along with other nomenclatures.[1]

In optical materials, if both permittivity ε and permeability µ are positive this results in propagation in the forward direction. If both ε and µ are negative, a backward wave is produced. If ε and µ have different polarities, then this does not result in wave propagation. Mathematically, quadrant II and quadrant IV have coordinates (0,0) in a coordinate plane where ε is the horizontal axis, and µ is the vertical axis.[2]

In 1968 Victor Veselago published a paper theorizing plane wave propagation in a material whose permittivity and permeability were assumed to be simultaneously negative. In such a material, he showed that the phase velocity would be antiparallel to the direction of poynting vector. This is contrary to wave propagation in natural occurring materials. In the years 2000 and 2001, papers were published about the first demonstrations of an artificial material that produced a negative index of refraction. By 2007, research experiments which involved negative refractive index had been conducted by many groups.[1][12]

Studies have elucidated applications for negative refractive index materials. These applications are phase compensation with electrically small resonators, negative angles of refraction, subwavelength waveguides, backward wave antenna, Cherenkov radiation, photon tunneling, and enhanced electrically small antenna. The concept of continuous wave excitation is a key component of these studies to obtain the negative index refraction using DNG media, and then to introduce the results of research into these applications.[1] DNG metamaterials are innately dispersive, so their permittivity ε, permeability µ, and refraction index n, will alter with changes in frequency.[24] To date, DNGs have only been demonstrated as artificially constructed materials.[1]

It is worth noting that passive single negative (SNG) and double negative (DNG) metamaterials are inherently dispersive. Therefore, for passive metamaterials, the real parts of the material parameters are most often negative only over a certain band of frequencies and, thus, their values can shift, or vary, significantly with the changes in frequency. As a result, one should, in general, take into account the frequency dependence of such material parameters. Based in the original problem of a dispersive nature, but traveling a somewhat different avenue, are active metamaterials. These are intended to have the capability to exhibit negative parameters over a somewhat larger band of frequencies.[26]

Single negative metamaterials

In single negative (SNG) metamaterials either permittivity or permeability are negative, but not both. These are ENG metamaterials and MNG metamaterials discussed below. Interesting experiments have been conducted by combining two SNG layers into one metamaterial. These effectively create another form of DNG metamaterial. A slab of ENG material and slab of MNG material have been joined to conduct wave reflection experiments. This resulted in the exhibition of properties such as resonances, anomalous tunneling, transparency, and zero reflection. Like DNG metamaterials, SNGs are innately dispersive, so their permittivity ε, permeability µ, and refraction index n, will alter with changes in frequency.[24]

- Epsilon negative media (ENG) – permittivity ε is negative while permeability µ is positive.[1][24] Many plasmas exhibit this characteristic. For example noble metals such as gold or silver will exhibit this characteristic in the infrared and visible spectrums.

- Mu-negative media (MNG) – permittivity ε is positive while permeability µ is negative.[1][24] A material, which called gyrotropic or gyromagnetic exhibits this characteristic. A gyrotropic material is a medium that has been altered by the presence of a quasistatic magnetic field. This results in the magneto-optic effect. A magneto-optic effect is any one of a number of phenomena in which an electromagnetic wave propagates through a medium that has been altered by the presence of a quasistatic magnetic field. In such a material, left- and right-rotating elliptical polarizations can propagate at different speeds, leading to a number of important phenomena. When light is transmitted through a layer of magneto-optic material, the result is called the Faraday effect: the plane of polarization can be rotated, forming a Faraday rotator. The results of reflection from a magneto-optic material are known as the magneto-optic Kerr effect (not to be confused with the nonlinear Kerr effect). Two gyrotropic materials with reversed rotation directions of the two principal polarizations are called optical isomers.

Electromagnetic bandgap metamaterials

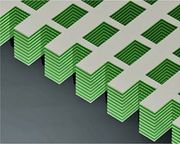

Electromagnetic bandgap metamaterials control the propagation of light. This is accomplished with either a class of metamaterial known as photonic crystals (PC), or another class known as left-handed materials (LHM) Both are a novel class of artificially engineered structure, and both control and manipulate the propagation of electromagnetic waves (light). PCs can prohibit light propagation altogether. However, both the PC and LHM are capable of allowing it to propagate in certain, designed directions, and both can be designed to have electromagnetic bandgaps at desired frequencies.[27][28]

In addition, metamaterials such as Photonic crystals (PC) are complex, periodic, materials and are considered to be electromagnetic bandgap material. However, a PC is at first distinguished from sub-wavelength structures, such as tunable metamaterials, because the PC derives its properties from its band gap characteristics. In addition the PC operates at the wavelength of light, compared to other metamaterials which operate as a sub-wavelength structure. Furthermore, the complex response of photonic crystals functions by diffracting light. In contrast, a permittivity and permeability defines metamaterials (also a complex response), which is derived from their sub-wavelength structure and diffraction must be eliminated.[29]

The PC is also a material in which periodic inclusions inhibit wave propagation due to destructive interference from scattering from the periodic repetition. The photonic bandgap property of PCs makes them the EM analog of the electronic semi-conductor crystals.[30]

Intended material fabrication of EBGs has the goal of creating periodic, dielectric structures, with low loss, and that are of high quality. An EBG affects the properties of the photon in the same way semiconductor materials affect the properties of the electron. So, it happens that the PC is the perfect bandgap material, because it allows no propagation of light.[31] Each unit of the prescribed periodic structure acts like large scale atoms.[1][31]

Electromagnetic bandgap structured (EBG) metamaterials are designed to prevent the propagation of an allocated bandwidth of frequencies, for certain arrival angles and polarizations. With EBG materials new methods utilize the properties of various dielectrics to achieve better performance. A variety of geometries and structures have been proposed to fabricate the special EBG metamaterial properties. However, in practice it is impossible to build a flawless EBG device. Factors such as advances in ideas, research, testing and development, along with the prospects of significant technological solutions, have driven the development of EBG applied science.[1][2]

Commercial production of dielectric EBG devices has lagged, because commercial rewards are not readily apparent. However, start-up companies are cropping up solely focused on exploiting EBG metamaterials. These metamaterials have been manufactured for frequencies ranging from a few gigahertz (GHz) up to several terahertz (THz). In other words, applications have achieved fabricated media for radio frequency, microwave and mid-infrared regions. "It now appears that EBG concepts can, in many cases act as improved replacements for conventional solutions to electromagnetic problems."[1] Applicable developments include an EBG transmission line, fabricated utilizing the special properties of metamaterials, EBG woodpiles made of square dielectric bars, and several different types of low gain antennas.[1][2]

An EBG is a result of a metamaterial that functions in the regime where the period is an appreciable amount of the wavelength, and constructive and destructive interference occur.

Double positive medium

Double positive mediums (DPS) do occur in nature such as naturally occurring dielectrics. Permittivity and magnetic permeability are both positive and wave propagation is in the forward direction. Artificial materials have been fabricated which have DPS, ENG, and MNG properties combined.[1]

Bi-isotropic and bianisotropic metamaterials

Categorizing metamaterials into double or single negative, or double positive, is normally done based on the assumption that the metamaterial has independent electric and magnetic responses described by the parameters ε and µ. However in many examples of electromagnetic metamaterials, the electric field causes magnetic polarization, and the magnetic field induces an electrical polarization, i.e., magnetoelectric coupling. Such media are denoted as being bi-isotropic. Media which are exhibit magneto-electric coupling, and which are also anisotropic (which is the case for many commonly used metamaterial structures[32]), are referred to as bi-anisotropic.[33][34] are denoted as bi-anisotropic.

Intrinsic to magnetoelectric coupling of bi-isotropic media, are four material parameters interacting with the electric (E) and magnetic (H) field strengths, and electric (D) and magnetic (B) flux densities. These four material parameters are ε, µ, κ and χ or permittivity, permeability, strength of chirality, and the Tellegen parameter respectively. Furthermore, in this type of media, the material parameters do not vary with changes along a rotated coordinate system of measurements. In this way they are also defined as invariant or scalar.[2]

The intrinsic magnetoelectric parameters, κ and χ, affect the phase of the wave. Furthermore, the effect of the chirality parameter is to split the refractive index. In isotropic media this results in wave propagation only if ε and µ have the same sign. In bi-isotropic media with χ assumed to be zero, and κ a non-zero value, different results are shown. Both a backward wave and a forward wave can occur. Alternatively, two forward waves or two backward waves can occur, depending on the strength of the chirality parameter.

Chiral metamaterials

When a metamaterial is constructed from chiral elements then it is considered to be a chiral metamaterial, and the effective parameter k will be non-zero. This is a potential source of confusion as within the metamaterial literature there are two conflicting uses of the terms left and right-handed. The first refers to one of the two circularly polarized waves which are the propagating modes in chiral media. The second relates to the triplet of electric field, magnetic field and Poynting vector which arise in negative refractive index media, which in most cases are not chiral.

Some of the earliest structures which may be considered metamaterials date back to Jagadish Chandra Bose who in 1898 researched substances with chiral properties and to studies by Karl Ferdinand Lindman on wave interaction with metallic helices as artificial chiral media in the early twentieth century. In the 1950s and 1960s, artificial dielectrics were studied for lightweight microwave antennas. Microwave radar absorbers moved into the research arena in the 1980s and 1990s as applications for artificial chiral media.[2]

Wave propagation properties in chiral metamaterials demonstrate that negative refraction can be realized in chiral metamaterials with a strong chirality, with neither negative ε nor μ as a requirement.[35] [36]. This is because the refractive index of the medium has distinct values for the left and right, given by

It can be seen that a negative index will occur for one polarization if κ > √εµ. In this case, it is not necessary that either or both ε and µ be negative for backward wave propagation.[2]

Split-ring resonators

A split-ring resonator (SRR) is a component part of a negative index metamaterial (NIM), also known as double negative metamaterials (DNG). They are also component parts of other types of metamaterial such as Single Negative metamaterial (SNG). SRR's are also used for research in Terahertz metamaterials, Acoustic metamaterials, and Metamaterial antennas. SRRs are a pair of concentric annular rings with splits in them at opposite ends. The rings are made of nonmagnetic metal like copper and have small gap between them.

A magnetic flux penetrating the metal rings will induce rotating currents in the rings, which produce their own flux to enhance or oppose the incident field (depending on the SRR's resonant properties). This field pattern is dipolar. Because of splits in the rings, the structure can support resonant wavelengths much larger than the diameter of the rings. This would not happen in closed rings. The small gaps between the rings produces large capacitance values which lower the resonating frequency, as the time constant is large. The dimensions of the structure are small compared to the resonant wavelength. This results in low radiative losses, and very high quality factors.

At frequencies below the resonant frequency, the real part of the magnetic permeability of the SRR becomes large (positive), and at frequencies higher than resonance it will become negative. This negative permeability can be used with the negative dielectric constant of another structure to produce negative refractive index materials.

Main articles

Next this article lists most of the available metamaterial types which are being researched. These are linked to the main articles, which describe each type in more detail.

Terahertz metamaterials

Terahertz radiation lies at the far end of the infrared band, just before the start of the microwave band.

Terahertz metamaterials are metamaterials which interact at terahertz frequencies. For research or applications of the terahertz range for metamaterials and other materials, the frequency range is usually defined as 0.1 to 10 THz. This corresponds to the millimeter and submillimeter wavelengths between 3 mm (EHF band) and 0.03 mm (long-wavelength edge of far-infrared light).

Photonic metamaterials

A Photonic metamaterial is an artificially fabricated, sub-wavelength, periodic structure, designed to interact with optical frequencies (mid-infrared). The sub-wavelength period distinguishes the photonic metamaterial from photonic band gap structures.[39][40]

Tunable metamaterials

A tunable metamaterial is a metamaterial which has the capability to arbitrarily adjust frequency changes in the refractive index at will. A tunable metamaterial encompasses the development of expanding beyond the bandwidth limitations in left-handed materials by constructing various types of metamaterials.

Frequency selective surface (FSS) based metamaterials

Link to section: FSS based metamaterials

FSS based metamaterials have become an alternative to the fixed frequency metamaterial. The former allow for optional changes of frequencies in a single medium (metamaterial), rather than the restrictive limitations of a fixed frequency response. Other applications are also being explored.[41]

Nonlinear metamaterials

Metamaterials may also be fabricated which include some form of nonlinear media - materials which have properties which change with the power of the incident wave. Nonlinear media are essential for nonlinear optics. However most optical materials have a relatively weak nonlinear response, meaning that their properties only change by a small amount for large changes in the intensity of the electromagnetic field. Nonlinear metamaterials can overcome this limitation, since the local electromagnetic fields of the inclusions in the metamaterial can be much larger than the average value of the field. In addition, exotic properties such as a negative refractive index, open up opportunities to tailor the phase matching conditions, which must be satisfied in any nonlinear optical structure.

Metamaterial absorber

A metamaterial absorber manipulates the loss components of the complex effective parameters, permittivity and magnetic permeability of metamaterials, to create a high electromagnetic absorber. Loss components are often noted in applications of negative refractive index (photonic metamaterials, antenna systems metamaterials) or transformation optics (metamaterial cloaking, celestial mechanics), but often not utilized in these applications.

Applications of metamaterials

Several applications of metamaterials have been proposed in the literature, some of which have also been realized experimentally.

Superlens

A superlens uses metamaterials to achieve resolution beyond the diffraction limit. The diffraction limit is inherent in conventional optical devices or lenses.[42][43]

It was first postulated by John Pendry[44] and colleagues in Physical Review Letters that a negative refractive material would enable a superlens because of two properties:

- A wave propagating in a negative-refractive medium exhibits a phase advance instead of a phase delay in conventional materials;

- Evanescent waves in a negative-refractive medium increase in amplitude as they move away from their origin.

However, it was demonstrated via simple geometrical arguments that in order to enable property #1 above, negative time must be enforced. Furthermore, if property #2 is actually possible, this would lead to infinite energy creation at infinite distances. Both properties thus appear to yield non-causal behaviors.[45]

The first superlens with a negative refractive index provided resolution three times better than the diffraction limit and was demonstrated at microwave frequencies.[46] Subsequently, the first optical superlens (an optical lens which exceeds the diffraction limit) was created and demonstrated,[47] but the lens did not rely on negative refraction. Instead, a thin silver film was used to enhance the evanescent modes through surface plasmon coupling.

Two developments in superlens research were reported in 2008.[48] In the first case, alternate layers of silver and magnesium fluoride were deposited on a substrate. Then nanoscale grids were cut into the layers, which resulted in a 3-dimensional composite structure with a negative refractive index in the near-infrared region.[28] In the second case, a metamaterial was formed from silver nanowires which were electrochemically deposited in porous aluminium oxide. The material exhibited negative refraction.[49]. In early 2007, a metamaterial with a negative index of refraction for a light wavelength just outside the frequency of the color red was announced. The material had an index of −0.6 at 780 nm.[50]

Cloaking devices

Metamaterials are a basis for attempting to build a practical cloaking device. The possibility of a working invisibility cloak was demonstrated on October 19, 2006. According to the article, a team led by scientists at Pratt School of Engineering, Duke University has demonstrated the first working "invisibility cloak." The cloak deflects microwave beams so they flow around a "hidden" object inside with little distortion, making it appear almost as if nothing were there at all. Such a device typically involves surrounding the object to be cloaked with a shell which affects the passage of light near it.[51] The associated report was published in the journal Science.[52]

In related research, it may eventually be possible to use plasmons to cancel out visible light or electromagnetic radiation emanating from an object. This plasmonic cover would work by suppressing the scattering of light by resonating with illuminated light, which could render objects "nearly invisible to an observer." The plasmonic screen would have to be tuned to the object being hidden, and would only suppress a specific wavelength—an object made invisible in red light would still be visible in multicolored daylight.[53]

In October 2006, a US-British team of scientists created a metamaterial which rendered an object invisible to microwave radiation.[54] As the visible spectrum is one of the bands of electromagnetic radiation, this was considered the first step toward a cloaking device for visible light, although more advanced nanoengineering techniques would be needed due to light's short wavelengths.

On 2 April 2007, Vladimir Shalaev at Purdue University announced a theoretical design for an optical cloaking device based on the 2006 British concept. The design deploys an array of tiny needles projecting from a central spoke that would render an object within the cloak invisible for red light (wavelength of 632.8 nanometers).[55]

In 2009, at Duke University the latest advance—a series of algorithms were developed, to guide the design and fabrication of new metamaterials. David Smith of the Duke Engineering department, comparing the 2006 device, is quoted: "The difference between the original device and the latest model is like night and day. The new device can cloak a much wider spectrum of waves—nearly limitless—and will scale far more easily to infrared and visible light. The approach we used should help us expand and improve our abilities to cloak different types of waves." The article also noted that "once the algorithm was developed, the latest cloaking device was completed from conception to fabrication in nine days, compared to the four months required to create the original, and more rudimentary, device."[56]

Metamaterial antennas

Metamaterial antennas are a class of antennas which use metamaterials to improve the performance of the antenna systems.[12][57][58] Applying metamaterials to increase performance of antennas has garnered much interest.[12] Demonstrations have shown that metamaterials could enhance the radiated power of an antenna.[12][59] Materials which can attain negative permeability could possibly allow for properties such as an electrically small antenna size, high directivity, and tunable operational frequency.[12]

Acoustic metamaterials

| Continuum mechanics | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

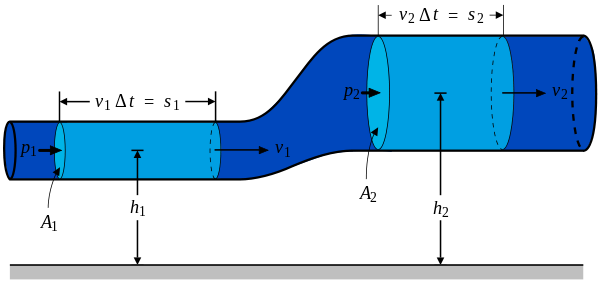

Acoustic metamaterials are artificially fabricated materials designed to control, direct, and manipulate sound in the form of sonic, infrasonic, or ultrasonic waves, as these might occur in gases, liquids, and solids. The hereditary line into acoustic metamaterials follows from theory and research in electromagnetic metamaterials. Furthermore, with acoustic metamaterials, sonic waves can now be extended to the negative refraction domain.[7]

Seismic metamaterials

Seismic metamaterials, are metamaterials which are designed to counteract the adverse effects of seismic waves on man-made structures, which exist on or near the surface of the earth.[8][60][61]

Other uses

Metamaterials have been proposed for designing agile antennas.[62] Research at the National Institute of Standards and Technology has demonstrated that thin metamaterial films can greatly reduce the size of resonating circuits that generate microwaves, potentially enabling even smaller cell phones and other microwave devices.[63] It has been theorized that metamaterials could be built to bend matter around them because of the subatomic properties of matter. Such a matter cloak could for example bend a bullet around a person rather than absorb the impact as traditional bulletproof vests do.[64]

Theoretical models

Left-handed materials were first described theoretically by Victor Veselago in 1967.[18]

John Pendry was the first to theorize a practical way to make a left-handed metamaterial. Left-handed in this context means a material in which the right-hand rule is not followed, allowing an electromagnetic wave to convey energy (have a group velocity) in the lode against its phase velocity. Pendry's initial idea was that metallic wires aligned along the direction of propagation could provide a metamaterial with negative permittivity (ε < 0). Note however that natural materials (such as ferroelectrics) were already known to exist with negative permittivity; the challenge was to construct a material which also showed negative permeability (µ < 0). In 1999 Pendry demonstrated that a split ring (C shape) with its axis placed along the direction of wave propagation could provide a negative permeability. In the same paper, he showed that a periodic array of wires and ring could give rise to a negative refractive index. A related negative-permeability particle, which was also proposed by Pendry, is the Swiss roll.

The analogy is as follows: All materials are made of atoms, which are dipoles. These dipoles modify the light velocity by a factor n (the refractive index). The ring and wire units play the role of atomic dipoles: the wire acts as a ferroelectric atom, while the ring acts as an inductor L and the open section as a capacitor C. The ring as a whole therefore acts as an LC circuit. When the electromagnetic field passes through the ring, an induced current is created and the generated field is perpendicular to the magnetic field of the light. The magnetic resonance results in a negative permeability; the index is negative as well. (The lens is not truly flat, since the capacitance of the structure imposes a slope for the electric induction.)

In peer reviewed journal articles (see References), there are several (mathematical) material models which describe frequency response in DNGs.[1] One of these is the Lorentz model. This describes electron motion in terms of a driven-damped, harmonic oscillator. When the acceleration component of the Lorentz mathematical model is small compared to the other components of the equation, then the Debye model is applied. When the restoring force component is negligible, and the coupling coefficient is generally the plasma frequency, then the Drude model is applied. There are other component distinctions that call for the use of one of these models, depending on its polarity, or purpose.[1]

Institutional networks engaged in metamaterial research

Novel electromagnetic materials

The number of groups studying metamaterials is continuously increasing. For example, Duke University has initiated an umbrella organization researching metamaterials under the banner "Novel Electromagnetic Materials" and became a leading metamaterials research center. The center is a part of an international team, which also includes California Institute of Technology, Harvard University, UCLA, Max Planck Institute of Germany, and the FOM Institute of the Netherlands. In addition, there are currently six groups connected to this umbrella organization, which are conducting intense metamaterial research:[9]

MURI

MURI stands for Multidisciplinary University Research Initiative. Tens of Universities and a few government organizations participate in the MURI program. A MURI Metamaterials web page can be found at UC Berkeley. A few other Universities which participate in MURI are UC Los Angeles, UC San Diego, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Imperial College in London, UK. The sponsors are Office of Naval Research (ONR) and the Defense Advanced Research Project Agency (DARPA).[65]

The MURI program supports research by teams of research investigators that intersect more than one traditional science and engineering discipline in order to accelerate both research progress and transition of research results to application. Most MURI efforts involve researchers from multiple academic institutions and academic departments. Based on the proposals selected in the fiscal 2009, a total of 69 academic institutions are expected to participate in 41 research efforts.[66]

Metamorphose

The Virtual Institute for Artificial Electromagnetic Materials and Metamaterials ”Metamorphose VI AISBL” is a non-for-profit international association whose purposes are the research, the study and the promotion of artificial electromagnetic materials and metamaterials. Some of their stated main tasks are to spread excellence in this field, in particular, by organizing scientific conferences and creating specialized journals in this field; create and manage research programs in this field; activate and manage training programs (including PhD and training programs for students and industrial partners); and transfer new technology in this field to the European Industry.[67][68]

See also

- Fresnel lens

- List of emerging technologies

- Litz wire is a 3D structure designed to reduce skin effect

- METATOY, an acronym for metamaterial for rays

- Negative refraction

- Phonon is a quantized mode of vibration occurring in a rigid crystal lattice.

- Scattering Matrix Method

- Surface phonon

- Zone plate

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 Engheta, Nader; Richard W. Ziolkowski (2006-06). [The book online here Metamaterials: Physics and Engineering Explorations]. Wiley & Sons. pp. xv, 3–30, 37, 143–150, 215–234, 240–256. ISBN 9780471761020. The book online here.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 Zouhdi, Saïd; Ari Sihvola, Alexey P. Vinogradov (2008-12). Metamaterials and Plasmonics: Fundamentals, Modelling, Applications. New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 3–10, Chap. 3, 106. ISBN 9781402094064. http://books.google.com/books?id=OqRi4s_EskoC&pg=PA6.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Smith, David R. (2006-06-10). "What are Electromagnetic Metamaterials?". Novel Electromagnetic Materials. The research group of D.R. Smith. http://people.ee.duke.edu/~drsmith/about_metamaterials.html. Retrieved 2009-08-19.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Shelby, RA; Smith, DR; Schultz, S; Smith D.R; Shultz S. (2001). "Experimental Verification of a Negative Index of Refraction". Science (journal) 292 (5514): 77. doi:10.1126/science.1058847. PMID 11292865.

- ↑ Pendry, John B. (2004). "Negative Refraction". Contemporary Physics (Princeton University Press) 45 (3): 191–202. doi:10.1080/00107510410001667434. ISBN 0691123470. http://www.cmth.ph.ic.ac.uk/photonics/Newphotonics/pdf/NegRef_submit.pdf. Retrieved 2009-08-26.

- ↑ Veselago, V. G. (1968). "The electrodynamics of substances with simultaneously negative values of [permittivity] and [permeability]". Soviet Physics Uspekhi 10 (4): 509–514. doi:10.1070/PU1968v010n04ABEH003699.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 . Guenneau, Sébastien; Alexander Movchan, Gunnar Pétursson, and S. Anantha Ramakrishna (2007). "Acoustic metamaterials for sound focusing and confinement" (free download pdf). New Journal of Physics 9 (399): 1367–2630. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/9/11/399.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Brun, M.; S. Guenneau, and A.B. Movchan (2009-02-09). "Achieving control of in-plane elastic waves". Appl. Phys. Lett. 94 (061903): 1–7. doi:10.1063/1.3068491+accessdate+=2009-09-09 (inactive 2010-03-17). http://arxiv.org/PS_cache/arxiv/pdf/0812/0812.0912v1.pdf.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Smith, David R; Research group (2005-01-16). "Novel Electromagnetic Materials program". http://people.ee.duke.edu/~drsmith/collaborators.htm. Retrieved 2009-08-17.

- ↑ Rainsford, Tamath J.; Samuel P. Mickan, and Derek Abbott (9 March 2005). "T-ray sensing applications: review of global developments". Proc. SPIE (Conference Location: Sydney, Australia 2004-12-13: The International Society for Optical Engineering) 5649 Smart Structures, Devices, and Systems II (Poster session): 826–838. doi:10.1117/12.607746.

- ↑ Cotton, Micheal G. (2003-12). "Applied Electromagnetics". 2003 Technical Progress Report (NITA – ITS) (Boulder, CO, USA: NITA – Institute for Telecommunication Sciences) Telecommunications Theory (3): 4–5. http://www.its.bldrdoc.gov/pub/ntia-rpt/tpr/2003/telecommunications_theory-03.pdf. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 Alici, Kamil Boratay; Özbay, Ekmel (2007). "Radiation properties of a split ring resonator and monopole composite". Physica status solidi (b) 244: 1192. doi:10.1002/pssb.200674505.

- ↑ Hapgood, Fred; Grant, Andrew (From the April 2009 issue; published online 2009-03-10). "Metamaterial Revolution: The New Science of Making Anything Disappear" (Magazine article access for free. Four page article.). Discover Magazine: p. page 2. http://discovermagazine.com/2009/apr/10-metamaterial-revolution-new-science-making-anything-disappear. Retrieved 2010-03-04.

- ↑ McDonald, Kim (2000-03-21). "UCSD Physicists Develop a New Class of Composite Material with 'Reverse' Physical Properties Never Before Seen". UCSD Science and Engineering. http://ucsdnews.ucsd.edu/newsrel/science/mccomposite.htm. Retrieved 2010-12-17.

- ↑ Sievenpiper, Dan et al.; Lijun Zhang; Broas, R.F.J.; Alexopolous, N.G.; Yablonovitch, E. (1999-11). "High-Impedance Electromagnetic Surfaces with a Forbidden Frequency Band" (Free PDF download. Cited by 1,078). IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques 47 (11): 2059. doi:10.1109/22.798001. http://www.rsl.ku.edu/~eecs501/Hi-Z_surfaces/Sievenpiper1999TMTTpp2059-2074.pdf. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- ↑ Kock, W. E. (1946). "Metal-Lens Antennas". IRE Proc. 34: 828.

- ↑ Kock, W.E. (1948). "Metallic Delay Lenses". Bell. Sys. Tech. Jour. 27: 58–82.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Veselago, V. G. (1968 (Russian text 1967)). "The electrodynamics of substances with simultaneously negative values of ε and μ". Sov. Phys. Usp. 10 (4): 509–14. doi:10.1070/PU1968v010n04ABEH003699. http://ufn.ru/en/articles/1968/4/a/.

- ↑ Caloz, C.; Chang, C.-C. and Itoh, T. (2001). "Full-wave verification of the fundamental properties of left-handed materials in waveguide configurations". J. Appl. Phys. 90: 11. doi:10.1063/1.1408261. http://xlab.me.berkeley.edu/MURI/publications/publications_9.pdf.

- ↑ Eleftheriades, G.V.; Iyer A.K.; and Kremer, P.C. (2002). "Planar Negative Refractive Index Media Using Periodically L-C Loaded Transmission Lines". IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques 50: 2702–2712. doi:10.1109/TMTT.2002.805197.

- ↑ Caloz, C. and Itoh, T. (2002). "Application of the Transmission Line Theory of Left-handed (LH) Materials to the Realization of a Microstrip 'LH line'". IEEE Antennas and Propagation Society International Symposium 2: 412. doi:10.1109/APS.2002.1016111.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 DOE / Ames Laboratory (2007-01-04). "Metamaterials found to work for visible light" (Costas Soukoulis discusses some metamaterials). HTML. http://eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2007-01/dl-mft010407.php?light. Retrieved 2009-11-07.

- ↑ R. A. Depine and A. Lakhtakia (2004). "A new condition to identify isotropic dielectric-magnetic materials displaying negative phase velocity". Microwave and Optical Technology Letters 41: 315. doi:10.1002/mop.20127.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 Eleftheriades, George V.; Keith G. Balmain (2005). Negative-refraction metamaterials: fundamental principles and applications. Wiley, John & Sons. p. 340. ISBN 9780471601463. http://books.google.com/books?id=a4MiyF5_N7MC&pg=PA379.

- ↑ Pendry, John B.; and David R. Smith (2004-06). "Reversing Light: Negative Refraction". Physics Today (American Institute of Physics) 57 (June 37): 2 of 9 (originally page 38 of pp. 37–45). http://esperia.iesl.forth.gr/~ppm/DALHM/publications/papers/PhysicsTodayv57p37.pdf. Retrieved 2009-09-27.

- ↑ Alù, Andrea and; Nader Engheta (2004-01). "Guided Modes in a Waveguide Filled With a Pair of Single-Negative (SNG), Double-Negative (DNG), and/or Double-Positive (DPS) Layers" (Free PDF download. Cited by 123). IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques 52 (01): 199. doi:0.1109/TMTT.2003.821274 (inactive 2010-03-17). http://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1001&context=ese_papers. Retrieved 2010-01-03.

- ↑ Engheta, Nader; Richard W. Ziolkowski (2006-06) (added this reference on 2009-12-14.). Metamaterials: physics and engineering explorations. Wiley & Sons. pp. 211–221. ISBN 9780471761020. http://books.google.com/books?id=51e0UkEuBP4C.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Valentine, J; Zhang, S; Zentgraf, T; Ulin-Avila, E; Genov, DA; Bartal, G; Zhang, X (2008). "Three-dimensional optical metamaterial with a negative refractive index". Nature 455 (7211): 376–9. doi:10.1038/nature07247. PMID 18690249.

- ↑ Pendry, JB (2009-04-11). "Metamaterials Generate Novel Electromagnetic Properties" (This is a seminar - lecture series lasting one semster - fall 2009.). UC Berkeley Atomic Physics Seminar 290F Main. http://ultracold.physics.berkeley.edu/seminar/pmwiki/Main/MetamaterialsGenerateNovelElectromagneticProperties. Retrieved 2009-12-14.

- ↑ Chappell, William leads the IDEA laboratory at Purdue University (2005). "Metamaterials". reasearch in various technologies. https://engineering.purdue.edu/IDEAS/Metamaterials.html. Retrieved 2009-11-23.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Edited by Soukoulis, C. M. (2001-05). Photonic Crystals and Light Localization in the 21st Century (Proceedings of the NATO Advanced Study Institute on Photonic Crytals and Light Localization, Crete, Greece, June 18–30, 2000 ed.). London: Springer London, Limited. pp. xi. ISBN 9780792369486 and 0792369483. http://books.google.com/books?id=y8O7cfQl9ogC&pg=PP1&dq=photonic+crystals+and+light+localization+in+the+21st+century#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- ↑ Marques, Ricardo; Medina, Francisco; Rafii-El-Idrissi, Rachid (2002-04-04). "Role of bianisotropy in negative permeability and left-handed metamaterials" (Free PDF download of this article is linked to this reference.). Physical Review B 65: 144440–1. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.65.144440. http://centro.us.es/gmicronda/Miembros/Ricardo/1-Role-of-bianisotropy.pdf. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ Rill, M. S. et al.; Kriegler, CE; Thiel, M; Von Freymann, G; Linden, S; Wegener, M (2008-12-22). "Negative-index bianisotropic photonic metamaterial fabricated by direct laser writing and silver shadow evaporation". Optics Letters 34 (1): 19–21. doi:10.1364/OL.34.000019. PMID 19109626. http://www.opticsinfobase.org/ol/abstract.cfm?uri=ol-34-1-19.

- ↑ Kriegler, C. E. et al.; Rill, Michael Stefan; Linden, Stefan; Wegener, Martin (submitted 2009-03-31 to be published 2010-04). "Bianisotropic photonic metamaterials" (download free PDF article.). IEEE journal of selected topics in quantum electronics 999: 1–15. doi:10.1109/JSTQE.2009.2020809. http://esperia.iesl.forth.gr/~ppm/PHOME/publications/IEEE_10_1109_2009.pdf. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ Wang, Bingnan et al; Zhou, Jiangfeng; Koschny, Thomas; Kafesaki, Maria; Soukoulis, Costas M (2009-11). "Chiral metamaterials: simulations and experiments". J. Opt. A: Pure Appl. Opt. 11: 114003 (10pp). doi:10.1088/1464-4258/11/11/114003. http://www.iop.org/EJ/article/1464-4258/11/11/114003/joa9_11_114003.pdf?request-id=61616caa-78a3-48cf-b811-b98a69c5c590. Retrieved 2009-12-24.

- ↑ S. Tretyakov, A. Sihvola and L. Jylhä (2005). "Backward-wave regime and negative refraction in chiral composites". Photonics and Nanostructures - Fundamentals and Applications 3: 107. doi:10.1016/j.photonics.2005.09.008.

- ↑ Shelby, R. A.; Smith D.R.; Shultz S.; Nemat-Nasser S.C. (2001). "Microwave transmission through a two-dimensional, isotropic, left-handed metamaterial". Applied Physics Letters 78 (4): 489. doi:10.1063/1.1343489. http://people.ee.duke.edu/~drsmith/pubs_smith_group/Shelby_APL_(2001).pdf.

- ↑ Smith, D. R.; Padilla, WJ; Vier, DC; Nemat-Nasser, SC; Schultz, S (2000). "Composite Medium with Simultaneously Negative Permeability and Permittivity". Physical Review Letters 84 (18): 4184. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.84.4184. PMID 10990641. http://people.ee.duke.edu/~drsmith/pubs_smith_group/Smith_PRL_84_4184_(2000).pdf.

- ↑ "Photonic Metamaterials". Encyclopedia of Laser Physics and Technology. I & II. Wiley-VCH Verlag. 2008-18. pp. 1. http://www.rp-photonics.com/photonic_metamaterials.html. Retrieved 2009-10-01.

- ↑ Capolino, Filippo (2009-10). Applications of Metamaterials. Taylor & Francis, Inc.. pp. 29–1, 25–14, 22–1. ISBN 9781420054231. http://books.google.com/books?id=8M0IqvcsHisC&pg=PT640&dq=photonic+metamaterial#v=onepage&q=photonic%20metamaterial&f=false. Retrieved 2009-10-01.

- ↑ Capolino, Filippo (2009-10). "32". Theory and Phenomena of Metamaterials. Taylor & Francis. pp. 32–1. ISBN 9781420054255. http://books.google.com/books?id=0PMnYo8hva8C&pg=PT546.

- ↑ Pendry, J. B. (2000). "Negative Refraction Makes a Perfect Lens". Physical Review Letters 85 (18): 3966. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.3966. PMID 11041972.

- ↑ Fang, N.; Lee, H; Sun, C; Zhang, X (2005). "Sub-Diffraction-Limited Optical Imaging with a Silver Superlens". Science 308 (5721): 534. doi:10.1126/science.1108759. PMID 15845849.

- ↑ collection of free-download papers by J. Pendry

- ↑ Munk, B. A. (2009). Metamaterials: Critique and Alternatives. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley. ISBN 0470377046.

- ↑ A. Grbic and G.V. Eleftheriades (2004). "Overcoming the Diffraction Limit with a Planar Left-handed Transmission-line Lens". Physical Review Letters 92: 117403. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.117403. http://www.physik.hu-berlin.de/nano/lehre/nanophotonics/sl2.

- ↑ Fang, N; Lee, H; Sun, C; Zhang, X (2005). "Sub–Diffraction-Limited Optical Imaging with a Silver Superlens". Science 308 (5721): 534–7. doi:10.1126/science.1108759. PMID 15845849. Lay summary.

- ↑ "Metamaterials Bend Light to new Levels". Chemical & Engineering News 86 (33): 35. 2008.

- ↑ Yao, J; Liu, Z; Liu, Y; Wang, Y; Sun, C; Bartal, G; Stacy, AM; Zhang, X (2008). "Optical Negative Refraction in Bulk Metamaterials of Nanowires". Science 321 (5891): 930. doi:10.1126/science.1157566. PMID 18703734.

- ↑ "Metamaterials found to work for visible light". http://eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2007-01/dl-mft010407.php?light.

- ↑ "First Demonstration of a Working Invisibility Cloak". Office of News & Communications Duke University. http://www.dukenews.duke.edu/2006/10/cloakdemo.html. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ Schurig, D. et al. (2006). "Metamaterial Electromagnetic Cloak at Microwave Frequencies". Science 314: 977. doi:10.1126/science.1133628.

- ↑ A. Alu and N. Engheta (2005). "Achieving transparency with plasmonic and metamaterial coatings". Phys. Rev. E 72: 016623. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.72.016623.

- ↑ "Experts test cloaking technology". BBC News. 2006-10-19. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/6064620.stm. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ↑ "Engineers see progress in creating 'invisibility cloak'". http://www.purdue.edu/uns/x/2007a/070402ShalaevCloaking.html.

- ↑ Richard Merritt, "Next Generation Cloaking Device Demonstrated: Metamaterial renders object 'invisible'"

- ↑ Enoch, Stefan; Tayeb, GéRard; Sabouroux, Pierre; Guérin, Nicolas; Vincent, Patrick (2002). "A Metamaterial for Directive Emission". Physical Review Letters 89 (21): 213902. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.213902. PMID 12443413.

- ↑ Siddiqui, O.F.; Mo Mojahedi; Eleftheriades, G.V. (2003). "Periodically loaded transmission line with effective negative refractive index and negative group velocity". IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 51: 2619. doi:10.1109/TAP.2003.817556.

- ↑ Wu, B.-I.; W. Wang, J. Pacheco, X. Chen, T. Grzegorczyk and J. A. Kong (2005). "A Study of Using Metamaterials as Antenna Substrate to Ehance Gain". Progress in Electromagnetics Research (MIT, Cambridge, MA, USA: EMW Publishing) 51: 295–328. doi:0.2528/PIER04070701 (inactive 2010-03-17). http://ceta.mit.edu/PIER/pier51/17.0407071.Wu.WPCGK.pdf. Retrieved 2009-09-23.

- ↑ Johnson, R. Colin (2009-07-23). "Metamaterial cloak could render buildings 'invisible' to earthquakes". EETimes.com. http://www.eetimes.com/showArticle.jhtml?articleID=218600378. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- ↑ Barras, Colin (2009-06-26). "Invisibility cloak could hide buildings from quakes". New Scientist: pp. 1. http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn17378-invisibility-cloak-could-hide-buildings-from-quakes.html#. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ↑ "Analysis and Design of a Cylindrical EBG based directive antenna, Halim Boutayeb et al.". http://www.creer.polymtl.ca/Halim_Boutayeb/TAPCEBG.pdf.

- ↑ "‘Metafilms’ Can Shrink Radio, Radar Devices". http://newswise.com/articles/view/538769.

- ↑ "Invisibility Becomes More than Just a Fantasy". http://discovermagazine.com/2009/jan/007.

- ↑ MURI metamaterials, UC Berkely (2009). "Scalable and Reconfigurable Electromagnetic Metamaterials and Devices" (Link to web site). http://xlab.me.berkeley.edu/MURI/MURI.html. Retrieved 2009-12-08.

- ↑ U.S. Department of Defense, Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense (Public Affairs) (2009-05-08). "DoD Awards $260 Million in University Research Funding". DoD. http://www.defense.gov/releases/release.aspx?releaseid=12657. Retrieved 2009-12-08.

- ↑ Tretyakov, Prof. Sergei; President of the Association; Dr. Vladmir Podlozny; Secretary General (2009-12-13). "Metamorphose" (See the "About" section of this web site for information about this organization.). Metamaterials research and development. © 2009 Metamorphose VI. http://www.metamorphose-eu.org/index.php?option=com_frontpage&Itemid=1. Retrieved 2009-12-13.

- ↑ de Baas, =A. F.; and J. L. Vallés (2007-02-11). "Success stories in the Materials domain". Metamorphose (European Commission Directorate-General for Research. Directorate G – Industrial technologies. Unit G3 ‘Value – added Materials’.) Networks of Excellence Key for the future of EU research: 19. http://ec.europa.eu/research/industrial_technologies/pdf/noes-122007_en.pdf. Retrieved 2009-12-13.

External links

Research groups (in alphabetical order) having educational pages on metamaterials

- Min Qiu's Nanophotonics group, Royal Institute of Technology (KTH), Sweden

- Christophe Caloz' research group — Canada

- George Eleftheriades's research group — Canada

- Nader Engheta – US

- FGAN-FHR — Germany

- M. Saif Islam's Research Group, University of California at Davis – US

- Yang Hao's Group, Queen Mary, University of London – UK

- Sir John Pendry's group — free-download papers — Imperial College — UK

- Viktor Podolskiy's group — Oregon State University — US

- Shvets Research Group, University of Texas at Austin – US

- David Smith's research group — Duke University — US

- Costas Soukoulis at IESL, Greece — Photonic, Phononic & MetaMaterials Group

- Srinivas Sridhar's Lab & Group, Northeastern University

- Irina Veretennicoff's research group, Vrije Universiteit Brussel — Belgium

- Martin Wegener's Metamaterials group, Universität Karlsruhe (TH) — Germany

- Georgios Zouganelis's Metamaterials Group, NIT — Japan

- Xiang Zhang's group, Berkeley US

- Sergei Tretyakov's group, Helsinki University of Technology, Finland

- Gengkai Hu's group, Beijing Institute of Technology, Beijing

- Institute of Applied Phyisical Problems of BSU - Belarus

Internet portals

- MetaMaterials.net Web Group

- Journal "Metamaterials" published by Elsevier (homepage)

- Online articles: "Metamaterials" in ScienceDirect

- RSS feed for Metamaterials articles published in Physical Review Journals

- Virtual Institute for Artificial Electromagnetic Materials and Metamaterials ("METAMORPHOSE VI AISBL")

- European Network of Excellence "METAMORPHOSE" on Metamaterials

- SensorMetrix Formed with a specific directive to exploit the recent advances in electromagnetic metamaterials

More articles and presentations (most recent first)

- Dr. Sebastien Guenneau (Seismic MMs) Research on Metamaterials and Photonic Crystal Fibres

- UWB Tunable Delay System, Prof Christophe Caloz, Ecole Polytechnique de Montreal)

- Metaphotonics.de, Information about Photonic Metamaterials in Karlsruhe (HHNG Dr. Stefan Linden and Prof. Dr. Martin Wegener)

- Realistic raytraced images, videos and interactive web-based demonstrations of materials with negative index of refraction.

- Cloaking devices, nihility bandgap, LF magnetic enhancement, perfect radome NIT Japan

- Left-Handed Flat Lens HFSS Tutorial Electromagnetism Tutorial

- Journal of Optics A, February 2005 Special issue on Metamaterials

- Experimental Verification of a Negative Index of Refraction

- How To Make an Object Invisible

- Metamaterials hold key to cloak of invisibility

|

|||||