Menthol

| Menthol | |

|---|---|

|

-menthol-3D-vdW.png) |

|

|

|

(1R,2S,5R)-2-isopropyl-5-methylcyclohexanol

|

|

|

Other names

3-p-Menthanol,

Hexahydrothymol, Menthomenthol, peppermint camphor |

|

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 89-78-1 |

| ChemSpider | 15803 |

| RTECS number | OT0350000, racemic |

|

SMILES

CC(C)[C@@H]1CC[C@@H](C)C[C@H]1O

|

|

| Properties | |

| Molecular formula | C10H20O |

| Molar mass | 156.27 g mol−1 |

| Appearance | White or colorless crystalline solid |

| Density | 0.890 g·cm−3, solid (racemic or (−)-isomer) |

| Melting point |

36–38 °C (311 K), racemic |

| Boiling point |

212 °C (485 K) |

| Solubility in water | Slightly soluble, (−)-isomer |

| Hazards | |

| MSDS | External MSDS |

| R-phrases | R37/38, R41 |

| S-phrases | S26, S36 |

| Flash point | 93 °C |

| Related compounds | |

| Related alcohols | Cyclohexanol, Pulegol, Dihydrocarveol, Piperitol |

| Related compounds | Menthone, Menthene, Thymol, p-Cymene, Citronellal |

| Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C, 100 kPa) |

|

| Infobox references | |

Menthol is an organic compound made synthetically or obtained from peppermint or other mint oils. It is a waxy, crystalline substance, clear or white in color, which is solid at room temperature and melts slightly above. The main form of menthol occurring in nature is (−)-menthol, which is assigned the (1R,2S,5R) configuration. Menthol has local anesthetic and counterirritant qualities, and it is widely used to relieve minor throat irritation. Menthol also acts as a weak kappa Opioid receptor agonist.

Contents |

Structure

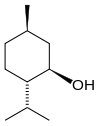

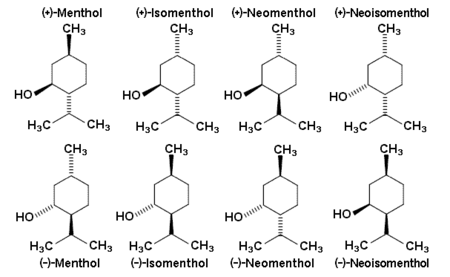

Natural menthol exists as one pure stereoisomer, nearly always the (1R,2S,5R) form (bottom left corner of the diagram below). The other seven stereoisomers are:

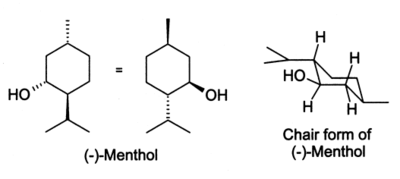

In the natural compound, the isopropyl group is in the trans orientation to both the methyl and hydroxyl groups. Thus it can be drawn in any of the ways shown:

In the ground state all three bulky groups in the chair are equatorial, making (−)-menthol and its enantiomer the most stable two isomers out of the eight.

There are two crystal forms for racemic menthol; these have melting points of 28 °C and 38 °C. Pure (−)-menthol has four crystal forms, of which the most stable is the α form, the familiar broad needles.

Biological properties

Menthol's ability to chemically trigger the cold-sensitive TRPM8 receptors in the skin is responsible for the well known cooling sensation that it provokes when inhaled, eaten, or applied to the skin.[1] In this sense it is similar to capsaicin, the chemical responsible for the spiciness of hot peppers (which stimulates heat sensors, also without causing an actual change in temperature).

Menthol has analgesic properties that are mediated through a selective activation of κ-opioid receptors.[2] Menthol also enhances the efficacy of ibuprofen in topical applications via vasodilation, which reduces skin barrier function.[3]

Occurrence

Mentha arvensis is the primary species of mint used to make natural menthol crystals and natural menthol flakes. This species is primarily grown in the Uttar Pradesh region in India.

(−)-Menthol (also called l-menthol or (1R,2S,5R)-menthol) occurs naturally in peppermint oil (along with a little menthone, the ester menthyl acetate and other compounds), obtained from Mentha x piperita.[4] Japanese menthol also contains a small percentage of the 1-epimer, (+)-neomenthol.

Production

As with many widely-used natural products, the demand for menthol greatly exceeds the supply from natural sources. Menthol is manufactured as a single enantiomer (94% ee) on the scale of 3,000 tons per year by Takasago International Corporation.[5] The process involves an asymmetric synthesis developed by a team led by Ryoji Noyori:

The process begins by forming an allylic amine from myrcene, which undergoes asymmetric isomerisation in the presence of a BINAP rhodium complex to give (after hydrolysis) enantiomerically pure R-citronellal. This is cyclised by a carbonyl-ene-reaction initiated by zinc bromide to isopulegol which is then hydrogenated to give pure (1R,2S,5R)-menthol.

Racemic menthol can be prepared simply by hydrogenation of thymol, and menthol is also formed by hydrogenation of pulegone.

Applications

Menthol is included in many products for a variety of reasons. These include:

- In non-prescription products for short-term relief of minor sore throat and minor mouth or throat irritation

- Examples: lip balms and cough medicines

- As an antipruritic to reduce itching

- As a topical analgesic to relieve minor aches and pains such as muscle cramps, sprains, headaches and similar conditions, alone or combined with chemicals like camphor, eucalyptus oil or capsaicin. In Europe it tends to appear as a gel or a cream, while in the US patches and body sleeves are very frequently used

- Examples: Tiger Balm, or IcyHot patches or knee/elbow sleeves

- In decongestants for chest and sinuses (cream, patch or nose inhaler)

- Examples: Vicks Vaporub, Mentholatum

- In certain medications used to treat sunburns, as it provides a cooling sensation (then often associated with aloe)

- As an additive in certain cigarette brands, for flavor, to reduce the throat and sinus irritation caused by smoking.

- Commonly used in oral hygiene products and bad-breath remedies like mouthwash, toothpaste, mouth and tongue-spray, and more generally as a food flavor agent; e.g. in chewing gum, candy

- In a soda to be mixed with water to obtain a very low alcohol drink or pure (brand Ricqlès which contains 80% alcohol in France). The alcohol is also used to alleviate nausea, in particular motion sickness, by pouring a few drops on a lump of sugar.

- As a pesticide against tracheal mites of honey bees

- In perfumery, menthol is used to prepare menthyl esters to emphasize floral notes (especially rose)

- In first aid products such as "mineral ice" to produce a cooling effect as a substitute for real ice in the absence of water or electricity (Pouch, Body patch/sleeve or cream)

- In various patches ranging from fever-reducing patches applied to children's foreheads to "foot patches" to relieve numerous ailments (the latter being much more frequent and elaborate in Asia, especially Japan: some varieties use "functional protrusions", or small bumps to massage ones feet as well as soothing them and cooling them down)

- In some beauty products such as hair-conditioners, based on natural ingredients (e.g. St. Ives)

In organic chemistry, menthol is used as a chiral auxiliary in asymmetric synthesis. For example, sulfinate esters made from sulfinyl chlorides and menthol can be used to make enantiomerically pure sulfoxides by reaction with organolithium reagents or Grignard reagents. Menthol reacts with chiral carboxylic acids to give diastereomic menthyl esters, which are useful for chiral resolution.

Reactions

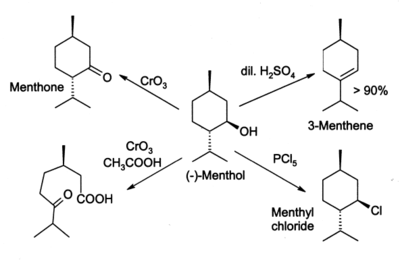

Menthol reacts in many ways like a normal secondary alcohol. It is oxidised to menthone by oxidising agents such as chromic acid or dichromate,[6] though under some conditions the oxidation can go further and break open the ring. Menthol is easily dehydrated to give mainly 3-menthene, by the action of 2% sulfuric acid. PCl5 gives menthyl chloride.

History

There is evidence[7] that menthol has been known in Japan for more than 2000 years, but in the West it was not isolated until 1771, by Hieronymus David Gaubius.[8] Early characterizations were done by Oppenheim,[9] Beckett,[10] Moriya,[11] and Atkinson.[12]

Compendial status

Toxicology and MSDS data

Currently no reported nutrient or herb interactions involve menthol. (−)-Menthol has low toxicity: Oral (rat) LD50: 3300 mg/kg; Skin (rabbit) LD50: 15800 mg/kg.

Notes and references

- ↑ R. Eccles (1994). "Menthol and Related Cooling Compounds". J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 46 (8): 618–630. PMID 7529306.

- ↑ Galeottia, N., Mannellia, L.D.C., Mazzantib, G., Bartolinia, A., Ghelardini, C. (2002). "Menthol: a natural analgesic compound". Neuroscience Letters 322 (3): 145–148. doi:10.1016/S0304-3940(01)02527-7.

- ↑ Braina, K.R., Greena, D.M., Dykesb, P.J., Marksb, R., Bola, T.S., The Role of Menthol in Skin Penetration from Topical Formulations of Ibuprofen 5% in vivo, Skin Pharmacol Physiol, 2006;19:17-21 [1]

- ↑ PDR for Herbal Medicines, 4th Edition, Thomson Healthcare, page 640. ISBN 978-1563636783

- ↑ http://www.flex-news-food.com/pages/13467/Flavour/Japan/japan-takasago-expand-menthol-production-iwata-plant.html

- ↑ L. T. Sandborn, "l-Menthone", Org. Synth., http://www.orgsyn.org/orgsyn/orgsyn/prepContent.asp?prep=cv1p0340; Coll. Vol. 1: 340

- ↑ J. L. Simonsen (1947). The Terpenes, Volume I (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 230–249.

- ↑ Adversoriorum varii argumentii, Liber unus, Leiden, 1771, p99.

- ↑ A. Oppenheim (1862). "On the camphor of peppermint". J. Chem. Soc. 15: 24. doi:10.1039/JS8621500024.

- ↑ G. H. Beckett and C. R. Alder Wright (1876). "Isomeric terpenes and their derivatives. (Part V)". J. Chem. Soc. 29: 1. doi:10.1039/JS8762900001.

- ↑ M. Moriya (1881). "Contributions from the Laboratory of the University of Tôkiô, Japan. No. IV. On menthol or peppermint camphor". J. Chem. Soc., Trans. 39: 77. doi:10.1039/CT8813900077.

- ↑ R. W. Atkinson and H. Yoshida (1882). "On peppermint camphor (menthol) and some of its derivatives". J. Chem. Soc., Trans. 41: 49. doi:10.1039/CT8824100049.

- ↑ Therapeutic Goods Administration (1999). "Approved Terminology for Medicines". http://www.tga.gov.au/docs/pdf/aan/aan.pdf. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ↑ 日本药局方. "Japanese Pharmacopoeia". http://jpdb.nihs.go.jp/jp15e/. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ↑ Sigma Aldrich. "DL-Menthol". http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/ProductDetail.do?lang=en&N4=W266507. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

Further reading

- E. E. Turner, M. M. Harris, Organic Chemistry, Longmans, Green & Co., London, 1952.

- Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 71st edition, CRC Press, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1990.

- The Merck Index, 7th edition, Merck & Co, Rahway, New Jersey, USA, 1960.

- Perfumer & Flavorist, December, 2007, Vol. 32, No.12, Pages 38–47

See also

- Camphor

- Menthol cigarettes

- Pulegone

- Vaporizer

- Vapor pressure

External links

- Colacot T. J. Platinum Metals Review 2002, 46(2), 82-83.

- Ryoji Noyori Nobel lecture (2001)

- Menthol Information

- Cooler than Menthol

- A review of menthol from the Science Creative Quarterly

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||