Cannabis (drug)

| Cannabis | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Dried flowers from the Cannabis sativa plant. Note the visible trichomes (commonly known as "crystals"), which contain large quantities of THC, CBD and other cannabinoids. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Phylum: | Magnoliophyta |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Cannabaceae |

| Genus: | Cannabis |

| Species: | C. sativa |

| Binomial name | |

| Cannabis sativa L.[1] Cannabis indica Lam. (putative)[1] |

|

Cannabis, also known as marijuana,[2] marihuana,[3] among many other names,a[›] refers to any number of preparations of the Cannabis plant intended for use as a psychoactive drug. The word marijuana comes from the Mexican Spanish mariguana.[4] According to the United Nations, cannabis "is the most widely used illicit substance in the world."[5]

The typical herbal form of cannabis consists of the flowers and subtending leaves and stalks of mature pistillate of female plants. The resinous form of the drug is known as hashish (or merely as 'hash').[6]

The major psychoactive chemical compound in cannabis is Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (commonly abbreviated as THC). At least 66 other cannabinoids are also present in cannabis, including cannabidiol (CBD), cannabinol (CBN) and tetrahydrocannabivarin (THCV) among many others, which are believed to result in different effects from those of THC alone.[7]

Cannabis use has been found to have occurred as long ago as the third millennium B.C.[8] In modern times, the drug has been used for recreational, religious or spiritual, and medicinal purposes. The UN estimated that in 2004 about 4% of the world's adult population (162 million people) use cannabis annually, and about 0.6% (22.5 million) use it on a daily basis.[9] The possession, use, or sale of cannabis preparations containing psychoactive cannabinoids became illegal in most parts of the world in the early 20th century. Since then, some countries have intensified the enforcement of cannabis prohibition, while others have reduced it.

Contents |

History

Cannabis is indigenous to Central and South Asia.[12] Evidence of the inhalation of cannabis smoke can be found in the 3rd millennium B.C., as indicated by charred cannabis seeds found in a ritual brazier at an ancient burial site in present day Romania.[8] Cannabis is also known to have been used by the ancient Hindus and Nihang Sikhs of India and Nepal thousands of years ago. The herb was called ganjika in Sanskrit (गांजा/গাঁজা ganja in modern Indic languages).[13][14] The ancient drug soma, mentioned in the Vedas, was sometimes associated with cannabis.[15]

Cannabis was also known to the ancient Assyrians, who discovered its psychoactive properties through the Aryans.[16] Using it in some religious ceremonies, they called it qunubu (meaning "way to produce smoke"), a probable origin of the modern word "cannabis".[17] Cannabis was also introduced by the Aryans to the Scythians and Thracians/Dacians, whose shamans (the kapnobatai—"those who walk on smoke/clouds") burned cannabis flowers to induce a state of trance.[18] Members of the cult of Dionysus, believed to have originated in Thrace (Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey), are also thought to have inhaled cannabis smoke. In 2003, a leather basket filled with cannabis leaf fragments and seeds was found next to a 2,500- to 2,800-year-old mummified shaman in the northwestern Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region of China.[19][20]

Cannabis has an ancient history of ritual use and is found in pharmacological cults around the world. Hemp seeds discovered by archaeologists at Pazyryk suggest early ceremonial practices like eating by the Scythians occurred during the 5th to 2nd century B.C., confirming previous historical reports by Herodotus.[21] One writer has claimed that cannabis was used as a religious sacrament by ancient Jews and early Christians[6][22] due to the similarity between the Hebrew word "qannabbos" ("cannabis") and the Hebrew phrase "qené bósem" ("aromatic cane"). It was used by Muslims in various Sufi orders as early as the Mamluk period, for example by the Qalandars.[23]

A study published in the South African Journal of Science showed that "pipes dug up from the garden of Shakespeare's home in Stratford upon Avon contain traces of cannabis."[24] The chemical analysis was carried out after researchers hypothesized that the "noted weed" mentioned in Sonnet 76 and the "journey in my head" from Sonnet 27 could be references to cannabis and the use thereof.[25]

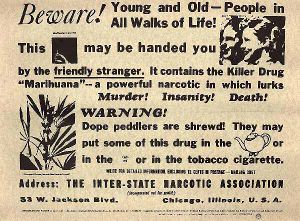

Cannabis was criminalized in various countries beginning in the early 20th century. It was outlawed in South Africa in 1911, in Jamaica (then a British colony) in 1913, and in the United Kingdom and New Zealand in the 1920s.[26] Canada criminalized marijuana in the Opium and Drug Act of 1923, before any reports of use of the drug in Canada. In 1925 a compromise was made at an international conference in Haag about the International Opium Convention that banned exportation of "Indian hemp" to countries that had prohibited its use, and requiring importing countries to issue certificates approving the importation and stating that the shipment was required "exclusively for medical or scientific purposes". It also required parties to "exercise an effective control of such a nature as to prevent the illicit international traffic in Indian hemp and especially in the resin". [27] In the United States the first restrictions for sale of cannabis came in 1906 (in District of Columbia).[28] In 1937, the Marijuana Transfer Tax Act was passed, and prohibited the production of hemp in addition to marijuana. The reasons that hemp was also included in this law are disputed. The Federal Bureau of Narcotics agents reported that fields with hemp were also used as a source for marijuana dealers. Other authors claim have claimed that it was passed in order to destroy the hemp industry,[29][30][31] largely as an effort of businessmen Andrew Mellon, Randolph Hearst, and the Du Pont family.[29][31] With the invention of the decorticator, hemp became a very cheap substitute for the paper pulp that was used in the newspaper industry.[29][32] Hearst felt that this was a threat to his extensive timber holdings. Mellon, Secretary of the Treasury and the wealthiest man in America, had invested heavily in the Du Pont families new synthetic fiber, nylon, which was also being outcompeted by hemp.[29]

Forms

Natural herbal form

The terms cannabis or marijuana generally refer to the dried flowers and subtending leaves and stems of the female cannabis plant. This is the most widely consumed form, containing 3% to 22% THC.[33][34] In contrast, cannabis strains used to produce industrial hemp contain less than 1% THC and are thus not valued for recreational use.[35]

Concentrated THC

Kief

Kief is a powder, rich in trichomes, which can be sifted from the leaves and flowers of cannabis plants and either consumed in powder form or compressed to produce cakes of hashish.[36]

Hashish

Hashish (also spelled hasheesh, hashisha, or simply hash) is a concentrated resin produced from the flowers of the female cannabis plant. Hash can often be more potent than marijuana and can be smoked or chewed.[37] It varies in color from black to golden brown depending upon purity.

Hash oil

Hash oil, or "butane honey oil" (BHO), is a mix of essential oils and resins extracted from mature cannabis foliage through the use of various solvents. It has a high proportion of cannabinoids (ranging from 40–90%).[38] and is used in a variety of cannabis foods.

Residue (resin)

Because of THC's adhesive properties, a sticky residue, most commonly known as "resin", builds up inside utensils used to smoke cannabis. It has tar-like properties but still contains THC as well as other cannabinoids. This buildup has some of the psychoactive properties of cannabis but is more difficult to smoke without discomfort caused to throat and lungs. This tar may also contain CBN, which is a breakdown product of THC. Cannabis users typically only smoke residue when cannabis is unavailable. Glass pipes may be water-steamed at a low temperature prior to scraping in order to make the residue easier to remove.[39] Alcohol is an effective solvent for cleaning residue from paraphernalia.

Potency

According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), "the amount of THC present in a cannabis sample is generally used as a measure of cannabis potency."[40] The three main forms of cannabis products are the herb (marijuana), resin (hashish), and oil (hash oil). The UNODC states that marijuana often contains 5% THC content, resin "can contain up to 20% THC content", and that "Cannabis oil may contain more than 60% THC content.".[40]

A scientific study published in 2000 in the Journal of Forensic Sciences (JFS) found that the potency (THC content) of confiscated cannabis in the United States (US) rose from "approximately 3.3% in 1983 and 1984", to "4.47% in 1997". It also concluded that "other major cannabinoids (i.e., CBD, CBN, and CBC)" (other chemicals in cannabis) "showed no significant change in their concentration over the years".[41] More recent research undertaken at the University of Mississippi's Potency Monitoring Project[42] has found that average THC levels in cannabis samples between 1975 and 2007 have increased from 4% in 1983 to 9.6% in 2007.

Australia's National Cannabis Prevention and Information Centre (NCPIC) states that the buds (flowers) of the female cannabis plant contain the highest concentration of THC, followed by the leaves. The stalks and seeds have "much lower THC levels".[43] The UN states that the leaves can contain ten times less THC than the buds, and the stalks one hundred times less THC.[40]

According to the "Talk to FRANK" (UK) website:

Recently, there has been an increased availability of strong herbal cannabis, containing on average 2-3 times the amount of the active compound, tetrahydrocannabinol or THC, as compared to the traditional imported ‘weed’. This strong cannabis includes:‘sinsemilla’ (a bud grown in the absence of male plants and which has no seeds); ‘homegrown’; ‘skunk’, which has a characteristic strong smell; and imported ‘netherweed’...

...it may not be possible to tell whether a particular sample of 'skunk' or ‘homegrown’ or ‘sinsemilla’ will have a higher potency than an equal amount of traditional herbal cannabis.

Of course, "homegrown", "netherweed" and "sinsemilla" are not always "strong", and not every strain of cannabis with a "characteristic strong smell" can be accurately named "skunk". "Traditional herbal cannabis" or "weed", has on the whole, always been subjectively "strong". While commentators have warned that greater cannabis "strength" could represent a health risk, others have noted that users readily learn to compensate by downsizing their dosage, thus benefiting from reductions in smoking side-hazards such as heat shock or carbon monoxide.

Adulterants

Adulterants in cannabis are less common than in other recreational drugs . Chalk (in the Netherlands) and glass particles (in the UK) have been used at times to make cannabis appear to be higher quality.[45][46][47] Increasing the weight of hashish products in Germany with lead caused lead intoxication in at least 29 users.[48] In the Netherlands two chemical analogs of Sildenafil (Viagra) were found in adulterated marijuana.[49]

- "Soap-Bar": according to both the "Talk to FRANK" website and the UKCIA website, "perhaps the most common type of cannabis found in the UK" can contain turpentine, tranquillizers, boot polish, henna and animal faeces - amongst several other things.[50][44] One small study of five "soap-bar" samples seized by UK Customs in 2001 found huge adulteration by many toxic substances, including soil, glue, engine oil and animal faeces.[51]

Routes of administration

Cannabis is consumed in many different ways, most of which involve inhaling smoke from pipes, bongs (small pipes with water chambers), paper-wrapped joints or tobacco-leaf-wrapped blunts.

Cannabis has also been used as an active ingredient in tablets, extracts, tinctures and compound medicines that were professionally formulated, manfactured, and sold to physicians and hospitals, as discussed below in 'Medical use'.

Vaporizer

A vaporizer heats herbal cannabis to 365–410 °F (185–210 °C), causing the active ingredients to evaporate into a gas without burning the plant material (the boiling point of THC is 390.4 °F (199.1 °C) at 760 mmHg pressure).[52] A lower proportion of toxic chemicals is released than by smoking, depending on the design of the vaporizer and the temperature at which it is set. This method of consuming cannabis produces markedly different effects than smoking due to the flash points of different cannabinoids; for example, CBN has a flash point of 212.7 °C (414.9 °F)[53] and would normally be present in smoke but might not be present in vapor.

As another alternative to smoking, cannabis may be consumed orally. However, the cannabis or its extract must be sufficiently heated or dehydrated to cause decarboxylation of its most abundant cannabinoid, tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA), into psychoactive THC.[54]

Cannabinoids can be leached from cannabis plant matter using high-proof spirits (often grain alcohol) to create a tincture, often referred to as Green Dragon.

Cannabis can also be consumed as a tea. THC is lipophilic and only slightly water soluble (with a solubility of 2.8 mg per liter),[55] so tea is made by first adding a saturated fat to hot water (i.e. cream or any milk except skim) with a small amount of cannabis, green or black tea leaves and honey or sugar, steeped for approximately 5 minutes.

Effects

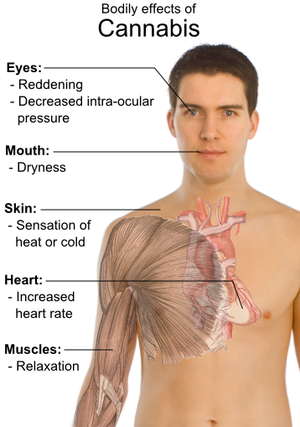

Cannabis has psychoactive and physiological effects when consumed. The minimum amount of THC required to have a perceptible psychoactive effect is about 10 micrograms per kilogram of body weight.[56] Aside from a subjective change in perception and, most notably, mood, the most common short-term physical and neurological effects include increased heart rate, lowered blood pressure, impairment of short-term episodic memory, working memory, psychomotor coordination, and concentration.[57] Long-term effects are less clear.[58][59]

Classification

While many drugs clearly fall into the category of either stimulant, depressant, or hallucinogen, cannabis exhibits a mix of all properties, perhaps leaning the most towards hallucinogenic or psychedelic properties, though with other effects quite pronounced as well. Though THC is typically considered the primary active component of the cannabis plant, various scientific studies have suggested that certain other cannabinoids like CBD may also play a significant role in its psychoactive effects.[10][60][61]

Medical use

Cannabis used medically does have several well-documented beneficial effects. Among these are: the amelioration of nausea and vomiting, stimulation of hunger in chemotherapy and AIDS patients, lowered intraocular eye pressure (shown to be effective for treating glaucoma), as well as general analgesic effects (pain reliever).b[›]

Cannabis was manufactured and sold by U.S. pharmaceutical companies from the 1880s through the 1930s, but the lack of documented information on the frequency and effectiveness of its use makes it difficult to evaluate its medicinal value. Cannabis in the form of a tincture and a fluidextract is documented in a 1929-30 catalog, Parke Davis & Co., which lists Cannabis, U.S.P. (American Cannabis), Fluid Extract No. 598 for $5 per pint; Cannabis, U.S.P. (East Indian Cannabis), Fluid Extract No. 106 for $36 per pint; and Cannabis (Tincture No. 14) for $3.60 per pint. The catalog states that Cannabis, U.S.P. fluid extract "is prepared from Cannabis sativa grown in America. Extensive pharmacological and clinical tests have shown that its medicinal action cannot be distinguished from that of the fluid made from imported East Indian cannabis. Introduced to the medical profession by us."[62]

Importantly, cannabis is listed in the 1929-1930 Physicians' Catalog of the Pharmaceutical and Biological Products of Parke, Davis & Company as an active ingredient in ten products for cough, colic, neuralgia, cholera mordus and other medical conditions, as well as a "narcotic, analgesic, and sedative." Under "Miscellaneous Products" are listed CHLOR-ANODYNE, containing in each fluid ounce morphine hydrocholoride, 2-7/8 grs.; Fluid Extract Cannabis, U.S.P., 46 mins.; Diluted hydrocyanic acid, 9 mins.; Chloroform, 46 grs.; Oil Peppermint, 1-1/2 mins.; and Tincture Capsicum, U.S.P., 3/4 min. (alcohol, 67%). It is described as "a promptly efficient and pleasant remedy for colic, cholera morbus, neuralgia, spasmodic pains, etc. Dose, 15 minims, to be repeated in half an hour if necessary." It was sold in ounce vials (65 cents per ounce), in 4 fl. oz. bottles at $1.95 per bottle, and in 16 fl.oz. bottles at $6.90 per bottle.[63] CODEINE COUGH SEDATIVE (Syrupus Codeinae Compositus) contains in each fluid ounce codeine phosphate, 1 gr.; Extract Cannabis, U.S.P., 1/2 gr.; White Pine bark, 32 grs.; Wild Cherry, 32 grs.; Eriodictyon, 16 grs.; Balsam Poplar buds (Balm of Gilead), 4 grs.; Choloroform, 2 grs.; and Glycerin, 120 mins. (alcohol 20%). Dose: 1 to 2 fluid drachms. The catalog states: "This combination is recommended for use in the treatment of dry bronchitis and irritating night cough. It is suitable for administration to children as well as adults, and can be continued from day to day in cases of subacute bronchitis with a minimum of 'drug' risk--for not only is codeine the safest of all opium derivatives, there is very little of it in this formula. A special indication for the use of Codeine Cough Sedative is the headache and nervous excitement that frequently attend paroxysms of coughing." This product was marketed in 16-fl. oz. bottles ($24.80 per dozen) and gallon bottles ($14.30 per gallon).[64]

The 1929-1930 Physicians' Catalog also lists compund medications containing cannabis that in some cases were apparently formulated by medical doctors, in its "Pills and Tablets" section, as follows: SEDATIVE (Dr. Brown), Compressed Tablet No. 322, was made from Sodium bromide, 2-1/2 grs.; Potassium bromide, 2-1/2 grs.; Ammonium bromide, 2-1/2 grs.; Tincture Hyoscyamus, 8 mins.; and Tincture Cannabis, 5 mins. The cost was 65 cents per 100 tablets, and $4.50 per 1,000 tablets."[65] NEURALGIC (Neuralgic Idiopathic),(Brown-Sequard), Pill No. 414, Ext. Hyoscyamus, 2/3 gr.; Ext. Ignatia, 1/2 gr.; Ext. Opium, 1/2 gr.; Ext. Cannabis, 1/4 gr.; Ext. Conium fruit, 2/3 gr.; Ext. Stramonium, 1/5 gr.; Ext. Aconite Root, 1/15 gr.; and Ext. Belladonna leaves, 1/6 gr." The cost was $2.55 per 100 pills, and $6.50 per 500. The formula for a "half-strength" pill is given in the footnote.[66] NEURALGIC, IMPROVED (Compressed Tablet No. 169), Quinine sulphate, 2 grs.; Acetanilid, 2 grs.; Ext. Hyoscyamus, 1/2 gr.; Arsenic trioxide, 1/100 gr.; Strychnine sulphate, 1/60 gr.; and Ext. Cannabis, 1/4 gr. Cost was $1.45 per 100 tablets.[67] CHLORODYNE (Compressed Tablet No. 14), Morphine hydrochloride, 1/6 gr.; Ext. Cannabis, 1/4 gr.; Nitroglycerin (Glyceryl trinitrate) 1/300 gr.; Ext. Hyoscyamus, 1/2 gr.; Olroresin Capsicum, 1/10 min.; and Oil Peppermint, q.s. The cost was $2.70 per 100 tablets. The formula for a "half-strength" tablet is given in the footnote.[68] In the section on "Medicinal Elixirs," is listed BROMIDE AND CHLORAL COMPOUND (No. 127), consisting of Chloral hydrate, 120 grs.; Potassium bromide, 120 grs.; Ext. Hyoscyamus, 1 gr.; and Ext. Cannabis, 1 gr. The cost was $19.80 per pint (16 fl. oz.) per dozen pints, and $15.20 per gallon bottle.[69] Although BROMIDE AND CHLORAL COMPOUND is listed as a Medicinal Elixir, the formula does not disclose any ingredients to render it in liquid form.

As cannabis is further legalized for medicinal use, it is possible that some of the foregoing compound medicines, whose formulas have been copied exactly as published, may be scientifically tested to determine whether they are effective medications.

Less confirmed individual studies also have been conducted indicating cannabis to be beneficial to a gamut of conditions running from multiple sclerosis to depression. Synthesized cannabinoids are also sold as prescription drugs, including Marinol (dronabinol in the United States and Germany) and Cesamet (nabilone in Canada, Mexico, The United States and The United Kingdom).b[›]

Currently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved smoked marijuana for any condition or disease in the United States, largely because good quality scientific evidence for its use from U.S. studies is lacking; however, a major barrier to acquiring the necessary evidence is the lack of federal funding for this kind of research.[70] Regardless, thirteen states have legalized cannabis for medical use.[71][72] Canada, Spain, The Netherlands and Austria have also legalized cannabis for medicinal use.[73][74]

Long-term effects

The smoking of cannabis is the most harmful method of consumption, as the inhalation of smoke from organic materials can cause various health problems.[75]

By comparison, studies on the vaporization of cannabis found that subjects were "only 40% as likely to report respiratory symptoms as users who do not vaporize, even when age, sex, cigarette use, and amount of cannabis consumed are controlled."[76] Another study found vaporizers to be "a safe and effective cannabinoid delivery system."[77][78]

.svg.png)

While a study in New Zealand of 79 lung-cancer patients suggested daily cannabis smokers have a 5.7 times higher risk of lung cancer than non-users,[80] another study of 2252 people in Los Angeles failed to find a correlation between the smoking of cannabis and lung, head or neck cancers.[81] Some studies have also found that moderate cannabis use may protect against head and neck cancers,[82] as well as lung cancer.[83] Some studies have shown that cannabidiol may also be useful in treating breast cancer.[84] These effects have been attributed to the well documented anti-tumoral properties of cannabinoids, specifically tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol.

Cannabis use has been assessed by several studies to be correlated with the development of anxiety, psychosis, and depression.[85][86] Indeed, a 2007 meta-analysis estimated that cannabis use is statistically associated, in a dose-dependent manner, to an increased risk in the development of psychotic disorders, including schizophrenia.[87] No causal mechanism has been proven, however, and the meaning of the correlation and its direction is a subject of debate that has not been resolved in the scientific community. Some studies assess that the causality is more likely to involve a path from cannabis use to psychotic symptoms rather than a path from psychotic symptoms to cannabis use,[88] while other studies assess the opposite direction of the causality, or hold cannabis to only form parts of a "causal constellation", while not inflicting mental health problems that would not have occurred in the absence of the cannabis use.[89][90]

Though cannabis use has at times been associated with stroke, there is no firmly established link, and potential mechanisms are unknown.[91] Similarly, there is no established relationship between cannabis use and heart disease, including exacerbation of cases of existing heart disease.[92] Though some fMRI studies have shown changes in neurological function in long term heavy cannabis users, no long term behavioral effects after abstinence have been linked to these changes.[93]

Detection of use

THC and its major (inactive) metabolite, THC-COOH, can be quantitated in blood, urine, hair, oral fluid or sweat using chromatographic techniques as part of a drug use testing program or a forensic investigation of a traffic or other criminal offense. The concentrations obtained from such analyses can often be helpful in distinguishing active use from passive exposure, prescription use from illicit use, elapsed time since use, and extent or duration of use. These tests cannot, however, distinguish authorized cannabis smoking for medical purposes from unauthorized recreational smoking.[94] Commercial cannabinoid immunoassays, often employed as the initial screening method when testing physiological specimens for marijuana presence, have different degrees of cross-reactivity with THC and its metabolites. Urine contains predominantly THC-COOH, while hair, oral fluid and sweat contain primarily THC. Blood may contain both substances, with the relative amounts dependent on the recency and extent of usage.[95][96][97][98]

The Duquenois-Levine test is commonly used as a screening test in the field, but it cannot definitively confirm the presence of marijuana, as a large range of substances have been shown to give false positives. Despite this, it is common in the United States for prosecutors to seek plea bargains on the basis of positive D-L tests, claiming them definitive, or even to seek conviction without the use of gas chromatography confirmation, which can only be done in the lab.[99]

Gateway drug theory

Some claim that trying cannabis increases the probability that users will eventually use "harder" drugs. This hypothesis has been one of the central pillars of anti-cannabis drug policy in the United States,[100] though the validity and implications of these hypotheses are highly debated.[101] Studies have shown that tobacco smoking is a better predictor of concurrent illicit hard drug use than smoking cannabis.[102]

No widely accepted study has ever demonstrated a cause-and-effect relationship between the use of cannabis and the later use of harder drugs like heroin and cocaine. However, the prevalence of tobacco cigarette advertising and the practice of mixing tobacco and cannabis together in a single large joint, common in Europe, are believed to be cofactors in promoting nicotine dependency among young persons investigating cannabis.[103]

A 2005 comprehensive review of the literature on the cannabis gateway hypothesis found that pre-existing traits may predispose users to addiction in general, the availability of multiple drugs in a given setting confounds predictive patterns in their usage, and drug sub-cultures are more influential than cannabis itself. The study called for further research on "social context, individual characteristics, and drug effects" to discover the actual relationships between cannabis and the use of other drugs.[104]

A new user of cannabis who feels there is a difference between anti-drug information and their own experiences will apply this distrust to public information about other, more powerful drugs. Some studies state that while there is no proof for this gateway hypothesis, young cannabis users should still be considered as a risk group for intervention programs.[105] Other findings indicate that hard drug users are likely to be "poly-drug" users, and that interventions must address the use of multiple drugs instead of a single hard drug.[106]

Another gateway hypothesis is that while cannabis is not as harmful or addictive as other drugs, a gateway effect may be detected as a result of the "common factors" involved with using any illegal drug. Because of its illegal status, cannabis users are more likely to be in situations which allow them to become acquainted with people who use and sell other illegal drugs.[107][108] By this argument, some studies have shown that alcohol and tobacco may be regarded as gateway drugs.[102] However, a more parsimonious explanation could be that cannabis is simply more readily available (and at an earlier age) than illegal hard drugs, and alcohol/tobacco are in turn easier to obtain earlier than cannabis (though the reverse may be true in some areas), thus leading to the "gateway sequence" in those people who are most likely to experiment with any drug offered.[101]

Legal status

Since the beginning of the 20th century, most countries have enacted laws against the cultivation, possession or transfer of cannabis. These laws have impacted adversely on the cannabis plant's cultivation for non-recreational purposes, but there are many regions where, under certain circumstances, handling of cannabis is legal or licensed. Many jurisdictions have lessened the penalties for possession of small quantities of cannabis, so that it is punished by confiscation and sometimes a fine, rather than imprisonment, focusing more on those who traffic the drug on the black market.

In some areas where cannabis use has been historically tolerated, some new restrictions have been put in place, such as the closing of cannabis coffee shops near the borders of the Netherlands,[109] closing of coffee shops near secondary schools in the Netherlands and crackdowns on "Pusher Street" in Christiania, Copenhagen in 2004.[110][111]

Some jurisdictions use free voluntary treatment programs and/or mandatory treatment programs for frequent known users. Simple possession can carry long prison terms in some countries, particularly in East Asia, where the sale of cannabis may lead to a sentence of life in prison or even execution. More recently however, many political parties, non-profit organizations and causes based on the legalization of medical cannabis and/or legalizing the plant entirely (with some restrictions) have emerged.

Price

The price or street value of cannabis varies strongly by region and area. In addition, some dealers may sell potent buds at a higher price.[112]

In the United States, cannabis is overall the #4 value crop, and is #1 or #2 in many states including California, New York and Florida, averaging $3,000/lb.[113][114] It is believed to generate an estimated $36 billion market.[115] Most of the money is spent not on growing and producing but on smuggling the supply to buyers. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime claims in its 2008 World Drug Report that typical U.S. retail prices are 10-15 dollars per gram (approximately $290 to $430 per ounce). Street prices in North America are known to range from about $150 to $250 per ounce, depending on quality.[116]

The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction reports that typical retail prices in Europe for cannabis varies from 2€ to 14€ per gram, with a majority of European countries reporting prices in the range 4–10€.[117] In the United Kingdom, a cannabis plant has an approximate street value of £300.[118]

Truth serum

Cannabis was used as a truth serum by the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), a US government intelligence agency formed during World War II. In the early 1940s, it was the most effective truth drug developed at the OSS labs at St. Elizabeths Hospital; it caused a subject "to be loquacious and free in his impartation of information."[119]

In May 1943, Major George Hunter White, head of OSS counter-intelligence operations in the US, arranged a meeting with Augusto Del Gracio, an enforcer for gangster Lucky Luciano. Del Gracio was given cigarettes spiked with THC concentrate from cannabis, and subsequently talked openly about Luciano's heroin operation. On a second occasion the dosage was increased such that Del Gracio passed out for two hours.[119]

Breeding and cultivation

It is often claimed by growers and breeders of herbal cannabis that advances in breeding and cultivation techniques have increased the potency of cannabis since the late 1960s and early '70s, when THC was first discovered and understood. However, potent seedless marijuana such as "Thai sticks" were already available at that time. Sinsemilla (Spanish for "without seed") is the dried, seedless inflorescences of female cannabis plants. Because THC production drops off once pollination occurs, the male plants (which produce little THC themselves) are eliminated before they shed pollen to prevent pollination. Advanced cultivation techniques such as hydroponics, cloning, high-intensity artificial lighting, and the sea of green method are frequently employed as a response (in part) to prohibition enforcement efforts that make outdoor cultivation more risky. These intensive horticultural techniques have made it possible to grow strains with fewer seeds and higher potency. It is often cited that the average levels of THC in cannabis sold in United States rose dramatically between the 1970s and 2000, but such statements are likely skewed because of undue weight given to much more expensive and potent, but less prevalent samples.[120]

"Skunk" refers to several named strains of potent cannabis, grown through selective breeding and often hydroponics. It is a cross-breed of Cannabis sativa and C. indica (although other strains of this mix exist in abundance). Skunk cannabis potency ranges usually from 6% to 15% and rarely as high as 20%. The average THC level in coffee shops in the Netherlands is about 18–19%.[121]

Skunk can sometimes be incorrectly mistaken for all types of female herbal cannabis.[122]

After revisions to cannabis rescheduling in the UK, the government moved cannabis back from a class C to a class B drug. A purported reason was the appearance of high potency cannabis.[123]

It is noted that one of the earliest strains of skunk to appear was that of "SKUNK #1", which has been inbred since 1978,[124] but high potency herbal cannabis has been around even longer.

A Dutch double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, cross-over study examining male volunteers aged 18–45 years with a self-reported history of regular cannabis use concluded that smoking of cannabis with high THC levels (marijuana with 9–23% THC), as currently sold in coffee shops in the Netherlands, may lead to higher THC blood-serum concentrations. This is reflected by an increase of the occurrence of impaired psychomotor skills, particularly among younger or inexperienced cannabis smokers, who do not adapt their smoking style to the higher THC content.[125] High THC concentrations in cannabis was associated with a dose-related increase of physical effects (such as increase of heart rate, and decrease of blood pressure) and psychomotor effects (such as reacting more slowly, being less concentrated, making more mistakes during performance testing, having less motor control, and experiencing drowsiness). It was also observed during the study that the effects from a single joint at times lasted for more than eight hours. Reaction times remained impaired five hours after smoking, when the THC serum concentrations were significantly reduced, but still present. The researchers suggested that THC may accumulate in blood-serum when cannabis is smoked several times per day.

Another study showed that consumption of 15 mg of Δ9-THC resulted in no impairment in performance of implicit memory tasks occurring over a three-trial selective reminding task after two hours. In several tasks, Δ9-THC increased both speed and error rates, reflecting “riskier” speed–accuracy trade-offs.[126]

In arts and literature

- Les paradis artificiels by Charles Baudelaire

- The Hasheesh Eater by Fitz Hugh Ludlow

See also

- Cannabis plant

- Bhang

- Cannabinoids

- Cannabidiol (CBD)

- Cannabinol (CBN)

- Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)

- Tetrahydrocannabivarin (THCV)

- Cannabis drug strains

- Hash or hashish

- Hash oil or honey oil

- Hemp oil

- Kief

- Cannabis health

- Medical cannabis

- Cannabis mental health

- Depersonalization disorder

- Smoking cessation (cannabis)

- Cannabis legality

- Legal history of cannabis in the United States

- 1937 Marihuana Tax Act

- Cannabis political parties

- Global Marijuana March

- International Opium Convention

- Legal and medical status of cannabis

- Legality of cannabis by country

- Marijuana Control, Regulation, and Education Act

- Marijuana Policy Project

- National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws

- Cannabis use demographics

- Adult lifetime cannabis use by country

- Annual cannabis use by country

Notes

Footnotes

^ a: Weed, pot, buddha or bud, Mary Jane, grass, herb, dope, schwag, and reefer, are among the many other nicknames for marijuana or cannabis as a drug.[127]

^ b: Sources for this section (as well as far more information) can be found in the Medical cannabis article.

Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 John H. Wiersema. "Cannabis sativa information from NPGS/GRIN". Ars-grin.gov. http://www.ars-grin.gov/cgi-bin/npgs/html/taxon.pl?8862. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ↑ See, Etymology of marijuana.

- ↑ Company, Houghton Mifflin; American Heritage Dictionaries (2007-11-14). Spanish Word Histories and Mysteries. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 142. ISBN 0618910549, 9780618910540. http://books.google.com/?id=VTYBbGybtNEC&pg=PA142.

- ↑ Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (6th ed.), Oxford University Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-19-920687-2

- ↑ UNODC. World Drug Report 2010. United Nations Publication. pp. 198. http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/WDR-2010.html. Retrieved 2010-07-19.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Matthew J. Atha (Independent Drug Monitoring Unit). "Types of Cannabis Available in the United Kingdom (UK)". http://www.idmu.co.uk/can.htm.

- ↑ Fusar-Poli P, Crippa JA, Bhattacharyya S, et al. (January 2009). "Distinct effects of {delta}9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol on neural activation during emotional processing". Archives of General Psychiatry 66 (1): 95–105. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.519. PMID 19124693. http://archpsyc.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=19124693. Retrieved 2009-09-26.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Rudgley, Richard (1998). Lost Civilisations of the Stone Age.. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0-6848-5580-1.

- ↑ United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2006) (PDF). Cannabis: Why We Should Care.. 1. S.l.: United Nations. 14. ISBN 9-2114-8214-3. http://www.unodc.org/pdf/WDR_2006/wdr2006_chap2_biggest_market.pdf.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Stafford, Peter (1992). Psychedelics Encyclopedia. Berkeley, California: Ronin Publishing, Inc.. ISBN 0-914171-51-8. http://books.google.com/?id=Ec5hNgYWHtkC&printsec=frontcover.

- ↑ Matthews, A.; Matthews, L. (2007). Learning Chinese Characters. p. 336. ISBN 9780804838160. http://books.google.com/?id=YweFHwPd05EC&pg=PA336&lpg=PA336&dq=hemp+wood+shelter.

- ↑ "Marijuana and the Cannabinoids", ElSohly (p.8)

- ↑ Leary, Thimothy (1990). Tarcher & Putnam. ed. Flashbacks. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 0-8747-7870-0.

- ↑ Miller, Ga (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica. 34 (11th ed.). 761–762. doi:10.1126/science.34.883.761. http://www.1911encyclopedia.org/Hemp.

- ↑ Rudgley, Richard (1998). Little, Brown, et al.. ed. The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Substances. http://www.huxley.net/soma/index.html.

- ↑ Franck, Mel (1997). Marijuana Grower's Guide. Red Eye Press. ISBN 0-9293-4903-2. p. 3.

- ↑ Rubin, Vera D. (1976). Cannabis and Culture. Campus Verlag. ISBN 3-5933-7442-0. p. 305.

- ↑ Cunliffe, Barry W. (2001). The Oxford Illustrated History of Prehistoric Europe. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-1928-5441-0. p. 405.

- ↑ "Lab work to identify 2,800-year-old mummy of shaman". People's Daily Online. 2006. http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/200612/23/eng20061223_335258.html.

- ↑ Hong-En Jiang et al. (2006). "A new insight into Cannabis sativa (Cannabaceae) utilization from 2500-year-old Yanghai tombs, Xinjiang, China". Journal of Ethnopharmacology 108 (3): 414–422. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2006.05.034. PMID 16879937. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6T8D-4K7WC0F-2&_user=10&_coverDate=12%2F06%2F2006&_rdoc=17&_fmt=summary&_orig=browse&_srch=doc-info(%23toc%235084%232006%23998919996%23636769%23FLA%23display%23Volume)&_cdi=5084&_sort=d&_docanchor=&view=c&_ct=23&_acct=C000050221&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=3e6ac8940b4b86b94935cd7a7d7bc19d.

- ↑ Walton, Robert P. (1938). Marijuana, America's New Drug Problem. J. B. Lippincott. p. 6.

- ↑ "Cannabis linked to Biblical healing". BBC News. 2003-01-06. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/2633187.stm. Retrieved 2009-12-31.

- ↑ Ibn Taymiyya (2001). Le haschich et l'extase. Beyrouth: Albouraq. ISBN 2-8416-1174-4.

- ↑ "Bard 'used drugs for inspiration'". BBC News (BBC). 2001-03-01. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/1195939.stm. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- ↑ "Drugs clue to Shakespeare's genius". CNN (Turner Broadcasting System). 2001-03-01. http://edition.cnn.com/2001/WORLD/europe/UK/03/01/shakespeare.cannabis/. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- ↑ "Debunking the Hemp Conspiracy Theory". http://www.alternet.org/drugreporter/77339/?page=entire.

- ↑ W.W. WILLOUGHBY: OPIUM AS AN INTERNATIONAL PROBLEM, BALTIMORE, THE JOHNS HOPKINS PRESS, 1925

- ↑ STATEMENT OF DR. WILLIAM C. WOODWARD

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 French, Laurence; Magdaleno Manzanárez (2004). NAFTA & neocolonialism: comparative criminal, human & social justice. University Press of America. pp. 129. ISBN 9780761828907. http://books.google.com/?id=4ozF1Yg-c4MC&pg=PA129.

- ↑ Mitchell Earlywine (2005). Understanding marijuana: a new look at the scientific evidence. Oxford University Press. p. 24. ISBN 9780195182958. http://books.google.com/books?id=r9wPbxMAG8cC&pg=PA24.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Peet, Preston (2004). Under the influence: the disinformation guide to drugs. The Disinformation Company. pp. 55. ISBN 9781932857009. http://books.google.com/?id=uC0_YznYjScC&pg=PA55.

- ↑ Sterling Evans (2007). Bound in twine: the history and ecology of the henequen-wheat complex for Mexico and the American and Canadian Plains, 1880-1950. Texas A&M University Press. p. 27. ISBN 9781585445967. http://books.google.com/books?id=_wFkZgyuGFAC&pg=PA27.

- ↑ "High Times in Ag Science: Marijuana More Potent Than Ever | Wired Science". Wired.com. 2008-12-22. http://www.wired.com/wiredscience/2008/12/high-times-in-a/. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ↑ "Marijuana- Definitions from Dictionary.com". dictionary.reference.com. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/Marijuana.

- ↑ "Hemp Facts". Naihc.org. http://www.naihc.org/hemp_information/hemp_facts.html. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ↑ "Kief | Cannabis Culture Magazine". Cannabisculture.com. http://www.cannabisculture.com/v2/articles/4220.html. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ↑ "Hashish - Definitions from Dictionary.com". dictionary.reference.com. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/Hashish.

- ↑ "Hash Oil Info.". http://www.a1b2c3.com/drugs/hash005.htm.

- ↑ "Pipe Residue Information.". http://www.cannabisculture.com/v2/articles/3603.html.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 "Why Does Cannabis Potency Matter?". United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2009-06-29. http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/frontpage/2009/June/why-does-cannabis-potency-matter.html.

- ↑ ElSohly MA, Ross SA, Mehmedic Z, Arafat R, Yi B, Banahan BF (January 2000). "Potency Trends of delta9-THC and Other Cannabinoids in Confiscated Marijuana from 1980-1997.". Journal of Forensic Sciences 45 (1): 24–30. PMID 10641915.

- ↑ Olemiss.edu

- ↑ "Cannabis Potency.". National Cannabis Prevention and Information Centre. http://ncpic.org.au/workforce/cannabisinfo/factsheets/article/cannabis-potency.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 "FRANK - Cannabis". Talktofrank.com. http://www.talktofrank.com/drugs.aspx?id=172. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ↑ "Electronenmicroscopisch onderzoek van vervuilde wietmonsters". http://www.rivm.nl/bibliotheek/digitaaldepot/BriefrapportWiet.pdf.

- ↑ "Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety - Contamination of herbal or 'skunk-type' cannabis with glass beads". http://www.dhsspsni.gov.uk/hss_md_3-2007.pdf.

- ↑ "Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety - Update on seizures of cannabis contaminated with glass particles". http://www.dhsspsni.gov.uk/hss_md_11-2007__update.pdf.

- ↑ Busse F, Omidi L, Timper K, et al. (April 2008). "Lead poisoning due to adulterated marijuana". N. Engl. J. Med. 358 (15): 1641–2. doi:10.1056/NEJMc0707784. PMID 18403778.

- ↑ Venhuis BJ, de Kaste D (November 2008). "Sildenafil analogs used for adulterating marijuana". Forensic Sci. Int. 182 (1-3): e23–4. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2008.09.002. PMID 18945564.

- ↑ "UKCIA Soapbar warning - cannabis conamination - don't buy soapbar!". Ukcia.org. http://www.ukcia.org/activism/soapbar.php. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ↑ "Feature - Dr Russell Newcome on the ACMD report on cannabis : 2006-02-07". Lifeline Project. 2006-02-07. http://www.lifelineproject.co.uk/Dr-Russell-Newcome-on-the-ACMD-report-on-cannabis_25.php. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ↑ "ChemSpider - THC". http://www.chemspider.com/Chemical-Structure.15266.html.

- ↑ "ChemSpider - Cannabinol". http://www.chemspider.com/Chemical-Structure.2447.html.

- ↑ "Decarboxylation - Does Marijuana Have to be Heated to Become Psychoactive?". http://www.cannabisculture.com/articles/2794.html.

- ↑ "ChemIDplus Lite". chem.sis.nlm.nih.gov. http://chem.sis.nlm.nih.gov/chemidplus/ProxyServlet?objectHandle=Search&actionHandle=getAll3DMViewFiles&nextPage=jsp%2Fcommon%2FChemFull.jsp%3FcalledFrom%3Dlite&chemid=001972083&formatType=_3D.

- ↑ "Marijuana and the Brain, Part II: The Tolerance Factor". http://www.marijuanalibrary.org/brain2.txt.

- ↑ Riedel G, Davies SN (2005). "Cannabinoid function in learning, memory and plasticity". Handb Exp Pharmacol (168): 445–477. PMID 16596784. http://www.springerlink.com/openurl.asp?genre=chapter&issn=0171-2004&volume=&page=445.

- ↑ Long-Term Effects of Exposure to Cannabis.

- ↑ Adverse Effects of Cannabis on Health: An Update of the Literature Since 1996.

- ↑ McKim, William A (2002). Drugs and Behavior: An Introduction to Behavioral Pharmacology (5th Edition).. Prentice Hall. p. 400. ISBN 0-13-048118-1.

- ↑ "Information on Drugs of Abuse.". Commonly Abused Drug Chart. http://www.nida.nih.gov/DrugPages/DrugsofAbuse.html.

- ↑ 1929-1930 Physicians' Catalog of the Pharmaceutical and Biological Products of Parke, Davis & Company. Detroit: Parke, Davis & Co., pages 82-83.

- ↑ 1929-1930 Physicians' Catalog of the Pharmaceutical and Biological Products of Parke, Davis & Company. Detroit: Parke, Davis & Co., page 12.

- ↑ 1929-1930 Physicians' Catalog of the Pharmaceutical and Biological Products of Parke, Davis & Company. Detroit: Parke, Davis & Co., page 17.

- ↑ 1929-1930 Physicians' Catalog of the Pharmaceutical and Biological Products of Parke, Davis & Company. Detroit: Parke, Davis & Co., page 194.

- ↑ 1929-1930 Physicians' Catalog of the Pharmaceutical and Biological Products of Parke, Davis & Company. Detroit: Parke, Davis & Co., page 186. NEURALGIC (Neuralgic Idiopathic, half-strength), (Brown-Sequard), Pill No. 415, is Ext. Hyoscyamus, 1/3 gr.; Ext. Ignatia, 1/4 gr.; Ext. Opium, 1/4 gr.; Ext. Cannabis, 1/8 gr.; Ext. Conium fruit, 1/3 gr.; Ext. Stramonium, 1/10 gr.; Ext. Aconite root, 1/30 gr.; and Ext. Belladonna leaves, 1/12 gr. The cost was $1.45 per 100 pills and $6.50 per 500.

- ↑ 1929-1930 Physicians' Catalog of the Pharmaceutical and Biological Products of Parke, Davis & Company. Detroit: Parke, Davis & Co., page 187.

- ↑ 1929-1930 Physicians' Catalog of the Pharmaceutical and Biological Products of Parke, Davis & Company. Detroit: Parke, Davis & Co., page 171. CHLORODYNE No. 2 (Chocolate-coated Tablet No. 186), Morphine hydrochloride, 1/12 gr.; Ext. Cannabis, 1/8 gr.; Nitroglycerin (Glyceryl trinitrate) 1/600 gr.; Ext. Hyoscyamus, 1/4 gr.; Olroresin Capsicum, 1/20 min.; and Oil Peppermint, q.s. The cost was $1.60 per 100 tablets.

- ↑ 1929-1930 Physicians' Catalog of the Pharmaceutical and Biological Products of Parke, Davis & Company. Detroit: Parke, Davis & Co., page 97.

- ↑ Harris, G. (18 January 2010). "Researchers find study of medical marijuana discouraged". New York Times (New York). http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/19/health/policy/19marijuana.html?hpw. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- ↑ "Medical Frequently Asked Questions". NORML. http://norml.org/index.cfm?Group_ID=3387. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ↑ FDA: Inter-Agency Advisory Regarding Claims That Smoked Marijuana Is a Medicine

- ↑ ""Frequently Asked Questions - Medical Marihuana"". Hc-sc.gc.ca. http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/marihuana/about-apropos/faq-eng.php. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ↑ "Medical cannabis - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia". En.wikipedia.org. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medical_cannabis#Legal_and_medical_status. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ↑ Franjo Grotenhermen (June 2001). "Harm Reduction Associated with Inhalation and Oral Administration of Cannabis and THC.". Journal of Cannabis Therapeutics 1 (3-4): 133–152. doi:10.1300/J175v01n03_09. http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/content~db=all?content=10.1300/J175v01n03_09.

- ↑ Earleywine M, Barnwell SS (2007). "Decreased Respiratory Symptoms in Cannabis Users Who Vaporize.". Harm Reduction Journal 4: 11. doi:10.1186/1477-7517-4-11. PMID 17437626.

- ↑ Abrams DI, Vizoso HP, Shade SB, Jay C, Kelly ME, Benowitz NL (November 2007). "Vaporization as a Smokeless Cannabis Delivery System: A Pilot Study.". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 82 (5): 572–578. doi:10.1038/sj.clpt.6100200. PMID 17429350. http://cat.inist.fr/?aModele=afficheN&cpsidt=17821306.

- ↑ Hazekamp A, Ruhaak R, Zuurman L, van Gerven J, Verpoorte R (June 2006). "Evaluation of a vaporizing device (Volcano) for the pulmonary administration of tetrahydrocannabinol". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 95 (6): 1308–1317. doi:10.1002/jps.20574. PMID 16637053.

- ↑ PMID 17382831 (PubMed)

Citation will be completed automatically in a few minutes. Jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ "Cannabis bigger cancer risk than cigarettes: study". Thomson Reuters. http://www.reuters.com/article/healthNews/idUSHKG10478820080129.

- ↑ "Study Finds No Link Between Marijuana Use And Lung Cancer". Science Daily. 2006-05-26. http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2006/05/060526083353.htm.

- ↑ Liang C, McClean MD, Marsit C, et al. (August 2009). "A population-based case-control study of marijuana use and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma". Cancer Prev Res (Phila Pa) 2 (8): 759–68. doi:10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0048. PMID 19638490.

- ↑ Kaufman, Marc ([2006-5-26]). "Study Finds No Cancer-Marijuana Connection". Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/05/25/AR2006052501729_pf.html. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "Marijuana compound may stop spread of breast cancer". Fox News. 2007-11-19. http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,312132,00.html.

- ↑ Henquet C, Krabbendam L, Spauwen J, et al. (January 2005). "Prospective Cohort Study of Cannabis Use, Predisposition for Psychosis, and Psychotic Symptoms in Young People.". British Medical Journal 330 (7481): 11. doi:10.1136/bmj.38267.664086.63. PMID 15574485.

- ↑ Patton GC, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Degenhardt L, Lynskey M, Hall W (November 2002). "Cannabis Use and Mental Health in Young People: Cohort Study.". British Medical Journal 325 (7374): 1195–1198. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7374.1195. PMID 12446533.

- ↑ Moore THM, Zammit S, Lingford-Hughes A et al. (2007). "Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review". Lancet 370 (9584): 319–328. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61162-3. PMID 17662880.

- ↑ Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM (March 2005). "Tests of Causal Linkages Between Cannabis Use and Psychotic Symptoms.". Addiction 100 (3): 354–366. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01001.x. PMID 15733249.

- ↑ Hall, Wayne; Degenhardt, Lousia; Teesson, Maree. "Cannabis Use and Psychotic Disorders: An Update". Office of Public Policy and Ethics, Institute for Molecular Bioscience University of Queensland Australia, and National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre University of New South Wales Australia published in Drug and Alcohol Review (December 2004). Vol 23 Issue 4. pp. 433–443.

- ↑ Arseneault, Louise; Cannon, Mary; Wiitton, John; Murray, Robin M. "Causal Association Between Cannabis and Psychosis: Examination of the Evidence". Institute of Psychiatry published in British Journal of Psychiatry (2004). #184, pp. 110–117.

- ↑ Halpin SF, Yeoman L, Dundas DD (October 1991). "Radiographic examination of the lumbar spine in a community hospital: an audit of current practice". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 303 (6806): 813–815. doi:10.1136/bmj.303.6806.813. PMID 1932970.

- ↑ Mukamal KJ, Maclure M, Muller JE, Mittleman MA (March 2008). "An exploratory prospective study of marijuana use and mortality following acute myocardial infarction". American Heart Journal 155 (3): 465–70. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2007.10.049. PMID 18294478. PMC 2276621. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0002-8703(07)01044-7.

- ↑ Gonzalez R (September 2007). "Acute and Non-Acute Effects of Cannabis on Brain Functioning and Neuropsychological Performance". Neuropsychology Review 17 (3): 347–61. doi:10.1007/s11065-007-9036-8. PMID 17680367.

- ↑ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp 1513-1518.

- ↑ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp 1513-1518.

- ↑ Coulter C, Taruc M, Tuyay J, Moore C. Quantitation of tetrahydrocannabinol in hair using immunoassay and liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometric detection. Drug Test. Anal. 1: 234-239, 2009.

- ↑ DM Schwope, G Milman and MA Huestis. Validation of an enzyme immunoassay for detection and semiquantification of cannabinoids in oral fluid. Clin. Chem. 56: 1007-1014, 2010.

- ↑ Huestis MA, Scheidweiler KB, Saito T, Fortner N, Abraham T, Gustafson RA, Smith ML. Excretion of delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol in sweat. Forensic Sci. Int. 174:173-177, 2008.

- ↑ AlterNet, 28 July 2010, Has the Most Common Marijuana Test Resulted in Tens of Thousands of Wrongful Convictions?

- ↑ Lundin, Leigh (2009-03-01). "The Great Smoke-Out". Criminal Brief. http://www.criminalbrief.com/?p=5445.

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 "RAND study casts doubt on claims that marijuana acts as "gateway" to the use of cocaine and heroin". RAND Corporation. 2002-12-02. http://www.rand.org/news/press.02/gateway.html.

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 Torabi MR, Bailey WJ, Majd-Jabbari M (1993). "Cigarette Smoking as a Predictor of Alcohol and Other Drug Use by Children and Adolescents: Evidence of the "Gateway Drug Effect"". The Journal of School Health 63 (7): 302–306. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.1993.tb06150.x. PMID 8246462.

- ↑ Australian Government Department of Health: National Cannabis Strategy Consultation Paper, p. 4. "Cannabis has been described as a 'Trojan Horse' for nicotine addiction, given the usual method of mixing Cannabis with tobacco when preparing marijuana for administration."

- ↑ Hall WD, Lynskey M (January 2005). "Is Cannabis A Gateway Drug? Testing Hypotheses About the Relationship Between Cannabis Use and the Use of Other Illicit Drugs.". Drug and Alcohol Review 24 (1): 39–48. doi:10.1080/09595230500126698. PMID 16191720. http://www.informaworld.com/openurl?genre=article&doi=10.1080/09595230500126698&magic=pubmed||1B69BA326FFE69C3F0A8F227DF8201D0.

- ↑ Saitz, Richard (2003-02-18). "Is marijuana a gateway drug?". Journal Watch. http://general-medicine.jwatch.org/cgi/content/full/2003/218/1.

- ↑ Degenhardt, Louisa et al. (2007). "Who are the new amphetamine users? A 10-year prospective study of young Australians". http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01906.x.

- ↑ Morral AR, McCaffrey DF, Paddock SM (2002). "Reassessing the marijuana gateway effect". Addiction 97 (12): 1493–504. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00280.x. PMID 12472629. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/118957921/abstract.

- ↑ "Marijuana Policy Project- FAQ". http://www.mpp.org/about/faq.html.

- ↑ Many Dutch coffee shops close as liberal policies change, Exaptica, 27/11/2007.

- ↑ EMCDDA Cannabis reader: Global issues and local experiences, Perspectives on Cannabis controversies, treatment and regulation in Europe, 2008, p. 157.

- ↑ 43 Amsterdam coffee shops to close door, Radio Netherlands, Friday 21 November 2008.

- ↑ UNODC.org

- ↑ "Report on U.S. Domestic Marijuana Production". NORML. http://norml.org/index.cfm?Group_ID=4444. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ↑ "Marijuana Crop Reports". NORML. http://norml.org/index.cfm?Group_ID=4414. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ↑ "Marijuana Called Top U.S. Cash Crop". 2008 ABCNews Internet Ventures. http://abcnews.go.com/business/story?id=2735017&page=1.

- ↑ United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2008) (PDF). World drug report. United Nations Publications. p. 264. ISBN 978-92-1-148229-4. http://www.unodc.org/documents/wdr/WDR_2008/WDR_2008_eng_web.pdf.

- ↑ European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2008) (PDF). Annual report: the state of the drugs problem in Europe. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. p. 38. ISBN 978-92-9168-324-6. http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/attachements.cfm/att_64227_EN_EMCDDA_AR08_en.pdf.

- ↑ Dearne Safer Neighbourhood Team (SNT) recovers cannabis with a street value of approximately £9,000

- ↑ 119.0 119.1 Cockburn, Alexander; Jeffrey St. Clair (1998). Whiteout: The CIA, Drugs and the Press. Verso. pp. 117–118. ISBN 1859841392. http://books.google.com/?id=s5qIj_h_PtkC&printsec=frontcover#PPA118,M1.

- ↑ Daniel Forbes (November 19, 2002). "The Myth of Potent Pot". Slate.com. http://www.slate.com/id/2074151.

- ↑ "World Drug Report 2006". United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/WDR-2006.html. Ch. 2.3.

- ↑ "High-potency cannabis and the risk of psychosis - Di Forti et al. 195 (6): 488 - The British Journal of Psychiatry". Bjp.rcpsych.org. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.109.064220. http://bjp.rcpsych.org/cgi/content/abstract/195/6/488. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ↑ BBC: Cannabis laws to be strengthened. May 2008 20:55 UK.

- ↑ "Dutch-Passion - Power Plant ®, Powerplant (mostly Sativa) was developed in 1997 from new South African genetics.". Cgi.dutch-passion.nl. http://cgi.dutch-passion.nl/index.php?p=seeds&grow=1. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ↑ Tj. T. Mensinga et al.. "A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Cross-Over Study on the Pharmacokinetics and Effects of Cannabis." (PDF). RIVM. http://www.rivm.nl/bibliotheek/rapporten/267002002.pdf.

- ↑ Curran H.V., et al. (2002). "Cognitive and subjective dose-response effects". NCBI. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=12373420&dopt=AbstractCurranCurran.

- ↑ "Marijuana Dictionary". http://www.marijuanadictionary.com/.

Further reading

- Booth, Martin (2005). Cannabis: A History. Macmillan Publishers & Random House, Inc. ISBN 978-0-312-42494-7. http://books.google.com/?id=O7AoY6ljSygC&printsec=frontcover.

External links

- Wiktionary Appendix of Cannabis Slang

- "Cannabis: a health perspective and research agenda", Programme on Substance Abuse, World Health Organization, 1997

- Erowid Cannabis (Marijuana) Vault

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||