Lymphoma

| Lymphoma | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

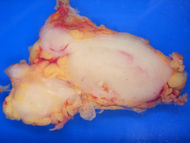

Follicular lymphoma replacing a lymph node |

|

| ICD-10 | C81.-C96. |

| ICD-O: | 9590-9999 |

| MeSH | D008223 |

Lymphoma is a cancer that begins in the lymphatic cells of the immune system and presents as a solid tumor of lymphoid cells. It is treatable with chemotherapy, and in some cases radiotherapy and/or bone marrow transplantation, and can be curable depending on the histology, type, and stage of the disease.[1] These malignant cells often originate in lymph nodes, presenting as an enlargement of the node (a tumor). Lymphomas are closely related to lymphoid leukemias, which also originate in lymphocytes but typically involve only circulating blood and the bone marrow (where blood cells are generated in a process termed haematopoesis) and do not usually form static tumors.[1] There are many types of lymphomas, and in turn, lymphomas are a part of the broad group of diseases called hematological neoplasms.

Thomas Hodgkin published the first description of lymphoma in 1832, specifically of the form named after him, Hodgkin's lymphoma.[2] Since then, many other forms of lymphoma have been described, grouped under several proposed classifications. The 1982 Working formulation classification became very popular. It introduced the category non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), divided into 16 different diseases. However, because these different lymphomas have little in common with each other, the NHL label is of limited usefulness for doctors or patients and is slowly being abandoned. The latest classification by the WHO (2001) lists 43 different forms of lymphoma divided in four broad groups.

Although older classifications referred to histiocytic lymphomas, these are recognized in newer classifications as of B, T or NK cell lineage. True histiocytic malignancies are rare and are classified as sarcomas.[3]

Contents |

Classification

A number of various different classification systems exist for lymphoma. As an alternative to the American Lukes-Butler classification, in the early 1970s, Karl Lennert of Kiel, Germany, proposed a new system of classifying lymphomas based on cellular morphology and their relationship to cells of the normal peripheral lymphoid system.[4]

Some forms of lymphoma are categorized as indolent (e.g. small lymphocytic lymphoma), compatible with a long life even without treatment, whereas other forms are aggressive (e.g. Burkitt's lymphoma), causing rapid deterioration and death. However, most of the aggressive lymphomas respond well to treatment and are curable. The prognosis therefore depends on the correct classification of the disease, established by a pathologist after examination of a biopsy.[5]

Working Formulation and Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

The 1982 Working Formulation is a classification of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It excluded the Hodgkin lymphomas and divided the remaining lymphomas into four grades (Low, Intermediate, High, and Miscellaneous) related to prognosis, with some further subdivisions based on the size and shape of affected cells. This purely histological classification included no information about cell surface markers, or genetics, and it made no distinction between T-cell lymphomas or B-cell lymphomas.

The Working Formulation was widely accepted at the time of its publication but is now obsolete. [6] It was superseded by subsequent classifications (see below) but it is still used by cancer agencies for compilation of lymphoma statistics and historical comparisons.

REAL

In the mid 1990s,the Revised European-American Lymphoma (REAL) Classification attempted to apply immunophenotypic and genetic features in identifying distinct clinicopathologic entities among all the lymphomas except Hodgkin's lymphoma.[7] REAL has been superseded by the WHO classification.

World Health Organization (WHO)

The WHO Classification, published in 2001 and updated in 2008,[3] is the latest classification of lymphoma and is based upon the foundations laid within the "Revised European-American Lymphoma classification" (REAL). This system attempts to group lymphomas by cell type (i.e. the normal cell type that most resembles the tumor) and defining phenotypic, molecular or cytogenetic characteristics. There are three large groups: the B cell, T cell, and natural killer cell tumors. Other less common groups, are also recognized. Hodgkin's lymphoma, although considered separately within the World Health Organization (and preceding) classifications, is now recognized as being a tumor of, albeit markedly abnormal, lymphocytes of mature B cell lineage.

Mature B cell neoplasms

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia/Small lymphocytic lymphoma

- B-cell prolymphocytic leukemia

- Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (such as Waldenström macroglobulinemia)

- Splenic marginal zone lymphoma

- Plasma cell neoplasms:

- Plasma cell myeloma

- Plasmacytoma

- Monoclonal immunoglobulin deposition diseases

- Heavy chain diseases

- Extranodal marginal zone B cell lymphoma, also called MALT lymphoma

- Nodal marginal zone B cell lymphoma (NMZL)

- Follicular lymphoma

- Mantle cell lymphoma

- Diffuse large B cell lymphoma

- Mediastinal (thymic) large B cell lymphoma

- Intravascular large B cell lymphoma

- Primary effusion lymphoma

- Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia

Mature T cell and natural killer (NK) cell neoplasms

- T cell prolymphocytic leukemia

- T cell large granular lymphocytic leukemia

- Aggressive NK cell leukemia

- Adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma

- Extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma, nasal type

- Enteropathy-type T cell lymphoma

- Hepatosplenic T cell lymphoma

- Blastic NK cell lymphoma

- Mycosis fungoides / Sezary syndrome

- Primary cutaneous CD30-positive T cell lymphoproliferative disorders

- Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma

- Lymphomatoid papulosis

- Angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma

- Peripheral T cell lymphoma, unspecified

- Anaplastic large cell lymphoma

Hodgkin lymphoma

- Classical Hodgkin lymphomas:

- Nodular sclerosis

- Mixed cellularity

- Lymphocyte-rich

- Lymphocyte depleted or not depleted

- Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma

Immunodeficiency-associated lymphoproliferative disorders

- Associated with a primary immune disorder

- Associated with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)

- Post-transplant

- Associated with methotrexate therapy

- Primary central nervous system lymphoma occurs most often in immunocomprimised patients,in particular those with AIDS,but it can occur in the immunocompetent as well.It has a poor prognosis,particularly in those with AIDS.Treatment can consist of corticosteroids, radiotherapy,and chemotherapy,often with methotrexate.

Other classification systems

Symptoms

- Anorexia

- Dyspnea

- Fatigue[8]

- Fever of unknown origin

- Lymphadenopathy

- Night sweats

- Pruritus

- Weight loss

Diagnosis, etiology, staging, prognosis, and treatment

| 5-year relative survival by stage at diagnosis[9] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Stage at diagnosis | 5-year relative survival (%) |

Percentage of cases (%) |

| Distant (cancer has metastasized) | 59.9 | 45 |

| Localized (confined to primary site) | 82.1 | 28 |

| Regional (spread to regional lymphnodes) | 77.5 | 19 |

| Unknown (unstaged) | 67.5 | 8 |

These depend on the specific form of lymphoma.[10] For some forms of lymphoma, watchful waiting is often the initial course of action.[11] If a low-grade lymphoma is becoming symptomatic, radiotherapy or chemotherapy are the treatments of choice, although they do not cure the lymphoma, they can alleviate the symptoms, particularly painful lymphadenopathy. Patients with these types of lymphoma can live near-normal lifespans, but the disease is incurable. Treatment of some other, more aggressive, forms of lymphoma can result in a cure in the majority of cases, but the prognosis for patients with a poor response to therapy is worse.[12] Treatment for these types of lymphoma typically consists of aggressive chemotherapy, including the CHOP regimen. Hodgkin lymphoma typically is treated with radiotherapy alone, as long as it is localized.[13] Advanced Hodgkins disease requires systemic chemotherapy, sometimes combined with radiotherapy.[14] See the articles on the corresponding form of lymphoma for further information.

Epidemiology

Lymphoma is the most common form of hematological malignancy, or "blood cancer", in the developed world.

Taken together, lymphomas represent 5.3% of all cancers (excluding simple basal cell and squamous cell skin cancers) in the United States and 55.6% of all blood cancers.[16]

According to the U.S. National Institutes of Health, lymphomas account for about five percent of all cases of cancer in the United States, and Hodgkin's lymphoma in particular accounts for less than one percent of all cases of cancer in the United States.

Because the whole system is part of the body's immune system, patients with a weakened immune system such as from HIV infection or from certain drugs or medication also have a higher incidence of lymphoma.

Comparison

Following is a comparison of the most common types of lymphoma:

| Lymphoma type | Relative incidence | Histopathology | Cell markers | Overall 5-year survival |

Other comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precursor T-cell leukemia/lymphoma | 40% of lymphomas in childhood.[17] | Lymphoblasts with irregular nuclear contours, condensed chromatin, small nucleoli and scant cytoplasm without granules.[17] | TdT, CD2, CD7[17] | It often presents as a mediastinal mass because of involvement of the thymus.[17] It is highly associated with NOTCH1 mutations.[17] Most common in adolescent males.[17] | |

| Follicular lymphoma | 40% of lymphomas in adults[17] | Small "cleaved" cells (centrocytes) mixed with large activated cells (centroblasts). Usually nodular ("follicular") growth pattern[17] | CD10, surface Ig[17] | 72-77%[18] | Occurs in older adults. Usually involves lymph nodes, bone marrow and spleen.[17] Associated with t(14;18) translocation overexpressing Bcl-2.[17] Indolent[17] |

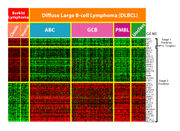

| Diffuse large B cell lymphoma | 40 to 50% of lymphomas in adults[17] | Variable. Most resemble B cells of large germinal centers. Diffuse growth pattern.[17] | Variable expression of CD10 and surface Ig[17] | 60%[19] | Occurs in all ages, but most commonly in older adults. Often occurs outside lymph nodes. Aggressive.[17] |

| Mantle cell lymphoma | 3 to 4% of lymphomas in adults[17] | Lymphocytes of small to internediate size growing in diffuse pattern[17] | CD5[17] | 50%[20] to 70%[20] | Occurs mainly in adult males. Usually involves lymph nodes, bone marrow, spleen and GI tract. Associated with t(11;14) translocation overexpressing cyclin D1. Moderately aggressive.[17] |

| B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia/lymphoma | 3 to 4 % of lymphomas in adults[17] | Small resting lymphocytes mixed with variable number of large activated cells. Lymph nodes are diffusely effaced[17] | CD5, surface immunoglobulin[17] | 50%.[21] | Occurs in older adults. Usually involves lymph nodes, bone marrow and spleen. Most patients have peripheral blood involvement. Indolent.[17] |

| MALT lymphoma | ~5% of lymphomas in adults[17] | Variable cell size and differentiation. 40% show plasma cell differentiation. Homing of B cells to epithelium creates lymphoepithelial lesions.[17] | CD5, CD10, surface Ig[17] | Frequently occurs outside lymph nodes. Very indolent. May be cured by local excision.[17] | |

| Burkitt's lymphoma | < 1% of lymphomas in the United States[17] | Round lymphoid cells of intermediate size with several nucleoli. Starry-sky appearance by diffuse spread with interspersed apoptosis.[17] | CD10, surface Ig[17] | 50%[22] | Endemic in Africa, sporadic elsewhere. More common in immunocompromised and in children. Often visceral involvement. Highly aggressive.[17] |

| Mycosis fungoides | Most common cutaneous lymphoid malignancy | Usually small lymphoid cells with convoluted nuclei that often infiltrate the epidermis, creating Pautier microabscesses[17] | CD4[17] | 75%[23] | Localized or more generalized skin symptoms. Generally indolent. In a more aggressive variant, [17]Sézary's disease, there is skin erythema and peripheral blood involvement.[17] |

| Peripheral T-cell lymphoma-Not-Otherwise-Specified | Most common T cell lymphoma [17] | Variable. Usually a mix small to large lymphoid cells with irregular nuclear contours.[17] | CD3[17] | Probably consists of several rare tumor types. It is often disseminated and generally aggressive.[17] | |

| Nodular sclerosis form of Hodgkin lymphoma | Most common type of Hodgkin's lymphoma[17] | Reed-Sternberg cell variants and inflammation. usually broad sclerotic bands that consists of collagen.[17] | CD15, CD30[17] | Most common in young adults. It often arises in the mediastinum or cervical lymph nodes.[17] | |

| Mixed-cellularity subtype of Hodgkin lymphoma | Second most common form of Hodgkin's lymphoma[17] | Many classic Reed-Sternberg cells and inflammation[17] | CD15, CD30[17] | Most common in men. More likely to be diagnosed at advanced stages than the nodular sclerosis form. Epstein-Barr virus involved in 70% of cases.[17] |

See also

- BCP-1 cells

- Ann Arbor staging

- International Prognostic Index

- Epstein barr virus

- Lymphadenopathy

- Chemotherapy regimens

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Parham, Peter (2005). The immune system. New York: Garland Science. p. 414. ISBN 0-8153-4093-1.

- ↑ Hellman, Samuel; Mauch, P.M. Ed. (1999). Hodgkin's Disease. Chapter 1: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 5. ISBN 0-7817-1502-4.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 ed. by Elaine S. Jaffe .... (2001). Pathology and Genetics of Haemo (World Health Organization Classification of tumors S.). Oxford Univ Pr. ISBN 92-832-2411-6.

- ↑ Lennert, Karl; Feller, Alfred C.; Jacques Diebold; M. Paulli; A. Le Tourneau (2002). Histopathology of Non-Hodgkin's Lymphomas (Based on the Updated Kiel Classification). Berlin: Springer. pp. 2. ISBN 3-540-63801-6.

- ↑ Wagman LD. "Principles of Surgical Oncology" in Pazdur R, Wagman LD, Camphausen KA, Hoskins WJ (Eds) Cancer Management: A Multidisciplinary Approach. 11 ed. 2008.

- ↑ Clarke CA, Glaser SL, Dorfman RF, Bracci PM, Eberle E, Holly EA (January 2004). "Expert review of non-Hodgkin lymphomas in a population-based cancer registry: reliability of diagnosis and subtype classifications". Cancer Epidemiol. Bio-markers Prev. 13 (1): 138–43. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-03-0250. PMID 14744745.

- ↑ www.emedicine.com on Lymphoma, Non-Hodgkin

- ↑ http://lymphoma.about.com/od/symptoms/tp/warningsigns.htm

- ↑ [1] Data from the USA 1999-2006, All Races, Both Sexes: Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Waldron W, Ruhl J, Howlader N, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, Mariotto A, Eisner MP, Lewis DR, Cronin K, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Stinchcomb DG, Edwards BK (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2007, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2007/, based on November 2009 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, 2010.

- ↑ Sweetenham JW (November 2009). "Treatment of lymphoblastic lymphoma in adults". Oncology (Williston Park, N.Y.) 23 (12): 1015–20. PMID 20017283.

- ↑ Elphee EE (May 2008). "Understanding the concept of uncertainty in patients with indolent lymphoma". Oncol Nurs Forum 35 (3): 449–54. doi:10.1188/08.ONF.449-454. PMID 18467294.

- ↑ Bernstein SH, Burack WR (2009). "The incidence, natural history, biology, and treatment of transformed lymphomas". Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2009: 532–41. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2009.1.532. PMID 20008238.

- ↑ Martin NE, Ng AK (November 2009). "Good things come in small packages: low-dose radiation as palliation for indolent non-Hodgkin lymphomas". Leuk. Lymphoma 50 (11): 1765–72. doi:10.3109/10428190903186510. PMID 19883306.

- ↑ Kuruvilla J (2009). "Standard therapy of advanced Hodgkin lymphoma". Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2009: 497–506. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2009.1.497. PMID 20008235.

- ↑ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates_country/en/index.html. Retrieved Nov. 11, 2009.

- ↑ Horner MJ, Ries LAG, Krapcho M, Neyman N, et al. (eds).. "SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2006". Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER). Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2006/. Retrieved 03 November 2009. "Table 1.4: Age-Adjusted SEER Incidence and U.S. Death Rates and 5-Year Relative Survival Rates By Primary Cancer Site, Sex and Time Period"

- ↑ 17.00 17.01 17.02 17.03 17.04 17.05 17.06 17.07 17.08 17.09 17.10 17.11 17.12 17.13 17.14 17.15 17.16 17.17 17.18 17.19 17.20 17.21 17.22 17.23 17.24 17.25 17.26 17.27 17.28 17.29 17.30 17.31 17.32 17.33 17.34 17.35 17.36 17.37 17.38 17.39 17.40 17.41 17.42 17.43 17.44 17.45 17.46 17.47 Table 12-8 with lymphomas sorted out. Mitchell, Richard Sheppard; Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson. Robbins Basic Pathology. Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 1-4160-2973-7. 8th edition.

- ↑ eMedicine Specialties > Lymphoma, Follicular Author: Cesar O Freytes. Coauthor: Julianna A Burzynski. Updated: Nov 3, 2009

- ↑ Turgeon, Mary Louise (2005). Clinical hematology: theory and procedures. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 285–286. ISBN 0-7817-5007-5.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1

- 50% for limited stage, according to: Leitch HA, Gascoyne RD, Chhanabhai M, Voss NJ, Klasa R, Connors JM (October 2003). "Limited-stage mantle-cell lymphoma". Ann. Oncol. 14 (10): 1555–61. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdg414. PMID 14504058.

- 70% for advanced stage, according to most recent values in: Herrmann A, Hoster E, Zwingers T, et al. (February 2009). "Improvement of overall survival in advanced stage mantle cell lymphoma". J. Clin. Oncol. 27 (4): 511–8. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.16.8435. PMID 19075279.

- ↑ The Merck Manual of Geriatrics > Chronic Leukemias Retrieved June, 2010

- ↑ Diviné M, Casassus P, Koscielny S, et al. (December 2005). "Burkitt lymphoma in adults: a prospective study of 72 patients treated with an adapted pediatric LMB protocol". Ann. Oncol. 16 (12): 1928–35. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdi403. PMID 16284057.

- ↑ Kirova YM, Piedbois Y, Haddad E, et al. (May 1999). "Radiotherapy in the management of mycosis fungoides: indications, results, prognosis. Twenty years experience". Radiother Oncol 51 (2): 147–51. doi:10.1016/S0167-8140(99)00050-X. PMID 10435806.

External links

- Timeline of discovery and treatment of Hodgkin's Lymphoma

- US lymphoma statistics from the United States National Cancer Institute

- Hodgkin Lymphoma and UK Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma statistics from the UK

- Latest news and research on Lymphoma

- Lymphoma Imaging Appearance - Chest Radiography

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||