Luddite

The Luddites were a social movement of British textile artisans in the nineteenth century who protested – often by destroying mechanised looms – against the changes produced by the Industrial Revolution, which they felt was leaving them without work and changing their way of life. It took its name from Ned Ludd.

The movement emerged in the harsh economic climate of the Napoleonic Wars and difficult working conditions in the new textile factories. The principal objection of the Luddites was to the introduction of new wide-framed automated looms that could be operated by cheap, relatively unskilled labour, resulting in the loss of jobs for many skilled textile workers. The movement began in 1811 and 1812, when mills and pieces of factory machinery were burned by handloom weavers, and for a short time was so strong that Luddites clashed in battles with the British Army. Measures taken by the British government to suppress the movement included a mass trial at York in 1812 that resulted in many executions and penal transportations.

The action of destroying new machines had a long tradition before the Luddites, especially within the textile industry. Many inventors of the 18th century were attacked by vested interests who were threatened by new and more efficient ways of making yarn and cloth. Samuel Crompton, for example, had to hide his new spinning mule in the roof of his house at Hall i' th' Wood in 1779 to prevent it being destroyed by the mob.

In modern usage, "Luddite" is a term describing those opposed to industrialisation, automation, computerisation or new technologies in general.[1]

Contents |

History

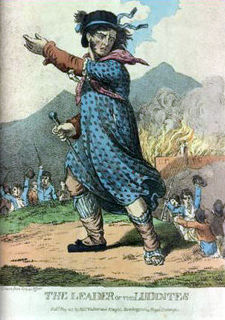

The original Luddites claimed to be led by one "King Ludd" (also known as "General Ludd" or "Captain Ludd") whose signature appears on a "workers' manifesto" of the time. King Ludd was based on the earlier Ned Ludd, who some believed to have destroyed two large stocking frames in the village of Anstey, Leicestershire in 1779. At that time in England, machine breaking could lead to heavy penalties or even execution, which might have led some to use fictitious names for protection.

Research by historian Kevin Binfield[2] is particularly useful in placing the Luddite movement in historical context – as organised action by stockingers had occurred at various times since 1675, and the present action had to be seen in the context of the hardships suffered by the working class during the Napoleonic Wars.

The movement began in Nottingham in 1811 and spread rapidly throughout England in 1811 and 1812. Many wool and cotton mills were destroyed until the British government suppressed the movement. The Luddites met at night on the moors surrounding the industrial towns, practising drills and manoeuvres, and often enjoyed local support. The main areas of the disturbances were Nottinghamshire in November 1811, followed by the West Riding of Yorkshire in early 1812 and Lancashire from March 1813. Battles between Luddites and the military occurred at Burton's Mill in Middleton, and at Westhoughton Mill, both in Lancashire. It was rumoured at the time that agents provocateurs employed by the magistrates were involved in provoking the attacks. Magistrates and food merchants were also objects of death threats and attacks by the anonymous King Ludd and his supporters. Some industrialists even had secret chambers constructed in their buildings, which may have been used as hiding places.[3]

"Machine breaking" (industrial sabotage) was subsequently made a capital crime by the Frame Breaking Act[4] – legislation which was opposed by Lord Byron, one of the few prominent defenders of the Luddites – and 17 men were executed after an 1813 trial in York. Many others were transported as prisoners to Australia. At one time, there were more British troops fighting the Luddites than Napoleon I on the Iberian Peninsula.[5] Three Luddites, led by George Mellor, ambushed and assassinated a mill-owner (William Horsfall from Ottiwells Mill in Marsden) at Crosland Moor, Huddersfield, Mellor firing the shot to the groin which would, soon enough, prove fatal. Horsfall had remarked previously that he would "Ride up to his saddle in Luddite blood". The Luddites responsible were hanged in York, and shortly thereafter "Luddism" began to wane.

However, the movement can also be seen as part of a rising tide of English working-class discontent in the early 19th century (see also, for example, the Pentrich Rising of 1817, which was a general uprising, but led by an unemployed Nottingham stockinger, and probable ex-Luddite, Jeremiah Brandreth.) An agricultural variant of Luddism, centering on the breaking of threshing machines, was crucial to the widespread Swing Riots of 1830 in southern and eastern England.

In recent years, the terms Luddism and Luddite or neo-Luddism and neo-Luddite have become synonymous with anyone who opposes the advance of technology due to the cultural and socioeconomic changes that are associated with it.

Many of the ideas that were encompassed within the Luddite Movement have been studied and evaluated in modern economics literature. The concept of "Skill Biased Technological Change" (SBTC) posits that technology contributes to the de-skilling of routine, manual tasks.[6]

Criticism

The term "Luddite fallacy" has become a concept in neoclassical economics reflecting the belief that labour-saving technologies (i.e., technologies that increase output-per-worker) increase unemployment by reducing demand for labour. Neoclassical economists believe this argument is fallacious because they assert that instead of seeking to keep production constant by employing a smaller and more productive workforce, employers increase production while keeping workforce size constant.[7]

In his work on English history, The Making of the English Working Class, E. P. Thompson presented an alternative view of Luddite history. He argues that Luddites were not opposed to new technology in itself, but rather to the abolition of set prices and therefore also to the introduction of the free market.

Thompson argues that it was the newly-introduced economic system against which the Luddites were protesting. Thompson cites the many historical accounts of Luddite raids on workshops where some frames were smashed whilst others (whose owners were obeying the old economic practice and not trying to cut prices) were left untouched. This would clearly distinguish the Luddites from someone who was today called a luddite; whereas today a luddite would reject new technology because it is new, the Luddites were acting from a sense of self-preservation rather than merely fear of change.

In popular culture

- Shirley by Charlotte Brontë, is a social novel set against the backdrop of the Luddite riots in the Yorkshire textile industry in 1811–1812.

- The Difference Engine by William Gibson and Bruce Sterling, is a novel speculating on what might have been, had Charles Babbage completed his Difference Engine during the Industrial Revolution.

- The Luddites are called "Monkey Luddites" in Scott Westerfeld's novel Leviathan. Instead of opposing machinery, they are British and French people who oppose the genetic engineering employed by the Darwinists. They fear and condemn fabricated animals on moral grounds, believing their creation to be blasphemous and against nature.

- In "The Cloud Walker" by Edmund Cooper, a post-apocalyptic Britain is under the control of the Luddite Church, which bans all mechanical technology. Their symbol is a silver hammer.

- "The Triumph of General Ludd" – Roy Palmer in "Touch on the Times: Songs of Social Change 1770 to 1914" (ISBN 0140811826) says that this is a ballad that has been preserved in manuscript in the Home Office papers. Palmer sets it to the tune "Poor Jack", written by Charles Dibden. It was recorded by Chumbawamba on their album English Rebel Songs 1381–1984.

See also

|

|

References

Notes

- ↑ "Luddite" Compact Oxford English Dictionary at AskOxford.com. Accessed February 22, 2010.

- ↑ "Luddites and Luddism" extract from Binfield, Kevin ed., Writings of the Luddites Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004. Accessed 4 June 2008.

- ↑ "Workmen discover secret chambers". BBC News. 2006-08-15. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/leicestershire/4791069.stm. Retrieved 2010-05-11.

- ↑ "Frame Breaking Act" at everything2.com

- ↑ Hobsbawm, Eric (1964) "The Machine Breakers" in Labouring Men. Studies in the History of Labour., London, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, page 6. Hobsbawm has popularized this comparison and refers to the original statement in Darvall, Frank Ongley (1969) Popular Disturbances and Public Order in Regency England, London, Oxford University Press, page 260.

- ↑ Autor, Frank; Levy, David and Murnane, Richard J. "The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: An Empirical Exploration" Quarterly Journal of Economics (2003)

- ↑ Easterly, William (2001). The Elusive Quest for Growth: Economists' Adventures and Misadventures in the Tropics. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. pp. 53–54. ISBN 0-262-55042-3.

Bibliography

- Bailey, Brian J., The Luddite Rebellion (1998), New York : New York University Press, ISBN 0-8147-1335-1.

- Binfield, Kevin. Writings of the Luddites, (2004), Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-7612-5

- Fox, Nicols. Against the Machine: The Hidden Luddite History in Literature, Art, and Individual Lives, (2003), Island Press ISBN 1-55963-860-5

- Hunt, Lynn, Thomas R. Martin, Barbara H. Rosenwein, R. Po-chia Hsia, and Bonnie G. Smith. The Making of the West. 3rd ed. Edited by Mary Dougherty. Vol. C of Since 1740. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2009.

- Jones, Steven E. Against Technology: From Luddites to Neo-Luddism, (2006) Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-97868-2

- Perlman, Fredy. Against His-tory, Against Leviathan, (1983) Black and Red, ISBN 0-934868-25-5

- Sale, Kirkpatrick. Rebels Against the Future: The Luddites and Their War on the Industrial Revolution, (1996) ISBN 0-201-40718-3

- Watson,David. Against the Megamachine: Essays on Empire and its Enemies, (1998) Autonomedia, ISBN 1-57027-087-2 .

External links

- On-line Luddism Index

- Is it O.K. to be a Luddite? by Thomas Pynchon

- Luddism and the Neo-Luddite Reaction by Martin Ryder, University of Colorado at Denver School of Education

- CBC program Ideas on Luddites

- Extracts from Kevin Binfield's book.

- Luddites Stan Iverson Memorial Archives (articles, links & timeline)

- Historical reports and accounts on key events concerning the Luddite movement hosted by Marxists.org

- The Luddites and the Combination Acts from the Marxists Internet Archive

- Luddite Wines in South Africa make only a Shiraz wine in true Luddite style

- Luddites and Luddism (Kevin Binfield, ed.)