Werewolf

A werewolf, also known as a lycanthrope (from the Greek λυκάνθρωπος: λύκος, lukos, "wolf", and άνθρωπος, anthrōpos, man), is a mythological or folkloric human with the ability to shapeshift into an anthropomorphic wolf-like creature, either purposely, by being bitten by another werewolf, or after being placed under a curse. This transformation is often associated with the appearance of the full moon, as popularly noted by the medieval chronicler Gervase of Tilbury, and perhaps in earlier times among the ancient Greeks through the writings of Petronius.

Werewolves are often attributed superhuman strength and senses, far beyond those of both wolves and men. Though it is endowed with all the beastly implements like stout-jaws and offensive paws that a natural wolf is most likely to use during a conflict with its enemy or prey, it has been classically known to kill the others with a dagger or a knife though bite marks are also found on the (generally) dead victim [1]. The werewolf is generally held as a European character, although its lore spread through the world in later times. Shape-shifters, similar to werewolves, are common in tales from all over the world, most notably amongst the Native Americans, though most of them involve animal forms other than wolves.

Werewolves are a frequent subject of modern fictional books, although fictional werewolves have been attributed traits distinct from those of original folklore, most notably vulnerability to silver bullets. Werewolves continue to endure in modern culture and fiction, with books, films and television shows cementing the werewolf's stance as a dominant figure in horror.

Contents |

Etymology

The word werewolf is thought to derive from Old English wer (or were)— pronounced variously as /ˈwɛər, ˈwɪər, ˈwɜr/— and wulf. The first part, wer, translates as "man" (in the specific sense of male human, not the race of humanity generally). It has cognates in several Germanic languages including Gothic wair, Old High German wer, and Old Norse verr, as well as in other Indo-European languages, such as Sanskrit 'vira', Latin vir, Irish fear, Lithuanian vyras, and Welsh gŵr, which have the same meaning. The second half, wulf, is the ancestor of modern English "wolf"; in some cases it also had the general meaning "beast."

An alternative etymology derives the first part from Old English weri (to wear); the full form in this case would be glossed as wearer of wolf skin. Related to this interpretation is Old Norse ulfhednar, which denoted lupine equivalents of the berserker, said to wear a bearskin in battle.

Yet other sources derive the word from warg-wolf, where warg (or later werg and wero) is cognate with Old Norse vargr, meaning "rogue," "outlaw," or, euphemistically, "wolf".[2] A Vargulf was the kind of wolf that slaughtered many members of a flock or herd but ate little of the kill. This was a serious problem for herders, who had to somehow destroy the rogue wolf before it destroyed the entire flock or herd. The term Warg was used in Old English for this kind of wolf. Possibly related is the fact that, in Norse society, an outlaw (who could be murdered with no legal repercussions and was forbidden to receive aid) was typically called vargr, or "wolf."

Other terms

The term lycanthropy, referring both to the ability to transform oneself into a wolf and to the act of so doing, comes from Ancient Greek lykánthropos (λυκάνθρωπος): λύκος, lýkos ("wolf") + άνθρωπος, ánthrōpos ("human").[3] A compound of which "lyc-" derives from the Proto-Indo-European root *wlkwo-, meaning "wolf", formally denotes the "wolf - man" transformation. Lycanthropy is but one form of therianthropy, the ability to metamorphose into animals in general. The term therianthrope literally means "beast-man." The word has also been linked to the original werewolf of classical mythology, Lycaon, a king of Arcadia who, according to Ovid's Metamorphoses, was turned into a ravenous wolf in retribution for attempting to serve his own son to visiting Zeus in an attempt to disprove the god's divinity.

There is also a mental illness called lycanthropy in which a patient believes he or she is, or has transformed into, an animal and behaves accordingly. This is sometimes referred to as clinical lycanthropy to distinguish it from its use in legends. Despite its origin as a term for man-wolf transformations only, lycanthropy is used in this sense for animals of any type. This broader meaning is often used in modern fictional references, such as in roleplaying game culture.

Another ancient term for shapeshifting between any animal forms is versipellis, from which the English words turnskin and turncoat are derived.[4] This Latin word is similar in meaning as words used for werewolves and other shapeshifters in Russian (oboroten) and Old Norse (hamrammr).

The French name for a werewolf, sometimes used in English, is loup-garou (pronounced /lugaˈru/), from the Latin noun lupus meaning wolf.[5] The second element is thought to be from Old French garoul meaning "werewolf." This in turn is most likely from Frankish *wer-wulf meaning "man-wolf."[6]

Folk beliefs

Description and common attributes

Werewolves were said in European folklore to bear tell-tale physical traits even in their human form. These included the meeting of both eyebrows at the bridge of the nose, curved fingernails, low set ears and a swinging stride. One method of identifying a werewolf in its human form was to cut the flesh of the accused, under the pretense that fur would be seen within the wound. A Russian superstition recalls a werewolf can be recognised by bristles under the tongue.[7] The appearance of a werewolf in its animal form varies from culture to culture, though they are most commonly portrayed as being indistinguishable from ordinary wolves save for the fact that they have no tail (a trait thought characteristic of witches in animal form), and that they retain human eyes and voice. After returning to their human forms, werewolves are usually documented as becoming weak, debilitated and undergoing painful nervous depression.[7] Many historical werewolves were written to have suffered severe melancholia and manic depression, being bitterly conscious of their crimes.[7] One universally reviled trait in medieval Europe was the werewolf's habit of devouring recently buried corpses, a trait which is documented extensively, particularly in the Annales Medico-psychologiques in the 19th century.[7] Fennoscandian werewolves were usually old women who possessed poison coated claws and had the ability to paralyse cattle and children with their gaze.[7] Serbian vulkodlaks traditionally had the habit of congregating annually in the winter months, where they would strip off their wolf skins and hang them from trees. They would then get a hold of another vulkodlaks skin and burn it, releasing the vulkodlak from whom the skin came from its curse.[7] The Haitian jé-rouges typically try to trick mothers into giving away their children voluntarily by waking them at night and asking their permission to take their child, to which the disoriented mother may either reply yes or no.[7]

Becoming a werewolf

Various methods for becoming a werewolf have been reported, one of the simplest being the removal of clothing and putting on a belt made of wolfskin, probably as a substitute for the assumption of an entire animal skin (which also is frequently described).[8] In other cases, the body is rubbed with a magic salve.[8] To drink rainwater out of the footprint of the animal in question or to drink from certain enchanted streams were also considered effectual modes of accomplishing metamorphosis.[9] The 16th century Swedish writer Olaus Magnus says that the Livonian werewolves were initiated by draining a cup of specially prepared beer and repeating a set formula. Ralston in his Songs of the Russian People gives the form of incantation still familiar in Russia.

In Italy, France and Germany, it was said that a man could turn into a werewolf if he, on a certain Wednesday or Friday, slept outside on a summer night with the full moon shining directly on his face.[7]

In other cases, the transformation was supposedly accomplished by Satanic allegiance for the most loathsome ends, often for the sake of sating a craving for human flesh. "The werewolves", writes Richard Verstegan (Restitution of Decayed Intelligence, 1628),

are certayne sorcerers, who having annoynted their bodies with an ointment which they make by the instinct of the devil, and putting on a certayne inchaunted girdle, does not only unto the view of others seem as wolves, but to their own thinking have both the shape and nature of wolves, so long as they wear the said girdle. And they do dispose themselves as very wolves, in worrying and killing, and most of humane creatures.

Such were the views about lycanthropy current throughout the continent of Europe when Verstegan wrote.

The phenomenon of repercussion, the power of animal metamorphosis, or of sending out a familiar, real or spiritual, as a messenger, and the supernormal powers conferred by association with such a familiar, are also attributed to the magician, male and female, all the world over; and witch superstitions are closely parallel to, if not identical with, lycanthropic beliefs, the occasional involuntary character of lycanthropy being almost the sole distinguishing feature. In another direction the phenomenon of repercussion is asserted to manifest itself in connection with the bush-soul of the West African and the nagual of Central America; but though there is no line of demarcation to be drawn on logical grounds, the assumed power of the magician and the intimate association of the bush-soul or the nagual with a human being are not termed lycanthropy. Nevertheless it will be well to touch on both these beliefs here.

The curse of lycanthropy was also considered by some scholars as being a divine punishment. Werewolf literature shows many examples of God or saints allegedly cursing those who invoked their wrath with werewolfism. Those who were excommunicated by the Roman Catholic Church were also said to become werewolves.[7]

The power of transforming others into wild beasts was attributed not only to malignant sorcerers, but to Christian saints as well. Omnes angeli, boni et Mali, ex virtute naturali habent potestatem transmutandi corpora nostra ("All angels, good and bad have the power of transmutating our bodies") was the dictum of St. Thomas Aquinas. St. Patrick was said to have transformed the Welsh king Vereticus into a wolf; Natalis supposedly cursed an illustrious Irish family whose members were each doomed to be a wolf for seven years. In other tales the divine agency is even more direct, while in Russia, again, men supposedly became werewolves when incurring the wrath of the Devil.

A notable exception to the association of Lycanthropy and the Devil, comes from a rare and lesser known account of an 80-year-old man named Thiess. In 1692, in Jurgenburg, Livonia, Thiess testified under oath that he and other werewolves were the Hounds of God.[10] He claimed they were warriors who went down into hell to do battle with witches and demons. Their efforts ensured that the Devil and his minions did not carry off the grain from local failed crops down to hell. Thiess was steadfast in his assertions, claiming that werewolves in Germany and Russia also did battle with the devil's minions in their own versions of hell, and insisted that when werewolves died, their souls were welcomed into heaven as reward for their service. Thiess was ultimately sentenced to ten lashes for Idolatry and superstitious belief.

A distinction is often made between voluntary and involuntary werewolves. The former are generally thought to have made a pact, usually with the Devil, and morph into werewolves at night to indulge in nefarious acts. Involuntary werewolves, on the other hand, are werewolves by an accident of birth or health. In some cultures, individuals born during a new moon or suffering from epilepsy were considered likely to be werewolves.

Becoming a werewolf simply by being bitten by another werewolf as a form of contagion is common in modern horror fiction, but this kind of transmission is rare in legend, unlike the case in vampirism.[7]

Even if the denotation of lycanthropy is limited to the wolf-metamorphosis of living human beings, the beliefs classed together under this head are far from uniform, and the term is somewhat capriciously applied. The transformation may be temporary or permanent; the were-animal may be the man himself metamorphosed; may be his double whose activity leaves the real man to all appearance unchanged; may be his soul, which goes forth seeking whom it may devour, leaving its body in a state of trance; or it may be no more than the messenger of the human being, a real animal or a familiar spirit, whose intimate connection with its owner is shown by the fact that any injury to it is believed, by a phenomenon known as repercussion, to cause a corresponding injury to the human being.

Vulnerabilities

Most modern fiction describes werewolves as vulnerable to silver weapons and highly resistant to other attacks. This feature does not appear in stories about werewolves before the 19th century. (The claim that the Beast of Gévaudan, an 18th century wolf or wolf-like creature, was shot by a silver bullet appears to have been introduced by novelists retelling the story from 1935 onwards and not in earlier versions.[11])

Unlike vampires, they are not generally thought to be harmed by religious artifacts such as crucifixes and holy water. In many countries, rye and mistletoe were considered effective safeguards against werewolf attacks. Mountain ash is also considered effective, with one Belgian superstition stating that no house was safe unless under the shade of a mountain ash.[7] In some legends, werewolves have an aversion to wolfsbane.

Remedies

Various methods have existed for removing the werewolf form. In antiquity, the Ancient Greeks and Romans believed in the power of exhaustion in curing people of lycanthropy. The victim would be subjected to long periods of physical activity in the hope of being purged of the malady. This practice stemmed from the fact that many alleged werewolves would be left feeling weak and debilitated after committing depredations.[7]

In medieval Europe, traditionally, there are three methods one can use to cure a victim of werewolfism; medicinally (usually via the use of wolfsbane), surgically or by exorcism. However, many of the cures advocated by medieval medical practitioners proved fatal to the patients. A Sicilian belief of Arabic origin holds that a werewolf can be cured of its ailment by striking it on the forehead or scalp with a knife. Another belief from the same culture involves the piercing of the werewolf's hands with nails. Sometimes, less extreme methods were used. In the German lowland of Schleswig-Holstein, a werewolf could be cured if one were to simply address it three times by its Christian name, while one Danish belief holds that simply scolding a werewolf will cure it.[7] Conversion to Christianity is also a common method of removing werewolfism in the medieval period. A devotion to St. Hubert has also been cited as both cure for and protection from lycanthropes.

Classical literature

Herodotus in his Histories[12] wrote that the Neuri, a tribe he places to the north-east of Scythia, were transformed into wolves once every nine years. These rituals were apparently meant to symbolise earthly regeneration and rebirth. Virgil was also familiar with human beings transforming into wolves.[13]

In Greek mythology, the story of Lycaon provides one of the earliest examples of a werewolf legend. According to one version, Lycaon was transformed into a wolf as a result of eating human flesh; one of those who were present at periodical sacrifice on Mount Lycæon was said to suffer a similar fate.

In Metamorphoses, the Roman poet Ovid vividly described stories of men who roamed the woods of Arcadia in the form of wolves.[14]

The Roman scholar Pliny the Elder, relates two tales of lycanthropy. Quoting Euanthes,[15] he mentions a man who hung his clothes on an ash tree and swam across an Arcadian lake, transforming him into a wolf. On the condition that he attacked no human being for nine years, he would be free to swim back across the lake to resume human form. Pliny also quotes Agriopas regarding a tale of a man who was turned into a wolf after tasting the entrails of a human child.

In the Latin work of prose, the Satyricon, written about 60 C.E. by Gaius Petronius Arbiter, one of the characters, Niceros, tells a story at a banquet about a friend who turned into a wolf (chs. 61-62). He describes the incident as follows, "When I look for my buddy I see he'd stripped and piled his clothes by the roadside...He pees in a circle round his clothes and then, just like that, turns into a wolf!...after he turned into a wolf he started howling and then ran off into the woods."[16]

European cultures

Many European countries and cultures influenced by them have stories of werewolves, including Albania (oik), Armenia (mardagayl), Croatia/Bosnia (vukodlak), France (loup-garou), Greece (λυκανθρωπος - lycanthropos), Spain (hombre lobo), Argentina (lobizon), Mexico (hombre lobo and nahual), Bulgaria (върколак - varkolak), Turkey (kurtadam), Czech Republic (vlkodlak), Slovakia (vlkolak), Serbia/Montenegro (вукодлак - vukodlak), Belarus (ваўкалак - vaukalak), Russia (оборотень - oboroten' ), Ukraine (вовкулака - vovkulaka and перевертень - pereverten' ), Poland (wilkołak), Romania (vârcolac, priculici), Macedonia (vrkolak), Slovenia (volkodlak), Scotland (werewolf, wulver), England (werewolf), Ireland (faoladh or conriocht), Wales (bleidd-ddyn), Germany (Werwolf), the Netherlands (weerwolf), Denmark/Sweden/Norway (Varulv), Norway/Iceland (kveld-ulf, varúlfur), Galicia (lobishome), Portugal/Brazil (lobisomem), Lithuania (vilkolakis and vilkatlakis), Latvia (vilkatis and vilkacis), Andorra/Catalonia (home llop), Hungary (Vérfarkas and Farkasember), Estonia (libahunt), Finland (ihmissusi and vironsusi), and Italy (lupo mannaro). In northern Europe, there are also tales about people changing into animals including bears, as well as wolves.

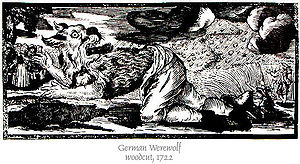

Werewolves in European tradition were mostly evil men who terrorized people in the form of wolves on command of the Devil, though there were rare narratives of people being transformed involuntarily. In the 10th century, they were given the binomial name of melancholia canina and in the 14th century, daemonium lupum.[7] In Marie de France's poem Bisclavret (c. 1200), the nobleman Bizuneh, for reasons not described in the lai, had to transform into a wolf every week. When his treacherous wife stole his clothing needed to restore his human form, he escaped the king's wolf hunt by imploring the king for mercy and accompanied the king thereafter. His behaviour at court was so much gentler than when his wife and her new husband appeared at court, that his hateful attack on the couple was deemed justly motivated, and the truth was revealed. Other tales of this sort include German fairy tales, Märchen, in which several aristocrats temporarily transform into beasts. See Snow White and Rose Red, where the tame bear is really a bewitched prince, and The Golden Bird where the talking fox is also a man.

Werewolf folklore is rare in England, possibly because wolves had been eradicated by authorities in the Anglo-Saxon period.[17]

Harald I of Norway is known to have had a body of Úlfhednar (wolf coated), which are mentioned in Vatnsdœla saga, Haraldskvæði, and the Völsunga saga resemble some werewolf legends. The Úlfhednar were fighters similar to the berserkers, though they dressed in wolf hides rather than those of bears and were reputed to channel the spirits of these animals to enhance effectiveness in battle.[7] These warriors were resistant to pain and killed viciously in battle, much like wild animals. Ulfhednar and berserkers are closely associated with the Norse god Odin.

In Latvian folklore, a vilkacis was someone who transformed into a wolf-like monster, which could be benevolent at times. Another collection of stories concern the skin-walkers. The vilkacis and skin-walkers probably have a common origin in Proto-Indo-European society, where a class of young unwed warriors were apparently associated with wolves.

In Hungarian folklore, the concept of werewolf goes back to the Middle Ages. The werewolves used to live specially in the region of Transdanubia, and it was thought that the ability to change into a wolf it was obtained in the infant age, after the suffering of abuse by the parents or by a curse. At the age of seven the boy leaves the house and goes hunting by night and can change to person or wolf whenever he wants. The curse can also be obtained when in the adulthood the person passed three times through an arch made of a Birch with the help of a wild rose's spine.

The werewolves were known to exterminate all kind of farm animals, especially sheep. The transformation usually occurred in the Winter solstice, Easter and full moon. Later in the XVII and XVIII century, the trials in Hungary not only were conduced against witches, but against werewolves too, and many records exist creating connections between both kinds. Also the vampires and werewolves are closely related in Hungary, being both feared in the antiquity.[18]

According to the first dictionary of modern Serbian language (published by Vuk Stefanović-Karadžić in 1818) vukodlak / вукодлак (werewolf) and vampir / вампир (vampire) are synonyms, meaning a man who returns from his grave for purposes of fornicating with his widow. The dictionary states this to be a common folk tale.

Common amongst the Kashubs of what is now northern Poland, and the Serbs and Slovenes, was the belief that if a child was born with hair, a birthmark or a caul on their head, they were supposed to possess shape-shifting abilities. Though capable of turning into any animal they wished, it was commonly believed that such people preferred to turn into a wolf.[19]

According to Armenian lore, there are women who, in consequence of deadly sins, are condemned to spend seven years in wolf form.[20] In a typical account, a condemned woman is visited by a wolfskin-toting spirit, who orders her to wear the skin, which causes her to acquire frightful cravings for human flesh soon after. With her better nature overcome, the she-wolf devours each of her own children, then her relatives' children in order of relationship, and finally the children of strangers. She wanders only at night, with doors and locks springing open at her approach. When morning arrives, she reverts to human form and removes her wolfskin. The transformation is generally said to be involuntary, but there are alternate versions involving voluntary metamorphosis, where the women can transform at will.

The 11th Century Belarusian Prince Usiaslau of Polatsk was considered to have been a Werewolf, capable of moving at superhuman speeds, as recounted in The Tale of Igor's Campaign: "Vseslav the prince judged men; as prince, he ruled towns; but at night he prowled in the guise of a wolf. From Kiev, prowling, he reached, before the cocks crew, Tmutorokan. The path of Great Sun, as a wolf, prowling, he crossed. For him in Polotsk they rang for matins early at St. Sophia the bells; but he heard the ringing in Kiev."

There were numerous reports of werewolf attacks – and consequent court trials – in 16th century France. In some of the cases there was clear evidence against the accused of murder and cannibalism, but none of association with wolves; in other cases people have been terrified by such creatures, such as that of Gilles Garnier in Dole in 1573, there was clear evidence against some wolf but none against the accused. The loup-garou eventually ceased to be regarded as a dangerous heretic and reverted to the pre-Christian notion of a "man-wolf-fiend." The lubins or lupins were usually female and shy in contrast to the aggressive loups-garous.

Some French werewolf lore is associated with documented events. The Beast of Gévaudan terrorized the general area of the former province of Gévaudan, now called Lozère, in south-central France. From the years 1764 to 1767, an unknown entity killed upwards of 80 men, women, and children. The creature was described as a giant wolf by the sole survivor of the attacks, which ceased after several wolves were killed in the area.

At the beginning of the 17th century witchcraft was prosecuted by James I of England, who regarded "warwoolfes" as victims of delusion induced by "a natural superabundance of melancholic."[21]

American cultures

During the Norse colonization of the Americas, it is thought by Woodward that the Vikings brought with them their beliefs in werewolves, which would manifest themselves in the folklore of some Native American tribes.[7]

The Naskapis believed that the caribou afterlife is guarded by giant wolves which kill careless hunters venturing too near. The Navajo people feared witches in wolf's clothing called "Mai-cob".[22]

When the European colonization of the Americas occurred, the pioneers brought their own werewolf folklore with them and were later influenced by the lore of their neighbouring colonies and those of the Natives. Belief in the loup-garou present in Canada, the Upper and Lower Peninsulas of Michigan[23] and upstate New York, originates from French folklore influenced by Native American stories on the Wendigo. In Mexico, there is a belief in a creature called the nahual, which traditionally limits itself to stealing cheese and raping women rather than murder. In Haiti, there is a superstition that werewolf spirits known locally as Jé-rouge (red eyes) can possess the bodies of unwitting persons and nightly transform them into cannibalistic lupine creatures.[7]

Origins of werewolf beliefs

Many authors have speculated that werewolf and vampire legends may have been used to explain serial killings in less rational ages . This theory is given credence by the tendency of some modern serial killers to indulge in practices commonly associated with werewolves, such as cannibalism, mutilation, and cyclic attacks. The idea is well explored in Sabine Baring-Gould's work The Book of Werewolves.

Until the 20th century, wolf attacks on humans were an occasional, but widespread feature of life in Europe.[24] Some scholars have suggested that it was inevitable that wolves, being the most feared predators in Europe, were projected into the folklore of evil shapeshifters. This is said to be corroborated by the fact that areas devoid of wolves typically use different kinds of predator to fill the niche; werehyenas in Africa, weretigers in India,[7] as well as werepumas ("runa uturuncu")[25][26] and werejaguars ("yaguaraté-abá" or "tigre-capiango")[27][28] of southern South America.

In his Man into Wolf (1948), anthropologist Robert Eisler drew attention to the fact that many Indo-European tribal names and some modern European surnames mean "wolf" or "wolf-men". This is argued by Eisler to indicate that the European transition from fruit gathering to predatory hunting was a conscious process, simultaneously accompanied by an emotional upheaval still remembered in humanity's subconscious, which in turn became reflected in the later medieval superstition of werewolves.[29]

Some modern researchers have tried to explain the reports of werewolf behaviour with recognised medical conditions. Dr Lee Illis of Guy's Hospital in London wrote a paper in 1963 entitled On Porphyria and the Aetiology of Werewolves, in which he argues that historical accounts on werewolves could have in fact been referring to victims of congenital porphyria, stating how the symptoms of photosensitivity, reddish teeth and psychosis could have been grounds for accusing a sufferer of being a werewolf[30]. This is however argued against by Woodward, who points out how mythological werewolves were almost invariably portrayed as resembling true wolves, and that their human forms were rarely physically conspicuous as porphyria victims.[7] Others have pointed out the possibility of historical werewolves having been sufferers of hypertrichosis, a hereditary condition manifesting itself in excessive hair growth. However, Woodward dismissed the possibility, as the rarity of the disease ruled it out from happening on a large scale, as werewolf cases were in medieval Europe.[7] People suffering from Downs Syndrome have been suggested by some scholars to have been possible originators of werewolf myths.[22] Woodward suggested rabies as the origin of werewolf beliefs, claiming remarkable similarities between the symptoms of that disease and some of the legends. Woodward focused on the idea that being bitten by a werewolf could result in the victim turning into one, which suggested the idea of a transmittable disease like rabies.[7] However, the idea that lycanthropy could be transmitted in this way is not part of the original myths and legends and only appears in relatively recent beliefs.

Vampiric connections

In Medieval Europe, the corpses of some people executed as werewolves were cremated rather than buried in order to prevent them from being resurrected as vampires.[7] Before the end of the 19th century, the Greeks believed that the corpses of werewolves, if not destroyed, would return to life as vampires in the form of wolves or hyenas which prowled battlefields, drinking the blood of dying soldiers. In the same vein, in some rural areas of Germany, Poland and Northern France, it was once believed that people who died in mortal sin came back to life as blood-drinking wolves. This differs from conventional werewolfery, where the creature is a living being rather than an undead apparition. These vampiric werewolves would return to their human corpse form at daylight. They were dealt with by decapitation with a spade and exorcism by the parish priest. The head would then be thrown into a stream, where the weight of its sins were thought to weigh it down. Sometimes, the same methods used to dispose of ordinary vampires would be used.[7] The vampire was also linked to the werewolf in East European countries, particularly Bulgaria, Serbia and Slovakia. In Serbia, the werewolf and vampire are known collectively as one creature; Vulkodlak.[7] In Hungarian and Balkan mythology, many werewolves were said to be vampiric witches who became wolves in order to suck the blood of men born under the full moon in order to preserve their health. In their human form, these werewolves were said to have pale, sunken faces, hollow eyes, swollen lips and flabby arms.[7] The Haitian jé-rouges differ from traditional European werewolves by their habit of actively trying to spread their lycanthropic condition to others, much like vampires.[7]

In fiction

The first feature film to use an anthropomorphic werewolf was Werewolf of London in 1935. The main werewolf of this film is a dapper London scientist who retains some of his style and most of his human features after his transformation,[31] as lead actor Henry Hull was unwilling to spend long hours being made up by makeup artist Jack Pierce.[32] Universal Studios drew on a Balkan tale of a plant associated with lycanthropy as there was no literary work to draw upon, unlike the case with vampires. There is no reference to silver nor other aspects of werewolf lore such as cannibalism.[33]

However, he lacks warmth, and it is left to the tragic character Talbot played by Lon Chaney, Jr. in 1941's The Wolf Man to capture the public imagination. With Pierce's makeup more elaborate this time,[34] this catapulted the werewolf into public consciousness.[31] Sympathetic portrayals are few but notable, such as the comedic but tortured protagonist David Naughton in An American Werewolf In London,[35] and a less anguished and more confident and charismatic Jack Nicholson in the 1994 film Wolf.[36] Rachel Hawthorne's Dark Guardian novels examine a secret society of werewolves who live peacefully alongside normal humans, are able to initiate the change at will to protect their kind, and generally retain control of themselves when transformed.[37] Other werewolves are decidedly more willful and malevolent, such as those in the novel The Howling and its subsequent sequels and film adaptations.

The form a werewolf assumes was generally anthropomorphic in early films such as The Wolf Man and Werewolf of London, but larger and powerful wolf in many later films.[38]

The transmogrification process is often portrayed as painful in film and literature within the horror genre. The resulting wolf is typically cunning but merciless and prone to killing and eating people without compunction, regardless of the moral character of its human counterpart.

Werewolves are often depicted as immune to damage caused by ordinary weapons, being vulnerable only to silver objects, such as a silver-tipped cane, bullet or blade; this attribute was first adopted cinematically in The Wolf Man.[34] This negative reaction to silver is sometimes so strong that the mere touch of the metal on a werewolf's skin will cause burns. Current-day werewolf fiction almost exclusively involves lycanthropy being either a hereditary condition or being transmitted like an infectious disease by the bite of another werewolf. In some fiction, the power of the werewolf extends to human form, such as invulnerability, super-human speed and strength and falling on their feet from high falls. Also aggressiveness and animalistic urges may be harder to control (hunger, sexual harassment). Usually in these cases the abilities are diminished in human form. In other fictions it can even be cured by medicine men or even antidotes.

Fantastic literature sometimes includes the painful element to the change, but often does not. For example, J. K. Rowling maintains the painful transition between forms while Charles de Lint, Terry Pratchett, Fritz Leiber, and myriad others reach back to the non-painful medieval literary sources. Poul Anderson in Operation Chaos presents a modernised American werewolf, in complete control of himself and free of the traditional taints, while in Three Hearts and Three Lions appears a far more traditional (though not unsympathetic) female werewolf.

The 1961 Hammer film The Curse of the Werewolf, adapted from the 1933 novel The Werewolf of Paris by American author Guy Endore, in 1961 draws on traditional legends of a child born on Christmas Eve being cursed.[39]

See also

- Skin-walker

- Beast of Bray Road

- Beast of Gévaudan

- Damarchus

- Werewolf witch trials

- Rougarou

- Vârcolac

- Werecat

- Werwolf

- Wolf of Magdeburg

- Wulver

Footnotes

- ↑ This may sound very peculiar but it is a fact firmly established in french folk-lore

- ↑ "Werwolf". gebruder Grimm. http://germazope.uni-trier.de/Projects/WBB/woerterbuecher/woerterbuecher/dwb/wbgui?lemmode=lemmasearch&mode=hierarchy&textsize=600&onlist=&word=werwolf&lemid=GW17531&query_start=1&totalhits=0&textword=&locpattern=&textpattern=&lemmapattern=&verspattern=#GW17531L0. Retrieved 2005-07-06.

- ↑ Rose, C. (2000). Giants, Monsters & Dragons: An Encyclopedia of Folklore, Legend and Myth. New York: Norton. p. 230. ISBN 0-393-32211-4.

- ↑ "Versipellis". Perseus Digital Library. http://perseus.uchicago.edu/hopper/text.jsp?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0062%3Aentry%3Dversipellis. Retrieved 2006-09-23.

- ↑ "loup-garou". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4 ed.). 2000. http://www.bartleby.com/61/7/L0260700.html.

- ↑ "Appendix I: Indo-European Roots: w-ro-". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4 ed.). 2000. http://www.bartleby.com/61/roots/IE588.html.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 7.16 7.17 7.18 7.19 7.20 7.21 7.22 7.23 7.24 7.25 Woodward, Ian (1979). The Werewolf Delusion. New York: Paddington Press. p. 256. ISBN 0448231700. OCLC 4493753.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Bennett, Aaron. “So, You Want to be a Werewolf?” Fate. Vol. 55, no. 6, Issue 627. July 2002.

- ↑ O'Donnell, Elliot. Werwolves. Methuen. London. 1912. pp.65-67

- ↑ Ger shenson, Daniel. Apollo the Wolf-God. (Journal of Indo- European Studies, Monograph, 8.) McLean, Virginia: Institute for the Study of Man, 1991, ISBN 0941694380 pp.136-7

- ↑ Robert Jackson (1995) Witchcraft and the Occult. Devizes, Quintet Publishing: 25

- ↑ Herodotus. "105". Histories.

- ↑ Virgil. "viii". Eclogues. p. 98.

- ↑ Ovid. "i". Metamorphoses.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder. "viii". Historia Naturalis. p. 81. http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/L/Roman/Texts/Pliny_the_Elder/8*.html#81. 22/34

- ↑ Petronius (1996). Satyrica. R. Bracht Branham and Daniel Kinney. Berkeley: University of California. p. 56. ISBN 0-520-20599-5.

- ↑ Baring-Gould, p. 100

- ↑ Szabó, György. Mitológiai kislexikon, I-II., Budapest: Merényi Könyvkiadó (év nélkül) Mitólogiai kislexikon

- ↑ Willis, Roy; Davidson, Hilda Ellis (1997). World Mythology: The Illustrated Guide. Piaktus. ISBN 0-7499-1739-3. OCLC 37594992.

- ↑ The Fables of Mkhitar Gosh (New York, 1987), translated with an introduction by R. Bedrosian, edited by Elise Antreassian and illustrated by Anahid Janjigian

- ↑ "iii". Demonologie.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Lopez, Barry (1978). Of Wolves and Men. New York: Scribner Classics. ISBN 0743249364. OCLC 54857556.

- ↑ Legends of Grosse Pointe

- ↑ "Is the fear of wolves justified? A Fennoscandian perspective." (PDF). Acta Zoologica Lituanica, 2003, Volumen 13, Numerus 1. http://www.lcie.org/Docs/Regions/Baltic/Linnell%20AZL%20Wolf%20attacks%20in%20Fennoscandia.pdf. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

- ↑ Facundo Quiroga, "The Tiger of the Argentine Prairies" and the Legend of the "runa uturuncu". (Spanish)

- ↑ The Legend of the runa uturuncu in the Mythology of the Latin-American Guerilla. (Spanish)

- ↑ The Guaraní Myth about the Origin of Human Language and the Tiger-men. (Spanish)

- ↑ J.B. Ambrosetti (1976). Fantasmas de la selva misionera ("Ghosts of the Misiones Jungle"). Editorial Convergencia: Buenos Aires.

- ↑ Eisler, Robert (1948). Man Into Wolf - An Anthropological Interpretation of Sadism, Masochism, and Lycanthropy. ASIN B000V6D4PG.

- ↑ Illis, L. (Jan 1964). "On Porphyria and the Aetiology of Werewolves.". Proc R Soc Med 57: 23–6. PMID 14114172.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Searles B (1988). Films of Science Fiction and Fantasy. New York: Harry N. Abrams. pp. 165–67. ISBN 0-8109-0922-7.

- ↑ Clemens, p. 119-20

- ↑ Clemens, p. 117-18

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Clemens, p. 120

- ↑ Steiger 1999, p. 12

- ↑ Steiger 1999, p. 330

- ↑ Hawthorne, Rachel (August 25, 2009). "Dark of the Moon". harperteen.com. http://browseinside.harperteen.com/index.aspx?isbn13=9780061709579. Retrieved December 22, 2009.

- ↑ Steiger 1999, p. 17

- ↑ Clemens, p. 208

References

- Baring-Gould, Sabine (1973 [1865]) (Google books). The Book of Werewolves: Being an Account of a Terrible Superstition. New York, NY: Causeway Books. ISBN 0-88356-008-9. OCLC 1084970. http://books.google.com/?id=AfczULIXGscC&lpg=PP1&dq=sabine%20baring-gould%20the%20book%20of%20werewolves&pg=PP14#v=onepage&q=. Retrieved 2009-11-16.

- Clemens, Carlos (1968). Horror Movies: An illustrated Survey. London: Panther Books.

- Douglas, Adam (1992). The Beast Within: A History of the Werewolf. London: Chapmans. ISBN 0-380-72264-X.

- Lecouteux, Claude (2003). Witches, Werewolves, and Fairies. Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions International. ISBN 089281096-3.

- Prieur, Claude. Dialogue de la Lycanthropie: Ou transformation d'hommes en loups, vulgairement dits loups-garous, et si telle se peut faire. Louvain: J. Maes & P. Zangre, 1596. (By a Franciscan monk, in French)

- Steiger, Brad (1999). The Werewolf Book: The Encyclopedia of Shapeshifting Beings. Farmington Hills, MI: Visible Ink. ISBN 1-57859-078-7. OCLC 41565057.

- Summers, Montague, The Werewolf London: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner, 1933. (1st edition, reissued 1934 New York: E.P. Dutton, 1966 New Hyde Park, N.Y: University Books, 1973 Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press, 2003 Mineola, N.Y.: Dover, with new title The Werewolf in Lore and Legend). ISBN 0-7661-3210-2

- Wolfeshusius, Johannes Fridericus. De Lycanthropia: An vere illi, ut fama est, luporum & aliarum bestiarum formis induantur. Problema philosophicum pro sententia Joan. Bodini ... adversus dissentaneas aliquorum opiniones noviter assertum... Leipzig: Typis Abrahami Lambergi, 1591. (In Latin; microfilm held by the United States National Library of Medicine)

- Woodward, Ian (1979). The Werewolf Delusion. Paddington Press. ISBN 0448231700.

External links

- Arby Stones, "Hellhounds, Werewolves and the Germanic Underworld"

- The Book of Were-Wolves, by Sabine Baring-Gould, 1865 (Google online books)

- Therianthropy History Timeline

- Allen Varney, "The New Improved Beast"

- A Translation of Grimm's Saga No. 213 The Werewolf

- A Translation of Grimm's Saga No. 215 The Werewolf Stone