Lothal

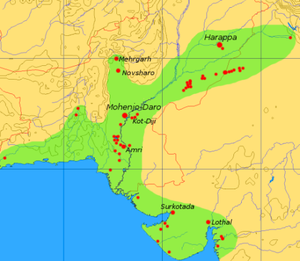

Lothal (Gujarati: લોથલ loˑt̪ʰəl) is one of the most prominent cities of the ancient Indus valley civilization. Located in Bhāl region of the modern state of Gujarāt and dating from 2400 BCE, it is one of India's most important archaeological sites that date from that era. Discovered in 1954, Lothal was excavated from February 13, 1955 to May 19, 1960 by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI).

Lothal's dock—the world's earliest known—connected the city to an ancient course of the Sabarmati river on the trade route between Harappan cities in Sindh and the peninsula of Saurashtra when the surrounding Kutch desert of today was a part of the Arabian Sea. It was a vital and thriving trade centre in ancient times, with its trade of beads, gems and valuable ornaments reaching the far corners of West Asia and Africa. Lothal's people were responsible for the earliest-known portrayals of realism in art and sculpture, telling some of the most well-known fables of today. Its scientists used a shell compass and divided the horizon and sky into 8–12 whole parts, possibly pioneering the study of stars and advanced navigation—2000 years before the Greeks. The techniques and tools they pioneered for bead-making and in metallurgy have stood the test of time for over 4000 years.

Lothal is situated near the village of Saragwala in the Dholka taluka of Ahmedabad district. It is at a distance of six kilometres (south-east) from the Lothal-Bhurkhi railway station on the Ahmedabad-Bhavnagar railway line. It is also connected by all-weather roads to the cities of Ahmedabad (85 km/53 mi), Bhavnagar, Rajkot and Dholka. Nearest cities are Dholka and Bagodara. Resuming excavation in 1961, archaeologists unearthed trenches sunk on the northern, eastern and western flanks of the mound, bringing to light the inlet channels and nullah ("ravine", or "gully") connecting the dock with the river. The findings consist of a mound, a township, a marketplace and the dock. Adjacent to the excavated areas stands the Archaeological Museum, where some of the most prominent collections of Indus-era antiquities in modern India are displayed.

Contents |

Archaeology

The meaning of Lothal (a combination of Loth and (s) thal) in Gujarati to be "the mound of the dead" is not unusual, as the name of the city of Mohenjodaro in Sindhi means the same. People in villages neighbouring to Lothal had known of the presence of an ancient town and human remains. As recently as 1850, boats sailed up to the mound, and timber was shipped in 1942 from Broach to Saragwala via the mound. A silted creek connecting modern Bholad with Lothal and Saragwala represents the ancient flow channel of a river or creek.[1] When India was partitioned in 1947, most of the sites, including Mohenjodaro and Harappa, came to be located in the state of Pakistan. The Archaeological Survey of India undertook a new program of exploration, and excavated many sites across Gujarat. Between 1954 and 1958, more than 50 sites were excavated in the Kutch {see also Dholavira}, and Saurashtra peninsulas, extending the limits of Harappan civilization by 500 kilometres (310 mi) to the river Kim, where the Bhagatrav site accesses the valley of the rivers Narmada and Tapti. Lothal stands 270 kilometres (170 mi) from Mohenjodaro, which is in Sindh.[2] It has also been speculated that owing to the comparatively small dimensions of the main city, Lothal was not a large settlement at all, and its "dock" was perhaps an irrigation tank.[3] However, the ASI and other contemporary archaeologists assert that the city was a part of a major river system on the trade route of the ancient peoples from Sindh to Saurashtra in Gujarat. Cemeteries have been found which indicate that its people were probably of Dravidian, Proto-Australoid or Mediterranean physiques. Lothal provides with the largest collection of antiquities in the archaeology of modern India.[4] It is essentially a single culture site—the Harappan culture in all its variances is evidenced. An indigenous micaceous Red Ware culture also existed, which is believed to be autochthonous and pre-Harappan. Two sub-periods of Harappan culture are distinguished: the same period (between 2400 and 1900 BCE) is identical to the exuberant culture of Harappa and Mohenjodaro.

After the core of the Indus civilization had decayed in Mohenjodaro and Harappa, Lothal seems not only to have survived but to have thrived for many years. But its constant threats, tropical storms and floods, caused immense destruction, which destabilized the culture and ultimately caused its end. Topographical analysis also shows signs that at about the time of its demise, the region suffered from aridity or weakened monsoon rainfall. Thus the cause for the abandonment of the city may have been changes in the climate as well as natural disasters, as suggested by environmental magnetic records.[5] Lothal is based upon a mound that was a salt marsh inundated by tide. Remote sensing and topographical studies published by Indian scientists in the Journal of the Indian Geophysicists Union in 2004 revealed an ancient, meandering river adjacent to Lothal, 30 kilometres (19 mi) in length according to satellite imagery—an ancient extension of the northern river channel bed of a tributary of the Bhogavo river. Small channel widths (10–300 m/30–1000 ft) when compared to the lower reaches (1.2–1.6 km/0.75–1.0 mi) suggest the presence of a strong tidal influence upon the city—tidal waters ingressed up to and beyond the city. Upstream elements of this river provided a suitable source of freshwater for the inhabitants.[5]

History

Before the arrival of Harappan people (c. 2400 BCE), Lothal was a small village next to the river providing access to the mainland from the Gulf of Khambhat. The indigenous peoples maintained a prosperous economy, attested by the discovery of copper objects, beads and semi-precious stones. Ceramic wares were of fine clay and smooth, micaceous red surface. A new technique of firing pottery under partly-oxidising and reducing conditions was improved by them—designated black-and-red ware, to the micaceous Red Ware. Harappans were attracted to Lothal for its sheltered harbour, rich cotton and rice-growing environment and bead-making industry. The beads and gems of Lothal were in great demand in the west. The settlers lived peacefully with the Red Ware people, who adopted their lifestyle—evidenced from the flourishing trade and changing working techniques—Harappans began producing the indigenous ceramic goods, adopting the manner from the natives.[6]

Town planning

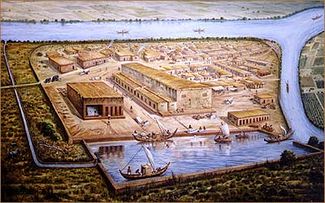

A flood destroyed village foundations and settlements (c. 2350 BCE). Harappans based around Lothal and from Sindh took this opportunity to expand their settlement and create a planned township on the lines of greater cities in the Indus valley.[7] Lothal planners engaged themselves to protect the area from consistent floods. The town was divided into blocks of 1–2-metre-high (3–6 ft) platforms of sun-dried bricks, each serving 20–30 houses of thick mud and brick walls. The city was divided into a citadel, or acropolis and a lower town. The rulers of the town lived in the acropolis, which featured paved baths, underground and surface drains (built of kiln-fired bricks) and a potable water well. The lower town was subdivided into two sectors — the north-south arterial street was the main commercial area — flanked by shops of rich and ordinary merchants and craftsmen. The residential area was located to either side of the marketplace. The lower town was also periodically enlarged during Lothal's years of prosperity.

Lothal engineers accorded high priority to the creation of a dockyard and a warehouse to serve the purposes of naval trade. While the consensus view amongst archaeologists identifies this structure as a "dockyard," it has also been suggested that owing to small dimensions, this basin may have been an irrigation tank and canal.[3] The dock was built on the eastern flank of the town, and is regarded by archaeologists as an engineering feat of the highest order. It was located away from the main current of the river to avoid silting, but provided access to ships in high tide as well. The warehouse was built close to the acropolis on a 3.5-metre-high (10.5 ft) podium of mud bricks. The rulers could thus supervise the activity on the dock and warehouse simultaneously. Facilitating the movement of cargo was a mud-brick wharf, 220 metres (720 ft) long, built on the western arm of the dock, with a ramp leading to the warehouse.[8] There was an important public building opposite to the warehouse whose superstructure has completely disappeared. Throughout their time, the city had to brace itself through multiple floods and storms. Dock and city peripheral walls were maintained efficiently. The town's zealous rebuilding ensured the growth and prosperity of the trade. However, with rising prosperity, Lothal's people failed to upkeep their walls and dock facilities, possibly as a result of over-confidence in their systems. A flood of moderate intensity in 2050 BCE exposed some serious weaknesses in the structure, but the problems were not addressed properly.[9]

Economy and urban culture

The uniform organization of the town and its institutions give evidence that the Harappans were a very disciplined people.[10] Commerce and administrative duties were performed according to standards laid out. Municipal administration was strict — the width of most streets remained the same over a long time, and no encroached structures were built. Householders possessed a sump, or collection chamber to deposit solid waste in order to prevent the clogging of city drains. Drains, manholes and cesspools kept the city clean and deposited the waste in the river, which was washed out during high tide. A new provincial style of Harappan art and painting was pioneered — new approaches included realistic portrayals of animals in their natural surroundings, including the portrayal of stories and folklore. Fire-altars were built in public places. Metalware, gold and jewellery and tastefully decorated ornaments attest to the culture and prosperity of the people of Lothal.

Most of their equipment—metal tools, weights, measures, seals, earthenware and ornaments—were of the uniform standard and quality found across the Indus civilization. Lothal was a major trade centre, importing en masse raw materials like copper, chert and semi-precious stones from Mohenjo-daro and Harappa, and mass distributing to inner villages and towns. It also produced large quantities of bronze celts, fish-hooks, chisels, spears and ornaments. Lothal exported its beads, gemstones, ivory and shells. The stone blade industry catered to domestic needs—fine chert was imported from the Sukkur valley or from Bijapur in modern Karnataka. Bhagatrav supplied semi-precious stones while chank shell came from Dholavira and Bet Dwarka. An intensive trade network gave the inhabitants great prosperity—it stretched across the frontiers to Egypt, Bahrain and Sumer.[9] One of the evidence of trade in Lothal is the discovery of typical Persian gulf seals, a circular button sealThe rise of civilization in India and Pakistan by Bridget and F. Raymond Allchin. p. 187

Declining years

While the wider debate over the end of Indus civilization continues, archaeological evidence gathered by the ASI appears to point to natural catastrophes, specifically floods and storms as the source of Lothal's downfall. A powerful flood submerged the town and destroyed most of the houses, with the walls and platforms heavily damaged. The acropolis and the residence of the ruler were levelled (2000-1900 BCE), and inhabited by common tradesmen and newly built makeshift houses. The worst consequence was the shift in the course of the river, cutting off access to the ships and dock.[11] Despite the ruler leaving the city, the leaderless people built a new but shallow inlet to connect the flow channel to the dock for sluicing small ships into the basin. Large ships were moored away. Houses were rebuilt, yet without removal of flood debris, which made them poor-quality and susceptible to further damage. Public drains were replaced by soakage jars. The citizens did not undertake encroachments, and rebuilt public baths and maintained fire worship. However, with a poorly organised government, and no outside agency or central government, the public works could not be properly repaired or maintained. The heavily damaged warehouse was never repaired properly, and stocks were stored in wooden canopies, exposed to floods and fire. The economy of the city was transformed. Trade volumes reduced greatly, though not catastrophically, and resources were available in lesser quantities. Independent businesses caved, allowing a merchant-centric system of factories to develop where hundreds of craftsmen worked for the same supplier and financier. The bead factory had ten living rooms and a large workplace courtyard. The coppersmith's workshop had five furnaces and paved sinks to enable multiple artisans to work.[12]

The declining prosperity of the town, paucity of resources and poor administration increased the woes of a people pressured by consistent floods and storms. Increased salinity of soil made the land inhospitable to life, including crops. This is evidenced in adjacent cities of Rangpur, Rojdi, Rupar and Harappa in Punjab, Mohenjo-daro and Chanhudaro in Sindh. A massive flood (c. 1900 BCE) completely destroyed the flagging township in a single stroke. Archaeological analysis shows that the basin and dock were sealed with silt and debris, and the buildings razed to the ground. The flood affected the entire region of Saurashtra, Sindh and south Gujarat, and affected the upper reaches of the Indus and Sutlej, where scores of villages and townships were washed away. The population fled to inner regions.[13]

Later Harappan culture

Archaeological evidence shows that the site continued to be inhabited, albeit by a much smaller population devoid of urban influences. The few people who returned to Lothal could not reconstruct and repair their city, but surprisingly continued to stay and preserved religious traditions, living in poorly-built houses and reed huts. That they were the Harappan peoples is evidenced by the analyses of their remains in the cemetery. While the trade and resources of the city were almost entirely gone, the people retained several Harappan ways in writing, pottery and utensils. About this time ASI archaeologists record a mass movement of refugees from Punjab and Sindh into Saurashtra and to the valley of Sarasvati (1900-1700 BCE).[14] Hundreds of ill-equipped settlements have been attributed to this people as Late Harappans—a completely de-urbanised culture characterised by rising illiteracy, undiversified economy, unsophisticated administration and poverty. Though Indus seals went out of use, the system of weights with an 8.573 gram (0.3024 oz avoirdupois) unit was retained. Between 1700 and 1600 BCE, trade would revive again. In Lothal, Harappan ceramic works of bowls, dishes and jars were mass-produced. Merchants used local materials such as chalcedony instead of chert for stone blades. Truncated sandstone weights replaced hexahedron chert weights. The sophisticated writing was simplified by exempeting pictorial symbols, and the painting style reduced itself to wavy lines, loops and fronds.

Civilization

The people of Lothal made significant and often unique contributions to human civilization in the Indus era, in the fields of city planning, art, architecture, science, engineering and religion. Their work in metallurgy, seals, beads and jewellery was the basis of their prosperity.

Science and engineering

A thick ring-like shell object found with four slits each in two margins served as a compass to measure angles on plane surfaces or in the horizon in multiples of 40 degrees, up to 360 degrees. Such shell instruments were probably invented to measure 8–12 whole sections of the horizon and sky, explaining the slits on the lower and upper margins. Archaeologists consider this as evidence that the Lothal experts had achieved something 2,000 years before the Greeks: an 8–12 fold division of horizon and sky, as well as an instrument for measuring angles and perhaps the position of stars, and for navigation.[15] Lothal contributes one of three measurement scales that are integrated and linear (others found in Harappa and Mohenjodaro). An ivory scale from Lothal has the smallest-known decimal divisions in Indus civilization. The scale is 6 millimetres (0.2 inches) thick, 15 mm (0.6 inches) broad and the available length is 128 mm (5.0 inches), but only 27 graduations are visible over 46 mm (1.8 inches), the distance between graduation lines being 1.70 mm (0.067 inches) (the small size indicates use for fine purposes). The sum total of ten graduations from Lothal is approximate to the angula in the Arthashastra.[16] The Lothal craftsmen took care to ensure durability and accuracy of stone weights by blunting edges before polishing.[17]

For their renowned draining system, Lothal engineers provided corbelled roofs, and an apron of kiln-fired bricks over the brick face of the platform where the sewerage entered the cesspool. Wooden screens inserted in grooves in the side drain walls held back solid waste. The well is built of radial bricks, 2.4 metres (7.9 ft) in diameter and 6.7 metres (22 ft) deep. It had an immaculate network of underground drains, silting chambers and cesspools, and inspection chambers for solid waste. The extent of drains provided archaeologists with many clues regarding the layout of streets, organization of housing and baths. On average, the main sewer is 20–46 cm (7.8–18.1 inches) in depth, with outer dimensions of 86 × 68 × 33 cm (34 × 27 × 13 in). Lothal brick-makers used a logical approach in manufacture of bricks, designed with care in regards to thickness of structures. They were used as headers and stretchers in same and alternate layers. Archaeologists estimate that in most cases, the bricks were in ratio 1:0.5:0.25 on three sides, in dimensions which were integral multiples of large graduations of Lothal scale of 25 mm (1.0 in).[18]

Religion and disposal of the dead

.png)

The people of Lothal worshipped a fire god, speculated to be the horned deity depicted on seals named Atha (Athar) and Arka, which is also evidenced by the presence of private and public fire-altars where sacrifices of animals and cattle were apparently conducted. Archaeologists have discovered gold pendants, charred ashes of terra-cotta cakes and pottery, bovine remains, beads and other signs that may indicate the practice of the Gavamayana sacrifice, associated with the ancient Vedic religion.[19] Animal worship is also evidenced, but not the worship of the Mother Goddess that is evidenced in other Harappan cities—experts consider this a sign of the existence of diversity in religious traditions. However, it is believed that a sea goddess, perhaps cognate with the general Indus-era Mother Goddess, was worshipped. Today, the local villagers likewise worship a sea goddess, Vanuvati Sikotarimata, suggesting a connection with the ancient port's traditions and historical past as an access to the sea.[20][21] But the archaeologists also discovered that the practice had been given up by 2000 BCE (determined by the difference in burial times of the carbon-dated remains). It is suggested that the practice occurred only on occasion. It is also considered that given the small number of graves discovered—only 17 in an estimated population of 15,000—the citizens of Lothal also practiced cremation of the dead. Post-cremation burials have been noted in other Indus sites like Harappa, Mehi and Damb-Bhuti.[22] The mummified remains of an Assyrian and an Egyptian corpse were also discovered at the mound.

Metallurgy and jewellery

Lothali copper is unusually pure, lacking the arsenic typically used by coppersmiths across the rest of the Indus valley. The city imported ingots from probable sources in the Arabian peninsula. Workers mixed tin with copper for the manufacture of celts, arrowheads, fishhooks, chisels, bangles, rings, drills and spearheads, although weapon manufacturing was minor. They also employed advanced metallurgy in following the cire perdue technique of casting, and used more than one-piece moulds for casting birds and animals.[23] They also invented new tools such as curved saws and twisted drills unknown to other civilizations at the time.[24]

Lothal was one of the most important centres of production for shell-working, owing to the abundance of chank shell of high quality found in the Gulf of Kutch and near the Kathiawar coast[23] Gamesmen, beads, unguent vessels, chank shells, ladles and inlays were made for export and local consumption. Components of stringed musical instruments like the plectrum and the bridge were made of shell.[25] An ivory workshop was operated under strict official supervision, and the domestication of elephants has been suggested. An ivory seal, and sawn pieces for boxes, combs, rods, inlays and ear-studs were found during excavations.[25] Lothal produced a large quantity of gold ornaments—the most attractive item being microbeads of gold in five strands in necklaces, unique for being less than 0.25 millimetres (0.010 inches) in diameter. Cylindrical, globular and jasper beads of gold with edges at right angles resemble modern pendants used by women in Gujarat in plaits of hair. A large disc with holes recovered from a sacrificial altar is compared to the rukma worn by Vedic priests. Studs, cogwheel and heart-shaped ornaments of fainence and steatite were popular in Lothal. A ring of thin copper wire turned into double spirals resembles the gold-wire rings used by modern Hindus for weddings.[26]

Art

The discovery of etched carnelian beads and non-etched barrel beads in Kish and Ur (modern Iraq), Jalalabad (Afghanistan) and Susa (Iran) attest to the popularity of the Lothal-centric bead industry across West Asia.[27] The lapidaries show a refined taste in selecting stones of variegated colours, producing beads of different shapes and sizes. The methods of Lothal bead-makers were so advanced that no improvements have been noted over 4,000 years—modern makers in the Khambhat area follow the same technique. Double-eye beads of agate and collared or gold-capped beads of jasper and carnelian beads are among those attributed as uniquely from Lothal. It was very famous for micro-cylindrical beads of steatite (chlorite).[26]

.png)

Lothal has yielded 213 seals, third in importance amongst all Indus sites, considered masterpieces of glyptic art and calligraphy. Seal-cutters preferred short-horned bulls, mountain goats, tigers and composite animals like the elephant-bull for engravings. There is a short inscription of intaglio in almost every seal. Stamp seals with copper rings inserted in a perforated button were used to sealing cargo, with impressions of packing materials like mats, twisted cloth and cords—a fact verified only at Lothal. Quantitative descriptions, seals of rulers and owners were stamped on goods. A unique seal found here is from Bahrain—circular, with motif of a dragon flanked by jumping gazelles.[28]

Lothal offers two new types of potter work—a convex bowl with or without stud handle, and a small jar with flaring rim, both in the micaceous Red Ware period—not found in contemporary Indus cultures. Lothal artists introduced a new form of painting closely linked to modern realism.[29] Paintings depict animals in their natural surroundings. Indeed, upon one large vessel, the artist depicts birds—with fish in their beaks—resting in a tree, while a fox-like animal stands below. This scene bears resemblance to the story of the crow and cunning fox in Panchatantra.[30] Artistic imagination is also suggested via careful portrayals—for example, several birds with legs aloft in the sky suggest flight, while half-opened wings suggest imminent flight. On a miniature jar, the story of the thirsty crow and deer is depicted—of how the deer could not drink from the narrow-mouth of the jar, while the crow succeeded by dropping stones in the jar. The features of the animals are clear and graceful. Movements and emotions are suggested by the positioning of limbs and facial features—in a 15 × 5 cm (6 × 2 in) jar without overcrowding.[30]

A complete set of terra-cotta gamesmen, comparable to modern chessmen, has been found in Lothal—animal figures, pyramids with ivory handles and castle-like objects (similar to the chess set of Queen Hatshepsut in Egypt).[31] The realistic portrayal of human beings and animals suggests a careful study of anatomical and natural features. The bust of a male with slit eyes, sharp nose and square-cut beard is reminiscent of Sumerian figures, especially stone sculptures from Mari. In images of men and women, muscular and physical features are sharp, prominently marked. Terra-cotta models also identify the differences between species of dogs and bulls, including those of horses. Animal figures with wheels and a movable head were used as toys.

Excavated Lothal

On plan, Lothal stands 285 metres (935 ft) north-to-south and 228 metres (748 ft) east-to-west. At the height of its habitation, it covered a wider area since remains have been found 300 metres (1000 ft) south of the mound. Due to the fragile nature of unbaked bricks and frequent floods, the superstructures of all buildings have receded. Dwarfed walls, platforms, wells, drains, baths and paved floors are visible.[9] But thanks to the loam deposited by persistent floods, the dock walls were preserved beyond the great deluge (c. 1900 BCE). The absence of standing high walls is attributed to erosion and brick robbery. The ancient nullah, the inlet channel and riverbed have been similarly covered up. The flood-damaged peripheral wall of mud-bricks is visible near the warehouse area. The remnants of the north-south sewer are burnt bricks in the cesspool. Cubical blocks of the warehouse on a high platform are also visible.[9]

The ASI has covered the peripheral walls, the wharf and many houses of the early phase with earth to protect from natural phenomena, but the entire archaeological site is nevertheless facing grave concerns about necessary preservation. Salinity ingress and prolonged exposure to the rain and sun are gradually eating away the remains of the site. But there are no barricades to prevent the stream of visitors from trudging on the delicate brick and mud work. Stray dogs throng the mound unhindered. Heavy rain in the region has damaged the remains of the sun-dried mud brick constructions. Stagnant rain water has lathered the brick and mud work with layers of moss. Due to siltation, the dockyard’s draft has been reduced by 3–4 metres (10–13 ft) and saline deposits are decaying the bricks. Officials blame the salinity on capillary action and point out that cracks are emerging and foundations weakening even as restoration work slowly progresses.[32]

Dock and warehouse

The dock was located away from the main current to avoid deposition of silt. Modern oceanographers have observed that the Harappans must have possessed great knowledge relating to tides in order to build such a dock on the ever-shifting course of the Sabarmati, as well as exemplary hydrography and maritime engineering. This was the earliest known dock found in the world, equipped to berth and service ships.[33] It is speculated that Lothal engineers studied tidal movements, and their effects on brick-built structures, since the walls are of kiln-burnt bricks. This knowledge also enabled them to select Lothal's location in the first place, as the Gulf of Khambhat has the highest tidal amplitude and ships can be sluiced through flow tides in the river estuary. The engineers built a trapezoidal structure, with north-south arms of average 21.8 metres (71.5 ft), and east-west arms of 37 metres (121 ft).[34] Another assessment is that the basin could have served as an irrigation tank, for the estimated original dimensions of the "dock" are not large enough, by modern standards, to house ships and conduct much traffic.[3]

The original height of the embankments was 4.26 metres (13.98 ft). (Now it is 3.35 metres (10.99 ft).) The main inlet is 12.8 metres (42.0 ft) wide, and another is provided on the opposite side. To counter the thrust of water, offsets were provided on the outer wall faces. When the river changed its course in 2000 BCE, a smaller inlet, 7 metres (23 ft) wide was made in the longer arm, connected to the river by a 2 kilometre (3.2 mi) channel. At high tide a flow of 2.1–2.4 metres (6.9–7.9 ft) of water would have allowed ships to enter. Provision was made for the escape of excess water through the outlet channel, 96.5 metres (317 ft) wide and 1.7 metres (5.6 ft) high in the southern arm. The dock also possessed a lock-gate system—a wooden door could be lowered at the mouth of the outlet to retain a minimum column of water in the basin so as to ensure floatation at low tides.[34] Central to the city's economy, the warehouse was originally built on sixty-four cubical blocks, 3.6 metres (11.8 ft) square, with 1.2-metre (3.9-ft) passages, and based on a 3.5-metre-high (11.5 ft) mud-brick podium. The pedestal was very high to provide maximum protection from floods. Brick-paved passages between blocks served as vents, and a direct ramp led to the dock to facilitate loading. The warehouse was located close to the acropolis, to allow tight supervision by ruling authorities. Despite elaborate precautions, the major floods that brought the city's decline destroyed all but twelve blocks, which became the make-shift storehouse.[35]

Acropolis and Lower town

Lothal's acropolis was the town centre, its political and commercial heart, measuring 127.4 metres (418 ft) east-to-west by 60.9 metres (200 ft) north-to-south. Apart from the warehouse, it was the residence of the ruling class. There were three streets and two lanes running east-west, and two streets running north-south. The four sides of the rectangular platform on which houses were built are formed by mud-brick structures of 12.2–24.4 metre (40–80 ft) thickness and 2.1–3.6 metres (6.9–11.8 ft) high.[36] The baths were primarily located in the acropolis—mostly two-roomed houses with open courtyards. The bricks used for paving baths were polished to prevent seepage. The pavements were lime-plastered and edges were wainscoted (wooden panels) by thin walls. The ruler's residence is 43.92 square metres (472.8 sq ft) in area with a 1.8-square-meter-bath (19 sq ft) equipped with an outlet and inlet. The remains of this house give evidence to a sophisticated drainage system. The Lower town marketplace was on the main north-south street 6–8 metres (20–26 ft) wide. Built in straight rows on either side of the street are residences and workshops, although brick-built drains and early period housing has disappeared. The street maintained a uniform width and did not undergo encroachment during the reconstructive periods after deluges. There are multiple two-roomed shops and workplaces of coppersmiths and blacksmiths.[37]

The bead factory, which performs a very important economic function, possesses a central courtyard and eleven rooms, a store and a guardhouse. There is a cinder dump, as well as a double-chambered circular kiln, with stoke-holes for fuel supply. Four flues are connected with each other, the upper chamber and the stoke hold. The mud plaster of the floors and walls are vitrified owing to intense heat during work. The remnants of raw materials such as reed, cow dung, sawdust and agate are found, giving archaeologists hints of how the kiln was operated.[38] A large mud-brick building faces the factory, and its significance is noted by its plan. Four large rooms and a hall, with an overall measurement of 17.1 × 12.8 metres (56 × 42 ft). The hall has a large doorway, and a fire-altar is posed on a raised floor in the southern corner of the building. A square terra-cotta stump in the centre is associated with the place of worship found in the sister site of Kalibangan (in Rajasthan), making this a primary centre of worship for Lothal's people.[39]

Notes

- ↑ S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 2–3.

- ↑ Robert W. Bradnock, Anil Mulchandani (PHP). Rajasthan and Gujarat Handbook: The Travel Guide. Footprint Travel Guides. pp. 276. ISBN 1-900949-92-X. http://books.google.com/books?ie=UTF-8&vid=ISBN190094992X&id=vDmgMC-l17IC&dq=Lothal&lpg=PA277&pg=PA276&sig=cUu9MCM0DudYf0Md4EIRuJrKxJI. Retrieved 2006-10-26.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Lawrence S. Leshnik (October 1968). "The Harappan Port at Lothal: Another View". American Anthropologist (New Series, Vol. 70, No. 5). pp. 911–22. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0002-7294(196810)2%3A70%3A5%3C911%3ATH%22ALA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-2.

- ↑ S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 30–31.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Khadkikar et al. (2004). "Paleoenvironments around Lothal" (PDF). Journal of the Indian Geophysics Union (Vol. 8, No. 1). http://www.igu.in/8-1/5khadkikar.pdf.

- ↑ S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 5.

- ↑ S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 6.

- ↑ S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 7–8.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 11.

- ↑ S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 8.

- ↑ S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 12.

- ↑ S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 13.

- ↑ S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 13–14.

- ↑ S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 13–15.

- ↑ S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 40–41.

- ↑ S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 39–40.

- ↑ S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 39.

- ↑ S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 41.

- ↑ S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 43–45.

- ↑ S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 2.

- ↑ "India". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service. 2006. http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-46833/India. Retrieved 2006-04-06.

- ↑ S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 45.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 42.

- ↑ S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 41–42.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 43.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 33–34.

- ↑ S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 31–33.

- ↑ S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 35–36.

- ↑ S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 45–47.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 46.

- ↑ S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 47–48.

- ↑ Janyala Sreenivas. "Harappan mound needs the kiss of life". The Indian Express. http://www.indianexpress.com/india-news/ie20010820/top7.html. Retrieved 2006-10-27.

- ↑ S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 27–28.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 28–29.

- ↑ S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 17–18.

- ↑ S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 19–21.

- ↑ S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 23–24.

- ↑ S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 23.

- ↑ S. R. Rao (1985). Lothal. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 22.

References

- S. R. Rao, Lothal (published by the Director General, Archaeological Survey of India, 1985)

- A.S. Khadikar, N. Basaviah, T. K. Gundurao and C. Rajshekhar Paleoenvironments around the Harappan port of Lothal, Gujarat, western India, in Journal of the Indian Geophysicists Union (2004)

- Lawrence S. Leshnik, The Harappan "Port" at Lothal: Another View American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 70, No. 5 (Oct., 1968), pp. 911–922

- Robert Bradnock, Rajasthan and Gujarat Handbook: The Travel Guide ISBN 1-900949-92-X

- S. R. Rao, Lothal and the Indus Civilisation ISBN 0210222786

- S. R. Rao, Lothal: A Harappan Port Town (1955–1962) (Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India) ASIN: B0006E4EAC

- Sir John Marshall, Mohenjo-daro and Indus Civilisation I–III (1932)

- Dennys Frenez & Maurizio Tosi The Lothal Sealings: Records from an Indus Civilization Town at the Eastern End of the Maritime Trade Circuits across the Arabian Sea, in M. Perna (Ed.), Studi in Onore di Enrica Fiandra. Contributi di archeologia egea e vicinorientale, Naples 2005, pp. 65–103.

- S. P. Gupta (ed.), The Lost Sarasvati and the Indus Civilization (1995), Kusumanjali Prakashan, Jodhpur

- Jonathan Mark Kenoyer, Ancient cities of the Indus Valley Civilization (1998) Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-577940-1

External links

- Pictures of Lothal Remains

- Lothal

- A Walk through Lothal

- Lothal and Mohenjodaro

- An invitation to the Indus Civilization (Tokyo Metropolitan Museum)

- Ancient Civilizations Timeline

- The Harappan Civilization

- Indus artefacts

- Cache of Seal Impressions Discovered in Western India

- "Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization". Archived from the original on 2007-01-01. http://web.archive.org/web/20070101164930/http://www.ucl.ac.uk/~ucgadkw/members/indus.html.

- Collection of images