Loricariidae

| Loricariidae Fossil range: Upper Miocene - Recent[1] |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Pterygoplichthys sp. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Siluriformes |

| Superfamily: | Loricarioidea |

| Family: | Loricariidae Rafinesque, 1815 |

| Subfamilies | |

|

Delturinae |

|

Loricariidae is the largest family of catfish (Order Siluriformes), with almost 700 species and new species being described each year. Loricariids originate from fresh water habitats of Costa Rica, Panama, and tropical and subtropical South America. These fish are noted for the bony plates covering their bodies and their suckermouths. Several genera are sold as "plecos", notably the suckermouth catfish, Hypostomus plecostomus, and are popular as aquarium fish.

Contents |

Common names

Members of the family Loricariidae are commonly referred to as suckermouth armoured catfishes, armoured catfish, 'plecos' or simply 'plecs'; a shortened form of the species name plecostomus.[2]

These names are used practically interchangeably when referring to the Loricariidae. The name "Plecostomus" and its shortened forms have become synonymous with the Loricariidae in general, since Plecostomus plecostomus (now called Hypostomus plecostomus) was one of the first species imported into the fishkeeping hobby. This can cause some confusion as some unrelated fish may also be called plecostomus, such as the "Borneo Plecostomus", which are actually balitorid fishes.[3]

In their native range, these fish are known as cascudos or acarís.[4]

L-numbers

Some types of loricariids are often referred to by their 'L-number'; this has been become common since imports of loricariid catfish from South America often included specimens that had not been taxonomically described. Currently L-numbers are used not only by fishkeeping enthusiasts but by biologists since they represent a useful stopgap until a new species of fish is given a full taxonomic name.[5] It should be noted that in some cases two different L-numbered catfish have turned out to be different populations of the same species, while in other cases multiple (but superficially similar) species have all been traded under a single L-number.

Taxonomy and evolution

Because of their highly specialized morphology, loricariids have been recognized as a monophyletic assemblage in even the earliest classifications of the Siluriformes, meaning that it consists of a natural grouping with a common ancestor and all of its descendents.[6] Loricariidae is one of seven families in the superfamily Loricarioidea, along with Amphiliidae, Trichomycteridae, Nematogenyidae, Callichthyidae, Scoloplacidae, and Astroblepidae. Some of these families also exhibit suckermouths or armor, although never together as in Loricariids.[2]

This is the largest catfish family, including about 684 species in around 92 genera, with new species being described each year.[2] However, this family is in flux and revisions are likely.[2] For example, the subfamily Ancistrinae is accepted in as late as the 2006 edition of Nelson's Fishes of the World; it later becomes grouped as a tribe because of its recognition as a sister group to the Pterygoplichthyini.[2][4][7] Under Ambruster, six subfamilies are recognized: Delturinae, Hypoptopomatinae, Hypostominae, Lithogeneinae, Loricariinae, and Neoplecostominae.[7][8]

Monophyly for the family is strongly supported, except, possibly, the inclusion of Lithogenes.[9] Lithogenes is the only genus within the subfamily Lithogeneinae. This genus and subfamily, the most basal group in Loricariidae, is the sister group to the rest of the family.[10] Neoplecostominae is the most basal group among the loricariids with the exception of Lithogeneinae.[11] However, the genera of Neoplecostominae do not appear to form a monophyletic assemblage.[12] The two subfamilies Loricariinae and Hypoptopomatinae appear to be generally regarded as monophyletic. However, the monophyly and composition of the other subfamilies are currently being examined and will likely be altered substantially in the future.[9] Hypostominae is the largest subfamily of Loricariidae. It is made up of five tribes. Four of the five tribes, Corymbophanini, Hypostomini, Pterygoplichthyini, and Rhinelepini, include about 24 genera. The fifth and largest tribe, Ancistrini (formerly recognized as its own subfamily), includes 30 genera.[13]

Loricariid fossils are extremely rare.[14] The fossil record of Loricariidae extends back to the upper Miocene.[1] Within the superfamily Loricarioidea, Loricariidae is the most derived; in this superfamily, there is a trend toward increasingly complex jaw morphology, which may have allowed for the great diversification of the Loricariidae, which have the most advanced jaws.[15]

Distribution and habitat

The family Loricariidae is vastly distributed over both sides of the Andes; on the other hand, most species are generally restricted to small geographic ranges.[16] Loricariids are found in fresh water habitats of Costa Rica, Panama, and South America. Species occur in swift-flowing streams from the lowlands up to 3,000 metres in elevation.[2] They can also be found in a variety of other freshwater environments.[3] They can be found in torrential mountain rivers, quiet brackish estuaries, black acidic waters, and even in subterranean habitats.[6]

Description and biology

This family has extremely variable color patterns and body shapes.[6] Loricariids are characterized by bony plates covering their body, similar to the bony plates in callichthyids (In Latin, lorica means corselet).[17] These fish exhibit a ventral suckermouth with papillae (small projections) on the lips. When present, the adipose fin usually has a spine at the forward edge.[2] These fish have, when they are present, a unique pair of maxillary barbels.[2][6] These fish have relatively long intestines due to their usually herbivorous or detrivorous diets.[2] The body is characteristically depressed in this family.[6] Taste buds cover almost the entire surface of the body and fin spines.[18] The length can range from 3 centimetres (1.2 in) in some Otocinclus to over 100 centimetres (39 in) in Panaque, Acanthicus, and Pterygoplichthys.[16]

One of the most obvious characteristics of the loricariids is the suckermouth. The modified mouth and lips allow the fish to feed, breathe, and attach to the substrate through suction. It was once believed that lips could not function as a sucker while respiration continued as the inflowing water would cause the system to fail; however, it has been demonstrated that respiration and suction can function simultaneously. Inflowing water passing under the sucker is limited to a thin stream immediately behind each maxillary barbel; the maxillae in loricariids support only small maxillary barbels and are primarily used to mediate the lateral lip tissue in which they are embedded, preventing failure of suction during inspiration. To achieve suction, the fish pressed its lips against the substrate and inflates its mouth, causing negative pressure.[19]

Also, unlike most other catfish, the premaxillae are highly mobile, and the lower jaws have evolved towards a medial position with the teeth pointed rostroventrally; these are important evolutionary innovations.[15] The fish rotates its lower and upper jaws to scrape the substrate. The lower jaws are most mobile.[19]

Loricariid catfishes have evolved several modifications of the digestive tract that function as accessory respiratory organs or hydrostatic organs. These complex structures would have been independently evolved a number of times. This includes an enlarged stomach in the Pterygoplichthyini, Hypostomus, and Lithoxus, a U-shaped diverticulum in Rhinelepini, and a ring-like diverticulum in Otocinclus. However, even loricariids with an unmodified stomach have a slight ability to breathe air.[20]

Considerable sexual dimorphism occurs in this family, most pronounced during the breeding season. For example, in Loricariichthys, the male has a large expansion of its lower lip, which it uses to hold a clutch of eggs.[18] Ancistrus males have snouts with fleshy tentacles.[18] In loricariids, odontodes develop almost anywhere on the external surface of the body and first appear soon after hatching; odontodes appear in a variety of shapes and sizes and are often sexually dimorphic, being larger in breeding males.[18] In most Ancistrini species, sharp evertible cheek spines (elongated odontodes) are often more developed in males and are used in intraspecific displays and combat.[18]

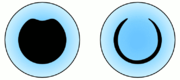

Unusually for bony fish, many species have a modified iris called an omega iris. The top part of the iris descends to form a loop which can expand and contract called an iris operculum; when light levels are high, the pupil reduces in diameter and the loop expands to cover the center of the pupil giving rise to a crescent shaped light transmitting portion.[21] This feature gets its name from its similarity to an upside-down Greek letter omega (Ω). The origins of this structure are unknown, but it has been suggested that breaking up the outline of the highly visible eye aids camouflage in what are often highly mottled animals.[21] Species in the tribe Rhinelepini are an exception among loricariids, having a normal, circular iris.[22] The presence or absence of the iris operculum can also be used for identification of species in the subfamily Loricariinae.[6]

Genetics

As of 2000, only 56 loricariid species have been cytogenically investigated.[4] It has been shown that 2n = 54 is the basal diploid number of chromosomes this family.[23] There is a wide variation in the chromosome number in this fish group, ranging from 2n = 36 in the Loricariinae, Rineloricaria latirostris, to 2n = 96 in a species of Upsilodus (Hemipsilichthys).[23] Most members of the Ancistrini and Pterygoplichthyini have 52 chromosomes.[4] Karyotypic evolution by means of centric fusions and centric fissions seems to be a common feature among loricariids; this is demonstrated by a higher number of biarmed chromosomes in species with lower diploid number and many uniarmed chromosomes in species with higher diploid numbers.[24] Studies conducted with representatives of some genera of Hypostominae showed that within this group, the diploid number ranges from 2n = 52 to 2n = 80. However, the supposed wide karyotypic diversity that the family Loricariidae or the subfamily Hypostominae would present is almost exclusively restricted to the genus Hypostomus, and the species from the other genera had a conserved diploid number.[11] It has been found in some species that there is a ZZ/ZW sex-determination system.[4][24]

Ecology

The suckermouth exhibited by these catfish allow them to adhere to objects in their habitats, even in fast-flowing waters.[6] The mouth and teeth also are adapted to feed on a variety of foods such as algae, invertebrates, and detritus.[6] Some species, notably the Panaque, are known for xylophagy, or the ability to digest wood.[25]

Most species of Loricariids are nocturnal animals. Some species are territorial, while others, such as Otocinclus, prefer to live in groups.[3]

Air-breathing is well known among many loricariids. The ability to breathe air is dependent on the risk of hypoxia faced by a species; torrent-dwelling species tend to have no ability to breathe air, while low-land, pool-dwelling species such as those of Hypostomus have a great ability to breathe air.[20] Pterygoplichthys are known for being kept out of water and sold alive in fish markets, surviving up to 30 hours out of water.[20] Loricariids are facultative air breathers; they will only breathe air if under stress and will only use their gills in situations when oxygen levels are high. The dry season is a likely time for this; there would be little food in the stomach, which would allow its use for air breathing.[20]

Loricariids exhibit a wide range of reproductive strategies, including cavity spawning, attachment of eggs on the underside of rocks, and egg-carrying.[18] Parental care is usually well-developed and the male guards the eggs and sometimes the larvae.[18] The eggs hatch after between 4 and 20 days, depending on the species.[3]

In the aquarium

Loricariids are popular aquarium fish, where they are often sold as "plecs", "plecos" or "plecostomus".[2] These fish are often purchased because of their algae-eating habits, though this role may not be carried out.[3] Most species are in fact detritivores. A great many species of Loricariids are also sold for their ornamental qualities, representing many body shapes and colors.

Most species of Loricariids are nocturnal and will shy away from bright light, appreciating some sort of cover to hide under throughout the day. As they often originate from habitats with fast-moving water, filtration should be vigorous.[3]

A number of species of Loricariids have been bred in captivity.[3]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Provenzano R., Francisco; Schaefer, Scott A.; Baskin, Jonathan N.; Royero-Leon, Ramiro (2003). "New, Possibly Extinct Lithogenine Loricariid (Siluriformes, Loricariidae) from Northern Venezuela" (PDF). Copeia (American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists) 2003 (3): 562–575. doi:10.1643/CI-02-160R1. http://www.bioone.org/archive/0045-8511/2003/3/pdf/i0045-8511-2003-3-562.pdf.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 Nelson, Joseph, S. (2006). Fishes of the World. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. ISBN 0471250317.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Fenner, Robert. "Loricariids". WetWebMedia.com. http://www.wetwebmedia.com/FWSubWebIndex/loricariids.htm. Retrieved 2007-05-03.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 de Oliveira, Renildo Ribeiro; Souza, Issakar Lima Souza; Venere, Paulo Cesar (2006). "Karyotype description of three species of Loricariidae (Siluriformes) and occurrence of the ZZ/ZW sexual system in Hemiancistrus spilomma Cardoso & Lucinda, 2003" (PDF). Neotropical Ichthyology 4 (1): 93–97. http://www.ufrgs.br/ni/vol4num1/vol4(1)p93.pdf.

- ↑ Linder, Shane. "What are L Numbers?". http://www.aquariacentral.com/articles/lnumbers.shtml.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 Covain, Raphael; Fisch-Muller, Sonia (2007). "The genera of the Neotropical armored catfish subfamily Loricariinae (Siluriformes: Loricariidae): a practical key and synopsis" (PDF). Zootaxa 1462: 1–40. http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/2007f/zt01462p040.pdf. Retrieved 2009-06-23.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 J. W. Armbruster. "Loricariid taxa list". http://www.auburn.edu/academic/science_math/res_area/loricariid/fish_key/TAXALIST/taxalist.html.

- ↑ Reis, Roberto E.; Pereira, Edson H.L.; Armbruster, Jonathan W. (2006). "Delturinae, a new loricariid catfish subfamily (Teleostei, Siluriformes), with revisions of Delturus and Hemipsilichthys". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 147 (2): 277–299. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2006.00229.x.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Ferraris, Carl J., Jr. (2007). "Checklist of catfishes, recent and fossil (Osteichthyes: Siluriformes), and catalogue of siluriform primary types" (PDF). Zootaxa 1418: 1–628. http://silurus.acnatsci.org/ACSI/library/biblios/2007_Ferraris_Catfish_Checklist.pdf. Retrieved 2009-06-23.

- ↑ Schaefer, Scott A. (2003). "Relationships of Lithogenes villosus Eigenmann, 1909 (Siluriformes, Loricariidae): Evidence from High-Resolution Computed Microtomography" (PDF). American Museum Novitates (American Museum of Natural History) 3401: 1–55. doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2003)401<0001:ROLVES>2.0.CO;2. http://www.bioone.org/archive/0003-0082/3401/1/pdf/i0003-0082-3401-1-1.pdf.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Alves, Anderson Luís; Oliveira, Claudio; Foresti (2005). "Comparative cytogenetic analysis of eleven species of subfamilies Neoplecostominae and Hypostominae (Siluriformes: Loricariidae)". Genetica 124 (2-3): 127–136. doi:10.1007/s10709-004-7561-4. PMID 16134327.

- ↑ Pereira, Edson H. Lopes (2005). "Resurrection of Pareiorhaphis Miranda Ribeiro, 1918 (Teleostei: Siluriformes: Loricariidae), and description of a new species from the rio Iguaçu basin, Brazil" (PDF). Neotropical Ichthyology 3 (2): 271–276. doi:10.1590/S1679-62252005000200004. http://www.ufrgs.br/ni/vol3num2/Artigo04p271-276lr.pdf.

- ↑ Werneke, David C.; Armbruster, Jonathan W.; Lujan, Nathan K.; Taphorn, Donald C. (2005). "Hemiancistrus guahiborum, a new suckermouth armored catfish from Southern Venezuela (Siluriformes: Loricariidae)" (PDF). Neotropical Ichthyology (Sociedade Brasileira de Ictiologia) 3 (4): 543–548. doi:10.1590/S1679-62252005000400012. http://www.ufrgs.br/ni/vol3num4%5CNI_v3n4p543-548lowr.pdf.

- ↑ Malabarba, Maria Claudia; Lundberg, John G. (2007). "A fossil loricariid catfish (Siluriformes: Loricarioidea) from the Taubaté Basin, eastern Brazil". Neotropical Ichthyology 5 (3): 263–270. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.14.8063. PMID 9525907.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Schaefer, Scott A.; Lauder, George V. (1986). "Historical Transformation of Functional Design: Evolutionary Morphology of Feeding Mechanisms in Loricarioid Catfishes". Systematic Zoology (Society of Systematic Biologists) 35 (4): 489–508. doi:10.2307/2413111. http://jstor.org/stable/2413111.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Quevedo, Rodrigo; Reis, Roberto E. (2002). "Pogonopoma obscurum: A New Species of Loricariid Catfish (Siluriformes: Loricariidae) from Southern Brazil, with Comments on the Genus Pogonopoma" (PDF). Copeia 2002 (2): 402–410. doi:10.1643/0045-8511(2002)002[0402:POANSO]2.0.CO;2. http://www.bioone.org/archive/0045-8511/2002/2/pdf/i0045-8511-2002-2-402.pdf.

- ↑ Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2007). "Loricariidae" in FishBase. May 2007 version.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 18.6 Sabaj, Mark H.; Armbruster, Jonathan W.; Page, Lawrence M. (1999). "Spawning in Ancistrus (Siluriformes: Loricariidae) with comments on the evolution of snout tentacles as a novel reproductive strategy: larval mimicry" (PDF). Ichthyol. Explor. Freshwaters 10 (3): 217–229. http://www.auburn.edu/academic/science_math/res_area/loricariid/fish_key/Ancistrus.pdf. Retrieved 2009-06-23.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Geerinckx, Tom; Brunain, Marleen; Herrel, Anthony; Aerts, Peter; Adriaens, Dominique (January 2007). "A head with a suckermouth : a functional-morphological study of the head of the suckermouth armoured catfish Ancistrus cf. triradiatus (Loricariidae, Siluriformes)" (PDF). Belg. J. Zool. 137 (1): 47–66. http://www.naturalsciences.be/institute/associations/rbzs_website/bjz/back/pdf/BJZ%20137(1)/Volume%20137(1),%20pp.%2047-66.pdf.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 "Modifications of the Digestive Tract for Holding Air in Loricariid and Scoloplacid Catfishes" (PDF). Copeia (3): 663–675. 1998. http://www.auburn.edu/academic/science_math/res_area/loricariid/fish_key/Air.pdf. Retrieved 2009-06-23.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Douglas, Ron H.; Collin, Shaun P.; Corrigan, Julie (2002-11-15). "The eyes of suckermouth armoured catfish (Loricariidae, subfamily Hypostomus): pupil response, lenticular longitudinal spherical aberration and retinal topography" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Biology (The Journal of Experimental Biology) 205 (22): 3425–3433. http://jeb.biologists.org/cgi/reprint/205/22/3425.

- ↑ Armbruster, Jonathan W. (1998). "Phylogenetic Relationships of the Suckermouth Armored Catfishes of the Rhinelepis Group (Loricariidae: Hypostominae)". Copeia 1998 (3): 620–636. doi:10.2307/1447792. http://jstor.org/stable/1447792.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Artoni, Roberto Ferreira; Bertollo, Luiz Antonio Carlos (2001). "Trends in the karyotype evolution of Loricariidae fish (Siluriformes)" (PDF). Hereditas 134 (3): 201–210. doi:10.1111/j.1601-5223.2001.00201.x. PMID 11833282. http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1601-5223.2001.00201.x.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Kavalco, KF; Pazza, R; Bertollo, LAC; Moreira-Filho, O (2005). "Karyotypic diversity and evolution of Loricariidae (Pisces, Siluriformes)" (PDF). Heredity 94 (2): 180–186. doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6800595. PMID 15562288. http://www.nature.com/hdy/journal/v94/n2/pdf/6800595a.pdf. Retrieved 2009-06-23.

- ↑ Nelson, J. A.; Wubah, D. A.; Whitmer, M. E.; Johnson, E. A.; Stewart, D. J. (1999). "Wood-eating catfishes of the genus Panaque: gut microflora and cellulolytic enzyme activities" (PDF). Journal of Fish Biology 54: 1069–1082. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1999.tb00858.x. http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1095-8649.1999.tb00858.x.

External links

- THE LORICARIIDAE by Dr. Jonathan Armbruster - useful website including a taxonomic key.

- Planet Catfish Catalogue of loricariid catfishes

- All Catfish Species Inventory page for Loricariidae