Lidocaine

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

| 2-(diethylamino)- N-(2,6-dimethylphenyl)acetamide |

|

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 137-58-6 73-78-9 (hydrochloride) |

| ATC code | N01BB02 C01BB01 D04AB01 S02DA01 C05AD01 |

| PubChem | CID 3676 |

| DrugBank | APRD00479 |

| ChemSpider | 3548 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C14H22N2O |

| Mol. mass | 234.34 g/mol |

| SMILES | eMolecules & PubChem |

| Synonyms | N-(2,6-dimethylphenyl)-N2,N2-diethylglycinamide |

| Physical data | |

| Melt. point | 68 °C (154 °F) |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 35% (oral) 3% (topical) |

| Metabolism | Hepatic, 90% CYP1A2-mediated |

| Half-life | 1.5–2 hours |

| Excretion | renal |

| Therapeutic considerations | |

| Pregnancy cat. | A(AU) B(US) |

| Legal status | Prescription Only (S4) (AU) ? (US) |

| Routes | IV, subcutaneous, topical |

| |

|

Lidocaine (pronounced /ˈlaɪdɵkeɪn/) (INN), xylocaine or lignocaine (/ˈlɪɡnɵkeɪn/) (former BAN) is a common local anesthetic and antiarrhythmic drug. Lidocaine is used topically to relieve itching, burning and pain from skin inflammations, injected as a dental anesthetic or as a local anesthetic for minor surgery.

Contents |

History

Lidocaine, the first amino amide-type local anesthetic, was first synthesized under the name xylocaine by Swedish chemist Nils Löfgren in 1943.[1] His colleague Bengt Lundqvist performed the first injection anesthesia experiments on himself.[1] It was first marketed in 1949. Etymology: from one of its many chemical names - [alpha-Diethylamino-2,6-dimethylacetani- ] - lide + ~ocaine.

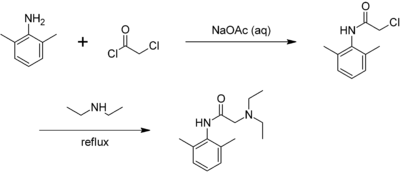

Preparation

Lidocaine may be prepared in two steps by the reaction of 2,6-xylidine with chloroacetyl chloride, followed by the reaction with diethylamine:[2]

Pharmacokinetics

Lidocaine is approximately 90% metabolized (de-ethylated) in the liver by CYP1A2 (and to a minor extent CYP3A4) to the pharmacologically-active metabolites monoethylglycinexylidide and glycinexylidide.

The elimination half-life of lidocaine is approximately 90–120 minutes in most patients. This may be prolonged in patients with hepatic impairment (average 343 minutes) or congestive heart failure (average 136 minutes).[3]

Pharmacodynamics

Anesthesia

Lidocaine alters signal conduction in neurons by blocking the fast voltage gated sodium (Na+) channels in the neuronal cell membrane, which are responsible for signal propagation[4]. With sufficient blockade, the membrane of the postsynaptic neuron will not depolarize and so fail to transmit an action potential, leading to its anaesthetic effects. Careful titration allows for a high degree of selectivity in the blockage of sensory neurons, whereas higher concentrations will also affect other modalities of neuron signaling.

Clinical use

Indications

Topical lidocaine has been shown to relieve postherpetic neuralgia (arising, for example, from shingles) in some patients, though there is not enough study evidence to recommend it as a first-line treatment.[5] It also has uses as a temporary fix for tinnitus. Although not completely curing the illness, it has been shown to reduce the effects by around two thirds.[6]

The efficacy profile of lidocaine as a local anesthetic is characterized by a rapid onset of action and intermediate duration of efficacy. Therefore, lidocaine is suitable for infiltration, block and surface anesthesia. Longer-acting substances such as bupivacaine are sometimes given preference for spinal and peridural anesthesias; lidocaine, on the other hand, has the advantage of a rapid onset of action. Adrenaline vasoconstricts arteries and hence delays the resorption of Lidocaine, almost doubling the duration of anaesthesia. For surface anesthesia several formulations are available that can be used e.g. for endoscopies, before intubations etc.

Lidocaine is also the most important class 1B antiarrhythmic drug: it is used intravenously for the treatment of ventricular arrhythmias (for acute myocardial infarction, digitalis poisoning, cardioversion or cardiac catheterization). However, a routine prophylactic administration is no longer recommended for acute cardiac infarction; the overall benefit of this measure is not convincing.

Lidocaine has also been efficient in refractory cases of status epilepticus.

Lidocaine has also proved effective in treating jellyfish stings, both numbing the affected area and preventing further nematocyst discharge [7]

Contraindications

Contraindications for the use of lidocaine include:

- Heart block, second or third degree (without pacemaker)

- Severe sinoatrial block (without pacemaker)

- Serious adverse drug reaction to lidocaine or amide local anaesthetics

- Concurrent treatment with quinidine, flecainide, disopyramide, procainamide (Class I antiarrhythmic agents)

- Prior use of Amiodarone hydrochloride

- Hypotension not due to Arrhythmia

- Bradycardia

- Accelerated idioventricular rhythm

- Pacemaker

Adverse drug reactions

Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are rare when lidocaine is used as a local anesthetic and is administered correctly. Most ADRs associated with lidocaine for anesthesia relate to administration technique (resulting in systemic exposure) or pharmacological effects of anesthesia, but allergic reactions only rarely occur.[8]

Systemic exposure to excessive quantities of lidocaine mainly result in central nervous system (CNS) and cardiovascular effects – CNS effects usually occur at lower blood plasma concentrations and additional cardiovascular effects present at higher concentrations, though cardiovascular collapse may also occur with low concentrations. CNS effects may include CNS excitation (nervousness, tingling around the mouth (also known as circumoral paraesthesia), tinnitus, tremor, dizziness, blurred vision, seizures) followed by depression, and with increasingly heavier exposure: drowsiness, loss of consciousness, respiratory depression and apnoea). Cardiovascular effects include hypotension, bradycardia, arrhythmias, and/or cardiac arrest – some of which may be due to hypoxemia secondary to respiratory depression.[9]

ADRs associated with the use of intravenous lidocaine are similar to toxic effects from systemic exposure above. These are dose-related and more frequent at high infusion rates (≥3 mg/minute). Common ADRs include: headache, dizziness, drowsiness, confusion, visual disturbances, tinnitus, tremor, and/or paraesthesia. Infrequent ADRs associated with the use of lidocaine include: hypotension, bradycardia, arrhythmias, cardiac arrest, muscle twitching, seizures, coma, and/or respiratory depression.[9]

Overdosage

Overdosage with lidocaine can be a result of excessive administration via topical or parenteral routes, accidental oral ingestion of topical preparations by children, accidental intravenous (rather than subcutaneous, intrathecal or paracervical) injection or prolonged use of subcutaneous infiltration anesthesia during cosmetic surgical procedures. These occurrences have often led to severe toxicity or death in both children and adults. Lidocaine and its two major metabolites may be quantitated in blood, plasma or serum to confirm the diagnosis in potential poisoning victims or to assist in the forensic investigation in a case of fatal overdosage. It is important in the interpretation of analytical results to recognize that lidocaine is often routinely administered intravenously as an antiarrhthymic agent in critical cardiac care situations.[10]

Insensitivity to lidocaine

Relative insensitivity to lidocaine runs in families. In hypokalemic sensory overstimulation, relative insensitivity to lidocaine has been described in people who also have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. In dental anesthesia, a relative insensitivity to lidocaine can occur for anatomical reasons due to unexpected positions of nerves. Some people with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome are insensitive to lidocaine.[11]

Dosage forms

Lidocaine, usually in the form of lidocaine hydrochloride, is available in various forms including:

- Injected local anesthetic (sometimes combined with epinephrine to reduce bleeding)

- Dermal patch (sometimes combined with prilocaine)

- Intravenous injection (sometimes combined with epinephrine to reduce bleeding)

- Intravenous infusion

- Nasal instillation/spray (combined with phenylephrine)

- Oral gel (often referred to as "viscous lidocaine" or abbreviated "lidocaine visc" or "lidocaine hcl visc" in pharmacology; used as teething gel)

- Oral liquid

- Topical gel (as with Aloe vera gels that include lidocaine) [12]

- Topical liquid

- Topical patch (lidocaine 5% patch is marketed as "Lidoderm" in the US (since 1999) and "Versatis" in the UK (since 2007 by Grünenthal))

- Topical aerosol spray

- Inhaled via a nebulizer

Additive in cocaine

Lidocaine is often added to cocaine as a diluent.[13] Cocaine numbs the gums when applied, and since lidocaine causes stronger numbness[14], users get the impression of high-quality cocaine when in actuality, the user is receiving a diluted product.[15]

Illegal uses

Lidocaine is not currently listed by the World Anti-Doping Agency as an illegal substance.[16]. Lidocaine is used as a adjuvant, adulterant, mimic and diluent to illegal street drugs (eg. cocaine). (See U.S. DEA web site).

Compendial status

- Japanese Pharmacopoeia 15

- United States Pharmacopeia 31 [17]

See also

- Lidocaine/prilocaine

Notes and references

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Nils Löfgren (1948). Xylocaine: a new synthetic drug.

- ↑ T. J. Reilly (1999). "The Preparation of Lidocaine". J. Chem. Ed. 76 (11): 1557. doi:10.1021/ed076p1557. http://jchemed.chem.wisc.edu/Journal/Issues/1999/Nov/abs1557.html.

- ↑ Thomson PD, Melmon KL, Richardson JA, et al. (1973). "Lidocaine pharmacokinetics in advanced heart failure, liver disease, and renal failure in humans". Ann. Intern. Med. 78 (4): 499–508. PMID 4694036.

- ↑ Catterall WA (2002). "Molecular mechanisms of gating and drug block of sodium channels". Novartis Found Symp 241: 206–32. doi:10.1002/0470846682.ch14. PMID 11771647.

- ↑ Khaliq W, Alam S, Puri N (2007). "Topical lidocaine for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD004846. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004846.pub2. PMID 17443559.

- ↑ http://newsvote.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/7175306.stm

- ↑ 17. Birsa LM, Verity PG, Lee RF, (2010). "Evaluation of the effects of various chemicals on discharge of and pain caused by jellyfish nematocysts". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology, Part C 151: 426-430. doi:10.1016/j.cbpc.2010.01.007.

- ↑ D Jackson, AH Chen, and CR Bennett (1994). "Identifying true lidocaine allergy". J Am Dent Assoc 125 (10): 1362–1366. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7844301.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Rossi S, editor. Australian Medicines Handbook 2006. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook; 2006. ISBN 0-9757919-2-3

- ↑ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 840-844.

- ↑ Grahame, Rodney; Grahame, R; Norris, P; Hopper, C (2005). "Local anaesthetic failure in joint hypermobility syndrome". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 98 (2): 84–85. doi:10.1258/jrsm.98.2.84. PMID 15684369.

- ↑ Solarcaine topical gel, July 27, 2009

- ↑ Naissa Prévide Bernardo, Maria Elisa Pereira Bastos Siqueira, Maria José Nunes de Paiva, Patrícia Penido Maia (2003). "Caffeine and other adulterants in seizures of street cocaine in Brazil". International Journal of Drug Policy 14 (4): 331–334. doi:10.1016/S0955-3959(03)00083-5. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6VJX-497HGRX-5/2/3b5f81654f1e907ceb3095b4b5207362.

- ↑ Howell, Kimberly. "Take a big-picture approach when dealing with corneal sensation". http://www.eyeplastics.org/topics/thyroid/thyroid_news/corneal_sensation.htm. Retrieved 2009-04-23. "Lidocaine is more potent, with rapid diffusion and penetration."

- ↑ 599 F.2d 635

- ↑ http://www.wada-ama.org/Documents/World_Anti-Doping_Program/WADP-Prohibited-list/WADA_Prohibited_List_2010_EN.pdf

- ↑ Revision Bulletin: Lidocaine and Prilocaine Cream–Revision to Related Compounds Test

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||