Lichfield

| City of Lichfield | |

City of Lichfield

|

|

| Population | 30,050 (Mid-2007 estimate) |

|---|---|

| OS grid reference | |

| Parish | Lichfield |

| District | Lichfield |

| Shire county | Staffordshire |

| Region | West Midlands |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LICHFIELD |

| Postcode district | WS13, WS14 |

| Dialling code | 01543 |

| Police | Staffordshire |

| Fire | Staffordshire |

| Ambulance | West Midlands |

| EU Parliament | West Midlands |

| UK Parliament | Lichfield |

| List of places: UK • England • Staffordshire | |

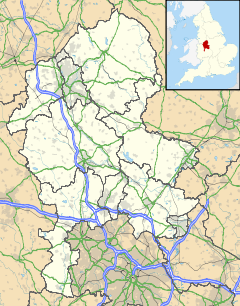

Lichfield (pronounced /ˈlɪtʃfiːld/) is a city and civil parish[1] in Staffordshire, England. One of seven civil parishes with city status in England, Lichfield is situated roughly 25 km (16 miles) north of Birmingham and 200 km (124 miles) northwest of London.

Lichfield is notable for its three-spired cathedral and as the birthplace of Samuel Johnson, the writer of the first authoritative Dictionary of the English Language. Today it still retains its old importance as an ecclesiastical centre, but its industrial and commercial development has been relatively small; the centre of the city thus retains an essentially old-world character. The construction of a major shopping and leisure complex, which will transform the city centre, was due to begin in 2009, however, due to the global economic downturn, the construction has been delayed.[2] In July 2009, the Staffordshire Hoard, the largest hoard of Anglo-Saxon gold ever found in Britain was discovered in a field near Lichfield.

The population of the city according to the 2001 census is 27,900 and the wider Lichfield district has a population of 93,237. In mid-2007, the city had an estimated population of 30,050 (from the estimated headcounts[3] of its electoral wards Boley Park, Chadsmead, Curborough, Leomansley, St.Johns and Stowe).

Etymology

Legend has it that a thousand Christians were martyred in Lichfield around AD 300, during the reign of the Roman Emperor Diocletian, and that the name 'Lichfield' actually means 'field of the dead'. There is however, no evidence to support this legend.[4] At Wall, 3 miles (5 km) to the south of the present city, there was a Romano-British village called Letocetum from the British (Celtic) for "grey wood", from which the first half of the name Lichfield is derived.[5] The second part of the name is derived from the Old English "feld", meaning 'open country'. In that sense 'Lichfield' would be 'common pasture in grey wood', 'grey' perhaps referring to varieties of tree prominent in the landscape, such as ash and elm.[6]

History

Early history: Religious centre of Mercian kings

The early history of Lichfield is obscure. The first authentic record of Lichfield occurs in Bede's history, where it is called Licidfelth and mentioned as the place where St Chad fixed the episcopal see of the Mercians in 669. The first Christian king of Mercia, King Wulfhere donated land at Lichfield for Chad to build a monastery. It was because of this that the ecclesiastical centre of the Diocese of Mercia became settled at Lichfield, which was approximately 3 miles north of the seat of the Mercian kings at Tamworth. The first cathedral to be built on the present site was in 700 when Bishop Hedda built a new church to house the bones of St Chad which had become a sacred shrine to many pilgrims when he died in 672. The burial in the cathedral of the kings of Mercia, King Wulfhere in 674 and King Ceolred in 716, further increased the prestige of Lichfield.[7] In 786 Offa, King of Mercia, raised Lichfield to the dignity of an archbishopric, with authority over all the bishops from the Humber to the Thames. However after King Offa's death in 796, Lichfield's power waned and in 803 the primacy was restored to Canterbury by Pope Leo III after only 16 years. The Historia Britonum lists the city as one of the 28 cities of Britain around AD 833.

9th century: Viking invaders and decline

During the 9th century, the Kingdom of Mercia was devastated by the Vikings from Denmark. Lichfield itself was unwalled and the cathedral was despoiled, so Bishop Peter moved the see to the fortified and wealthier Chester in 1075. His successor, Robert de Limesey, transferred it to Coventry, but it was eventually restored to Lichfield in 1148. Work began on the present Gothic cathedral in 1195. At the time of the Domesday survey, Lichfield was held by the bishop of Chester, where the see of the bishopric had been moved 10 years earlier; Lichfield was listed as a small village. The lord of the manor was the bishop of Chester until the reign of Edward VI.

Middle Ages: New town laid out by Bishop Clinton

Bishop Clinton was responsible for transforming the scattered settlements to the south of Minster Pool into the ladder plan streets we recognise today. Market Street, Wade Street, Bore Street and Frog Lane linked Dam Street, Conduit Street and Bakers Lane on one side with Bird Street and St John Street on the other. Bishop Clinton also fortified the cathedral close, enclosed the town with a bank and ditch, and gates were set up where roads into the town crossed the ditch.[7] In 1291 Lichfield was severely damaged by a fire, which destroyed most of the town, however the Cathedral and Close survived unscathed.[8] In 1387 Richard II gave a charter for the foundation of the gild of St Mary and St John the Baptist; this gild functioned as the local government, until its dissolution by Edward VI, who incorporated the town in 1548.

16th century: Reformation and martyrs

Henry VIII had a dramatic affect on Lichfield. The Reformation brought the disappearance of pilgrim traffic following the destruction of St Chad's shrine in 1538 which was a major loss to the city's economic prosperity. That year too the Franciscan friary was dissolved, the site becoming a private estate. Further economic decline followed the outbreak of plague in 1593, which resulted in the death of over a third of the entire population.[9]

Three people were burned at the stake for heresy under Mary I. The last person in England to be burnt at the stake for heresy was in Lichfield. Edward Wightman from Burton upon Trent was burnt at the stake in the Market Place on 11 April 1612 for refusing to recant his Baptist beliefs.

17th century: Destruction of the Civil War

In the English Civil War, Lichfield was divided. The cathedral authorities, with a certain following, were for the king, but the townsfolk generally sided with the Parliament. This led to the fortification of the close in 1643. Lichfield's position as a focus of supply routes had an important strategic significance during the war, and both forces were anxious for control of the city. Lord Brooke, notorious for his hostility to the church, led an assault against it, but was killed by a deflected bullet on St Chad's day, an accident welcomed as a miracle by the Royalists. The close yielded and was retaken by Prince Rupert of the Rhine in this year; but on the breakdown of the king's cause in 1646 it again surrendered. The cathedral suffered extensive damage from the war, including the complete destruction of the central spire. It was subsequently restored at the end of the Commonwealth period under the supervision of Bishop Hacket, and thanks in part to the generosity of King Charles II.

18th century: Thriving coaching city and cultural centre

Lichfield started to develop a lively coaching trade as a stop-off on the busy route between London and Chester from the 1650s onwards, making it Staffordshire's most prosperous town. By the start of the 18th century the city thrived as a busy coaching city on the main route to the northwest and Ireland. It also became a centre of great intellectual activity being the home of many famous people including Samuel Johnson, David Garrick, Erasmus Darwin and Anna Seward, this prompted Johnson's remark that Lichfield was "a city of philosophers". In the 1720s Daniel Defoe described Lichfield as 'a fine, neat, well-built, and indifferent large city', the principal town in the region after Chester.[10] An infantry regiment of the British Army was formed at Lichfield in 1705 by Col. Luke Lillingstone in the King's Head pub in Bird Street. In 1751 it became the 38th regiment of foot and in 1783 the 1st Staffordshire Regiment; after reorganization in 1881 it became the 1st battalion of the South Staffordshire Regiment.[10]

19th century: Industrial Revolution and decline

The arrival of the Industrial Revolution and the railways in the 19th century signaled the end of Lichfield's position as an important staging post for coaching traffic. Whilst the industrial development at nearby Birmingham exploded, along with its population, Lichfield remained largely unchanged in character.

20th century: World War II and post-War expansion

The first council houses were built in the Dimbles area of the city in the 1930s. The outbreak of World War II brought over 2000 evacuees from industrialised areas. However due to the lack of heavy industry in the city, Lichfield escaped lightly, although there were air raids in 1940 and 1941 and 3 Lichfeldians were killed. Just outside the city Wellington Bombers flew out of Fradley Aerodrome which was known as RAF Lichfield. After the war the council built many new houses in the 1960s including some high-rise flats, the late 70s and early 80s brought a large housing estate at Boley Park in the east of the city. The city's population tripled between 1951 and the late 1980s. Today the city continues to expand; to the west, a new area of housing has been under development for a number of years which has swelled the city's population by some 3,000.

21st century

Plans have been approved for a major new £100 million shopping and leisure complex, at Friarsgate, opposite Lichfield City Station. Friarsgate garage, Lichfield's multi-storey car park, police station, bus station and public toilets will all be demolished to make way for 22,000 square metres of retail space and 2,000 square metres designated for leisure facilities. It has been announced that this will consist of a flagship Debenhams department store, a six-screen cinema, a hotel, 37 individual shops and 56 apartments.[2] However, due to the global economic downturn, the construction has been delayed. In July 2009, The Staffordshire Hoard the largest collection of Anglo-Saxon gold ever found was discovered in a field near Lichfield.

Places of Interest

- Lichfield Cathedral - England's only medieval Cathedral with three spires. It is also the only medieval cathedral in Europe with three spires. The present building was started in 1195, and completed by the building of the Lady Chapel in the 1330s. It replaced a Norman building begun in 1085 which had replaced one, or possibly two, Saxon buildings from the seventh century. There is currently work taking place on the stone structure and glass windows.

- The Samuel Johnson Birthplace Museum - A museum to Samuel Johnson's life, work and personality.

- Erasmus Darwin House - Home to Erasmus Darwin, the house was restored to create a museum which opened to the public in 1999.

- The Lichfield Heritage Centre - in the market square, an exhibition of 2,000 years of Lichfield's history.

- The Bishop's Palace - Built in 1687, and a theological college built in 1837 are adjacent to the Cathedral.

- Milley's Hospital - Located on Beacon Street, it dates back to 1504 and was a women's hospital.

- Hospital of St John Baptist without the Barrs, Lichfield - A distinctive tudor building with a row of eight brick chimneys. This was built outside the city walls (barrs) to provide accommodation for travellers arriving after the city gates were closed. It now provides home for retired gentlemen and has an adjacent Chapel.

- The Church of St Chad - An 12th century church though extensively restored; on its site St Chad is said to have occupied a hermit's cell.

- St Michaels on Greenhill - Overlooking the city the medieval churchyard is one of the largest in the country at 9 acres.

- Christ Church, Lichfield - an outstanding example of Victorian ecclesiastical architecture and a grade II* listed building.

- The Market Square - In the centre of the city the square contains two statues, one of Samuel Johnson overlooking the house in which he was born, and one of his great friend and biographer, James Boswell.

- Beacon Park - A public park in the centre of the city.

- Wall Roman Site - The remains of a Roman settlement, 1 mile south of the city.

- Staffordshire Regiment Museum - 2.5 miles south west of the city in Whittington, the museum covers the regiment's history, activities and members, and include photographs, uniforms, weapons, medals, artifacts, memorabilia and regimental regalia. Outdoors is a replica trench from World War I, and several armoured fighting vehicles.

- National Memorial Arboretum - 4 miles north east of the city in Alrewas, the arboretum is a national site of remembrance and contains many memorials to the armed services.

- Cannock Chase - A designated Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, is 5 miles north west of the city. It comprises a mixture of natural deciduous woodland, coniferous plantations and open heathland. There are a number of visitor centres, museums and waymarked paths, including the Heart of England Way and the Staffordshire Way.

- Shugborough Hall - On Cannock Chase's north-eastern edge, the ancestral home of the Earls of Lichfield.

Famous Lichfeldians

- Joseph Addison (1672–1719) — Politician and writer

- Richard Allinson (born 1958) — Broadcaster

- Elias Ashmole (1617–1692) — Founder of Ashmolean Museum and advisor to Charles II

- Helen Baxendale (born 1970) — Actress

- Sian Brooke (born 1980) — Actress

- Adam Christodoulou (born 1989) — Racing driver, 2008 British Formula Renault Champion, 2009 Star Mazda Champion.

- Erasmus Darwin (1731–1802) — Scientist, inventor and literary man, grandfather of Charles Darwin

- Siobhan Dillon (born 1984) — Singer and actress

- Richie Edwards (born 1974) — Bassist with rock bands The Darkness and Stone Gods

- John Floyer (1649–1734) — English physician and author of the 18th century

- Phil Ford — Writer

- Bryn Fowler (born 1982) — Bassist and backing vocalist in the band The Holloways

- David Garrick (1717–1779) — Famous actor of the 18th century

- St. Edmund Gennings (1567–1591) — Jesuit priest and martyr

- David Charles Manners (born 1965) — Theatre designer, author and charity founder

- Samuel Johnson (1709–1784) — 18th century writer of the first authoritative English Dictionary

- Robert Rock (born 1977) - Golfer

- Anna Seward (1747–1809) — Romantic poet, memorialist and letter writer

Governance

Local government

Historically the Bishop of Lichfield had authority over the city. It wasn't until 1548 with Edward VI's charter that Lichfield had anything like a secular government. As a reward for the support given to Mary I by the bailiffs and citizens during the duke of Northumberland's attempt to prevent her accession, the queen issued a new charter in 1553, confirming the 1548 charter and in addition granting the city its own sheriff. The same charter made Lichfield a county separate from the rest of Staffordshire. It remained so until 1888.

Today, the City Council has 28 members who are elected every four years. The Mayor is the civic head of the Council and chairs Council meetings. The Deputy Mayor undertakes the Mayor's duties in the absence of the Mayor. The Council also appoints a Leader of Council to be the main person responsible for leadership of the Council's political and policy matters. The Council is also one of only 15 towns and cities in England and Wales which appoints a Sheriff.[11]

Members of Parliament

The Lichfield constituency sent two members to the parliament of 1304 and to a few succeeding parliaments, but the representation did not become regular until 1552; in 1867 it lost one member, and in 1885 its representation was merged in that of the county.[10]

The current Member of Parliament for Lichfield is the Conservative Michael Fabricant, who has been MP for Lichfield since 1997. Fabricant was first elected at the 1992 general election for Mid Staffordshire, regaining the seat for the Conservatives following Sylvia Heal's victory at the 1990 by-election. He took the seat with a majority of 6,236 and has remained a Member of Parliament since. The Mid Staffordshire seat was abolished at the 1997 general election, but Fabricant contested and won the Lichfield constituency, which partially replaced it, by just 238 votes. He has remained the Lichfield MP since, increasing his majority to 4,426 in the 2001 general election and to 7,080 in 2005. In the 2010 general election Fabricant's majority increased to two and a half times his 2005 majority, now standing at 17,683.

Economy

Lichfield's wealth grew along with its importance as an ecclesiastical centre. The original settlement prospered as the place where pilgrims gathered to worship at the shrine of St Chad, this practice continued up until the Reformation when the shrine was destroyed.

In the Middle Ages, the main industry in Lichfield was making woollen cloth. There was also a leather industry in Lichfield. Much of the surrounding area was open pasture and there were many surrounding farms.

In the 18th century, Lichfield became a busy coaching centre, there was little industry, the main source of wealth to the city coming from the money generated by its many visitors. The invention of the railways saw the decline in coach travel and with it came the decline in Lichfield's prosperity.

By the end of the 19th century, brewing was the principal industry, and in the neighbourhood were large market gardens which provided food for the growing populations of nearby Birmingham and the Black Country.

Today there are a number of light industrial areas predominantly in the east of the city, not dominated by any one particular industry. The district is famous for two local products: Armitage Shanks, manufacturers of baths/bidets and showers, and Arthur Price of England, master cutlers and silversmiths. Many residents commute to Birmingham.

It is predicted that once completed, the new Friarsgate retail and leisure development could attract 11,000 more visitors to the city every month, generating annual sales of around £61 million and creating hundreds of jobs in the city.[12]

Demographics

At the time of the 2001 census, the population of the City of Lichfield was 27,900. Lichfield is 98.1% white and 79% Christian. 56.7% of the population over 16 were married. 63.2% was employed and 16% of the people were retired. All of these figures were higher than the national average.[13]

| Population growth of the City of Lichfield since 1685 | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1685 | 1781 | 1801 | 1831 | 1901 | 1911 | 1951 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2001 | |||||||||

| Population | 3,040 | 3,555 | 4,840 | 6,252 | 7,900 | 8,616 | 10,260 | 14,090 | 22,660 | 25,400 | 28,666 | 27,900 | |||||||||

Culture

The Garrick Theatre was opened in 2003 replacing the Civic Hall, which was built in the 1970s. Each year in July The Lichfield Festival takes place, based primarily around the cathedral and the Garrick Theatre, it is celebration of classical music, dance, drama, film, jazz literature, poetry, visual arts and world music.[14] Since 1995 the Festival has incorporated a Medieval Market, taking place in the Cathedral Close.

Once every three years, The Lichfield Mystery Play cycle is performed in the Cathedral, the Market Place and on Stowe Fields. It is a cycle of 26 medieval plays involving nearly 1000 people, making it one of the largest community arts events in Europe.[15]

In 2009 the first Inspire Film Festival took place at the Garrick theater, created by a group of local media students. The event featured short films and documentaries from students all over the country.

The Lichfield Bower takes place on Spring Bank Holiday Monday, it dates back to the Middle Ages, when the townsfolk, after fulfilling their duty of attendance at the Court of Arraye, were given the rest of the day as holiday. A procession of marching bands and carnival floats makes its way through the city, where the Bower Queen is crowned outside the Guildhall at noon. There is also a fun fair in the city centre, and a fair and jamboree in Beacon Park.

The Lichfield Real Ale, Jazz & Blues Festival takes place in June each year.

The Bloodstock Open Air heavy metal music festival takes place every year at Catton Hall, approximately 7 miles outside of Lichfield.

Sport

Historically rugby was more popular in the city than football, this was largely due to the fact that it was the main sport at Lichfield Grammar School. However, both sports have remained at amateur level. Lichfield Rugby Union Football Club was founded in 1874. As of 2008-09 season they play in the Midlands 3 West (North) League. The team plays at Cooke Fields located on the road to Whittington village, behind the Horse and Jockey public house. The club moved there in the 1980s after their former home was sold for housing.

Lichfield City Football Club (formerly known as Beacon Park F.C. until June 2006) played in the Burton & District League until 2008. Following a successful season where goals from Adam Eccles and Simon Deeley saw the side win the Memorial cup. On the back of this success the club gained entrance to the Midland Football Combination. Lichfield gained promotion from the third division in their first full season and narrowly missed out on back to back promotions in the 2009/2010 season. The 1st team play at Brownsfield Park next the new Lichfield City FC Social Club (formerly known as Enots). LCFC are a FA Charter Community club with teams from under 7's to Adults.

Lichfield Diamonds LFC is at the forefront of girls football in Staffordshire, being the first all female club to achieve Charter Standard Status. The team plays at the Collins Hill Sports Ground.

Lichfield Cricket Club is a cricket team currently playing in the Third Division of the Birmingham and District Premier League. They also play at the Collins Hill Sports Ground.

Lichfield Archers were reformed over 40 years ago. The club shoot at their indoor and outdoor ranges at Christian Fields where they have a 20 yard indoor range and a 100 yard outdoor range.

Education

In addition to numerous Primary schools Lichfield has three secondary schools:

- King Edward VI School (formerly Lichfield Grammar School)

- The Friary School

- Nether Stowe High School

Additionally, there is the Cathedral School, a co-educational independent school for ages 3 to 18, based in the Cathedral Close and Longdon.

The Lichfield campus of Staffordshire University is located on The Friary. This campus facility was opened in 1998.

There is a DfES Approved Independent Special School for dyslexic children at Maple Hayes Dyslexia School, Abnalls Lane.

Suburbs

Boley Park | Chadsmead | Christchurch | Curborough | The Dimbles | Leomansley | Nether Stowe | Sandfields | Stowe | Streethay

Nearby places

Alrewas | Armitage | Birmingham | Brownhills | Burntwood | Burton-on-Trent | Cannock | Cannock Wood | Elford | Fradley | Gentleshaw | Hammerwich | Kings Bromley | Rugeley | Shenstone | Stafford | Sutton Coldfield | Tamworth | Uttoxeter | Wall | Weeford | Whittington

Twinnings

The City of Lichfield is twinned with:

Limburg an der Lahn, Germany

Limburg an der Lahn, Germany Sainte-Foy-lès-Lyon, France.

Sainte-Foy-lès-Lyon, France.

Transport

Lichfield is served by two railway stations, Lichfield City and Lichfield Trent Valley, both built by the London and North Western Railway. These stations are now on the Cross-City Line to Redditch via Birmingham. Additionally, Trent Valley station is on the West Coast Main Line with hourly direct semi-fast services to Euston, and also to Stafford, Stoke and Crewe, supplemented by occasional fast services.

Despite being north of Birmingham, trains between Lichfield Trent Valley and London Euston can take as little as 1 hour 9 minutes.

See also

- Lichfield Cathedral

- The Lichfield Festival

- Letocetum

- Bishops of Lichfield

- The Lichfield Gospels

- Earl of Lichfield

- Lichfield Cricket Club

- Lichfield Canal

- Garrick Theatre

- Heart of England Way

- Lichfield bower

- Lichfield Rugby Union Football Club

- RAF Lichfield

- Staffordshire Hoard

References

- ↑ "Names and codes for Administrative Geography". Office for National Statistics. 31 December 2008. http://www.ons.gov.uk/about-statistics/geography/products/geog-products-area/names-codes/administrative/index.html. Retrieved 15 September 2009.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "New Friarsgate development gets delayed due to 'credit crunch'". icLichfield. http://iclichfield.icnetwork.co.uk/news/localnews//tm_headline=credit-squeeze-delays-friarsgate&method=full&objectid=22250839&siteid=108911-name_page.html. Retrieved 20 November 2008.

- ↑ Mid-2007 Quinary Estimates for 2009 wards (experimental) at "Ward mid-year population estimates for England and Wales (experimental)". Office for National Statistics. http://www.statistics.gov.uk/statbase/Product.asp?vlnk=13893. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

- ↑ "Explaining the origin of the 'field of the dead' legend". British History Online. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=42340. Retrieved 20 November 2008.

- ↑ "English Place Name Society Database at Nottingham University". Nottingham.ac.uk. http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/~cczappdv/epnnewmap/detailpop.php?placeno=9823. Retrieved 2010-07-17.

- ↑ [From: 'Lichfield: The place and street names, population and boundaries ', A History of the County of Stafford: Volume 14: Lichfield (1990), pp. 37-42. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=42340 Date accessed: 20 July 2009.]

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 From: 'Lichfield: History to c.1500', A History of the County of Stafford: Volume 14: Lichfield (1990), pp. 4-14. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=42336 Date accessed: 24 July 2009.

- ↑ "Brief History of Lichfield". Local Histories. http://www.localhistories.org/lichfield.html. Retrieved 20 November 2008.

- ↑ "'Lichfield: From the Reformation to c.1800', A History of the County of Stafford: Volume 14: Lichfield (1990), pp. 14-24.". British History Online. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=42337. Retrieved 22 November 2008.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 From: 'Lichfield: From the Reformation to c.1800', A History of the County of Stafford: Volume 14: Lichfield (1990), pp. 14-24. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=42337 Date accessed: 24 July 2009.

- ↑ "Lichfield City Council Functions". Lichfield.gov.uk. http://www.lichfield.gov.uk/cc.ihtml. Retrieved 2010-07-17.

- ↑ "Economic benefits of new development to Lichfield". icLichfield. http://iclichfield.icnetwork.co.uk/news/localnews//tm_headline=credit-squeeze-delays-friarsgate&method=full&objectid=22250839&siteid=108911-name_page.html. Retrieved 20 November 2008.

- ↑ "Statistics". Lichfield. http://www.lichfield.gov.uk/cc-statistics.ihtml. Retrieved 2010-07-17.

- ↑ "About The Lichfield Festival". Lichfield Festival. http://www.lichfieldfestival.org/2008/content/view/25/40/. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ↑ "About The Lichfield Mysteries". http://www.lichfieldmysteries.co.uk/. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

External links

- Lichfield City Council

- Lichfield District Council

- Visit Lichfield - Travel and Tourism body

- Lichfield Arts

- Lichfield information and accommodation

|

||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||