Book of Leviticus

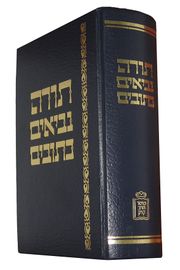

Leviticus (Greek: Λευιτικός, "relating to the Levites") or Vayikra (Hebrew: ויקרא, literally "and He called", Biblical Hebrew: Wayiq'ra) is the third book of the Hebrew Bible, and the third of five books of the Torah (or Pentateuch).

Leviticus contains laws and priestly rituals, but in a wider sense is about the working out of God's covenant with Israel set out in Genesis and Exodus—what is seen in the Torah as the consequences of entering into a special relationship with God (specifically, Yahweh). These consequences are set out in terms of community relationships and behaviour.

The first 16 chapters and the last chapter make up the Priestly Code, with rules for ritual cleanliness, sin-offerings, and the Day of Atonement, including Chapter 12, which mandates male circumcision. Chapters 17–26 contain the Holiness Code, including the injunction in chapter 19 to "love one's neighbor as oneself" (the Great Commandment). The book is largely concerned with "abominations", largely dietary and sexual restrictions. The rules are generally addressed to the Israelites, except for several prohibitions applied equally to "the strangers that sojourn in Israel."

According to Jewish and Christian tradition, God dictated the Book of Leviticus to Moses as He did the other books of the Bible.[1] However, modern biblical scholars believe Leviticus to be almost entirely from the priestly source (P), marked by emphasis on priestly concerns, composed c 550–400 BCE, and incorporated into the Torah c 400 BCE.[2]

Contents |

Title

In Hebrew the book is called Vayikra (Hebrew: ויקרא) literally "and He called",[3] from the first word of the Hebrew text, in line with the other four books of the Greek in the 3rd century BCE to produce the Septuagint, the name given was biblion to Levitikon (Greek: βιβλίον το Λευιτικόν), meaning "book of the Levites". This was in line with the Septuagint use of subject themes as book names. The Latin name became Liber Leviticus, from which the English name is derived. These names are somewhat misleading, as the book makes a very strong distinction between the priesthood, descended from Aaron, and mere Levites.

Summary

|

Part of a series

of articles on the |

|---|

| Tanakh (Books common to all Christian and Judaic canons) |

| Genesis · Exodus · Leviticus · Numbers · Deuteronomy · Joshua · Judges · Ruth · 1–2 Samuel · 1–2 Kings · 1–2 Chronicles · Ezra (Esdras) · Nehemiah · Esther · Job · Psalms · Proverbs · Ecclesiastes · Song of Songs · Isaiah · Jeremiah · Lamentations · Ezekiel · Daniel · Minor prophets |

| Deuterocanon |

| Tobit · Judith · 1 Maccabees · 2 Maccabees · Wisdom (of Solomon) · Sirach · Baruch · Letter of Jeremiah · Additions to Daniel · Additions to Esther |

| Greek and Slavonic Orthodox canon |

| 1 Esdras · 3 Maccabees · Prayer of Manasseh · Psalm 151 |

| Georgian Orthodox canon |

| 4 Maccabees · 2 Esdras |

| Ethiopian Orthodox "narrow" canon |

| Apocalypse of Ezra · Jubilees · Enoch · 1–3 Meqabyan · 4 Baruch |

| Syriac Peshitta |

| Psalms 152–155 · 2 Baruch · Letter of Baruch |

|

|

The book is generally considered to consist of two large sections, both of which contain several mitzvot (commandments).

The first part Leviticus 1–16, and Leviticus 27, constitutes the main portion of the Priestly Code, which describes the details of rituals, and of worship, as well as details of ritual cleanliness and uncleanliness. Within this section are:

- Laws regarding the regulations for different types of sacrifice (Leviticus 1–7):

- The practical application of the sacrificial laws, within a narrative of the consecration of Aaron and his sons (Leviticus 8–10)

- Aaron's first offering for himself and the people (Leviticus 8)

- The incident in which "strange fire" is brought to the Tabernacle by Aaron's sons Nadav and Avihu, leading to their death directly at the hands of God for doing so (Leviticus 9–10)

- Laws concerning purity and impurity (Leviticus 11–16)

- Laws about clean and unclean animals (Leviticus 11)

- Laws concerning ritual cleanliness after childbirth (Leviticus 12)

- Laws concerning tzaraath of people, and of clothes and houses, often translated as leprosy, and mildew, respectively (Leviticus 13–14)

- Laws concerning bodily discharges (such as blood, pus, semen, etc.) and purification (Leviticus 15)

- Laws regarding a day of national atonement, Yom Kippur (Leviticus 16)

- Laws concerning the commutation of vows (Leviticus 27)

The second part, Leviticus 17–26, is known as the Holiness Code, and places particular, and noticeable, emphasis on holiness, and the holy; it contains commandments intended not just for the priests but for the whole congregation.[4] It is notably more than a miscellany of laws. Within this section are:

- Laws concerning idolatry, the slaughter of animals, dead animals, and the consumption of blood (Leviticus 17)

- Laws concerning sexual conduct—incest, bestiality, same-sex relationships among men, laws concerning sorcery, and Moloch (Leviticus 18, and also Leviticus 20, in which penalties are given)

- Laws concerning molten gods, peace-offerings, scraps of the harvest, fraud, the deaf, blind, elderly, and poor, poisoning the well, hate, sex with slaves, self harm, shaving, tattoos, prostitution, sabbaths, sorcery, familiars, strangers, and just weights and measure (Leviticus 19)

- Laws concerning priests/the Sons of Aaron and their conduct, and possible prohibiting factors of being a priest such as prohibitions against the disabled, the permanently ill (anyone who: suffers from dwarfism, has poor eyesight, is hunchbacked, has damaged testicles, has a flat nose, etc.), and the superfluously blemished. Similar requirements are issued for animals that are to be sacrificed. (Leviticus 21–22)

- Laws concerning the observation of the annual feasts, and the sabbath, (Leviticus 23)

- Laws concerning the altar of incense (Leviticus 24:1–9)

- The case law lesson of a blasphemer being stoned to death, and other applications of the death penalty (Leviticus 24:10–23), including anyone having "a familiar ghost or spirit", a child insulting its parents (Leviticus 20), and a special case penalty for prostitution (Leviticus 21)

- Laws concerning the Sabbath, Jubilee years and slavery. (Leviticus 25).

- A hortatory conclusion to the section, giving promises regarding obedience to these commandments, and warnings and threats for those that might disobey them, including sending wild animals to devour their children. (Leviticus 26:22)

These ordinances, in the book, are said to have been delivered in the space of a month, specifically the first month of the second year after the exodus. A major Chiastic structure runs through practically all of this book.[5]

Structure and composition

According to traditional belief, Leviticus is the word of Yahweh, dictated to Moses from the Tent of Meeting before Mount Sinai. Since the 19th century, scholars have regarded Leviticus as being almost entirely a product of the priestly source (more recent scholarship prefers to refer to a "priestly school" of editors rather than a single priestly source), originating amongst the Aaronid priesthood circa 550–400 BCE; however, the dating of Leviticus is still widely disputed among scholars, and significant schools of thought argue either a pre-exilic, exilic, or post-exilic dating.

Leviticus consists of several layers of laws. The base of this accretion is the Holiness Code (chapters 17–26), regarded as an early independent document related to the Covenant Code presented earlier in the Bible. Wellhausen regarded the Priestly source as a later, rival, version of the stories contained within JE (a hypothetical intermediate source text of the Torah), the Holiness Code thus being the law code that the priestly source presented as being dictated to Moses at Sinai, in the place of the Covenant Code. Different writers inserted laws, some from earlier independent collections. These additional laws, in the views of those who follow Wellhausen's theories, are those that subsequently formed the Priestly Code, and thus the other portion of Leviticus. It also concerns the laws of the land, and of the seas.

Themes

Leviticus defines the most important rituals of ancient Israel, from sacrifice to cleanliness, the holy days to the calendar, birth and death. Gordon Wenham, quoting the early 20th century anthropologist Monica Wilson, points out that ritual is the key to understanding a society's central values; it makes up the markers by which a group of people recognise themselves as a group, and distinguish themselves from their neighbours.[6]

Leviticus in subsequent tradition

Judaism

Leviticus constitutes a major source of Jewish law. In Talmudic literature, there is evidence that this is the first book of the Tanakh taught in the Rabbinic system of education in Talmudic times. A possible reason may be that, of all the books of the Torah, Leviticus is the closest to being purely devoted to mitzvot and its study thus is able to go hand-in-hand with their performance.

There are two main Midrashim on Leviticus—the halakhic one (Sifra) and a more aggadic one (Vayikra Rabbah).

Christianity

Various Christian denominations have differing views of the relevance of the Levitical code to Christian conduct (see Law and Gospel). Most Christians do not consider themselves to be bound by the Levitical purity code itself. Many Christians, however, feel that certain moral aspects of the law still apply, such as the sexual morals of Chapter 18. Other groups such as the Seventh-day Adventist Church still attempt to follow some aspects of the dietary code of chapter 11. Theological arguments for Christianity's freedom from the law are largely based on passages such as Paul's 1 Corinthians 10:23–26, which permits believers to "eat anything sold in the meat market, without raising questions of conscience". The Letter to the Hebrews gives a theological justification for this view: it views Jesus as the perfect High Priest, "entering heaven not with the blood of bulls and goats (i.e., the sacrificial rules set out in Leviticus), but with his own blood"; and whereas the Jewish High Priest offered sacrifices continually and was permitted to enter the Holy of Holies only once a year, "Jesus offered just one sacrifice and is seated at God's right hand continually making intercession for his people." Similarly, the Gospel of Matthew 27:51 and Gospel of Mark 15:38 speak of the veil separating the holy of holies from the outer courtyard being torn in two when Jesus dies. This has been interpreted as symbolizing that God is now directly accessible. Most radically of all, the Jewish food laws, which symbolize the unique status of the Jews as the only people of God, are explicitly abrogated in Matthew 15:1–20 and in Acts 10:1–29.[7]

See also

| Books of the Torah |

|---|

|

- Torah

- The Bible and homosexuality

- Weekly Torah portions in Leviticus: Vayikra, Tzav, Shemini, Tazria, Metzora, Acharei, Kedoshim, Emor, Behar, and Bechukotai

References

- ↑ Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Megillah, p. 31B; see also Rashi on Deuteronomy, Ch. 28:23; see also the commentary of Ohr HaChaim at the beginning of Deuteronomy, where he states, "the first four books God dictated to Moses, letter by letter, and the fifth book, Moses said on his own." See also Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, Likkutei Sichot, Vol. 19, p. 9, f. 6, and see additional references there. See Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911.

- ↑ Baruch A. Levine, ""Leviticus: Its Literary History and Location in Biblical Literature, in The Book of Leviticus: Composition and Reception, ed. Rolf Rendtorff and Robert A. Kugler (Brill, 2006), pp. 11–23

- ↑ Wenham (1995): 3. "The first word of the book serves as its Hebrew title, wayyiqrā, "and he called."

- ↑ Wenham (1995): 3. "It would be wrong, however, to describe Leviticus simply as a manual for priests. It is equally, if not more, concerned with the part the laity should play in worship."

- ↑ http://chaver.com/Torah-New/English/Articles/The%20Literary%20Structure%20of%20Leviticus.htm

- ↑ Gordon Wenham, "Exploring the Old Testament: The Pentateuch" (SPCK, 2003), pp. 83–84

- ↑ Gordon Wenham, "Exploring the Old Testament: The Pentateuch" (SPCK, 2003), pp. 99–100

External links

Online translations of Leviticus:

- Jewish translations:

- Leviticus at Mechon-Mamre (Jewish Publication Society translation)

- Leviticus (The Living Torah) Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan's translation and commentary at Ort.org

- Vayikra—Levitichius (Judaica Press) translation [with Rashi's commentary] at Chabad.org

- ויקרא Vayikra—Leviticus (Hebrew—English at Mechon-Mamre.org)

- Christian translations:

- The Book of Leviticus, Douay Rheims Version, with Bishop Challoner Commentaries

- Online Bible at GospelHall.org (King James Version)

- oremus Bible Browser (New Revised Standard Version)

- oremus Bible Browser (Anglicized New Revised Standard Version)

Related article:

- Book of Leviticus article (Jewish Encyclopedia)

- The Literary Structure of Leviticus (chaver.com)

- Leviticus in Skeptic's Annotated Bible

Free Online Bibliography on Leviticus:

| Preceded by Exodus |

Hebrew Bible | Followed by Numbers |

| Christian Old Testament |