Leptin

| edit |

| Leptin | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||

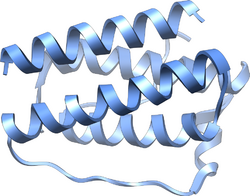

| Structure of the obese protein leptin-E100.[1] | |||||

| Identifiers | |||||

| Symbol | Leptin | ||||

| Pfam | PF02024 | ||||

| Pfam clan | CL0053 | ||||

| InterPro | IPR000065 | ||||

| SCOP | 1ax8 | ||||

|

|||||

Leptin (Greek leptos meaning thin) is a 16 kDa protein hormone that plays a key role in regulating energy intake and energy expenditure, including appetite and metabolism. It is one of the most important adipose derived hormones.[2] The Ob(Lep) gene (Ob for obese, Lep for leptin) is located on chromosome 7 in humans.[3]

Contents |

Discovery

The effects of leptin were observed by studying mutant obese mice that arose at random within a mouse colony at the Jackson Laboratory in 1950.[4] These mice were massively obese and excessively voracious. Ultimately, several strains of laboratory mice have been found to be homozygous for single-gene mutations that causes them to become grossly obese, and they fall into two classes: "ob/ob", those having mutations in the gene for the protein hormone leptin, and "db/db", those having mutations in the gene that encodes the receptor for leptin. When ob/ob mice are treated with injections of leptin they lose their excess fat and return to normal body weight.

Leptin itself was discovered in 1994 by Jeffrey M. Friedman and colleagues at the Rockefeller University through the study of such mice.[5]

Synthesis

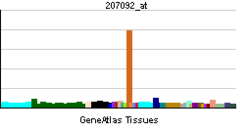

Human leptin is a protein of 167 amino acids. It is manufactured primarily in the adipocytes of white adipose tissue, and the level of circulating leptin is directly proportional to the total amount of fat in the body.

In addition to white adipose tissue—the major source of leptin—it can also be produced by brown adipose tissue, placenta (syncytiotrophoblasts), ovaries, skeletal muscle, stomach (lower part of fundic glands), mammary epithelial cells, bone marrow, pituitary and liver.[6]

Leptin has also been discovered to be synthesised from gastric chief cells and P/D1 cells in the stomach.[7]

Function

Leptin acts on receptors in the hypothalamus of the brain where it inhibits appetite by (1) counteracting the effects of neuropeptide Y (a potent feeding stimulant secreted by cells in the gut and in the hypothalamus); (2) counteracting the effects of anandamide (another potent feeding stimulant that binds to the same receptors as THC, the active ingredient of marijuana); and (3) promoting the synthesis of α-MSH, an appetite suppressant. This inhibition is long-term, in contrast to the rapid inhibition of eating by cholecystokinin (CCK) and the slower suppression of hunger between meals mediated by PYY3-36. The absence of a leptin (or its receptor) leads to uncontrolled food intake and resulting obesity. Several studies have shown that fasting or following a very-low-calorie diet (VLCD) lowers leptin levels.[8] It might be that on short-term leptin is an indicator of energy balance. This system is more sensitive to starvation than to overfeeding.[9] That is, leptin levels do not rise extensively after overfeeding. It might be that the dynamics of leptin due to an acute change in energy balance are related to appetite and eventually to food intake. Although this is a new hypothesis, there are already some data that support it.[10][11]

There is some controversy regarding the regulation of leptin by melatonin during the night. One research group suggested that increased levels of melatonin caused a downregulation of leptin.[12] However, in 2004, Brazilian researchers found that in the presence of insulin, "melatonin interacts with insulin and upregulates insulin-stimulated leptin expression", therefore causing a decrease in appetite whilst sleeping.[13]

In March 2010, researchers reported that mice with type 1 diabetes treated with leptin alone or in conjunction with insulin did better (blood sugar didn't fluctuate as much, cholesterol levels went down and they didn't form as much body fat) than mice with type 1 diabetes treated with insulin alone, raising the prospect of a new treatment for diabetes.[14]

Adiposity signal

To date, only leptin and insulin are known to act as an adiposity signal. In general,

- Leptin circulates at levels proportional to body fat.

- It enters the central nervous system (CNS) in proportion to its plasma concentration.

- Its receptors are found in brain neurons involved in regulating energy intake and expenditure.

- It controls food intake and energy expenditure by acting on receptors in the mediobasal hypothalamus[15]

Interaction with amylin

Co-administration of two neurohormones known to have a role in body weight control, amylin (produced by beta cells in the pancreas) and leptin (produced by fat cells), results in sustained, fat-specific weight loss in a leptin-resistant animal model of obesity.[16]

Satiety: appetite control

Leptin binds to neuropeptide Y (NPY) neurons in the arcuate nucleus, in such a way that decreases the activity of these neurons. Leptin signals to the brain that the body has had enough to eat, or satiety. A very small group of humans possess homozygous mutations for the leptin gene that leads to a constant desire for food, resulting in severe obesity. This condition can be treated somewhat successfully by the administration of recombinant human leptin.[17] However, extensive clinical trials using recombinant human leptin as a therapeutic agent for treating obesity in humans have been inconclusive because only the most obese subjects who were given the highest doses of exogenous leptin produced statistically significant weight loss. It was concluded that large and frequent doses were needed to only provide modest benefit because of leptin’s low circulating half-life, low potency, and poor solubility. Furthermore, these injections caused some participants to drop out of the study due to inflammatory responses of the skin at the injection site. Some of these problems can be alleviated by a form of leptin called Fc-leptin, which takes the Fc fragment from the immunoglobulin gamma chain as the N-terminal fusion partner and follows it with leptin. This Fc-leptin fusion has been experimentally proven to be highly soluble, more biologically potent, and contain a much longer serum half-life. As a result, this Fc-leptin was successfully shown to treat obesity in both leptin-deficient and normal mice, although studies have not been undertaken on human subjects. This makes Fc-leptin a potential treatment for obesity in humans after more extensive testing.[18][19][20] Thus, circulating leptin levels give the brain input regarding energy storage so it can regulate appetite and metabolism. Leptin works by inhibiting the activity of neurons that contain neuropeptide Y (NPY) and agouti-related peptide (AgRP), and by increasing the activity of neurons expressing α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH). The NPY neurons are a key element in the regulation of appetite; small doses of NPY injected into the brains of experimental animals stimulates feeding, while selective destruction of the NPY neurons in mice causes them to become anorexic. Conversely, α-MSH is an important mediator of satiety, and differences in the gene for the receptor at which α-MSH acts in the brain are linked to obesity in humans.

Circulatory system

The role of leptin/leptin receptors in modulation of T cell activity in immune system was shown in experimentation with mice. It modulates the immune response to atherosclerosis, which is a predisposing factor in patients with obesity.[21]

Leptin promotes angiogenesis by increasing vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) levels.

In some epidemiological studies, hyperleptinemia is considered as a risk factor. However, recently a handful of animal experiments demonstrated that systemic hyperleptinemia produced by infusion or adenoviral gene transfer decrease blood pressure in rats. [22] [23]

Lung surfactant activity

In fetal lung leptin is induced in the alveolar interstitial fibroblasts ("lipofibroblasts") by the action of PTHrP secreted by formative alveolar epithelium (endoderm) under moderate stretch. The leptin from the mesenchyme, in turn, acts back on the epithelium at the leptin receptor carried in the alveolar type II pneumocytes and induces surfactant expression, which is one of the main functions of these type II pneumocytes.[24]

Reproduction

In mice, leptin is also required for male and female fertility. Leptin has a lesser effect in humans. In mammals such as humans, ovulatory cycles in females are linked to energy balance (positive or negative depending on whether a female is losing or gaining weight) and energy flux (how much energy is consumed and expended) much more than energy status (fat levels). When energy balance is highly negative (meaning a woman is starving) or energy flux is very high (meaning a woman is exercising at extreme levels, but still consuming enough calories), the ovarian cycle stops and females stop menstruating. Only if a female has an extremely low body fat percentage does energy status affect menstruation. Some studies have indicated that leptin levels outside an ideal range can have a negative effect on egg quality and outcome during IVF.[25]

The body's fat cells, under normal conditions, are responsible for the constant production and release of leptin. This can also be produced by the placenta.[26] Leptin levels rise during pregnancy and fall after parturition (childbirth). Leptin is also expressed in fetal membranes and the uterine tissue. Uterine contractions are inhibited by leptin.[27]

There is also evidence that leptin plays a role in hyperemesis gravidarum (severe morning sickness),[28] in polycystic ovary syndrome[29] and a 2007 research suggests that hypothalamic leptin is implicated in bone growth.[30]

Leptin resistance and obesity

Although leptin is a circulating signal that reduces appetite, in general, obese people have an unusually high circulating concentration of leptin.[31] These people are said to be resistant to the effects of leptin, in much the same way that people with type 2 diabetes are resistant to the effects of insulin. The high sustained concentrations of leptin from the enlarged adipose stores result in leptin desensitization. The pathway of leptin control in obese people might be flawed at some point so the body doesn't adequately receive the satiety feeling subsequent to eating.

Fructose and leptin resistance

A study published recently suggests that the consumption of high amounts of fructose causes leptin resistance and elevated triglycerides in rats. The high-fructose diet rats subsequently ate more and gained more weight than controls when fed a high fat, high calorie diet.[32][33][34]

Mechanism of action

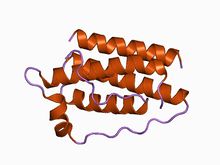

Leptin interacts with six types of receptors (Ob-Ra–Ob-Rf, or LepRa-LepRf) which in turn are encoded by a single gene, LEPR.[35] Ob-Rb is the only receptor isoform that can signal intracellularly via the Jak-Stat and MAPK signal transduction pathways,[36] and is present in hypothalamic nuclei.[37]

It is unknown whether leptin can cross the blood-brain barrier to access receptor neurons, because the blood-brain barrier is somewhat absent in the area of the median eminence, close to where the NPY neurons of the arcuate nucleus are. It is generally thought that leptin might enter the brain at the choroid plexus, where there is intense expression of a form of leptin receptor molecule that could act as a transport mechanism.

Once leptin has bound to the Ob-Rb receptor, it activates the stat3, which is phosphorylated and travels to the nucleus to, presumably, effect changes in gene expression. One of the main effects on gene expression is the down-regulation of the expression of endocannabinoids, responsible for increasing appetite. There are other intracellular pathways activated by leptin, but less is known about how they function in this system. In response to leptin, receptor neurons have been shown to remodel themselves, changing the number and types of synapses that fire onto them.

There is some recognition that leptin action is more decentralized than previously assumed. In addition to its endocrine action at a distance (from adipose tissue to brain), leptin also acts as a paracrine mediator.[6]

See also

- Teleost leptins

References

- ↑ Zhang F, Basinski MB, Beals JM, et al. (May 1997). "Crystal structure of the obese protein leptin-E100". Nature 387 (6629): 206–9. doi:10.1038/387206a0. PMID 9144295.

- ↑ Brennan AM, Mantzoros CS (June 2006). "Drug Insight: the role of leptin in human physiology and pathophysiology--emerging clinical applications". Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 2 (6): 318–27. doi:10.1038/ncpendmet0196. PMID 16932309.

- ↑ GreGreen ED, Maffei M, Braden VV, Proenca R, DeSilva U, Zhang Y, Chua SC Jr, Leibel RL, Weissenbach J, Friedman JM (August 1995). "The human obese (OB) gene: RNA expression pattern and mapping on the physical, cytogenetic, and genetic maps of chromosome 7". Genome Res. 5 (1): 5–12. doi:10.1101/gr.5.1.5. PMID 8717050.

- ↑ Ingalls AM, Dickie MM, Snell GD (December 1950). "Obese, a new mutation in the house mouse". J. Hered. 41 (12): 317–8. PMID 14824537. http://jhered.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/41/12/317.

- ↑ Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, Friedman JM (December 1994). "Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue". Nature 372 (6505): 425–32. doi:10.1038/372425a0. PMID 7984236.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Margetic S, Gazzola C, Pegg GG, Hill RA (2002). "Leptin: a review of its peripheral actions and interactions". Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 26 (11): 1407–33. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0802142. PMID 12439643.

- ↑ Bado A, Levasseur S, Attoub S, Kermorgant S, Laigneau JP, Bortoluzzi MN, Moizo L, Lehy T, Guerre-Millo M, Le Marchand-Brustel Y, Lewin MJ (August 1998). "The stomach is a source of leptin". Nature 394 (6695): 790–3. doi:10.1038/29547. PMID 9723619.

- ↑ Studies include:

- Dubuc G, Phinney S, Stern J, Havel P (1998). "Changes of serum leptin and endocrine and metabolic parameters after 7 days of energy restriction in men and women". Metab. Clin. Exp. 47 (4): 429–34. PMID 9550541.

- Pratley R, Nicolson M, Bogardus C, Ravussin E (1997). "Plasma leptin responses to fasting in Pima Indians". Am. J. Physiol. 273 (3 Pt 1): E644–9. PMID 9316457.

- Weigle D, Duell P, Connor W, Steiner R, Soules M, Kuijper J (1997). "Effect of fasting, refeeding, and dietary fat restriction on plasma leptin levels". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 82 (2): 561–5. doi:10.1210/jc.82.2.561. PMID 9024254.

- ↑ Chin-Chance C, Polonsky K, Schoeller D (2000). "Twenty-four-hour leptin levels respond to cumulative short-term energy imbalance and predict subsequent intake". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 85 (8): 2685–91. doi:10.1210/jc.85.8.2685. PMID 10946866.

- ↑ Keim N, Stern J, Havel P (1998). "Relation between circulating leptin concentrations and appetite during a prolonged, moderate energy deficit in women". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 68 (4): 794–801. PMID 9771856.

- ↑ Mars M, de Graaf C, de Groot C, van Rossum C, Kok F (2006). "Fasting leptin and appetite responses induced by a 4-day 65%-energy-restricted diet". International journal of obesity (Lond) 30 (1): 122–8. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0803070. PMID 16158086.

- ↑ Kus I, Sarsilmaz M, Colakoglu N, et al. (2004). "Pinealectomy increases and exogenous melatonin decreases leptin production in rat anterior pituitary cells: an immunohistochemical study". Physiological research / Academia Scientiarum Bohemoslovaca 53 (4): 403–8. PMID 15311999.

- ↑ Alonso-Vale MI, Andreotti S, Peres SB, Anhê GF, das Neves Borges-Silva C, Neto JC, Lima FB (April 2005). "Melatonin enhances leptin expression by rat adipocytes in the presence of insulin". Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 288 (4): E805–12. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00478.2004. PMID 15572654.

- ↑ Wang MY, Chen L, Clark GO, Lee Y, Stevens RD, Ilkayeva OR, Wenner BR, Bain JR, Charron MJ, Newgard CB, Unger RH (March 2010). "Leptin therapy in insulin-deficient type I diabetes". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 (11): 4813–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.0909422107. PMID 20194735. Lay summary – medicinenet.com.

- ↑ Williams KW, Scott MM, Elmquist JK (March 2009). "From observation to experimentation: leptin action in the mediobasal hypothalamus". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 89 (3): 985S–990S. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2008.26788D. PMID 19176744.

- ↑ Roth JD, Roland BL, Cole RL, Trevaskis JL, Weyer C, Koda JE, Anderson CM, Parkes DG, Baron AD (May 2008). "Leptin responsiveness restored by amylin agonism in diet-induced obesity: evidence from nonclinical and clinical studies". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 (20): 7257–62. doi:10.1073/pnas.0706473105. PMID 18458326.

- ↑ OMIM - LEPTIN; LEP

- ↑ Friedman JM, Halaas JL (October 1998). "Leptin and the regulation of body weight in mammals". Nature 395 (6704): 763–70. doi:10.1038/27376. PMID 9796811.

- ↑ Heymsfield SB, Greenberg AS, Fujioka K, Dixon RM, Kushner R, Hunt T, Lubina JA, Patane J, Self B, Hunt P, McCamish M (October 1999). "Recombinant leptin for weight loss in obese and lean adults: a randomized, controlled, dose-escalation trial". JAMA 282 (16): 1568–75. doi:10.1001/jama.282.16.1568. PMID 10546697.

- ↑ Lo KM, Zhang J, Sun Y, Morelli B, Lan Y, Lauder S, Brunkhorst B, Webster G, Hallakou-Bozec S, Doaré L, Gillies SD (January 2005). "Engineering a pharmacologically superior form of leptin for the treatment of obesity". Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 18 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1093/protein/gzh102. PMID 15790575.

- ↑ Taleb S, Herbin O, Ait-Oufella H, Verreth W, Gourdy P, Barateau V, Merval R, Esposito B, Clément K, Holvoet P, Tedgui A, Mallat Z. (2007). "Defective leptin/leptin receptor signaling improves regulatory T cell immune response and protects mice from atherosclerosis". Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 27 (12): 2691–8. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.149567. PMID 17690315.

- ↑ Zhang W, Telemaque S, Augustyniak R, Anderson P, Thomas G, An J, Wang Z, Newgard C, Victor R. (2010). "Adenovirus-mediated leptin expression normalises hypertension associated with diet-induced obesity". J Neuroendocrinol. 22 (3): 175–80. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2826.2010.01953.x. PMID 20059648.

- ↑ Knight W, Seth R, Boron J, Overton J. (2009). "Short-term physiological hyperleptinemia decreases arterial blood pressure". Regul Pept. 154 (1-3): 60–8. doi:10.1016/j.regpep.2009.02.001. PMID 19323984.

- ↑ John S. Torday, Virender K. Rehan (2006). "Up-regulation of fetal rat lung parathyroid hormone-related protein gene regulatory network down-regulates the Sonic Hedgehog/Wnt/betacatenin gene regulatory network". Pediatr. Res. 60 (4): 382–8. doi:10.1203/01.pdr.0000238326.42590.03. PMID 16940239. — published online before print as DOI 10.1203/01.pdr.0000238326.42590.03

- ↑ Anifandis G, Koutselini E, Louridas K, Liakopoulos V, Leivaditis K, Mantzavinos T, Sioutopoulou D, Vamvakopoulos N (April 2005). "Estradiol and leptin as conditional prognostic IVF markers". Reproduction 129 (4): 531–4. doi:10.1530/rep.1.00567. PMID 15798029.

- ↑ Zhao J, Townsend KL, Schulz LC, Kunz TH, Li C, Widmaier EP (2004). "Leptin receptor expression increases in placenta, but not hypothalamus, during gestation in Mus musculus and Myotis lucifugus". Placenta 25 (8-9): 712–22. doi:10.1016/j.placenta.2004.01.017. PMID 15450389.

- ↑ Moynihan AT, Hehir MP, Glavey SV, Smith TJ, Morrison JJ (2006). "Inhibitory effect of leptin on human uterine contractility in vitro". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 195 (2): 504–9. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2006.01.106. PMID 16647683.

- ↑ Aka N, Atalay S, Sayharman S, Kiliç D, Köse G, Küçüközkan T (2006). "Leptin and leptin receptor levels in pregnant women with hyperemesis gravidarum". The Australian & New Zealand journal of obstetrics & gynaecology 46 (4): 274–7. doi:10.1111/j.1479-828X.2006.00590.x. PMID 16866785.

- ↑ Cervero A, Domínguez F, Horcajadas JA, Quiñonero A, Pellicer A, Simón C (2006). "The role of the leptin in reproduction". Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 18 (3): 297–303. doi:10.1097/01.gco.0000193004.35287.89. PMID 16735830.

- ↑ Iwaniec UT, Boghossian S, Lapke PD, Turner RT, Kalra SP (2007). "Central leptin gene therapy corrects skeletal abnormalities in leptin-deficient ob/ob mice". Peptides 28 (5): 1012. doi:10.1016/j.peptides.2007.02.001. PMID 17346852.

- ↑ Considine RV, Sinha MK, Heiman ML, Kriauciunas A, Stephens TW, Nyce MR, Ohannesian JP, Marco CC, McKee LJ & Bauer TL (1996). "Serum Immunoreactive-Leptin Concentrations in Normal-Weight and Obese Humans". N Engl J Med 334 (5): 292–295. doi:10.1056/NEJM199602013340503. PMID 8532024.

- ↑ "Fructose Sets Table For Weight Gain Without Warning". Science News. Science Daily. 2008-10-19. http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/10/081016074701.htm. Retrieved 2008-11-15.

- ↑ Vasselli JR (November 2008). "Fructose-induced leptin resistance: discovery of an unsuspected form of the phenomenon and its significance. Focus on "Fructose-induced leptin resistance exacerbates weight gain in response to subsequent high-fat feeding," by Shapiro et al.". Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 295 (5): R1365–9. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.90674.2008. PMID 18784330.

- ↑ Shapiro A, Mu W, Roncal C, Cheng KY, Johnson RJ, Scarpace PJ (November 2008). "Fructose-induced leptin resistance exacerbates weight gain in response to subsequent high-fat feeding". Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 295 (5): R1370–5. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00195.2008. PMID 18703413.

- ↑ Wang MY, Zhou YT, Newgard CB, Unger RH (August 1996). "A novel leptin receptor isoform in rat". FEBS Lett. 392 (2): 87–90. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(96)00790-9. PMID 8772180.

- ↑ Malendowicz W, Rucinski M, Macchi C, Spinazzi R, Ziolkowska A, Nussdorfer GG, Kwias Z (October 2006). "Leptin and leptin receptors in the prostate and seminal vesicles of the adult rat". Int. J. Mol. Med. 18 (4): 615–8. PMID 16964413. http://www.spandidos-publications.com/ijmm/article.jsp?article_id=ijmm_18_4_615.

- ↑ "LepRb antibody (commercial site)". http://www.neuromics.com/ittrium/visit?path=A1x66x1y1x9fx1y1x246x1y1x372x1x82y1x35d4x1x7f.

Further reading

- Torday JS, Sun H, Wang L, Torres E, Sunday ME, Rubin LP (March 2002). "Leptin mediates the parathyroid hormone-related protein paracrine stimulation of fetal lung maturation". Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 282 (3): L405–10. PMID 11839533.

- Torday JS, Rehan VK (July 2002). "Stretch-stimulated surfactant synthesis is coordinated by the paracrine actions of PTHrP and leptin". Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 283 (1): L130–5. doi:10.1152/ajplung.00380.2001 (inactive 2010-08-06). PMID 12060569.

- Dubey L, Hesong Z (2006). "Role of leptin in atherogenesis". Exp Clin Cardiol 11 (4): 269–75. PMID 18651016.

- Friedman JM, Halaas JL (1998). "Leptin and the regulation of body weight in mammals.". Nature 395 (6704): 763–70. doi:10.1038/27376. PMID 9796811.

- Prolo P, Wong ML, Licinio J (1999). "Leptin.". Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 30 (12): 1285–90. doi:10.1016/S1357-2725(98)00094-6. PMID 9924798.

- Heshka JT, Jones PJ (2001). "A role for dietary fat in leptin receptor, OB-Rb, function.". Life Sci. 69 (9): 987–1003. doi:10.1016/S0024-3205(01)01201-2. PMID 11508653.

- Janeckova R (2002). "The role of leptin in human physiology and pathophysiology.". Physiological research / Academia Scientiarum Bohemoslovaca 50 (5): 443–59. PMID 11702849.

- Lee DW, Leinung MC, Rozhavskaya-Arena M, Grasso P (2002). "Leptin and the treatment of obesity: its current status.". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 440 (2-3): 129–39. doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(02)01424-3. PMID 12007531.

- Al-Daghri N, Bartlett WA, Jones AF, Kumar S (2002). "Role of leptin in glucose metabolism in type 2 diabetes.". Diabetes, obesity & metabolism 4 (3): 147–55. doi:10.1046/j.1463-1326.2002.00194.x. PMID 12047393.

- Sabath Silva EF (2002). "[Leptin]". Rev. Invest. Clin. 54 (2): 161–5. PMID 12053815.

- Thomas T, Burguera B (2003). "Is leptin the link between fat and bone mass?". J. Bone Miner. Res. 17 (9): 1563–9. doi:10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.9.1563. PMID 12211425.

- Kraemer RR, Chu H, Castracane VD (2002). "Leptin and exercise.". Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 227 (9): 701–8. PMID 12324651.

- Waelput W, Brouckaert P, Broekaert D, Tavernier J (2003). "A role for leptin in the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and in immune response.". Current drug targets. Inflammation and allergy 1 (3): 277–89. doi:10.2174/1568010023344634. PMID 14561193.

- Stenvinkel P, Pecoits-Filho R, Lindholm B (2004). "Leptin, ghrelin, and proinflammatory cytokines: compounds with nutritional impact in chronic kidney disease?". Advances in renal replacement therapy 10 (4): 332–45. doi:10.1053/j.arrt.2003.08.009. PMID 14681862.

- Cohen P, Ntambi JM, Friedman JM (2004). "Stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 and the metabolic syndrome.". Curr. Drug Targets Immune Endocr. Metabol. Disord. 3 (4): 271–80. doi:10.2174/1568008033340117. PMID 14683458.

- Sahu A (2004). "Leptin signaling in the hypothalamus: emphasis on energy homeostasis and leptin resistance.". Frontiers in neuroendocrinology 24 (4): 225–53. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2003.10.001. PMID 14726256.

- Elefteriou F, Karsenty G (2004). "[Bone mass regulation by leptin: a hypothalamic control of bone formation]". Pathol. Biol. 52 (3): 148–53. doi:10.1016/j.patbio.2003.05.006. PMID 15063934.

- Blüher S, Mantzoros CS (2004). "The role of leptin in regulating neuroendocrine function in humans.". J. Nutr. 134 (9): 2469S–2474S. PMID 15333744.

- Farooqi S, O'Rahilly S (2007). "Genetics of obesity in humans.". Endocr. Rev. 27 (7): 710–18. doi:10.1210/er.2006-0040. PMID 17122358.

External links

- Leptin in a bulletin by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI)

- Leptin: Your brain, appetite and obesity by the British Society of Neuroendocrinology

- Leptin/ghrelin and their role in obesity from hungerhormones.com, a weight control website

- Leptin by Colorado State University

- Leptin at 3Dchem.com, description and structure diagrams

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||