Lance

Lance is a catchall term for a variety of different pole weapons based on the spear. The name is derived from lancea, Roman auxiliaries' javelin, although according to the OED, the word may be of Iberian origin.

A lance in the original sense is a light throwing spear, or javelin. The English verb to launch "fling, hurl, throw" is derived from the term (via Old French lancier), as well as the rarer or poetic to lance. The term from the 17th century came to refer specifically to spears not thrown, used for thrusting by heavy cavalry, and especially in jousting. A thrusting spear which is used by infantry is usually referred to as a pike.

The Roman cavalry long thrusting spear was not called lance, but contus (from Greek language kontos, barge-pole). It was usually 3 to 4 m long, and grasped with both hands. It was used by equites contariorum and equites catafractarii, fully armed and armoured cataphracts. Romans weren't the first, though; the first use of the lance in this sense was made by the Sarmatian and Parthian cataphracts from ca. the 3rd century BC, and cavalry long thrusting spear was especially popular among the Hellenistic armies' agema and line cavalry.

The use of the basic cavalry spear is so ancient, and warfare so ubiquitous by the beginning of recorded history, that it is difficult to determine which populations invented the lance and which learned it from their enemies or allies.

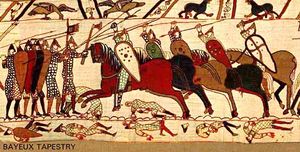

The best known usage of military lances was that of the full-gallop closed-ranks and usually wedge-shaped charge of a group of knights with underarm-couched lances, against lines of infantry, archery regiments, defensive embankments, and opposition cavalry. It is commonly believed that this became the dominant European cavalry tactic in the 11th century after the development of the cantled saddle and stirrups (the Great Stirrup Controversy), and of rowel spurs (which enabled better control of the mount). Cavalry thus outfitted and deployed had a tremendous collective force in their charge, and could shatter most contemporary infantry lines. Recent evidence has suggested, however, that the lance charge was effective without the benefit of stirrups.[1]

One of the most effective pre-stirrup lanced cavalry units was Alexander the Great's Companion cavalry, who were successful against both heavy infantry and cavalry units.

The Byzantine cavalry used lance (kontos or kontarion) almost exclusively, often in mixed lancer and mounted archer formations (cursores et defensores). The Byzantines used lance both overarm and underarm, couched.

While it could still be generally classified as a spear, the lance tends to be larger - usually both longer and stouter and thus also considerably heavier, and unsuited for throwing, or for the rapid thrusting, as with an infantry spear. Lances did not have spear tips that (intentionally) broke off or bent, unlike many throwing weapons of the spear/javelin family, and were adapted for mounted combat. They were often equipped with a vamplate, a small circular plate to prevent the hand sliding up the shaft upon impact. Though perhaps most known as one of the foremost military and sporting weapons used by European knights, the use of lances was spread throughout the Old World wherever mounts were available. As a secondary weapon, lancers of the period also bore swords, maces or something else suited to close quarter battle, since the lance was often a one-use-per-engagement weapon; after the initial charge, the weapon was far too long, heavy and slow to be effectively used against opponents in a melee.

Because of the extreme stopping power of a thrusting spear, it quickly became a popular weapon of footmen in the Late Middle Ages. These eventually led to the rise of the longest type of spears ever, the pike. Ironically, this adaptation of the cavalry lance to infantry use was largely tasked with stopping lance-armed cavalry charges. During the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries, these weapons, both mounted and unmounted, were so effective that lancers and pike men not only became a staple of every Western army, but also became highly sought-after mercenaries.

In Europe, a jousting lance was a variation of the knight's lance which was modified from its original war design. In jousting, the lance tips would usually be blunt, often spread out like a cup or furniture foot, to provide a wider impact surface designed to unseat the opposing rider without spearing him through. The center of the shaft of such lances could be designed to be hollow, in order for it to break on impact, as a further safeguard against impalement. They were often 4 m long or longer, and had special hand guards built into the lance, often tapering for a considerable portion of the weapon's length. These are the versions that can most often be seen at medieval reenactment festivals. In war, lances were much more like stout spears, long and balanced for one handed use, and with decidedly sharp tips.

The mounted lance saw a renaissance in the 18th century with the demise of the pike; heavily armoured cuirassiers used 2 to 3 m lances as their main weapons. They were usually used for the breakneck charge against the enemy infantry.

The Crimean War saw the most infamous though ultimately unsuccessful use of the lance, the Charge of the Light Brigade.

After the Western introduction of the horse to Native Americans, the Plains Indians also took up the lance, probably independently, as American cavalry of the time were sabre- and pistol-armed, firing forward at full gallop. The natural adaptation of the throwing spear to a stouter thrusting and charging spear appears to be an inevitable evolutionary trend in the military use of the horse, and a rapid one at that.

American cavalry and Canadian North-West Mounted Police used a fine lance as a flagstaff. In 1886, the first official musical ride was performed in Regina, with this fine ceremonial lance playing a significant role in the choreography. The world's oldest continuous Mounted Police unit in the world, being the New South Wales Mounted Police, housed at Redfern Barracks, Sydney, Australia, carries a lance with a navy blue and white pennant in all ceremonial occasions.

During the Second Boer War, British troops successfully used the lance against the Boers in the first few battles, but the Boers adopted the use of trench warfare, machine guns and long range rifles. The combined effect was devastating, so that British cavalry were remodeled as high mobility infantry units ('dragoons') fighting on foot. It was not until the development of the tank in World War I that mounted attacks were once again possible, but its mechanical technology doomed both the horse cavalry and the lance.

"Lance" is also the name given by some anthropologists to the light flexible javelins (technically, darts) thrown by atlatls (spear-throwing sticks), but these are usually called "atlatl javelins". Some were not much larger than arrows, and were typically feather-fletched like an arrow, and unlike the vast majority of spears and javelins (one exception would be several instances of the many types of ballista bolt, a mechanically-thrown spear).

Lance (unit organization): The small unit that surrounded a knight when he went into battle during the 14th and 15th centuries. A lance might have consisted of one or two squires, the knight himself, one to three men-at-arms, and possibly an archer. Lances were often combined under the banner of a higher ranking nobleman to form companies of knights that would act as an ad-hoc unit.

See also

- Heavy cavalry

- Lances fournies

- Lancer

- Jousting

- Tent pegging

- Hastilude

- Buttero

References

- Delbrück, Hans. History of the Art of War, originally published in 1920; University of Nebraska Press (reprint), 1990 (trans. J. Renfroe Walter). Volume III: Medieval Warfare.

External links

- From Lance to Pistol: The Evolution of Mounted Soldiers from 1550 to 1600 (myArmoury.com article)