Hadrosaurid

| Hadrosaurids Fossil range: Late Cretaceous, 100–65.5 Ma |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Parasaurolophus cyrtocristatus at Field Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Superorder: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | Ornithischia |

| Suborder: | Cerapoda |

| Infraorder: | Ornithopoda |

| Superfamily: | Hadrosauroidea |

| Family: | Hadrosauridae Cope, 1869 |

| Subfamilies | |

|

|

| Synonyms | |

|

|

Hadrosaurids or duck-billed dinosaurs are members of the family Hadrosauridae, and include ornithopods such as Edmontosaurus and Parasaurolophus. They were common herbivores in the Upper Cretaceous Period of what are now Asia, Europe and North America. They are descendants of the Upper Jurassic/Lower Cretaceous iguanodontian dinosaurs and had similar body layout. They were ornithischians.

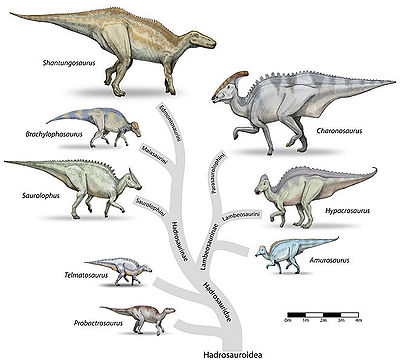

Hadrosaurids are divided into two subfamilies. The lambeosaurines (Lambeosaurinae) had hollow cranial crests or tubes, and were generally less bulky. The saurolophines (Saurolophinae) lacked hollow cranial crests (solid crests were present in some forms) and were generally larger.

Contents |

Characteristics

The hadrosaurs are known as the duck-billed dinosaurs due to the similarity of their head to that of modern ducks. In some genera, most notably Anatotitan, the whole front of the skull was flat and broadened out to form a beak, ideal for clipping leaves and twigs from the forests of Asia, Europe and North America. However, the back of the mouth contained literally thousands of teeth suitable for grinding food before it was swallowed. This has been hypothesized to have been a crucial factor in the success of this group in the Cretaceous, compared to the sauropods which were still largely dependent on gastroliths for grinding their food.

In 2009, paleontologist Mark Purnell conducted a study into the chewing methods and diet of hadrosaurids, a herbivore species of duck-billed dinosaurs from the Late Cretaceous period. By analyzing hundreds of microscopic scratches on the teeth of a fossilized Edmontosaurus jaw, the team determined hadrosaurs had a unique way of eating unlike any creature living today. In contrast to a flexible lower jaw joint prevalent in today's mammals, hadrosaurs had a unique hinge between the upper jaws and the rest of its skull. The team found the dinosaur's upper jaws pushed outwards and sideways while chewing, as the lower jaw slid against the upper teeth.[1]

Discoveries

Hadrosaurids were the first dinosaur family to be identified in North America, the first traces being found in 1855-1856 with the discovery of fossil teeth. Joseph Leidy examined the teeth, and erected the genera Trachodon and Thespesius (others included Troodon, Deinodon and Palaeoscincus). One species was named Trachodon mirabilis. Now it seems that the teeth genus Trachodon is a mixture of all sorts of cerapod dinosaurs, including ceratopsids. In 1858 the teeth were associated with Leidy's eponymous Hadrosaurus foulkii, named after the fossil hobbyist William Parker Foulke. More and more teeth were found, resulting in even more (now obsolete) genera.

A second duck-bill skeleton was unearthed, and was named Diclonius mirabilis in 1883 by Edward Drinker Cope, which he incorrectly used in favor of Trachodon mirabilis. But Trachodon, together with other poorly typed genera, was used more widely and, when Cope's famous "Diclonius mirabilis" skeleton was mounted at the American Museum of Natural History, it was labeled as "Trachodont dinosaur". The duck-billed dinosaur family was then named Trachodontidae.

A very well-preserved complete hadrosaurid specimen (Edmontosaurus annectens) was recovered in 1908 by the fossil collector Charles Hazelius Sternberg and his three sons, in Converse County, Wyoming. Analyzed by Henry Osborn in 1912, it has come to be known as the "Trachodon mummy". This specimen's skin was almost completely preserved in the form of impressions.

Lawrence Lambe erected the genus Edmontosaurus ("lizard from Edmonton") in 1917 from a find in the lower Edmonton Formation (now Horseshoe Canyon Formation), Alberta. Hadrosaurid systematics were addressed in a 1942 monograph by Richard Swann Lull and Nelda Wright. They proposed the genus Anatosaurus for several species of dubious genera. Cope's famous mount at the AMNH became Anatosaurus copei. In 1990, Anatosaurus was moved to Edmontosaurus. One former Anatosaurus species was distinct enough from Edmontosaurus to be placed in a separate genus, named Anatotitan, so in 1990 the AMNH mount was re-labelled Anatotitan copei.

Paleontologists have found a hadrosaurid leg bone in Paleocene rocks, but it was probably reworked from a Cretaceous source.[2]

One of the most complete fossilized specimens was found in 1999 in Hell Creek Formation of North Dakota and now is nicknamed "Dakota". The hadrosaur fossil is so well preserved that scientists have been able to calculate its muscle mass and learn that it was more muscular than thought, probably giving it the ability to outrun predators such as Tyrannosaurus rex. Unlike the collections of bones found in museums, this mummified hadrosaur fossil comes complete with skin (not merely skin impressions), ligaments, tendons and possibly some internal organs. It is being analyzed in the world's largest CT scanner, operated by the Boeing Co.[3] The machine usually is used for detecting flaws in space shuttle engines and other large objects, but previously none as large as this. Researchers hope the technology will help them learn more about the fossilized insides of the creature. They also found a gap of about a centimeter between each vertebra, indicating there may have been a disk or other material between them, allowing more flexibility and meaning the animal was actually longer than what is shown in a museum.[4]

Classification

The family Hadrosauridae was first used by Edward Drinker Cope in 1869. Since its creation, a major division has been recognized in the group, between the (generally crested) subfamily Lambeosaurinae and (generally crestless) subfamily Saurolophinae (or Hadrosaurinae). Phylogenetic analysis has increased the resolution of hadrosaurid relationships considerably (see Phylogeny below), leading to the widespread usage of tribes (a taxonomic unit below subfamily) to describe the finer relationships within each group of hadrosaurids. However, many hadrosaurid tribes commonly recognized in online sources have not yet been formally defined or seen wide use in the literature. Several were briefly mentioned but not named as such in the first edition of The Dinosauria, under informal names. In this 1990 reference, "gryposaurs" included Aralosaurus, Gryposaurus, Hadrosaurus, and Kritosaurus; "brachylophosaurs" included Brachylophosaurus and Maiasaura; "saurolophs" included Lophorhothon, Prosaurolophus, and Saurolophus; and "edmontosaurs" included Anatotitan, Edmontosaurus, and Shantungosaurus.[5]

Lambeosaurines have also been split into Parasaurolophini (Parasaurolophus) and Corythosaurini (Corythosaurus, Hypacrosaurus, and Lambeosaurus).[6] Corythosaurini and Parasaurolophini as terms entered the formal literature in Evans and Reisz's 2007 redescription of Lambeosaurus magnicristatus. Corythosaurini is defined as all taxa more closely related Corythosaurus casuarius than to Parasaurolophus walkeri, and Parasaurolophini as all those taxa closer to P. walkeri than to C. casuarius. In this study, Charonosaurus and Parasaurolophus are parasaurolophins, and Corythosaurus, Hypacrosaurus, Lambeosaurus, Nipponosaurus, and Olorotitan are corythosaurins.[7] The enigmatic genus Tsintaosaurus may form a clade in Lambeosaurine with Pararhabdodon and its probable synonym Koutalisaurus.[8]

The use of the term Hadrosaurinae was questioned in a comprehensive study of hadrosaurid relationships by Albert Prieto-Márquez in 2010. Prieto-Márquez noted that, though the name Hadrosaurinae had been used for the clade of mostly crestless hadrosaurids by nearly all previous studies, its type species, Hadrosaurus foulkii, has almost always been excluded from the clade that bears its name, in violation of the rules for naming animals set out by the ICZN. Prieto-Márquez defined Hadrosaurinae as only the lineage containing H. foulkii, and used the name Saurolophinae instead for the traditional grouping.[9]

Taxonomy

The following taxonomy includes dinosaurs currently referred to the Hadrosauridae and its subfamilies. Hadrosaurids that were accepted as valid but were not placed in a cladogram at the time of Prieto-Márquez's 2010 study[9] are included at the highest level to which they were placed (either then, or in their description if they postdate the papers used here).

- Family Hadrosauridae

- Claosaurus

- Lophorhothon

- Telmatosaurus

- Subfamily Hadrosaurinae

- Hadrosaurus

- Subfamily Saurolophinae

- Barsboldia

- Brachylophosaurus

- Edmontosaurus (including Anatotitan in Horner et al., 2004[10])

- Gryposaurus

- Kerberosaurus

- Kritosaurus

- "Kritosaurus" australis

- Lophorhothon

- Maiasaura

- Naashoibitosaurus

- Prosaurolophus

- Saurolophus

- Secernosaurus

- Shantungosaurus

- Wulagasaurus

- Hadrosaurinae incertae sedis

- Anasazisaurus

- Subfamily Lambeosaurinae

- Amurosaurus

- Angulomastacator[11]

- Aralosaurus

- Arenysaurus[12]

- Charonosaurus

- Corythosaurus

- Hypacrosaurus

- Jaxartosaurus

- Lambeosaurus

- Nipponosaurus

- Olorotitan

- Pararhabdodon

- Parasaurolophus

- Sahaliyania

- Tsintaosaurus

- Velafrons

- Lambeosaurinae incertae sedis

- Nanningosaurus

- Hadrosaurids of uncertain placement (incertae sedis)

- Gilmoreosaurus

- Koutalisaurus

- Zhuchengosaurus

- Dubious hadrosaurids

- Arstanosaurus

- Cionodon

- Diclonius

- Dysganus

- Hypsibema

- Mandschurosaurus

- Microhadrosaurus

- Orthomerus

- Pteropelyx

- Thespesius

- Trachodon

Phylogeny

Hadrosauridae was first defined as a clade, by Forster in a 1997 abstract, as simply "Lambeosaurinae plus Hadrosaurinae and their most recent common ancestor." In 1998, Paul Sereno defined the clade Hadrosauridae as the most inclusive possible group containing Saurolophus (a well-known hadrosaurine) and Parasaurolophus (a well-known lambeosaurine), later emending the definition to include Hadrosaurus, the type genus of the family, which ICZN rules state must be included, despite its status as a nomen dubium. According to Horner et al. (2004), Sereno's definition would place a few other well-known hadrosaurs (such as Telmatosaurus and Bactrosaurus) outside the family, which led them to define the family to include Telmatosaurus by default.

The following cladogram follows a 2010 phylogenetic analysis by , in the second edition of The Dinosauria.

| Hadrosauridae |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hadrosaurine cladogram

Hadrosauridae has not been subjected to as many phylogenetic analyses as other dinosaur groups, so other workers may find quite different phylogenies. Gates and Sampson (2007) published the following alternate cladogram of Hadrosaurinae in their description of Gryposaurus monumentensis:[13]

| unnamed |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lambeosaurine cladogram

The following cladogram is after the 2007 redescription of Lambeosaurus magnicristatus (Evans and Reisz, 2007):[7]

| Hadrosauridae |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lifestyle

Diet

While studying into the chewing methods of hadrosaurids in 2009, the paleontologists Vincent Williams, Paul Barrett, and Mark Purnell also found that hadrosaurs likely grazed on horsetails and vegetation close to the ground, rather than browsing higher-growing leaves and twigs. This conclusion was based upon the evenness of scratches on hadrosaur teeth, which suggested the hadrosaur used the same series of jaw motions over and over again.[14] As a result, the study determined that the hadrosaur diet was probably made of leaves and lacked the bulkier items such as twigs or stems, which might have required a different chewing method and created different wear patterns.[15] However, Purnell said these conclusions were less secure than the more conclusive evidence regarding the motion of teeth while chewing.[1]

The hypothesis that hadrosaurs were likely grazers rather than browsers appears to contradict previous findings from preserved stomach contents found in the fossilized guts in previous hadrosaurs studies.[1] The most recent such finding before the publication of the Purnell study was conducted in 2008, when a team led by University of Colorado at Boulder graduate student Justin S. Tweet found a homogeneous accumulation of millimeter-scale leaf fragments in the gut region of a well-preserved partially-grown Brachylophosaurus.[16][17] As a result of that finding, Tweet concluded in September 2008 that the animal was likely a browser, not a grazer.[17] In response to such findings, Purnell said preserved stomach contents are questionable because they do not necessarily represent the usual diet of the animal. The issue remains a subject of debate.[18]

Coprolites (fossilized droppings) of some Late Cretaceous hadrosaurs show that the animals sometimes deliberately ate rotting wood. Wood itself is not nutritious, but decomposing wood would have contained fungi, decomposed wood material and detritus-eating invertebrates, all of which would have been nutritious.[19]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Boyle, Alan (2009-06-29). "How dinosaurs chewed". MSNBC. http://cosmiclog.msnbc.msn.com/archive/2009/06/29/1981788.aspx. Retrieved 2009-06-03.

- ↑ Fassett, J, Zielinski, R.A., and Budahn, J.R. (2002). Dinosaurs that did not die; evidence for Paleocene dinosaurs in the Ojo Alamo Sandstone, San Juan Basin, New Mexico. In: Koeberl, C., and MacLeod, K. (eds.). Catastrophic events and mass extinctions: impacts and beyond. Special Paper - Geological Society of America 356:307-336.

- ↑ (Reuters News) "Mummified dinosaur reveals surprises: scientists" 3 December 2007.

- ↑ SCHMID, RANDOLPH (December 3, 5:52 PM EST). "'Mummified Dinosaur May Have Outrun T Rex". Associated Press. http://hosted.ap.org/dynamic/stories/D/DINOSAUR_MUMMY?SITE=WIMAR&SECTION=HOME&TEMPLATE=DEFAULT. Retrieved 2007-12-03.

- ↑ Weishampel, David B.; and Horner, Jack R. (1990). "Hadrosauridae". In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (1st ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 534–561. ISBN 0-520-06727-4.

- ↑ Glut, Donald F. (1997). Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. p. 69. ISBN 0-89950-917-7.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Evans, David C.; and Reisz, Robert R. (2007). "Anatomy and relationships of Lambeosaurus magnicristatus, a crested hadrosaurid dinosaur (Ornithischia) from the Dinosaur Park Formation, Alberta". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 27 (2): 373–393. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[373:AAROLM]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Prieto-Márquez, A.; and Wagner, J.R. (2009). "Pararhabdodon isonensis and Tsintaosaurus spinorhinus: a new clade of lambeosaurine hadrosaurids from Eurasia". Cretaceous Research online preprint. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2009.06.005.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Prieto-Márquez, A. (2010). "Global phylogeny of hadrosauridae (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda) using parsimony and Bayesian methods." Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 159: 435–502.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedHWF04 - ↑ Wagner, Jonathan R.; Lehman, Thomas M. (2009). "An Enigmatic New Lambeosaurine Hadrosaur (Reptilia: Dinosauria) from the Upper Shale Member of the Campanian Aguja Formation of Trans-Pecos Texas". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29 (2): 605–611. doi:10.1671/039.029.0208. http://www.bioone.org/doi/abs/10.1671/039.029.0208.

- ↑ Pereda-Suberbiola, Xabier; José Ignacio Canudo; Penélope Cruzado-Caballero; José Luis Barco; Nieves López-Martínez; Oriol Oms; and José Ignacio Ruiz-Omeñaca (2009). "The last hadrosaurid dinosaurs of Europe: A new lambeosaurine from the Uppermost Cretaceous of Aren (Huesca, Spain)". Comptes Rendus Palevol online preprint. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2009.05.002.

- ↑ Gates, Terry A.; Sampson, Scott D. (2007). "A new species of Gryposaurus (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae) from the late Campanian Kaiparowits Formation, southern Utah, USA". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 151 (2): 351–376. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2007.00349.x.

- ↑ Williams, Vincent S.; Barrett, Paul M.; and Purnell, Mark A. (2009). "Quantitative analysis of dental microwear in hadrosaurid dinosaurs,and the implications for hypotheses of jaw mechanics and feeding". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106 (27): 11194–11199. doi:10.1073/pnas.0812631106.

- ↑ Bryner, Jeanna (2009-06-29). "Study hints at what and how dinosaurs ate". LiveScience. http://www.livescience.com/animals/090629-dino-teeth.html. Retrieved 2009-06-03.

- ↑ Tweet, Justin S.; Chin, Karen; Braman, Dennis R.; and Murphy, Nate L. (2008). "Probable gut contents within a specimen of Brachylophosaurus canadensis (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous Judith River Formation of Montana". PALAIOS 23 (9): 624–635. doi:10.2110/palo.2007.p07-044r.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Lloyd, Robin (2008-09-25). "Plant-eating dinosaur spills his guts: Fossil suggests hadrosaur's last meal included lots of well-chewed leaves". MSNBC. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/26893497/ns/technology_and_science-science/. Retrieved 2009-06-03.

- ↑ This information comes from the aforementioned Alan Boyle source from June 29, 2009. However, this specific information is not included in the body of the article, but rather a response by Boyle to comments in the article. Since the comments were written by Boyle himself, and since they cite information he received specifically from Purnell, they are as legitimate a source of information as the article itself.

- ↑ Chin, K. (September 2007). "The Paleobiological Implications of Herbivorous Dinosaur Coprolites from the Upper Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation of Montana: Why Eat Wood?". Palaios 22 (5): 554. doi:10.2110/palo.2006.p06-087r. http://www.bioone.org/perlserv/?request=get-document&doi=10.2110%2Fpalo.2006.p06-087r. Retrieved 2008-09-10.