Arginine

| L-Arginine | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

(S)-2-Amino-5-guanidinopentanoic acid

|

|

|

Other names

Arginine

|

|

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 74-79-3 |

| PubChem | 6322 |

| ChemSpider | 227 |

| IUPHAR ligand | 721 |

|

SMILES

O=C(O)C(N)CCC/N=C(\N)N

|

|

|

InChI

InChI=1/C6H14N4O2/c7-4(5(11)12)2-1-3-10-6(8)9/h4H,1-3,7H2,(H,11,12)(H4,8,9,10)

Key: ODKSFYDXXFIFQN-UHFFFAOYAT |

|

| Properties | |

| Molecular formula | C6H14N4O2 |

| Molar mass | 174.2 g mol−1 |

| Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C, 100 kPa) |

|

| Infobox references | |

Arginine (abbreviated as Arg or R)[1] is an α-amino acid. The L-form is one of the 20 most common natural amino acids. At level of molecular genetics, in the structure of the messenger ribonucleic acid mRNA, CGU, CGC, CGA, CGG, AGA, and AGG, are the triplets of nucleotide bases or codons that codify for arginine during protein synthesis. In mammals, arginine is classified as a semiessential or conditionally essential amino acid, depending on the developmental stage and health status of the individual.[2] Infants are unable to meet their requirements and thus arginine is nutritionally essential for infants.[3] Arginine was first isolated from a lupin seedling extract in 1886 by the Swiss chemist Ernst Schultze.

Contents |

Structure

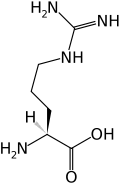

The amino acid side chain of arginine consists of a 3-carbon aliphatic straight chain, the distal end of which is capped by a complex guanidinium group.

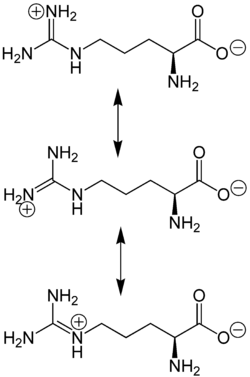

With a pKa of 12.48, the guanidinium group is positively charged in neutral, acidic and even most basic environments, and thus imparts basic chemical properties to arginine. Because of the conjugation between the double bond and the nitrogen lone pairs, the positive charge is delocalized, enabling the formation of multiple H-bonds.

Sources

Dietary sources

Arginine is a conditionally nonessential amino acid, meaning most of the time it can be manufactured by the human body, and does not need to be obtained directly through the diet. The biosynthetic pathway however does not produce sufficient arginine, and some must still be consumed through diet. Individuals who have poor nutrition or certain physical conditions may be advised to increase their intake of foods containing arginine. Arginine is found in a wide variety of foods, including[4]:

- Animal sources: dairy products (e.g. cottage cheese, ricotta, milk, yogurt, whey protein drinks), beef, pork (e.g. bacon, ham), gelatin , poultry (e.g. chicken and turkey light meat), wild game (e.g. pheasant, quail), seafood (e.g. halibut, lobster, salmon, shrimp, snails, tuna)

- Vegetable sources: wheat germ and flour, buckwheat, granola, oatmeal, peanuts, nuts (coconut, pecans, cashews, walnuts, almonds, Brazil nuts, hazelnuts, pinenuts), seeds (pumpkin, sesame, sunflower), chick peas, cooked soybeans, phalaris canariensis (canaryseed or ALPISTE)

Biosynthesis

Arginine is synthesized from citrulline by the sequential action of the cytosolic enzymes argininosuccinate synthetase (ASS) and argininosuccinate lyase (ASL). This is energetically costly, as the synthesis of each molecule of argininosuccinate requires hydrolysis of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to adenosine monophosphate (AMP); i.e., two ATP equivalents.

Citrulline can be derived from multiple sources:

- from arginine via nitric oxide synthase (NOS)

- from ornithine via catabolism of proline or glutamine/glutamate

- from asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) via DDAH

The pathways linking arginine, glutamine, and proline are bidirectional. Thus, the net utilization or production of these amino acids is highly dependent on cell type and developmental stage.

On a whole-body basis, synthesis of arginine occurs principally via the intestinal–renal axis, wherein epithelial cells of the small intestine, which produce citrulline primarily from glutamine and glutamate, collaborate with the proximal tubule cells of the kidney, which extract citrulline from the circulation and convert it to arginine, which is returned to the circulation. Consequently, impairment of small bowel or renal function can reduce endogenous arginine synthesis, thereby increasing the dietary requirement.

Synthesis of arginine from citrulline also occurs at a low level in many other cells, and cellular capacity for arginine synthesis can be markedly increased under circumstances that also induce iNOS. Thus, citrulline, a coproduct of the NOS-catalyzed reaction, can be recycled to arginine in a pathway known as the citrulline-NO or arginine-citrulline pathway. This is demonstrated by the fact that in many cell types, citrulline can substitute for arginine to some degree in supporting NO synthesis. However, recycling is not quantitative because citrulline accumulates along with nitrate and nitrite, the stable end-products of NO, in NO-producing cells.[5]

Function

Arginine plays an important role in cell division, the healing of wounds, removing ammonia from the body, immune function, and the release of hormones.[2][6][7] Arginine taken in combination with proanthocyanidins[8] or yohimbine[9], has also been used as a treatment for erectile dysfunction.

The benefits and functions attributed to oral supplementation of L-arginine include:

- Precursor for the synthesis of nitric oxide (NO)[10]

- Reduces healing time of injuries (particularly bone)[6][7]

- Quickens repair time of damaged tissue[6][7]

- Helps decrease blood pressure[11][12]

In proteins

The distributing basics of the moderate structure found in geometry, charge distribution and ability to form multiple H-bonds make arginine ideal for binding negatively charged groups. For this reason, arginine prefers to be on the outside of the proteins where it can interact with the polar environment. Incorporated in proteins, arginine can also be converted to citrulline by PAD enzymes. In addition, arginine can be methylated by protein methyltransferases.

As a precursor

Arginine is the immediate precursor of NO, urea, ornithine and agmatine; is necessary for the synthesis of creatine; and can also be used for the synthesis of polyamines (mainly through ornithine and to a lesser degree through agmatine), citrulline, and glutamate. As a precursor of nitric oxide, arginine may have a role in the treatment of some conditions where vasodilation is required.[2] The presence of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), a close relative, inhibits the nitric oxide reaction; therefore, ADMA is considered a marker for vascular disease, just as L-arginine is considered a sign of a healthy endothelium.

Treatment of herpes simplex virus

A low ratio of arginine to lysine may be of benefit in the treatment of herpes simplex virus. For more information, refer to Herpes - Treatment.

Possible increased risk of death after supplementation following heart attack

A clinical trial found that patients taking an L-arginine supplement following a heart attack didn't improve in their vascular tone or their hearts' ability to pump. In fact, six more patients who were taking L-arginine died than those taking a placebo and the study was stopped early with the recommendation the supplement not be used by heart attack patients.[13][14][15] The supplement is still widely marketed.

Potential medical uses

Lung inflammation and asthma

The Mayo Clinic web page on L-arginine reports that inhalation of L-arginine can increase lung inflammation and worsen asthma.[16]

Growth hormone

Arginine may stimulate the secretion of growth hormone,[17] and is used in growth hormone stimulation tests.[18]

MELAS syndrome

Several trials delved into effects of L-arginine in MELAS syndrome, a mitochondrial disease.[19][20][21][22]

Sepsis

Cellular arginine biosynthetic capacity determined by activity of argininosuccinate synthetase (AS) is induced by the same mediators of septic response — endotoxin and cytokines — that induce nitric oxide synthase (NOS), the enzyme responsible for nitric oxide synthesis.[23]

Malate salt

The malate salt of arginine can also be used during the treatment of alcoholic hepatitis and advanced cirrhosis.[24]

See also

AAKG

References

- ↑ IUPAC-IUBMB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature. "Nomenclature and Symbolism for Amino Acids and Peptides". Recommendations on Organic & Biochemical Nomenclature, Symbols & Terminology etc. http://www.chem.qmul.ac.uk/iupac/AminoAcid/. Retrieved 2007-05-17.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Tapiero, H.; et al. (November 2002). "L-Arginine". Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy 56 (9): 439–445 REVIEW. PMID 12481980.

- ↑ Wu, G.; et al. (August 2004). "Arginine deficiency in preterm infants: biochemical mechanisms and nutritional implications". Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 15 (8): 332–451 REVIEW. doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2003.11.010. PMID 15302078.

- ↑ "L-Arginine Supplements Nitric Oxide Scientific Studies Food Sources". http://www.keysupplements.com/articles/L-Arginine-Supplements-Nitric-Oxide-Scientific-Studies.htm. Retrieved 2007-02-20.

- ↑

Enzymes of arginine metabolism J Nutr. 2004 Oct; 134(10 Suppl): 2743S-2747S; PMID 15465778 Free text

Enzymes of arginine metabolism J Nutr. 2004 Oct; 134(10 Suppl): 2743S-2747S; PMID 15465778 Free text - ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Stechmiller, J.K.; et al. (February 2005). "Arginine supplementation and wound healing". Nutrition in Clinical Practice 20 (13): 52–61 REVIEW. doi:10.1177/011542650502000152. PMID 16207646.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Witte, M.B.; Barbul, A (Nov-Dec 2003). "Arginine physiology and its implication for wound healing". Wound Repair and Regeneration 11 (6): 419–423 REVIEW. doi:10.1046/j.1524-475X.2003.11605.x. PMID 14617280.

- ↑ Stanislavov, R. and Nikolova. 2003. Treatment of Erectile Dysfunction with Pycnogenol and L-arginine. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 29(3): 207 – 213.

- ↑ Lebret, T., Hervéa, J. M., Gornyb, P., Worcelc, M. and Botto, H. 2002. Efficacy and Safety of a Novel Combination of L-Arginine Glutamate and Yohimbine Hydrochloride: A New Oral Therapy for Erectile Dysfunction. European Urology 41(6): 608-613.

- ↑ Andrew, P.J.; Myer, B. (August 15 1999). "Enzymatic function of nitric oxide synthases". Cardiovascular Research 43 (3): 521–531 REVIEW. doi:10.1016/S0008-6363(99)00115-7. PMID 10690324. [1]

- ↑ Gokce, N.. (October 2004). "L-Arginine and hypertension". Journal of Nutrition 134 (10 Suppl): 2807S–2811S REVIEW. PMID 15465790.

- ↑ Rajapakse, N.W.; et al. (December 2008). "Exogenous L-arginine ameliorates angiotensin II-induced hypertension and renal damage in rats". Hypertension 52 (6): 1084–1090. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.114298. PMID 18981330. [2]

- ↑ Medical College of Georgia. "Diabetes Makes It Hard For Blood Vessels To Relax." ScienceDaily 1 February 2008. 1 February 2008

- ↑ Arginine Therapy in Acute Myocardial Infarction JAMA. 2006 Jan; Vol.295 #1: 58-64; PMID 16391217 Abstract

- ↑ This study has been discussed in some detail in : "Reverse Heart Disease Now" by Stephen T Sinatra MD and James C Roberts MD, publ. Wiley 2006 ISBN 0-471-74704-1 at pp 111-113.

- ↑ Sapienza MA, Kharitonov SA, Horvath I, Chung KF, Barnes PJ. "Effect of inhaled L-arginine on exhaled nitric oxide in normal and asthmatic subjects." Thorax. 1998 Mar;53(3):172-5.

- ↑ Alba-Roth J, Müller O, Schopohl J, von Werder K (1988). "Arginine stimulates growth hormone secretion by suppressing endogenous somatostatin secretion". J Clin Endocrinol Metab 67 (6): 1186–9. doi:10.1210/jcem-67-6-1186. PMID 2903866.

- ↑ U.S. National Library of Medicine (September 2009). Growth hormone stimulation test

- ↑ Koga Y, Akita Y, Junko N, Yatsuga S, Povalko N, Fukiyama R, Ishii M, Matsuishi T (June 2006). "Endothelial dysfunction in MELAS improved by l-arginine supplementation". Neurology 66 (11): 1766–9. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000220197.36849.1e. PMID 16769961. http://www.neurology.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=16769961.

- ↑ Koga Y (November 2008). "[L-arginine therapy on MELAS]" (in Japanese). Rinsho Shinkeigaku 48 (11): 1010–2. PMID 19198147.

- ↑ Koga Y, Akita Y, Nishioka J, Yatsuga S, Povalko N, Katayama K, Matsuishi T (2007). "MELAS and L-arginine therapy". Mitochondrion 7 (1-2): 133–9. doi:10.1016/j.mito.2006.11.006. PMID 17276739. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1567-7249(06)00227-3.

- ↑ Finsterer J (November 2009). "Management of mitochondrial stroke-like-episodes". Eur. J. Neurol. 16 (11): 1178–84. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02789.x. PMID 19780807. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/resolve/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=1351-5101&date=2009&volume=16&issue=11&spage=1178.

- ↑ MORRIS SM (1995). ROLE OF ARGININE SYNTHESIS IN SURGICAL SEPSIS. http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/. Retrieved 2010-02-22.

- ↑ Tissot-Favre A, Brette R (May-June 1970). "Therapeutic effects of arginine malate in alcoholic cirrhosis". Therapie 25 (3): 629–33. PMID 5431854.

External links

- NIST Chemistry Webbook

- Mayo Clinic discussion of Arginine.

- National Institute of Health discussion of Arginine.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||