Henry Kissinger

| Henry Kissinger | |

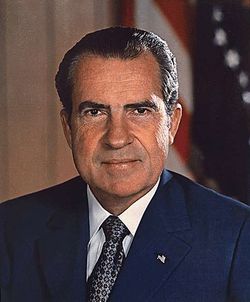

Henry Kissinger in 1976. |

|

|

|

|

|---|---|

| In office September 22, 1973 – January 20, 1977 |

|

| President | Richard Nixon Gerald Ford |

| Deputy | Kenneth Rush Robert S. Ingersoll Charles W. Robinson |

| Preceded by | William P. Rogers |

| Succeeded by | Cyrus Vance |

|

8th US National Security Advisor

|

|

| In office January 20, 1969 – November 3, 1975 |

|

| President | Richard Nixon Gerald Ford |

| Preceded by | Walt Rostow |

| Succeeded by | Brent Scowcroft |

|

|

|

| Born | Heinz Alfred Kissinger |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Ann Fleischer (1949-1964) Nancy Maginnes (1974-present) |

| Alma mater | City College of New York Harvard University |

| Profession | Diplomat Academician |

| Religion | Jewish |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Service/branch | US Army |

| Rank | Sergeant |

| Unit | 970th Counter Intelligence Corps |

Henry Alfred Kissinger (pronounced /ˈkɪsɪndʒər/;[1] born May 27, 1923) is a German-born American political scientist, diplomat, and recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize. He served as National Security Advisor and later concurrently as Secretary of State in the administrations of Presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford. After his term, his opinion was still sought out by many following presidents.

A proponent of Realpolitik, Kissinger played a dominant role in United States foreign policy between 1969 and 1977. During this period, he pioneered the policy of détente with the Soviet Union, orchestrated the opening of relations with the People's Republic of China, and negotiated the Paris Peace Accords, ending American involvement in the Vietnam War. His role in the bombing of Cambodia and other American interventions abroad during this period remains controversial.

Kissinger is still a controversial figure today.[2] He remains a regular participant in meetings of the annual invitation-only Bilderberg Group.[3] He was honored as the first recipient of the Ewald von Kleist Award of the Munich Conference on Security Policy and currently serves as the chairman of Kissinger Associates, an international consulting firm.

Contents |

Early and personal life

Early life

Kissinger was born Heinz Alfred Kissinger in Fürth, Bavaria, to a family of German Jews. His father, Louis Kissinger (1887–1982) was a schoolteacher. His mother, Paula Stern Kissinger (1901–1998), was a homemaker. Kissinger has a younger brother, Walter Kissinger. The surname Kissinger was adopted in 1817 by his great-great-grandfather Meyer Löb, after the city of Bad Kissingen.[4] In 1938, fleeing Nazi persecution, his family moved to New York.

Kissinger spent his high school years in the Washington Heights section of upper Manhattan as part of the German Jewish immigrant community there. Although Kissinger assimilated quickly into American culture, he never lost his pronounced Frankish accent, due to childhood shyness that made him hesitant to speak.[5][6] Following his first year at George Washington High School, he began attending school at night and worked in a shave brush factory during the day.[5]

Following high school, Kissinger enrolled in the City College of New York, studying accounting. He excelled academically as a part-time student, continuing to work while enrolled. His studies were interrupted in early 1943, when he was drafted into the U.S. Army.[7]

Family life

Kissinger first married Ann Fleischer, with whom he had two children, Elizabeth and David. They divorced in 1964. Ten years later, he married Nancy Maginnes.[8] They now live in Kent, Connecticut and New York City. David was an executive with NBC Universal before being tapped as the head of Conaco, Conan O'Brien's production company.[9]

Army experience

Kissinger underwent basic training at Camp Croft in Spartanburg, South Carolina, where he was naturalized upon arrival. The Army sent him to study engineering at Lafayette College, Pennsylvania, but the program was canceled, and Kissinger was reassigned to the 84th Infantry Division. There, he made the acquaintance of Fritz Kraemer, a fellow emigrant from Germany who, noting Kissinger's fluency in German and his intellect, arranged for him to be assigned to the military intelligence section of the division. Kissinger saw combat with the division, and volunteered for hazardous intelligence duties during the Battle of the Bulge.[10]

During the American advance into Germany, Kissinger was assigned to de-Nazify the city of Krefeld, owing to a lack of German speakers on the division's intelligence staff. Kissinger relied on his knowledge of German society to remove the obvious Nazis and restore a working civilian administration, a task he accomplished in 8 days.[11] Kissinger was then reassigned to the Counter Intelligence Corps, with the rank of Sergeant. He was given charge of a team in Hanover assigned to tracking down Gestapo officers and other saboteurs, for which he was awarded the Bronze Star.[12] In June 1945, Kissinger was made commandant of a CIC detachment in the Bergstraße district of Hesse, with responsibility for de-Nazification of the district. Although he possessed absolute authority and powers of arrest, Kissinger took care to avoid abuses against the local population by his command.[13]

In 1946, Kissinger was reassigned to teach at the European Command Intelligence School at Camp King, continuing to serve in this role as a civilian employee following his separation from the Army.[14][15]

Academic career

Henry Kissinger received his B.A. degree summa cum laude at Harvard College in 1950, where he studied under William Yandell Elliott.[16] He received his M.A. and Ph.D. degrees at Harvard University in 1952 and 1954, respectively. In 1952, while still at Harvard, he served as a consultant to the Director of the Psychological Strategy Board.[17] His doctoral dissertation was titled "Peace, Legitimacy, and the Equilibrium (A Study of the Statesmanship of Castlereagh and Metternich)."

Kissinger remained at Harvard as a member of the faculty in the Department of Government and at the Center for International Affairs. He became Associate Director of the latter in 1957. In 1955, he was a consultant to the National Security Council's Operations Coordinating Board.[17] During 1955 and 1956, he was also Study Director in Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy at the Council on Foreign Relations. He released his Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy the following year.[18] From 1956 to 1958 he worked for the Rockefeller Brothers Fund as director of its Special Studies Project.[17] He was Director of the Harvard Defense Studies Program between 1958 and 1971. He was also Director of the Harvard International Seminar between 1951 and 1971. Outside of academia, he served as a consultant to several government agencies, including the Operations Research Office, the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, and the Department of State, and the Rand Corporation, a think-tank.[17]

Keen to have a greater influence on US foreign policy, Kissinger became a supporter of, and advisor to, Nelson Rockefeller, Governor of New York, who sought the Republican nomination for President in 1960, 1964 and 1968. After Richard Nixon won the presidency in 1968, he made Kissinger National Security Advisor.

Foreign policy

Kissinger served as National Security Advisor and Secretary of State under President Richard Nixon, and continued as Secretary of State under Nixon's successor Gerald Ford.[19]

A proponent of Realpolitik, Kissinger played a dominant role in United States foreign policy between 1969 and 1977. In that period, he extended the policy of détente. This policy led to a significant relaxation in U.S.-Soviet tensions and played a crucial role in 1971 talks with Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai. The talks concluded with a rapprochement between the United States and the People's Republic of China, and the formation of a new strategic anti-Soviet Sino-American alignment. He was awarded the 1973 Nobel Peace Prize for helping to establish a ceasefire and US withdrawal from Vietnam. The ceasefire, however, was not durable.[20] Kissinger favored the maintenance of friendly diplomatic relationships with right-wing military dictatorships in the Southern Cone and elsewhere in Latin America as well as the intervention in these countries to establish these governments.

Détente and the opening to China

As National Security Advisor under Nixon, Kissinger pioneered the policy of détente with the Soviet Union, seeking a relaxation in tensions between the two superpowers. As a part of this strategy, he negotiated the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (culminating in the SALT I treaty) and the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty with Leonid Brezhnev, General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party. Negotiations about strategic disarmament were originally supposed to start under the Johnson Administration but were postponed in protest to the invasion by Warsaw Pact troops of Czechoslovakia in August 1968.

Kissinger sought to place diplomatic pressure on the Soviet Union. He made two trips to the People's Republic of China in July and October, 1971 (the first of which was made in secret) to confer with Premier Zhou Enlai, then in charge of Chinese foreign policy. This paved the way for the groundbreaking 1972 summit between Nixon, Zhou, and Communist Party of China Chairman Mao Zedong, as well as the formalization of relations between the two countries, ending 23 years of diplomatic isolation and mutual hostility. The result was the formation of a tacit strategic anti-Soviet alliance between China and the United States. While Kissinger's diplomacy led to economic and cultural exchanges between the two sides and the establishment of Liaison Offices in the Chinese and American capitals, with serious implications for Indochinese matters, full normalization of relations with the People's Republic of China would not occur until 1979, because the Watergate scandal overshadowed the latter years of the Nixon presidency and because the United States continued to recognize the Republic of China government on Taiwan.

Vietnam War

Kissinger's involvement in Indochina started prior to his appointment as National Security Adviser to Nixon. While still at Harvard, he had worked as a consultant on foreign policy to both the White House and State Department. Kissinger says that "In August 1965... [Henry Cabot Lodge], an old friend serving as Ambassador to Saigon, had asked me to visit Vietnam as his consultant. I toured Vietnam first for two weeks in October and November 1965, again for about ten days in July 1966, and a third time for a few days in October 1966... Lodge gave me a free hand to look into any subject of my choice". He became convinced of the meaninglessness of military victories in Vietnam, "...unless they brought about a political reality that could survive our ultimate withdrawal".[21] In a 1967 peace initiative, he would mediate between Washington and Hanoi.

Nixon had been elected in 1968 on the promise of achieving "peace with honor" and ending the Vietnam War. In office, and assisted by Kissinger, Nixon implemented a policy of Vietnamization that aimed to gradually withdraw US troops while expanding the combat role of the enabling South Vietnamese Army so that it would be capable of independently defending its regime against the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam, a Communist guerrilla organization, and North Vietnamese army (Vietnam People's Army or PAVN). Kissinger played a key role in a secret bombing campaign in Cambodia to disrupt PAVN and Viet Cong units launching raids into South Vietnam from within Cambodia's borders and resupplying their forces by using the Ho Chi Minh trail and other routes, as well as the 1970 Cambodian Incursion and subsequent widespread bombing of Cambodia. The bombing campaign contributed to the chaos of the Cambodian Civil War, which saw the forces of dictator Lon Nol unable to retain foreign support to combat the growing Khmer Rouge insurgency that would overthrow him in 1975.[22][23]

Along with North Vietnamese Politburo Member Le Duc Tho, Kissinger was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize on December 10, 1973, for their work in negotiating the ceasefires contained in the Paris Peace Accords on "Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam," signed the January previous.[20] Tho rejected the award, telling Kissinger that peace had not been really restored in South Vietnam.[24] Kissinger wrote to the Nobel Committee that he accepted the award "with humility."[25][26] The conflict continued until an invasion of the South by the North Vietnamese Army resulted in a North Vietnamese victory in 1975 and the subsequent progression of the Pathet Lao in Laos towards figurehead status.

1971 Liberation War of Bangladesh

Under Kissinger's guidance, the United States government supported Pakistan in the Liberation War of Bangladesh in 1971. Kissinger was particularly concerned about the expansion of Soviet influence in South Asia as a result of a treaty of friendship recently signed by India and the Soviet Union, and sought to demonstrate to the People's Republic of China (Pakistan's ally and an enemy of both India and the Soviet Union) the value of a tacit alliance with the United States.[27]

In recent years, Kissinger has come under fire for private comments he made to Nixon during the Bangladesh-Pakistan War in which he described then-Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi as a "bitch" and a "witch". He also said "The Indians are bastards," shortly before the war.[28] Kissinger has since expressed his regret over the comments.[29]

1973 Yom Kippur War

In 1973, Kissinger negotiated the end to the Yom Kippur War, which had begun on October 6, 1973 when Egypt and Syria attacked Israel. Kissinger has published lengthy and dramatic telephone transcripts from this period in the 2002 book Crisis. One week later, under Nixon's direction, and against Kissinger's initial opposition,[30] the US military conducted the largest military airlift in history to aid Israel on October 12, 1973. US action contributed to the 1973 oil crisis in the United States and its Western European allies, which ended in March 1974.

Israel regained the territory it lost in the early fighting and gained new territories from Syria and Egypt, including land in Syria east of the previously captured Golan Heights, and additionally on the western bank of the Suez Canal, although they did lose some territory on the eastern side of the Suez Canal that had been in Israeli hands since the end of the Six Day War. Kissinger pressured the Israelis to cede some of the newly captured land back to its Arab neighbours, contributing to the first phases of Israeli-Egyptian non-aggression. The move saw a warming in US–Egyptian relations, bitter since the 1950s, as the country moved away from its former independent stance and into a close partnership with the United States. The peace was finalized in 1978 when U.S. President Jimmy Carter mediated the Camp David Accords, during which Israel returned the Sinai Peninsula in exchange for an Egyptian agreement to recognize the state of Israel.

Latin American policy

The United States continued to recognize and maintain relationships with non-left-wing governments, democratic and authoritarian alike. John F. Kennedy's Alliance for Progress was ended in 1973. In 1974, negotiations about new settlement over Panama Canal started. They eventually led to the Torrijos-Carter Treaties and handing the Canal over to Panamanian control.

Kissinger initially supported the normalization of United States-Cuba relations, broken since 1961 (all U.S.–Cuban trade was blocked in February 1962, a few weeks after the exclusion of Cuba from the Organization of American States because of US pressure). However, he quickly changed his mind and followed Kennedy's policy. After the involvement of the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces in the liberation struggles in Angola and Mozambique, Kissinger said that unless Cuba withdrew its forces relations would not be normalized. Cuba refused.

Intervention in Chile

Chilean Socialist Party presidential candidate Salvador Allende was elected by a plurality in 1970, causing serious concern in Washington, D.C. due to his openly socialist and pro-Cuban politics. The Nixon administration authorized the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to instigate a military coup that would prevent Allende's inauguration, but the plan was not successful.[31] The extent of Kissinger's involvement in or support of these plans is a subject of controversy.[32]

United States-Chile relations remained frosty during Salvador Allende's tenure, following the complete nationalization of the partially U.S.-owned copper mines and the Chilean subsidiary of the U.S.-based ITT Corporation, as well as other Chilean businesses. The U.S. implemented economic sanctions, claiming that the Chilean government had greatly undervalued fair compensation for the nationalization by subtracting what it deemed "excess profits". The CIA provided education for the military officers directly involved in the coup against Allende,[33] and funding for the mass anti-government strikes in 1972 and 1973; during this period, Kissinger made several controversial statements regarding Chile's government, stating that "the issues are much too important for the Chilean voters to be left to decide for themselves" and "I don't see why we need to stand by and watch a country go Communist due to the irresponsibility of its people."[34]

On September 11, 1973, Allende committed suicide during a military coup launched by Army Commander-in-Chief Augusto Pinochet, who became President.[35] A document released by the CIA in 2000 titled "CIA Activities in Chile" revealed that the CIA actively supported the military junta after the overthrow of Allende and that it made many of Pinochet's officers into paid contacts of the CIA or US military, even though many were known to be involved in notorious human rights abuses,[36] until Democratic challenger Jimmy Carter defeated President Gerald Ford in 1976.

On September 16, 1973, five days after Pinochet had assumed power, the following exchange about the coup took place between Kissinger and President Nixon:

- Nixon: Nothing new of any importance or is there?

- Kissinger: Nothing of very great consequence. The Chilean thing is getting consolidated and of course the newspapers are bleeding because a pro-Communist government has been overthrown.

- Nixon: Isn't that something. Isn't that something.

- Kissinger: I mean instead of celebrating – in the Eisenhower period we would be heroes.

- Nixon: Well we didn't – as you know – our hand doesn't show on this one though.

- Kissinger: We didn't do it. I mean we helped them. [garbled] created the conditions as great as possible.

- Nixon: That is right. And that is the way it is going to be played.[37]

There was information that the Chileans were planning Operation Condor in 1976. Kissinger canceled a letter that was to be sent to Chile warning them against carrying out any political assassinations. Orlando Letelier was then assassinated in Washington, D.C. with a car bomb on September 21, 1976.[38]

Intervention in Argentina

Kissinger took a similar line as he had toward Chile when the Argentine military, led by Jorge Videla, toppled the democratic government of Isabel Perón in 1976 and consolidated power, launching brutal reprisals and "disappearances" against political opponents. During a meeting with Argentine foreign minister César Augusto Guzzetti, Kissinger assured him that the United States was an ally, but urged him to "get back to normal procedures" quickly before the U.S. Congress reconvened and had a chance to consider sanctions.

Africa

In 1974 a leftist military coup overthrew the Caetano government in Portugal in the Carnation Revolution. The National Salvation Junta, the new government, quickly granted Portugal's colonies independence. Cuban troops in Angola supported the left-wing Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) in its fight against right-wing UNITA and FNLA rebels during the Angolan Civil War (1975–2002). Kissinger supported FNLA, led by Holden Roberto, and UNITA, led by Jonas Savimbi, the Mozambican National Resistance (RENAMO) insurgencies, as well as the CIA-supported invasion of Angola by South African troops. The FNLA was defeated and UNITA was forced to take its fight into the bush. Only under Reagan's presidency would U.S. support for UNITA return.

In September 1976 Kissinger was actively involved in negotiations regarding the Rhodesian Bush War. Kissinger, along with South Africa's Prime Minister John Vorster, pressured Rhodesian Prime Minister Ian Smith to hasten the transition to black majority rule in Rhodesia. With FRELIMO in control of Mozambique and even South Africa withdrawing its support, Rhodesia's isolation was nearly complete. According to Smith's autobiography, Kissinger told Smith of Mrs. Kissinger's admiration for him, but Smith stated that he thought Kissinger was asking him to sign Rhodesia's "death certificate". Kissinger, bringing the weight of the United States, and corralling other relevant parties to put pressure on Rhodesia, hastened the end of minority-rule.

East Timor

The Portuguese decolonization process brought US attention to the former Portuguese colony of East Timor, which lies within the Indonesian archipelago and declared its independence in 1975. Indonesian president Suharto was a strong US ally in Southeast Asia and began to mobilize the Indonesian army, preparing to annex the nascent state, which had become increasingly dominated by the popular leftist FRETILIN party. In December 1975, Suharto discussed the invasion plans during a meeting with Kissinger and President Ford in the Indonesian capital of Jakarta. Both Ford and Kissinger made clear that US relations with Indonesia would remain strong and that it would not object to the proposed annexation. US arms sales to Indonesia continued, and Suharto went ahead with the annexation plan.

Later roles

Shortly after Kissinger left office in 1977, he was offered an endowed chair at Columbia University. There was significant student opposition to the appointment,[39] which eventually became a subject of significant media commentary[40] Columbia cancelled the appointment as a result.

Kissinger was then appointed to Georgetown University's Center for Strategic and International Studies.[41] Kissinger published a dialogue with the Japanese philosopher, Daisaku Ikeda, On Peace, Life and Philosophy. He taught at Georgetown's Edmund Walsh School of Foreign Service for several years in the late 1970s. In 1982, Kissinger founded a consulting firm, Kissinger Associates, and is a partner in affiliate Kissinger McLarty Associates with Mack McLarty, former chief of staff to President Bill Clinton.[42] He also serves on board of directors of Hollinger International, a Chicago-based newspaper group,[43] and as of March 1999, he also serves on board of directors of Gulfstream Aerospace.[44]

In 1978, Kissinger was named chairman of the North American Soccer League board of directors.[45] From 1995 to 2001, he served on the board of directors for Freeport-McMoRan, a multinational copper and gold producer with significant mining and milling operations in Papua, Indonesia.[46] In February 2000, then-president of Indonesia Abdurrahman Wahid appointed Kissinger as a political advisor. He also serves as an honorary advisor to the United States-Azerbaijan Chamber of Commerce.

Role in U.S. foreign policy

Kissinger left office when a Democrat, former Governor of Georgia and "Washington outsider" Jimmy Carter, defeated Republican Gerald Ford in the 1976 presidential elections. Kissinger continued to participate in policy groups, such as the Trilateral Commission, and to maintain political consulting, speaking, and writing engagements.

In 2002, President George W. Bush appointed Kissinger to chair a committee to investigate the September 11 attacks. Kissinger stepped down as chairman on December 13, 2002 rather than reveal his client list, when queried about potential conflicts of interest.

The Balkans

In several articles of his and interviews that he gave during the Yugoslav wars, he criticized the United States' policies in the Balkans, among other things for the recognition of Bosnia and Herzegovina as a sovereign state, which he described as a foolish act.[47] Most importantly he dismissed the notion of Serbs, and Croats for that part, being aggressors or separatist, saying that "they can't be separating from something that has never existed".[48]

In addition, he repeatedly warned the West of implicating itself in a conflict that has its roots at least hundreds of years back in time, and said that the West would do better if it allowed the Serbs and Croats to join their respective countries.[48]

Kissinger was similarly critical of Western involvement in Kosovo. In particular, he held a disparaging view of the Rambouillet Agreement:

The Rambouillet text, which called on Serbia to admit NATO troops throughout Yugoslavia, was a provocation, an excuse to start bombing. Rambouillet is not a document that any Serb could have accepted. It was a terrible diplomatic document that should never have been presented in that form.—Henry Kissinger, Daily Telegraph, June 28, 1999

However, as the Serbs did not accept the Rambouillet text and NATO bombings started, he opted for a continuation of the bombing as NATO's credibility was now at stake, but dismissed the usage of ground forces, claiming that it was not worth it.[49]

Iraq

In 2006, it was reported in the book State of Denial by Bob Woodward that Kissinger was meeting regularly with President George W. Bush and Vice President Dick Cheney to offer advice on the Iraq War.[50] Kissinger confirmed in recorded interviews with Woodward[51] that the advice was the same as he had given in an August 12, 2005 column in The Washington Post: "Victory over the insurgency is the only meaningful exit strategy."[52]

In a November 19, 2006 interview at BBC Sunday AM, Kissinger said, when asked whether there is any hope left for a clear military victory in Iraq, "If you mean by 'military victory' an Iraqi Government that can be established and whose writ runs across the whole country, that gets the civil war under control and sectarian violence under control in a time period that the political processes of the democracies will support, I don't believe that is possible... I think we have to redefine the course. But I don't believe that the alternative is between military victory as it had been defined previously, or total withdrawal."[53]

In an April 3, 2008 interview by Peter Robinson of the Hoover Institution, Kissinger re-iterated that even though he supported the 2003 invasion of Iraq he thought that the Bush administration rested too much of the case for war on Saddam's supposed weapons of mass destruction. Robinson noted that Kissinger had criticized the administration for invading with too few troops, for disbanding the Iraqi Army, and for mishandling relations with certain allies.[54]

Southwest Asia

After apologizing for his use of the word 'bitch' in reference to Mrs. Indira Gandhi, Kissinger met India's main Opposition Leader Lal Krishna Advani in early October 2007 and lobbied for the support of his Bharatiya Janata Party for the Indo-US civilian nuclear agreement.

Kissinger was present at the opening ceremony of the Beijing Summer Olympics. He was also in the Chinese capital to attend the inauguration of the new US Embassy complex.

Kissinger said in April 2008 that "India has parallel objectives to the United States" and he called it an ally of the U.S.[54]

Iran

Kissinger's position on this issue of U.S.-Iran talks was reported by the Tehran Times to be that "Any direct talks between the U.S. and Iran on issues such as the nuclear dispute would be most likely to succeed if they first involved only diplomatic staff and progressed to the level of secretary of state before the heads of state meet."[55]

Public perception

Kissinger, like the rest of the Nixon administration, was unpopular with the anti-war political left, especially after his central role in the U.S. bombing of neutral Cambodia was revealed. Kissinger was also opposed by more ideological elements of the Republican foreign policy establishment for his policy of détente and accommodation with the Soviets.

However, few doubted his intellect and diplomatic skill, and he became one of the better-liked members of the Nixon administration, though many Americans came to view Kissinger's talents as increasingly cynical and self-serving. Kissinger was not connected with the Watergate scandal that would eventually ruin Nixon and many of his closest aides, and this greatly improved Kissinger's reputation as he became known as the "clean man" of the bunch.

At the height of Kissinger's prominence, he was even regarded as something of a sex symbol due to his prominent dating life.[56] He was quoted as saying "Power is the ultimate aphrodisiac".[57]

Subsequent to leaving office, numerous efforts have been made to charge Kissinger personally for the perceived injustices of American foreign policy during his tenure in office. These charges have at times inconvenienced his travels.[58]

In film & television

Kissinger has shied away from mainstream media and cable talk shows. Recently, he granted a rare interview to the producers of a documentary examining the underpinnings of the 1979 peace treaty between Israel and Egypt entitled "Back Door Channels: The Price of Peace".[59] In the film, a candid Kissinger reveals how close he felt the world was to nuclear war during the 1973 Yom Kippur War launched by Egypt and Syria against Israeli forces in the territories Israel occupied from them as a result of the 1967 War.

Awards, honors and associations

In 1973, Kissinger and Le Duc Tho were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for the Paris Peace Accords of 1973, "intended to bring about a cease-fire in the Vietnam war and a withdrawal of the American forces," while serving as the United States Secretary of State. Unlike Tho, who refused it because Vietnam was still at war, Kissinger accepted it.

On January 13, 1977, Kissinger was presented with the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Gerald Ford.

In 1995, he was appointed an honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire.[60]

In 1998, Kissinger became an honorary citizen of Fürth, Germany, his hometown. He has been a life-long supporter of the Spielvereinigung Greuther Fürth football club and is now an honorary member. He served as Chancellor of the College of William and Mary from February 10, 2001 to the summer of 2005.

In April 2006, Kissinger received the Woodrow Wilson Award for Public Service from the Woodrow Wilson Center of the Smithsonian Institution.

In June 2007, Kissinger received the Hopkins-Nanjing Award for his contributions to reestablishing Sino–American relations. This award was presented by the presidents of Nanjing University, Chen Jun and of Johns Hopkins University, William Brody, during the 20th anniversary celebration of the Johns Hopkins University—Nanjing University Center for Chinese and American Studies also known as the Hopkins-Nanjing Center.

In September 2007, Kissinger was honored as Grand Marshal of the German-American Steuben Parade in New York City. He was celebrated by tens of thousands of spectators on Fifth Avenue. Former German Chancellor Helmut Kohl was supposed to be a co-Grand Marshal but had to cancel due to health problems. Kohl was represented by Klaus Scharioth, German Ambassador in Washington, who led the Steuben Parade with Kissinger.

Kissinger is known to be a member of the following groups:

- Bohemian Grove[61]

- Council on Foreign Relations[62]

- Aspen Institute[63]

- Bilderberg Group[64]

Bibliography

Memoirs

- 1979. The White House Years. ISBN 0-316-49661-8

- 1982. Years of Upheaval. ISBN 0-316-28591-9

- 1999. Years of Renewal. ISBN 0-684-85571-2

Public policy

- 1957. Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy. ISBN 0-865-31745-3 (1984 edition)

- 1961. The Necessity for Choice: Prospects of American Foreign Policy. ISBN 0-06-012410-5

- 1965. The Troubled Partnership: A Re-Appraisal of the Atlantic Alliance. ISBN 0-07-034895-2

- 1969. American Foreign Policy: Three essays. ISBN 0-297-17933-0

- 1973. A World Restored: Metternich, Castlereagh and the Problems of Peace, 1812-22. ISBN 0-395-17229-2

- 1981. For the Record: Selected Statements 1977-1980. ISBN 0-316-49663-4

- 1985 Observations: Selected Speeches and Essays 1982-1984. ISBN 0-316-49664-2

- 1994. Diplomacy. ISBN 067165991X

- 1999. Kissinger Transcripts: The Top Secret Talks With Beijing and Moscow (Henry Kissinger, William Burr). ISBN 1-56584-480-7

- 2001. Does America Need a Foreign Policy?: Toward a Diplomacy for the 21st Century. ISBN 0684855674

- 2002. Vietnam: A Personal History of America's Involvement in and Extrication from the Vietnam War. ISBN 0-7432-1916-3

- 2003. Crisis: The Anatomy of Two Major Foreign Policy Crises: Based on the Record of Henry Kissinger's Hitherto Secret Telephone Conversations. ISBN 0-7432-4910-0

Footnotes

- ↑ "Kissinger - Definition from the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary". Merriam-Webster. http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Kissinger. Retrieved 2009-10-23.

- ↑ A press release issued by the 45th Munich Conference on Security Policy on February 8, 2009 declared "[H]is voice continues to bear weight and authority throughout the globe." see [1] Munich Security Conference - February 6, 2009 Press Release

- ↑ Oliver, Mark. The Bilderberg group. The Guardian. 4 June 2004.

- ↑ "Die Kissingers in Bad Kissingen" (in german). Bayerischer Rundfunk. June 2, 2005. http://www.br-online.de/land-und-leute/artikel/0506/02-kissinger/index.xml?theme=print. Retrieved 2007-02-03.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Isaacson, pp 37.

- ↑ "Bygone Days: Complex Jew. Inside Kissinger's soul". Jerusalem Post. http://www.jpost.com/servlet/Satellite?cid=1198517217372&pagename=JPost%2FJPArticle%2FShowFull. Retrieved 2008-09-04.

- ↑ Isaacson, pp 38

- ↑ "Somebody to Come Home To". Time Magazine. April 8, 1974. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,908532,00.html.

- ↑ NBC Universal Television Studio (2005-05-25). "NBC Universal Television Studio Co-President David Kissinger Joins Conaco Productions as New President". Press release. http://www.thefutoncritic.com/news.aspx?id=20050525nuts02.

- ↑ Isaacson, pp 39-48.

- ↑ Isaacson, pp 48

- ↑ Isaacson, pp 49

- ↑ Isaacson, pp 53

- ↑ Isaacson, pp 55.

- ↑ "Henry Kissinger at Large, Part One". PBS. January 29, 2004. http://www.pbs.org/thinktank/transcript1138.html.

- ↑ Draper, Theodore (September 6, 1992). "Little Heinz And Big Henry". New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/books/98/12/06/specials/isaacson-kissinger.html?_r=1&oref=slogin. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 "Henry Kissinger - Biography". nobelprize.org. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/1973/kissinger-bio.html. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- ↑ Kissinger, Henry (1957). Nuclear weapons and foreign policy. Harper & Brothers. p. 455.

- ↑ "History of the National Security Council, 1947-1997". whitehouse.gov. http://www.whitehouse.gov/nsc/history.html. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "The Nobel Peace Prize 1973". Nobel Foundation. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/1973/press.html. Retrieved 2006-12-31.

- ↑ _White House Years_, pp. 231-32. Henry A. Kissinger. Boston: Little, Brown & co., 1979.

- ↑ Totten, Samuel; William S. Parsons, Israel W. Charny (2004). Century of genocide: critical essays and eyewitness accounts. Routledge. p. 349. ISBN 9780415944304. http://books.google.com/?id=5Ef8Hrx8Cd0C&pg=PA349&dq=US+bombing+cambodia+civil+war+result. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ↑ Smyth, Marie; Gillian Robinson, INCORE (2001). Researching violently divided societies: ethical and methodological issues. United Nations University Press. p. 93. ISBN 9789280810653. http://books.google.com/?id=ZWqNwsv6AIQC&pg=PA93&dq=US+bombing+cambodia+civil+war+result. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ↑ Le Duc Tho to Henry Kissinger, October 27, 1973.

- ↑ "The Nobel Peace Prize 1973: Presentation Speech by Mrs. Aase Lionaes, Chairman of the Nobel Committee of the Norwegian Storting". The Official Web Site of the Nobel Foundation. 1973-12-10. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/1973/press.html. Retrieved 2007-04-28. "'In his letter of November 2 to the Nobel Committee Henry Kissinger expresses his deep sense of this obligation. In the letter he writes among other things: "I am deeply moved by the award of the Nobel Peace Prize, which I regard as the highest honor one could hope to achieve in the pursuit of peace on this earth. When I consider the list of those who have been so honored before me, I can only accept this award with humility." ... This year Henry Kissinger was appointed Secretary-of-State in the United States. In his letter to the Committee he writes as follows: "I greatly regret that because of the press of business in a world beset by recurrent crisis I shall be unable to come to Oslo on December 10 for the award ceremony. I have accordingly designated Ambassador Byrne to represent me on that occasion.""

- ↑ Lundestad, Geir (March 15, 2001). "The Nobel Peace Prize 1901-2000". Nobel Foundation. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/articles/lundestad-review/index.html. Retrieved 2006-12-31.

- ↑ "The Tilt: The U.S. and the South Asian Crisis of 1971". National Security Archive. December 16, 2002. http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB79/. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- ↑ "150. Conversation Among President Nixon, the President’s Assistant for National Security Affairs (Kissinger), and the President’s Chief of Staff (Haldeman), Washington, November 5, 1971, 8:15–9:00 a.m.". Foreign Relations, 1969–1976 (U.S. Department of State) E-7 (19). 2005. http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ho/frus/nixon/e7/48529.htm. Retrieved December 30, 2006.

- ↑ "Kissinger regrets India comments". BBC. July 1, 2005. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/4640773.stm. Retrieved 2006-12-15.

- ↑ Siniver, Asaf (2008). Nixon, Kissinger, and U.S. Foreign Policy Making; The Machinery of Crisis. New York: Cambridge. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-521-89762-4 Hardback.

- ↑ "Church Report". U.S. Department of State. December 18, 1975. http://foia.state.gov/Reports/ChurchReport.asp. Retrieved 2006-11-20.

- ↑ Alleged Assassination Plots Involving Foreign Leaders (1975), Church Committee, pages 246–247 and 250–254.

- ↑ "see The Pinochet File". Gwu.edu. http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB110/index.htm. Retrieved 2010-03-10.

- ↑ ^ Cited in Richard R. Fagen, "The United States and Chile: Roots and Branches", Foreign Affairs, January 1975.

- ↑ Pike, John. "Allende's Leftist Regime". Federation of American Scientists. http://www.fas.org/irp/world/chile/allende.htm. Retrieved 2006-11-20.

- ↑ Peter Kornbluh, CIA Acknowledges Ties to Pinochet’s Repression Report to Congress Reveals U.S. Accountability in Chile, Chile Documentation Project, National Security Archive, September 19, 2000. Retrieved November 26, 2006.

- ↑ The Kissinger Telcons: Kissinger Telcons on Chile, National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 123, edited by Peter Kornbluh, posted May 26, 2004. This particular dialogue can be found at TELCON: September 16, 1973, 11:50 a.m. Kissinger Talking to Nixon. Retrieved November 26, 2006.

- ↑ "Cable Ties Kissinger to Chile Scandal". Associated Press in the New York Times. April 10, 2010. http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2010/04/10/us/AP-US-Kissinger-Chile.html?_r=1&hp. Retrieved 2010-04-10. "As secretary of state, Henry Kissinger canceled a U.S. warning against carrying out international political assassinations that was to have gone to Chile and two neighboring nations just days before a former ambassador was killed by Chilean agents on Washington's Embassy Row in 1976, a newly released State Department cable shows. Letelier was critical of Chilean government."

- ↑ "400 sign petition against offering Kissinger faculty post". Columbia Spectator. 1977-03-03.

- ↑ "Anthony Lewis of the Times also blasts former Secretary". Columbia Spectator. 1977-03-03.

- ↑ "CSIS". CSIS. 2007. http://www.csis.org/about/history/#1960. Retrieved 2007-01-20.

- ↑ "Council of the Americas Member". Council of the Americas. http://www.americas-society.org/coa/membersnetwork/Kissinger.html. Retrieved 2007-01-05.

- ↑ "Sun-Times Media Group Inc · 10-K/A". United States Securities and Exchange Commission. May 1, 2006. http://www.secinfo.com/$/SEC/Filing.asp?T=svrh.vs8_ffv. Retrieved 2006-12-29.

- ↑ "Gulfstream Aerospace Corp, Form 10-K". United States Securities and Exchange Commission. March 29, 1999. http://www.secinfo.com/dRaBu.64v.htm#1bum. Retrieved 2006-12-29.

- ↑ "Kissinger takes post as NASL chairman". the Victoria Advocate. October 5, 1978. http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=861&dat=19781005&id=A0IOAAAAIBAJ&sjid=T38DAAAAIBAJ&pg=5631,1106083. Retrieved 2010-03-21.

- ↑ "Freeport McMoran Inc · 10-K". United States Securities and Exchange Commission. March 31, 1994. http://www.secinfo.com/dsVQx.b1sw.htm#1nhw. Retrieved 2006-12-29.

- ↑ "Charlie Rose - A panel on the crisis in Bosnia". www.charlierose.com. 1994-11-28. http://www.charlierose.com/view/interview/7185. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 "Charlie Rose - An interview with Henry Kissinger". www.charlierose.com. 1995-09-14. http://www.charlierose.com/view/interview/6651. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ↑ "Charlie Rose - An hour with former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger". www.charlierose.com. 1999-04-12. http://www.charlierose.com/view/interview/4347. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ↑ "Bob Woodward: Bush Misleads On Iraq". CBS News. October 1, 2006. http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2006/09/28/60minutes/printable2047607.shtml. Retrieved 2006-12-29.

- ↑ Woodward, Bob (October 1, 2006). "Secret Reports Dispute White House Optimism". The Washington Post. pp. A01. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/09/30/AR2006093000293_pf.html. Retrieved 2006-12-29.

- ↑ Kissinger, Henry A. (August 12, 2005). "Lessons for an Exit Strategy". The Washington Post. pp. A19. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/08/11/AR2005081101756_pf.html. Retrieved 2006-12-29.

- ↑ Marr, Andrew (November 19, 2006). "US Policy on Iraq". BBC. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/programmes/sunday_am/6163050.stm. Retrieved 2006-12-29. (Transcript of a BBC Sunday AM interview.)

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Kissinger on War & More. Uncommon Knowledge. Filmed on April 3, 2008. Retrieved August 10, 2009.

- ↑ "Kissinger backs direct U.S. negotiations with Iran". The Tehran Times. September 27, 2008. http://www.tehrantimes.com/index_View.asp?code=165193. Retrieved 2008-09-27. (Transcript of a Bloomberg report interview.)

- ↑ "Henry Kissinger Off Duty." Time, February 7, 1972.

- ↑ "Henry A. Kissinger Quotes". Brainy Quote. http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/quotes/h/henryakis101648.html. Retrieved 2006-12-29.

- ↑ Why the law wants a word with Kissinger, Fairfax Digital, April 30, 2002 (English)

- ↑ "TV Festival 2009 : Opening Film". Tvfestival.net. http://www.tvfestival.net/content/Opening-Film/openUK.php. Retrieved 2010-03-10.

- ↑ Kissinger, Henry Alfred in Who's Who in the Twentieth Century, Oxford University Press, 1999

- ↑ [2] Vanity Fair: A Guide to the Bohemian Grove Published April 1, 2009 Retrieved on 2009-04-18.

- ↑ "History of CFR - Council on Foreign Relations". www.cfr.org. http://www.cfr.org/about/history/cfr/appendix.html. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ↑ "Lifetime Trustees". The Aspen Institute. www.aspeninstitute.org. http://www.aspeninstitute.org/about/leadership-board/lifetime-trustees. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ↑ "Western Issues Aired". The Washington Post. April 24, 1978. "The three-day 26th Bilderberg Meeting concluded at a secluded cluster of shingled buildings in what was once a farmer's field. Zbigniew Brzezinski, President Carter's national security adviser, Swedish Prime Minister Thorbjorrn Falldin, former secretary of state Henry Kissinger and NATO Commander Alexander M. Haig Jr. were among 104 North American and European leaders at the conference."

Further reading

Biographies

- 1973. Graubard, Stephen Richards, Kissinger: Portrait of a Mind. ISBN 0-393-05481-0

- 1974. Kalb, Marvin L. and Kalb, Bernard, Kissenger, ISBN 0-316-48221-8

- 1974. Schlafly, Phyllis, Kissinger on the Couch. Arlington House Publishers. ISBN 0-87000-216-3

- 1983. Hersh, Seymour, The Price of Power: Kissinger in the Nixon White House, Summit Books. ISBN 0671506889. (Awards: National Book Critics Circle, General Non-Fiction Award. Best Book of the Year: New York Times Book Review; Newsweek; San Francisco Chronicle)

- 1992. Isaacson, Walter. Kissinger: A Biography. New York. Simon & Schuster (updated, 2005). ISBN 0-671-66323-2

- 2004. Hanhimäki, Jussi. The Flawed Architect: Henry Kissinger and American Foreign Policy. ISBN 0-19-517221-3

- 2007. Kurz, Evi. Die Kissinger-Saga. ISBN 978-3-940405-70-8

- 2009. Kurz, Evi. The Kissinger-Saga - Walter and Henry Kissinger. Two Brothers from Fuerth, Germany. London. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-85675-7.

Other

- Benedetti, Amedeo, Lezioni di politica di Henry Kissinger. Linguaggio, pensiero ed aforismi del più abile politico di fine Novecento, Genova, Erga, 2005, ISBN 88-8163-391-4

- Berman, Larry, No peace, no honor. Nixon, Kissinger, and Betrayal in Vietnam, New York, NY u.a.: Free Press, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84968-2.

- Dallek, Robert, Nixon and Kissinger: Partners in Power. HarperCollins, 2007. ISBN 0060722304

- Hanhimäki, Jussi M., 'Dr. Kissinger' or 'Mr. Henry'? Kissingerology, Thirty Years and Counting', in: Diplomatic History, Vol. 27, Issue 5, pp. 637–76.

- Hitchens, Christopher, The Trial of Henry Kissinger, 2002. ISBN 1-85984-631-9

- Klitzing, Holger, The Nemesis of Stability. Henry A. Kissinger's Ambivalent Relationship with Germany. Trier: WVT 2007, ISBN 3884769421

- Morris, Roger, Uncertain Greatness: Henry Kissinger and American Foreign Policy. Harper and Row, ISBN 0-06-013097-0

- Schmidt, Helmut, On Men and Power: A Political Memoir.1990. ISBN 0-224-02715-8

- Schulzinger, Robert D. Henry Kissinger. Doctor of Diplomacy. New York: Columbia University Press, 1989. ISBN 0-231-06952-9

- Shawcross, William, Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon, and the Destruction of Cambodia (Revised edition October 2002) ISBN 0-8154-1224-X

- Thornton, Richard C., The Nixon-Kissinger Years: Reshaping of America's Foreign Policy. 1989. ISBN 0-88702-051-8

- Tucker, Nancy Bernkopf, Taiwan Expendable? Nixon and Kissinger Go to China, 2005. ISBN 9780231135658

External links

- Annotated Bibliography for Henry Kissinger from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

- Official Website of Henry A. Kissinger

- Henry Kissinger at the Internet Movie Database

- "Charlie Rose" A conversation with Henry Kissinger, December 16, 2008

- Henry Kissinger speaks at the Asia Society, NYC, February, 2007

- Kissinger's political donations

- NPR: Kissinger Speech at National Press Club. Towards the end [55:55], he responds to Hitchens.

- The Kissinger Saga. Henry and Walter: Two Brothers from Fuerth/Germany. Documentary, 90 min. (unabridged version), first time aired: Bayerischer Rundfunk (Bavarian Broadcasting Network), January 21, 2007. Summary

- Producer of 'The Kissinger-Saga, Walter and Henry Kissinger - Two Brothers from Fuerth/Germany'

- СССР TV: "In the wake of Kissinger's visit (1976)" (in Russian)

- Linkage and Arms Control. Interview conducted on November 26, 1986 for the War and Peace in the Nuclear Age series.

- Henry Kissinger interviewed by Mike Wallace on The Mike Wallace Interview July 13, 1958

| Legal offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Walt Rostow |

United States National Security Advisor 1969-1974 |

Succeeded by Brent Scowcroft |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by William P. Rogers |

United States Secretary of State Served under: Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford 1973-1977 |

Succeeded by Cyrus Vance |

| Honorary titles | ||

| Preceded by Margaret Thatcher |

Chancellor of The College of William & Mary 2000–2005 |

Succeeded by Sandra Day O'Connor |

|

|||||||

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||