Castor and Pollux

Castor (pronounced /ˈkæstər/; Latin: Castōr; Greek: Κάστωρ, Kastōr, "beaver") and Pollux (/ˈpɒləks/; Latin: Pollūx) or Polydeuces (/ˌpɒlɨˈdjuːsiːz/; Greek: Πολυδεύκης, Poludeukēs, "much sweet wine"[1]) were twin brothers in Greek and Roman mythology and collectively known as the Dioskouroi. They were the sons of Leda by Tyndareus and Zeus respectively, the brothers of Helen of Troy and Clytemnestra, and the half-brothers of Timandra, Phoebe, Heracles, and Philonoe. They are known collectively in Greek as the Dioscuri (/daɪˈɒskjəraɪ/; Latin: Dioscūrī; Greek: Διόσκουροι, Dioskouroi, "sons of Zeus") and in Latin as the Gemini (/ˈdʒɛmɨnaɪ/; "twins") or Castores (/ˈkæstəriːz/). They are sometimes also termed the Tyndaridae or Tyndarids (/tɪnˈdɛrɨdiː/ or /ˈtɪndərɪdz/; Τυνδαρίδαι, Tundaridai), later seen as a reference to their father and stepfather Tyndareus.

In the myth the twins shared the same mother but had different fathers which meant that Pollux was immortal and Castor was mortal. When Castor died, Pollux asked Zeus to let him share his own immortality with his twin to keep them together and they were transformed into the Gemini constellation. The pair were regarded as the patrons of sailors, to whom they appeared as St. Elmo's fire.

Contents |

Origins

Their Vedic parallels in the effulgent brother horsemen Asvin sets them firmly in the Indo-European tradition[2] Their archaic and inexplicable name in Spartan inscriptions Tindaridai or in literature Tyndaridai occasioned an explanatory myth of a Tyndareus (Burkert 1985:212), that in turn occasioned incompatible accounts of their parentage, as that for their sisters Helen and Clytemnestra. The better known story is that Zeus disguised himself as a swan and seduced Leda. Thus Leda's children are frequently said to have hatched from two eggs that she then produced. The Dioscuri can be recognized in vase-paintings by the skull-cap they wear, the pilos, which was already explained in Antiquity as the remnants of the egg from which they hatched.[3] Tyndareus, Leda's mortal husband, is then father or foster-father to the children.[4] Whether the children are thus mortal and which half-immortal is not consistent among accounts, nor is whether the twins hatched together from one egg. In some accounts, only Polydeuces was fathered by Zeus, while Leda and her husband Tyndareus conceived Castor. This explains why they were granted an alternate immortality. It is a common belief that one would live among the gods, while the other was among the dead.

Castor and Polydeuces are sometimes both mortal, sometimes both divine. One consistent point is that if only one of them is immortal, it is Polydeuces. In Homer's Iliad, Helen looks down from the walls of Troy and wonders why she does not see her brothers among the Achaeans. The narrator remarks that they are both already dead and buried back in their homeland of Lacedaemon, thus suggesting that at least in some early traditions, both were mortal. Their death and shared immortality offered by Zeus was material of the lost Cypria in the Epic cycle. They do make an appearance together in the plays by Euripides, Helen and Elektra.

Dioscuri as adventurers

They were both excellent horsemen and hunters who participated in the hunting of the Calydonian Boar and later joined the crew of Jason's ship, the Argo. During the expedition of the Argonauts, Pollux took part in a boxing contest and defeated King Amycus of the Bebryces, a savage mythical people in Bithynia. After returning from the voyage, the Dioskouroi helped Jason and Peleus to destroy the city of Iolcus in revenge for the treachery of its king Pelias.

Castor and Pollux aspired to marry the Leucippides, (the "white horse's daughters") Phoebe and Hilaeira, the daughters of a brother of Leucippus ("white horse").[5]

Although both women were already betrothed to their analogous twin brothers of Thebes, Lynceus and Idas, the sons of Aphareus, the twins carried them both off to Sparta, where Phoebe bore Mnesileos to Pollux and Hilaeira bore Anogon to Castor. This began a feud between the four cousins.

The cousins carried out a cattle-raid in Arcadia together but fell out over the division of the meat. After stealing the herd, but before dividing it, the cousins butchered, quartered, and roasted a calf.[6] As they prepared to eat, Idas, who was gigantic, suggested that the herd be divided into two, instead of four, parts, based on which pair of cousins finished their meal first.[6] Castor and Pollux agreed.[6] Idas quickly ate both his portion and Lynceus' portion.[6] Castor and Pollux had been duped. They allowed their cousins to take the entire herd, but vowed to someday take revenge.[6]

Some time later, Idas and Lynceus visited their uncle's home in Sparta.[6] The uncle was on his way to Crete, so he left Helen in charge of entertaining the guests, which included both sets of cousins, as well as Paris, prince of Troy.[6] Castor and Pollux recognized the opportunity to extract revenge, made an excuse that justified leaving the feast, and set out to steal their cousins' herd.[6] Idas and Lynceus eventually set out for home, leaving Helen alone with Paris, who then kidnapped Helen.[6] Thus, the four cousins indirectly set into motion the events that gave rise to the Trojan War.

Meanwhile, Castor and Pollux had reached their destination. Castor climbed a tree to keep a watch as Pollux began to free the cattle. Far away, Idas and Lynceus approached. Lynceus, named for the lynx because he could see in the dark, spied Castor hiding in the tree.[6] Idas and Lynceus immediately understood what was happening. Idas, furious, ambushed Castor, fatally wounding him with a blow from his spear—but not before Castor called out to warn Pollux.[6] In the ensuing brawl, Pollux killed Lynceus and, as Idas was about to kill Pollux, Zeus, who had been watching from Mt. Olympus, hurled a thunderbolt, killing Idas and saving his son.[6]

Returning to the dying Castor, Pollux was given the choice by Zeus of spending all his time on Mount Olympus or giving half his immortality to his mortal brother. He opted for the latter (so giving half his immortality to Castor), enabling the twins to alternate between Olympus and Hades.[7][8] The brothers became part of the stellar constellation Gemini ("the twins"), becoming the two brightest stars in the group: Castor (Alpha Geminorum) and Pollux (Beta Geminorum).

Dioscuri as saviours

When their sister Helen was abducted by the legendary Greek king Theseus, they invaded his kingdom of Attica to rescue her, abducting Theseus' mother Aethra in revenge and carrying her off to Sparta while setting a rival, Menestheus, on the throne of Athens. Aethra was forced to become Helen's slave but was eventually returned to her home by her grandsons Demophon and Acamas following the fall of Troy.

As emblems of immortality and death that were no longer polar opposites, it is not surprising to hear that the Dioscuri, like Heracles were said to have been initiated at Eleusis.[9]

Dioscuri in the service of Cybele

The image of the twins attending a goddess are widespread[10] and link the Dioscuri with the male societies of initiates under the aegis of the Anatolian Great Goddess[11] and the great gods of Samothrace. The Dioscuri are the inventors of war dances, which characterize the Kuretes.

Classical sources

Ancient Greek authors tell a number of versions of the story of Castor and Pollux. Homer portrays them initially as ordinary mortals, treating them as dead in the Iliad, but in the Odyssey they are treated as alive even though "the corn-bearing earth holds them." The author describes them as "having honour equal to gods," living on alternate days due to the intervention of Zeus. In both the Odyssey and in Hesiod, they are described as the sons of Tyndareus and Leda. In Pindar, Pollux is the son of Zeus while Castor is the son of the mortal Tyndareus. The theme of ambiguous parentage is not unique to Castor and Pollux; similar characterisations appear in the stories of Hercules and Theseus.[12]

Depictions

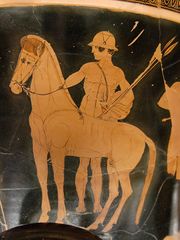

Castor and Pollux are constantly associated with horses in art and literature. They bear striking similarities in this respect to divine twins in other mythologies, especially the Vedic Ashvins, who like them have a close association with horses.[13] Their role as horsemen made them particularly attractive to the Roman equites and cavalry. Each year on July 15, the feast day of the Dioskouroi, the 1,800 equestrians would parade through the streets of Rome in an elaborate spectacle in which each rider wore full military attire and whatever decorations he had earned.[14]

The twins were widely depicted as helmeted horsemen carrying spears.[7] The Pseudo-Oppian manuscript depicts the brothers hunting, both on horseback and on foot.[15] On votive reliefs they are depicted with a variety of symbols representing the concept of twinhood, such as the dokana (δόκανα - two upright piece of wood connected by two cross-beams), a pair of amphorae, a pair of shields, or a pair of snakes. They are also often shown wearing felt caps, above which stars may be depicted. They are depicted on metopes from Delphi showing them on the voyage of the Argo (Ἀργώ) and rustling cattle with Idas. Greek vases regularly show them in the rape of the Leucippides, as Argonauts, in religious ceremonies and at the delivery to Leda of the egg containing Helen.[12] They can be recognized in some vase-paintings by the skull-cap they wear, the pilos (πῖλος), which was already explained in Antiquity as the remnants of the egg from which they hatched.[16]

Worship and interventions

The Dioskouroi were worshipped by the Greeks and Romans alike; there were temples to the twins in Athens and Rome as well as shrines in many other locations in the ancient world.[17]

The Dioscuri and their sisters having grown up in Sparta, in the royal household of Tyndareus, they were particularly important to the Spartans, who associated them with the Spartan tradition of dual kingship and appreciated that two princes of their ruling house were elevated to immortality. Their connection there was very ancient: a uniquely Spartan aniconic representation of the Tyndaridai was as two upright posts joined by a cross-bar;[18] as the protectors of the Spartan army the "beam figure" or dókana was carried in front of the army on campaign.[19] Sparta's unique dual kingship reflects the divine influence of the Dioscuri. When the Spartan army marched to war, one king remained behind at home, accompanied by one of the Twins. "In this way the real political order is secured in the realm of the Gods" (Burkert 1985:212).

Their herōon or grave-shrine was on a mountain top at Therapne across the Eurotas from Sparta, at a shrine known as the Meneláeion where Helen, Melelaus, Castor and Pollux were all said to be buried. Castor himself was also venerated in the region of Kastoria in northern Greece.

They were commemorated both as gods on Olympus worthy of burnt sacrifice, and as deceased mortals in Hades, whose spirits had to be propitiated by libations. Lesser shrines to Castor, Pollux and Helen were also established at a number of other locations around Sparta.[20] The pear tree was regarded by the Spartans as sacred to Castor and Pollux, and images of the twins were hung in its branches.[21] The standard Spartan oath was to swear "by the two gods" (in Doric Greek: νά τώ θεὼ, ná tō theō, in the Dual number).

Roman Castor and Pollux

From the fifth century BC onwards, the brothers were revered by the Romans, probably as the result of cultural transmission via the Greek colonies of Magna Graecia in southern Italy. An archaic Latin inscription of the sixth or fifth century BC found at Lavinium, which reads Castorei Podlouqueique qurois ("To Castor and Pollux, the Dioskouroi"), suggests a direct transmission from the Greeks; the word "qurois" is virtually a transliteration of the Greek word κούροις, while "Podlouquei" is effectively a transliteration of the Greek Πολυδεύκης.[22] The Romans believed that the twins aided them on the battlefield.[23] The construction of the Temple of Castor and Pollux, located in the Roman Forum at the heart of their city, was undertaken to fulfil a vow sworn by Aulus Postumius Albus Regillensis in gratitude at the Roman victory in the Battle of Lake Regillus in 495 BC. According to legend, the twins fought at the head of the Roman army and subsequently brought news of the victory back to Rome.[7] In a very similar vein, the Locrians of Magna Graecia attributed their success at a legendary battle on the banks of the Sagras to the intervention of the Twins. The Roman legend may in fact have had its origins in the Locrian account and possibly supplies further evidence of cultural transmission between Rome and Magna Graecia.[24]

Etruscan, Celtic and Hebrew analogues

The Celts also worshipped Castor and Pollux; the 1st century BC historian Diodorus Siculus records that the twins were the gods most worshipped in the west of Gaul. An altar found at Paris depicts them among Celtic figures such as the god Cernunnos, as well as Roman deities such as Jupiter and Vulcan.[25]

In Celtic mythology, the swan is the escort of the dead into the afterlife, or incarnation of Otherworld, which is very similarly natured to this one. They also feature extensively in the first cycle of Irish Myth featuring the Tuath De Dannan, speficially of Aengus Og, and his lover Etain, who actually become swans. As well as the tale of Mannan Mac Lir, God of the sea, whose children are curse to remain in the form of swans. There my be implications in this idea, regarding the twins, considering that the father of at least one of them is in some cases a god in the guise of a swan- which also lends itself to the roles the twins themselves represent in terms of life death, Olympus and Hades. The idea to Celts that, the twins were children of the swan- (if not biologically to the both, at least adoptively to the other, as Zeus gives Castor god-hood at the love of his brother) could have been very compelling, and in very real terms made statements about the state of human beings regarding life and death for the Celts. The attraction would be intensified with the twin's rendering as horsemen and riders and the Celtic tradition in Gaul and Britain was horse/equestrian bound to an extensively sacred degree. While all or most ancient cultures are bound up with aristocratic horse-borne castes, the majority of Celtic warfare depended on their expression with horse. Equine so saturated their culture, either plentifully or sacredly that horse was a splendid and frequent meal for them. These associations would have made the two twins compellingly 'Celtic' to the Celts. [horse information from Caesar Against the Celts]

In Italy the twins were venerated by the Etruscans, who knew them as Kastur and Pultuce, collectively the tinas cliniiaras ("sons of Tinia [Zeus]"). They were often portrayed on Etruscan mirrors.[26] As was the fashion in Greece, they could also be portrayed symbolically; one example can be seen in the Tomba del Letto Funebre at Tarquinia where a lectisternium for them is painted. They are symbolised in the painting by the presence of two pointed caps crowned with laurel, referring to the Phrygian caps which they were often depicted as wearing.[27]

The Dioskouroi were regarded as helpers of mankind and held to be patrons of travellers and of sailors in particular, who invoked them to seek favourable winds.[28] Their role as horsemen and boxers also led to them being regarded as the patrons of athletes and athletic contests.[29] They characteristically intervened at the moment of crisis, aiding those who honoured or trusted them. Cicero tells the story of how Simonides of Ceos was rebuked by Scopas, his patron, for devoting too much space to praising Castor and Pollux in an ode celebrating Scopas' victory in a chariot-race. Shortly afterwards, Simonides was told that two young men wished to speak to him; after he had left the banqueting room, the roof fell in and crushed Scopas and his guests.[13]

The rite of theoxenia (θεοξενία), "god-entertaining", was particularly associated with Castor and Pollux. The two deities were summoned to a table laid with food, whether at individuals' own homes or in the public hearths or equivalent places controlled by states. They are sometimes shown arriving at a gallop over a food-laden table. Although such "table offerings" were a fairly common feature of Greek cult rituals, they were normally made in the shrines of the gods or heroes concerned. The domestic setting of the theoxenia was a characteristic distinction accorded to the Dioskouroi.[12]

The 'Castor Pollux' notion maybe also lend itself, or vice verse from ancient middle east examples, such as the two men who accompany the Lord to meet and dine with Abraham. They then travel to Sodom to survey the state of the city and its injustices and inhospitalities as to whether or not it should be punished by God. They are met and welcomed by Abraham's nephew Lot. They then are threatened by rape by the town's people and Lot offers his daughters as alternatives. While not specifically named or bearing extensive 'Castor Pollux' traditions, their similarities in 'god entertain' in pairs is striking (see Genesis, chap. 19).

Even after the rise of Christianity, the Dioskouroi continued to be venerated. The fifth-century pope Gelasius I attested to the presence of a "cult of Castores" that the people did not want to abandon. In some instances, the twins appear to have simply been absorbed into a Christian framework; thus fourth-century AD pottery and carvings from North Africa depict the Dioskouroi alongside the Twelve Apostles, the Raising of Lazarus or with Saint Peter. The church took an ambivalent attitude, rejecting the immortality of the Dioskouroi but seeking to replace them with equivalent Christian pairs. Saints Peter and Paul were thus adopted in place of the Dioskouroi as patrons of travellers, and Saints Cosmas and Damian took over their function as healers. Some have also associated Saints Speusippus, Eleusippus, and Melapsippus with the Dioskouroi.[15]

In later culture

Castor et Pollux was the title of a 1737 opera by Jean-Philippe Rameau (libretto by Bernard), modified in 1754. The latter version became quite popular.

In 1842 Lord Macaulay wrote a series of poems about Ancient Rome (the Lays of Ancient Rome). The second poem is about the Battle of Lake Regillus and describes the intervention of Castor and Pollux. They are referred to as the Great Twin Brethren in the poem. [1]

There are at least four sets of twin summits named after Castor and Pollux. In Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming, USA, the peaks are found close to the headwaters of the Lamar River in the Absaroka Range. Another pair is located in the Pennine Alps at the Swiss-Italian border. A third is in Glacier National Park of western Canada, within the Selkirk mountains. The fourth is in Mount Aspiring National Park of New Zealand, named by the explorer Charlie Douglas.

Also the names Castor and Pollux were used for the characters that actors Nicolas Cage and Alessandro Nivola played in the 1997 John Woo film Face/Off. Cage plays terrorist Castor Troy and Nivola plays his brother Pollux.

They were also mentioned in the 1990's t.v show "The Flash", briefly in episode 18 titled "twin streaks"

In the book "Mockingjay" by Suzanne Collins, the protagonist, Katniss Everdeen, receives help from two former Capitol citizens (now are in charge of videotaping everything) named Castor and Pollux. While Castor dies, Pollux lives on, even if he is unable to speak due to a punishment carried out by the Capitol while they were still in control.

References

- ↑ "Dioscuri." Bloomsbury Dictionary of Myth. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Ltd, 1996.

- ↑ Burkert 1985:212.

- ↑ Scholiast on Lycophron, noted by Karl Kerenyi, 1959. The Heroes of the Greeks p.107 note 584.

- ↑ The familiar theme in Greek mythology of the mixed seed of a mortal and an immortal father is played out in various ways: compare Theseus.

- ↑ Phoebe ("the pure") is a familiar epithet of the moon, Selene; her twin's name Hilaeira ("the serene") is also a lunar attribute, their names "appropriate selectively to the new and the full moon" (Kerenyi 1959:109).

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 Potis Stratikis, Greek Mythology, Vol. B, pp. 20-23 (1987).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "Dioscuri." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008.

- ↑ "Castor and Polydeuces." Who's Who in Classical Mythology, Routledge. London: Routledge, 2002.

- ↑ In the oration of the Athenian peace emissary sent to Sparta in 371, according to Xenophon (Hellenica VI), it was asserted that "these three heroes were the first strangers upon whom this gift was bestowed." (Karl Kerenyi, 1967. Eleusis: Archetypal Image of Mother and Daughter (Princeton: Bollingen), p. 122.

- ↑ Kerenyi 1959 draws attention especially to the rock carvings in the town of Akrai, Sicily (1959:111).

- ↑ Burkert 1985:212, who notes Chapouthier, Fernand , Les Dioscures au service d'une déesse, 1935.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Robert Christopher Towneley Parker "Dioscuri." The Oxford Classical Dictionary. Ed. Simon Hornblower and Anthony Spawforth. Oxford University Press 2003.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Dioscūri". Oxford Dictionary of the Classical World. Ed. John Roberts. Oxford University Press, 2007.

- ↑ Myles McDonnell, Myles Anthony McDonnell, Roman Manliness, p. 187. Cambridge University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-521-82788-4

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Alexander Kazhdan, Alice-Mary Talbot "Dioskouroi". The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Ed. Alexander P. Kazhdan. Oxford University Press 1991.

- ↑ Scholiast on Lycophron, noted by Karl Kerenyi, 1959. The Heroes of the Greeks, p. 107 note 584.

- ↑ "Dioscuri". A Dictionary of the Bible. W. R. F. Browning. Oxford University Press, 1997.

- ↑ Burkert 1985; Kerenyi 1959:107)

- ↑ Nick Sekunda, Nicholas Victor Sekunda, Richard Hook, The Spartan Army, p. 53. Osprey Publishing, 1998. ISBN 1-85532-659-0

- ↑ Sarah B. Pomeroy, Spartan Women, p. 114. Oxford University Press US, 2002. ISBN 0-19-513067-7

- ↑ Guy Davenport, Objects on a Table: Harmonious Disarray in Art and Literature, p. 63. Basic Books, 1999. ISBN 1-58243-035-7

- ↑ Mary Beard, John North, Simon Price, Religions of Rome: Volume 1, A History, p. 21. Cambridge University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-521-45646-0

- ↑ "Dioscuri". A Dictionary of World Mythology. Arthur Cotterell. Oxford University Press, 1997.

- ↑ Theodor Mommsen, The History Of Rome, Book II, p. 191. Kessinger Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1-4191-6625-5

- ↑ "Dioscuri". A Dictionary of Celtic Mythology. James McKillop. Oxford University Press, 1998.

- ↑ Giuliano Bonfante, Larissa Bonfante, The Etruscan Language, p. 204. Manchester University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-7190-5540-7

- ↑ Nancy Thomson De Grummond, Erika Simon, The Religion of the Etruscans, p. 60. University of Texas Press, 2006. ISBN 0-292-70687-1

- ↑ "Dioscuri". A Dictionary of World Mythology. Arthur Cotterell. Oxford University Press, 1997.

- ↑ "Dioscūri". The Concise Oxford Companion to Classical Literature. Ed. M.C. Howatson and Ian Chilvers. Oxford University Press, 1996.

Sources

- Ringleben, Joachim, "An Interpretation of the 10th Nemean Ode", Ars Disputandi. Translated by Douglas Hedley and Russell Manning. Pindar's themes of the unequal brothers and faithfulness and salvation, with the Christian parallels in the dual nature of Christ.

- Burkert, Walter, 1985. Greek Religion (Cambridge: Harvard University Press), pp. 212–13.

- Kerenyi, Karl, 1959. The Heroes of the Greeks (Thames and Hundson), pp 105–112 et passim.

- Pindar, Tenth Nemean Ode.

- Theoi Project: Dioskouroi Excerpts in English of classical sources.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||