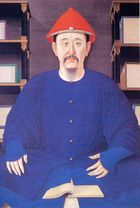

Kangxi Emperor

| Kangxi Emperor | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Reign | 18 February 1661 –

20 December 1722 |

| Predecessor | Shunzhi Emperor |

| Successor | Yongzheng Emperor |

| Regent | Sonin (1661-1667) Ebilong Suksaha (1661-1669) Oboi (1661-1670) |

| Spouse | Empress Xiao Cheng Ren Empress Xiao Zhao Ren Empress Xiao Yi Ren Empress Xiao Gong Ren |

| Issue | |

| Yinti, Beizi Yinreng, Prince Li Mi Yinzhi, Prince Cheng Yinzhen, Yongzheng Emperor Yinqi, Prince Heng Yinzuo Yinyou, Prince Chun Yinsi, Prince Lian Yintang, Beizi Yin'e, State Duke Yinzi Yintao, Prince Fu Yinxiang, Prince Yi Yinti, Prince Xun Yinyu, Prince Yu Yinlu, Prince Zhuang Yinli, Prince Guo Yinwei, Prince Yu Yinxi, Prince Shen Yinhu, Beile Yinqi, Beile Yinmi, Prince Jian |

|

| Full name | |

| Chinese: Àixīn-Juéluó Xuányè 愛新覺羅玄燁 Manchu: Aisin-Gioro Hiowan Yei |

|

| Posthumous name | |

| Emperor Hétiān Hóngyùn Wénwǔ Ruìzhé Gōngjiǎn Kuānyù Xiàojìng Chéngxìn Zhōnghé Gōngdé Dàchéng Rén 合天弘運文武睿哲恭儉寬裕孝敬誠信中和功德大成仁皇帝[Listen] |

|

| Temple name | |

| Qing Shengzu 清聖祖 |

|

| Father | Shunzhi Emperor |

| Mother | Empress Xiao Kang Zhang |

| Born | 4 May 1654 Beijing, Qing Empire |

| Died | 20 December 1722 (aged 68) Beijing, Qing Empire |

| Burial | Eastern Qing Tombs, Zunhua |

The Kangxi Emperor (Chinese: 康熙帝; pinyin: Kāngxīdì; Wade–Giles: K'ang-hsi-ti; temple name: 清聖祖; Mongolian: Энх-Амгалан хаан, 4 May 1654 – 20 December 1722) was the third emperor of the Manchu-led Qing Dynasty[1][2] and the second Qing emperor to rule over China proper, from 1661 to 1722.

His reign of 61 years makes him the longest-reigning Chinese emperor in history (although his grandson Qianlong had the longest period of de facto power) and one of the longest-reigning rulers in the world. However, having ascended the throne aged seven, he was not the effective ruler until later, that role being fulfilled by his four guardians and his grandmother, the Grand Empress Dowager Xiaozhuang.

The Kangxi Emperor is considered one of China's greatest emperors. He defeated the revolt of the Three Feudatories, forced the Zheng Jing government on Taiwan to submit to Qing rule, blocked Tzarist Russia on the Amur River and expanded the empire in the northwest. He also accomplished such literary feats as the compilation of the Kangxi Dictionary.

Kangxi's reign brought about long-term stability and relative wealth after years of war and chaos. He initiated the period known as the "Prosperous Era of Kangxi and Qianlong" which lasted for generations after his own lifetime. By the end of his reign, the Qing empire controlled all of China proper, Manchuria (including Outer Manchuria), part of Russian Far East, both Inner and Outer Mongolia, and Korea as a protectorate.

Contents |

Early reign

Born on 4 May 1654 to Shunzhi Emperor and Empress Xiao Kang, a Han Chinese, Kangxi was originally given the personal name Xuanye (Chinese: 玄燁). He succeeded the imperial throne at the age of seven, on 7 February 1661, twelve days after his father's death, although the Kangxi reign formally began on 18 February 1662, the first day of the following lunar year.

According to some accounts, his father, Emperor Shunzi, gave up the throne to Kangxi and became a monk. Several alternative explanations are given for this: one is that it was due to the death of his favourite consort; another is that he was under the influence of a Buddhist monk. The story goes that the empress dowager ordered a cover-up in which the fact of Shunzi becoming a monk was deleted from the official history and replaced with the claim that he died from smallpox, and indeed this is what many historians still believe. Certainly the court archive has been discovered to show that during the reign of Shunzi, smallpox was the biggest killer in China.

Kangxi was not able to rule in his minority; the Shunzhi Emperor had appointed Sonin, Suksaha, Ebilun, and Oboi as the regents. Sonin died soon after his granddaughter became Empress Heseri, leaving Suksaha at odds with Oboi politically. In a fierce power struggle, Oboi had Suksaha put to death and seized absolute power as sole regent. Kangxi and the court acquiesced in this arrangement.

In 1669 the emperor arrested Oboi with the help of Grand Dowager Empress Xiaozhuang and began to take control of the country himself. He listed three issues of concern: flood control of the Yellow River, repairing the Grand Canal and the Revolt of the Three Feudatories in South China.

Wars

Southern Mainland China and Taiwan

In the spring of 1662 the regents had ordered the Great Clearance in southern China in order to fight a movement begun by Ming Dynasty loyalists under the leadership of Zheng Chenggong (also known as Koxinga) to regain Beijing. This involved moving the entire population of the coastal regions of southern China inland.

The Revolt of the Three Feudatories broke out in 1673 and presented a major challenge. Wu Sangui's forces had overrun most of southern China and he tried to ally himself with local generals such as Wang Fuchen. Kangxi, however, united his court in support of the war effort and employed capable generals such as Zhou Pei Gong and Tu Hai to crush the rebellion. He also extended clemency to the common people who had been caught up in the fighting. Although Kangxi personally wanted to lead the battles against the Three Feudatories, he was advised not to by his advisors. (Kangxi would later lead the fight against the Mongol Dzungars.)

After the surrender of the Zheng family, the Qing Dynasty annexed Taiwan in 1684. Soon afterwards, the coastal regions were ordered to be repopulated, and to encourage settlers, the Qing government gave a financial incentive to each settling family.

Vietnam

In a diplomatic success, the Kangxi government helped mediate a truce in the long-running Trịnh–Nguyễn War in the year 1673. The war in Vietnam between these two powerful clans had been going on for 45 years from 1627 to 1672 without result. The peace treaty that was signed lasted for 101 years until 1774.[3]

Russia

A Russian advance from the north made it necessary for the Qing Dynasty to fight the Russian Empire in the Sahaliyan ula (Amur, or Heilongjiang) Valley region in the 1650s, the outcome being a Qing victory.

The Russians invaded the northern frontier again in the 1680s. After a series of battles and negotiations, the two empires signed the Treaty of Nerchinsk in 1689 giving the Manchu Empire the Amur valley and fixing a border.

Mongols

A rebellion led by Burni of the Chahar Mongols started in 1675. Kangxi crushed the rebellious Mongols within two months and incorporated the Chahar into the Eight Banners.

The Khalkha Mongols had preserved their independence and only paid tribute to the Qing Empire. However a conflict between the houses of Jasaghtu Khan and Tösheetü Khan led to a dispute between the Khalkha and the Dzungar Mongols over influence over Tibetan Buddhism. In 1688 Galdan, the Dzungar chief, invaded and occupied the Khalkha homeland. The Khalkha royal families and the first Jebtsundamba Khutughtu crossed the Gobi Desert and sought help from the Qing state in return for submission to Qing authority. In 1690 the Dzungar and the Qing Empire clashed at the battle of Ulaan Butun in Inner Mongolia, during which the Qing army was severely mauled by Galdan.

In 1696, the Kangxi Emperor himself as commander in chief led three armies with a total of 80,000 in a campaign against the Dzungars. The notable second-in-command general behind Kangxi was Fei Yang Gu (費揚古) who was personally recommended by Zhou Pei Gong (周培公). The western section of the Qing army crushed Galdan's army at the Battle of Zuunmod, and Galdan died the next year.

The Dzungars continued to threaten the Qing Empire and invaded Tibet in 1717. In response to the deposition of the Dalai Lama and his replacement with Lha-bzan Khan in 1706, they took Lhasa with a 6,000-strong army and removed Lha-bzan from power. They held the city for two years, destroying a Manchu army in 1718. Lhasa was not retaken until 1720.

Army

The main army of the Qing, the Eight Banner Army, was in decline under Kangxi. It was smaller than it had been at its peak under Huang Taji and in the early reign of Shunzhi; however, it was larger than in the later Yongzheng period and even more so than the Qianlong period. In addition, the Green Standard Army was still powerful with generals such as Tu Hai, Fei Yang Gu, Zhang Yong, Zhou Pei Gong, Shi Lang, Mu Zhan, Shun Shi Ke and Wang Jing Bao. These generals were abler than those of the Qianlong period.

The main reason for this decline was a change in system between Kangxi and Qianlong's reign. During Kangxi's reign, the empire still used the ancestor's military system that was far more efficient and strict. In the old system, if a general was to return from battle by himself he was to be slain, and if a soldier returned by himself he also was to be slain. This was meant to motivate generals and soldiers to fight valliantly because there would be no advantage to surviving.

By Qianlong's reign, the regime's generals had become lax and saw the training of the army as less important than previously. This was because a general's status was hereditary; his ancestors had already given him fame. Also, during Kangxi's reign the need was to reunify China, which meant the generals were kept busy with wars, but by Qianlong's reign this was no longer true.

Treasury

The contents of the national treasury in the Kangxi Emperor's reign was:

- 1668 (7th year of Kangxi): 14,930,000 taels

- 1692: 27,385,631 taels

- 1702-1709: approximately 50,000,000 taels with little variation during this period

- 1710: 45,880,000 taels

- 1718: 44,319,033 taels

- 1720: 39,317,103 taels

- 1721 (60th year of Kangxi, second last of his reign): 32,622,421 taels

Kangxi was not of age when he became emperor, and did not have control of affairs of state until after the arrest of the regent Oboi in 1669.

The reasons for the great decline in the later years were that war had been taking great amounts of money from the treasury, that the border defense against the Dzungars and the later civil war in Tibet had been costly, and that in Kangxi's old age he had less energy to deal with corrupt officials.

To cure this treasury problem, Kangxi gave Prince Yong (the future Emperor Yongzheng) advice on how to make the economy more efficient. The other problem that concerned Kangxi when he died was the civil war in Tibet; both that problem and the treasury problem would be solved during Yongzheng's reign.

Cultural achievements

Kangxi ordered the compilation of the most complete dictionary of Chinese characters ever put together, the Kangxi Dictionary. In many ways this was an attempt to win over the Chinese scholar-gentry. Many of these initially refused to serve the dynasty and remained loyal to the Ming Dynasty. However, by persuading them to work on the dictionary without asking them to formally serve the Qing, Kangxi in effect led them to gradually take on more and more responsibilities until they became normal officials.

The great compilation of Tang Dynasty poetry, the Quantangshi, was also produced, by imperial order, in 1705.

Kangxi also was keen on Western technology and tried to bring it to China. This was helped through Jesuit missionaries such as Ferdinand Verbiest whom he summoned almost every day to the Forbidden City.

From 1711 to 1723 Matteo Ripa, an Italian priest born near Salerno, sent to China by Propaganda Fide, worked as a painter and copper-engraver at the Qing court. In 1723 he returned to Naples from China with four young Chinese Christians, in order to let them become priests and go back to China as missionaries; this began the "Collegio dei Cinesi" sanctioned by Pope Clement XII to help the propagation of Christianity in China. This Chinese Institute was the first school of Sinology in Europe and the nucleus of what would go on to become the Instituto Orientale and today's Università degli studi di Napoli L'Orientale (Naples Eastern University).

Kangxi was also the first Chinese Emperor to play a western instrument, the piano. He also invented a Chinese calendar.

Christianity

In the early decades of Kangxi's reign, Jesuits played a large role in the imperial court. With the knowledge of astronomy they had brought, they ran the imperial observatory. Jean-François Gerbillon and Thomas Pereira served as emissaries to Russia for the emperor, and managed to secure a peace that halted Russian expansionism in the East, with the Treaty of Nerchinsk. The emperor was grateful to the Jesuits for their contributions to his court, the many languages they could interpret, and the innovations they offered his military in gun manufacturing[4] and artillery, the latter of which had enabled the empire to reconquer Taiwan.[5]

The emperor was also fond of the Jesuits' respectful and unobtrusive manner; they spoke Chinese well, and wore the silk robes of the elite.[6] So in 1692, when Fr. Thomas Pereira requested tolerance for Christianity, the Kangxi Emperor was willing to oblige, and issued the Edict of Toleration,[7] which recognized Catholicism, barred attacks on their churches, and legalized their missions and the practice of Christianity by Chinese people.[8]

But the good will did not last. Controversy arose over whether Chinese Christians could still take part in traditional Confucian ceremonies and ancestor worship, with the Jesuits arguing for tolerance and the Dominicans taking a hard-line against foreign "idolatry". The Dominican position won out with Pope Clement XI, who in 1705 sent Charles-Thomas Maillard De Tournon as his representative to the emperor, to communicate the ban on Chinese rites.[4][9] On 19 March 1715, Clement issued the papal bull Ex illa die, which officially condemned Chinese rites.[4]

In response, the Kangxi Emperor officially forbade Christian missions in China, as they were "causing trouble".[10]

Disputed succession

The matter of Kangxi's will is one of the "Four greatest mysteries of the Qing Dynasty". To this day, whom Kangxi chose as his successor is still a topic of debate amongst historians: on the face of things, he chose Yinzhen, the Fourth Imperial Prince, who went on to become Emperor Yongzheng, and indeed there is strong evidence that this is correct. However many have claimed that Yongzheng forged the will, and that in reality Yinti, the Fourteenth Prince, had been chosen as successor.

Kangxi's first empress gave birth to his second surviving son Yinreng, who at the age of two was named Crown Prince of the empire, a Han Chinese custom, to ensure stability during a time of chaos in the south. Although Kangxi left the education of several of his sons to others, he personally brought up Yinreng, intending to fashion him into the perfect heir.

Yinreng was tutored by the mandarin Wang Shan, who was devoted to the prince, and who was to spend the latter years of his life trying to revive Yinreng's position at court. Through the long years of Kangxi's reign, however, factions and rivalries formed. Those who favored the Fourth Prince, Yinzhen, and the Thirteenth Prince, Yinxiang, had managed to keep them in contention for the throne.

Even though Kangxi favoured Yinreng and had always wanted the best for him, Yinreng did not prove co-operative. He was said to have beaten and killed his subordinates, and was alleged to have had sexual relations with one of Kangxi's concubines, which was defined as incest and a capital offence. He also purchased young children from the Jiangsu region for his pleasure. Furthermore, Yinreng's supporters, led by Songgotu, gradually developed a "Crown Prince Party" (太子黨), and this faction wished to elevate Yinreng to the throne as soon as possible, even if it meant using unlawful methods.

Over the years the aging emperor kept constant watch over Yinreng, and was made aware of many of his flaws. The relationship between father and son gradually worsened. Many thought that Yinreng would permanently damage the Qing Empire if he were to succeed the throne. But Kangxi himself also knew that a huge battle at court would ensue if he was to abolish the Crown Prince position entirely. In 1707, forty-six years into his reign, Kangxi decided that after twenty years, he could take no more of Yinreng's actions, which he partly described in the Imperial Edict as "too embarrassing to be spoken of", and decided to demote Yinreng from his position as Crown Prince.

With Yinreng removed and the position empty, discussion began regarding the choice of a new Crown Prince. Yinzhi (胤禔), Kangxi's eldest surviving son, the Da-a-go (大阿哥), was placed to watch over Yinreng in his new-found house arrest, and assumed that because his father placed this trust in himself, he would soon be made heir.

The First Prince had many times attempted to sabotage Yinreng, even employed witchcraft. He went as far as to ask Kangxi for permission to execute Yinreng, but this enraged Kangxi and effectively erased all his chances of succession, as well as his current titles. In court, the Eighth Prince, Yinsi, seemed to have the most support among officials, as well as the Imperial Family.

In diplomatic language, Kangxi advised the officials and nobles at court to stop debating the position of Crown Prince. But despite these attempts to quiet rumours and speculation as to who the new Crown Prince might be, the court's daily business was greatly disrupted. Furthermore, the First Prince's actions led Kangxi to think that it may have been external forces that caused Yinreng's disgrace. In the third month of the 48th year of Kangxi's reign (1709), with the support of the Fourth and Thirteenth Princes, Kangxi re-established Yinreng as Crown Prince to avoid further debate, rumours and disruption at the imperial court. Kangxi explained Yinreng's former wrongs to be a result of mental illness, and that now he had had time to recover he was thinking reasonably again.

In 1712, during Kangxi's last visit south to the Yangtze region, Yinreng and his faction yet again vied for supreme power. Yinreng ruled as regent during daily court business in Beijing. He decided to allow an attempt at forcing Kangxi to abdicate when the emperor returned to Beijing. Through several credible sources, Kangxi received the news and, with power in hand, saved the empire from a coup d'etat. When he returned to Beijing in December 1712, he was enraged, and removed the Crown Prince once more. Yinreng was sent to court to be tried and placed under house arrest.

Kangxi had made it clear that he would not grant the position of Crown Prince to any of his sons for the remainder of his reign, and that he would place his Imperial Valedictory Will inside a box inside Qianqing Palace, only to be opened after his death. What was in his will is subject to intense historical debate.

Following this, Kangxi made sweeping changes in the political landscape. The Thirteenth Prince, Yinxiang, was placed under house arrest for cooperating with the former Crown Prince. Yinsi, too, was stripped of all imperial titles, only to have them restored years later. The Fourteenth Prince Yinti, whom many considered to have the best chance in succession, was named "Border Pacification General-in-chief quelling rebels" and was away from Beijing when the political debates raged on. Yinsi, along with the Ninth and Tenth Princes, had all pledged their support for Yinti. Yinzhen was not widely believed to be a formidable competitor.

Official documents recorded that during the evening hours of 20 December 1722, Kangxi assembled at his bedside seven of the imperial princes who had not disgraced themselves. These were his third, fourth, eighth, ninth, tenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth sons. After his death, Longkodo announced that Kangxi had selected as his heir the Fourth Prince, Yinzhen. Yinti was in Xinjiang fighting a war when he received word that he had been summoned to Beijing. He did not arrive until days after Kangxi's death. In the meantime Yinzhen had declared that Kangxi had named him as heir and taken the era name Yongzheng. The dispute over his succession revolves around whether Kangxi intended his fourth or fourteenth son to succeed to the throne. (See: Yongzheng)

The Kangxi Emperor was entombed at the Eastern Tombs (東陵) in Zunhua County (遵化縣), Hebei.

Personality and achievements

Kangxi was the great consolidator of the Qing dynasty. The transition from the Ming dynasty to the Qing was a cataclysm whose central event was capture of the capital Beijing by the invading Manchus in 1644, and the installation of their five-year-old ruler as the Shunzhi Emperor. By 1661, when Shunzhi died and was succeeded by Kangxi, the Manchu conquest was almost complete and the leading Manchus were already adopting Chinese ways including Confucian ideology. Kangxi completed the conquest, suppressed all significant military threats and revived the ancient central government system with important modifications.

He was an inveterate workaholic, rising early and retiring late, reading and responding to numerous memorials every day, conferring with his councillors and giving audiences – and this was in normal times; in wartime, he might be reading memorials from the war-front until after midnight or even, as with the Dzungar conflict, away on campaign in person.[12]

He devised a system of communication that circumvented the mandarinate, who had always had a tendency to usurp the power of the emperor, called the Palace Memorial System, involving secret dispatches to and from trusted officials in the provinces, in locked boxes for which only he and the sender had keys. This started as a system for receiving uncensored extreme-weather reports, which the emperor regarded as divine comments on his rule. But it soon evolved into a general-purpose secret 'news channel'. Out of this emerged a committee to deal with out-of-the-ordinary, especially military, events called (in English) the Grand Council, or in Chinese chün-chi chu (Wade-Giles form) which was chaired by the emperor and manned by his more elevated pao-i (Wade-Giles form) Han-Chinese household staff. From this council, the mandarin civil servants were excluded – they were left only with routine administration.[13]

He managed to seduce the Confucian intelligentsia into co-operating with the Qing government, despite their deep reservations about Manchu rule, by encouraging them to sit the traditional civil service examinations, become mandarins and subsequently to compose lavishly-conceived works of literature such as a history of the Ming dynasty, a dictionary, a phrase-dictionary, a vast encyclopedia and an even vaster compilation of Chinese literature. He was himself a cultivated man, steeped in Confucian learning.[14]

In the one military campaign in which he actively participated, that against the Dzungar Mongols, Kangxi showed himself an effective commander. According to Finer, Kangxi's own written reflections allow one to experience “how intimate and caring was his communion with the rank-and-file, how discriminating and yet masterful his relationship with his generals”.[15]

As a result of the scaling down of hostilities as peace returned to China after the Manchu conquest, and also as a result of the ensuing rapid increase of population, land cultivation and therefore tax revenues based on agriculture, the Kangxi Emperor was able first to make tax remissions, then (in 1712) to freeze the land tax and corvée altogether, without embarrassing the state treasury.[16]

Family

- Father: Shunzhi Emperor of China (third son).

- Mother: Concubine from the Tongiya clan (1640–1663). Her family was of Jurchen origin but had lived among Chinese for generations. It had Chinese family name Tong (佟) but switched to the Manchu clan name Tongiya. She was made the Ci He Dowager Empress (慈和皇太后) in 1661 when Kangxi became emperor. She is known posthumously as Empress Xiao Kang Zhang (Chinese: 孝康章皇后; Manchu: Hiyoošungga Nesuken Eldembuhe Hūwanghu).

Consorts

The total number is approximately 64.

- Empress Xiao Cheng Ren (died 1674) from the Heseri clan – married in 1665, Empress Xiaozhuang used this marriage to rule Oboi by Soni.

- Empress Xiao Zhao Ren (Manchu: Hiyoošungga Genggiyen Gosin Hūwanghu) from the Niuhuru clan.

- Empress Xiao Yi Ren (Manchu: Hiyoošungga Fujurangga Gosin Hūwanghu) from the Tunggiya clan, Yongzheng Emperor's foster-mother.

- Empress Xiao Gong Ren (Manchu: Hiyoošungga Gungnecuke Gosin Hūwanghu) from the Uya clan, Yongzheng Emperor's mother.

- Imperial Noble Consort Yi Hui (1668–1743) from the Tunggiya clan, Empress Xiao Yi Ren's younger sister.

- Imperial Noble Consort Dun Chi (1683–1768) from the Guargiya clan.

- Honored Imperial Noble Consort Jing Min (?–1699) from the Janggiya clan.

- Noble Consort Wen Xi (?–1695) from the Niuhuru clan, Empress Xiao Zhao Ren's younger sister.

- Consort Rong (?–1727) from the Magiya clan.

- Consort I (?–1733) from the Gorolo clan.

- Consort Hui (?–1732) from the Nala clan.

- Consort Shun Yi Mi (1668–1744) from the Wang clan was Han Chinese from origin.

- Consort Chun Yu Qin (?–1754) from the Chen clan.

- Consort Liang (?–1711) from the Wei clan.

- Consort Cheng (?–1740) from the Daigiya clan.

- Consort Xuan (?–1736) from the Borjigit clan was Mongol by origin.

- Consort Ding (1661–1757) from the Wanliuha clan.

- Consort Ping (?–1696) from the heseri clan, Empress Xiao Cheng Ren's younger sister.

- Consort Hui (different Chinese character from Consort 'Hui')(?–1670) from the Borjigit clan.

Sons

Having the longest reign in Chinese history, Kangxi also has the most children of all Qing Dynasty emperors. He had officially 24 sons and 12 daughters. The actual number is higher, as most of his children died from illness.

| #1 | Record Name2 | 谱名 | Mother | Title | 爵位 | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chenghu | 承祜 | Imperial Consort Hui | died young | ||||

| Chengrui | 承瑞 | Empress Xiao Cheng Ren | 1669–1672 | died young | |||

| Chengqing | 承慶 | died young | |||||

| Sayinchamhg | 賽音察渾 | Imperial Consort Rong | died young | ||||

| Changhua | 長華 | Imperial Consort Rong | died young | ||||

| Changsheng | 長生 | Imperial Consort Rong | died young | ||||

| 1 | Yinshi | 胤禔 | Imperial Consort Hui | 1672–1734 | Beizi | Born Baoqing | |

| 2 | Yinreng | 胤礽 | Empress Xiao Cheng Ren | 1674–1725 | Crown Prince | 太子 | Crown Prince title abolished in 1708 and 1712 |

| Wanpu | 萬黼 | 1674–1679 | died at 5 years old | ||||

| Yinzhan | 胤禶 | 1675– | died young | ||||

| 3 | Yinzhi | 胤祉 | Imperial Consort Rong | 1677–1732 | Prince Cheng | 诚亲王 | peerage revoked by Yongzheng |

| 4 | Yinzhen | 胤禛 | Empress Xiao Gong Ren | 1678–1735 | Prince Yong | 雍亲王 | Emperor 1722-1735 |

| 5 | Yinqi | 胤祺 | Imperial Consort Yi | 1679–1732 | Prince Heng | 恒亲王 | |

| 6 | Yinzuo | 胤祚 | Empress Xiao Gong Ren | 1680–1685 | Died young | ||

| 7 | Yinyou | 胤祐 | Imperial Consort Cheng | 1680–1730 | Prince Chun | 淳君王 | |

| 8 | Yinsi | 胤禩 | Imperial Consort Liang | 1681–1726 | Prince Lian | 廉亲王 | Title abolished, expelled from clan, Renamed Akina (阿其那) |

| 9 | Yintang | 胤禟 | Imperial Consort Yi | 1683–1726 | Beizi | 贝子 | Titles removed, expelled from clan, Renamed Seshe (塞思黑) |

| 10 | Yin'e | 胤䄉 | Noble Consort Wen-Xi | 1683–1731 | State Duke | 辅国公 | Titles removed |

| 11 | Yinzi | 胤禌 | Imperial Consort Yi | 1684 | Died young | ||

| 12 | Yintao | 胤祹 | Imperial Consort Ding | 1685–1764 | Prince Fu | 履亲王 | Given peerage by nephew Qianlong Emperor |

| 13 | Yinxiang | 胤祥 | Imperial Noble Consort Jing-Min | 1686–1730 | Prince Yi | 怡亲王 | Peerage title inherited |

| 14 | Yinti | 胤禵 | Empress Xiao Gong Ren | 1688–1756 | Prince Xun | 恂郡王 | Peerage title abolished, rumored to be Kangxi's actual successor Born Yinzheng (胤祯), to avoid the nominal taboo of the Emperor, change into Yunti(允禵) |

| 15 | Yinyu | 胤禑 | Imperial Consort Shu-Mi-Yi | 1693–1731 | Prince Yu | 愉郡王 | |

| 16 | Yinlu | 胤祿 | Imperial Consort Shu-Mi-Yi | 1695–1768 | Prince Zhuang | 莊亲王 | Adopted by another branch of clan |

| 17 | Yinli | 胤礼 | Imperial Consort Jin | 1697–1738 | Prince Guo | 果亲王 | |

| 18 | Yinxie | 胤祄 | Imperial Consort Shu-Mi-Yi | 1701–1708 | Died young | ||

| 19 | Yinji | 胤禝 | Imperial Concubine Xiang | 1706–1708 | Died young | ||

| 20 | Yinwei | 胤禕 | Imperial Concubine Xiang | 1693–1731 | Prince Yu | 愉郡王 | |

| 21 | Yinxi | 胤禧 | Imperial Concubine Xiang | 1711–1758 | Prince Shen | 慎郡王 | |

| 22 | Yinhu | 胤祜 | Imperial Concubine Jin | 1711–1731 | Beile | 贝勒 | |

| 23 | Yinqi | 胤祁 | Imperial Concubine Jing | 1713–1731 | Beile | 贝勒 | |

| 24 | Yinmi | 胤祕 | Imperial Concubine Mu | 1716–1773 | Prince Jian | 缄亲王 |

- Notes: (1) The order by which the princes were referred to and recorded on official documents were dictated by the number they were assigned by the order of birth. This order was unofficial until 1677, when Kangxi decreed that all of his male descendants must adhere to a generation code as their middle character (see Chinese name). As a result of the new system, the former order was abolished, with Yinzhi becoming the First Prince, thus the current numerical order. (2) All of Kangxi's sons changed their names upon Yongzheng's accession in 1722 by modifying the first character from "胤" (yin) to "允" (yun) to avoid the nominal taboo of the emperor. Yinxiang was posthumously allowed to change his name back to Yinxiang. Yongzheng forced his two brothers to rename themselves, but his successor recovered their names. There have been many studies on their meanings.[17][18]

Daughters

- Third daughter: Princess Rong Xian (固倫榮憲公主)

- Fifth daughter: Princess Duan Jing (和碩端靜公主)

- Sixth daughter: Princess Ke Jing

- Seventh daughter: Princess (1682–1682), daughter of Empress Xiao Yi Ren

- Eighth daughter: Princess Wen Xian (固倫溫憲公主) (1683–1702)

- Tenth daughter: Princess Chun Que

- Twelfth daughter: 1686–1697

- Thirteenth daughter: Princess Wen Ke

- Fourteenth daughter: Princess Que Jing

- Fifteenth daughter: Princess Dun Ke

In fiction and popular culture

Books

- Kangxi is featured in Louis Cha's Wuxia novel The Deer and the Cauldron. He had a close relationship with the protagonist Wei Xiaobao, who helped him consolidate power and strengthen his rule over the empire.

- A 2001 novel entitled The Great Kangxi Emperor (康熙王朝) by novelist Er Yuehe featured a romanticised version of the emperor's biography.

Film and television

- A Chinese CCTV 46-episode drama series titled Kangxi Dynasty (康熙王朝), based on the novel of the same title by Er Yuehe, was broadcast in 2001, starring Chen Daoming as the Kangxi Emperor.

- Kangxi was also featured as the leader of the Chinese people in the real-time strategy game Age of Empires III: The Asian Dynasties.

See also

- Kangxi dictionary

- Oboi

- Ming Zhu

Notes

- ↑ Schirokauer, Conrad (2006). A Brief History of Chinese Civilization, Thompson Wadswoth, pp. 234-235

- ↑ He can be viewed as the fourth emperor of the dynasty, depending on whether the dynasty's founder, Nurhaci, who used the title of Khan but was posthumously given imperial title, is to be treated as an emperor or not

- ↑ SarDesai, D. R. (1988). Vietnam, Trials and Tribulations of a Nation, p. 38

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Mantienne, p. 180

- ↑ 'Les Missions Etrangeres, p. 83

- ↑ Manteigne, p. 178

- ↑ "In the Light and Shadow of an Emperor: Tomás Pereira, S.J. (1645-1708), the Kangxi Emperor and the Jesuit Mission in China", An International Symposium in Commemoration of the 3rd Centenary of the death of Tomás Pereira, S.J., Lisbon, Portugal and Macau, China, 2008, http://www.viadeo.com/hub/affichefil/?hubId=0021blweg7pn3crr&forumId=002hj6ldao5cz20&threadId=00226fi31xx53g5d

- ↑ Neill, S. (1964). A History of Christian Missions, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, pp. 189-l90

- ↑ Aldridge, Alfred Owen, Masayuki Akiyama, Yiu-Nam Leung. Crosscurrents in the Literatures of Asia and the West, p. 54 [1]

- ↑ Li, Dan J., trans. (1969). China in Transition, 1517-1911, New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, p. 22

- ↑ 明孝陵两大“碑石之谜”被破解 (Solving the two great riddles of the Ming Xiaoling's stone tablets). People's Daily, 13 June 2003. Quote regarding the Kangxi's stele text and its meaning: "清朝皇帝躬祀明朝皇帝 ... 御书“治隆唐宋”(意思是赞扬朱元璋的功绩超过了唐太宗李世民、宋高祖赵匡胤)"

- ↑ Finer (1997), pp. 1134-5

- ↑ Finer (1997), pp. 1135-40

- ↑ Finer (1997), pp. 1140-1

- ↑ Finer (1997), p. 1142

- ↑ Finer (1997), pp. 1156-7

- ↑ 章曉文、陳捷先 (2001). 雍正寫真. 遠流出版公司

- ↑ 史松 (2009). 雍正研究/满族清代历史文化研究文库. 辽宁民族出版社

References

- Finer, S. E. (1997). The History of Government from the Earliest Times. ISBN 0-19-822904-6 (three-volume set, hardback)

External links

Sources

- Spence, Jonathan (1974). Emperor of China: Self-Portrait of K'ang-hsi, Jonathan Cape. ISBN 0224009400

|

Kangxi Emperor

House of Aisin-Gioro

Born: 4 May 1654 Died: 20 December 1722 |

||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by The Shunzhi Emperor |

Emperor of China 1661–1722 |

Succeeded by The Yongzheng Emperor |